Urban Forest Visit Motivation Scale: Development and Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Concept of Urban Forest

2.2. Prior Studies on Motivations for Visiting Urban Forests

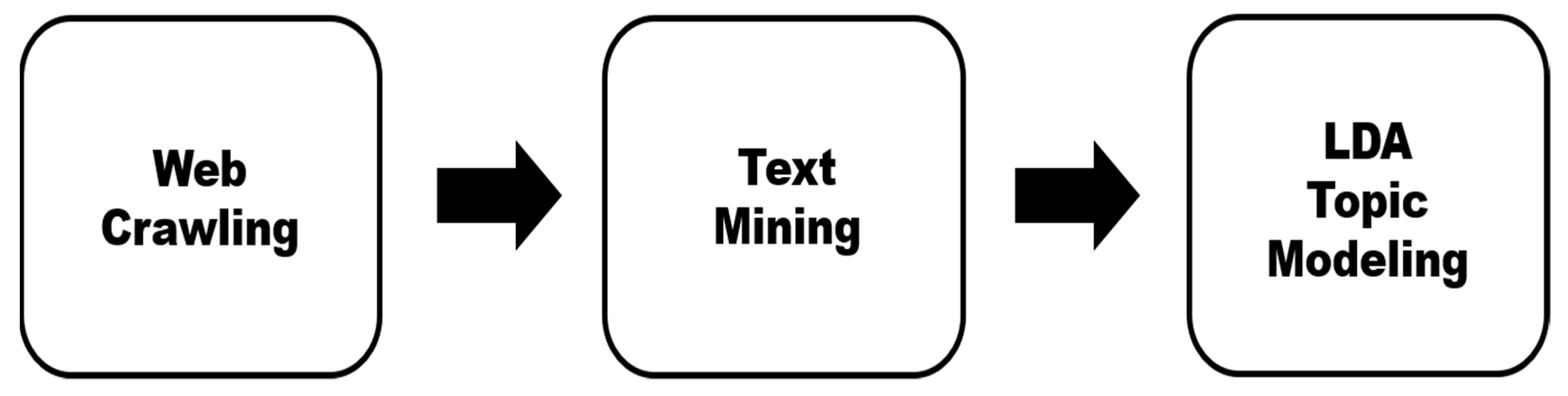

2.3. Analyzing Big Data of Motivation for Visiting Urban Forests

3. Deriving Factors of Urban Forest Visit Motivation Scale

3.1. Drawing Main Factors of UFVMS

3.1.1. Experience Activities

3.1.2. Healing and Rest

3.1.3. Health

3.1.4. Environmental Experience

3.1.5. Daily Leisure

3.1.6. Family

3.1.7. Eco-Friendly

3.2. Urban Forest Visit Motivation Scale (UFVMS): Draft Version

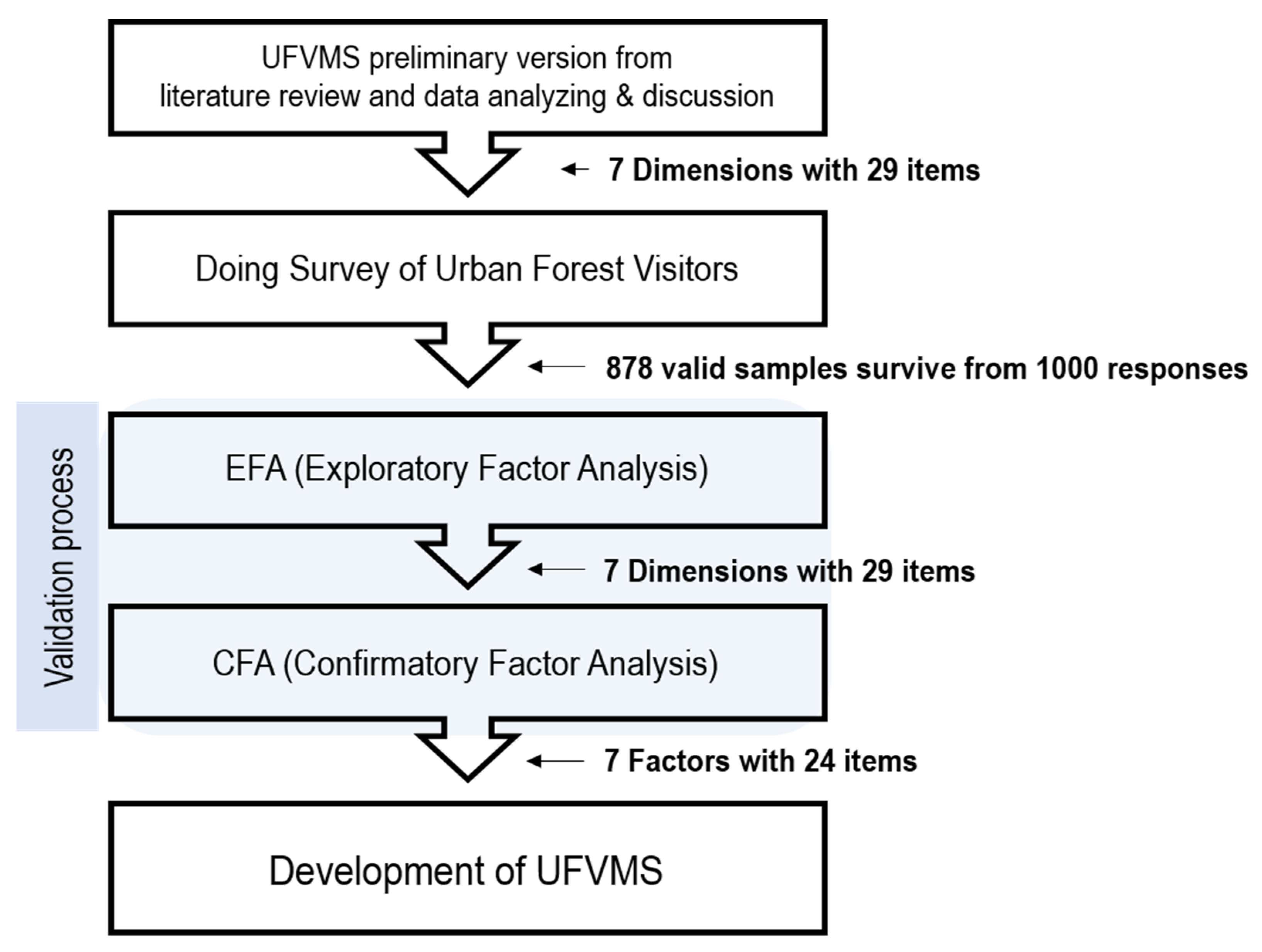

4. Methodology

4.1. A Design of Methodology

4.2. Data Collection

5. Analysis Result

5.1. Demographic Analysis

5.2. Realibility and Validity Analysis

5.2.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

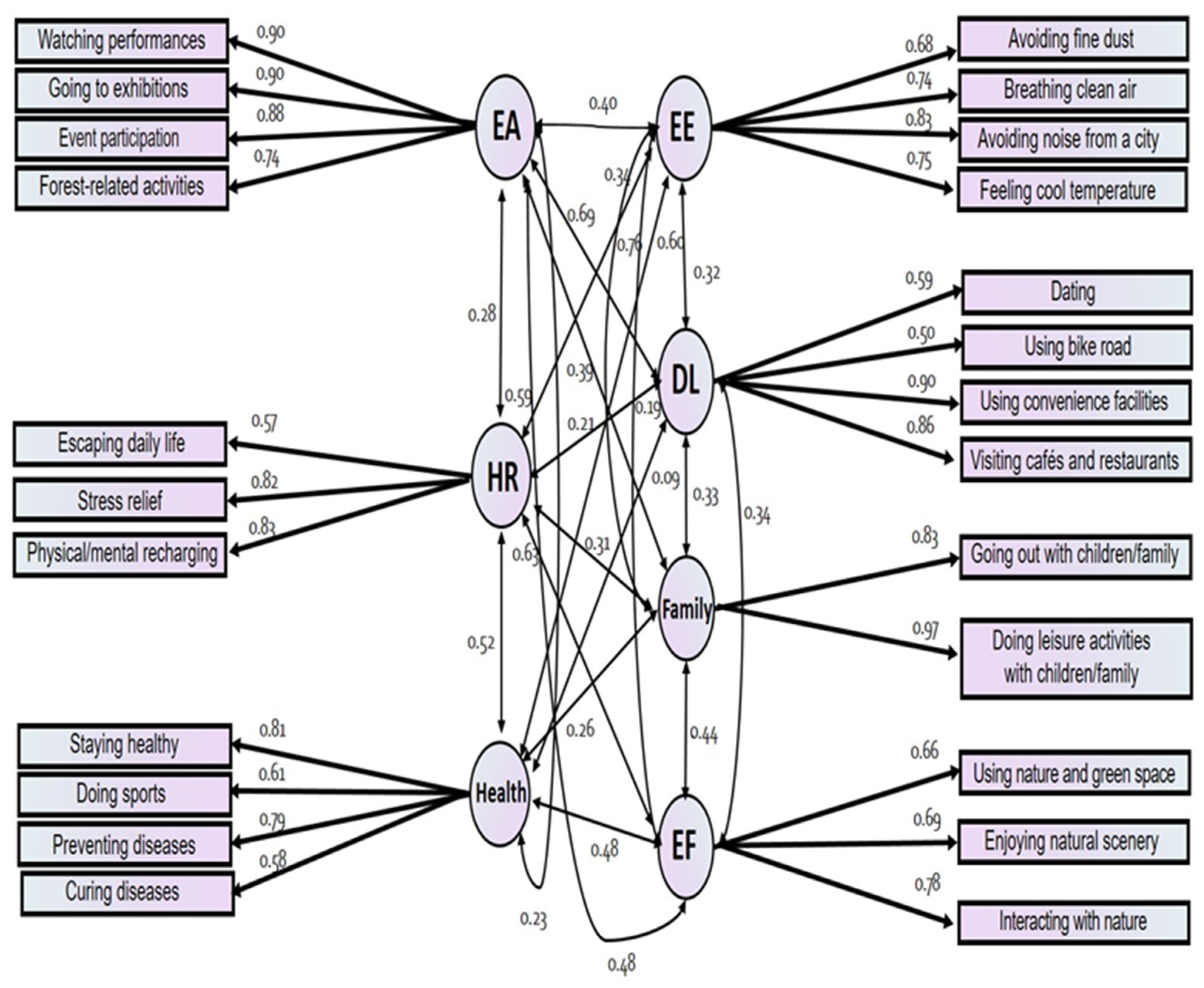

5.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

6. Conclusion and Implications

6.1. Summary of Results

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Agenda

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roy, S.; Byrne, J.; Pickering, C. A systematic quantitative review of urban tree benefits, costs, and assessment methods across cities in different climatic zones. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, K.N.; Warber, S.L.; Devine-Wright, P.; Gaston, K.J. Understanding Urban Green Space as a Health Resource: A Qualitative Comparison of Visit Motivation and Derived Effects among Park Users in Sheffield, UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Baran, P.K.; Wu, C. Spatial distributions and use patterns of user groups in urban forest parks: An examination utilizing GPS tracker. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 35, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujcic, M.; Tomicevic-Dubljevic, J. Urban forest benefits to the younger population: The case study of the city of Belgrade, Serbia. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 96, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajter Ostoić, S.; Salbitano, F.; Borelli, S.; Verlič, A. Urban forest research in the Mediterranean: A systematic review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN DESA. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Endreny, T.A. Strategically growing the urban forest will improve our world. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.J.; Kim, H.K.; Lee, T.J. Visitor motivational factors and level of satisfaction in wellness tourism: Comparison between first-time visitors and repeat visitors. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Son, Y.-H.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.K. Healing experiences of middle-aged women through an urban forest therapy program. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Crane, D.E. The Urban Forest Effects (UFORE) model: Quantifying urban forest structure and functions. Open J. For. 2000, 10, 714–720. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/research/treesearch/18420 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Tyrväinen, L.; Silvennoinen, H.; Kolehmainen, O. Ecological and aesthetic values in urban forest management. Urban For. Urban Green. 2003, 1, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Greenfield, E.J. US Urban Forest Statistics, Values, and Projections. J. For. 2018, 116, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, C.; Duinker, P.N. An analysis of urban forest management plans in Canada: Implications for urban forest management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 116, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Hoehn, R.E.I.; Bodine, A.R.; Greenfield, E.J.; Ellis, A.; Endreny, T.A.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Henry, R. Assessing Urban Forest Effects and Values: Toronto’s Urban Forest; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 1–59. [CrossRef]

