A Study on the Effect of Authenticity on Heritage Tourists’ Mindful Tourism Experience: The Case of the Forbidden City

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Heritage Tourism

2.2. Authenticity

2.3. Mindfulness

2.4. Tourist Experience

2.5. Tourist Satisfaction

2.6. Loyalty

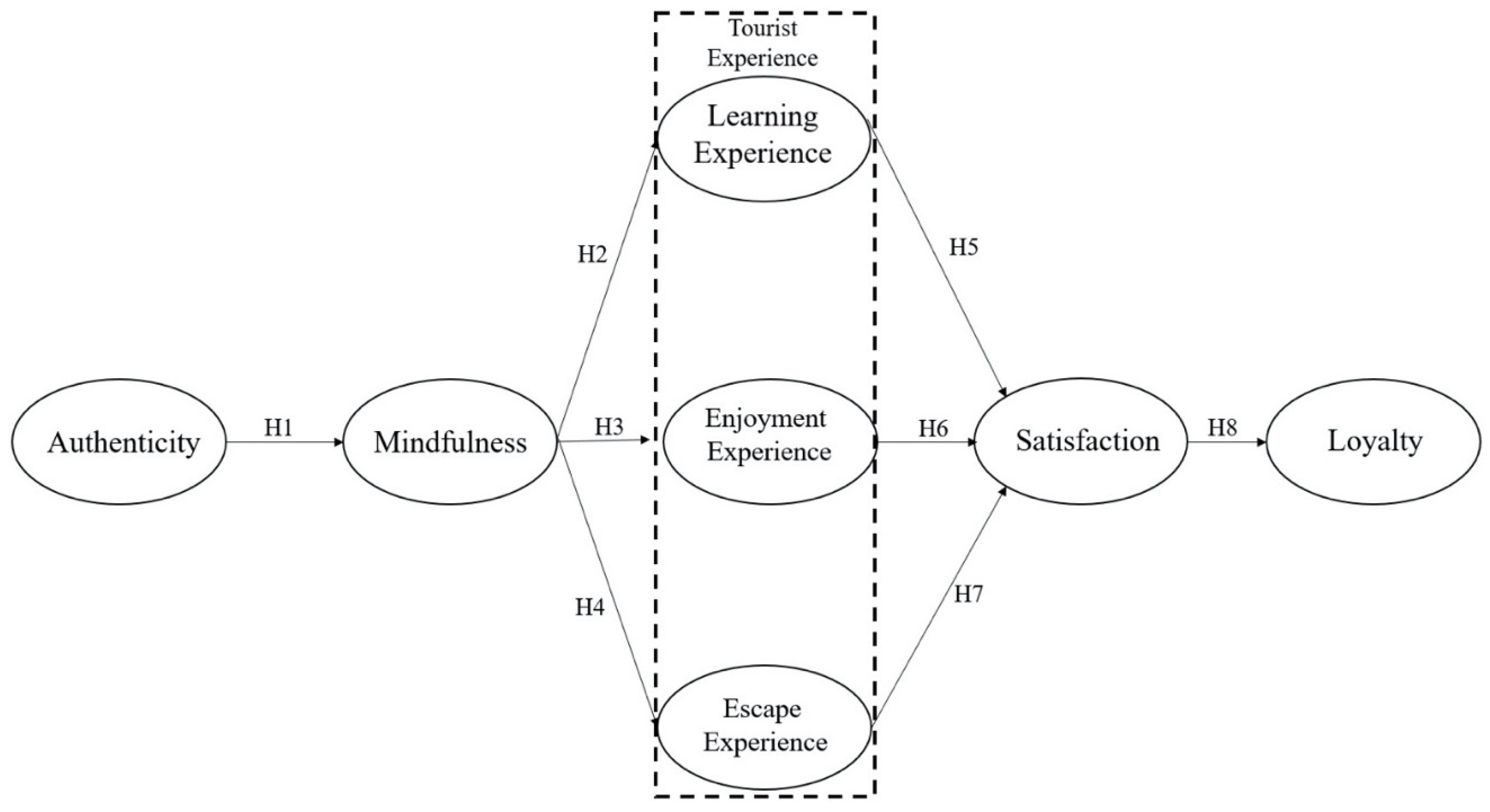

2.7. Hypotheses

2.7.1. Effect of Authenticity on Mindfulness

2.7.2. Effect of Mindfulness on the Tourist Experience

2.7.3. Effect of Tourist Experience on Satisfaction

2.7.4. Effect of Tourists’ Satisfaction on Loyalty

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Site

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Respondents

4.2. Measurement Model Examination

4.3. Structural Model Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, E.; Choi, B.; Lee, T.J. The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, D.; Curran, R.; O’Gorman, K.; Taheri, B. Visitors’ engagement and authenticity: Japanese heritage consumption. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrove, C. Heritage tourism. Cult. Rsc. Manag. 2002, 25, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, S. Cultural and heritage tourism in Canada: Opportunities, principles and challenges. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2002, 3, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Steiner, C.S. Reconceptualizing object authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The eight principles of strategic authenticity. Strategy Leadersh. 2008, 36, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, E. Mindfulness; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Reading, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Moscardo, G. Understanding tourist experience through mindfulness theory. In Handbook of Tourist Behavior; Kozak, M., Decrop, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Sun, S.; Huang, C.; Zou, Z. Authenticity and subjective well-being: The mediating role of mindfulness. J. Res. Pers. 2020, 84, 103900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, S.H.; Langer, E.J. Mindfulness and self-acceptance. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2006, 24, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creating unique value with customers. Strategy Leadersh. 2004, 32, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Gretzel, U. Effects of podcast tours on tourist experiences in a national park. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L. Tourist Behavior: Themes and Conceptual Schemes; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.L.; Schülke, R.; Vatansever, D.; Xi, D.; Yan, J.; Zhao, H.; Xie, X.; Feng, J.; Chen, M.Y.; Sahakian, B.J.; et al. Mindfulness practice for protecting mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baral, N.; Hazen, H.; Thapa, B. Visitor perceptions of world heritage value at Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Nepal. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1494–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, M.A.; Joseph-Mathews, S.M.; Dai, M.; Hayes, S.; Cave, J. Heritage/cultural attraction atmospherics: Creating the right environment for the heritage/cultural visitor. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Lin, X.; Choe, Y.; Li, W. In the eyes of the beholder: The effect of the perceived authenticity of sanfang qixiang in Fuzhou, China, among locals and domestic tourists. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, A. The convergence process in heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 795–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S.; Rather, R.A.; Hall, C.M. Investigating the mediating role of visitor satisfaction in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions in heritage tourism context. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurlin, K. Were culture and heritage important for the resilience of tourism in the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.; Jones, T.E.; Weaver, D.B.; Le, A. The adaptive resilience of living cultural heritage in a tourism destination. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 288, 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickly-Boyd, J. Authenticity & aura: A Benjaminian approach to tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 30, 269–289. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Hu, X.; Lee, H.M.; Zhang, Y. The impacts of ecotourists’ perceived authenticity and perceived values on their behaviors: Evidence from Huangshan World Natural and Cultural Heritage Site. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Phau, I.; Hughes, M.; Li, Y.F.; Quintal, V. Heritage tourism in Singapore Chinatown: A perceived value approach to authenticity and satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. 