Abstract

Recently, the relationship between green human resource management (GHRM) and environmental performance has received a lot of attention from scholars. Teaching, training, and research and development carried out in higher education institutions, which are crucial sources for the promotion of sustainability, encourage GHRM. Using signaling theory, this study aimed to deal with the different roles of green training in the Ministry of Education’s corporate environmental performance. The mediation analysis of organizational citizenship behavior towards the environment was considered and the moderation role of perceived organizational support was evaluated. A survey was prepared to analyze the opinions of managers and staff of the Ministry of Education in Iran. After collecting the surveys, 211 complete responses were analyzed and the most important results from these surveys concluded that: (1) the important tools in adopted strategies for green training improve organizational citizenship behavior towards the environment (OCB) and the Ministry of Educations’ environmental performance; (2) the role of OCB in mediating the effects of training on corporate environmental performance (CEP) is essential; (3) perceived organization support (POS) has a moderation role between green training and CEP.

1. Introduction

Today, some global concerns are caused regarding the protection and sustainability of the environment, which has led to the implementation of responsible management for the environment within organizations [1,2]. This is due to the high importance of environmental responsibilities in organizations operating in a competitive global economy and the necessity of maintaining high efficiency [3]. Responding to external developments can increase the demand for an organization’s goods or services by customers and strengthen its competitive position [4]. Therefore, organizations must strategically implement environmental management. To address environmental concerns, various approaches have been developed, including technological perspectives and “green” human resource management (GHRM) [5]. GHRM is an attractive and emerging research field that plays an important role in achieving an organization’s environmental goals [6,7]. GHRM can ensure an optimal relationship between organizations and relevant stakeholders [8]. It should be mentioned that most of the studies conducted regarding the GHRM approach focus on the knowledge of the effects of its application at the organizational or individual level. GHRM can be an example of practices used to identify employee behaviors in the first stream [9,10]. The second stream deals with the effects of “green” human resource management on corporate environmental performance (CEP) [11,12].

Green education provides green knowledge, develops attitudes and behavioral patterns that introduce sustainable ways of developing and conducting business, maintains a network of green education practitioners who share knowledge and experiences regarding green education, and fosters changes in values regarding environmental sustainability. To achieve environmental performance, firms must use GHRM strategies. People are more inclined to identify with businesses that use green business methods, therefore businesses can profit from embracing GHRM practices. The crucial role of GHRM and POS was conducted by ref. [13] in hotels, but there is no quantitative study concerning the Ministry of Education. Several studies have assessed the individual effects of GHRM practices (such as green training and rewarding) and perceived green organizational support on employees’ outcomes related to green work [14,15] or the influence of top management commitment and corporate social responsibility on these GHRM practices. The mentioned studies offer proof of how human resource practices affect organizational support. Employee perceptions of green organizational support are greatly influenced by green human resource management. An organization that values its employees’ contributions to environmental sustainability and green management and cares about their well-being would use GHRM strategies for things such as selection, training, and rewards [16]. In the literature, there is still no study that connects GHRM to CEP through the moderation role of POS and the mediating responsibilities of OCB. It should be recognized that the environmental behavior of employees contributes to the improvement of CEP and that this is a concept on which the success of an organization, especially the environmental management department, largely depends. Kim et al. [17] conducted research focusing on investigating the relationship between the green performance of hotel employees and GHRM based on their green behavior. However, there is no study on the moderation analysis of POS or the mediating roles of OCB by considering the contribution of GHRM practices [8,11,16].

One of the significant duties of GHRM practices is to stimulate employees’ green attitudes and behaviors in organizations, which has been noted by various researchers [14,15,16]. In addition, one of the roles of GHRM practices is to promote the environmental effects of organizations [18]. Despite the significant increase in publications in the field of GHRM, very little research has been conducted on GHRM in the education industry. For example, we can refer to the exploration of the interactive effects of GHRM-related practices on the voluntary organizational behavior of employees, as performed by Pham et al. [19]. This article, in the context of the scarce research on GHRM with a focus on training, shares interesting findings, such as highlighting the importance of green training in enhancing employee behavior, which can be a critical technique in the interactive model. This research maintains its originality by providing answers to the following questions:

RQ1.

Are OCB and CEP directly influenced by green training practices?

RQ2.

Is the impact of green training practices on CEP mediated by OCB?

RQ3.

Does POS facilitate interactions between practices for green training to influence CEP?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Notion of GHRM Practices and Significance of the Study

As a result of the increased interest in the environment, the environmental consequences of the operational businesses of organizations are receiving more attention [20,21]. This leads to encouraging organizations to use green practices and to integrate them with organizational strategies. It has become one of the legal duties of organizations to deal with the dangerous consequences of their operations and activities. In fact, it has become a strategic necessity to implement green practices and a way to create competitive advantages for organizations regarding aspects of the existing corporate environment [20]. In this regard, researchers have suggested that GHRM should contribute to organizations that can be adopted in achieving their green goals, which occurs with their ability to facilitate the development of positive behaviors and attitudes of employees, considering commercial and social logic [22,23,24]. GHRM can be defined as a process that is necessary to understand the relationship between the evolution, design, implementation, and impact of HRM systems on activities within the organization that affect the environment [6]. Several researchers have discussed the impact of HRM in developing organizations based on sustainability. Jabbour et al. [25] addressed this particular discourse by examining how various elements of environmental management are integrated with human resource practices using primary empirical research methods. They also tried to examine the impact of this integration with human resources in improving environmental performance. Based on the best results of these researchers, the use of human resource management practices, philosophies, and policies to support the prevention of environmental damage as a result of business operations and the sustainable use of resources can be summarized in the concept of GHRM. One of the goals of GHRM is to produce an environmentally aware workforce that is committed to environmental sustainability through the use of appropriate human resource processes [26]. Another case is the use of the green brand by the GHRM department of the organization to attract talents and select qualified candidates based on awareness and environmental knowledge of green criteria [11]. In addition, training employees to improve their awareness of environmental challenges can be put on the agenda. Performance standards can be set based on sustainable and green factors and green goals can be evaluated based on them [27]. In addition to these, the payment and reward system can be linked to the successful realization of environmental goals [8] and support employees to actively participate in creating solutions to environmental problems [6].

