Analysis of China–Angola Agricultural Cooperation and Strategies Based on SWOT Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on China’s Agricultural Investment in Africa

2.2. Research on SWOT Analysis

3. Analysis of Agricultural Development Prospects in Angola

3.1. Analysis of Agricultural Development Conditions in Angola

3.2. Analysis of Crop Production in Angola

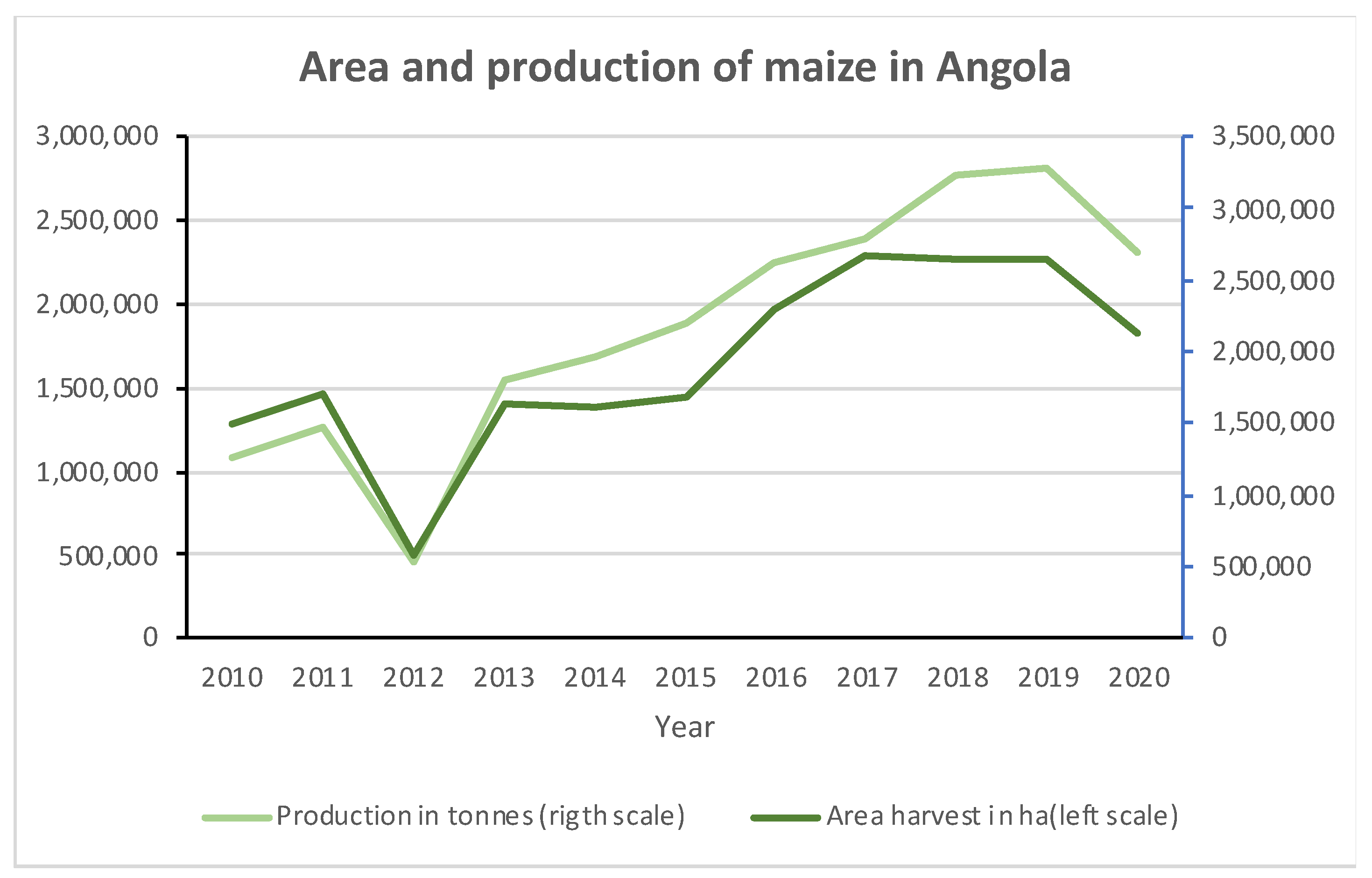

- (1)