- USDA Forest Service. Forest Inventory and Analysis–Fiscal Year 2020 Business Report. 2022; pp. 1–78. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/fs_media/fs_document/FS%20FIA%20Fiscal%20Year%202020%20BusinessReport_508.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Chen, K.H.; Chang, F.H.; Tung, K.X. Measuring wellness-related lifestyles for local tourists in Taiwan. Tour. Anal. 2014, 19, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.R.; Matheny, N.P.; Cross, G.; Wake, V. A model of urban forest sustainability. J. Arboric. 1997, 23, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X. Urban forest in China: Development patterns, influencing factors and research prospects. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2005, 12, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebner, D.L.; Bettinger, P.; Siry, J.P.; Boston, K. Chapter 16—Urban Forestry. In Introduction to Forestry and Natural Resources, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, B.C.; Park, K.H. Determination of Motivating Factors of Urban Forest Visitors through Latent Dirichlet Allocation Topic Modeling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home, R.; Hunziker, M.; Bauer, N. Psychosocial outcomes as motivations for visiting nearby urban green spaces. Leis. Sci. 2012, 34, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, H.; Nunes, F.; Oliveira, J.V.; Madureira, T. Preferences for urban green space characteristics: A comparative study in three Portuguese cities. Environments 2018, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, B.; Han, L.; Mei, R. The motivation and factors influencing visits to small urban parks in Shanghai, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 60, 127086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschhorn, F. Reflections on the application of the Delphi method: Lessons from a case in public transport research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2019, 22, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, L.M. Cross-sectional survey research. Medsurg. Nurs. 2016, 25, 369. Available online: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A470159876/AONE?u=anon~7b5c8f18&sid=googleScholar&xid=ee6b012c (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Burnham, T. Urban Forests in a Changing Environment: Motivations for Tree Planting and Perspectives of Climate Change Impacts on Urban Forests. 2019. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresdiss/288 (accessed on 24 September 2022).

- Kwak, D.A.; Lim, J.S.; Moon, G.H. Current Status of Domestic and Foreign Urban Forest Definition and Survey System. Korea Natl. Inst. For. Sci. 2021. Available online: http://know.nifos.go.kr/book/search/DetailView.ax?&cid=174945 (accessed on 1 October 2022). (In Korean).

- Korea Forest Service. Basic Statistics of Korea Forest. 2011, pp. 27–31. Available online: https://www.korea.kr/archive/expDocView.do?docId=31302 (accessed on 1 October 2022). (In Korean).

- Koo, J.-C.; Park, M.S.; Youn, Y.-C. Preferences of urban dwellers on urban forest recreational services in South Korea. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devisscher, T.; Ordóñez-Barona, C.; Dobbs, C.; Baptista, M.D.; Navarro, N.M.; Aguilar, L.A.O.; Perez, J.F.C.; Mancebo, Y.R.; Escobedo, F.J. Urban forest management and governance in Latin America and the Caribbean: A baseline study of stakeholder views. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 67, 127441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, F.J.; Kroeger, T.; Wagner, J.E. Urban forests and pollution mitigation: Analyzing ecosystem services and disservices. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 2078–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Urban Forest Definition. Available online: https://www.fao.org/forestry/urbanforestry/87025/en/ (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Shan, X.-Z. Socio-demographic variation in motives for visiting urban green spaces in a large Chinese city. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, E.K.; Lee, S.K. The Influences of the Tourism Motivation on the Perceived Value and Satisfaction of Healing Forest Visitor. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 29, 79–93. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE06643383 (accessed on 18 September 2022). (In Korean).

