Abstract

The sharing economy relating to e-hospitality is threatened globally with sanctions and closure owing to incessant noise and partying complaints, as well as complaints relating to reckless driving, tax evasion, and its social and economic effect on residents and accommodation vendors of longer stay rentals. Because the government is seeking a balance in regulating the e-hospitality sector, we sought to explore how professionalism of the e-hospitality platforms could potentially contribute to the sustainable growth of the sector in local and regional communities. In our study we developed a conceptual narrative that distinguishes two dimensions of professionalism for the sharing economy, namely the ticket clipper and end-to-end model. Data for the research was obtained from Vacation Rental Data (Airdna). Airdna provides a databank for both Airbnb and VRBO/Stayz. For the study a dataset from Airdna for HomeAway, also popularly known as Stayz, was utilized as a representative sample from a tourism town in Western Australia. For analysis of the dataset, path/panel regression was utilized, with a hierarchical linear model subsequently adopted for cross-section and multi-sectional analysis. Findings in the study demonstrate that professionals tend to improve the overall rating, and where the overall rating mediates the relationship between management firm (property/apartment/accommodation venue) and price. It was further observed that no relationship exists between overall rating and the number of HomeAway supply types; nevertheless, professionals promote the image and reputation of the property. Contrary, bad, or negative e-hospitality reviews lead to avoidance by prospective visitors. Lastly, results from the study took the form of two theoretical contributions, namely the ticket clipper model and the end-to-end model. More complaints were received concerning ticket clippers and it was noted that this model has caused severe shutdown in several cities and regions. The end-to-end model appears to be more sustainable. Moreover, literature suggests that there are more complaints from residents concerning ticket clippers and it was noted that this model has caused severe shutdown in several cities, nonetheless the end-to-end model appears to be more sustainable.

1. Introduction

The sharing economy has become increasingly popular in recent years and exerts a significant impact on the economy and society. While the sharing economy offers many benefits in the e-hospitality sector, such as increased access to goods and services and new economic opportunities, there are also trust, safety, and professionalism deficit (Ndaguba, 2023) [1]. Cancellations and guest requests for refunds create considerable dissatisfaction among Airbnb hosts (Huang, Coghlan & Jin, 2020) [2], while reckless driving and the COVID-19 pandemic created anxiety among residents of areas in which Airbnbs operate (Czarnecki, Dacko & Dacko, 2023) [3].

Allegations of a lack of regulation, the absence of quality control, the knowledge gap of hosts, noise pollution, and inadequate communication and transparency of both platform and host (Cheng, Mackenzie & Degarege, 2022) [4]. In cities such as San Francisco, Tokyo, Barcelona, and Sydney residents have fallen out with the users of the sharing platform for accommodation purposes (see Figure 1). This fallout has created a gap that property managers or management firms acting as professionals can leverage on, to provide a bridge between host and platform, host and communities, and communities and platforms.

Figure 1.

Protests against short-stay accommodation. Source: Authors’ compilation of Airbnb events.

Hence, the study aim is to use professionals as liaison officers in reducing the tension and pressure between residents and short-stay providers stakeholders in the sharing platform sector. In other words, how can professionalization of the sharing platform contribute to the growing debate regarding the shutdown of sharing platforms due to non-sustainability practices (Shan, He & Wan, 2023) [5].

According to Zeqiri, Dahmani and Yousse (2021) [6] the e-hospitality sector draws on the potential of knowledge management or the means through which professionals in the e-hospitality venture can leverage technology to share and manage knowledge management. Similarly, Sigala (2017) [7] argues that e-hospitality entails the use of technology to enhance the hospitality industry, particularly in the areas of guest services, operations, and marketing. Furthermore, Choi and Lee (2017) [8] describe professionalism in e-hospitality as the ability of hospitality professionals to use technology in a competent and efficient manner to enhance guest experiences and operational efficiency. Hence, e-hospitality deals with online or electronic or digital platforms within tourism and the hospitality sector. In many instances the digital platform does not own the properties that are advertised there; the property owner or the host owns the vacation property, which then is advertised on the digital platform (Ndaguba, 2023) [1].

However, there are some obstacles to professionalizing e-hospitality, among these being the high cost of technological adoption, data security and privacy, the need for training, and the integration of existing technological systems (Sigala, Rahimi & Thelwall, 2019) [7]. Regarding e-hospitality in the digital era, Brandão, Costa & Buhalis, (2018) [9] and Kim (2019) [10], while agreeing with Sigala et. al. [7], further emphasize the importance of balancing technology with personal service to ensure customer satisfaction in e-hospitality. Creating a balance between technical aspects and care management requires an astute administrator knowledgeable regarding technology and experienced in delivering guest satisfaction.

Research shows that scholars have directed a great deal of attention towards guest satisfaction, in addition to revenue management (Fyall, Legoherel, & Poutier, 2013; Gibbs, Guttentag, Gretzel, Yao, & Morton, 2018) [11,12], reputational management (Davies & Miles, 1998; Gandini, 2016; Luca & Svirsky, 2020) [13,14,15], value co-creating (Lalicic, Marine-Roig, Ferrer-Rosell, & Martin-Fuentes, 2021; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004) [16,17] and trust (Agag & El-Masry, 2017; Arvanitidis, Economou, Grigoriou, & Kollias, 2020; Bicchieri, Duffy, & Tolle, 2004; Ert & Fleischer, 2019) [18,19,20,21]. There are only a few studies discussing professionalism in the context identified here, and when such scholars (Deboosere, Kerrigan, Wachsmuth, & El-Geneidy, 2019) [22] discuss professionalism, it tends to be in relation to a host having two or more holiday homes, which is hardly an accurate representation of what professionalism connotes.

Nevertheless, within the contemporary philosophy of professionalism for the sharing economy, there exist two schools of thought. The first aligns with Casamatta, Giannoni, Brunstein, and Jouve’s (2022) [23] association of professionalism with a number of listings, or supply types, which set a threshold for hosts or property owners possessing two or more properties (Gurran & Phibbs, 2017; Li, Moreno, & Zhang, 2016; Oskam, van der Rest, & Telkamp, 2018) [24,25,26]. The second school considers the threshold to be three and above. This implies that if a host/owner is able to own two or three apartments, they may be classified as being a professional and exemplifying heightened levels of professionalism within property and care management (Casamatta et al., 2022) [23]. Following this logic, it could then be claimed that those who have two or more cars are expert drivers–which may be far from the truth. Both schools of thought therefore lack an understanding of what professionalism denotes in the sharing platform context. The notion of professionalism relates to competence in a skill required of an individual or agency which is based on certain qualities, know-how or qualification (Naidoo, 2016) [27]. In e-hospitality a professional is understood to be a manager or management company who is involved in the daily affairs of a vacation home, having the requisite qualification and competence to carry out these functions and responsibilities in e-hospitality and care management (Naidoo, 2016) [27].

Hence, professionalizing the sharing economy requires a multifaceted approach that involves developing clear regulations, implementing quality control measures, enhancing communication and transparency, training, and education, adhering to industry standards, and improving reputation systems. These measures can help promote trust, safety and credibility among users and ensure that the sharing platforms continue to grow and evolve in a professional manner. The lack of regulatory oversight in the industry has the potential to give rise to safety concerns, unfair competition, and discrimination (Botsman, 2013) [28]. Furthermore, the lack of standardization codes and protocols, quality controls and certification processes to ensure that hosts are meeting minimum standards of safety, authenticity and cleanliness have contributed to the call for professionalism (Guttentag, 2015; Martin & Upham, 2019) [29,30]. However, issues of labor rights and protection are some of the major obstacles to professionalization of the sector (Martin & Upham, 2019) [30].

This paper is organized in the following manner. Following a discussion of the need for professionals and professionalism in the sharing economy within the e-hospitality sector, literature pertaining to the sharing economy is examined, beginning with the global context, and working towards the narrower perspective of Augusta–Margaret River, and the antecedents of the sharing platforms in e-hospitality. After the literature section, the paper sets out the methodology adopted for the study, detailing the mode of data collection, and then dealing with the use of secondary data in previous academic studies examining the hospitality sector. An analysis of the data collected is then presented in the results section, with analysis being based on a path analytical framework, before an analysis of the data using the hierarchical linear model is offered. The theoretical and managerial perspective are presented in the section that follows, and the concluding remarks include the limitations of the study and a synthesis of the findings from the data generated.