The practices that make up GHRM are numerous. To be more precise, setting up green training programs helps the business successfully implement its environmental sustainability operations [28]. These training programs boost employees’ environmental commitment and proactive perceived organizational support by increasing their knowledge of green management and environmental sustainability, adding to their green-related awareness and increasing their knowledge of these topics [14]. These actions combined imply that GHRM is essential to the organization’s ability to achieve its environmental objectives. According to ref. [14], the aforementioned GHRM techniques serve as a foundation for the growth of perceived organizational support for the environment. When HR processes are guided by environmental considerations, certain observations can be made, such as improved efficiency, reduced costs, improved development, and an environment that reinforces the attitude of maintaining sustainable approaches during regular work within organizations. In this regard, Kim et al. [17] conducted a study regarding the evaluation of green and non-green work environments. The study was conducted based on the evaluation of the effect of GHRM on the commitment of employees working in Thailand and its positive effect was also confirmed. In addition, environmental performance and environmentally friendly behaviors were evaluated as above average. Another study, conducted by Shen et al. in China, investigated the effect of GHRM on job performance and employee citizenship behavior [9]. In addition, this study showed the effect of GHRM on the turnover intention with managers’ perceived organizational support and mediating organizational identification. Masri and Jaaron [11] also showed the positive effect of GHRM practices on the environmental performance of manufacturing organizations in Palestine. They were able to identify the least and most impactful practices that may contribute to environmental performance. It is said that in this field, green employment has had the greatest impact. Motivating employees to participate in extra-role and in-role green behaviors through the production of green climate has a positive effect on GHRM practices [20]. Furthermore, they reported that the effect of green values can be moderated using the above relationships. Another study, conducted by Pinzone et al. [16], presented interesting findings regarding the review of National Health System organizations in the UK. They reported that there was a positive relationship between collective behaviors towards the environment by the organization. Similarly, Jabbur et al. [29] showed that in Brazilian manufacturing organizations there is a unique contribution to their environmental management standards using HRM practices.

From the literature related to GHRM, it can be seen that most studies have focused on the impact of GHRM on collective behaviors and environmental performance and all of them have been conducted at the organizational level [11,16]. Those that have been carried out at the employee level have focused on evaluating the impact of GHRM on their behaviors and attitudes toward the environment [9,30]. Therefore, from the above observations, it can be seen that there are gaps in the GHRM research, some of which are:

- Studies on organizational-level outcomes have populated and dominated the GHRM literature and little attention has been paid to employee levels.

- Outcomes from non-green employees have been disregarded, since most of the focus has been on employees at an individual level that is green-oriented.

- The impact of GHRM on the behaviors and attitudes of employees has not been navigated because the focus of the GHRM literature at the employee level has been on existing employee outcomes.

Data from the employment-focused literature suggest that researchers have linked OCB and CEP to GHRM using integrated moderated mediation models. Therefore, according to the literature on human resource management, it is obvious that actions in the field of human resource management did not directly affect the behaviors and attitudes of employees; rather, psychosocial factors are largely responsible for the observed effect [31,32]. Personal attitudinal and emotional perceptions about a potential workplace are referred to as organizational attractiveness. The Ministry of Education would have a higher competitive advantage if it had a better ability to attract applicants, having creative thinking [33], as this would expand the pool of applicants, which inevitably would lead to an increased likelihood of receiving qualified candidates. According to the recruitment literature, the attractiveness of an organization to a candidate initially depends on their perception of the company during the selection process [34]. Using the important principles of signaling and social identity theories, a greater preference for pursuing a career in an organization is based on GHRM organizational practices. It is said that these things make employer organizations more attractive. Based on insufficient information experienced during the job search process, job seekers develop perceptions of employers, as expressed by signaling theory. The signaling theory discusses organizational communication and is outlined as a method for advancing the investigation of HRM procedures. The fundamental responsibilities of the signaler, the signal, and the receiver are what it is primarily focused on (Guest et al., 2021) [32]. According to this idea, organizations (signalers) send a message (signal) to the general public (receiver) through their behavior and business practices and the general public forms opinions about the organizations as a result [32]. This theory postulates that potential employees who do not have enough information about the company are more likely to see any information provided as a positive signal from the work environment, which gives them an idea of how they will be treated during the employment period. If this theory is to be followed, it can be predicted that GHRM will influence the perception of future employees regarding the working conditions by showing the organization’s environmental values and commitments. Organizations that take GHRM seriously and implement it are more likely to be perceived as a positive environment to work in.

Studies conducted by Abrams and Hogg [35] have shown that people’s membership in social groups is closely related to their self-concept. By establishing a relationship with prominent and responsible organizations, these people will see more positive consequences, such as increased self-esteem. GHRM can differentiate an organization from others simply by reflecting its pro-environmental attitudes. This makes working in them seem more desirable compared with competitors. Future employees prefer to associate with these types of organizations to experience higher self-esteem. When they are attracted to a company, they are more likely to convey stronger CEPs and OCBs, as the intention to pursue a career has been reported to be significantly related to a company’s attractiveness [36,37].