- Liu, H.; Li, F.; Xu, L.; Han, B. The impact of socio-demographic, environmental, and individual factors on urban park visitation in Beijing, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 163, S181–S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomićević, J.; Živojinović, I.; Tijanić, A. Urban forests and the needs of visitors: A case study of Košutnjak park forest, Serbia. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2017, 16, 2325–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Li, X.; Sirakaya-Turk, E. Push–Pull Dynamics in Travel Decisions. In Handbook of Hospitality Marketing Management; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2009; Volume 412, pp. 434–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Gerritsen, R. What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 10, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akehurst, G. User generated content: The use of blogs for tourism organisations and tourism consumers. Serv. Bus. 2009, 3, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet Trend. Available online: http://www.internettrend.co.kr/trendForward.tsp (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Younan, D.; Tuvblad, C.; Li, L.; Wu, J.; Lurmann, F.; Franklin, M.; Berhane, K.; McConnell, R.; Wu, A.H.; Baker, L.A. Environmental determinants of aggression in adolescents: Role of urban neighborhood greenspace. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesler, R.; Plaut, P.; Endvelt, R. The Effects of an Urban Forest Health Intervention Program on Physical Activity, Substance Abuse, Psychosomatic Symptoms, and Life Satisfaction among Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.Y.; Jim, C.Y. Resident motivations and willingness-to-pay for urban biodiversity conservation in Guangzhou (China). Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 1052–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, L.; Nordlund, A.; Olsson, O.; Westin, K. Beliefs about urban fringe forests among urban residents in Sweden. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Sun, Z.; Bao, Z. Landscape perception and recreation needs in urban green space in Fuyang, Hangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Benckendorff, P.; Gannaway, D. Learner engagement in MOOCs: Scale development and validation. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, G.L. A Study on the Effect of Forest Experience Program with Father-Child Relationship and Attitude toward the Forest. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 21 2020, 11, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Kaur, J.; Pandey, S.K.; Joshi, S. E-service Quality: Development and Validation of the Scale. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoo, F.E.; Kim, S.S.; Choi, Y. Developing a Multidimensional Measurement Scale for Diaspora Tourists’ Motivation. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xia, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, W.; Wang, S. Crowd Logistics Platform’s Informative Support to Logistics Performance: Scale Development and Empirical Examination. Sustainability 2019, 11, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.C. A Review of Exploratory Factor Analysis Decisions and Overview of Current Practices: What We Are Doing and How Can We Improve? Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2016, 32, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson, G.D.; Sofroniou, N. The Multivariate Social Scientist: Introductory Statistics Using Generalized Linear Models; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometrictheory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Balkan-Kiyici, F.; Topaloäžlu, M.Y. A scale development study for the teachers on out of school learning environments. MOJES Malays. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2018, 4, 1–13. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1116317.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, J.; Chahal, H.; Gupta, M. Re-Investigating Market Orientation and Environmental Turbulence in Marketing Capability and Business Performance Linkage: A Structural Approach. In Understanding the Role of Business Analytics; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Li, Z. Research on The Influent Factors of Relationship Performance by An Intrinsic Incentive Growth Model for Chinese Universities’ Teachers. Psychol. Educ. J. 2021, 58, 910–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2009, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Análise Multivariada de Dados; Bookman Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lamm, K.W.; Lamm, A.J.; Edgar, D.W. Scale development and validation: Methodology and recommendations. J. Int. Agric. Ext. Educ. 2020, 27, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.M.; Rudd, J.M. Factor analysis and discriminant validity: A brief review of some practical issues. In Proceedings of the Anzmac, Melbourne, Australia, 30 November–2 December 2009; Available online: https://research.aston.ac.uk/en/publications/factor-analysis-and-discriminant-validity-a-brief-review-of-some (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- United Nations. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2018-KeyFacts.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Livesley, S.J.; McPherson, E.G.; Calfapietra, C. The urban forest and ecosystem services: Impacts on urban water, heat, and pollution cycles at the tree, street, and city scale. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, K.J.; Clarkson, B.D. Urban forest restoration ecology: A review from Hamilton, New Zealand. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2019, 49, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberger, A. Recreation use of urban forests: An inter-area comparison. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 4, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesler, R.; Endevelt, R.; Plaut, P. Urban Forest Health Intervention Program to promote physical activity, healthy eating, self-efficacy and life satisfaction: Impact on Israeli at-risk youth. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daab145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudi, B.; Sorouri, Z.; Zenner, E.K.; Mafi-Gholami, D. Development of a new social resilience assessment model for urban forest parks. Environ. Dev. 2022, 43, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Definition of an Urban Forest | Ref. |

|---|---|

| Urban parks, planted green places, nature remnants, natural forests and woodlots in urban or peri-urban area (including some kinds of private garden, green roof, farm, and so on) | [30] |