2. Related Literature

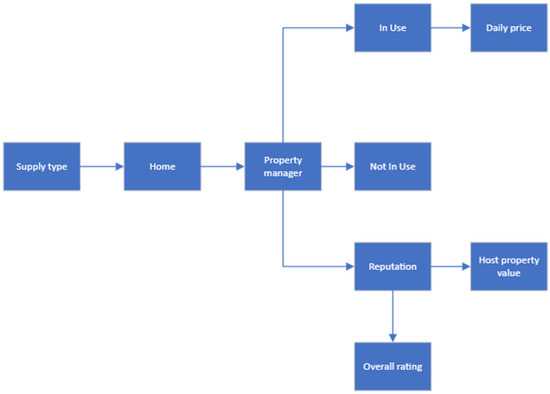

The literature presented covers four themes. The first of these is the sharing economy. The argument here is that the digital platform for accommodation in the hospitality sector is a subset of the sharing economy ecosystem, which has its roots in the old economic ordinances of the barter system (Belk, 2007) [31]. The transformation or novelty of the new system lies in the increasing adoption of technology as a medium of exchange. The second theme is the growth and expansion of the sharing economy with reference to its antecedents. The third is the theoretical perspectives for rationalizing the concept of individuals allowing strangers as guests to utilize their property. The fourth theme is the professionalization of the sharing economy. Here perspectives are offered on the gains and challenges associated with professionalizing a sector which has enormous economic opportunities, and which is related to numerous social and environmental issues. These themes are critical to an understanding of the conceptual framework demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework for professionalizing the sharing economy. Source: Authors configuration.

2.1. Sharing Economy

Recent research on the sharing economy in tourism and hospitality has placed considerable emphasis on two main aspects in disruptive science, namely ridesharing (such as Uber and Lift) and e-hospitality (such as Airbnb and Stayz). Further, within e-hospitality, the focus is on Airbnb (Adamiak, 2018; Boros, Dudás, Kovalcsik, Papp, & Vida, 2018; Dogru, Mody, Suess, Line, & Bonn, 2020) [32,33,34]. Despite the existence of multiple e-hospitality sharing platform providers, Airbnb has been the most discussed and analyzed, giving it a competitive advantage. Ten times more research is conducted on Airbnb than on other digital service providers. In practical terms, the greater research emphasis on Airbnb creates bias in the host who intends to explore options or is in search of the right fit for promoting their vacation home. Although Airdna provides a databank for both Stayz and Airbnb, data for Airbnb outweighs that for Stayz, despite research by Agarwal, Koch, and McNab (2019) [35] revealing a plethora of inadequacies and anomalies in the Airdna database.

The sharing economy is a renewed economic practice or model that emphasizes resources or access, rather than ownership. The novelty of the sharing economy has also helped enhance the circular economy and the experience economy. The sharing economy as it is known today has developed and scaled as a result of the use and penetration rate of the internet, which has not only aided the growth of the sharing economy but has also had an important effect on the transformation of the global economy. For instance, within the financial sector, there has been a drastic shift from investment in financial stocks to blockchains and, more recently, cryptocurrencies (Huckle, Bhattacharya, White, & Beloff, 2016) [36]. This effect has also been felt in the diversification of economies from mono-economies to gig economies (Steinberger, 2018) [37], and, through the utilization of sharing platforms via the internet, hotel-like structure for visitor stays are adopting the trends and styles of the e-hospitality sector (Guttentag, 2015; Udéhn, 1993) [29,38]. Further to adopting e-hospitality trends, the sharing economy has introduced the notion of access over ownership through technological innovation (Belk, 2007; Botsman & Rogers, 2010; Rinne, 2019) [31,39,40]. Technological change and innovation have been adopted as disruptive techniques, which has led to a new model or paradigm for businesses within the sharing economy.

In the 21st century, there has been a rise in digital disruption, which has implications for sectors with a human slant, such as music and video coverage, and streaming services (Botsman & Rogers, 2010, 2011; Zentner, 2006) [39,41,42], transportation (Christensen, Raynor, & McDonald, 2015; Zeleny, 2012) [43,44], and open-source publishing. A measure of disruption has also had an impact on manufacturing (Pattinson & Woodside, 2008; Zeleny, 2012) [44,45], consumer consumption and education (Al-Imarah & Shields, 2019; Ellis, Souto-Manning, & Turvey, 2019; Ellis, Steadman, & Trippestad, 2019) [46,47,48], and communication (Latzer, 2009; Pegoraro, 2014) [49,50]. Data management, storage and transfer including computing have transformed significantly (Cãtinean & Cândea, 2013) [51]. Furthermore, other sectors, such as drug manufacturing, tourism (Fayos-Solà & Cooper, 2019; Guttentag, 2015; Guttentag & Smith, 2017; Romero & Tejada, 2019) [29,52,53,54], and the housing sector have also witnessed their fair share (Brown et al., 2019; Campbell, McNair, Mackay, & Perkins, 2019) [55,56].

E-hospitality has two main stakeholders, Airbnb and VRBO, for data management and storage held by Airdna. The e-hospitality initiative has transformed the mode of operation of most hospitality businesses or providers, which have now moved away from manual operability in the sector. Owing to global interdependence and interconnectedness faster modes of operation are consistently adopted for effective service delivery. The need for adequate and faster response rates and higher efficiency of tourist booking activities, quicker turnaround time for transactions, and the increased need for collaboration and partnership rather than ownership lie at the heart of disruptive innovation and the need for technological change and adoption (Pérez, Geldes, Kunc, & Flores, 2019; Pérez, Dos Santos Paulino, & Cambra-Fierro, 2017) [57,58], providing speedy and innovative mechanisms for advancing collaboration, co-production, and the circular economy. The sharing economy has many characteristics; however, its rapid growth has been controversial in that it is not universal, but has been characteristic only of certain hosts, who have choice houses in choice areas. Thus, there is a need for literature to provide further information. In the art and management of the business operations of Airbnb, access over ownership as demonstrated by Belk (2007) [31] remains a critical front alliance for understanding Airbnb and digital commerce. However, before we proceed to a discussion of the access over ownership theorem, the antecedents of the sharing economy offer background to the character and history of digital commerce as these relate to e-hospitality.

2.2. Antecedents of the Sharing Economy

The sharing economy within the context of e-hospitality as known today first arose in San Francisco, in the United States (Schor, 2016) [59]. However, it has grown beyond all expectation, its expansion and accessibility in advancing the digital platforms reaching unprecedented levels (Brown et al., 2019) [60]. due to the increased penetration and usability of e-hospitality, users of the internet increased by 7% between 2018 and 2019 (4.021 billion users), and this has created greater opportunities for the sharing platforms and for dialogue between the communities/neighborhoods that participate in the sector, owners/hosts of properties in the neighborhoods, and government and associations that have an influence in decision-making on the rationale for the operability of the sharing economy within their territory. Since laws on the sharing economy in the e-hospitality sector are decided locally, whereas some countries such as America have an overall framework, Australia does not (Brown et al. 2019) [60]. In response to opportunities presented by sharing platforms through internet penetration, the number of social media users is understood to have increased by 13%, while the number of mobile phone users also blitzscaled by 4% globally in 2018 (Kemp, 2018) [61]. These indices show that access to social media and mobile operators have brought more people to recognize and use the sharing economy, whose culture has also been captured by social media giants such as Facebook and Twitter. These media giants do not provide or pay for content, because their entire machinery is predicated on users sharing their daily lives, experiences, and activities on a social media platform.

The growth in the number of Internet users has a direct bearing on the growth of the sharing economy initiative. As Lamberton and Rose (2012, p. 109) [62] assert, the growth in the sharing initiative is a consequence of the usability of social media (Galbreth, Ghosh, & Shor, 2012; Gansky, 2010) [63,64]. Several authors have suggested that the sharing economy concept is not in fact new (Belk, 2014; ter Huurne, Ronteltap, Corten, & Buskens, 2017) [65,66]; however, Brown et al. (2019) [60] argue that the idea of the sharing economy is still in its formative stage, and that it will soon transform or metamorphose into something completely different, where content may be provided at a cost. This will pave the way for the globalization of sharing enthusiasts to become sharing content entrepreneurs. This idea is not merely predicated on numbers of views or streams, but on contracts, such as Netflix does with Comedy Specials.