Except for Chaudhary’s study [30], there has been no attempt to test the possible relationship between GHRM, OCB, and CEP on prospective employees. Unlike the study done by Chaudhary, this study tries to explain the relationship between potential employee intentions and GHRM using an organization’s credibility as a mechanism; this study takes a different approach. There is a significant difference between prestige and organizational attractiveness. While an organization’s attractiveness is an unclaimed attitude by a potential employee, an organization’s credibility conveys thoughts, reputation, and status [33]. Prestige reflects the consensus of social norms regarding the extent to which a company’s characteristics are perceived, either in a negative or positive perspective, which makes its nature more normative. On the other hand, attractiveness is more of a personal opinion [33].

Bauer and Aiman-Smith [38] suggested that a company’s pro-environmental stance leads to greater attractiveness, higher chances of accepting job offers, and willingness to pursue a career. This study has significant practical and theoretical implications. A particular study on GHRM responds to the critical demand for more research focusing on environmental management and the integration of divergent streams of HRM to achieve environmental sustainability goals [39]. By conducting empirical tests on the link between GHRM, OCB, and CEP, this study provides a basic explanation of the concept of GHRM consequences and its generality. Although this is still in its early stages, it strengthens the development of theory in the field of sustainable human resource management. This study fills an important gap in the literature, particularly where there is insufficient research navigating mechanisms and outcomes linking employees to GHRM. This is conducted by highlighting the psychosocial processes through which GHRM can influence potential applicants’ CEP and OCB.

Similarly, this study investigates the conditions that can stimulate the strength of the relationships discussed above by testing an integrated moderated mediation model. In addition, this study increases the basic understanding and concept of the influence of differences in individuals when shaping the CEP and OCB of future employees. Prospective employees always perceive organizations that engage in GHRM as employers of choice. These findings reveal the potential of turning organizations into talent magnets using GHRM. This information can motivate employers to integrate GHRM with HR practices, policies, and employee initiatives, all of which are conducive to attracting quality applicants. This also means that organizations should emphasize their green practices in recruitment messages and thus make it part of their corporate communications.

Organizations that promote environmental sustainability most often see positive impacts on potential employees during recruitment processes. This is because providing environmental protection information during advertising is effective for building credibility, organizational attractiveness, and willingness to hire [34,38]. Organizations that are not popular for their environmental initiatives are still affected by the implications of this study. When these organizations are looking for a workforce, they are more likely to be overlooked or perceived negatively by prospective employees.

2.2. The Influence of GHRM on OCB

Boieral [40] has described OCB as non-mandatory characters and behaviors that are not recognized and may contribute to an organization’s environmental goals. OCB can be enhanced by focusing on HRM practices that are environmentally oriented in the workplace [7]. As O’Donohue and Torugsa [41] argued, optimizing GHRM policies may facilitate changes in green behaviors. The green abilities necessary to identify environmental problems and take action to reduce their negative effects can be strengthened by providing green training to employees. Hence, spreading environmental values to stimulate green behaviors in employees can be actively promoted by employees who become aware of environmental standards [42]. Green performance management [23] can also stimulate employees’ participation in organizations’ environmental-related activities. The purpose of evaluating the environmental performance of employees is to facilitate a better understanding of tasks and information related to the environment by employees. It also helps improve employees’ willingness to voluntarily participate in green behavior and ensures environmental responsibility in the workplace [16]. Likewise, OCB in activities that promote green events can be considered as an individual element that promotes employees’ ecological behaviors [43]. It can also encourage employees to become involved and generate new ideas for events and activities with environmental issues [11]. In order to encourage OCB at work, Pinzone et al. [16] empirically showed that GHRM practices are important and necessary for this process. Results from a study conducted by ref. [44] stated that the vast majority of participants demonstrated that green performance management and remuneration have a significant impact on organizational citizenship behavior and environmental sustainability.

2.3. The Direct Influence of GHRM on CEP

The positive results of an organization towards its natural environment are called CEP [45]. According to Latan et al. [46], an organization’s green goals, such as environmental performance, can be facilitated by effective strategies for environmental management. Green performance can be greatly improved by an important dimension called GHRM [6]. Employees can be trained in important skills, attitudes, and knowledge related to the environment [29]. This in turn helps employees identify issues related to their environment and address workplace challenges to promote green performance [42]. Likewise, evaluating employees’ environmental performance improves behaviors, ensures employee accountability, and focuses on environmental goals, all of which in turn improve organizations’ green performance [16]. Organizations that focus on OCB usually create opportunities for employees. These opportunities include the use of knowledge and skills by employees in environmental activities, adoption of green initiatives in the workplace [47], providing innovative solutions to reduce waste, efficient use of resources [48], and, as a result, environmental performance. It increases the environment of the organization. A positive correlation between GHRM and environmental performance was illustrated in previous research [49,50,51,52]. Organizations use GHRM to encourage organizational support for an environmental protection attitude, reaffirm the organization’s environmental protection aim, and motivate employees to help achieve the goal through appropriate incentives.