| The sum of all urban trees, shrubs, lawns, and pervious soils located in highly altered and extremely complex ecosystems where humans are the main drivers of their types, amounts, and distribution | [31] |

| Networks or systems comprising all woodlands, groups of trees, and individual trees located in urban and peri-urban areas | [32] |

| Publicly and privately owned trees within an urban area, which include individual trees along streets and in backyards, as well as stands of remnant forests | [27] |

| Trees and other vegetation growing along streets and waterways, around buildings, in backyards, and parks of our cities and towns | [15] |

| Motivating Factors | Type of Urban Forest | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Time with children, Nordic walking, cycling, walking, dog walking, jogging, reading, picnicking, ball games, passive games | Urban green space | [21] |

| Physical, space qualities, children, cognitive, social and unstructured time | [2] | |

| Fresh air/scenery, relaxation, exercise, quietness, contacting nature, playing with children, social interaction, accompanying the elderly, walking pets, watching wildlife, cultural activities, adventure, others | [33] | |

| Relaxation and rest, physical exercise, meeting friends, taking children out, walking, nature or clean air, others | [23] | |

| Physical motivation, psychological motivation, social motivation, natural environment, facilities, programs, and experiences and activities | Urban healing forest | [34] |

| Physical exercise, relaxation and rest, interactions with nature, taking children out, enjoying cool weather, visiting cultural sites, fresh and clean air, reading a book, walking the dog | Urban forest park | [35] |

| Active recreation, walking, having fun, relaxing, others | [36] | |

| Contact with nature and relax, lay with children, get together with families and friends, jogging/walking, picnic, barbeque, boating, exercise, others | [3] | |

| Café-related walk, daily leisure, clean space, exhibition and photography, healing trip, family, wonderful view | Urban forest | [20] |

| Topic | Events | Date/Stroll | Trip | Scenery of Nature | Cafe | Outing | Family Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranks | Name | Name | Name | Name | Name | Name | Name |

| 1 | Festival | Road | Travel destination | Tourism | Fall | Fine dust | Lake |

| 2 | Trip | Tree | Recommendation | Picture | Travel | Museum | Children |

| 3 | Region | People | Mountain | River | Tea | Lake | Scenery |

| 4 | Fall | Trip | Pine tree | Location | Lake | Dog | Camping site |

| 5 | Lake | Street | Travel | Winter | Planning | Nature | Experience |

| 6 | Program | Love | Road | Ocean | Café | Convenience store | Trip |

| 7 | Attractiveness | Course | Time | People | Mountain | Tree | Camping |

| Dimensions | Measurement Items | Short Word | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experience Activities (EA) | To take pictures of the scenery of/around an urban forest | Taking pictures of scenery | [20,33,34,35,36] |

| To experience various forest-related experience activities | Forest-related experience | ||

| To watch festivals and performances in an urban forest | Watching performances | ||

| To go to a small exhibition in an urban forest | Going to an exhibition | ||

| To participate in various events in an urban forest | Participating events | ||

| Healing and Rest (HR) | To spend time in nature | Spending time in nature | [20,23,33,34,35,36] |

| To get out of one’s boring daily life | Out of boring life | ||

| To relieve stress | Relieving stress | ||

| for physical/mental recharging | Recharging | ||

| Health | for taking a walk | Taking a walk | [2,20,21,23, 34,35,42] |

| To participate in a program for health and healing (e.g., meditation/walking, etc.) | Program for health | ||

| To engage in simple sports | Simple sports | ||

| To stay healthy | Staying healthy | ||

| To prevent diseases | Preventing diseases | ||

| To cure diseases | Curing diseases | ||

| Environmental Experience (EE) | To avoid fine dust | Avoiding dust | [14,20,23,33,34,35] |

| To breathe clean air | Clean air | ||

| To avoid noise in the city | Avoiding noise | ||

| To feel the cool temperature (To get out of the heat island phenomenon) | Cool temperature | ||

| Daily Leisure (DL) | To visit famous cafes and restaurants in the urban forest | Cafes and restaurants | [2,3,20,21,23,33,34] |

| To use the convenience facilities within the urban forest | Convenience facilities | ||

| For a date with the opposite sex | Dating | ||

| To use the bike road | Bike road | ||

| To take a walk with one’s dog | Walking with a dog | ||

| Family | To go out with children/family | Go out with family | [2,20,21,23,33,35] |

| To do various leisure with children/family | Various leisure with family | ||

| Eco-Friendly (EF) | To enjoy the natural scenery around the city forest | Enjoy scenery | [23,33,34,35] |

| To use the nature and green space in an urban forest | Using green space | ||

| To interact with nature (e.g., animals, trees, plants, etc.) | Interact with nature |

