Under the Risk of COVID-19 Epidemic: A Study on the Influence of Life Attitudes, Leisure Sports Values, and Workplace Risk Perceptions on Urban Development and Public Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Sustainable Influence of Life Behavior, Work Attitudes, and Leisure Values on the Construction of a Happy Urban City

1.2. Research Innovation and Importance

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Life Attitude

2.2. Leisure Sports Values

2.3. Risks of Job Seeking and Workplace

2.4. Well-Being

2.5. Rural and Urban Development Impact

3. Methods

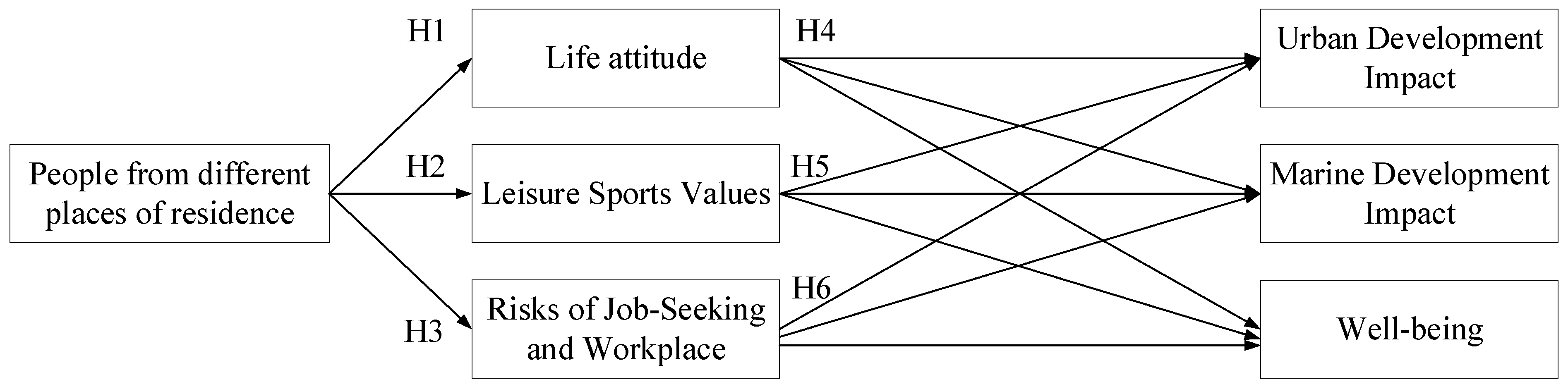

3.1. Framework

3.2. Hypothesis

3.3. Process, Methods, and Tools

3.4. Scope and Limitations

3.5. Ethical Considerations

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Analysis of Public Life Attitudes, Leisure Values, and Workplace Risk Perceptions

4.2. Analysis of the Correlation between Life Attitudes, Leisure Values, Workplace Risks, Urban Development, and Well-Being

5. Discussion

5.1. Life Attitudes, Leisure Values, and Workplace Risks (Job-Seeking and Workplace Risks): Perceptions of the Public

5.1.1. Cognition of Life Attitudes

5.1.2. Leisure and Sports Values

5.1.3. Job-Seeking and Workplace Risk Perception

5.2. The Effects of Life Attitudes, Leisure Values, and Workplace Risks on the Effectiveness of Urban Development and Well-Being

5.2.1. Analysis of the Correlation between Life Attitudes and Urban Development and Well-Being

5.2.2. Analysis of the Correlation between Leisure Values and Urban Development and Happiness

5.2.3. Analysis of the Correlation between Job-Seeking and Employment Risk Perceptions and Urban Development and Happiness

