A Systematic Review of the Development of Sport Policy Research (2000–2020)

Abstract

1. Introduction

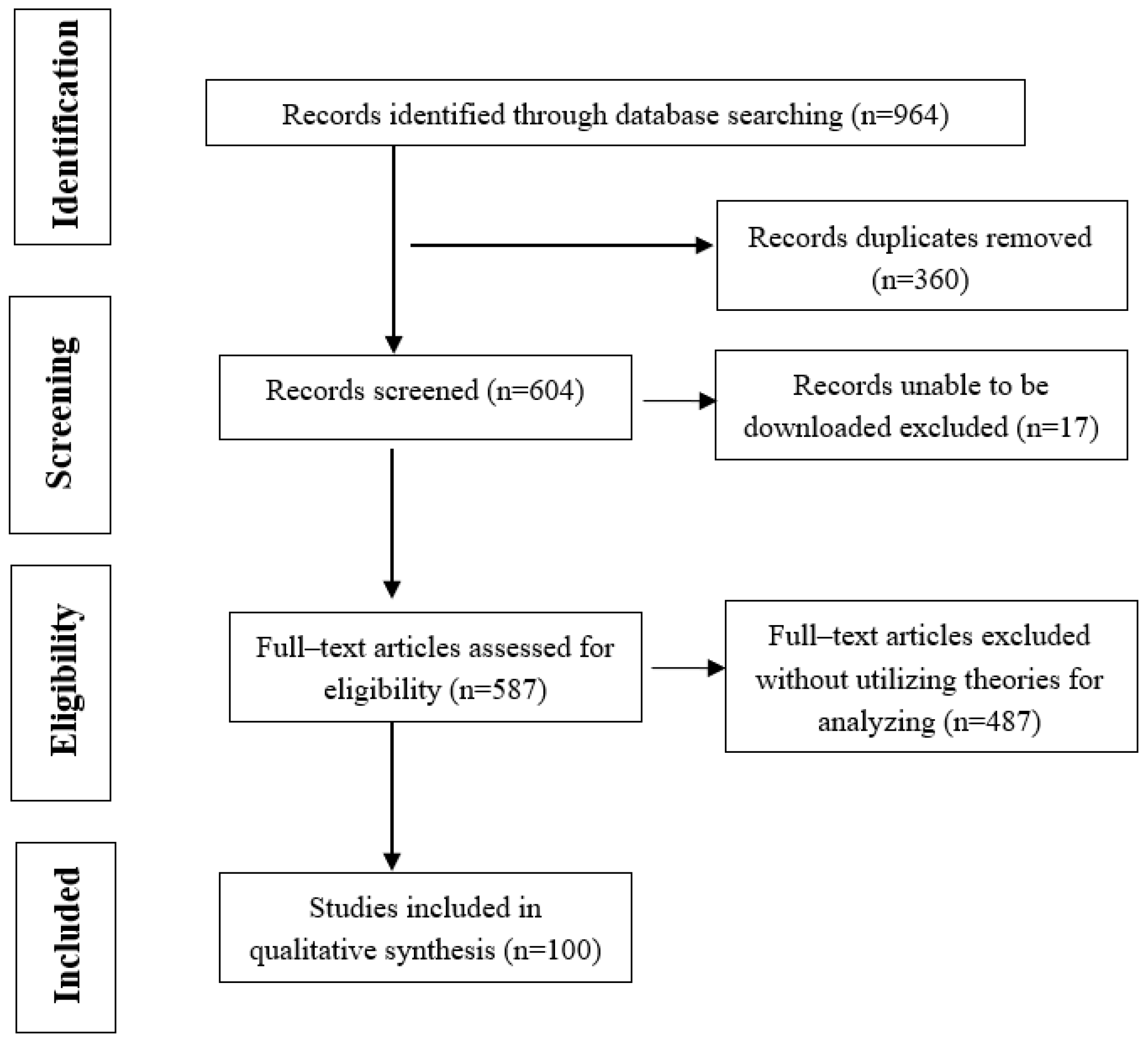

2. Methods

2.1. Research Protocol

2.2. Research Trustworthiness

2.3. Research Scopes and Limitations

3. Results

| Policy Type | Theory | Included Papers | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elite sport | 1. Foucault’s governmentality | Piggin, Jackson and Lewis (2009) [76] | 1 |

