An Integrated Mediating and Moderating Model to Improve Service Quality through Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment

Abstract

1. Introduction

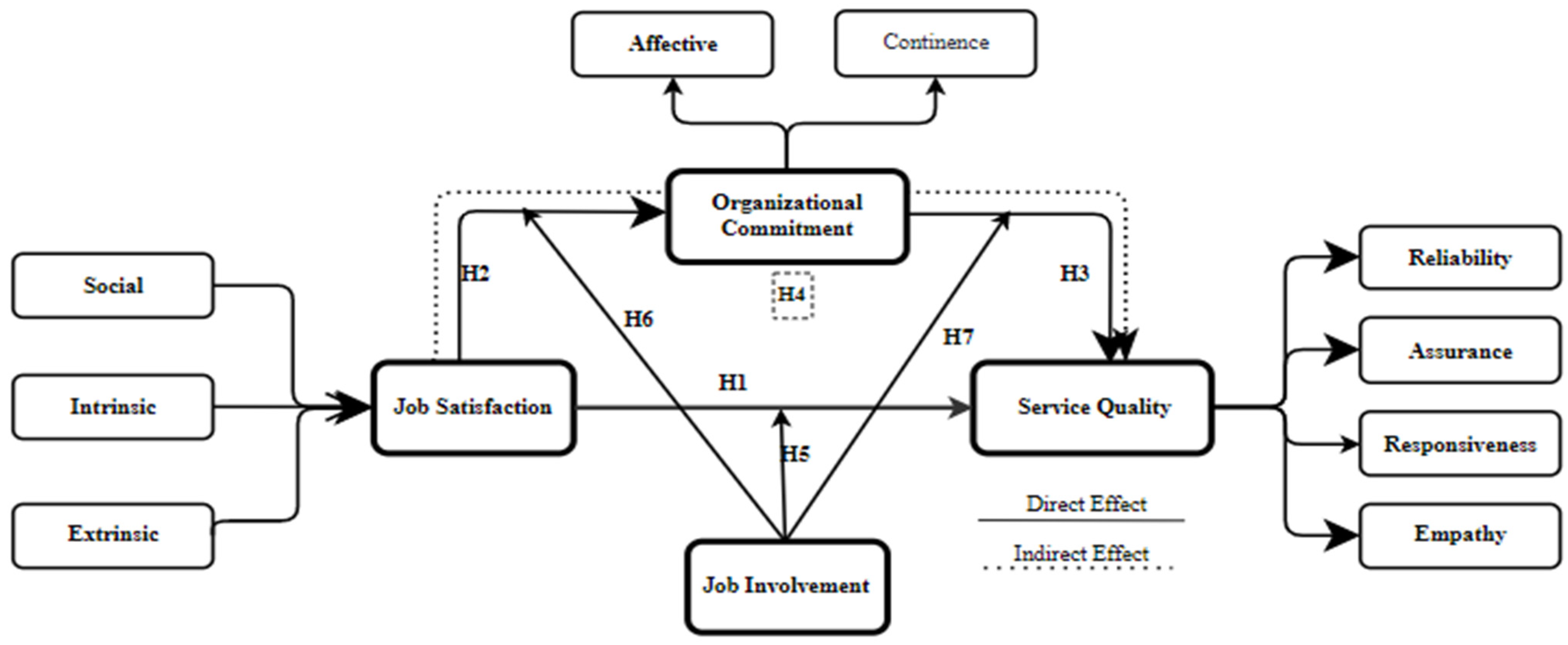

2. Theoretical Underpinnings and Hypothesis Development

2.1. JS and SQ

2.2. JS and OC

2.3. OC and SQ

2.4. Job Involvement as a Moderator

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Job Satisfaction

3.2.2. Organizational Commitment

3.2.3. Job Involvement

3.2.4. Service Quality

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Inputs

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profile of Respondents

4.1.1. Lecturer Profile

4.1.2. Students Profile

4.2. Normality and Multicollinearity

4.3. Assessment of Measurement Model

4.4. Structural Model Results and Testing of the Hypotheses

4.4.1. Result of the Direct Hypotheses

4.4.2. Result of the Indirect Effect (Mediating Effect)

Proportion of Mediation