2.3. Access over Ownership in the Australian Market

Access over ownership is a trend that is growing in the Australian market, and one of the best-known examples of this is Airbnb. Airbnb is a sharing economy platform that allows individuals to rent out their homes or spare rooms to travelers, providing an alternative to traditional hotel accommodation (Belk, 2018) [67].

One of the primary benefits of access over ownership through Airbnb is cost savings. According to research by Airbnb, the average host in Australia earns AUD 7100 per year by renting out their home or a room (Airbnb, 2019) [68]. This can represent a significant additional income stream for individuals, particularly in areas such as tourist destinations, where demand for accommodation is high. For travelers, Airbnb can provide a cost-effective alternative to traditional hotel accommodation, particularly for longer stays.

In addition to cost savings, Airbnb also offers increased convenience for both hosts and guests. For hosts, renting out their property can provide a passive income stream, without the need to actively manage the property on a day-to-day basis (Belk, 2007) [31]. Airbnb also provides hosts with the ability to set their own availability and pricing, giving them greater control over how their property is used. For guests, Airbnb offers a wider range of accommodation options than traditional hotels, including unique and quirky properties such as treehouses and houseboats (Bao, Ma, La, X.u & Huang, 2022) [69].

Access over ownership through Airbnb is achieved through the social and cultural connections that can be made through the platform. E-hospitality allows guests to stay in local neighborhoods and experience the city as a local rather than as a tourist (Aversa & Rice, 2023) [70]. This can provide a more authentic and immersive travel experience and can also foster relationships between hosts and guests. Airbnb (2019) [68] reports that 60% of Australian hosts say that they have formed lasting friendships with guests.

Access over ownership through Airbnb can also have positive effects on local economies. According to research by Airbnb, the platform generated AUD 4.4 billion in economic activity in Australia in 2019, with the majority of this activity taking place outside of major tourist destinations (Airbnb, 2020) [71]. This can provide a significant economic boost to local communities, particularly in regional areas.

However, access over ownership through Airbnb is not without its challenges. One of the primary concerns relating to Airbnb is its impact on the availability and affordability of rental housing. Some critics argue that Airbnb drives up rents by reducing the supply of long-term rental properties and encouraging landlords to convert properties into short-term rentals (Shan, He & Wan, 2023) [5]. This can have negative impacts on housing affordability, particularly in areas where demand for housing is high, such as Perth, Sydney and Melbourne (Carollo et al., 2023) [72].

To curb the excesses of e-hospitality, issues of legality and zoning laws have become a public debate. Where there are local laws, there is hardly any update and, in some cases, the monitoring and enforcement agencies responsible for implementing the laws are inactive, lack the skillset or expertise required, and have a low capacity to function.

Overall, access over ownership through e-hospitality offers numerous benefits for both hosts and guests, including cost savings, increased convenience, social and cultural connections, and economic benefits. However, the platform also presents challenges in terms of its impact on the housing market. As the sharing economy continues to grow, it is likely that access over ownership through platforms such as Airbnb and Stayz will become an even more prevalent trend in the Australian market, changing the way that individual’s access and use accommodation.

2.4. Professionalism of the Sharing Economy

The assumption about professionalism is likened to supplies or listings of vacation homes; if the number of homes an owner has equates to the notion of professionalism, then the concept of professionalism may have been misaligned within the sharing economy discourse. Li and Srinivasan (2019) [73] define Airbnb supply as the number of active listings that are either booked or available for vacation stay. While the definition relates to availability of guest-stay denotationally, Merriam-Webster defines professionalism as “the conduct, aims, or qualities that characterize or mark a profession or a professional person”, while a profession refers to “a calling requiring specialized knowledge and often long and intensive academic preparation” (Porcupile, 2015:1) [74]. The denotational definition demonstrates that professionalism entails a multiplicity of capabilities and capacities, such as competence, specialized knowledge, integrity and honesty, accountability, image, and self-regulation (Porcupile, 2015) [74], which is inconsistent with Li and Srinivasan’s definition of professionalism within property management of accommodation listings. Managing or owning two or more properties does not signify competence or specialized knowledge, nor are these demonstrated by the fact that most Airbnb owners also have other commitments or jobs, or that many do not reside where they have their apartment or holiday home. In a multi-billion-dollar activity, the need for agents, agencies and professionalism in the e-hospitality sector cannot be overemphasized. This makes it difficult, if not impossible, for e-hospitality owners to advance this sector without some degree of professionalism in their daily activities.

Professionalism relates to competence, or a skill required of an individual or agency which is based on certain qualities, know-how or qualification (Naidoo, 2016) [27]. A professional in e-hospitality is a manager or management company displaying conduct expected of a competent individual or agency in a learned profession, such as in hospitality and care management (Naidoo, 2016) [27] under whose authority an end-to-end service is delivered to guests; in this they differ from ticket clippers, who simply book the ticket.

The first model is known as the booking channels or ticket clippers model, and it involves those organizations that provide a one-way e-hospitality traction in the accommodation business, for instance through providing ticketing or organizing booking at a fee, usually capped at between 12% and 18%, without providing further services to the guest until they are granted access. The second e-hospitality model is an end-to-end model, which entails a closer relationship with guests. End-to-end providers are firms or agencies that concern themselves with the entire ecosystem of the sharing platform in the e-hospitality sector. They provide marketing services for the accommodation, booking services, cleaning services, laundry services, and the general maintenance and care of the property, and are heavily taxed in comparison to ticket clippers. Thus, the end-to-end providers are usually seen to provide a professional service to guests in that most professionals engage within the entire fabric or ecosystem of the sharing economy, from pickup, welcoming and transport services to the apartment preparation and advertising, and they usually have their own sites. Therefore, although professionalism is conceived as a broad concept which deals with the aims, conduct and qualities of a professional, embodying positive habit, conduct, perception, and judgement as either an individual or an agency in dealing with the daily tasks relating to an apartment or accommodation, our research suggests that end-to-end providers adopt the tenets of e-hospitality professionalism by providing services ranging from welcoming to marketing, and maximizing revenue and price returns to homeowners, which is consistent with ethical considerations and standards for responsible hosting in the digital market space (Wagner, Huber, Sweeney & Smyth, 2005; Rowley, 2008) [75,76].

2.5. Formulation of Hypotheses

Before the introduction of the research methodology applied, based on the assumptions of the sharing economy, the following hypotheses can be formulated.

Hypothesis formulation:

The rationale for this arrangement is based on the logical flow of the hypotheses, from the more general to the more specific.

Hypothesis 1.

Supply type in e-hospitality plays a critical role in price determination.

The supply type in e-hospitality, particularly in the sharing economy, plays a critical role in price determination. According to a study by Guttentag (2015) [29], peer-to-peer accommodation, such as Airbnb, is generally cheaper than traditional hotels. This is because peer-to-peer accommodation offers a more personalized and authentic experience, although it may lack some of the amenities and services provided by traditional hotels.

Furthermore, the location of the accommodation can also affect price determination. According to a study by Kim, Vogt and Knutson (2015) [77], properties located in popular tourist destinations or in areas with high demand generally command higher prices than those in less popular areas.

Hypothesis 2.

Professionals in the sharing economy improve the daily price of host properties.

Several studies have shown that professionals within the sharing economy play a significant role in improving the daily price commanded by the host properties. According to a study by Wang et al. (2019) [78], Airbnb hosts who included professional quality photographs on their property listings commanded higher daily rental rates than those with non-professional photos. Another study by Deboosere et al. (2019) [22] and Barnes and Kirshner (2021) [79], found that hosts with a higher response rate, verified identification, and more reviews commanded higher prices for their listings.

Additionally, Airbnb’s Superhost program has been found to positively affect host prices. According to a study by Chen and Xie (2017) [80] and Li, Li, Liu and Fan (2023) [81], Airbnb Superhosts commanded higher prices than non-Superhosts. This can be attributed to the fact that Superhosts are recognized by Airbnb for their high level of hospitality and service, which in turn increases their credibility and trustworthiness among potential guests.