2016, 33, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, A.; Silk, M.; Chung, C.; Wang, Y.W.; Bailey, R. Chinese perceptions of overseas cultural heritage: Emotive existential authenticity, exoticism and experiential tourism. Leis. Sci. 2023, 45, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Fong, L.H.N.; Gan, M. Rethinking the consequences of postmodern authenticity: The case of a World Cultural Heritage in Augmented Reality. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Yu, J.; Cheng, Q.; Pan, H. The influence mechanism and measurement of tourists’ authenticity perception on the sustainable development of rural tourism—A study based on the 10 most popular rural tourism destinations in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, E.J. Matters of mind: Mindfulness/mindlessness in perspective. Conscious Cogn. 1992, 1, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.L.; Norman, W.C. The influence of mindfulness during the travel anticipation phase. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, C.; Ninov, I. Tourists’ experiences of mindfulness in Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE). J. Travel Tour. 2016, 33, 1195–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Mindful visitors: Heritage and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 376–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Making Visitors Mindful: Principles for Creating Sustainable Visitor Experiences through Effective Communication; Sagamore Publishing: Champaign, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Eyoun, K. Do mindfulness and perceived organizational support work? Fear of COVID-19 on restaurant frontline employees’ job insecurity and emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Errmann, A.; Kim, J.; Lee, D.C.; Seo, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.S. Mindfulness and pro-environmental hotel preference. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 90, 103263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankov, U.; Filimonau, V. Here and now–The role of mindfulness in post-pandemic tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Jiang, L.; Woosnam, K.M.; Eck, T. Volunteer tourists’ revisit intentions explained through emotional solidarity and on-site experience. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 53, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.H.; Foster, D. Using HOLSAT to evaluate tourist satisfaction at destinations: The case of Australian holidaymakers in Vietnam. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehrer, A.; Crotts, J.C.; Magnini, V.P. The perceived usefulness of blog postings: An extension of the expectancy-disconfirmation paradigm. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, S.; Stojanović, V.; Tešin, A.; Šećerov, I.; Pantelić, M.; Dolinaj, D. Memorable tourist experiences in national parks: Impacts on future intentions and environmentally responsible behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Rimmington, M. Tourist satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an off–season holiday destination. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Peterson, R.T. Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: The role of switching costs. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, J.C.; Choi, B.K. How the West sees Jeju: An analysis of Westerners’ perception of Jeju’s personality as a destination. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2016, 16, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.N.; Lee, C.; Chen, H.J. The relationship among tourists’ involvement, place attachment and interpretation satisfaction in Taiwan’s national parks. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Abbas, M.; Abbasi, F.A.; Khan, S. How tourist experience quality, perceived price reasonableness and regenerative tourism involvement influence tourist satisfaction: A study of Ha’il Region, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Eck, T.; An, S. A study on the effect of emotional solidarity on memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty in volunteer tourism. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221087263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, G.; Dincer, F.I. Influence of customer experience on loyalty and word-of-mouth in hospitality operations. Anatolia 2014, 25, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Denizci-Guillet, B.; Ng, E. Rethinking loyalty. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 708–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri-Felitti, D.L.; Fiore, A.M. Destination loyalty: Effects of wine tourists’ experiences, memories, and satisfaction on intentions. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 13, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer–based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, B.; Moscardo, G. Enhancing wildlife education through mindfulness. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2003, 19, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L. Persisting with authenticity: Gleaning contemporary insights for future tourism studies. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2007, 32, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L. Authenticity matters: Meanings and further studies in tourism. In Critical Debates in Tourism; Singh, T.V., Ed.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Breazeale, M.; Radic, A. Happiness with rural experience: Exploring the role of tourist mindfulness as a moderator. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 25, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, D.K. Understanding the exhibition attendees’ evaluation of their experiences: A comparison between high versus low mindful visitors. J. Travel Tour. 2014, 31, 899–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.G.; Romate, J.; Rajkumar, E. Mindfulness-based positive psychology interventions: A systematic review. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, E.; Pocinho, M.; Agapito, D.; Jesus, S.N.D. Positive psychology, well-being, and mindfulness: A successful partnership towards the development of meaningful tourist experiences. J. Tour. Sustain. Welg. 2022, 10, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, S.T.; Chancellor, H.C. Examining the festival attributes that impact visitor experience, satisfaction and re-visit intention. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 15, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Kim, W.G.; Li, J.; Jeon, H.M. Make it delightful: Customers’ experience, satisfaction and loyalty in Malaysian theme parks. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian-Cole, S.; Crompton, J.L.; Willson, V.A. An empirical investigation of the relationships between service quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions among visitors to a wildlife refuge. J. Leis. Res. 2002, 34, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, A.A.M.; Yahaya, M.F. The relationship between airport image, national identity and passengers delight: A case study of the Malaysian low cost carrier terminal (LCCT). J. Air Transp. Manag. 2013, 31, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, A.; Okumus, F.; Wang, Y.; Kwun, D.J.W. Understanding the consumer experience: An exploratory study of luxury hotels. J. Hostp. Mark. 2011, 20, 166–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M. Satisfying and delighting the rural tourists. J. Travel Tour. 2010, 27, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Taylor, S.A. Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Vogt, C.A.; Knutson, B.J. Relationships among customer satisfaction, delight, and loyalty in the hospitality industry. J. Hostp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 170–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, L.; Prete, M.I.; Palmi, P.; Guido, G. Loyal or not? Determinants of heritage destination satisfaction and loyalty. A study of Lecce, Italy. J. Herit. Tour. 2022, 17, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistica. Number of Visitors to the Forbidden City in Beijing 2012–2019. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1175986/yearly-visitors-to-the-palace-museum-in-beijing/ (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Lu, L.; Chi, C.G.; Liu, Y. Authenticity, involvement, and image: Evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Choi, K. The role of authenticity in forming slow tourists’ intentions: Developing an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. A Mindfulness/Mindlessness Model of the Museum Visitor Experience. Ph.D. Thesis, James Cook University, North Queensland, QLD, Australia, 16 February 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Frauman, E.; Norman, W.C. Mindfulness as a tool for managing visitors to tourism destinations. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Liu, Y.C. Deconstructing the internal structure of perceived authenticity for heritage tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2134–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Han, H. Tourist experience quality and loyalty to an island destination: The moderating impact of destination image. J. Travel Tour. 2019, 36, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 60–116. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS: Basic Concept Application and Programming; Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.; Suh, J.; Eck, T. Examining structural relationships among service quality, perceived value, satisfaction and revisit intention for Airbnb guests. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2019, 19, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; An, S.; Eck, T. A study of customer engagement, satisfaction and behavioral intentions among Airbnb users. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2021, 20, 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Choe, Y.; Song, H. Brand behavioral intentions of a theme park in China: An application of brand experience. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Type | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 153 | 42.1 |