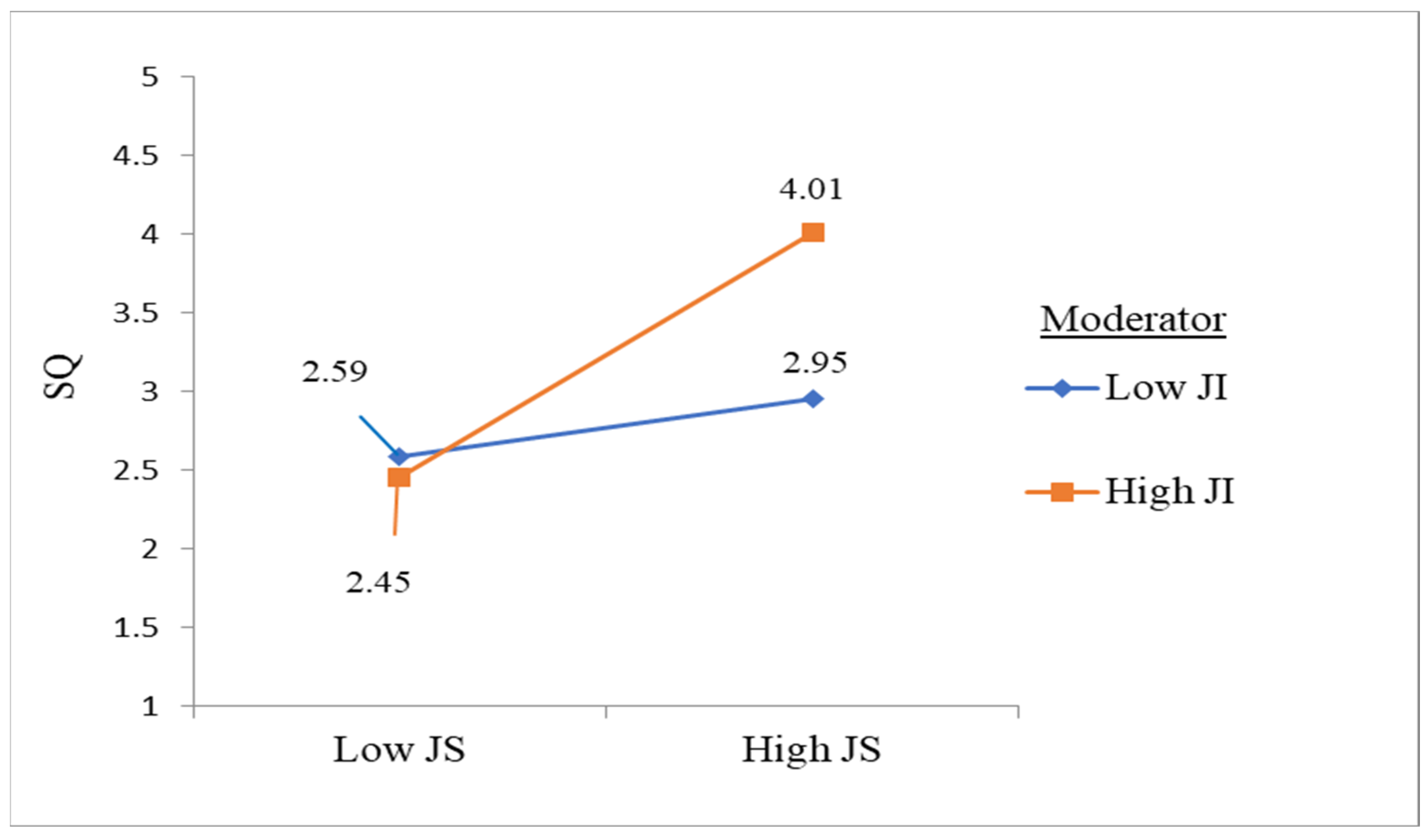

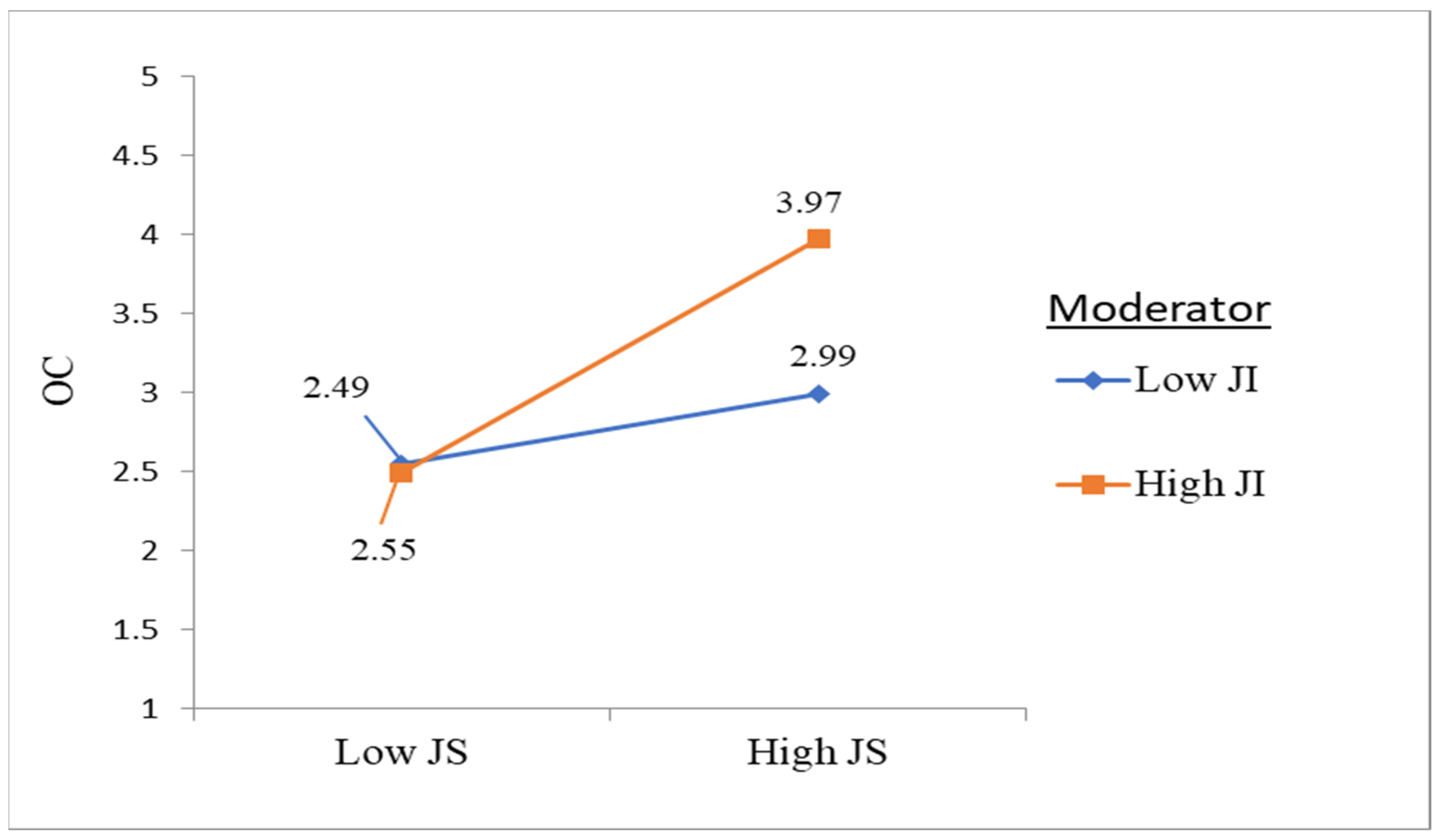

4.5. Moderating Impacts of Job Involvement: Two-Way Interaction

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Contribution

5.2. Practical Implication

6. Limitations and Direction for Further Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demirel, D. The Effect of Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction in Digital Age: Customer Satisfaction Based Examination of Digital Crm. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2022, 23, 507–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivellas, P.; Dargenidou, D. Organisational culture, job satisfaction and higher education service quality. TQM J. 2009, 21, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseer, A.; Shahzad, K. Internal marketing, job satisfaction and service quality: A study of higher education institutions of Pakistan. Dialogue 2016, 11, 402–414. [Google Scholar]