Hypothesis 3.

Reputation of a property in the e-hospitality sector is significantly associated with the overall rating of the accommodation.

The reputation of a property in the e-hospitality sector is significantly associated with the overall rating of the property. According to a study by Wang et al. (2019) [78], Airbnb host ratings were positively associated with the overall quality of the listing, including factors such as accuracy of the description, cleanliness, and amenities.

Similarly, a study by Xie and Chen (2019) [82] found that the overall rating of an Airbnb listing was positively associated with host communication skills and responsiveness, as well as the quality of the listing itself.

Hypothesis 4.

Professionals in the sharing economy improve the reputation of host property value.

Similarly, professionals within the sharing economy play a critical role in improving the reputation of host properties. According to a study by Cheng and Edwards (2019) [83], Airbnb host ratings were positively associated with host professionalism, responsiveness, and communication skills. In another study by Lin et al. (2020) [84], it was found that hosts with a higher number of reviews had better ratings, indicating that guest feedback is an important factor in determining a host’s reputation.

Furthermore, Airbnb’s Superhost program has been found to improve the reputation of host properties. According to a study by Do, Pereira and Silva (2023) [85], Superhosts who had higher ratings were more likely to receive positive reviews than non-Superhosts. This can be attributed to the fact that Superhosts are recognized by Airbnb for their high level of hospitality and service, which in turn increases their credibility and trustworthiness among potential guests.

In other to synthesize the outcome for postulating the conceptual framework (Figure 1), we provided a summary of the hypotheses, building on the sharing economy, its antecedents, the theoretical perspective about access over ownership, and the need for or benefits of professionalizing the e-hospitality sector. Within the discourse, some variables were used more repeatedly; these included supply type; digital accommodation; property managers, whom we refer to as professionals; reputational variables such as overall ratings, number of reviews, and Superhost. Managerial variables such as daily price, revenue and occupancy rate were also identified. Nonetheless, because the study was limited to evaluating professionalization as a means towards sustainable economic benefits for communities, the hypotheses created a picture of what we intended to examine.

Summary of Hypotheses

- ▪

- Supply type in e-hospitality positively influences price determination.

- ▪

- Professionals in the sharing economy have a positive effect on the daily price of host accommodation.

- ▪

- Reputation of a property in terms of ratings in the e-hospitality sector has a significant association with host supply.

- ▪

- Property managers in the sharing economy are significantly associated with host property value (revenue).

3. Methodology

Previous studies have used either a qualitative (Huang, Coghlan, & Jin, 2020) [2] and/or a quantitative (Guo, Liu, Song, & Yang, 2022; Lutz & Newlands, 2018) [86,87] approach to Airbnb research in tourism and the hospitality sector using the Airdna database. Given the amount of research output on the topic of e-hospitality, understanding professionalism in the sector is germane to further expanding the discourse on sharing platform research. For the study the hierarchical or nested regression approach, which is not a commonly used instrument within sharing economy and hospitality research, was adopted. One of the primary advantages of hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) is that it allows for the analysis of data with multiple levels of variability. Further to the novelty of the method used, professionalism in relation to property managers or management firms has not previously been utilized in HLM. It was thus hoped that the quantification of this inquiry would complement existing research within the field. The steps followed are introduced as they were applied in the research.

3.1. Data Collection

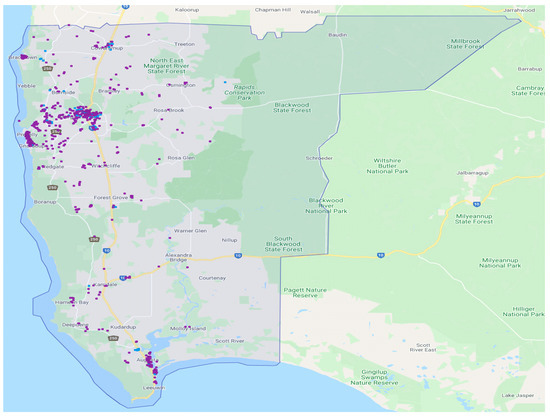

Data was sourced from the Airdna database on 18 May 2021. The database consisted of information regarding Airbnb activities in the Margaret River region between 2012 and 2019. Figure 3 below demonstrates the geographical spread of the 253 Airbnb suppliers in the region as at February 2021 (Airdna, 2022) [88]. The dataset showed that demand for Airbnb properties averaged 70%, with an average daily rate of AUD268, and a monthly average of about AUD4,370 (Airdna, 2022) [88]. The literature is saturated with three kinds of Airbnb supplies, namely private rooms, shared rooms, and entire private rooms. The drivers of e-hospitality in Australia’s regions are largely the entire home option, which differs from the situation in America (Dogru, Hanks, Mody, Suess, & Sirakaya-Turk, 2020) [89], where shared rooms are popular alongside private rooms. In Margaret River, entire homes are the most preferred in comparison with private rooms, while shared rooms are not commonly used by visitors. For example, data from Airdna (2022) [88] suggests that private rooms constitute about 8% of the market share, which is another motivation for sampling entire homes only. Research papers for this study were gathered in Dimensions, and the study followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) protocol (Sin, Tan, & McPherson, 2021) [90] (see Figure 3). A scientometric analysis was adopted to select target literature based on the aims of the research. Figure 3 illustrates how data was collected from Digital Science & Research Solutions Inc. (2021) [91].

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of Airbnb in the Margaret River regional area. Source: Airdna (2022) [88].

Several factors such as rental demand, revenue growth, seasonality, regulation, and investability are the major components shaping the market grade for the utilization of properties in the sharing economy. For instance, 26% of advertisers in the region market their properties on both Airbnb and VRBO, while 14% use VRBO, 60% adopt Airbnb. The data further demonstrates that guest ratings are predicated on cleanliness, communication, location, value, accuracy, and check-in times. Similarly, guests make choices of where to stay based on amenities available at the property and in its environs, including the number of bedrooms. Other variables may include the nature of the cancellation policy and the length of stay; for instance, the dataset shows that a greater number of hosts opt for a strict cancellation policy (43%), while 28% and 20% of hosts adopted moderate and flexible cancellation policies respectively. Length of stay may also be a factor, where approximately 59% of hosts require a minimum stay duration of two or more days (Airdna, 2022) [88].

Preceding analyses relating to overall rating, minimum stay, demand, ADR, revenue, rental/listing type and reservation circle show that length of operation plays a significant role in shaping the Airbnb prosperity assumption. Airbnb prosperity can be described as areas where Airbnb operators are more likely to succeed or are more successful. For this reason, for the study virtually all the variables listed above, excluding cancellation policy, were utilized as dependent variables. However, variables such as demand (occupancy rate) were used as independent variables, alongside host age and neighborhood.

3.2. Justification for Method Used

Researchers such as Agarwal et al. (2019) [35] have previously utilized Airdna to critique different views of lodging and accommodation platforms, as this dataset allowed them to assess the reliability of variables and their estimates. In another study, Jung et al. (2016) [92] used data from Airdna to compare user behaviors and preferences related to Couchsurfing and Airbnb. Likewise, Gunter (2018) [93] was among the first to apply the Airdna dataset to investigate the process for achieving Superhost status. CBRE Hotel Americas Research (2017) [94] and Kelley and Asad (2015) [95] relied on the same dataset to estimate the effect of Airbnb on hotels. Additionally, Airdna data has been employed by HVS Consulting & Valuation Division of TS Worldwide (2015) [96] in New York City to estimate NYC’s e-hospitality rental marketplace and hotel revenue. Similarly, Dogru and Pekin (2017) [97] utilized the dataset to assess occupancy rate based on guest preference.

3.3. Sample

The purposive sampling technique was used to collect data from the Airdna database between the years 2012 and 2019. The data comprised variables that attest to professionalism, including measures that property consultants have the tendency to improve. The key variables included were Superhost status, overall rating, supply type, price, and reputation. Number of reviews, revenue, property age, maximum guests, minimum stays, photos, incumbent and entrant, bedrooms, and neighborhood were not included.

