Abstract

Current knowledge of risk management (RM) is mainly limited to single organizations. This paper investigates RM practices from a stakeholders’ perspective applicable to university–industry R&D collaboration (UIC) programs, a particular form of inter-organizational relationship. With a view to reducing the negative impact of risk associated with such UICs, and, as a result, increasing the success rate of the related programs and projects, an RM methodology has been developed from the perspective of the main stakeholders. The results reported here are based on a large-scale UIC between the Bosch Car Multimedia in Portugal and the University of Minho. Three research methods were applied in a complementary way: participant observation over seven years, analysis of various documents supporting the management of the programs and projects, and focus group involving seven key participants from different roles. The proposed RM methodology takes into account the three main stakeholders and their respective RM roles—Program Manager, Program and Project Management Officer, and Project Manager—and helps to manage the risks incurred by a UIC program while, at the same time, emphasizing the importance of taking the stakeholders’ perspective. In inter-organizational contexts, particularly in the case of university and industry, where there is a cultural gap between members, misunderstandings may occur about the role each key stakeholder should play. This paper provides a comprehensive guideline for the application of the methodology by means of a proposed set of specific RM practices. However, the research was conducted using a single case study, therefore limiting the results’ potential for generalization.

1. Introduction

Modern businesses require corporate leaders to be capable of managing with tighter deadlines, smaller budgets, limited resources, and rapid technological change [1]. Given the challenges of globalization and its innovative nature, programs and projects are currently under considerable pressure [2]. In this context, environmental changes can introduce new risks at any level, and organizations must forearm themselves with knowledge comprehensive enough to be able to deal promptly with the risks introduced by this unstable environment [3]. Thus, the academic discipline of risk management (RM) emerges, minimizing the probability and eventual impact of such threats and seizing any opportunities that might arise during the lifecycle of the program or project [4]. Organizations should choose to assume the risk of the projects within a program in a controlled and intentional way to create value, balancing the risk associated with the existence of projects with the eventual rewards that will arise from those projects. The objective is to respond to the stakeholders’ expectations, even if it is necessary to take certain risks to be able to achieve success [1].

In an environment of globalization, fierce competition, and rising research and development (R&D) costs, a collaboration between organizations has become an essential means by which to sustain technological growth and improve innovation [4]. Within this dynamic, universities and industry emerge as partners, and, as such, increase the number of university–industry R&D collaborations (UICs), a particular form of inter-organizational relationship that involves multiple stakeholders who bring together very different cultures and risks [5].

A UIC program is defined here as a temporary organization in a collaborative work environment dealing with a set of projects that are related to specific objective(s), which have heterogeneous partners with collective responsibilities, and, in most cases, have public funding support. UICs are commonly associated with high levels of uncertainty and risk, significant pressure in terms of creativity and innovativeness, the involvement of individually oriented collaborators, and scenarios where project members are often resident in different locations [6,7].

Collaborations between different organizations, even of similar types, are difficult to manage; additionally, the cultural gap between universities and industries increases yet more complexity to their collaboration management [8]. According to the literature, an example of such complexity might involve conflicts over intellectual property, and freedom of expression in publications, as well as differences in priorities, time horizons, and areas of interest/research focus [4]. Thus, research has been forced to identify critical success factors of these types of projects and programs [9]. UICs have revealed several critical success factors that are essentially generic, such as RM [9]. According to Pinto and Pinto [10], the identification and analysis of, and search for solutions to the risks involved in a project, should be carried out on a continuous basis to support the key decision-making of the project.

Stakeholders take on an important role in the analysis of the expectations of each project and in the program and its impact on the organization [11]. They can develop appropriate management strategies to achieve success. For example, stakeholder satisfaction should certainly be identified and managed as an objective of the project and program [12]. The key to effective stakeholder engagement is a focus on continuous communication between all participants, including team members, to be able to understand their needs and expectations, address any issues, and manage interests and conflicts [1].

This paper contributes to a gap within the existing research literature on the phenomenon of inter-organizational RM involving UICs. One of the greatest challenges of UIC programs and projects is to understand the main risks that can exist in these types of collaborations [13]. In the context of RM, stakeholders can follow specific guidelines for reducing the risk associated with UICs, consequently increasing their success rates. Therefore, the main objective of this research is to identify the key RM practices that may be adopted in major UIC programs where several projects are involved, by adopting a stakeholder’s perspective; and led to the adoption of the following research question: How can key RM practices be deployed to effectively manage large UIC programs?

To address this research question, the researchers explored a large-scale UIC case study of Bosch Car Multimedia in Portugal and the University of Minho. This case study enabled the discovery of crucial insights into micro-level RM practices and gives guidance on how key stakeholders can manage the risks involved in a single significant inter-organizational endeavor.

The following section presents the relevant literature for this research. Thereupon the applied research methodology is presented, followed by the research findings on the key RM practices performed by different key stakeholders in a UIC context. The discussion section follows, and, finally, the last section presents the research conclusions, including relevant limitations and recommendations for further work.

2. Literature Review

2.1. University–Industry R&D Collaborations

University–industry R&D collaborations (UICs) is one of the eight different paths in which universities and industries cooperate. Others include (1) mobility of academics; (2) mobility of students; (3) commercialization of R&D results; (4) curriculum development and delivery; (5) lifelong learning; (6) entrepreneurship; and (7) governance.

The current business climate has evidenced an increasing prevalence of UICs, whose collaborations have gained increasing recognition by contributing to the future success of organizations and national economies through the development of technology and improving the efficiency of innovation [4,14].

UICs are based on trusting and committed interactive relationships between partners with the aim of creating mutual value over time by enabling the dissemination of creativity, ideas, and skills, thus promoting a bilateral exchange of knowledge [15]. The main objective of this type of collaboration is the centralization of human resources, especially those in industries where the potential for improvement and innovation is great, and which can lead to the diagnosis of the problem situation and the proposal of new and efficient solutions supported by technical–scientific approaches [7]. The production of new results under one or more predefined research objectives, within various constraints (time, cost, and resources), generally results in a set of benefits for interested parties [2]. Therefore, these partnerships are crucial for industries to be able to increase their investment in R&D through public funding in order to perform better innovation initiatives at lower costs and with shared risks, thus increasing resource capacities and skills and overcoming competition in the global market [6].