- Al-refaei, A.A.-A. The Relationship Between HRM Practices and Service Quality in Higher Education in Yemen: Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction and Job Involvement as Mediating Variables. Doctoral Dissertation, Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, Nilai, Malaysia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Küskü, F. Employee satisfaction in higher education: The case of academic and administrative staff in Turkey. Career Dev. Int. 2003, 8, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-refaei, A.A.-A.; Zumrah, A.R.; Alsamawi, M.; Alshuhumi, S. A Multi-Group Analysis of the Effect of Organizational Commitment on Higher Education Services Quality. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2019, 3, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.; Khalifa, B. What forms university? An integrated model from Syria. Bus. Theory Pract. 2016, 17, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A.; Zelthami, V.A. The Service-Quality Puzzle.pdf. Bus. Horiz. 1988, 31, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.; Mukherjee, A. The relative influence of organisational commitment and job satisfaction on service quality of customer-contact employees in banking call centres. J. Serv. Mark. 2004, 18, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, a. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. Service Quality, Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty: The Moderating Role of Gender/Aptarnavimo KokybĖ, VartotojŲ Pasitenkinimas Ir Lojalumas VartotojŲ Lyties AtŽvilgiu. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2011, 12, 278–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalini, R.; Amudha, R.; Sujatha, V.; Radha, R. A Pragmatic Study on the Service Gap Analysis of an Indian Public Sector Bank. Bus. Theory Pract. 2014, 15, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pourcq, K.; Verleye, K.; Lariviere, B.; Trybou, J.; Gemmel, P. Implications of customer participation in outsourcing non-core services to third parties. J. Serv. Manag. 2021, 32, 438–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, M.; Yuan, X. Managing Price and Service Rate in Customer-Intensive Services under Social Interactions. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 20, 878–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babakus, E.; Yavas, U.; Karatepe, O.M.; Avci, T. The Effect of Management Commitment to Service Quality on Employees’ Affective and Performance Outcomes. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2003, 31, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Avci, T.; Arasli, H. Effects of Job Standardization and Job Satisfaction on Service Quality: A Study of Frontline Employeesin Northern Cyprus. Serv. Mark. Q. 2004, 25, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivellas, P.; Santouridis, I. Job satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between service quality and organisational commitment in higher education. An empirical study of faculty and administration staff. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2016, 27, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumrah, A. Training, Job Satisfaction, POS and Service Quality: The Case of Malaysia. World J. Manag. 2015, 6, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, R.W.Y.; Guo, Y.; Yeung, A.C.L. Being close or being happy? The relative impact of work relationship and job satisfaction on service quality. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 169, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariani, D.W. Employee satisfaction and service quality: Is there relations. Int. J. Bus. Res. Manag. 2015, 6, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzoli, G.; Hancer, M.; Park, Y. The role and effect of job satisfaction and empowerment on customers’ perception of service quality: A study in the restaurant industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 34, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-refaei, A.a.-a.; Zumrah, A.R. The Effect of Affective Commitment of Non-Academic Staff on Services Quality in Higher Education Sector. In Proceedings of the 5th World Conference on Integration of Knowledge 2019, Bangi Selangor, Malaysia, 29 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Chuang, A. A multilevel investigation of factors influencing employee service performance and customer outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaibani, E.; Bakir, A. A reading in cross-cultural service encounter: Exploring the relationship between cultural intelligence, employee performance and service quality. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Toya, K.; Lepak, D.P.; Hong, Y. Do they see eye to eye? Management and employee perspectives of high-performance work systems and influence processes on service quality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, M.N.; Xiuchun, B.; Abbas, J.; Shuguang, Z. Analyzing predictors of customer satisfaction and assessment of retail banking problems in Pakistan. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1338842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould-Williams, J.; Davies, F. Using social exchange theory to predict the effects of HRM practice on employee outcomes: An analysis of public sector workers. Public Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culibrk, J.; Delic, M.; Mitrovic, S.; Culibrk, D. Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Job Involvement: The Mediating Role of Job Involvement. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.G.; Qureshi, H.; Frank, J. The good life: Exploring the effects job stress, job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment on the life satisfaction of police officers. Int. J. Police Sci. Manag. 