6. Conclusions

6.1. About Government and Business

6.2. About Educational Institutions and Citizens

6.3. Research Limitations and Recommendations for Follow-Up Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thuiller, W. Climate change and the ecologist. Nature 2007, 448, 550–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, P. COVID-19 timeline of events. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 2054–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, A. Where Will War Break Out Next? Predicting Violent Conflict. Available online: https://asiafoundation.org/2022/10/26/where-will-war-break-out-next-predicting-violent-conflict/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Stapczynski, S.; Shiryaevskaya, A.; Mangi, F. Europe’s Energy Crunch Will Trigger Years of Shortages and Blackouts. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-11-08/eu-energy-crisis-sparked-by-ukraine-war-to-create-blackouts-in-poor-countries?leadSource=uverify%20wall (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Bhardwaj, V.K.; Yadav, D.L. COVID-19 and the Global Stagnation: Labour Migration, Economic Recession and Its Implications. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3610508 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H. Impacts of the Russia-Ukraine War on Global Food Security: Towards More Sustainable and Resilient Food Systems? Foods 2022, 11, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Geng, Y.; Xia, X.Q.; Wang, Q.J. Economic Policy Uncertainty, Social Development, Political Regimes and Environmental Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jevtic, M.; Matkovic, V.; Kusturica, M.P.; Bouland, C. Build Healthier: Post-COVID-19 Urban Requirements for Healthy and Sustainable Living. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, H.-L.; Shen, C.-C. Exploring the Influence of Perceived Epidemic Severity and Risk on Well-Being in Nature-Based Tourism—Taking China’s Post-1990 Generation as an Example. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Urban planning and quality of life: A review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being. Cities 2021, 115, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X. Promoting Environmental Protection through Art: The Feasibility of the Concept of Environmental Protection in Contemporary Painting Art. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 3385624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.Y. The Digital Nomad Lifestyle: (Remote) Work/Leisure Balance, Privilege, and Constructed Community. Int. J. Sociol. Leis. 2018, 2, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitus, K. Forming the capacity to aspire: Young refugees’ narratives of family migration and wellbeing. J. Youth Stud. 2021, 25, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.Y. The interurban migration industry: ‘Migration products’ and the materialisation of urban speculation at Iskandar Malaysia. Urban Stud. 2021, 59, 2199–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, J.; Zheng, M. Green Governance: New Perspective from Open Innovation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grum, B.; Grum, D.K. Concepts of social sustainability based on social infrastructure and quality of life. Facilities 2020, 38, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstübici, A.; Elçi, E. Aspirations Among Young Refugees in Turkey: Social Class, Integration and Onward Migration in Forced Migration Contexts. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2022, 48, 4865–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Yu, T.; Xiao, R. Structure Reversal of Online Public Opinion for the Heterogeneous Health Concerns under NIMBY Conflict Environmental Mass Events in China. Healthcare 2020, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraouf, A.A. The new normal or the forgotten normal: Contesting COVID-19 impact on contemporary architecture and urbanism. Int. J. Arch. Res. Archnet-IJAR 2021, 15, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Q.; Jian, C. Natural resource endowment, institutional quality and China’s regional economic growth. Resour. Policy 2020, 66, 101644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, A.; Kern, M.L.; Neville, B.A. CSR for Happiness: Corporate determinants of societal happiness as social responsibility. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2020, 29, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, T.L.; Froude, E.; Trollor, J.; Foley, K.R. Foley. Leisure participation and satisfaction in autistic adults and neurotypical adults. Autism 2019, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurawik, M. Moving through spaces—leisure walking and its psychosocial benefits for well-being: A narrative review. Hum. Mov. 2020, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glowacz, F.; Schmits, E. Psychological distress during the COVID-19 lockdown: The young adults most at risk. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Győri, F. Health–Sports–Tourism: With the Prospects of Hungary. Foundation for Youth Activity and Lifestyle, Szeged, 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ferenc-Gyori/publication/350053543_Health-Sports-Tourism_with_the_Prospects_of_Hungary/links/604e282092851c2b23cd3808/Health-Sports-Tourism-with-the-Prospects-of-Hungary.