The ambition of governments and universities to develop new projects, beyond the two traditional strands of research and education, has increased the relevance of this type of collaboration, namely for the ‘commercialization’ of academic knowledge [16]. Collaborations with industry have become an integral part of university funding; R&D in the higher education sector currently represents a “significant source” of funding by international organizations and companies in many countries [17]. It is therefore crucial to ensure the successful management of UICs so that both partners and society benefit from the inherent advantages of such partnerships [8]. The increasingly active management of such interactions between universities and industry has led to more formal contractual arrangements based on codified norms and standards [15].

There are several reasons why companies might want to collaborate in research with universities. Perkmann et al. [18] identified four main reasons: (1) most public R&D funding programs require the involvement of universities; (2) companies need to have access to research and critical skills to be able to reach the frontier of technology and take it forward; (3) companies seek to prove their problem-solving skills, with academic researchers being hired to solve problems; and (4) these UICs result in a number of secondary benefits, such as the hiring of more talented employees and increasing the reputation and visibility of the companies involved.

From the perspective of the other side of the partnership, Lee [19] identified several reasons why universities collaborate with industry: (1) to supplement funding for their own academic research; (2) to test the practical application of their own research and theorizing; (3) to enhance knowledge in their specific field of research; (4) to promote the mission and scope of the university; (5) to search for business opportunities; (6) to gain knowledge of practical problems that might be of use to higher education; (7) to open the way for curricular and professional internships and opportunities for further professional placement; and (8) to create advantages in ensuring funding for assistants to do research and acquire laboratory equipment.

Despite the multiple opportunities and benefits inherent in such collaborations [2], there are barriers and challenges to such interaction which must be overcome, even in universities and industries with proven experience in such partnerships [20]. Collaborations between different organizations are complex to manage, namely due to the cultural differences which exist between them [21]. Table 1 presents a comparative overview of organizational cultures in universities and industries.

Table 1.

Comparison of organizational culture between universities and industries, adapted from Ivascu et al. [22].

With the increasing occurrence of R&D projects and programs in the context of university–industry collaborations, there follow associated reports of failure. Hence, considerable research has been carried out to identify critical management success factors [9]. Some of these key success factors have been identified which facilitate collaborative R&D programs and projects, where risk analysis, management, and control are emphasized [10]. Furthermore, recent studies have identified that involving and engaging stakeholders, and managing their expectations, have become key factors in reducing the risk of ineffective collaborations [15,23,24]. Therefore, most problems associated with these UIC programs and projects can be mitigated through appropriate RM from a stakeholder perspective.

2.2. Risk Management

The Project Management Institute (PMI) [1] defines risk as “an uncertain event or condition that, if it occurs, has a positive or a negative effect on one or more project objectives”. All projects are risky, since they are unique undertakings with several degrees of complexity, aiming at providing benefits [1]. They are executed under restrictions and assumptions, while simultaneously seeking to meet diverse potentially conflicting and changeable stakeholder expectations [11,12]. Therefore, organizations should be able to deliver value by choosing to take on project risk, considering the balance between risk and reward, in a manageable and deliberative way [1].

The definition of risk involves both uncertain events that may negatively (threats) and positively (opportunities) affect the project. Therefore, RM comprises a set of processes, techniques, and tools that aim to identify, analyze, and respond to the risks of a project, thus focusing on developing strategies that mitigate negative impacts and increase positive impacts on the program and project objectives [1,25]. It addresses risks according to the project’s exposure, adding activities and resources to the budget and adapting the project schedule [1].

Over recent decades, RM has developed quickly enough to become an established knowledge area within the project management discipline [3]. RM is a continuous process, directly dependent on changes in the interior and exterior environment, demanding continuous attention for the identification and monitoring of project risks [26]. When unmanaged, risks can potentially cause the project and program to deviate from the overarching vision and fail to attain its objectives. Consequently, the efficiency of RM is clearly related to the success of the project and program [27].

The relevance of RM has led to its being incorporated in project management standards and frameworks such as PMBOK, PRINCE2, a principles-based sustainable project management methodology (PRiSM), and ISO 21500 [28]. From a general perspective, project RM practices are essential, as they can offer a systematic process for identifying and managing risk to achieve project aims by improving project monitoring and communication between project participants, facilitating the decision-making process and prioritizing required actions, resulting, ultimately, in increasing the project’s chances of success [26,29]. To this end, each project management framework or standard defines a series of steps or processes required for adequate project RM. Indeed, the PMI [25] defines seven chronological processes for RM: plan RM, identify risks, perform a qualitative risk analysis, perform a quantitative risk analysis, plan risk responses, implement risk responses, and monitor risks. By the same token, but with a specific focus on software development projects, RM processes for identifying risk, analyzing risk, risk planning, eliminating risk, and revising and reviewing risk were identified [28].

As for the most appropriate RM approach to be adopted, the literature emphasizes that RM processes and practices must be adapted to the needs and management capabilities of each organization. Thus, project RM support structures have been developed for different types of projects in different contexts. For instance, Lima et al. [30] offer practical advice on project RM in small and medium enterprises. Afshari and Gandomani [28] and Rodríguez and Ortiz [31], respectively, propose RM approaches for software development projects and international development projects.

The above examples illustrate that a support structure that recognizes the specific project and organizational context needs to be defined in order to address the question of the most appropriate RM methodology. A clear RM support structure allows the main stakeholders to be able to understand their role within the adopted RM methodology, with communication as the basis for any successful RM methodology [30]. In addition to this, although the specific factors for the success of RM processes are manifold, some are directly concerned with project stakeholders [25,32]:

- recognition of the value of RM by all project stakeholders;

- individual responsibility and commitment of stakeholders to undertake risk-related activities;

- open and honest communication, with all stakeholders involved in the RM process;

- organizational commitment through alignment of the organization’s objectives and values;

- RM planning appropriate to the project and its potential value to stakeholders.