2021, 23, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiharjo, R.J.; Purbasari, R.N.; Parashakti, R.D.; Prastia, A. The Effect of Job Involvement, Organizational Commitment, and Job Satisfaction on Turnover Intention. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 11, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, J.; Zajac, D. A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, V.; Singh, S.K. Moderation Effect of Job Involvement on the Relationship Between Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beheshtifar, M.; Emambakhsh, M. Relation between Job Involvement and Service Quality. Appl. Math. Eng. Manag. Technol. 2015, 1, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Al-refaei; Zumrah, A.R.; Alshuhumi, S.R. The Effect of Organizational Commitment on Higher Education Services Quality. In E-Journal on Integration of Knowledge, 7th ed.; 2019; pp. 8–16. Available online: https://worldconferences.net (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Morrow, P.C. Concept Redundancy in Organizational Research: The Case of Work Commitment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1983, 8, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegge, J.; Schmidt, K.-H.; Parkes, C.; Dick, R. Taking a sickie: Job satisfaction and job involvement as interactive predictors of absenteeism in a public organization. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 80, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, G.J.; Boal, K.B. Conceptualizing how job involvement and organizational commitment affect turnover and absenteeism. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnake, M.E. an Empirical Assessment of the Effects of Affective Response in the Measurement of Organizational Climate. Pers. Psychol. 1983, 36, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, T.R.; Porter, W.L.; Steers, R.M. Employee—Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B.; Parkington, J.; Buxton, V. Employee and Costumer Perceptions of Service in Banks. Adm. Sci. Q. 1980, 25, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micah, A.E.; Bhangdia, K.; Cogswell, I.E.; Lasher, D.; Lidral-Porter, B.; Maddison, E.R.; Nguyen, T.N.N.; Patel, N.; Pedroza, P.; Solorio, J. Global investments in pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: Development assistance and domestic spending on health between 1990 and 2026. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e385–e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberger, R.; Fasolo, P.; Davis-LaMastro, V. Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumrah, A.R.B.; Bahaj, M.H.A.; Alrefai, A.S. An Empirical Investigation of the Effect of Training and Development on Organizational Commitment in Higher Education Sector. J. Int. Bus. Manag. 2021, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964; p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Ukil, M.I. The Impact of Employee Empowerment on Employee Satisfaction and Service Quality: Empirical Evidence from Financial Enterprizes in Bangladesh. Verslas Teor. Ir Prakt. 2016, 17, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finanda, Y.D.; Lutfi. The Influence of Employee Job Satisfaction and Service Quality on Profitability in Pt. Bank Jatim: Customer Satisfaction as the Intervening Variable. Russ. J. Agric. Socio-Econ. Sci. 2018, 74, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Tang, C. How does training improve customer service quality? The roles of transfer of training and job satisfaction. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.R.; Saha, J.; Alam, M.M.D. The Impact of Service Climate and Job Satisfaction on Service Quality in a Higher Education Platform. Int. J. Learn. Dev. 2017, 7, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Evaluating service quality and performance of higher education institutions: A systematic review and a post-COVID-19 outlook. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2021, 13, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogdu, S.; Asikgil, B. An Empirical Study of the Relationship Among Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intention. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2011, 1, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tett, R.P.; Meyer, J.P. Job Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, Turnover Intention, and Turnover: Path Analyses Based on Meta-Analytic Findings. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 259–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R.J.; Lance, C.E. Examining the Causal Order of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. J. Manag. 1992, 18, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, S. Structural determinants of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in turnover models. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1999, 9, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, S.M. Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment among Employees in the Sultanate of Oman. Psychology 2010, 1, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Deshpande, S.P. The Impact of Caring Climate, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment on Job Performance of Employees in a China’s Insurance Company. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suderajat, S.; Rojuaniah, R. The Effect Of Teacher Profesional Allowance And Job Satisfaction Toward Organizational Commitment (A Study On Private Islamic Junior High Schools Teachers In Tangerang Regency). Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 2021, 2, 78–90. [Google Scholar]