For the purposes of the study, the following neighborhoods in the Shire of Augusta–Margaret River regional area (Australia) were used: Augusta, Cowaramup, Gracetown, Hamelin-Bay (including Deepdene), Karridale, Margaret River (which consists of Margaret-River city, Rosa Glen, Rosa Brook, Burnside, and Bramley), Molloy-Island, Prevelly, Redgate, Treeton and Witchcliffe.

The motivation for choosing the Shire of Augusta–Margaret River was threefold.

- First, neighborhoods in this sample are some of the most marketed and visited tourist locations within Western Australia.

- Second, the Shire of Augusta–Margaret River has demonstrated increasing interest in supporting ethical and sustainable e-hospitality supply and demand, including inaugurating a parliamentary inquiry to understand more about the dynamics and functionality of the sector in their locality.

- Third, empirical research on e-hospitality in this region is scarce, because most researchers within e-hospitality focus on metropolitan and urban cities at the expense of regions or semi-peripheral urban areas.

Ethics consideration was waived because the dataset was collected from a secondary source, namely Airdna.

4. Results and Findings

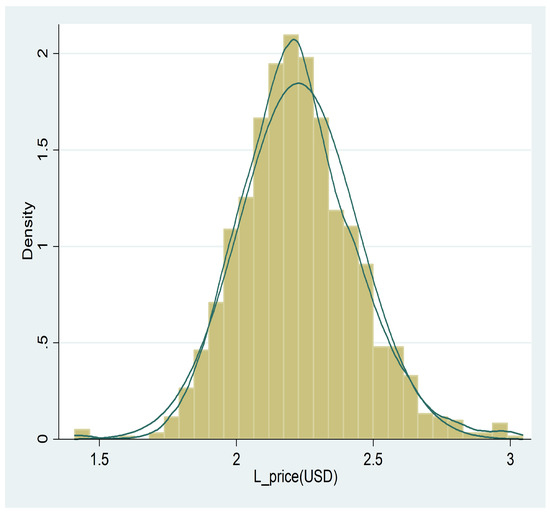

The results from the data collected were first analyzed descriptively to show components such as number of observations, the mean value, and the relationship between variables, including a description of the variable, and description of the skewness of the data (see Table 1). Furthermore, Figure 4, and Table 2 show the results of the normality checks, the test of heteroskedasticity, and the test for multicollinearity of the dataset. Thereafter, the study employed the one-war panel regression which fits within the path analytical framework (see Table 3). To ensure that we explored the data, the hierarchical linear model or nested regression model was used to further assess the relationships (see Table 4).

Figure 4.

Normality Graph.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistical summary of the continuous independent variables. The categorical variable of interest, property manager (p_m) has 1112 observations with other variables in the equation, except for Status_T and Overallrating with 883, and 1012, respectively.

In the 5th column of Table 1, the indicator: description of variables tends to provide both an abbreviation to the indicator been measured, as well as a succinct definition of the variable been measured.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of continuous independent variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of continuous independent variables.

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Description of Variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P_m | 1112 | 0.259 | 0.438 | 0 | 1 | |

| l priceusd | 1112 | 2.226 | 0.216 | 1.41 | 3.045 | ADR = Average daily rate. ADR = Total Revenue/Booked Nights. Includes cleaning fees. |

| supply type | 1112 | 7.458 | 3.398 | 1 | 15 | |

| guest choice | 1112 | 0.486 | 0.234 | 0.032 | 1 | guest choice = Occupancy rate Occupancy Rate = Total Booked Days/(Total Booked Days + Total Available Days). Calculation only includes vacation rentals with at least one Booked Night. |

| l reviews | 1112 | 1.245 | 0.728 | 0 | 2.763 | NOR = Number of Reviews Total number of vacation rental listing reviews |

| revpar | 1112 | 2.069 | 1.047 | 0.081 | 4.765 | |

| overallrating | 1012 | 20.813 | 34.893 | 2 | 100 | OR = Overall Rating Property = Average guest rating of the property out of 5. Ext Property = Average guest rating of the property out of 100 |

| Status T | 883 | 0.458 | 0.498 | 0 | 1 | Status_T = Airbnb Superhost True (1) or False (0) |

| IB T | 1112 | 0.524 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | IB_T = Instantbook feature True (1) or False (0) |

Source: Short-Term Rental Performance for Minnesota and Minnesota Areas, April 2022, https://mn.gov/tourism-industry/assets/AirDNA%20Short-Term%20Rental%20Data%20-%20April%202022%20-%20Industry%20Website_tcm1135-528520.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

Two normality measures were presented for robustness (see Table 2). The result from the Jarque-Bera normality test exhibits Chi(2) 2.27 Chi(2) 0.3 and the Pr(Skewness) 0.26 and Pr(Kurtosis) 0.3 (see Figure 4). The results generated in each instance demonstrate that we cannot therefore reject the null hypothesis of normality, because the data is normal. The results show that the data used in this analysis is not affected by non-normality. Furthermore, with the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test being used to account for heteroskedasticity, the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg result shows chi2(1) = 0.37 and Prob > chi2 = 0.5436. This demonstrates that there is no heteroskedasticity issue with the data. The data is free from heteroskedasticity, and the mean variance inflation factor (VIF) is 1.61.

The results generated for the normality checks, the test of heteroskedasticity, and the multicollinearity results are all within acceptable scores Hair, 1998; Hair, 2006) [98,99].

Table 2 provides the result of the pairwise correlational analysis. The purpose of a correlational matrix is to tabulate the reaction between variables using a two-way method (Štichhauerová, 2010) [100]. Shi, Yang, Zhao, Su, Mao, Zhang & Liu (2017) [101] argues that a correlation coefficient between <0.36 and 0.67 is moderately acceptable, however between 0.68 to 1.0 is high r coefficient. The higher the value to 1, the more it is able to explain the expected variable, hence the weaker the r coefficient the better. Table 2 exhibited adequate appropriateness in data composition for analysis, while Table 2(1) provided clarity on the variable used.

There are different forms of correlational analysis, such as canonical, regression, sparse, partial, bivariate, Spearman and Pearson. The more commonly adopted kinds for the r coefficient are Pearson, regression, and Spearman. Thus, when a pairwise r matrix allowing the significance of the data pull to be tested was conducted, the Pearson r coefficient was adopted.

Table 2.

Pairwise correlations matrix.

Table 2.

Pairwise correlations matrix.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) p_m | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (2) l_priceusd | 0.098 * | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (0.001) | ||||||||||

| (3) supply_type | 0.013 | 0.208 * | 1.000 | |||||||

| (0.670) | (0.000) | |||||||||

| (4) guest_choice | −0.036 | −0.309 * | −0.062 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (0.232) | (0.000) | (0.037) | ||||||||

| (5) overallrating | 0.471 * | 0.149 * | 0.060 | −0.185 * | 1.000 | |||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.055) | (0.000) | |||||||

| (6) l_reviews | −0.596 * | 0.151 * | 0.087 * | −0.155 * | −0.034 | 1.000 | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.004) | (0.000) | (0.279) | ||||||

| (7) revpar | −0.297 * | 0.089 * | 0.074 | −0.066 | −0.008 | 0.486 * | 1.000 | |||

| (0.000) | (0.003) | (0.013) | (0.027) | (0.788) | (0.000) | |||||

| (8) Status_T | −0.071 | −0.196 * | −0.027 | 0.301 * | 0.242 * | −0.040 | −0.046 | 1.000 | ||

| (0.034) | (0.000) | (0.424) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.231) | (0.170) | ||||

| (9) IB_dum_T | −0.185 * | −0.149 * | −0.076 | 0.097 * | −0.128 * | 0.100 * | 0.035 | 0.011 | 1.000 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.012) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.245) | (0.741) | |||

| (1) Variable Description | ||||||||||

| Concept | Meaning | In-Text Reference | ||||||||

| Overall rating | A numerical value based on guests’ experiences and satisfaction with their stay. It takes into account various aspects such as cleanliness, accuracy of the listing, communication with the host, and location. | (Guttentag, 2015) [29] | ||||||||

| Daily price | The amount of money charged by the host per night for their rental property. It can vary depending on factors such as location, amenities, and time of year. | (Zervas et al., 2017) [102] | ||||||||

| RevPAR | Revenue per available room, a performance metric used in the hotel industry to measure the total revenue earned per room available for occupancy. In the context of short-term rentals, it can be calculated as the product of the average daily rate and the occupancy rate. | (Guttentag, 2015) [29] | ||||||||

| Supply type | The type of rental property available for guests, such as entire homes/apartments, private rooms, or shared rooms. It can impact guests’ preferences and the overall performance of the rental property. | (Zervas et al., 2017) [102] | ||||||||

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

The bivariate Pearson correlation coefficient is incongruent with the hypothesized proposition. For instance, property manager/management positively correlates with price (γ = 0.098, p < 0.001) and overall rating (γ = 0.471, p < 0.00001), while reviews (γ = −0.596, p < 0.00001), RevPAR (γ = −0.297, p < 0.00001), and Instantbook feature (γ = −0.185, p < 0.00001) at 0.01% interval were negatively correlated.