Stakeholder management plays an important role in achieving the success of UIC programs and projects [11]. In UIC programs, the presence of a high level of uncertainty due to the significant focus on fuzzy aspects of creativity and innovativeness inherent to these programs carries similarly high levels of risk which can cause failures [29]. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify several potential negative risks, such as inadequate stakeholder involvement; disruptions to information flow and communication between stakeholders; strategic misalignment; lack of project sponsorship; and conflict in the attribution of the authorship of intellectual property, as well as positive risks, such as the creation of new unexpected technologies (serendipity), and increase the prestige of the partners [14,33]. Similarly, and unless properly addressed, challenges arising from inter-organizational projects may cause difficulties in project execution. For instance, “one party feeling that they have a key role in the project can create tension between the parties involved, leading to unfavorable inter-organizational relationships” [34]. Therefore, a clear definition of stakeholder participation in the RM processes would help minimize any possible unfavorable inter-organizational relationships.

2.3. Stakeholder Management

The stakeholder concept has attracted enormous interest from organizations over the past 40 years. In the 1980s, [35] a stakeholder was defined as any group or individual that can affect or be affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives, whereas in the 21st century, Savage et al. [36] defined stakeholders as groups or individuals who have an interest in the actions of an organization and have the ability to influence it [37]. Indeed, there are numerous definitions of this concept, but, within the context of project management, the PMI [1] suggests that a stakeholder is an individual, group, or organization that is actively involved in a project or whose interests may affect or be affected positively or negatively by the result of the project’s execution or successful completion.

Every program or project has stakeholders who are impacted by or may generate either beneficial or detrimental impacts on the program or project in question. Some stakeholders have a limited ability to affect the project work or its revenue; others can have a significant impact on the project and its expected returns. Stakeholder satisfaction should be identified and managed as a project aim [12]. The key to effective stakeholder involvement is focusing on ongoing communication with all stakeholders, understanding their needs and expectations, addressing issues as they occur, managing conflicting interests, and promoting appropriate stakeholder involvement in project decision-making and activities [1].

In UIC programs and projects, the interests of stakeholders are affected and influenced in various ways [11]. It is certainly necessary to understand the stakeholders themselves and analyze their interests in order to help in the management of UIC programs and projects [38]. The successful management of stakeholders and their relationships within each organization can lead to a significant improvement in performance and a competitive advantage for the organization [39].

A straightforward project usually involves a large number of stakeholders. UIC programs, however, and by definition, require the involvement of an even larger number of stakeholders. Therefore, in large-scale programs, it is essential to have guidelines for the optimum performance of stakeholders’ roles [1], as there is always a need for balance between having the full picture of stakeholders and becoming overwhelmed by an excess of data [40]. When specifically considering RM, certain guidelines on RM practice for each key stakeholder are essential to achieving the success of projects and programs [41].

Consequently, the RM methodology developed and presented in this paper assumes the stakeholders’ perspective and identifies the main RM practices for the three main stakeholders involved in the RM process: the Program Manager, the Project Manager, and the Program and Project Management Officer. These three key roles are common in single organizations, but the role of the Program and Project Management Officer assumes an even more significant role in inter-organizational programs and projects [42].

3. Research Methodology

This research has sought to deepen the understanding of how RM practices can be deployed to successfully achieve UIC programs. Thus, a UIC program is here understood to be an inter-organizational system, and, consequently, RM is framed in this inter-organizational system. Organizational studies have mainly been framed in line with a classic functionalistic approach [43], indeed there are numerous quantitative risk analysis approaches to projects [44]. However, several limitations and inadequacies have been identified in both organizational studies and project studies [8,45].

How organizations effectively manage the risk of inter-organizational programs is not an objective reality, and, epistemologically, the interaction with the participants to investigate the problem is particularly important. Ontologically, the reality behind the research problem is seen as subjective, which led researchers to a social constructionism approach and its related theoretical orientation known as constructivism is that realities are constructed rather than discovered [46].

Constructionism had important implications for how we designed the research study on inter-organizational RM practices in the context of UIC programs. Firstly, we need approaches that elucidate the socially and culturally incorporated nature of RM in an inter-organizational context, and that facilitate a greater understanding of the relationship between individuals and social context. Secondly, given the notion of constructed/contested versions of reality discussed, the case study needed research methods that bring contradictions and struggles over meaning and surface. Therefore, it utilized the combination of three research methods: participant observation, document analysis, and focus group.

3.1. Case Study Background

This piece of exploratory empirical research uses, as a case study, the strategic partnership established between Bosch Car Multimedia in Portugal (Bosch) and the University of Minho (UMinho), which was established in 2012 to develop and produce advanced multimedia solutions for cars. Approximately ten years into the partnership, the strategic collaboration established between Bosch and UMinho encompasses three investment phases (R&D programs). With the sponsorship of the Portuguese Government and through competitive public funds, the average funding rate is 50% Bosch and 75% UMinho. At the technological level, the problems and challenges which arise ensure the development of technologies and methodologies whose technological maturity rates are between four and seven on the Technological Readiness Levels scale.

UMinho is a young higher education institution, ranked in 2019, by the Times Higher Education, in the top 150 universities of the world. It has high levels of collaboration with industry; about 250 R&D agreements with industrial partners are contracted annually.

Bosch in Portugal has, over the years, become one of the biggest automotive suppliers in the country. Bosch in Portugal allocates around 12% of its turnover to R&D.

The case study involved the analysis of three consecutive phases of investment, as summarized in Table 2. The first phase was named the HMIEXCEL program, the second phase Innovative Car HMI program, and the third phase Crossmapping the Future.

Table 2.

Three investment phases (programs) in the Bosch and UMinho partnership.