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) | Characteristic | Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 431 (49.1) | Income ($) | <200 | 82 (9.3) |

| Male | 447 (50.9) | ||||

| Marital status | Married | 524(59.7) | Equal to or greater than 200, and <400 | 242 (27.6) | |

| Unmarried | 338 (38.5) | ||||

| Age | Less than 20 | 49 (5.6) | Equal to or greater than 400, and <600 | 271 (30.9) | |

| 20–39 | 327 (37.2) | ||||

| 40–59 | 354 (40.3) | ||||

| Above 60 | 148 (16.9) | Equal to or greater than 600 | 283 (32.2) | ||

| Education level | Below high school graduate | 34 (3.9) | |||

| High school graduate | 213 (24.3) | ||||

| University graduate | 519 (59.1) | Job | Office/technical | 347 (39.5) | |

| Professional | 90 (10.3) | ||||

| Greater than or equal to graduate school | 34 (3.9) | Self-owned | 43 (4.9) | ||

| Sales/service | 56 (6.4) | ||||

| Freelancer | 14 (1.6) | ||||

| Student | 119 (13.6) | ||||

| Others | 19 (2.2) | ||||

| Unemployed | 190 (21.6) | ||||

| Total | 878 (100.0) | Total | 878 (100.0) | ||

| Dimensions | Factors (Variables) | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α (Variance) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experience Activities (5) | To watch festivals and performances in an urban forest | 0.847 | 0.894 (13.057) |

| To go to a small exhibition in an urban forest | 0.834 | ||

| To participate in various events in an urban forest | 0.830 | ||

| To experience various forest-related experience activities | 0.669 | ||

| To take pictures of the scenery of/around an urban forest | 0.449 | ||

| Healing and Rest (5) | To get out of the boring daily life | 0.759 | 0.878 (11.245) |

| To relieve stress | 0.739 | ||

| For physical/mental recharging | 0.720 | ||

| To spend time in nature | 0.631 | ||

| Health (6) | To stay healthy | 0.810 | 0.826 (10.598) |

| To engage in simple sports | 0.787 | ||

| To prevent diseases | 0.745 | ||

| To cure diseases | 0.609 | ||

| To participate in programs for health and healing (e.g., meditation/walking, etc.) | 0.501 | ||

| For taking a walk | 0.485 | ||

| Environmental Experience (4) | To avoid fine dust | 0.764 | 0.816 (10.063) |

| To breathe clean air | 0.738 | ||

| To avoid noise in the city | 0.738 | ||

| To feel the cool temperature (to get out of the heat island phenomenon) | 0.615 | ||

| Daily Leisure (5) | For a date with the opposite sex | 0.771 | 0.845 (9.478) |

| To use bike roads | 0.720 | ||

| To take a walk with one’s dog | 0.720 | ||

| To use convenience facilities within the urban forest | 0.599 | ||

| To visit famous cafes and restaurants in the urban forest | 0.590 | ||

| Family (2) | To go out with children/family | 0.868 | 0.794 (5.580) |

| To do various leisure activities with children/family | 0.796 | ||

| Eco-Friendly (3) | To use the nature and green space in an urban forest | 0.765 | 0.791 (7.179) |

| To enjoy the natural scenery around the city forest | 0.745 | ||

| To interact with nature (e.g., animals, trees, plants, etc.) | 0.570 |

| Measurement Variables | R.W. | S.E. | C.R. | S.R.W. | C.R. | A.V.E. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience Activities | Watching performances | 1.000 | - | - | 0.899 | 0.917 | 0.736 |