| 2. Institutional theory/Neo–institutionalism | Vos, Breesch, Késenne, Van Hoecke, Vanreusel, and Scheerder (2011) * [77] | 1 | |

| 3. Path dependency | Houlihan (2009) [78]; Park, Lim, and Bretherton (2012) [28] | 2 | |

| 4. Resource dependence theory | Giannoulakis, Papadimitriou, Alexandris, and Brgoch (2017) [79]; Vos, Breesch, Késenne, Van Hoecke, Vanreusel, and Scheerder (2011) * [77]; Vos, Wicker, Breuer, and Scheerder (2013) [80] | 3 | |

| Sport for all | 1. Institutional theory/Neo–institutionalism | Skille (2009) [81] | 1 |

| Multi–type | 1. Path dependency | Green and Collins (2008) [82] | 1 |

| Non–specified | 1. Institutional theory/Neo–institutionalism | Houlihan (2005) * [11] | 1 |

| Total | 10 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shao, Y.L. Sports drive personal and national competitiveness. Phys. Educ. Sch. 2015, 147, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (2020). Sport and Anti–Doping. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/sport–and–anti–doping (accessed on 4 July 2020).

- Liston, K.; Gregg, R.; Lowther, J. Elite sports policy and coaching at the coalface. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2013, 5, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Cashore, B. Conceptualizing Public Policy. In Comparative Policy Studies; Engeli, I., Allison, C.R., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M. Public Policy; Chiguang: Tainan, Taiwan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.J. Public Policy Analysis: An Introduction; Liwen: Taipei, Taiwan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.J.; Chiu, J.S. The Policy Changes in Physical Education and Sport in Taiwan; Fardu: Taipei, Taiwan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan, B. Introduction: Government and Civil Society Involvement in Sports Development. In Routledge Handbook of Sports Development; Houlihan, B., Green, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan, B.; Bloyce, D.; Smith, A. Developing the research agenda in sport policy. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2009, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.C.; Su, W.S. An analysis of topics and trends in sport management research. J. Sport Recreat. Manag. 2011, 8, 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan, B. Public sector sport policy: Developing a framework for analysis. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2005, 40, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.P.; Chang, C.; Ni, Y.L. Sport management: Current status and trend analysis. Phys. Educ. J. 2012, 45, 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Foresight and Innovation Policies. Fundamental Science and Technology Act. 2020. Available online: https://law.most.gov.tw/LawContent.aspx?id=FL009566 (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Sotiriadou, P.; Gowthorp, L.; De Bosscher, V. Elite sport culture and policy interrelationships: The case of Sprint Canoe in Australia. Leis. Stud. 2014, 33, 598–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, M.; Scelles, N.; Morrow, S. Elite sport policies and international sporting success: A panel data analysis of European women’s national football team performance. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 20, 300–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlihan, B. Theorizing the analysis of sport policy. In Routledge Handbook of Sport Policy; Henry, I., Ko, L.M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2014; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, I.; Ko, L.M. Analysing sport policy in a globalizing context. In Routledge Handbook of Sport Policy; Henry, I., Ko, L.M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2014; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.C. An Introduction and suggestion on systematic review and meta–analysis in domestic education. J. Educ. Stud. 2010, 44, 133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta–analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M. Changing policy priorities for sport in England: The emergence of elite sport development as a key policy concern. Leis. Stud. 2004, 23, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bosscher, V.; Shibli, S.; Van Bottenburg, M.; De Knop, P.; Truyens, J. Developing a method for comparing the elite sport systems and policies of nations: A mixed research methods approach. J. Sport Manag. 2010, 24, 567–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, L.M. A systematic review of the literature on management competencies in the sport industry. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Knowledge–Based Economy & Global Management, Tainan, Taiwan, 2–6 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.Y.; Yeh, M.K. Overview the methods of systematic review and meta–analysis. J. Taiwan Pharm. 2018, 34, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.K.; Wang, C.H. Validity and reliability of qualitative research in education. J. Educ. Natl. Chang. Univ. Educ. 2010, 17, 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, L.C.; Huang, K.H. Methods of qualitative data analysis in physical education and sport studies. Phys. Educ. J. 2014, 47, 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.W.; Lim, S.Y.; Bretherton, P. Exploring the Truth: A Critical Approach to the Success of Korean Elite sport. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2012, 36, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker–Ruchti, N.; Schubring, A.; Aarresola, O.; Kerr, R.; Grahn, K.; McMahon, J. Producing success: A critical analysis of athlete development governance in six countries. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2018, 10, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P. The Governance of Sport in Australia: Centralization, Politics and Public Diplomacy, 1860–2000. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2015, 32, 1238–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlihan, B.; Zheng, J. Small states: Sport and politics at the margin. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2015, 7, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, C.P. National recognition and power relations between states and sub–state governments in international sport. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2020, 12, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.R. Managing the Mega–Event ‘Habit’: Canada as serial user. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2017, 9, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M. Integrating Macro– and Meso–Level Approaches: A Comparative Analysis of Elite Sport Development in Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2005, 5, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henne, K.; Pape, M. Dilemmas of Gender and Global Sports Governance: An Invitation to Southern Theory. Sociol. Sport J. 2018, 35, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Davies, B. Physical Education PLC: Neoliberalism, curriculum and governance. New directions for PESP research. Sport Educ. Soc. 2014, 19, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D. Like a Fish in Water: Physical Education Policy and Practice in the Era of Neoliberal Globalization. Quest 2011, 63, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D. Assembling the privatisation of physical education and the ‘inexpert’ teacher. Sport Educ. Soc. 2015, 20, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, F.; Flintoff, A. A whitewashed curriculum? The construction of race in contemporary PE curriculum policy. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, C. Sex, sport and justice: Reframing the ‘who’ of citizenship and the ‘what’ of justice in European and UK sport policy. Sport Educ. Soc. 2016, 21, 1193–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, C. Sex, sport and money: Voice, choice and distributive justice in England, Scotland and Wales. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 23, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, M.; Safai, P. Innovating Canadian sport policy: Towards new public management and public entrepreneurship? Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2020, 12, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, H.K.; Fuchs, A. From corporatism to open networks? Structural changes in German sport policy-making. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2014, 6, 327–348. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.; Houlihan, B. Advocacy Coalitions and Elite Sport Policy Change in Canada and the United Kingdom. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2004, 39, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.R. Ideological conflicts behind mutual belief: The termination of the ‘dual-registration policy’and the collapse of an effective elite diving system in China. Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 1362–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, R. ‘Managing change’ in British tennis 1990–2006: Unintended outcomes of LTA talent development policies. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2010, 45, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grix, J. The impact of UK sport policy on the governance of athletics. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2009, 1, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, P.; Piggin, J.; Mezzadri, F. The politics of sport funding in Brazil: A multiple streams analysis. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2020, 12, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, P. An analysis of Glasgow’s decision to bid for the 2014 Commonwealth Games. Sport Soc. 2017, 20, 1870–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadou, P.; Brouwers, J. A critical analysis of the impact of the Beijing Olympic Games on Australia’s sport policy direction. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2012, 4, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Liu, D. The ‘30–gold’ ambition and Japan’s momentum for elite sport success: Feasibility and policy changes. Sport Soc. 2020, 23, 1964–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, R.; Obel, C.; Wang, B. Reassembling sex: Reconsidering sex segregation policies in sport. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2018, 10, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viollet, B.; Scelles, N.; Ferrand, A. The engagement of actors during the formulation of a national federation sport policy: An analysis within the French Rugby Union. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2020, 12, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlihan, B.; Green, M. The changing status of school sport and physical education: Explaining policy change. Sport Educ. Soc. 2006, 11, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillpots, L. An analysis of the policy process for physical education and school sport: The rise and demise of school sport partnerships. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2013, 5, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, D.; Kumar, S. Physical Education, Citizenship, and Social Justice: A Position Statement. Quest 2019, 71, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, G.; Thorburn, M. Analysing policy change in Scottish physical education and school sport. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2011, 3, 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlenbrock, C.; Meier, H.E. Public–private partnerships in physical education: The catalyst for UNESCO’s Quality Physical Education (QPE) Guidelines. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 26, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, M.; Hogan, A.; Enright, E. Youth sport policy: The enactment and possibilities of ‘soft policy’ in schools. Sport Educ. Soc. 2019, 24, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, A. Analysing policy change and continuity: Physical education and school sport policy in England since 2010. Sport Educ. Soc. 2020, 25, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlén, J.; Skille, A. State sport policy for indigenous sport: Inclusive ambitions and exclusive coalitions. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2017, 9, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skille, E.Å. Understanding Sport Clubs as Sport Policy Implementers: A Theoretical Framework for the Analysis of the Implementation of Central Sport Policy through Local and Voluntary Sport Organizations. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2008, 43, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsard, N.A.; Borodulin, K.; Fahlen, J.; Høyer–Kruse, J.; Iversen, E.B. National structures for building and managing sport facilities: A comparative analysis of the Nordic countries. Sport Soc. 2019, 22, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlén, J.; Eliasson, I.; Wickman, K. Resisting self–regulation: An analysis of sport policy programme making and implementation in Sweden. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2015, 7, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbels, L.; Voets, J.; Marlier, M.; De Waegeneer, E.; Willem, A. Why network structure and coordination matter: A social network analysis of sport for disadvantaged people. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2018, 53, 572–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M. Olympic glory or grassroots development? Sport policy priorities in Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom, 1960–2006. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2007, 24, 921–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M. Podium or participation? Analysing policy priorities under changing modes of sport governance in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2009, 1, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grix, J. The ‘governance debate’ and the study of sport policy. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2010, 2, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grix, J.; Phillpots, L. Revisiting the ‘Governance Narrative’—‘Asymmetrical Network Governance’ and the deviant case of the sports policy sector. Public Policy Adm. 2011, 26, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fahlén, J.; Steling, C. Sport policy in Sweden. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2016, 8, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillpots, L.; Grix, J.; Quarmby, T. Centralized grassroots sport policy and ‘new governance’: A case study of county sports partnerships in the UK—Unpacking the paradox. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2010, 46, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Guett, M. Fragmented, complex and cumbersome: A study of disability sport policy and provision in Europe. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2014, 6, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, S. Advancing our understanding of the EU sports policy: The socio–cultural model of sports regulation and players’ agents. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2018, 10, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, K.; Chepyator-Thomson, J.R. Sports policy in Kenya: Deconstruction of colonial and post–colonial conditions. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2015, 7, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.C. The Transformation of China’s National Fitness Policy: From a Major Sports Country to a World Sports Power. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2015, 32, 1071–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggin, J.; Jackson, S.J.; Lewis, J. Knowledge, Power and Politics—Contesting “Evidence–based” National Sport Policy. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2009, 44, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, S.; Breesch, D.; Késenne, S.; Van Hoecke, J.; Vanreusel, B.; Scheerder, J. Governmental subsidies and coercive pressures. Evidence from sport clubs and their resource dependencies. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2011, 8, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlihan, B. Mechanisms of international influence on domestic elite sport policy. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2009, 1, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Giannoulakis, C.; Papadimitriou, D.; Alexandris, K.; Brgoch, S. Impact of austerity measures on National Sport Federations: Evidence from Greece. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2017, 17, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, S.; Wicker, P.; Breuer, C.; Scheerder, J. Sports policy systems in regulated Rhineland welfare states: Similarities and differences in financial structures of sports clubs. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2013, 5, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skille, E. State Sport Policy and Voluntary Sport Clubs: The Case of the Norwegian Sports City Program as Social Policy. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2009, 9, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.; Collins, S. Policy, Politics and Path Dependency: Sport Development in Australia and Finland. Sport Manag. Rev. 2008, 11, 225–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlihan, B. Sport and International Politics; Harvester Wheatshea: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, A.J.; Withers, M.C.; Collins, B.J. Resource dependence theory: A review. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truyens, J.; De Bosscher, V.; Sortiriadou, P. An Analysis of Countries’ Organizational Resources, Capacities, and Resource Configurations in Athletics. J. Sport Manag. 2016, 30, 566–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bosscher, V. A mixed methods approach to compare elite sport policies of nations. A critical reflection on the use of composite indicators in the SPLISS study. Sport Soc. 2018, 21, 331–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Dai, J.; Wang, B. Bribing referees: The history of unspoken rules in Chinese professional football leagues, 1998–2009. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2019, 19, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bosscher, V.; Shilbury, D.; Theeboom, M.; Van Hoecke, J.; De Knop, P. Effectiveness of national elite sport policies: A multidimensional approach applied to the case of Flanders. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2011, 11, 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, I.; Dowling, M.; Ko, L.M.; Brown, P. Challenging the new orthodoxy: A critique of SPLISS and variable–oriented approaches to comparing sporting nations. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 20, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padadimitriou, D.; Alexandris, K. ‘Adopt an athlete for Rio 2016’: The impact of austerity on the Greek elite sport system. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2018, 10, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patatas, J.M.; De Bosscher, V.; Legg, D. Understanding parasport: An analysis of the differences between able–bodied and parasport from a sport policy perspective. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2018, 10, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truyens, J.; De Bosscher, V.; Heyndel, B.; Westerbeek, H. A resource–based perspective on countries’ competitive advantage in elite athletics. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2014, 6, 459–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; Hill, S.; Barwood, D.; Penney, D. Physical literacy and policy alignment in sport and education in Australia. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 27, 328–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekman, R.; Breedveld, K.; Kraaykamp, G. Providing for the rich? The effect of public investments in sport on sport (club) participation of vulnerable youth and adults. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2017, 14, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skille, E.A. Community and sport in Norway: Between state sport policy and local sport clubs. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2015, 7, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janemalm, L.; Quennerstedt, M.; Barker, D. What is complex in complex movement? A discourse analysis of conceptualizations of movement in the Swedish physical education curriculum. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 1146–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, F. A critical discourse analysis of a local enactment of sport for integration policy: Helping young refugees or self–help for voluntary sports clubs? Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2020, 55, 1152–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electronic Journal | Numbers | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Communication & Sport | 0 | 31 January 2021 |