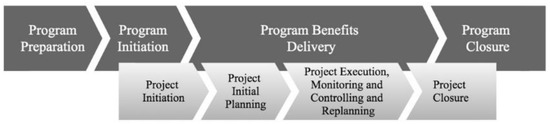

The Bosch–UMinho partnership recognizes the value of project management in supporting the successful running of the collaboration [47]. To this end, the two parties established a Governance Model based on a specifically developed management approach called the Program and Project Management (PgPM) approach [48], which was especially dedicated to Program and Project Management by R&D contracts in university–industry collaboration. Figure 1 illustrates the approach’s program management and project management lifecycles.

Figure 1.

PgPM approach, adapted from Fernandes, Pinto, Machado, Araújo, and Pontes [48].

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

This research aimed to use existing knowledge as its basis and then learn from the experience of the program and project stakeholders [49]. The research methods applied during the case study were participant observation, document analysis, and focus group [50]. Using participant observation and document analysis, the context was studied in detail by means of various documents supporting the management of the programs and their projects. The most relevant documents analyzed included the governance model, which established the program and project risk management processes, as well as several documents that supported the RM of the program and its constituent projects (e.g., project charters, technical and financial program progress reports, program risk register, project risk registers, and the program and project lessons learned register). The analysis of several documents was crucial to better understanding the case study context and the current RM practices.

Observation also played a crucial role in the context of this research by driving the insider researcher or fieldworker to have closer contact with the object of study in its natural environment, helping the researcher to grasp the organizational context [51]. Observation provided the insider researcher with experiential and observational access to the actualities of the world of meaning [52]. Observations were made, over seven years, of daily work routines, workshops, meetings at every organizational level, and celebrations, as well as informal gatherings during the daily RM activities of the program members. Particularly, the progress meetings allowed participants to identify and document the expected project risks and how RM was conducted. Several written sets of field notes were prepared during the participatory observations, where each set of notes comprised numerous informal interactions with the staff, as well as related reflections thereupon. Among other things, these observations included more than 600 meetings. Listening to and questioning collaborative program participants and their conversations provided information about everyday organizational life and the emerging RM practices of this major collaboration. Therefore, through participant observation, it was possible to realize and perceive the UIC context and identify the potentially essential RM practices.

Observation is often criticized for its potential lack of reliability [49]; however, coupled with other qualitative methods, it is an important holistic research method, which enables researchers to gain a better understanding of the insider’s perspective [53].

A focus group was composed of seven members from different roles (Program Manager, Project Manager, and Program and Project Management Officer), in order to provide a systematic collection of different people’s experiences, interpretations, and feelings within their naturalistic settings. The main objective of this focus group was to discuss the main RM practices of these key stakeholders and to consider a specific RM methodology developed for R&D programs and projects in the UIC context. Therefore, they collectively provided their opinion on the RM activities during the program management lifecycle.

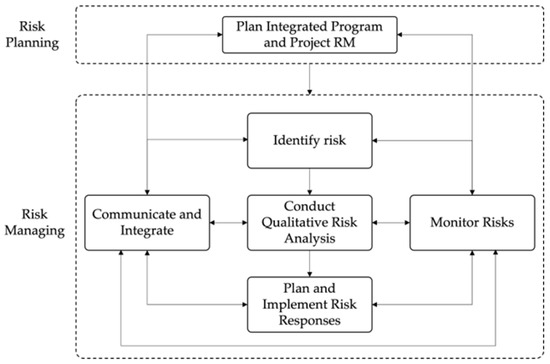

The preparation of the focus group sessions involved deciding on some questions in advance, such as ‘what are the main challenges of managing risks in UIC programs?’, to begin and guide the discussion, as well as to prepare the researcher to be ready to provide feedback on what was said [54]. During the sessions, the focus group moderator (insider researcher) used auxiliary materials, such as the RM framework conceptualization (Figure 2), as well as explanatory notes on the Program and Project Management approach [48].

Figure 2.

Integrated program and project RM methodology.

The conduction of this research placed a very high emphasis on ethics. Therefore, the confidentiality and anonymity of all participants in the research were assured. All participants in the focus group had their consent sought prior to the commencement of their participation. All participants in the focus group were also informed that they could withdraw from the focus group at any point in time, without giving a reason and without implications for them. In addition, participants were informed, in advance and by email, about the purpose of the study and had the opportunity to ask questions about it.

The focus group lasted two hours. The transcript of the focus group was not coded. However, it was scanned by three of the authors and its relevant contents were selected to support the claims made from the observations and document analysis.

The central premise of this study was to move away from a high-level approach to RM to identify a systematic set of key RM practices to be performed by the Program Manager, PgPMO Officer, and Project Manager. However, one major issue of in-depth longitudinal case studies is the large amount of data collected, which must not result in the adoption of reductionist approaches, or the inference of conclusions based on slender evidence [49]. Therefore, an interpretive sense-making strategy was adopted to produce meaning from the case study data [55]. In such a strategy, the data are understood as embedded in the context of the case and the fieldworker’s claims about the phenomenon can be strengthened by the support of such data [56]. To analyze the data, a fourth-step approach was designed and thoroughly followed.

First, the field notes of the insider researcher, resulting from participant observation and document analysis, were scanned by two other authors, and the results were discussed among them to develop the RM methodology comprised by six RM processes. Second, the documents selected were scanned and coded based on the main six RM processes. Third, as a form of ‘member-checking’ [56], three of the authors discussed preliminary findings in a focus group to validate them with seven key members of the Bosch and UMinho collaboration. The ultimate step was finalizing the contributions, which involved a final interpretive process through multiple readings and iterations between tentative assertions and raw data, drafting successive versions of the RM methodology, until the present form was determined.

Finally, it is worthy of mention that the RM methodology adopting a stakeholders’ perspective was developed collaboratively among the seven experts involved in the focus group; in this respect, it can be said that this research influenced the RM approach adopted in the UMinho and Bosch R&D collaborations thereafter.