- Mapuranga, M.; Maziriri, E.T.; Rukuni, T.F.; Lose, T. Employee Organisational Commitment and the Mediating Role of Work Locus of Control and Employee Job Satisfaction: The Perspective of SME Workers. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovits, Y.; Davis, A.J.; Fay, D.; van Dick, R. The link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: Differences between public and private sector employees. Int. Public Manag. J. 2010, 13, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supartha, W.G.; Sihombing, I.H.H.; Sukerti, N.N. The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment and The Moderating Role of Service Climate. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Business and Management Research (ICBMR 2018), Bali, Indonesia, 7–8 November 2018; Volume 72, pp. 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, Z.; Janati, A.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M.; Khosravizadeh, O. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, organizational justice and self-efficacy among nurses. Nurs. Pract. Today 2019, 6, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Murmann, S.K.; Perdue, R.R. Management commitment and employee perceived service quality: The mediating role of affective Commitment. J. Appl. Manag. Entrep. 2012, 17, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Anees, R.T.; Heidler, P.; Cavaliere, L.P.L.; Nordin, N.A. Brain Drain in Higher Education. The Impact of Job Stress and Workload on Turnover Intention and the Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction at Universities. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.A.; Alzoraiki, M.; Al-shaibah, M.; Almaamari, Q. Enhancing Contextual Performance through Islamic Work Ethics with Mediating role of Normative Commitment. Math. Stat. Eng. Appl. 2022, 71, 8668–8683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoraiki, M.; Ahmad, A.R.; Ateeq, A.A.; Naji, G.M.A.; Almaamari, Q.; Beshr, B.A.H. Impact of Teachers’ Commitment to the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Sustainable Teaching Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.L. Service quality and the training of employees: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albadry, O.M. Strategic Management and Its Impact on University’s Service Quality: The Role of Organisational Commitment; University of Plymouth: Plymouth, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, K.-K.; Tseng, C.-L.; Tsai, H.-P. The Influence of Organizational Elements on Service Delivery to Service Quality: A case study of street level police officer in Kaohsiung city. Mark. Rev./Xing Xiao Ping Lun 2014, 11, 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zopiatis, A.; Constanti, P.; Theocharous, A.L. Job involvement, commitment, satisfaction and turnover: Evidence from hotel employees in Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Bowen, D.E. Employee and customer perceptions of service in banks: Replication and extension. J. Appl. Psychol. 1985, 70, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagenczyk, T.J.; Scott, K.D.; Gibney, R.; Murrell, A.J.; Thatcher, J.B. Social influence and perceived organizational support: A social networks analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2010, 111, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachut, J. Experience and job involvement: Moderators of job satisfaction, job dissatisfaction and intent to stay. Doctor Dissertation, Northcentral University, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.-C.; Shih, C.-H.; Lin, S.-M. The mediating role of psychological empowerment on job satisfaction and organizational commitment for school health nurses: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boles, J.; Madupalli, R.; Rutherford, B.; Andy Wood, J. The relationship of facets of salesperson job satisfaction with affective organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2007, 22, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Chen, C.-J. The relationship between employee commitment and job attitude and its effect on service quality in the tourism industry. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2013, 3, 30131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumrah, A.R.; Boyle, S.; Fein, E.C. The consequences of transfer of training for service quality and job satisfaction: An empirical study in the Malaysian public sector. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2013, 17, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T.; Erculj, V.; Weis, L. Multigroup validation of the service quality, customer satisfaction and performance links in higher education. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 39, 1004–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Page, M.; Brunsveld, N. Essentials of Business Research Methods, 4th ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 3–495. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A Three Component Conceptualization Of Organizational Commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodahl, T.M.; Kejner, M. The definition and measurement of job involvement. J. Appl. Psychol. 1965, 49, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parasuraman, a.; Zeithaml, V.a.; Berry, L.L. SERQUAL: A Multiple-Item scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 1–813. [Google Scholar]