| European Journal for Sport and Society | 3 | 31 January 2021 |

| European Physical Education Review | 4 | 31 January 2021 |

| European Sport Management Quarterly | 13 | 3 February 2021 |

| International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics | 33 | 20 February 2021 |

| International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship | 0 | 28 February 2021 |

| International Review for the Sociology of Sport | 10 | 1 March 2021 |

| Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport & Tourism Education | 0 | 1 March 2021 |

| Journal of Policy Research in Tourism Leisure and Events | 1 | 3 March 2021 |

| Journal of Sport and Social Issues | 1 | 3 March 2021 |

| Journal of Sport Management | 3 | 9 March 2021 |

| Journal of Sports Economics | 0 | 9 March 2021 |

| Kinesiology | 0 | 9 March 2021 |

| Leisure Sciences | 1 | 12 March 2021 |

| Leisure Studies | 1 | 12 March 2021 |

| Public Policy and Administration | 1 | 12 March 2021 |

| Quest | 2 | 12 March 2021 |

| Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport | 0 | 23 March 2021 |

| Sociology of Sport Journal | 3 | 23 March 2021 |

| Sport History Review | 0 | 30 March 2021 |

| Sport in Society | 8 | 1 April 2021 |

| Sport Management Review | 1 | 3 April 2021 |

| Sport, Education and Society | 11 | 3 April 2021 |

| The International Journal of the History of Sport | 4 | 4 April 2021 |

| Total | 100 |

| Policy Type | Theory | Included Papers | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elite sport | 1. Confucianism | Park, Lim, and Bretherton (2012) * [28] | 1 |

| 2. Governance | Barker–Ruchti, Schubring, Aarresola, Kerr, Grahn, and McMahon (2018) [29]; Horton (2015) [30] | 2 | |

| 3. International relations theory | Houlihan and Zheng (2015) [31]; Méndez (2020) [32] | 2 | |