4. Results

4.1. Risk Management in a UIC Context

Using participant observation and document analysis it was possible to understand how RM was performed in the UMinho and Bosch collaboration and with which actors.

Bosch and UMinho invested in a dedicated Program and Project Management Office (PgPMO) infrastructure, which included both Bosch and UMinho members. The PgPMO plays a supportive role [42], whose principal objective is to support both Program Managers and Project Managers and their teams, throughout the lifecycle of the program and its projects, especially in their RM practices.

During the ‘Program Initiation’ phase, key project stakeholders are involved in Alignment Workshops organized by the Program Manager and supported by the PgPMO team, which aim to align the project’s objectives with stakeholders’ expectations. During these Alignment Workshops, the projects’ potential risks are also identified. Then the Program Charter and the Project Charters are created for each project, streamlining the overall program’s aims with those of the projects. These Project Charters include all the initial risks which have been identified during the ‘Program Preparation’ phase and included in the Funding Application, as well as any risks later identified during the Alignment Workshops.

During the ‘Program Benefits Delivery’ phase, progress meetings are held monthly by the PgPMO team members and project teams, which result in Project Progress Reports that include the most up-to-date information on the project risks. These risks are then integrated into the Project Risk Register and the Program Risk Register.

During the ‘Program Closure’ phase, every effort is made by the PgPMO team to identify, document, analyze, store, and retrieve the lessons learned from each project and from the overall program, giving rise namely to a Risk Breakdown Structure, which can be updated to support the risk identification of future UIC programs and projects, as well as a risk database of potential risks in the context of UIC programs.

4.2. An Integrated Program and Project RM Methodology

The consolidated analysis of the study analysis resulted in a new integrated program and project RM methodology, specifically developed for UIC contexts, as presented in Figure 2.

This RM methodology focuses primarily on the role that should be adopted by stakeholders during the R&D program and project lifecycles and comprises six RM processes. The first of these processes encompasses planning how to manage risk in the context of a particular UIC context. This plan includes a definition for the set of five other key integrated RM processes to be adopted. This set of five RM processes should be conducted throughout the program and project lifecycles at periods that do not compromise resource and time limitations, taking into account the existing levels of RM knowledge of the various stakeholders in the temporary organization.

The Project Management Institute’s Practical RM Standard [25] was used as a theoretical base for the development of this RM methodology, although it is worth noting that the processes proposed by this standard are common to most Project Management standards, including ICB 4 [57] and ISO 31000 [58].

Considering the RM practices observed and potential information available in the Bosch and UMinho case study, the quantitative risk analysis process suggested by many of these standards [1,25,57,58] is not proposed here.

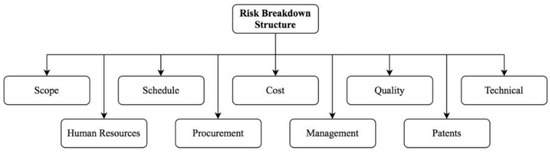

The first key RM process that results from the UIC context analysis is the ‘Plan Integrated Program and Project RM’. This plan defines the several RM practices to be applied by different program stakeholders throughout the program and project lifecycles, aiming at enhancing and optimizing the projects and overall program results. In the Bosch and UMinho case study, the Integrated RM Plan establishes the existence of a Risk Register—the central tool in the RM methodology, which allows for the registration and easy consultation of all the identified and collected information on risk, both at the project and program levels, by means of its identification, qualitative analysis, response plans, and monitoring and control. In parallel, the Integrated RM Plan also defines the Risk Breakdown Structure to be used in the Risk Register. Figure 3 shows the Risk Breakdown Structure adopted at Bosch and UMinho, which can, of course, be used in other similar collaborations.

Figure 3.

Risk breakdown structure adopted at Bosch and UMinho UIC programs.

The ‘Identify Risks’ step is a critical RM process in the success of a particular project or program. The risk event can be characterized by its causes and its effects on the objectives of the project or program. The possible causes of risks are uncertainties related to the project or program, which might cause a positive or negative effect on its objectives. They can be identified by assessing the sources of risk, which, in addition to environment, may well include restrictions, assumptions, stakeholders, lessons learned, internal processes, standards, and regulations. During the RM process, the ‘Identify Risks’ step is also key to using the various categories of the Risk Breakdown Structure (Figure 3) as input to assist the program management (at the program level) and project management (at the project level).

After identifying the risks, a ‘Conduct Qualitative Risk Analysis’ step must be followed, qualifying the probability of occurrence and the impact of each risk. The level of risk obtained (probability * impact) is a major factor for risk prioritization. Although not entirely linear, the higher the level of risk calculated, the higher the priority of risk response planning should be [1].

Typically, project risk impact is measured in four dimensions: scope, time, cost, and quality [1]. To evaluate this impact, the weight to be assigned to each dimension should be established by the UIC Steering Committee, since it is this body that is responsible for the program’s success and, therefore, for evaluating what is most important in this regard. Probability and impact can be qualified according to the parameters shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameters for qualifying the probability and impact of each risk identified.

The ‘Plan and Implement Risk Responses’ process uses the information gathered when identifying and qualitatively analyzing risks to elicit a risk response action plan and then put it into practice.

Despite no evidence of robust or structured practices oriented towards processing risk response in the Bosch and UMinho case study, some of their good practices should be implemented: collecting assumptions associated with the occurrence of the risk, performing analysis of the causes and effects of the risks in question, developing and executing a sound communication plan during the response phase, identifying those responsible for handling and monitoring the risk, defining the type(s) of actions to be taken, and finally, understanding if there will be other risks associated with the implementation of a risk response action [1].

Risk response strategies for addressing threats and opportunities can be generalized, as shown in Table 4. When planning for risk responses, the circumstances defining the type of risk response action, the starting period, and the person responsible for the plan should be identified. Thus, for the choice of actions to be effectively adopted, the respective responsible party must adopt a response logic guided by the cost–benefit ratio between the levels of inherent and residual risk. The purpose of the risk responses is to change the initial risk level (inherent risk) to a new risk level (residual risk) that favors the achievement of the program and/or project success. In the Bosch and UMinho case study, a database of risk response strategies for the most common management risks was created to guide future programs [14].