2.4. The Interactive Influence of GHRM on CEP

If these thoughts can be extended to the green landscape, GHRM practices can be expected to experience interactive effects that affect environmental performance. Some of these green practices include training, OCB, and performance management. Employee behavior can be aligned with the organization’s environmental goals through policies that evaluate people’s green performance [47]. Employees can be encouraged to actively participate in pollution prevention [53] and participate in activities that facilitate the generation of new ideas for environmental actions when appropriate opportunities arise [45]. At the same time, the skills and knowledge acquired by an employee through environmental training programs can be essential for pursuing environmental activities and initiatives, correcting mistakes made in work related to environmental issues, and understanding optimal participation in work [54]. As a result of these cases, green opportunities in organizations, the environmental performance of the organization, and the green performance of employees increase. This could also be because employees’ willingness to share and apply environment-related skills and knowledge can be stimulated by green performance management. The result is to increase the green capabilities of employees. At the same time, if senior management provides employees with opportunities to participate in environmental protection activities, a positive atmosphere will be created in the organization. This encourages employees to use the skills and knowledge they have acquired from environmental education activities to gain more knowledge about the requirements of environment-related activities [55,56]. This inevitably increases their green capabilities and subsequently positively affects CEP. Regarding the investigation of the moderating effect of POS, many recent studies have emphasized its role in various fields for creating green organizations and human resource management [57,58,59].

According to the notion of organizational support, different human resource activities trigger employees’ views of organizational support and come from the company’s actions. GHRM strategies would be the company’s way of expressing its commitment to protecting the environment. Research on hotel staff in Palestine found that employing GHRM techniques boosted perceptions of organizational support for the environment [14]. Similarly, investigations in several Pakistani contexts [55] supported the favorable correlation between these factors. The mentioned relationship was also reliable in the oil and gas industry [60]. Evidence from the Italian healthcare sector showed how green training affected pro-environmental behaviors [28]. Green training and organizational support are directly related to organizational behavior toward the environment. Additionally, the level of top management commitment to environmental performance is directly related [60]. Top management commitment is a crucial element in fostering environmental performance and supporting green training toward organizational citizenship behavior. Perceived environmental policies are affected by perceived organizational support [43,61]. Management support is a frequent theme and is seen as a crucial factor in encouraging people to engage in environmental activities at work. The lack of organizational support limits employees’ capacity to engage in environmentally friendly activities, even if it enhances employees’ propensity to do so while at work.

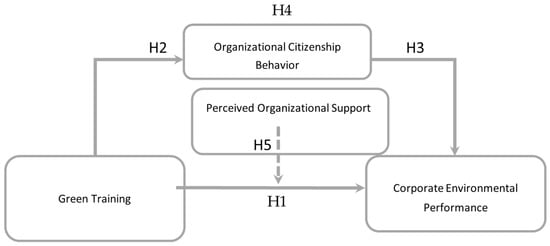

Based on the mentioned literature and approved relationship, this current study’s model is shown in Figure 1. Therefore, this study is going to examine the following hypothesizes:

Figure 1.

The research model.

H1.

There is a direct and positive relationship between green training and CEP.

H2.

There is a direct and positive relationship between green training and OCB.

H3.

There is a direct and positive relationship between OCB and CEP.

H4.

OCB mediates the relationship between green training and CEP.

H5.

POS moderates the relationship between green training and CEP.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

The challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic prompted educational institutions to encourage organizations to develop strategies to create innovation. Applying innovative practices in unpredictable critical periods provides organizations with practical, innovative, and unrivaled technological competitive advantages. When GHRM practices are applied in current situations, they can facilitate OCB and CEP. They can also contribute to sustainability in organizations that primarily rely on non-temporary innovative methods associated with HR practices. However, there is insufficient evidence from previous experience to determine the validity of this relationship. In conclusion, this study examines how OCB and CEP are related in academic institutions and influenced by GHRM practices. This study includes the use of quantitative statistical tools in collecting data from the employees of the Ministry of Education. Their participation in the online survey showed that there is a significant positive relationship between the mentioned factors. Furthermore, they explored the mediating and moderating responsibilities of OCB and POS. The findings of this study showed that the relationship between GHRM and CEP had a significant increase in POS.

For this type of study, two types of sampling plans, including non-probability and probability sampling methods, have been proposed by Saunders et al. [62]. The probabilistic method uses random sampling, where the generalizability of a result to a large population is considered. In contrast, another method of sampling (non-probability) involves a non-random technique and recruits volunteers based on personal perception; it is described as a convenience sampling method and depends on availability. The current research uses the probability sampling method to give each person an equal chance to be selected [63]. Additionally, in order to determine the appropriate sample size, the researchers assume a confidence level of 95%, a standard deviation of 0.5, and a margin of error of ±5%. The margin of error represents the range of reasonable population values for a particular parameter that depends on the difference between the sample size and the data. This can be interpreted to describe the valid range within which the population parameters fall [64]. The headquarters of the ministry was also chosen in Tehran because, based on statistics, compared with other classified departments in Iranian cities, this ministry had a larger organizational structure. The implication was that the ministry was more likely to have special interventions to deal with crises. The information related to the total population and the list of employees of the headquarters was collected through the ministry. Data collection involved the distribution of designed questionnaires through Google and social media channels such as employee WhatsApp groups and employee emails from August 2022; the procedure lasted for three months. The employees were also informed that the information provided by the departments of the ministries was for research purposes only. This allowed the researcher to contact relevant employees based on their current positions and roles (e.g., department heads, department, department managers, employees, etc.) and inform them of the possibility to contact them with further questions. The offices in Tehran and the number of employees were investigated; a total of 300 questionnaires were distributed to the respondents for the target population of this research, which included employees who worked in the Ministry of Education; 211 complete responses were analyzed. To confirm the accuracy of each measurement item, a pilot test of 50 questionnaires was conducted for the current study. The measurement items included green training (GTR), 5 items; OCBE, 3 items; CEP, 6 items; POS, 3 items. It is known that using data from a single source is prone to common method bias. In addition, confidentiality of responses and anonymity of respondents were informed in order to maximize common method bias. The common method bias rate from the collected data was investigated by executing the collinearity test and the variance inflation factors.