| Female | 210 | 57.9 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 195 | 53.7 |

| 25–34 | 39 | 10.7 | |

| 35–44 | 42 | 11.6 | |

| 45–54 | 44 | 12.1 | |

| 55–64 | 22 | 6.1 | |

| >65 | 21 | 5.8 | |

| Visit times | Once | 171 | 47.1 |

| Two times | 99 | 27.3 | |

| Three times | 42 | 11.6 | |

| More than three times | 51 | 14 | |

| Visit duration | 1 h | 31 | 8.5 |

| 2 h | 111 | 30.6 | |

| 3 h | 130 | 35.8 | |

| 4 h | 58 | 16 | |

| Over 5 h | 33 | 9.1 | |

| Accompanied by (multiple) | Alone | 81 | 22.3 |

| responses were allowed | With friends | 175 | 48.2 |

| for this question only) | With family group | 252 | 69.4 |

| Business travel | 39 | 10.7 | |

| Travel by travel agency | 55 | 15.2 | |

| Types of interpretation | Tour guide | 68 | 18.7 |

| Audio guide device | 116 | 32 | |

| Online guide on smartphone | 53 | 14.6 | |

| Printed materials (e.g., booklets, visitor guide map) | 45 | 12.4 | |

| Others | 58 | 16 | |

| Not used | 23 | 6.3 |

| Factors and Items | Standardized Loading | S.E. | Skew. | Kurt. | C.R. | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authenticity | |||||||

| Ancient tradition is well-preserved at the Forbidden City | 0.85 | N/A | −0.743 | 0.551 | N/A | ||

| The Forbidden City is an authentic portrayal of ancient life | 0.82 | 0.05 | −0.906 | 0.972 | 19.30 | 0.93 | 0.72 |

| The Forbidden City presents local history/culture well | 0.89 | 0.05 | −0.949 | 1.878 | 18.63 | ||

| The Forbidden City arouses feelings of authentic history/culture | 0.86 | 0.05 | −0.988 | 1.481 | 18.74 | ||

| I wanted to try the unique cultural experience at the Forbidden City | 0.83 | 0.05 | −0.822 | 0.495 | 19.86 | ||

| Mindfulness | |||||||

| I had my interest captured | 0.82 | N/A | −0.611 | 0.318 | N/A | ||

| I searched for answers to questions I may have had about the Forbidden City | 0.85 | 0.06 | −0.575 | −0.065 | 19.63 | 0.92 | 0.71 |

| I had my curiosity aroused about the Forbidden City | 0.85 | 0.05 | −0.805 | 0.471 | 19.60 | ||

| I inquired further about things in the Forbidden City | 0.84 | 0.06 | −0.678 | −0.009 | 18.98 | ||

| I explored and discovered new things about the Forbidden City | 0.84 | 0.06 | −0.595 | −0.020 | 19.16 | ||

| I felt involved in what was going on around me at the Forbidden City | 0.85 | 0.06 | −0.578 | −0.162 | 19.42 | ||

| Learning experience | |||||||

| I expanded my understanding of the Forbidden City | 0.90 | N/A | −0.930 | 1.693 | N/A | ||