Table 4.

Risk response strategies.

Once the strategies for responding to the identified risks have been defined, it is necessary to continuously ‘Monitor Risks’ and control them, identifying changes in the level of the risks identified and adjusting the response plans accordingly, as well as identifying new risks (returning to the beginning of the RM process). During the risk monitoring process, stakeholders assume a fundamental role in decision making and risk assessment.

Throughout the RM process, a special focus is placed on the team, which is responsible for identifying new risks, assessing the level of risk, and developing new strategies to respond to those risks. To achieve the success of programs and projects, throughout the execution of RM, good communication of the state of the risks and the integration of this process into all the other management and technical execution processes must be ensured. To this end, all stakeholders involved in the project and program must be identified to then be able to ensure that information regarding the RM of a given object is shared and ensure that those likely to influence or be influenced by this risk know, as soon as possible and to a greater extent, the actions required for RM which achieves an adequate and effective response. Thus the ‘Communicate and Integrate’ process appears as a new management process in the RM methodology here presented.

4.3. Integrating Stakeholders into the RM Methodology

During the Bosch and UMinho case study, a sustained effort was made by the PgPMO team to draw the attention of the project management teams to identify new risks, reassess the level of risk, and develop risk response strategies. However, little attention was paid to these activities by those responsible and other project members, thus indicating limited recognition of the value of RM practices in the context of this UIC.

However, RM practices must be systematically implemented given that they are so critical to the success of UICs [4,8]. Emphasis should be placed on the definition of structured objectives, good monitoring of progress, and effective communication and integration at the program and project levels, wherein program and project stakeholders assume an essential role.

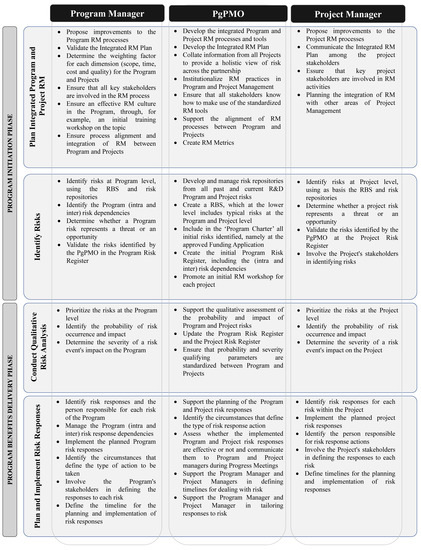

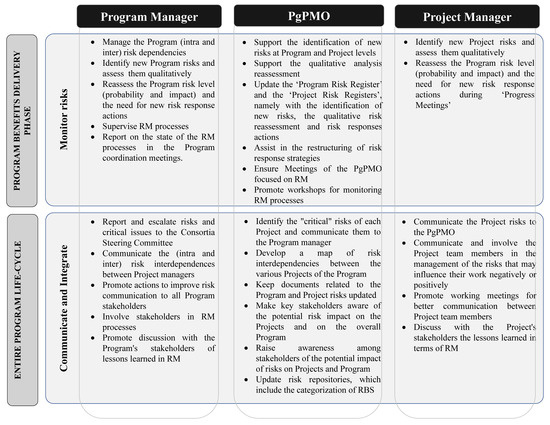

From the case study analysis, thorough guidance is given for each of the six key RM processes presented in Figure 2, from the perspective of the main management stakeholders: Program Manager, Project Manager, and PgPMO. Figure 4 summarizes these specific RM practices throughout the program management lifecycle.

Figure 4.

RM practices: the Program Manager, PgPMO Officer, and Project Manager’s perspectives.

During the focus group, it was possible to perceive some of the aforementioned challenges when discussing the topic of RM. In the Bosch and UMinho case study, the Program Manager and PgPMO members guarantee the entire RM process. As mentioned above, besides promoting this topic at the different structural levels (program and project), they also identify and track risks, discuss risk response plans, and follow up on the whole RM process.

Although Program Managers and PgPMO members have made efforts to train project teams in RM, there was some resistance from these elements. In addition, although Project Managers are actively involved in identifying risks and solving technical risks, their awareness of managing risks was limited. This is common in the UIC context since most Project Managers are not trained Project Management professionals; they are researchers with academic careers.

When holding the usual Progress Meetings between stakeholders, risk identification was not always valued, and sometimes the teams did not address the RM processes in their meetings due to the lack of time. In this sense, some PgPMO members and Project Managers decided to hold specific RM Meetings to build the initial Risk Register and facilitate the entire subsequent process.

In fact, the PgPMO played a very important role in the development of RM processes and integrated tools to support the Program Manager and the Project teams in RM practices and in keeping all the risk information up to date. However, there were projects where these RM meetings did not take place, as there was a certain limitation and resistance on the part of the project teams to analyze risks; so risk analyses were carried out during the regular progress meetings.

The emphasis and focus on appropriate RM practices in the Bosch and UMinho collaboration has contributed to enhancing the probability of success for its projects and programs and to the sustainability of the partnership. The existence of general progress in RM practices since the first program is to be noted. This was recognized by all seven focus group participants. Risks were not previously a common subject for discussion but are now systematically addressed by the most experienced researchers more directly involved in the collaboration.

Following on from this focus group and taking the substantial growth of the partnership, time was afforded to share some suggestions regarding the future of the partnership and the processes of RM in the UIC context.

According to focus group participants, RM training actions or workshops must be held to train project teams and involve them more deeply in the RM processes. This initiative has already been explored by the Program Management team in the Bosch and UMinho partnership, although only one Project RM training session has been carried out so far.

It is also fundamental to reinforce the point that those responsible for Program Management should play an active role in fostering interest among project teams in this type of training so that they can discuss the objectives of the project and/or program and relate them to any risks and problems. This will lead to greater involvement of the project teams and consequently to a more careful survey of risks.