3.2. Data Analysis

Upon completion of data gathering, PLS-SEM was performed using SmartPLS 3.X software to test the hypotheses of the research; it was deemed an appropriate application for analyzing such models and has been used in similar studies [64,65]. When an analysis aims to test a theoretical framework from the viewpoint of a prediction, SmartPLS could be undertaken. Assessment of the validity (convergent and discriminant) and the reliability can be conducted directly in SmartPLS. The reliability and validity of the collected data were measured alongside the moderation and mediation effects.

4. Results

Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 exhibit the results of the data analysis. Demographic statistics showed that the majority of respondents were in the age group of 24–35 (56.4%), followed by 36–45 (40.3%), and 46 and above (3.3%). Additionally, female respondents were 111 in total, while male respondents comprised 100 of the total data.

Table 1.

Measurement model.

Table 2.

Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Table 3.

HTMT ratio.

Table 4.

Collinearity statistics.

Table 5.

Significance of the proposed paths.

Table 6.

The mediating effect of OCB.

Table 7.

The moderating effect of POS.

Table 8.

Hypothesis testing.

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

To assess the internal consistency reliability, the evaluation of Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability was conducted. The composite reliability value should be equal to or greater than the satisfactory threshold of 0.7 [66]. Moreover, the threshold for Cronbach’s alpha coefficient would be 0.7 [67]. According to the results illustrated in Table 1, the internal consistency was confirmed, since all the composite reliability values and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were above the necessary threshold. To confirm the convergent validity, average variance extracted (AVE) values needed to be more than 0.5 and outer loading values needed to be greater than 0.708 [64]. Based on the results shown in Table 1, convergent validity was confirmed, as all the AVE and outer loading values were more than the recommended threshold.

To assess the discriminant validity, the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio were evaluated. Discriminant validity was confirmed when each latent variable’s square root of AVE was more than the correlation coefficients amongst other constructs [68]. Furthermore, discriminant validity was confirmed when the HTMT ratio was less than 0.9 [69]. According to the results displayed in Table 2 and Table 3, discriminant validity was confirmed.

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

According to Hair et al. [64], the first step to assess the structural model is to check the multicollinearity issue. To check the multicollinearity issue among the constructs, variance inflation factor (VIF) values need to be checked. VIF values need to be less than the threshold of five. According to the results demonstrated in Table 4, there was no multicollinearity problem, since the VIF values were all less than five. The PLS-SEM results indicated that the model achieved a favorable fit (SRMR = 0.071 < 0.08, NFI = 0.92 > 0.90), based on the acceptance criteria outlined in the works of Hair et al. [64].

In order to assess the significance of the proposed paths, a bootstrapping technique was used. Based on the results shown in Table 5, the paths between green training and OCB, OCEBE and CEP, and Green Training and CEP were all significant, considering a 95% confidence interval. In addition, the R2 value was examined. The value of R2 assesses the explained variance in the dependent variable and indicates the explanatory power of the model [70]. The value of R2 ranges from 0 to 1. High values for R2 show a greater explanatory power. Based on the results of R2, 56.1% of the variance in the dependent variable (CEP) was explained by the independent variable (green training).

4.3. Mediating Effect of OCB

To investigate the indirect effects present in the model, the bootstrapping technique was applied. According to the results displayed in Table 6, green training affected CEP indirectly through OCB. The results show that the indirect effect and the direct effect of green training on OCB were both significant, considering a 95% confidence interval. Thus, OCB partially mediated the relationship between green training and CEP.

4.4. Moderating Effect of POS

This current study hypothesized that POS acted as a moderator in the model and moderated the relationship between green training and CEP. This moderating effect was examined and the result is shown in Table 7. According to the result, the moderating effect of POS was positive and significant, based on a 95% confidence interval, which showed that POS moderated the relationship between green training and CEP.

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

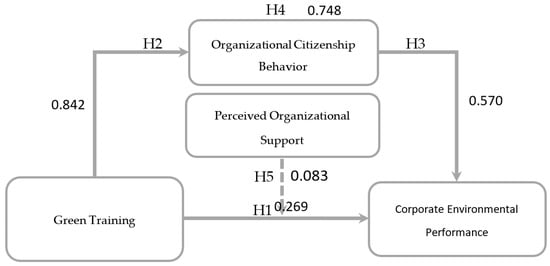

Table 8 illustrates the proposed hypotheses in this current study and, as is seen, all the proposed hypotheses were supported by the results obtained from the conducted analyses in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Coefficients.