| I gained information and knowledge about the Forbidden City | 0.89 | 0.04 | −0.986 | 1.206 | 25.01 | 0.93 | 0.77 |

| My curiosity about the Forbidden City was enhanced | 0.83 | 0.04 | −0.824 | 1.271 | 24.17 | ||

| I learned many different things about the Forbidden City | 0.88 | 0.04 | −0.898 | 1.523 | 21.82 | ||

| Enjoyment experience | |||||||

| I had fun | 0.91 | N/A | −0.689 | 0.183 | N/A | ||

| I enjoyed being in the Forbidden City | 0.88 | 0.04 | −0.874 | 0.726 | 25.11 | 0.93 | 0.82 |

| I derived a lot of pleasure from the Forbidden City | 0.92 | 0.04 | −0.945 | 1.980 | 25.16 | ||

| Escape experience | |||||||

| I got away from it all | 0.90 | N/A | −0.690 | −0.043 | N/A | 0.86 | 0.75 |

| I got so involved that I forgot everything else at the Forbidden City | 0.83 | 0.04 | −0.545 | −0.395 | 24.79 | ||

| Satisfaction | |||||||

| I felt happy about the trip | 0.93 | N/A | −0.954 | 1.571 | N/A | ||

| I felt satisfied about the trip | 0.94 | 0.04 | −0.901 | 1.428 | 21.99 | 0.94 | 0.81 |

| I felt I had a better understanding of local history/culture after the trip | 0.87 | 0.04 | −0.896 | 1.272 | 25.39 | ||

| I felt my expectation before the trip had been met | 0.85 | 0.05 | −0.832 | 0.670 | 25.52 | ||

| Loyalty | |||||||

| I will recommend the Forbidden City to others | 0.94 | N/A | −0.905 | 1.701 | N/A | ||

| I will say positive things about the Forbidden City | 0.90 | 0.03 | −0.760 | 1.382 | 29.80 | ||

| I will visit the Forbidden City again | 0.86 | 0.04 | −0.854 | 1.336 | 26.43 | ||

| I intend to revisit the Forbidden City in the future | 0.80 | 0.04 | −0.529 | 0.085 | 29.80 | 0.93 | 0.77 |

| Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 587.729, df = 310, χ2/df = 1.90, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.90, NFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.97, RFI = 0.93, RMR = 0.0027, RMSEA = 0.050 | |||||||

| Measures | AU | MI | LE | EJE | EE | SA | LO |

| Authenticity | 0.85 | ||||||

| Mindfulness | 0.66 | 0.84 | |||||

| Learning experience | 0.74 | 0.61 | 0.88 | ||||

| Enjoyment experience | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.91 | |||

| Escape experience | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.87 | ||

| Satisfaction | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.72 | 0.43 | 0.90 | |

| Loyalty | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.43 | 0.78 | 0.88 |

| Hypothesized Path | Standardized Estimates | t | Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Authenticity → mindfulness | 0.73 | 13.20 *** | Yes |

| H2: Mindfulness → learning experience | 0.70 | 13.39 *** | Yes |

| H3: Mindfulness → enjoyment experience | 0.77 | 14.55 *** | Yes |

| H4: Mindfulness → escape experience | 0.65 | 10.83 *** | Yes |

| H5: Learning experience → satisfaction | 0.15 | 3.07 * | Yes |

| H6: Enjoyment experience → satisfaction | 0.68 | 12.03 *** | Yes |

| H7: Escape experience → satisfaction | −0.05 | −0.95 | No |

| H8: Satisfaction → loyalty | 0.79 | 16.70 *** | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eck, T.; Zhang, Y.; An, S. A Study on the Effect of Authenticity on Heritage Tourists’ Mindful Tourism Experience: The Case of the Forbidden City. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107756

Eck T, Zhang Y, An S. A Study on the Effect of Authenticity on Heritage Tourists’ Mindful Tourism Experience: The Case of the Forbidden City. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):7756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107756

Chicago/Turabian StyleEck, Thomas, Yiwen Zhang, and Soyoung An. 2023. "A Study on the Effect of Authenticity on Heritage Tourists’ Mindful Tourism Experience: The Case of the Forbidden City" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 7756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107756

APA StyleEck, T., Zhang, Y., & An, S. (2023). A Study on the Effect of Authenticity on Heritage Tourists’ Mindful Tourism Experience: The Case of the Forbidden City. Sustainability, 15(10), 7756. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107756