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Hurly, J. ‘I feel something is still missing’: Leisure meanings of African refugee women in Canada. Leis. Stud. 2019, 38, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvo, D.; Garcia, L.; Reis, R.S.; Stankov, I.; Goel, R.; Schipperijn, J.; Hallal, P.C.; Ding, D.; Pratt, M. Physical Activity Promotion and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: Building Synergies to Maximize Impact. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 1163–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenelle, A.J.; Janko, E.; Kowalski, K.C. Good jobs, scam jobs: Detecting, normalizing, and internalizing online job scams during the COVID-19 pandemic. New Media Soc. 2022, 24, 1591–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, B.; Khan, C. Youth underemployment: A review of research on young people and the problems of less(er) employment in an era of mass education. Sociol. Compass 2021, 15, e12921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, K.A.; Abreu, R.L.; Rosario, C.C.; Koech, J.M.; Lockett, G.M.; Lindley, L. “A center for trans women where they help you”: Resource needs of the immigrant Latinx transgender community. Int. J. Transgender Health 2022, 23, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kang, S.W. Perceived Crowding and Risk Perception According to Leisure Activity Type during COVID-19 Using Spatial Proximity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuff, S.F.; Tucker, J.A.; Murphy, J.G. Behavioral economics of substance use: Understanding and reducing harmful use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 29, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.W.; Lin, H.H.; Chen, C.C.; Lee, P.Y.; Hsu, C.H. How to improve the problem of hotel manpower shortage in the COVID-19 epidemic environment? Exploring the effectiveness of the hotel practice training system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 72169–72184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Martín, P.P. Going beyond the Smart City? Implementing Technopolitical Platforms for Urban Democracy in Madrid and Barcelona. Sustain. Smart City Transit. 2022, 280–299. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/oa-edit/10.4324/9781003205722-14/going-beyond-smart-city-implementing-technopolitical-platforms-urban-democracy-madrid-barcelona-adrian-smith-pedro-prieto-mart%C3%ADn (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Lin, C.; Zhao, G.; Yu, C.; Wu, Y.J. Smart City Development and Residents’ Well-Being. Sustainability 2019, 11, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrbe, R.U.; Neumann, I.; Grunewald, K.; Brzoska, P.; Louda, J.; Kochan, B.; Macháč, J.; Dubová, L.; Meyer, P.; Brabec, J.; et al. The Value of Urban Nature in Terms of Providing Ecosystem Services Related to Health and Well-Being: An Empirical Comparative Pilot Study of Cities in Germany and the Czech Republic. Land 2021, 10, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glebova, E.; Zare, F. Career paths in sport management: Trends, typology, and trajectories, Journal of Physical Education and Sport. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2023, 23, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, K.; Pusztai, G. An empirical study of Bourdieu’s theory on capital and habitus in the sporting habits of higher education students learning in Central and Eastern Europe. Sport Educ. Soc. 2023, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-H.; Chang, K.-H.; Tseng, C.-H.; Lee, Y.-S.; Hung, C.-H. Can the Development of Religious and Cultural Tourism Build a Sustainable and Friendly Life and Leisure Environment for the Elderly and Promote Physical and Mental Health? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-H.; Lin, H.-H.; Jhang, S.-W.; Lin, T.-Y. Does environmental engineering help rural industry development? Discussion on the impact of Taiwan’s “special act for forward-looking infrastructure” on rural industry development. Water 2020, 12, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-H.; Hsu, C.-H.; Liu, C.-Y.; Cheng, B.-Y.; Wang, C.-H.; Liu, J.-M.; Jhang, S. The Impact of Cultural Festivals on the Development of Rural Tourism—A Case Study of Da Jia Matsu Pilgrimage. IOP Conf. Series Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 526, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Shao, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, G.; Zhang, W. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: A literature review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 114, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.J.; Lin, H.H.; Hsu, I.C.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, S.F.; Li, Q.Y. River green land and its influence on urban economy, leisure development, ecological protection, and the well-being of the elderly. Water 2023, 15, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.K.; Gazi, A.I.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Rahaman, A. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on tourist travel risk and management perceptions. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, M.F.; Perreault, G.P. Journalists on COVID-19 Journalism: Communication Ecology of Pandemic Reporting. Am. Behav. Sci. 2021, 65, 976–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocian, K.; Baryla, W.; Wojciszke, B. Egocentrism shapes moral judgements. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2020, 149, e12572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankovsky, M. Recognition as a Philosophical Practice: From “Warring” Attitudes to Cooperative Projects. Crit. Horizons 2021, 22, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.C. The Relationship of the Life Attitude on Leisure Motivation and Constraints in New Taipei City Polytechnic College Students. Master’s Thesis, Taipei City University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2014. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11296/6u4m6b (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, F.J. Ethics and Behavioural Theory: How Do Professionals Assess Their Mental Models? J. Bus. Ethic 2019, 157, 933–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochstetler, D. Coaching Philosophy, Values, and Ethics. Coaching for Sports Performance, 2019. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429299360-2/coaching-philosophy-values-ethics-douglas-hochstetler (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, S.T.; Liu, Y. Spatial pattern of leisure activities among residents in Beijing, China: Exploring the impacts of urban environment. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S.A.; Swann, C. Time for mental healthcare guidelines for recreational sports: A call to action. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolanin, A. Quality of Life in Selected Psychological Concepts. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Q. 2021, 28, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janis, I.L. Psychological Stress: Psychoanalytic and Behavioral Studies of Surgical Patients; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar, K.; Kumar, A. Employer brand, person-organisation fit and employer of choice: Investigating the moderating effect of social media. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, A.M.; Marzouk, A.M.; Khalifa, G.S.A. Antecedents of Employees’ Perception and Attitude to Risks: The Experience of Egyptian Tourism and Hospitality Industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 24, 330–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.-F. A Study of University Graduating Student’s Working Holiday and Overseas Employment Risk and Employment Assistance. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Culture University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2017. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11296/57777n (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Rundmo, T. Risk perception and safety on offshore petroleum platforms—Part II: Perceived risk, job stress and accidents. Saf. Sci. 1992, 15, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmbold, L.R. Making Choices, Making Do: Survival Strategies of Black and White Working-Class Women during the Great Depression; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mackie, A. Young People, Youth Work and Social Justice: A Participatory Parity Perspective. PhD Thesis, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1842/36184 (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Tech, R.R.M.; Theophilos, C. Preventing Bullying: A Manual for Teachers in Promoting Global Educational Harmony; Balboa Press: Bloomington, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge, K.C. Evolving Concepts of Emotion and Motivation. Front. Psychol 2018, 9, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.-K.; Liu, Y.; Kang, S.; Dai, A. The Role of Perceived Smart Tourism Technology Experience for Tourist Satisfaction, Happiness and Revisit Intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-T.; Chen, H.-C.; Hsu, N.-W.; Chou, P. Volunteering and self-reported health outcomes among older people living in the community: The Yilan study, Taiwan. Qual. Life Res. 2022, 31, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, F.M.; Withey, S.B. Social Indicators of Well-Being: Americans’ Perceptions of Life Quality; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, R.; Hadjar, A. How Welfare-State Regimes Shape Subjective Well-Being Across Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 129, 565–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airenti, G. The Development of Anthropomorphism in Interaction: Intersubjectivity, Imagination, and Theory of Mind. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Long, K. Farmers’ identity, property rights cognition and perception of rural residential land distributive justice in China: Findings from Nanjing, Jiangsu Province. Habitat Int. 2018, 79, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashan, D.; Colléony, A.; Shwartz, A. Urban versus rural? The effects of residential status on species identification skills and connection to nature. People Nat. 2021, 3, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.H.; Ting, K.C.; Huang, J.M.; Chen, I.S.; Hsu, C.H. Influence of Rural Development of River Tourism Resources on Physical and Mental Health and Consumption Willingness in the Context of COVID-19. Water 2022, 14, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Zare, H.; Guan, C.; Gaskin, D. The impact of rural-urban community settings on cognitive decline: Results from a nationally-representative sample of seniors in China. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.C.; Lin, H.H.; Lu, S.Y.; Chien, J.H.; Shen, C.C. Research on the current situation of rural tourism in southern Fujian in China after the COVID-19 epidemic. Open Geosci. 2022, 14, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, H.; Yang, J.; Nielsson, E.T. The Polar Silk Road: China’s New Frontier of International Cooperation. China Q. Int. Strat. Stud. 2018, 4, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.C.; Tseng, C.H.; Lin, H.H.; Perng, Y.S.; Tseng, Y.H. Suggestions on Relieving Physical Anxiety of Medical Workers and Improving Physical and Mental Health Under the COVID-19 Epidemic—A Case Study of Meizhou City. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 919049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.H.; Lee, S.S.; Perng, Y.S.; Yu, S.T. Investigation about the Impact of Tourism Development on a Water Conservation Area in Taiwan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.T.; Pan, P.Y. The Application of Hybrid Research in Educational Research. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2010, 55, 97–130. Available online: http://jntnu.ord.ntnu.edu.tw/Uploads/Papers/634594728241118000.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Ting, K.C.; Lin, H.H.; Chien, J.H.; Tseng, K.C.; Hsu, C.H. How can sports entrepreneurs achieve their corporate sustainable development goals under the COVID-19 epidemic? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 29, 72101–72116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.H.; Hsu, I.C.; Lin, T.Y.; Tung, L.M.; Ling, Y. After the Epidemic, Is the Smart Traffic Management System a Key Factor in Creating a Green Leisure and Tourism Environment in the Move towards Sustainable Urban Development? Sustainability 2022, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Lin, H.H.; Jhang, S. Sustainable Tourism Development in Protected Areas of Rivers and Water Sources: A Case Study of Jiuqu Stream in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Lin, H.H.; Wang, C.C.; Jhang, S. How to Defend COVID-19 in Taiwan? Talk about People’s Disease Awareness, Attitudes, Behaviors and the Impact of Physical and Mental Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marescaux, E.; De Winne, S.; Forrier, A. Developmental HRM, employee well-being and performance: The moderating role of developing leadership. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2019, 16, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourism Promotion Bureau of the People’s Government of Sanya City. Sanya Tourism Statistics Monthly Report June 2022. Available online: https://www.visitsanya.com/display.php?id=407 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Hainan Statistics Bureau. Hainan Announces the Main Data Results of the Seventh National Census Haikou. Available online: https://population.gotohui.com/pdata-123 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Xie, Y.-L. Physical Conflicts Caused by Taking Pictures to Compete for Customers! Sanya Police: 6 People were Detained for 15 Days. Available online: https://bj.bjd.com.cn/5b165687a010550e5ddc0e6a/contentShare/5b16573ae4b02a9fe2d558f9/AP63bd218ae4b0fb99eeb321df.html (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Zeng, J.-J. A Man was Detained by the Sanya Police for Tearing up the Epidemic Prevention and Control Seal without Authorization. Available online: https://news.bjd.com.cn/2022/08/16/10134971.shtml (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Lai, J.-H. Hainan Notified Three Violations of Epidemic Prevention and Control Disciplines, and Many People were Brought to Justice. Available online: https://money.udn.com/money/story/5612/6537969?from=edn_previous_story (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Ren, M.-C. Sanya City Government Wants to Recycle 6-Year-Old Cooperative Projects, Developer Says Crossing the River and Destroying Bridges. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2016-12/08/c_1120076543.htm (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Bower, I.; Tucker, R.; Enticott, P.G. Impact of built environment design on emotion measured via neurophysiological correlates and subjective indicators: A systematic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 66, 101344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Administrative Divisions of China—Provincial Administrative Units. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/test/2009-04/17/content_1288035.htm (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- General Administration of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. My Country’s Population Development Presents New Characteristics and New Trends. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/sjjd/202105/t20210513_1817394.html (accessed on 14 November 2022).