- Nemțeanu, M.-S.; Dinu, V.; Pop, R.-A.; Dabija, D.-C. Predicting Job Satisfaction and Work Engagement Behavior in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Conservation of Resources Theory Approach; Technical University in Liberec: Liberec, Czechia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C.A.; Cromwell, E.A.; Hill, E.; Donkers, K.M.; Schipp, M.F.; Johnson, K.B.; Pigott, D.M.; Hay, S.I. The prevalence of onchocerciasis in Africa and Yemen, 2000–2018: A geospatial analysis. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghumiem, S.H.; Alawi, N.A.M. The Effects of Organizational Commitment on Non-Financial Performance: Insights from Public Sector Context in Developing Countries. J. Int. Bus. Manag. 2022, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ghumiem, S.H.; Alawi, N.A.; Abd, A.-A.; Masaud, K.A. Corporate Culture and Its Effects on Organizational Performance: Multi-Group Analysis Evidence from Developing Countries. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2023, 8, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modelling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; p. 652. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nitzl, C.; Roldan, J.L.; Cepeda, G. Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modelling, Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L. Delivering Quality Service: Balancing Customer Perceptions and Expectations; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, M. Strategic Human Resources Management: A Guide to Action; Kogan Page Ltd.: London, UK, 2006; p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Bono, J.E.; Patton, G.K. The job satisfaction-job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Kim, K. Customer satisfaction, service quality, and customer value: Years 2000–2015. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshoff, C.; Tait, M. Quality perceptions in the financial services sector: The potential impact of internal marketing. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1996, 7, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharahsheh, H.H.; Pius, A. Exploration of employability skills in business management studies within higher education levels: Systematic literature review. Research Anthology on Business and Technical Education in the Information Era. Int. J. Sustain. Econ. Manag. 2021, 9, 52–69. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Dimension | Item | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job Satisfaction (JS) Schnake [38] | Social | The friendliness of the people you work with | JS1 |

| The way you are treated by the people you work with | JS2 | ||

| The respect you receive from the people you work with | JS3 | ||

| Extrinsic | The chances you have to accomplish something worthwhile | JS4 | |

| The amount of pay you get | JS5 | ||

| The fringe benefits you receive | JS6 | ||

| The chance of doing something that makes you feel good about yourself | JS7 | ||