Panel Analysis or Linear Regression

Panel analysis or linear regression is a statistical methodology that is widely adopted in social science, econometrics, finance and banking, and epidemiology to analyze two-dimensional panel data. Much of the data used is readily collected over time and over a given sample, and then a regression is run over the two dimensions. Table 3 provides the linear regression demonstrating the directionality and correlationality of the data, as well as checking the estimates for model fit, including the usefulness of the model guaranteeing an evaluation of reliability and validity of the dataset. Table 3 indicates a positive and significant path from property manager/management company to price (β1 = 0.24, p < 0.0001), reviews (β1 = −0.318, p < 0.0001), Superhost status (β1 = −0.46, p < 0.03), and utilization of the Instantbook feature (β1 = −0.45, p < 0.03). Thus, professionals managing e-hospitality infrastructure assist in estimating price points, achieving Superhost status, and in gaining more positive reviews on Stayz. Nonetheless, the result shows that property manager or management firm does not appear to influence a guest’s choice to stay in an apartment and does not influence overall ratings of the property managed.

Table 3.

Linear regression.

Table 3.

Linear regression.

| p_m | Coef. | St. err. | t-Value | p-Value | [95% Conf Interval] | Sig | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l_priceusd | 0.244 | 0.055 | 4.48 | 0 | 0.137 | 0.351 | *** | ||||

| supply_type | 0 | 0.003 | −0.03 | 0.976 | −0.006 | 0.006 | |||||

| guest_choice | 0.012 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.811 | −0.086 | 0.11 | |||||

| l_reviews | −0.318 | 0.016 | −19.83 | 0 | −0.35 | −0.287 | *** | ||||

| revpar | −0.002 | 0.011 | −0.20 | 0.838 | −0.024 | 0.019 | |||||

| overallrating | −0.003 | 0.043 | −0.07 | 0.948 | −0.087 | 0.081 | |||||

| Status_T | −0.046 | 0.022 | −2.14 | 0.033 | −0.089 | −0.004 | ** | ||||

| IB_dum_T | −0.045 | 0.021 | −2.18 | 0.03 | −0.086 | −0.004 | ** | ||||

| Constant | 0.078 | 0.244 | 0.32 | 0.749 | −0.4 | 0.556 | |||||

| Mean dependent var | 0.167 | SD dependent var | 0.373 | ||||||||

| R-squared | 0.393 | Number of obs | 832 | ||||||||

| F-test | 66.673 | Prob > F | 0.000 | ||||||||

| Akaike crit. (AIC) | 322.588 | Bayesian crit. (BIC) | 365.103 | ||||||||

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10.

The result here supports the notion that property managers and management firms can assist in improving the value and price point of an owner’s property, and also that reputation in terms of reviews can be reinforced by these consultants, although this may not necessarily lead to an increase in overall ratings. Other research shows that both reviews and overall ratings constitute reputational management variables, however. Ndaguba (2023) [1] shows that Superhost status also adds to the reputational management variable; hence reviews, overall ratings, and Superhost status go together to make up the reputational management variable, and since the three variables measure the same value, one or two of them may be considered for analysis. In Table 4, we omitted reviews and Superhost status to avoid issues of multicollinearity. Also, guest choice (occupancy rate) was omitted, as it coincided with RevPAR, with RevPAR being estimated by revenue/occupancy rate.

To further expand on Table 3, due to the simplicity of the path/panel model, hierarchical linear regression was employed to expand the horizon of the result. The essence is predicated based on hierarchical linear estimation, which is to monitor the reaction of variables as new or more variables are loaded onto the estimation model. The model is considered important because it makes multiple linear regression analyses possible. Table 4 sets out five proposed empirical models, while Table 5 provided the summary of hypothesis tested and its outcomes.

Table 4.

Direct and indirect model specification.

Table 4.

Direct and indirect model specification.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | p_m | p_m | p_m | Overallrating | Supply_Type |

| overallrating | 0.00590 *** | 0.00591 *** | |||

| (0.000355) | (0.000355) | ||||

| l_priceusd | 0.0599 | 0.254 *** | 0.0701 | 23.65 *** | 3.498 *** |

| (0.0588) | (0.0579) | (0.0600) | (5.266) | (0.496) | |

| revpar | −0.129 *** | ||||

| (0.0119) | |||||

| supply_type | −0.00296 | 0.301 | |||

| (0.00368) | (0.326) | ||||

| Constant | 0.00919 | −0.0392 | 0.00862 | −33.81 *** | −0.290 |

| (0.130) | (0.130) | (0.130) | (11.44) | (1.104) | |

| Observations | 1.012 | 1.112 | 1.012 | 1.012 | 1.112 |

| R-squared | 0.223 | 0.104 | 0.223 | 0.023 | 0.043 |

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Mean VIF | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.00 |

Standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10.

Table 5.

Summary of hypotheses forecast.

Table 5.

Summary of hypotheses forecast.

| Hypotheses | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Supported |

| Supported |

| Not Supported |

| Supported |

Model 1 presents the proposition that property manager/management firm has a positive influence on overall rating but shows no association with price. This finding is unusual, as Sigala (2019) [103], and Zervas, Proserpio and Byers (2017) [102] had earlier provided evidence to suggest that property managers can have a positive influence on the daily price of Airbnb properties. Our study shows that when property manager is nested with ratings and daily price, daily price becomes mute. The result in Table 4, Model 1 shows that there is a significant and positive relationship property management → overall ratings (β1 = 0.01, p < 0.001), but fails to account for any relationship with price. However, in Model 2, which proposes the relationship property manager/management firm → price → RevPAR, both nested values became significant, with price having a position association (β1 = 0.254, p < 0.01), while RevPAR was negative and significant (β1 = −0.129, p < 0.01).

About model 3 property manager/management firm → overall rating → price → supply type, the result demonstrates that property manager and ratings were significant and positively supported. However, the relationship between price and supply type did not turn out to be significant. The postulation in Model 4 for overall rating → price → supply type suggests that overall rating when weighted on price (β2 = −23.65, p < 0.01) and supply types exhibited that overall rating has a significantly positive relationship with price, but the ratings have no bearing on supply type. Upon assessment of Model 5, it was found that a 1% increase in the supply of homes corresponds to a 3.498% increase in prices. This aligns with the findings of Franco and Santos (2021) [104], who suggest that a 1% growth in supply results in a price increase for rent.

5. Discussion

The short-term rental industry has become increasingly popular in recent years, with the rise of online platforms like Airbnb and VRBO. However, the industry has also faced criticism for its potential negative impacts on local communities and the environment. To promote sustainable growth in this industry, it is important to understand the complex relationships between various variables.

One study conducted by Curran and Bauer (2011) [105] used hierarchical linear modelling (HLM) to examine these relationships while accounting for the nested structure of the data. The findings of this study emphasized the complex nature of these relationships, highlighting the need for a comprehensive approach to promoting sustainable growth in the industry.

The result of this study indicates that property managers and management firms can promote sustainable growth through their reputational and managerial influences. However, the relationship between these variables (property managers and overall ratings) on supply type was not significant. This suggests that property managers and management firms do not have the ability to create more supplies, as that is purely the prerogative of the investors and policymakers. Similarly, the study demonstrates that areas where properties ratings are very high does not translate to an increase in supplies. These findings are critical for sustainability development in the short-stay sector, as they indicate that the powers of managers and management firms are limited. Hence, laws guiding the activities of property managers and management firms should be laws of a third party.