5. Conclusions and Implications

This study was conducted to present the fundamental role of green training in the Ministry of Education’s environmental performance and examined a mediation analysis of organizational citizenship behavior and the moderation role of perceived organizational support. The results presented a positive and considerable role of both organizational citizenship behavior and perceived organizational support between green training and the Ministry of Education’s environmental performance. There are several important practical and theoretical contributions to this study. This study navigates the interfering roles of organizational citizenship behavior on how corporate environmental performance is impacted by GHRM practices, signifying the use of the signaling theory. This study goes beyond empirical contributions from similar published papers and approaches the topic from a green context. Unmediated links associating green behavior and performance with green training practices have been focused on by some previous research [11,54]. This study suggests and provides a detailed framework based on a green and sustainable perspective for navigating the relationship between green training and environmental performance by comprehending ways how to identify the mediating responsibilities of behavior and individual green attitudes. This study contributes to the green training literature by pinpointing the claims of the signaling theory in navigating the direct involvement of green training practices and how they contribute to corporate environmental performance. It confirms that the concurrent utilization of green training is a necessary factor for the advancement of human resource management policies linked with the environment. This study contributes to the existing literature and connects the limitations of previous studies that have been published [71].

The findings from this study make theoretical contributions available that emphasize the use of the theory in the investigation of previously mentioned relationships. Additionally, this study assists in filling the gap in research on the Ministry of Education, where there has been insufficient research focused on boosting the comprehension of green training and its relative importance. Therefore, future researchers should focus on gaining a better understanding of methods through which current green practices can be utilized in the Ministry of Education to fine-tune their findings. In conclusion, what was discovered can be practically implied in the Ministry of Education. This study suggests that training on green practices and organizational citizenship behavior are important key practices for environmental management success. Therefore, attention has to be paid to the provision of training programs and opportunities for environmental activities by the Ministry of Education. This would improve the environmental skill, knowledge, and awareness of the individual, alongside developing the green goals of the organization. Moreover, factors that should be required in important departments to improve their environmental responsibilities and attachments include practices that create green motivation in employees. An example would be creating a forum that would focus on protecting the environment, establishing opportunities for employees to engage in green problem-solving groups, or communicating actively with the leaders of the Ministry of Education on environmental matters. A recommendation by interaction analysis is that both organizational citizenship behavior and green training should be simultaneously applied. This suggestion is vital for improving the success of environmental management by twice its capacity, as these training programs could assist employees in understanding how best to effectively provide solutions to environmental problems within the organization. Because of this, the environmental performance of the Ministry of Education would be strengthened. This performance could also geometrically progress if the opportunities developed for the employees would permit them to use their newly developed skills, awareness, and knowledge of environmental matters in their daily activities.

Additionally, one of the critical elements is mediating the relationship between green training and corporate environmental performance that could be perceived by organizational citizenship behavior. Managers would need to use policies focused on encouraging the pro-environmental behaviors of individuals in order to improve the green effectiveness of their ministry of education. They should be disposed to receive suggestions from their employees about strategies for improving and protecting the environment effectively. This would ensure that they are enthusiastic about participating in green activities that would address the environmental problems of the Ministry of Education.

The purpose of “green education” is to empower the people involved to learn and adopt lifelong environmental stewardship habits. It acknowledges that innovative educational strategies foster people’s critical thinking abilities and are the greatest way for them to learn. It requires green culture, a green campus, and green personnel. These GHRM practices have been demonstrated to be the indicators of the practice [72]. Hiring candidates who possess environmental sensitivity, knowledge, and motivation can be carried out using strict selection criteria [29]. Employees who exhibit environmentally friendly or pro-environmental behaviors will be more likely to contribute to the company’s environmental goals and help it meet the requirements of its environmental management program. Employees who are allowed to contribute to decisions concerning environmental sustainability and green management help the company demonstrate its concern for the environment and its commitment to green management. In general, when employees believe that their environmental contributions are respected and appreciated by the organization, they will work diligently and act discretionarily. Employees feel supported at work when the organization values their environmental accomplishments and efforts. Green training, green performance management, green awards, and green recruitment are all relevant to this study. We contend that pro-environmental incentives, pro-environmental performance management, pro-environmental training, and selective recruitment of employees with such awareness are essential for encouraging employee green behaviors. Organizational support and resource commitment moderate the relationship between green knowledge acquisition, green knowledge management, and green technology innovation. This information is useful because it enables managers to concentrate on planning, allocating, and budgeting resources for efficient green practices that can enhance corporate environmental performance. By considering some research focusing on the role of human resource management role in the Ministry of Education or in universities, for example, the crucial role of employees and different managerial levels toward organization and environment cannot be denied. In practice, all will be possible by conducting professional planning and defining related projects [73,74,75,76].

The signaling theory is a theoretical framework that examines the information provided in sustainability reports, taking into account that signaling allows educational centers to shape stakeholders’ opinions, gain a competitive edge, and enhance their performance. Regarding education, advanced degrees from more esteemed universities do not always signify greater ability but they do send a signal to hiring managers that you are important and that they would be smart to hire employees with green, modern, and sustainable behaviors. When two parties (individuals or organizations) have access to various types of training and information, the signaling theory can be used to explain behavior.

6. Limitations and Further Research

Despite the fact that the practical and theoretical implications of the study were acknowledged, this study also had its pitfalls and offered recommendations for future studies. To start with, green training, organizational citizenship behavior, and green performance management were three practices employed in this study. The need for additional green policies such as union roles, green rewards, green organizational culture, and recruitment in future studies could be helpful. Therefore, through future studies, the research could be extended by ensuring the exploration of the impact of these aforementioned practices on corporate green performance. This could be conducted using viable models such as additive, multiplicative, and combinative models. New insights such as the role of green training in the Ministry of Education and its application may be highlighted. Even though this study was designed to ensure generalizability, it would still be interesting to confirm these results in other industries.