| Intrinsic | The chances you have to take part in making decisions | JS8 | |

| The amount of job security you have | JS9 | ||

| The opportunity to develop your skills and abilities | JS10 | ||

| The amount of freedom you have in your job | JS11 | ||

| Organizational Commitment (OC) Meyer and Allen [1] | Affective | I am very happy to be a member of this university | A1 |

| I feel great loyalty toward this university | A2 | ||

| I would feel guilty if I left my organization now | A3 | ||

| I owe a great deal to my organization | A4 | ||

| Continuance | Leaving university right now would disturb too much of my life | C1 | |

| I could not leave the university right now, even if I wanted to | C2 | ||

| It would be too costly for me to leave my university right now | C3 | ||

| I would be spending the rest of my career at this university | C4 | ||

| Job Involvement (JI) Lodahl and Kejner [2] | My job means a lot more to me than just money | JI1 | |

| 1 am really interested in my work. | JI2 | ||

| I would probably keep working even if I did not need the money | JI3 | ||

| The most important things that happen to me involve my work | JI4 | ||

| For me, the first few hours at work really fly by | JI5 | ||

| I actually enjoy performing the daily activities that make up my job | JI6 | ||

| I look forward to coming to work each day | JI7 | ||

| Service Quality (SQ) Parasuraman, et al. [3] | When lecturers promise to do something by a certain time, they do so | R1 | |

| Reliability | When I have a problem, the lecturer seems sympathetic and reassuring | R2 | |

| The lecturer is dependable | R3 | ||

| The lecturers provided the service at the timeline they promised to do so | R4 | ||

| The lecturers keep accurate records of their work | R5 | ||

| The lecturer tells which series will be performed | Re1 | ||

| Responsiveness | I resave prompt series from the lecturer | Re2 | |

| The lecturer is always willing to help others | Re3 | ||

| The lecturers respond to another request prompt even if they are too busy | Re4 | ||

| Assurance | I can trust the lecturer | As1 | |

| I feel safe in my transactions with the lecturer | As2 | ||

| The lecturer is polite | As3 | ||

| I get adequate support from the lecturer to do my job | As4 | ||

| Empathy | The lecturer gives me individual attention | Em1 | |

| The lecturer gives me personal attention | Em2 | ||

| The lecturer knows my needs | Em3 | ||

| The lecturer has my best interests at heart | Em4 | ||

| The lecturer has operating hours convenient to all his/her students | Em5 |

| Profile | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) | Cumulative (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gander | Male | 215 | 72.6 | 72.6 |

| Female | 81 | 27.4 | 100.0 | |

| Age | 20–29 Years | 13 | 4.4 | 4.4 |

| 30–39 Years | 97 | 32.8 | 37.2 | |

| 40–49 Years | 115 | 38.9 | 76.0 | |

| 50 and above | 71 | 24.0 | 100.0 | |

| Qualification | Bachelor’s | 60 | 20.3 | 20.3 |

| Master’s | 59 | 19.9 | 40.2 | |

| PhD | 177 | 59.8 | 100.0 | |

| Experience | <10 years | 117 | 39.5 | 39.5 |

| >10 years | 179 | 60.5 | 100.0 |

| Variables | N | Mean | Sdr. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Satisfaction | 296 | 3.3885 | 0.42610 | −0.389 | 0.180 | 1.041 |

| Org Commitment | 296 | 3.2255 | 0.45044 | 0.046 | 0.046 | 1.040 |

| Job Involvement | 296 | 3.5507 | 0.62579 | −0.010 | −0.010 | 1.011 |

| Service Quality | 296 | 3.4723 | 0.45335 | −0.036 | −0.036 | - |

| Valid N (listwise) | 296 |

| Measure | Estimate | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN | 1355.572 | -- | -- |

| DF | 886 | -- | -- |

| CMIN/DF | 1.53 | Between 1 and 3 | Excellent |

| CFI | 0.96 | >0.95 | Excellent |

| TLI | 0.95 | >0.95 | Excellent |

| RMSEA | 0.042 | <0.06 | Excellent |

| Construct | Indicators | Loading | CA | CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JS | JS1 | 0.69 | 087 | 0.802 | 0.575 | 0.371 | 0.810 |