- Maize

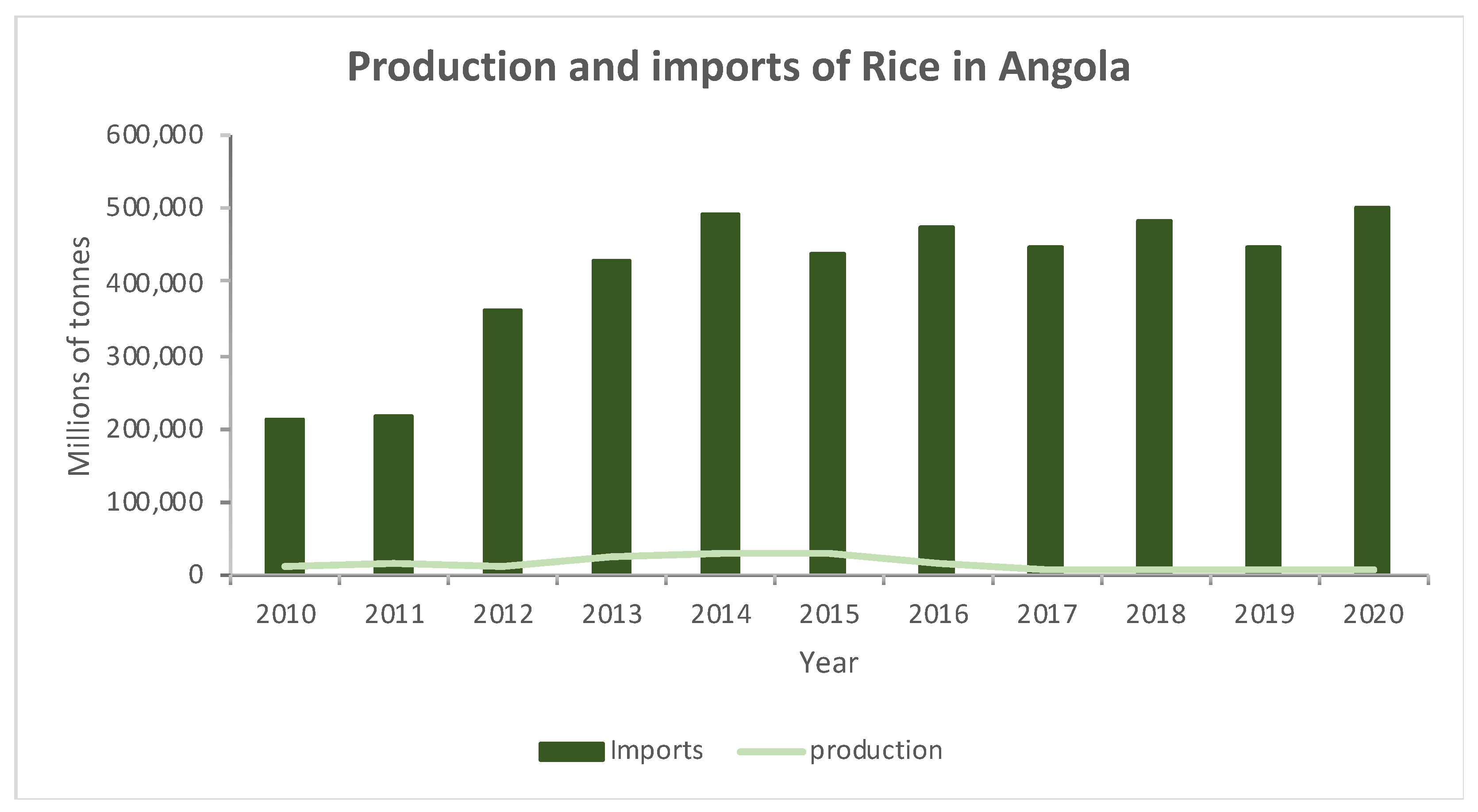

- (2)