Limitations of this study have also been observed and they serve as necessary guidelines for future research. One limitation of the study was the small sample size involved, which questioned its generalizability. Thus, it would be advised that replicating this study should involve a larger population sample from different disciplines. Another limitation would be the use of self-report measures, even though an experimental research design was used. Self-report measures were used to evaluate the variables of the study and they may have exaggerated the strength of the links between the variables. Finally, a variety of moderators such as education, personality, gender, and age could be examined in future studies. This would facilitate the elaboration of the boundary conditions of the link between the outcomes of prospective employees and green training. In addition, conducting a qualitative study using the same variables and concerns would explore new insights into green training and its crucial role in the Ministry of Education. Additionally, different case studies could present different results and attitudes. The authors suggest the effect of staff training at the ministry on the operation of the educational system as a potential research avenue moving forward.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.G.; Investigation, M.G.N.; Writing—original draft, M.A.J.B.; Writing—review & editing, M.G.N.; Supervision, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available according to the request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ouyang, Z.; Wei, W.; Chi, C.G. Environment management in the hotel industry: Does institutional environment matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Singjai, K.; Winata, L.; Kummer, T.-F. Green initiatives and their competitive advantage for the hotel industry in developing countries. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Ramayah, T.; Fawehinmi, O. Nexus between green intellectual capital and green human resource management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Tarí, J.J.; Pereira-Moliner, J.; López-Gamero, M.D.; Pertusa-Ortega, E.M. The effects of quality and environmental management on competitive advantage: A mixed methods study in the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Okumus, F.; Chan, W. What hinders hotels’ adoption of environmental technologies: A quantitative study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 84, 102324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; EJackson, S. GHRM research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 769–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Chen, Y.; Boiral, O.; Jin, J. The Impact of Human Resource Management on Environmental Performance: An Employee-Level Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, Y.M.; Nejati, M.; Kee, D.M.H.; Amran, A. Linking GHRM practices to environmental performance in hotel industry. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Dumont, J.; Deng, X. RETRACTED: Employees’ Perceptions of Green HRM and Non-Green Employee Work Outcomes: The Social Identity and Stakeholder Perspectives. Group Organ. Manag. 2016, 43, 594–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Green human resource practices and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of collective green crafting and environmentally specific servant leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1167–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, H.A.; Jaaron, A.A. Assessing green human resources management practices in Palestinian manufacturing context: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.; Chong, T. GHRM and the enablers of green organisational culture: Enhancing a firm’s environmental performance for sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. GHRM and employee green behavior: An empirical analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Karatepe, O.M. Green human resource management, perceived green organizational support and their effects on hotel employees’ behavioral outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3199–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Phan, Q.P.T. Greening human resource management and employee commitment toward the environment: An interaction model. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 20, 446–465. [Google Scholar]