The use of statistical analyses such as β1 and β2 coefficients can provide a nuanced understanding of the relationships between variables. Baron and Kenny (1986) [106] proposed the use of β1 coefficients for the relationship between independent and mediator variables and β2 coefficients for the association between the independent variable mediator and the dependent variable. The finding that overall rating mediates the relationship between property manager/management firm and price highlights the importance of guest experiences in determining the revenue accruing to short-term vendors.

In conclusion, promoting sustainable growth in the short-term rental industry requires a comprehensive approach that considers the interplay between variables. The use of HLM and statistical analyses such as β1 and β2 coefficients can provide valuable insights into these relationships and inform strategies for promoting sustainable growth (Curran & Bauer, 2011; Baron & Kenny, 1986) [105,106]. These findings have important implications for the development of policies and regulations that can help to mitigate the negative impacts of the short-term rental industry on local communities and the environment. By understanding the complex relationships between variables, we can develop more effective strategies for promoting sustainable growth in this industry.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

For the study a dataset from Airdna for HomeAway, also popularly known as Stayz, was utilized as a representative sample from a tourism town in Western Australia to empirically examine four hypothesized values for the sharing economy within e-hospitality to arrive at an understanding or estimate of the place of property managers or property management roles in three categories: price determinant, reputational attribute, and supply types in the e-hospitality sector in a semi-urban destination town. Afterwards, the nature of supply (supply type), such as private room and entire home was assessed against price, while a reputational variable, such as overall rating was estimated also on price. The study provides opportunities for theoretical connotation, as explained next.

First, property managers or management firms help in improving the overall reputation of and trust in a property in the e-hospitality sector. A good reputation not only assists in improving revenues in the e-hospitality sector, but also helps to improve recommendation among friends, colleagues, and family members. Schuckert, Liu, and Law (2015) [107] argue that complimentary reviews are vital for the general wellbeing and sustainability of digital platforms, although the overall rating is of great concern to hotel and restaurant pricing, as well as the overall sales in both hotels and restaurants. In the same vein, high ratings, which is an attribute of the property manager or management firm, can generate a level of price premium in the e-hospitality sector. Also, findings Öğüt and Onur Taş (2012) [108] suggested that higher ratings increase sales, and that an increase of 1% in overall rating had a 2.6% increase effect on hotel room sales, which the sharing platforms can replicate. This demonstrates that professionalism in the sharing economy is vital for advancing the e-hospitality sector. It further demonstrates that while property managers or management firms assist in raising the overall ratings of a property, the reputation and trust based on the reviews and overall rating of the property increase the chance of improved throughput in the e-hospitality sector. Research further shows that 94% of negative reviews led to poor ratings, because of which prospective guests avoided booking a property. Hence, to ensure that a property does not get bad or negative reviews, which would have a negative effect on the rating of the property, professionals in the management of properties are important (Kim & Lee, 2020) [109].

Second, property managers or management firms assist in improving the revenue per available room (RevPAR) in the e-hospitality sector. Very little research has been conducted to assess whether professionalism in the context of sharing platforms improves RevPAR in the e-hospitality sector. Our study was therefore conducted with the aim of adding to the body of theoretical literature on sharing platforms and to establish a foundation on which other literature can build. The use of a property manager or management firm thus causes both price and RevPAR to rise due to professionalism in the sharing platform. A third contribution relates to the fact that price differentials are evident when there are more supply types.

This proves that the sharing economy has brought significant changes to traditional industries, but also that it faces obstacles in terms of professionalism. Several studies have identified ways to professionalize the sharing economy, including:

- Developing clear regulations: Regulations are essential to promoting professionalism and trust in the sharing economy. Kim and Lee (2019) [109] suggests that governments should work with sharing economy platforms to develop clear regulations that promote transparency and consumer protection.

- Implementing quality control measures: Quality control measures can help ensure that goods and services provided on sharing economy platforms meet certain standards. For example, to maintain their listing on the platform, Airbnb requires hosts to meet certain criteria, including providing a clean and safe space for guests (Guttentag, 2015) [29].

- Enhancing communication and transparency: Effective communication and transparency can help build trust and credibility in the sharing economy. A study by Sundararajan (2017) [110] suggests that sharing economy platforms should provide users with clear information on pricing, quality, and availability.

- Improving reputation systems: Reputation systems can help build trust among users in the sharing economy. As discussed earlier, several studies have explored ways to improve reputation systems, such as detecting fraudulent ratings and encouraging honest reviews (Hamari et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2020) [111,112].

Overall, professionalizing the sharing economy requires a multifaceted approach that involves developing clear regulations, implementing quality control measures, enhancing communication and transparency, and improving reputation systems. These measures can help promote trust and credibility among users and ensure that the sharing economy continues to grow and evolve in a professional manner.

5.2. Management Implications

The e-hospitality enterprise belongs within the philosophy of the sharing economy (Belk, 2007) [31], which is a recognized and critical player around economic regenerative wealth and development. Scholars such as Schor and Attwood-Charles (2017) [113] perceive it to be a poverty reduction and survival mechanism for most developing countries. Nonetheless, issues such as concept ambiguity, uncharted territory, unclear boundaries, and regulations are factors creating superficial layers derailing the composition and the conceptualization of professionals within the sharing economy discourse. The research on which our study was based showed models of e-hospitality, namely ticket clippers and end-to-end models, to be in competition.

For instance, owners/hosts provide booking channels through which owners grant guests access to their apartments. Agents and agencies play similar roles but rely on the end-to-end model rather than merely being a booking channel. Hence, there are two models in competition for guests, namely the booking channel or ticket clipper model, and the end-to-end model.

Booking channels refer to those organizations who provide one-way e-hospitality traction in the accommodation business, for instance through providing ticketing or organizing booking at a fee, usually capped at between 12% and 18%. Booking channels in fact constitute an intermediary between the homeowners/hotels, B&Bs and the guests. Examples of those that have adopted the ticket clipper model are owners or individuals who rely on Airbnb, TripAdvisor, Booking.com and Stayz to gain traction for their accommodation, without providing further services to the guest until they are locked into their contract to stay, and access is granted. The end-to-end model provides a closer relationship with guests. End-to-end providers are firms or agencies that concern themselves with the entire ecosystem of the sharing economy in the e-hospitality sector. They provide marketing services for the accommodation, booking services, cleaning services, laundry services, and the general maintenance and care of the property, with a 20% cap. Furthermore, they often introduce the new occupant to their neighbors, in that way engendering a cordial relationship between the guest and their neighbors.

Some of the more popular end-to-end providers or management firms in the Margaret River region are Exclusive Escapes, Seaside Escapes and managers/agents who oversee several properties on behalf of rentvestors and investors fees are usually capped at 20%, while ticket clippers charges between 13–18%.

Exclusive Escapes and Seaside Escapes are for medium- and high-earn rentals; as a result, there is a dearth of professionalism in the lower strata of the e-hospitality market. Most end-to-end providers (management firms) are registered, and their employees are 100% local, and they are heavily taxed compared with the booking channels. This does not take anything away from the ticket clippers, but from our observations one of the main concerns relating to the booking channel model is the high prevalence of non-registered providers, and tax evasion due to non-accountability.

E-hospitality offers a myriad of opportunities to communities and hosts in tourism-related destinations. This may lead to the expansion of destination areas, which could bring about significant government investment based on tourist spending. It also assists hotels and other traditional e-hospitality enterprises in providing an augmented lodging capacity, particularly during school holidays and other peak seasons, and assists in reducing accommodation prices (Hajibaba & Dolnicar, 2017) [114].

6. Conclusions

The study was conducted for the purpose of assessing the contribution of professionalism in engendering the sustainable growth of the e-hospitality sector. The research demonstrated that professionals are active throughout the ecosystem of the sharing economy from pickup to welcoming, booking services, cleaning services, laundry services, introduction to neighbors, advertising, and the general maintenance and care of the property. Furthermore, professionals tend to recruit entirely from their immediate environment. It was observed that they are heavily taxed as compared with ticket clippers.