- Rice

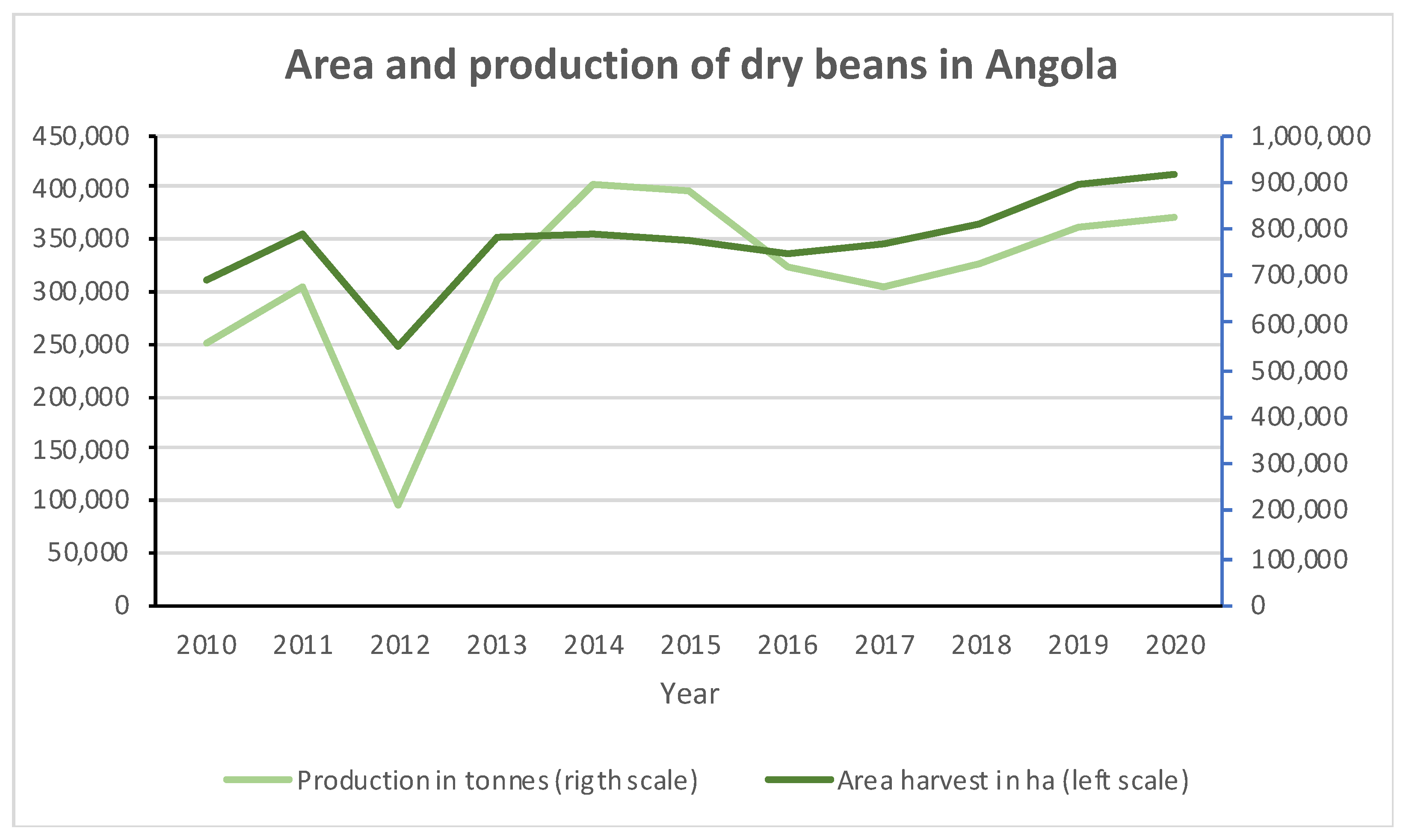

- (3)