| JS2 | 0.75 | ||||||

| JS3 | 0.75 | ||||||

| JS4 | 0.75 | ||||||

| JS5 | 0.84 | ||||||

| JS6 | 0.81 | ||||||

| JS7 | 0.70 | ||||||

| JS8 | 0.68 | ||||||

| JS9 | 0.82 | ||||||

| JS10 | 0.76 | ||||||

| JS11 | 0.71 | ||||||

| OC | A1 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.736 | 0.60 | 0.233 | 0.895 |

| A2 | 0.79 | ||||||

| A3 | 0.80 | ||||||

| A4 | 0.73 | ||||||

| C1 | 0.78 | ||||||

| C2 | 0.74 | ||||||

| C3 | 0.74 | ||||||

| C4 | 0.75 | ||||||

| JI | JI1 | 0.74 | 92 | 0.92 | 0.62 | 0.136 | 0.93 |

| JI2 | 0.76 | ||||||

| JI3 | 0.71 | ||||||

| JI4 | 0.91 | ||||||

| JI5 | 0.80 | ||||||

| JI6 | 0.83 | ||||||

| JI7 | 0.76 | ||||||

| SQ | R1 | 0.81 | 0.95 | 0.816 | 0.528 | 0.371 | 0.829 |

| R2 | 0.83 | ||||||

| R3. | 0.92 | ||||||

| R4 | 0.92 | ||||||

| R5 | 0.94 | ||||||

| Re1 | 0.94 | ||||||

| Re2 | 0.96 | ||||||

| Re3 | 0.96 | ||||||

| Re4 | 0.91 | ||||||

| As1 | 0.89 | ||||||

| As2 | 0.81 | ||||||

| As3 | 0.90 | ||||||

| As4 | 0.90 | ||||||

| Em1 | 0.96 | ||||||

| Em2 | 0.98 | ||||||

| Em3 | 0.89 | ||||||

| Em4 | 0.94 | ||||||

| Em5 | 0.89 |

| Variable | Panel A: Fornell–Larcker Criterion | Panel B: Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JS | JI | OC | SQ | JS | JI | OC | SQ | |

| JS | 0.758 | - | ||||||

| JI | 0.132 | 0.789 | 0.099 | - | ||||

| OC | 0.483 *** | 0.369 *** | 0.827 | 0.415 | 0.301 | - | ||

| SQ | 0.609 *** | 0.314 ** | 0.458 ** | 0.727 | 0.517 | 0.286 | 0.427 | - |

| No | Path | Beta | Sdr.D | t-Value | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | JS → SQ | 0.48 | 0.082 | 4.81 | *** | Supported |

| H2 | JS → OC | 0.52 | 0.081 | 4.92 | *** | Supported |

| H3 | OC → SQ | 0.25 | 0.094 | 2.87 | 0.004 | Supported |

| No | Structural Path | Estimate | S.E. | 95% C.I. | p-Value | Decision | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USD | SD | Lower | Upper | |||||

| H4 | JS → OC → SQ | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.051 | 0.038 | 0.243 | 0.004 | supported |

| Indirect Effect | JS→SQ | JS→OC (a) | OC→SQ (b) | a × b | a × b + c | VAF | Type of Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JS→OC→SQ | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.61 | 0.21 | Partial Mediation |

| No | Relationship | Beta | Sdr.D | t-Value | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H5 | JI→SQ | 0.23 | 0.017 | 5.03 | *** | supported |

| H6 | JS_×_JI→SQ | 0.30 | 0.021 | 6.23 | *** | supported |

| H7 | JS_×_JI→OC | 0.26 | 0.019 | 4.71 | *** | supported |

| H8 | OC_×_JI→SQ | 0.24 | 0.018 | 4.28 | *** | supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-refaei, A.A.-A.; Ali, H.B.M.; Ateeq, A.A.; Alzoraiki, M. An Integrated Mediating and Moderating Model to Improve Service Quality through Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107978

Al-refaei AA-A, Ali HBM, Ateeq AA, Alzoraiki M. An Integrated Mediating and Moderating Model to Improve Service Quality through Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):7978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107978

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-refaei, Abd Al-Aziz, Hairuddin Bin Mohd Ali, Ali Ahmed Ateeq, and Mohammed Alzoraiki. 2023. "An Integrated Mediating and Moderating Model to Improve Service Quality through Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 7978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107978

APA StyleAl-refaei, A. A.-A., Ali, H. B. M., Ateeq, A. A., & Alzoraiki, M. (2023). An Integrated Mediating and Moderating Model to Improve Service Quality through Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment. Sustainability, 15(10), 7978. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107978