Findings from the research indicate that professionals improve the reputation of a property and assist in the management of the reputation of the property over an extended period, as evidenced by the fact that properties managed by property managers tend to be awarded Superhost status, attract a rise in overall ratings, and receive increased numbers of positive reviews. Furthermore, the relationship among property managers, daily prices, and RevPAR shows a significant positive trend in that hosts who make use of property managers or management firms are able to command a 20% higher daily price, despite a 10% decline in RevPAR.

The contribution of the study reported on is threefold. First, it proposed two models for understanding e-hospitality, namely the ticket clipper and end-to-end models. It went further to demonstrate which one was sustainable and why the other is not capable of ensuring sustainable growth for hosts and property managers. The second contribution relates to the tenets of professionalism in e-hospitality, and how property managers or management firms can assist in establishing a cordial relationship between visitors and neighbors. The third refers to the ways in which property managers or management firms can improve the image, reputation, and financial benefits of homeowners’ properties.

The adoption of professional ethics is essential to the sustainability of growth in the e-hospitality sector, and in advancing the image, finance, and reputation of home use in the e-hospitality network. Thus, the end-to-end model is perhaps the single most important proposition for the professionalization of the sharing economy. Ticket clippers and unregistered hosts will always exist, but the government has the responsibility for reducing illegal and unregulated participants in the e-hospitality ecosystem while ensuring that the registered ticket clippers are not overshadowed by bigger firms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.N.; methodology, E.N.; software, E.N.; validation, C.V.Z. and E.N.; formal analysis, E.N. and C.V.Z.; investigation, E.N. and C.V.Z.; resources, E.N.; data curation, E.N. and C.V.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, E.N.; writing—review and editing, E.N. and C.V.Z.; visualization, E.N.; supervision, C.V.Z.; project administration, E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

No human or animal consent required, since it is third party.

Data Availability Statement

www.airdna.co, 25 February 2021.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the proofreading support by Sheldon Heeg, Janey, University of South Africa.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflict of interest.

References

- Ndaguba, E.A. Social and Economic Impact of Short-Stay Accommodation. Ph.D. Thesis, Edith Cowan Library Service, Joondalup, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Coghlan, A.; Jin, X. Understanding the drivers of Airbnb discontinuance. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 80, 102798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki, A.; Dacko, A.; Dacko, M. Changes in mobility patterns and the switching roles of second homes as a result of the first wave of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 31, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Mackenzie, S.H.; Degarege, G.A. Airbnb impacts on host communities in a tourism destination: An exploratory study of stakeholder perspectives in Queenstown, New Zealand. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 30, 1122–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; He, S.; Wan, C. Unraveling the dynamic Airbnb-gentrification interrelation before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Beijing, China. Cities 2023, 137, 104270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeqiri, A.; Dahmani, M.; Yousse, A. Determinants of the use of e-services in the hospitality industry in Kosovo. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2021, 5, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M.; Rahimi, R.; Thelwall, M. Big Data and Innovation in Tourism, Travel, and Hospitality. Available online: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789811363382 (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Choi, S.-H.; Lee, H. Workplace violence against nurses in Korea and its impact on professional quality of life and turnover intention. J. Nurs. Manag. 2017, 25, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, F.; Costa, C.; Buhalis, D. Tourism innovation networks: A regional approach. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 18, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. Understanding Key Antecedents of Consumer Loyalty toward Sharing-Economy Platforms: The Case of Airbnb. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyall, A.; Legoherel, P.; Poutier, E. (Eds.) Revenue Management for Hospitality and Tourism; Goodfellow Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, C.; Guttentag, D.; Gretzel, U.; Yao, L.; Morton, J. Use of dynamic pricing strategies by Airbnb hosts. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.; Miles, L. Reputation Management: Theory versus Practice. Corp. Reput. Rev. 1998, 2, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, A. The Reputation Economy: Understanding Knowledge Work in Digital Society; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Luca, M.; Svirsky, D. Detecting and Mitigating Discrimination in Online Platforms: Lessons from Airbnb, Uber, and Others. NIM Mark. Intell. Rev. 2020, 12, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalicic, L.; Marine-Roig, E.; Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Martin-Fuentes, E. Destination image analytics for tourism design: An approach through Airbnb reviews. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 86, 103100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Agag, G.; El-Masry, A.A. Why Do Consumers Trust Online Travel Websites? Drivers and Outcomes of Consumer Trust toward Online Travel Websites. J. Travel Res. 2016, 56, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitidis, P.; Economou, A.; Grigoriou, G.; Kollias, C. Trust in peers or in the institution? A decomposition analysis of Airbnb listings’ pricing. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 25, 3500–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicchieri, C.; Duffy, J.; Tolle, G. Trust among Strangers. Philos. Sci. 2004, 71, 286–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ert, E.; Fleischer, A. What do Airbnb hosts reveal by posting photographs online and how does it affect their perceived trustworthiness? Psychol. Mark. 2019, 37, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deboosere, R.; Kerrigan, D.J.; Wachsmuth, D.; El-Geneidy, A. Location, location and professionalization: A multilevel hedonic analysis of Airbnb listing prices and revenue. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2019, 6, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casamatta, G.; Giannoni, S.; Brunstein, D.; Jouve, J. Host type and pricing on Airbnb: Seasonality and perceived market power. Tour. Manag. 2021, 88, 104433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurran, N.; Phibbs, P. When Tourists Move In: How Should Urban Planners Respond to Airbnb? J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2017, 83, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Moreno, A.; Zhang, D. Pros vs Joes: Agent Pricing Behavior in the Sharing Economy (28 August 2016). Ross School of Business Paper No. 1298. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2708279 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Oskam, J.; van der Rest, J.-P.; Telkamp, B. What’s mine is yours—But at what price? Dynamic pricing behavior as an indicator of Airbnb host professionalization. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2018, 17, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, S. Professionalism. S. Afr. Dent. J. 2016, 71, 180. [Google Scholar]

- Botsman, R. The Sharing Economy Lacks a Shared Definition; Fast Company: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Guttentag, D. Airbnb: Disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1192–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.J.; Upham, P. Grassroots social innovation and the mobilisation of values in collaborative consumption: A conceptual model. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Why not share rather than own? Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2007, 611, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, C. Mapping Airbnb supply in European cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 71, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, L.; Dudás, G.; Kovalcsik, T.; Papp, S.; Vida, G. Airbnb in Budapest: Analysing spatial patterns and room of hotels and peer-to-peer accomodations. GeoJournal Tour. Geosites 2018, 10, 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dogru, T.; Mody, M.; Line, N.; Suess, C.; Hanks, L.; Bonn, M. Investigating the whole picture: Comparing the effects of Airbnb supply and hotel supply on hotel performance across the United States. Tour. Manag. 2020, 79, 104094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, V.; Koch, J.V.; McNab, R.M. Differing Views of Lodging Reality: Airdna, STR, and Airbnb. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2018, 60, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckle, S.; Bhattacharya, R.; White, M.; Beloff, N. Internet of Things, Blockchain and Shared Economy Applications. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 98, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberger, B.Z. Redefining employee in the gig economy: Shielding workers from the Uber model Fordham. J. Corp. Fin. L. 2017, 23, 577. [Google Scholar]

- Udehn, L. Twenty-five Years with The Logic of Collective Action. Acta Sociol. 1993, 36, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours. The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Collins: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rinne, A. A Big Trends for the Sharing Economy in 2019. 2019. Available online: www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/sharing-economy (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption Is Changing the Way We Live; Collins: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zentner, A. Measuring the Effect of File Sharing on Music Purchases. J. Law Econ. 2006, 49, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M.; Raynor, M.; Mcdonald, R. The Big Idea: What is disruptive innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 93, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zeleny, M. Linear Multiobjective Programming; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 95. [Google Scholar]

- Pattinson, H.M.; Woodside, A.G. Capturing and (re) interpreting complexity in multi-firm disruptive product innovations. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2008, 24, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Imarah, A.A.; Shields, R. MOOCs, disruptive innovation and the future of higher education: A conceptual analysis. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2018, 56, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, V.; Souto-Manning, M.; Turvey, K. Innovation in teacher education: Towards a critical re-examination. J. Educ. Teach. 2018, 45, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]