- beans

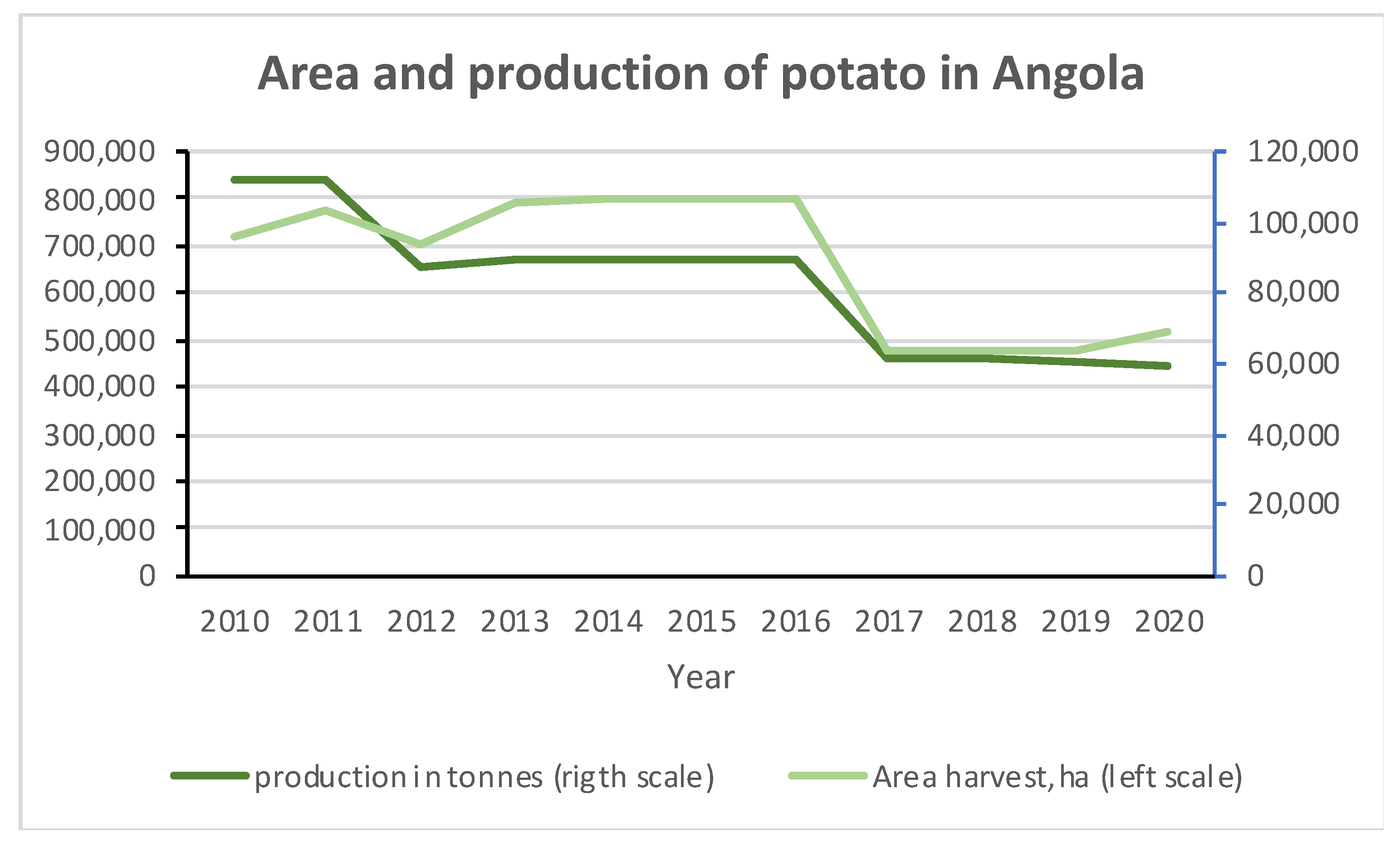

- (4)

- Potato

4. China–Angola Agricultural Cooperation

- (1)

- Stage 1: Infrastructure first

- (2)

- Stage 2: Integrated farm project

5. Methodology

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. SWOT Analysis of China–Angola Agricultural Cooperation