| 4. Neoliberalism | Black (2017) [33]; Sturm and Rinehart (2019) | 2 | |

| 5. Neo–pluralism | Green (2005) * [34] | 1 | |

| 6. Southern theory | Henne and Pape (2018) [35] | 1 | |

| Physical education | 1. Neoliberalism | Evans and Davies (2014) [36]; Macdonald (2011) [37]; Powell (2015) [38] | 3 |

| 2. Racialization | Dowling and Flintoff (2018) [39] | 1 | |

| Sport for all | 0 | ||

| Non–specified | 1. Feminism | Devine (2016) [40]; Devin (2018) [41] | 2 |

| 2. Neo–corporatism | Meier and Fuchs (2014) * [39] | 1 | |

| 3. New public management | McSweeney and Safai (2020) * [42] | 1 | |

| 4. Public entrepreneurship | McSweeney and Safai (2020) * [42] | 1 | |

| Total | 18 |

| Policy Type | Theory | Included Papers | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elite sport | 1. Advocacy coalition framework | Green (2005) * [34]; Green and Houlihan (2004) [44]; Hu (2019) [45]; Yiamaz (2018) | 4 |

| 2. Clientelism | Enjorlas and Waldahl (2007) * | 1 | |

| 3. Corporatism | Enjorlas and Waldahl (2007) * | 1 | |

| 4. Game models | Hanstad and Skille (2008); Lake (2010) [46] | 2 | |

| 5. Habermas’s deliberate democracy theory | Kihl, Kikulis, and Thibault (2007) | 1 | |

| 6. Governance | Grix (2009) [47]; Ma and Kurscheidt (2019); | 2 | |

| 7. Institutional theory/Neo–institutionalism | Strittmatter (2016); Strittmatter and Skille (2017) | 2 | |

| 8. Matland’s model of conflict and ambiguity | O’Gorman (2011) | 1 | |

| 9. Multiple streams framework | Camargo, Piggin, and Mezzadri (2020) [48]; Salisbury (2017) [49]; Sotiriadou and Brouwers (2012) [50]; Zheng and Liu (2020) [51] | 4 | |

| 10. Network theory/Policy network theory/Actor theory/Policy community | Enjorlas and Waldahl (2007) *; Harris and Houlihan (2016); Kerr and Obel (2018) [52]; Lucidarme, Babiak, and Willem * (2018); Hong (2012); Viollet, Scelles, and Ferrand (2020) [53] | 6 | |

| Physical education | 1. Advocacy coalition framework | Houlihan and Green (2006) * [54]; Phillpot (2013) [55] | 2 |

| 2. Bernstein’s conceptual tool | Kårhus (2016) | 1 | |

| 3. Foucault’s idea | Garratt and Kumar (2019) [56] | 1 | |

| 4. Multiple streams | Houlihan and Green (2006) * [54]; Reid and Thorburn (2011) [57]; Uhlenbrock and Meier (2020) [58] | 3 | |

| 5. Network theory/Policy network theory/Actor theory/Policy community | Chen and Chen (2017) | 1 | |

| 6. Notion of policy as process | Stylianou, Hogan, and Enright (2019) [59] | 1 | |

| 7. Punctuated equilibrium theory | Lindsey (2020) [60] | 1 | |

| Sport for all | 1. Advocacy coalition framework | Fahlén and Skille (2017) [61]; Skille (2008) * [62] | 2 |

| 2. Elitism | Tan (2020) * | 1 | |

| 3. Governance | Bergsard, Borodulin, Fahlén, Høyer–Kruse, and Iverson (2019) [63]; Fahlén, Eliasson, and Wickman (2015) [64]; Skille (2008) * [62] | 3 | |

| 4. Multiple constituency evaluation model | Suomi (2004) | 1 | |

| 5. Network theory/Policy network theory/Actor theory | Dobbels, Voets, Marlier, De Waegeneer, and Willem (2018) [65] | 1 | |

| Multi–type | 1. Advocacy coalition framework | Green (2007) [66] | 1 |

| 2. Governance | Green (2009) [67] | 1 | |

| Non–specified | 1. Advocacy coalition framework | Houlihan (2005) * [11] | 1 |

| 2. Governance | Byron and Chepyator–Thomson (2015); Grix (2010) [68]; Grix and Phillpots (2011) [69]; Fahlén and Steling (2016) [70]; Meier and Fuchs (2014) [43]; Phillpots, Grix, and Quarmby (2010) [71] | 6 | |