| Structure (α) | City Classification and Connotation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | Residence | First-tier cities (C1): top 4 cities in China based on economic volume. New first-tier cities (NC1): cities in China with high business concentration, urban hubs, active people, diversity, and plasticity of life. Second-tier cities (C2): regional center cities with dynamic development or advanced economy. Third-tier cities (C3): medium- and large-sized cities with strategic significance, relatively well-developed economy, and large economic volume. Fourth-tier Cities (C4): medium-sized cities with relatively common urban size, economic and social development levels, and transportation facilities. Fifth-tier Cities (C5): cities with a relatively poor economic base, insufficient transportation, limited number of large enterprises, and mainly agricultural industries. | |||||

| Structure (α/σ2) | Substructure (α/σ2) | Issues | KMO | Bartlett | Cronbach α | ||

| Cognition of life attitude (0.914/73.7%) | Willing to contribute to society without compensation, priority of interests for hometown people, priority of self-interest, and priority of health over work | 0.830 | 2553.47 * | 0.864–0.912 | |||

| Leisure sports values (0.855/60.3%) | Maintain physical and mental health, improve interpersonal interaction, enhance the quality of life, and learn leisure or sports skills | 0.814 | 1421.88 * | 0.790–0.845 | |||

| Job-seeking risks (0.959/77.32%) | Job requirements and demands (0.956/35.60%) | Workplace expertise as the main consideration for job seeking, workplace connections as the main consideration for job seeking, and workplace salary as the main consideration for job seeking | 0.940 | 9896.15 * | 0.954–0.956 | ||

| Job seeking expectations and attitude (0.955/35.49%) | Improve social status, job security, and quality of life | 0.940–0.955 | |||||

| Job seeking goals and behaviors (0.957/6.3%) | Contribute to the city, impart professional knowledge and experience, and alleviate the financial burden of family members | 0.954–0.957 | |||||

| Workplace risks (0.920/82.12%) | Right to competitive work (0.920/51.43%) | Foreign job seekers squeeze out job opportunities for locals, and foreign job seekers cause hardship, health, or physical strain on locals | 0.927 | 8396.25 * | 0.886–0.908 | ||

| Stress in the workplace (0.920/30.69%) | Being discriminated against/discriminating against migrants, conflict, normality of a competitive environment, greater scope of a migrant’s work or business, variety of migrants’ workload, and shorter working hours of migrants | 0.889–0.918 | |||||

| Urban development impact (0.974/82.72%) | Economics (0.971/31.57%) | Complement development funds, improve the quality of human resources in the employment market, and enhance public facilities | 0.961 | 11,163.5 * | 0.969–0.971 | ||

| Society (0.972/27.83%) | Promote cultural and artistic interaction, value cultural history and monuments, and build consensus among the public | 0.970–0.972 | |||||

| Environment (0.973/23.2%) | Improve the living environment, improve transportation, and improve health and medical care. | 0.968–0.974 | |||||

| Rural development (0.974/80.05%) | Strengthen ecological conservation, reduce pollution and waste. | 0.950 | 15,224.5 * | 0.945–0.950 | |||

| Well-being (0.965/90.2%) | Improve quality of life, physical and mental health, and self-confidence | 0.782 | 2894.2 * | 0.943–0.953 | |||

| Identity | Gender | Residence time/years of work experience | Identity | Gender | Residence time/years of work experience | ||

| Professor/resident (P1) | Male | 15 | Resident (R1) | Male | 40 | ||

| Professor/resident (P2) | Female | 20 | Resident (R2) | Female | 38 | ||

| Professor/migrants (P3) | Male | 15 | Migrants (M1) | Male | 5 | ||

| Professor/migrants (P4) | Female | 10 | Migrants (M2) | Female | 6 | ||

| Facet | Sub-Facet | Issue | M | SD | Rank | First-Tier | New First-Tier | Second-Tier | Third-Tier | Fourth-Tier | Fifth-Tier | p-Value | Post Hoc Tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life attitudes | Willingness to contribute without compensation to society | 3.85 | 1.083 | 4 | 3.83 ● | 3.06 ● | 3.81 ● | 3.99 ● | 3.82 ● | 3.89 ● | 0.021 * | First-tier cities, second-tier cities, third-tier cities, fourth-tier cities, fifth-tier cities > new first-tier cities | |

| Prioritize the interests of hometown people | 3.95 | 1.062 | 3 | 3.83 ● | 3.32 | 3.91 | 4.11 | 3.93 | 3.97 | 0.011 * | Third-tier cities > New first-tier cities | ||

| Prioritize their own interests | 4.01 | 1.088 | 2 | 3.83 ● | 3.09 | 3.93 | 4.23 ★ | 4.02 | 4.09 ★ | 0.013 * | First-tier cities, second-tier cities, third-tier cities, fourth-tier cities, fifth-tier cities > new first-tier cities; third-tier cities > first-tier cities | ||

| Prioritize health as a work priority | 4.13 | 0.900 | 1 | 4.12 ★ | 4.41 ★ | 3.94 ★ | 4.20 | 4.12 ★ | 4.09 ★ | 0.004 | N/A | ||

| Leisure values | Maintain physical and mental health of individuals | 4.11 | 0.950 | 1 | 4.09 ★ | 4.41 ★ | 3.92 ★ | 4.20 ★ | 4.04 ★ | 4.09 ★ | 0.164 | N/A | |

| Promote interpersonal interaction | 3.85 | 1.046 | 4 | 3.83 ● | 3.38 ● | 3.83 | 4.06 | 3.72 ● | 3.79 ● | 0.012 * | Third-tier cities > New first-tier cities, Fourth-tier cities | ||