- Pinzone, M.; Guerci, M.; Lettieri, E.; Redman, T. Progressing in the change journey towards sustainability in healthcare: The role of ‘Green’ HRM. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 122, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M.; Phetvaroon, K. The effect of GHRM on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ghasemi, M.; Nejad, M.G.; Khandan, A.S. Assessing the Potential Growth of Iran’s Hospitals with Regard to the Sustainable Management of Medical Tourism. Health Soc. Care Community 2023, 2023, 8734482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Greening the hospitality industry: How do GHRM practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixed-methods study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Green Human Resource Management: Policies and practices. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2015, 2, 1030817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Berger, S. Sustainability principles: A review and directions. Organ. Manag. J. 2010, 7, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Seo, J. The greening of strategic HRM scholarship. Organ. Manag. J. 2010, 7, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green human resource management: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Yang, X.; Jiang, F.; Yang, Z. How to synergize different institutional logics of firms in cross-border acquisitions: A matching theory perspective. Manag. Int. Rev. 2023, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. The central role of human resource management in the search for sustainable organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 2133–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Feng, Z.; Su, X. Design and Simulation of Human Resource Allocation Model Based on Double-Cycle Neural Network. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 2021, 7149631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Rabiei, S.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Envisioning the invisible: Understanding the synergy between GHRM and green supply chain management in manufacturing firms in Iran in light of the moderating effect of employees’ resistance to change. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzone, M.; Guerci, M.; Lettieri, E.; Huisingh, D. Effects of ‘green’ training on pro-environmental behaviors and job satisfaction: Evidence from the Italian healthcare sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A.; Nagano, M.S. Contributions of HRM throughout the stages of environmental management: Methodological triangulation applied to organizations in Brazil. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1049–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Can GHRM attract young talent? An empirical analysis. In Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Wright, P.M. The Impact of High-Performance Human Resource Practices on Employees’ Attitudes and Behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E.; Sanders, K.; Rodrigues, R.; Oliveira, T. Signalling theory as a framework for analysing human resource management processes and integrating human resource attribution theories: A conceptual analysis and empirical exploration. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2020, 31, 796–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Liu, Q.; Huang, X. The influence of digital educational games on preschool Children’s creative thinking. Comput. Educ. 2022, 189, 104578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrend, T.S.; Baker, B.A.; Thompson, L.F. Effects of pro-environmental recruiting messages: The role of organizational reputation. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Social Identifications: A Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group Processes; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, D.S.; Uggerslev, K.L.; Carroll, S.A.; Piasentin, K.A.; Jones, D.A. Applicant Attraction to Organizations and Job Choice: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Correlates of Recruiting Outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 928–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gully, S.M.; Phillips, J.M.; Castellano, W.G.; Han, K.; Kim, A. A Mediated Moderation Model of Recruiting Socially and Environmentally Responsible Job Applicants. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 935–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N.; Aiman-Smith, L. Green career choices: The influence of ecological stance on recruiting. J. Bus. Psychol. 1996, 10, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Renwick, D.W.S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Muller-Camen, M. State-of-the-Art and Future Directions for Green Human Resource Management: Introduction to the Special Issue. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 25, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Greening the Corporation Through Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 87, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donohue, W.; Torugsa, N. The moderating effect of ‘Green’ HRM on the association between proactive environmental management and financial performance in small firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Salazar, M.D.; Cordón-Pozo, E.; Ferrón-Vilchez, V. Human resource management and developing proac-tive environmental strategies: The influence of environmental training and organizational learning. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 905–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawand, S.; Ghasemi, M.; Sahranavard, S.A. Employee Involvement and Socialization as an Example of Sustainable Marketing Strategy and Organization’s Citizenship Behavior: Empirical Evidence from Beirut Hotel Sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilwan, Y.; Isnaini, D.B.Y.; Pratama, I.; Dirhamsyah, D. Inducing organizational citizenship behavior through GHRM bundle: Drawing implications for environmentally sustainable performance. A case study. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2020, 10, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, B.F.; Bishop, J.W.; Massoud, J.A. The role of training and empowerment in environmental performance: A study of the Mexican maquiladora industry. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2012, 87, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latan, H.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Wamba, S.F.; Shahbaz, M. Effects of environmental strategy, environmental uncertainty and top management’s commitment on corporate environmental performance: The role of environmental management accounting. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Longoni, A.; Luzzini, D. Translating stakeholder pressures into environmental performance–the me-diating role of green HRM practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 262–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R.; Davison, D. Gaining from Green Management: Environmental Management Systems inside and outside the Factory. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 43, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muisyo, P.K.; Qin, S. Enhancing the FIRM’S green performance through green HRM: The moderating role of green innovation culture. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 289, 125720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, M.H.; Abid, M. A study of green HR practices and its impact on environmental performance: A review. Manag. Res. Rep. 2015, 3, 142–154. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, S.; Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, A. How do green knowledge management and green technology innovation impact corporate environmental performance? Understanding the role of green knowledge acquisition. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 32, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Valéau, P.; Carballo-Penela, A. Green rewards for optimizing employee environmental performance: Examining the role of perceived organizational support for the environment and internal environmental orientation. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2022, 20, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindarajulu, N.; Daily, B.F. Motivating employees for environmental improvement. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2004, 104, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, B.B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through GHRMpractices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z.; Naeem, R.M.; Hassan, M.; Naeem, M.; Nazim, M.; Maqbool, A. How GHRM is related to green creativity? A moderated mediation model of green transformational leadership and green perceived organizational support. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 43, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.H.; Saleem, F.; Murtaza, G.; Haq, T.U. Exploring the impact of GHRM on environmental performance: The roles of perceived organizational support and innovative environmental behavior. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 43, 742–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Hsieh, H.; Aboramadan, M. The effects of GHRM and perceived organizational support for the environment on green and non-green hotel employee outcomes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 103, 103202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Pu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Gao, N.; Lu, Y. Role of the e-exhibition industry in the green growth of businesses and recovery. Econ. Chang. Restruct. 2023, 53, 2003–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, H.A.M.; Harun, H.; Noor, A.M.; Hashim, H.M. Green Human Resource Management, Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Citizenship Behavior towards Environment in Malaysian Petroleum Refineries. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 124, 11001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.B.; Rasli, A.; Dahri, A.S.; Hermilinda Abas, I. Importance of Top Management Commitment to Organizational Citizenship Behaviour towards the Environment, Green Training and Environmental Performance in Pakistani Industries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Raineri, N. Linking perceived corporate environmental policies and employees eco-initiatives: The in-fluence of perceived organizational support and psychological contract breach. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2404–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: London, UK, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.M.; Mohammad, A.A.; Kim, W.G. Understanding hotel frontline employees’ emotional intelligence, emotional labor, job stress, coping strategies and burnout. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Using Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in Advertising Research: Basic Concepts and Recent Issues. In Handbook of Research on International Advertising; Elgar, E., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2012; p. 252. ISBN 9781848448582. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, M.; Nejad, M.G.; Alsaadi, N.; Abdel-Jaber, M.; Ab Yajid, M.S.; Habib, M. Performance Measurment and Lead-Time Reduction in EPC Project-Based Organizations: A Mathematical Modeling Approach. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5767356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Misapplications of simulations in structural equation models: Reply to Acito and Anderson. J. Mark. Res. 1984, 21, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Koppius, O.R. Predictive Analytics in Information Systems Research. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Jaaron, A.A.; Bon, A.T. The impact of GHRM and green supply chain management practices on sustainable performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrutha, V.; Geetha, S. A systematic review on green human resource management: Implications for social sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 247, 119131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, B.; Hassanpoor, A.; Navehebrahim, A.; Jafar, S. Designing a Green Human Resource Management Model at University Environments: Case of Universities in Tehran. Evergreen 2020, 7, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Wahshi, A.S. Human resource planning practices in the Omani Public Sector: An exploratory study in the Ministry of Education in the Sultanate of Oman. Ph.D. Thesis, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, WA, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Niyi Anifowose, O.; Ghasemi, M.; Olaleye, B.R. Total Quality Management and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises’(SMEs) Performance: Mediating Role of Innovation Speed. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibeanu, C.; Nejad, M.G.; Ghasemi, M. Developing Effective Project Management Strategy for Urban Flood Disaster Prevention Project in EDO State Capital, Nigeria. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).