6.1.1. Strengths of Angola’s Agricultural Sector

6.1.2. Weakness of Angola’s Agricultural Sector

6.1.3. Opportunities

6.1.4. Threats

7. Strategies and Recommendations for Agricultural Cooperation between China and Angola

7.1. SO Strategies

7.2. ST Strategies

7.3. WO Strategies

7.4. WT Strategies

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cambuta, G.A. Strategy Options for Angola’s Agricultural Sector after 27 Years of War: A Perception Based Field Study; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ovadia, J.S. State-led development in Angola and the challenge of agriculture and rural development. In Portuguese Studies Review; Newcastle University: Newcastle, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Isaiah Zayone, T.; Henneberry, S.R.; Radmehr, R. Effects of agricultural, manufacturing, and mineral exports on Angola’s economic growth. Energies 2020, 13, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbomba, M.G.; Henriques, P.D.; Rego, M.D.; Carvalho, M.L. Desenvolvimento rural e a redução da pobreza. Rev. Angolana De Sociol. 2009, 4, 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jinyan, Z. Neither’Friendship Farm’nOR’Land Grab:’Chinese Agricultural Engagement in Angola; Johns Hopkins University, School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), China Africa Research Initiative (CARI): Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ngcaweni, B. Analysis of China–Africa cooperation on poverty reduction. In Poverty Reduction in China: Achievements, Experience and International Cooperation; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Aline Carolina da Rocha, M. Desenvolvimento Socioeconômico em Angola: Análise Decolonial dos Investimentos Chineses Direcionados ao Setor Agrícola. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Estadual da Paraíba, Campin Grande, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alden, C. China and the long march into African agriculture. Cah. Agric. 2013, 22, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, L. Chinese agriculture development cooperation in Africa: Narratives and politics. IDS Bull. 2013, 44, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.; Fourie, E. Sino-Angolan agricultural cooperation: Still not reaping rewards for the Angolan agricultural sector. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 2018, 45, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, Q.; Dong, S.; Cheng, H. Agricultural development status and key cooperation directions between China and countries along “The Belt and Road”. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Irkutsk, Russia, 20–26 August 2018; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 19, p. 012058. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I.; Amanor, K.; Favareto, A.; Qi, G. A new politics of development cooperation? Chinese and Brazilian engagements in African agriculture. World Dev. 2016, 81, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Amanor, K.S.; Chichava, S. South–south cooperation, agribusiness, and African agricultural development: Brazil and China in Ghana and Mozambique. World Dev. 2016, 81, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brautigam, D. Will Africa Feed China? Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, S.; Lu, J.; Tugendhat, H.; Alemu, D. Chinese migrants in Africa: Facts and fictions from the agri-food sector in Ethiopia and Ghana. World Dev. 2016, 81, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siméon, N.; Li, X.; Sangmeng, X. China’s agricultural assistance efficiency to Africa: Two decades of Forum for China-Africa Cooperation creation. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 9, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräutigam, D.; Zhang, H. Green dreams: Myth and reality in China’s agricultural investment in Africa. Third World Q. 2013, 34, 1676–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgendi, G.; Mao, S.; Qiao, F. Is a Training Program Sufficient to Improve the Smallholder Farmers’ Productivity in Africa? Empirical Evidence from a Chinese Agricultural Technology Demonstration Center in Tanzania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brautigam, D.; Tang, X. An Overview of Chinese Agricultural and Rural Engagement in Ethiopia. Development Strategy and Governance Division; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoyun, L.; Lixia, T.; Xiuli, X.; Gubo, Q.; Haimin, W. What can Africa learn from China’s experience in agricultural development? IDS Bull. 2013, 44, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, N. An empirical research on agricultural trade between China and “the belt and road” countries: Competitiveness and complementarity. Mod. Econ. 2016, 7, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, E.; Weigert, M. China-Africa Co-Operation beyond Extractive Industries: The Case of Chinese Agricultural Assistance in West Africa; South African Institute of International Affairs: Johannesburg, Sotuh Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tagne, R.F.T.; Dong, X.; Anagho, S.G.; Kaiser, S.; Ulgiati, S. Technologies, challenges and perspectives of biogas production within an agricultural context. The case of China and Africa. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 14799–14826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibonye, V. The Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) and knowledge transfer in Sino-Nigerian development cooperation. Asian J. Comp. Politics 2022, 7, 1045–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Gull, A.; Irfan, S. Sino-African relations: Economic opportunities and challenges for China. Lib. Arts Soc. Sci. Int. J. (LASSIJ) 2019, 3, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräutigam, D.A.; Xiaoyang, T. China’s engagement in African agriculture: “Down to the countryside”. China Q. 2009, 199, 686–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.K.; Hsu, C.; Fan, S. Steadying the ladder: China’s agricultural and rural development engagement in Africa. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2014, 6, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason-D’Croz, D.; Sulser, T.B.; Wiebe, K.; Rosegrant, M.W.; Lowder, S.K.; Nin-Pratt, A.; Willenbockel, D.; Robinson, S.; Zhu, T.; Cenacchi, N.; et al. African farmer-led irrigation development: Re-framing agricultural policy and investment? J. Peasant. Stud. 2017, 44, 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Gashu, D.; Demment, M.W.; Stoecker, B.J. Challenges and opportunities to the African agriculture and food systems. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2019, 19, 14190–14217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimhowu, A. The ‘new’African customary land tenure. Characteristic, features and policy implications of a new paradigm. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason-D’Croz, D.; Sulser, T.B.; Wiebe, K.; Rosegrant, M.W.; Lowder, S.K.; Nin-Pratt, A.; Willenbockel, D.; Robinson, S.; Zhu, T.; Cenacchi, N.; et al. Agricultural investments and hunger in Africa modeling potential contributions to SDG2–Zero Hunger. World Dev. 2019, 116, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, K. The Concept of Corporate Strategy; Dow Jones-Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kangas, J.; Kurttila, M.; Kajanus, M.; Kangas, A. Evaluating the management strategies of a forestland estate—The SOS approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 69, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, R.G. Strategic development and SWOT analysis at the University of Warwick. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 152, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameswari, R.; Silaswara, D.; Andy, A. Swot Analysis of Small and Medium Micro Business Development In Jatiuwung District, Tangerang City. Primanomics J. Ekon. Bisnis 2021, 19, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharachorloo, N.; Nahr, J.G.; Nozari, H. SWOT analysis in the General Organization of Labor, Cooperation and Social Welfare of East Azerbaijan Province with a scientific and technological approach. Int. J. Innov. Eng. 2021, 1, 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, C.; Ettkin, L.P.; Helms, M.M.; Anderson, M.S. The challenge of Venezuela: A SWOT analysis. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2006, 16, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Lu, X.; Shi, M.; Wang, L.; Lv, H.; Chen, S.; Hu, C.; Yu, Q.; da Silveira, S.D.H. SWOT analysis for the development of photovoltaic solar power in Africa in comparison with China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019, 77, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaloo, P.; Siwar, C.; Liong, C.Y.; Isahak, A. Identification of strategies for urban agriculture development: A SWOT analysis. Plan. Malays. 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakosta, C.; Papapostolou, A.; Dede, P.; Marinakis, V.; Psarras, J. Investigating EU-Turkey renewable cooperation opportunities: A SWOT analysis. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2016, 10, 337–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurmanalina, A.; Bimbetova, B.; Omarova, A.; Kaiyrgaliyeva, M.; Bekbusinova, G.; Saimova, S.; Saparaliyev, D. A swot analysis of factors influencing the development of agriculture sector and agribusiness entrepreneurship. Acad. Entrep. J. 2020, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ommani, A.R. Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis for farming system businesses management: Case of wheat farmers of Shadervan District, Shoushtar Township, Iran. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 9448. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud, A.; Şahinli, M.A. SWOT and TOWS analysis: An application to cocoa in Ghana. In Scientific Papers: Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture & Rural Development; Academia: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- D’Silva, R.J. A Case Study of Cashew Industry in Karnataka. Int. J. Case Stud. Bus. IT Educ. 2021, 13, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, M.; Pirdashti, M.; Kennedy, D.T.; Belaud, J.P.; Behzadian, M. A hybrid Delphi-SWOT paradigm for oil and gas pipeline strategic planning in Caspian Sea basin. Energy Policy 2012, 4, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunwolu, Q.A.; Ugwu, C.A.; Alli, M.A.; Adesanya, K.A.; Agboola-Adedoja, M.O.; Adelusi, A.A.; Akinpelu, A.O. Prospects and challenges of cash crop production in Nigeria: The case of cashew (Anacardium occidentale, Linn.). World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2020, 8, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budi, I.; Bhayangkara, W.D.; Fadah, I. Identification of Problems and Strategies of the Home-Based Industry in Jember Regency. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 9, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.B.; Agyekum, E.B.; Adadi, P. Agriculture for sustainable development: A SWOT-AHP assessment of Ghana’s planting for food and jobs initiative. Sustainability 2021, 13, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venda, D.W.d.S. Desempenho da Agricultura Angolana e Suas Potencialidades de Participação no Comércio Internacional; Universidade Federal de Santa Maria: Santa Maric, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CEIC. Relatório Economico de Angola 2019/2020. Available online: http://www.embajadadeangola.com/pdf/RELATORIO-ECONOMICO-2019-2020-VERSAO-FINALISSIMA-18-AGOSTO-2021Relatorio2021_01a264_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Word Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/home (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Ministry of Finance of Angola. Orçamento Geral do Estado. 2021. Available online: https://www.cabrisbo.org/uploads/bia/Angola_2021_Approval_External_BudgetProposal_MinFin_ECCASSADC_Portguese.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Prodesi. Plano de Desenvolvimento de Médio Prazo do Sectors Agrário 2018–2022. Available online: https://prodesi.ao/media/publicacoes/plano-de-desenvolvimento-de-medio-prazo-do-sector-agrario-2018--2022 (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Prodesi. Available online: https://prodesi.ao/ (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Angola’s Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries. Available online: http://www.minagrif.gov.ao/ (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Vines, A. Angola and China: A pragmatic partnership. In US and Chinese Engagement in Africa: Prospects for Improving US-China Africa Cooperation; Centre for Strategic and International Studies: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Finance of Angola. Available online: https://www.minfin.gov.ao/PortalMinfin/#!/ (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Corkin, L. China and Angola-Strategic partnership or marriage of convenience. In Angola Brief; Chr. Michelsen Institute: Bergen, Norway, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Angola Government Portal. Available online: https://governo.gov.ao/ao/ (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China. Economic and Commercial Section, Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Angola. Available online: http://ao.mofcom.gov.cn/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Zhou, J.; He, W. Chinese Cooperation in Mozambique and Angola: A Focus on Agriculture and Health; PUC, BRICS Policy Center: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- China Africa Research Initiative. Available online: http://www.sais-cari.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Rapanyane, M.B. China’s International Relations with Africa: A Comparative Analysis of Neo-Colonial Practices in Angola and the DRC. J. Afr. Foreign Aff. 2023, 10, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Angela, H.; Ward, A.; Chris, A. Chinese Agriculture Technology Demonstration Centres in Southern Africa: The New Business of Development; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, K.D.L.G. Relação China-Angola: Desenvolvimento Socioeconômico Pós-Guerra Civil e os Impactos Positivos e Negativos da Relação Sino-Angolana; Universidade da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira: Redenção, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Safarik, B. Margins of autonomy in the Chinese belt and road initiative: Negotiating growth in rural Angola. In New Nationalisms and China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Exploring the Transnational Public Domain; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Exports of Goods and Services (Current US$)—Angola. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.CD?locations=AO (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Statista. Value of Exports in Angola as of Q3 2021, by Export Partner. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1153826/value-of-exports-in-angola-by-main-export-partners/ (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Comtrade. Available online: https://comtrade.un.org/data/ (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Abplanalp, P.; Lombriser, R. Strategisches Management. Visionen Entwickeln, Strategien Umsetzen, Erfolgspotentiale Aufbauen; Versus Verlag: Zurich, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, P. SWOT analyses and SWOT strategy formulation for forest owner cooperations in Austria. Eur. J. For. Res. 2007, 126, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Stewens, G.; Lechner, C. Strategisches management. Wie Strateg. Initiat. Zum Wandel Führen 2005, 3, 236–239. [Google Scholar]