| Enhance quality of life | 3.88 | 0.989 | 5 | 3.92 | 3.79 | 3.67 ● | 3.97 | 3.83 | 3.89 | 0.000 | N/A | ||

| Learn leisure or sports skills | 3.89 | 0.893 | 2 | 3.94 | 4.15 | 3.81 | 3.93 ● | 3.73 | 3.99 | 0.011 | N/A | ||

| Job-seeking risks | Job requirements and demands | Workplace expertise as the main consideration in job seeking | 3.95 | 0.864 | 2 | 4.01 | 4.03 ● | 3.88 | 4.07 ★ | 3.76 | 3.99 ● | 0.011 * | third-tier > fourth-tier |

| Career connections as the main consideration for job seeking | 3.92 | 0.886 | 3 | 3.94 ● | 4.18 | 3.77 ● | 4.03 | 3.74 ● | 4.00 ★ | 0.167 * | third-tier > fourth-tier | ||

| Salary as the main consideration for job seeking | 4.00 | 0.882 | 1 | 4.02 ★ | 4.38 ★ | 4.06 ★ | 4.02 ● | 3.86 ★ | 4.00 ★ | 0.042 | N/A | ||

| Job-seeking expectations and attitude | Enhancement of social status | 3.89 | 0.920 | 3 | 4.02 ● | 3.76 ● | 3.84 ● | 3.91 ● | 3.80 ● | 3.97 ● | 0.131 | N/A | |

| Improve job security | 4.17 | 0.817 | 2 | 4.27 | 4.35 ★ | 4.14 | 4.08 | 4.10 | 4.33 ★ | 0.020 | N/A | ||

| Improve quality of life | 4.22 | 0.827 | 1 | 4.35 ★ | 4.15 | 4.15 ★ | 4.19 ★ | 4.17 ★ | 4.32 | 0.252 | N/A | ||

| Job-seeking goals and behaviors | Contribute to the city | 3.99 | 0.850 | 3 | 4.06 ● | 3.76 ● | 4.00 ● | 4.03 ● | 3.88 ● | 4.05 ● | 0.000 | N/A | |

| Transfer of expertise and experience | 4.08 | 0.838 | 2 | 4.11 | 4.09 ★ | 4.08 | 4.13 | 3.94 | 4.16 | 0.006 | N/A | ||

| Alleviate the financial burden of family members | 4.18 | 0.830 | 1 | 4.29 ★ | 4.09 ★ | 4.24 ★ | 4.20 ★ | 4.06 ★ | 4.21 ★ | 0.504 | N/A | ||

| Workplace risk | Right to competitive work | Foreign job seekers will squeeze job opportunities for locals | 3.21 | 1.289 | 3 | 3.34 ● | 2.97 ● | 2.90 ● | 3.19 ● | 3.18 ● | 3.48 | 0.005 | N/A |

| Foreign job seekers would cause hardship to locals | 3.37 | 1.223 | 2 | 3.61 ★ | 3.44 ★ | 3.20 | 3.34 | 3.23 | 3.50 ★ | 0.004 | N/A | ||

| Increased health or physical load | 3.39 | 1.184 | 1 | 3.51 | 3.26 | 3.33 ★ | 3.40 ★ | 3.32 ★ | 3.44 ● | 0.001 | N/A | ||

| Stress in the workplace | Discriminated against migrants | 3.32 | 1.127 | 5 | 3.33 | 3.68 | 3.15 ● | 3.29 | 3.29 | 3.46 | 0.711 | N/A | |

| Conflicts | 3.28 | 1.149 | 6 | 3.25 ● | 3.62 ● | 3.37 | 3.19 ● | 3.25 ● | 3.38 ● | 0.495 | N/A | ||

| Competitive environment ambience constantly | 3.46 | 1.111 | 4 | 3.45 | 3.85 ★ | 3.42 | 3.43 | 3.38 | 3.58 | 0.504 | N/A | ||

| Larger work range | 3.51 | 1.020 | 3 | 3.53 | 3.74 | 3.47 | 3.50 ★ | 3.41 | 3.63 | 0.060 | N/A | ||