The Project Manager participants reinforced the fact that close involvement of the Program Manager in the RM processes would have beneficial effects right from the start of the program. During the ‘Program Preparation’ phase, when applying for funding, the identification of multiple risks helps to justify the innovative, R&D nature of each project. Thus, the identification of technical and management risks helps prove the level of innovation inherent in each project, since the more innovative a project is, the more associated risks it has. Additionally, the identification of risks increases the likelihood of acceptance of an application for funding for a UIC R&D project.

According to PgPMO participants, the continuous improvement of the partnership would depend on the more rigorous selection of Project Managers. At present, they deem Project Managers to be limited in their RM capabilities; indeed this factor is well notorious during RM practice implementation. Another course of action would be to hold periodic meetings dedicated exclusively to RM, according to the rhythm of the work of each project team.

In summary, the focus group participants recognized that, although they have implemented several important RM practices, these could be better structured and improved upon. When questioned as to what practices they would implement to improve RM, there were numerous suggestions:

- training and awareness raising of RM among project team members;

- identification and appropriate classification of risks;

- regular meetings focused on RM;

- communication of risk to the whole governance structure;

- training of Project Managers for RM;

- creation of a position of Chief Risk Officer (CRO);

- implementation of a set of internal workshops with experienced speakers in UICs and RM;

- prioritization of risks through qualitative analysis, response planning, and risk monitoring;

- carrying out simulations to predict different types of scenarios.

Given the size and maturity of the partnership in question, RM practices in UIC programs and projects need to be improved. Indeed, the development of the methodology and the suggestions made by the stakeholders that participated in this research confirmed the importance of RM to the UIC program and project success.

5. Discussion

The proposed program and project RM methodology is an innovative contribution to the field of UIC, which was grounded in the analysis of a case study based on the long-established relationship between Bosh and UMinho.

The literature highlights the fact that RM processes and practices must be adapted to the needs and management capabilities of each organization [28,30]. In this regard, collaborations between different organizations present certain specific challenges, which are mainly twofold. On the one hand, in this type of collaboration, the identification of risks and their qualification and analysis are the main challenges faced [4]. On the other hand, challenges arise from the cultural gap between university and industry [34] and tension between stakeholders caused by misunderstandings in the role each key stakeholder should play [30]. Concerning the first challenge, different structures and processes for RM have been incorporated into project management standards and frameworks, such as PMBOK, PRINCE2, sustainable project management methodology (PRiSM), and ISO 21500 [28]. In addition, in specific RM proposals for software development projects and international development projects, groups of processes have been established [28,31]. In this regard, the proposed RM methodology incorporates a number of processes well-known in the literature, such as risk identification, qualification, response, and monitoring. It gives a micro-level perspective on RM by identifying the detailed RM practices for each key stakeholder (Program Manager, PgPMO, and Project Manager), and contextualizes the RM process to projects and programs in UIC, considering, for instance, the risk associated with patents as part of the Risk Breakdown Structure.

In addition to this, and considering the relevance of communication and coordination between stakeholders in UIC projects and programs, the proposed RM methodology incorporates ‘Communicate and Integrate’ as an RM process. Thus, in contrast to the RM planning proposed by the PMI [1,25], the ‘Communicate and Integrate’ step appears as a new RM process. Additionally, by recognizing the importance of a clear definition of stakeholder participation in RM processes [34], the proposed methodology offers detailed guidance on the role of each main stakeholder in RM processes throughout the UIC program management lifecycle.

As such, RM challenges highlighted in the literature are addressed and taken into account in the proposed program and project RM methodology. The proposal offers an RM support structure based on widely recognized RM processes but complements them with the incorporation of the ‘Communicate and Integrate’ process into the RM cycle and with the definition of the stakeholders’ roles as part of the RM planning. Consequently, the proposed RM methodology can be considered as an initial support structure for designing RM processes in UIC contexts.

6. Conclusions

This research has investigated the key RM practices in the context of large university–industry R&D collaboration (UIC) programs to increase the probability of success of these types of collaborations.

It used the case study as a research strategy and participant observation, document analysis, and focus groups as research methods [49]. The case study selected was a strategic partnership established between Bosch Car Multimedia in Portugal (Bosch) and the University of Minho (UMinho).

An RM Methodology was developed for UICs, adopting a stakeholder’s perspective. Based on the literature review for RM and throughout the case study analysis, an integrated program and project RM methodology was proposed, which incorporates the perspective of the main stakeholders, detailing the most cited RM practices to be performed by the main stakeholders: Program Manager, PgPMO, and Project Manager, throughout the program lifecycle (See Figure 4).

An important contribution of the RM methodology developed herein is that it details how to manage the risks inherent to a UIC program where several projects are involved while emphasizing the importance of a stakeholder’s perspective on inter-organizational RM.

The results of this research also have practical contributions, bringing a clearer vision of the value of RM through a compilation of RM practices, taking a stakeholder’s perspective that can be used as a blueprint by practitioners who aim to improve RM in inter-organizational collaborating contexts.

As with any methodology, the RM methodology developed herein portrays a partial and incomplete view of reality, which should be used cautiously by academic and industrial partners. They should modify it and adapt it to their own specific circumstances.

Furthermore, as with any research based on a single case study, this project has limitations in the generalization of its results. The results are extrapolated from a particular case and may thus be dependent on its specific context, whereas the reasoning may also be influenced by random factors.

That said, future studies may well benefit from multiple case studies and cross-checking conclusions between them to strengthen the RM methodology, thereby increasing the generalizability of the results. In this regard, the methodology in question is not supposed to be immutable and may certainly be updated when required. What is essential is that it evolves naturally, as the roles of the stakeholders in question evolve, adapting to the requirements of the organizations’ new programs and projects and becoming more effective and efficient over time.