- Meyo, E.S.M.; Liang, D. SWOT analysis of cassava sector in Cameroon. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Eng. 2012, 6, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar]

- Oladele, O.I.; Sakagami, J.I. SWOT analysis of extension systems in Asian and West African countries. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2004, 2, 232–236. [Google Scholar]

- Thamrin, H.; Herlambang, R.; Brylian, B.; Gumawang, A.K.; Makmum, A. A SWOT analysis tool for Indonesian small and medium enterprise. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2017, 12, 620–625. [Google Scholar]

- Begu, L.S.; Vasilescu, M.D.; Stanila, L.; Clodnitchi, R. China-Angola investment model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINADERP. Plano Bienal do Sector Agrário (2010/2011). 2009. Available online: http://angola.countrystat.org/documents/en/ (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/ (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Chiambo, P.; Coelho, J.; Lima, A.; Soares, F.; Salumbo, A. Angola: Rice crop grow and food security reinforcement. J. Rice Res 2019, 7, 205. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, F.; Carvalho, M.L.d.S.; Henriques, P.D. Contribuição Para o Debate Sobre a Sustentabilidade da Agricultura Angolana; Universidade de Évora: Évora, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jose, d.A.S.T. Agriculture as a tool for development in Angola. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 6642–6650. [Google Scholar]

- MINADERP. Resultados da Campanha Agrícola e da Produção Pesqueira (2010/2011). 2012. Available online: http://angola.countrystat.org/fileadmin/user_upload/countrystat_fenix/congo/docs/RCA%202010.2011.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- MINADERP. Relatório da Campanha Agrícola (2011/2012). 2013. Available online: http://angola.countrystat.org/fileadmin/user_upload/countrystat_fenix/congo/docs/RCA%202011.2012.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- USA Department of Commerce. Angola—Country Commercial Guide. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/knowledge-product/angola-agricultural-equipment (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Abel Chivala Paulo, K. Perspectivas de Evolução da Agricultura na Provincia da Huila em Angola: Caso de Estudo do Perímetro Irrigado da Matala. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Josefa da Graça Fernandes, R. Diversidade das Espécies da Familia Leguminosae com Potencial Agrícola em Angola. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Maize Production in China between 2012 and 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/242367/corn-production-in-china/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Gale, H.F.; Hansen, J.; Jewison, M. China’s Growing Demand for Agricultural Imports, EIB-136, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. February 2014. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/eib-economic-information-bulletin/eib136 (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- McMichael, P. Does China’s ‘going out’strategy prefigure a new food regime? J. Peasant. Stud. 2020, 47, 116–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Agricultural Development in China and Africa: A Comparative Analysis; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Morshed, M. China’s Agriculture “Going Out” Strategy beyond Resource Constraints and Unbalanced Trading. Am. J. Trade Policy 2018, 5, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erokhin, V.; Gao, T. Impacts of COVID-19 on trade and economic aspects of food security: Evidence from 45 developing countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuur, J.; Koks, E.E.; Hall, J.W. Observed impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on global trade. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-18-january-2022 (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Mertz, O.; Halsnæs, K.; Olesen, J.E.; Rasmussen, K. Adaptation to climate change in developing countries. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luís, J.C. Impactes das Mudanças Climáticas Projetadas na Distribuição de Espécies Arbóreas no Sudoeste de Angola. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Biagini, B.; Miller, A. Engaging the private sector in adaptation to climate change in developing countries: Importance, status, and challenges. Clim. Dev. 2013, 5, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | GDP Billion (USD) | GDP Per Capita (USD) | Population, Total (Billion) | Urban Population (% of Total Population) | Rural Population (% of Total Population) | Employment in Agriculture (% of Total Employment) | Agriculture Value Added (% of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 81.70 | 3.497431 | 23.36 | 59.8 | 40.2 | 48.9 | 6.2 |

| 2011 | 109.44 | 4.511129 | 24.26 | 60.5 | 39.5 | 51.2 | 5.8 |

| 2012 | 125.00 | 4.962286 | 25.19 | 61.3 | 38.7 | 51.2 | 6.1 |

| 2013 | 133.40 | 5.101338 | 26.15 | 62.0 | 38.0 | 51.2 | 6.5 |

| 2014 | 137.24 | 5.058606 | 27.13 | 62.7 | 37.3 | 51.1 | 7.5 |

| 2015 | 87.22 | 3.100604 | 28.13 | 63.4 | 36.6 | 51.2 | 9.1 |

| 2016 | 49.84 | 1.709777 | 29.15 | 64.1 | 35.9 | 51.2 | 9.8 |

| 2017 | 68.97 | 2.283018 | 30.21 | 64.8 | 35.2 | 51.0 | 10.0 |

| 2018 | 77.79 | 2.487687 | 31.27 | 65.5 | 34.5 | 50.9 | 8.6 |

| 2019 | 69.31 | 2.142503 | 32.35 | 66.2 | 33.8 | 48.9 | 6.7 |

| 2020 | 53.62 | 1.603948 | 33.43 | 66.8 | 33.2 | 50.8 | 9.5 |

| Agricultural Resources | Description |

|---|---|

| Arable land area | Angola has a total geographic area of 1.2467 million km2 with approximately 58 million ha of arable land, and only 5,673,259 ha were cultivated in 2017–2018. Of the total cultivated area, 92% was done by family farming, and commercial farms cultivated the remaining area. |