| 3. Institutional theory/Neo–institutionalism | Sam (2005) | 1 | |

| 4. Multiple streams | Houlihan (2005) * [11] | 1 | |

| 5. Policy network theory | Thomas and Guett (2014) [72] | 1 | |

| 6. Strategic relation approach | Girginov (2001) | 1 | |

| Total | 55 |

| Policy Type | Theory | Included Papers | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elite sport | 1. Compliance theory | Tan, Bairner, and Chen (2018) | 1 |

| 2. Green and Houlihan’s four key policy elements | Park, Tan, and Park (2016) | 1 | |

| 3. Organization resources and first-order capabilities (ORFOC) | Truyens, De Bosscher, and Sortiriadou (2016) [85] | 1 | |

| 4. Sports policy factors leading to international sporting success model (SPLISS) | De Bosscher (2018) [86]; De Bosscher, Knop, Van Bottenburg, and Shibli (2006); De Bosscher, Shibli, and Ch. Weber (2019) [87]; De Bosscher, Shibli, Van Bottenburg, De Knop, and Truyens (2010) [22]; De Bosscher, Shilbury, Theeboom, Van Hoecke, and De Knop (2011) * [88]; Henry, Dowling, Ko, and Brown (2020) [89]; Liston, Gregg, and Lowther (2013) [3]; Padadimitriou and Alexandris (2018) [90]; Patatas, De Bosscher, and Legg (2018) [91]; Sotiriadou, Gowthorp, and De Bosscher (2014) [14]; Truyens, De Bosscher, Heyndel, and Westerbeek (2014) [92]; Valenti, Scelles, and Morrow (2020) [15] | 12 | |

| 5. Stakeholder theory | Chen and Lin (2020) | 1 | |

| 6. System–resource model | De Bosscher, Shilbury, Theeboom, Van Hoecke, and De Knop (2011) * [88] | 1 * | |

| Physical education | 1. Policy network theory | Penney, Petrie, and Fellows (2015) | 1 |

| 2. Whitehead’s conceptualization of physical literacy | Scott, Hill, Barwood, and Penney (2020) [93] | 1 | |

| Sport for all | 1. Bronfenbrenner’s socio-ecological model | Hoekman, Breedveld, and Kraaykamp (2017) [94] | 1 |

| 2. Community theory | Skille (2015) [95] | 1 | |

| 3. Hogwood, Peters, and Jung’s policy change indicators | Tan (2020) * | 1 * | |

| Non–specified | 1. Convergence | Houlihan (2012) | 1 |

| Total | 23 |

| Policy Type | Theory | Included Papers | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elite sport | 1. Games of truth | Piggin, Jackson and Lewis (2009) | 1 |

| 2. Management as discourse | Hu and Henry (2017) | 1 | |

| 3. Morphogenetic approach | Lusted (2018) | 1 | |

| Physical education | 1. Meme | Griggs (2018) | 1 |

| 2. Plowright’s four hierarchy of artefact | Penney (2020) | 1 | |

| 3. Swedish curriculum theory | Janemalm, Quennerstedt, and Barker (2019) [96] | 1 | |

| Sport for all | 1. Markula and Silk’s conceptual model | Dowling (2020) [97] | 1 |

| Total | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ouyang, Y.; Lee, P.-C.; Ko, L.-M. A Systematic Review of the Development of Sport Policy Research (2000–2020). Sustainability 2023, 15, 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010389

Ouyang Y, Lee P-C, Ko L-M. A Systematic Review of the Development of Sport Policy Research (2000–2020). Sustainability. 2023; 15(1):389. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010389

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuyang, Yi, Ping-Chao Lee, and Ling-Mei Ko. 2023. "A Systematic Review of the Development of Sport Policy Research (2000–2020)" Sustainability 15, no. 1: 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010389

APA StyleOuyang, Y., Lee, P.-C., & Ko, L.-M. (2023). A Systematic Review of the Development of Sport Policy Research (2000–2020). Sustainability, 15(1), 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010389