| Going to exhibitions | 1.019 | 0.027 | 37.735 | 0.904 | |||

| Event participation | 0.981 | 0.027 | 35.985 | 0.882 | |||

| Forest-related activities | 0.838 | 0.031 | 26.735 | 0.735 | |||

| Healing & Rest | Escaping daily life | 1.000 | - | - | 0.566 | 0.789 | 0.562 |

| Stress relief | 1.294 | 0.080 | 16.259 | 0.822 | |||

| Physical/mental recharging | 1.202 | 0.076 | 15.746 | 0.831 | |||

| Health | Staying healthy | 1.000 | - | - | 0.818 | 0.795 | 0.498 |

| Doing sports | 0.834 | 0.044 | 19.024 | 0.610 | |||

| Preventing diseases | 1.128 | 0.071 | 15.858 | 0.785 | |||

| Curing diseases | 0.826 | 0.072 | 11.424 | 0.578 | |||

| Environmental Experience | Avoiding fine dust | 1.000 | - | - | 0.681 | 0.838 | 0.566 |

| Breathing clean air | 0.998 | 0.046 | 21.936 | 0.745 | |||

| Avoiding noise from a city | 1.198 | 0.059 | 20.316 | 0.825 | |||

| Feeling cool temperature | 0.943 | 0.051 | 18.474 | 0.752 | |||

| Daily Leisure | Dating | 1.000 | - | - | 0.589 | 0.814 | 0.536 |

| Using bike road | 0.834 | 0.053 | 15.704 | 0.503 | |||

| Using convenience facilities | 1.356 | 0.074 | 18.434 | 0.900 | |||

| Visiting cafés and restaurants | 1.317 | 0.072 | 18.255 | 0.857 | |||

| Family | Going out with children/family | 1.000 | - | - | 0.833 | 0.901 | 0.821 |

| Doing leisure activities with children/family | 1.087 | 0.056 | 19.542 | 0.973 | |||

| Eco-Friendly | Using nature and green space | 1.000 | - | - | 0.661 | 0.754 | 0.506 |

| Enjoying natural scenery | 1.121 | 0.053 | 21.008 | 0.694 | |||

| Interacting with nature | 1.470 | 0.087 | 16.867 | 0.775 | |||

| AVE | EA | EE | HR | DL | Health | Family | EF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA | 0.736 | 0.858 | ||||||

| EE | 0.566 | 0.396 *** | 0.752 | |||||

| HR | 0.562 | 0.277 *** | 0.588 *** | 0.750 | ||||

| DL | 0.536 | 0.685 *** | 0.319 *** | 0.212 *** | 0.732 | |||

| Health | 0.498 | 0.235 *** | 0.600 *** | 0.517 *** | 0.091 * | 0.706 | ||

| Family | 0.821 | 0.386 *** | 0.328 *** | 0.309 *** | 0.321 *** | 0.258 *** | 0.906 | |

| EF | 0.506 | 0.476 *** | 0.756 *** | 0.629 *** | 0.345 *** | 0.485 *** | 0.440 *** | 0.712 |

| Urban Forest Visit Motivation Scale (UFVMS) (Seven Dimensions with 24 Factors) | |

|---|---|

| Experience Activities | Watching performances |

| Going to exhibitions | |

| Event participation | |

| Forest-related activities | |

| Healing and Rest | Escaping daily life |

| Stress relief | |

| Physical/mental recharging | |

| Health | Staying healthy |

| Doing sports | |

| Preventing diseases | |

| Curing diseases | |

| Environmental Experience | Avoiding fine dust |

| Breathing clean air | |

| Avoiding noise from a city | |

| Feeling cool temperature | |

| Daily Leisure | Dating with opposite sex |

| Using bike road | |

| Using convenience facilities | |

| Visiting cafés and restaurants | |

| Family | Going out with children/family |

| Doing leisure activities with children/family | |

| Eco-Friendly | Using nature and green space |

| Enjoying natural scenery | |

| Interacting with nature | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.; Kim, D.-H. Urban Forest Visit Motivation Scale: Development and Validation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010408

Lee J, Kim D-H. Urban Forest Visit Motivation Scale: Development and Validation. Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010408

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jun, and Dong-Han Kim. 2023. "Urban Forest Visit Motivation Scale: Development and Validation" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010408

APA StyleLee, J., & Kim, D.-H. (2023). Urban Forest Visit Motivation Scale: Development and Validation. Sustainability, 15(1), 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010408