| Heavy workload | 3.53 | 1.010 | 1 | 3.56 ★ | 3.76 | 3.57 ★ | 3.47 | 3.44 ★ | 3.68 ★ | 0.002 | N/A | ||

| Insufficient working time | 3.52 | 1.049 | 2 | 3.50 | 3.79 | 3.45 | 3.50 ★ | 3.42 | 3.73 | 0.239 | N/A | ||

| Urban Development Impact | Economic Impact | Social Impact | Environmental Impact | Rural Development Impact | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life attitudes | 0.572 ** | 0.564 ** | 0.552 ** | 0.544 ** | 0.485 ** |

| Leisure values | 0.620 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.595 ** | 0.596 ** | 0.634 ** |

| Job-seeking risks | 0.739 ** | 0.716 ** | 0.711 ** | 0.711 ** | 0.562 ** |

| Job requirements and demands | 0.721 ** | 0.702 ** | 0.685 ** | 0.697 ** | 0.594 ** |

| Job-seeking expectations and attitude | 0.643 ** | 0.619 ** | 0.617 ** | 0.622 ** | 0.416 ** |

| Job-Seeking goals and behaviors | 0.684 ** | 0.663 ** | 0.669 ** | 0.651 ** | 0.467 ** |

| Workplace risk | 0.488 ** | 0.465 ** | 0.453 ** | 0.484 ** | 0.467 ** |

| Right to competitive work | 0.553 ** | 0.550 ** | 0.525 ** | 0.527 ** | 0.530 ** |

| Stress in the workplace | 0.620 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.595 ** | 0.596 ** | 0.491 ** |

| Well-Being | Effectively Enhance Quality of Life | Improve Physical and Mental Health | Increase Self-Confidence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life attitude | 0.533 ** | 0.528 ** | 0.518 ** | 0.500 ** |

| Leisure values | 0.579 ** | 0.576 ** | 0.564 ** | 0.541 ** |

| Job-seeking risks | 0.710 ** | 0.697 ** | 0.680 ** | 0.682 ** |

| Job requirements and demands | 0.677 ** | 0.666 ** | 0.656 ** | 0.641 ** |

| Job-seeking expectations and attitude | 0.645 ** | 0.632 ** | 0.614 ** | 0.627 ** |

| Job-seeking goals and Behaviors | 0.645 ** | 0.634 ** | 0.613 ** | 0.624 ** |

| Workplace risk | 0.388 ** | 0.382 ** | 0.370 ** | 0.373 ** |

| Right to competitive work | 0.377 ** | 0.370 ** | 0.364 ** | 0.360 ** |

| Stress in the workplace | 0.579 ** | 0.576 ** | 0.564 ** | 0.541 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Zheng, Y.-Z.; Lin, H.-H.; Chen, I.-S.; Chen, K.-Y.; Li, Q.-Y.; Tsai, I.-E. Under the Risk of COVID-19 Epidemic: A Study on the Influence of Life Attitudes, Leisure Sports Values, and Workplace Risk Perceptions on Urban Development and Public Well-Being. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107740

Yang L, Zheng Y-Z, Lin H-H, Chen I-S, Chen K-Y, Li Q-Y, Tsai I-E. Under the Risk of COVID-19 Epidemic: A Study on the Influence of Life Attitudes, Leisure Sports Values, and Workplace Risk Perceptions on Urban Development and Public Well-Being. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):7740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107740

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Lu, Yong-Zhan Zheng, Hsiao-Hsien Lin, I-Shen Chen, Kuan-Yu Chen, Qi-Yuan Li, and I-En Tsai. 2023. "Under the Risk of COVID-19 Epidemic: A Study on the Influence of Life Attitudes, Leisure Sports Values, and Workplace Risk Perceptions on Urban Development and Public Well-Being" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 7740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107740

APA StyleYang, L., Zheng, Y.-Z., Lin, H.-H., Chen, I.-S., Chen, K.-Y., Li, Q.-Y., & Tsai, I.-E. (2023). Under the Risk of COVID-19 Epidemic: A Study on the Influence of Life Attitudes, Leisure Sports Values, and Workplace Risk Perceptions on Urban Development and Public Well-Being. Sustainability, 15(10), 7740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107740