| Water resources | The country had more than 148.4 billion m3 of renewable water resources available in 2018, of which less than one percent is withdrawn annually. About two-thirds of the total water withdrawal is used in agriculture each year. |

| Irrigated area | In Angola, agriculture is predominantly rainfed; only about one percent of the cultivated area is irrigated annually. |

| Population | About 33% of the population lives in rural areas, and they are directly involved in the agriculture sector. Family farming is the basis of Angolan agriculture, responsible for more than 80% of the national agricultural production and about 97% of the total area under exploration. |

| Industry | Total Value (Million USD) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Municipal works | 905.5 | 20 |

| Education | 642.5 | 14.2 |

| Transport | 572.8 | 12.6 |

| Agriculture | 530.6 | 11.7 |

| Energy | 514.1 | 11.3 |

| Health | 409.3 | 9 |

| Telecommunication | 408.2 | 9 |

| Livelihood project | 270 | 5.8 |

| Water supply | 252.8 | 5.5 |

| Justice | 41.1 | 0.9 |

| Total | 4547 | 100 |

| Name of the Farm | Geographical Position | Investors | Type of Company | Project Start Date | Line of Credit (Million USD) | Farm Size (ha) | Plant Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedras Negras | Malange | CITIC Construction | state-owned enterprise | 2011 | 160 | 12,580 | corn, soybean |

| Sanza Pombo | Uige | CITIC Construction | state-owned enterprise | 2012 | 129 | 1610 | rice, cattle |

| Longa | Cuando Cubango | CAMC Engineering | state-owned enterprise | 2012 | 77.6 | 1500 | rice |

| Kamacupa | Bie | CAMC Engineering | state-owned enterprise | 2012 | 88.64 | 4500 | corn, |

| Guimba | Zaire | CEIEC | state-owned enterprise | 2014 | 68 | 3000 | Corn, Soybeans |

| Camaiangala | Moxico | CEIEC | state-owned enterprise | 2013 | 79 | 3000 | Corn, Soybeans |

| Manquete | Cunene | CEIEC | state-owned enterprise | 2014 | 45,000 | rice |

| Strengths (Internal) | Weaknesses (Internal) |

|---|---|

| Which advantages of the cooperation are there? What has been done well? What do others see as advantages for the cooperation? | Which drawbacks of the cooperation are there? What can be done better? What should not occur? |

| Opportunities (external) | Threats (external) |

| What factors have a favourable impact on cooperation? What are the potential opportunities for that cooperation? Which opportunities can arise from trends when the two countries corporate? | Are there any barriers that could threaten China and Angola’s agricultural cooperation? |

| Strengths of Angola’s Agricultural Sector | Weakness of Angola’s Agricultural Sector | |

|---|---|---|

| S1. Good agricultural resource endowment S2. Has a good foundation for cooperation S3. Land ownership is clear S4. Human resources are abundant and relatively cheap | W1. Poor infrastructure W2. Primitive mode of production and serious shortage of input in agricultural production W3. Weak technical force and lack of technical support for agricultural production | |

| Opportunities | SO strategies | WO strategies |

| O1. Great potential for agricultural development O2. The advance of China’s agricultural technology O3. Food security is due to the Chinese economy | SO1. Expand the scale of Angola’s food production SO2. Strengthen cooperation in the construction of agricultural demonstration parks | WO1. Priority to carry out joint farming in areas with relatively perfect infrastructure |

| Threats | ST strategies | WT strategies |

| T1. The global COVID-19 outbreak in 2019 T2. Climate change | ST1. Establishment of sustainable modern agricultural production management system | WT1. Overall implementation of comprehensive agricultural cooperation projects WT2. Strengthen the government’s comprehensive support for agriculture |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cabral, F.D.F.; Yin, C.; Wague, J.L.T.; Yin, Y. Analysis of China–Angola Agricultural Cooperation and Strategies Based on SWOT Framework. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108378

Cabral FDF, Yin C, Wague JLT, Yin Y. Analysis of China–Angola Agricultural Cooperation and Strategies Based on SWOT Framework. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):8378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108378

Chicago/Turabian StyleCabral, Flavia Darcy Ferreira, Changbin Yin, Johan Landry Tchantchou Wague, and Yanshu Yin. 2023. "Analysis of China–Angola Agricultural Cooperation and Strategies Based on SWOT Framework" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 8378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108378

APA StyleCabral, F. D. F., Yin, C., Wague, J. L. T., & Yin, Y. (2023). Analysis of China–Angola Agricultural Cooperation and Strategies Based on SWOT Framework. Sustainability, 15(10), 8378. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108378