Additionally, it may also be useful to focus the methodology on other stakeholders, such as project team members. The adoption of RM practices by other stakeholders may well lead to greater commitment on the part of stakeholders to the field of RM. Moreover, R&D collaborations among organizations take many forms, such as collaborations between only industry members or between only universities and knowledge institutes. These cases, although similar, still have differences that also deserve research attention. Finally, a more quantitative approach could also be used in future case studies, for example, using key performance indicators to measure the impact of adopting RM practices in inter-organizational R&D contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.F.; methodology, G.F. and A.T.; validation, G.F., A.T. and M.A.; formal analysis, G.F., J.D. and A.T.; investigation, G.F., J.D., A.T. and C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.F., J.D. and C.M.; writing—review and editing, A.T. and M.A.; supervision, G.F. and A.T.; project administration, G.F.; funding acquisition, G.F., A.T. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is sponsored by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, under the project UIDB/00285/2020, UIDB/00319/2020, and LA/P/0112/2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the focus group participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- PMI. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge: PMBOK Guide, 6th ed.; PMI: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2017.

- Fernandes, G.; O’Sullivan, D. Benefits management in university-industry collaboration programs. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhawari, S.; Karadsheh, L.; Talet, A.N.; Mansour, E. Knowledge-Based Risk Management framework for Information Technology project. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 32, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, T.; Pashby, I.; Gibbons, A. Managing collaborative R&D projects development of a practical management tool. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 395–404. [Google Scholar]

- Hanel, P.; St-Pierre, M. Industry–University Collaboration by Canadian Manufacturing Firms*. J. Technol. Transf. 2006, 31, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, T.; Pashby, I.; Gibbons, A. Effective University—Industry Interaction: A Multi-case Evaluation of Collaborative R&D Projects. Eur. Manag. J. 2002, 20, 272–285. [Google Scholar]

- Tunca, F.; Kanat, Ö.N. Harmonization and Simplification Roles of Technology Transfer Offices for Effective University-Industry Collaboration Models. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 158, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.; O’Sullivan, D. Project management practices in major university-industry R&D collaboration programs—A case study. J. Technol. Transf. 2022, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.; Santos, J.; Ribeiro, P.; Ferreira, L. Critical Success Factors of University-Industry R&D Collaborations. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, in press.

- Pinto, J.; Pinto, M. Critical Success Factors in Collaborative R&D Projects. In Managing Collaborative R&D Projects: Leveraging Open Innovation Knowledge-Flows for Co-Creation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, G.; Capitão, M.; Tereso, A.; Oliveira, J.; Pinto, E.B. Stakeholder Management in University-Industry Collaboration Programs: A Case Study. In International Conference Innovation in Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Micán, C.; Fernandes, G.; Araújo, M. Disclosing the Tacit Links between Risk and Success in Organizational Development Project Portfolios. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.; Domingues, J.; Tereso, A.; Pinto, E. Critical Management Risks in Collaborative University-Industry R&D Programs. In World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 106–115. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, G.; Martins, A.R.; Pinto, E.B.; Araújo, M.; Machado, R.J. Risk Response Strategies for Collaborative University-Industry R&D Funded Programs. In International Conference on Innovation, Engineering and Entrepreneurship; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 522–529. [Google Scholar]

- Plewa, C.; Quester, P. Key drivers of university-industry relationships: The role of organisational compatibility and personal experience. J. Serv. Mark. 2007, 21, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhl, M.; Pausits, A. Third mission indicators for new ranking methodologies. Lifelong Educ. XXI Century 2013, 1, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, J.; Okamuro, H. Internal and external discipline: The effect of project leadership and government monitoring on the performance of publicly funded R&D consortia. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 840–853. [Google Scholar]

- Perkmann, M.; Neely, A.; Walsh, K. How should firms evaluate success in university-industry alliances? A performance measurement system. RD Manag. 2011, 41, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S. The Sustainability of University-Industry Research Collaboration: An Empirical Assessment. J. Technol. Transf. 2000, 25, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsanzumuhire, S.U.; Groot, W. Context perspective on University-Industry Collaboration processes: A systematic review of literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneel, J.; D’Este, P.; Salter, A. Investigating the factors that diminish the barriers to university–industry collaboration. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivascu, L.; Cirjaliu, B.; Draghici, A. Business Model for the University-industry Collaboration in Open Innovation. Procedia Econ. Finance 2016, 39, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.; Wakoh, H. Universities and Technology Transfer in Japan: Recent Reforms in Historical Perspective. J. Technol. Transf. 2000, 25, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybnicek, R.; Königsgruber, R. What makes industry–university collaboration succeed? A systematic review of the literature. J. Bus. Econ. 2019, 89, 221–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMI. Practice Standard for Project Risk Management, 1st ed.; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2009.

- Tchankova, L. Risk Identification—Basic Stage in Risk Management. Environ. Manag. Health 2002, 13, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, J.; Kock, A. An empirical investigation on how portfolio risk management influences project portfolio success. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, M.; Gandomani, T.J. A novel risk management model in the Scrum and extreme programming hybrid methodology. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. (IJECE) 2022, 12, 2911–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lin, W.; Huang, Y.-H. A performance-oriented risk management framework for innovative R&D projects. Technovation 2010, 30, 601–611. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, P.F.D.A.; Marcelino-Sadaba, S.; Verbano, C. Successful implementation of project risk management in small and medium enterprises: A cross-case analysis. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2021, 14, 1023–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rivero, R.; Ortiz-Marcos, I. The methodology of the Logical Framework with a Risk Management Approach to Improve the Sustainability in the International Development Projects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Hwang, B.G.; Low, S.P. Critical success factors for enterprise risk management in Chinese construction companies. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2013, 31, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tworek, P. Plan Risk Response as a Stage of Risk Management in Investment Projects in Polish and U.S. Construction—Methods, Research. Ann. Alexandru Ioan Cuza Univ. Econ. 2013, 59, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Krechowicz, M. Towards Sustainable Project Management: Evaluation of Relationship-Specific Risks and Risk Determinants Threatening to Achieve the Intended Benefit of Interorganizational Cooperation in Engineering Projects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; McVea, J. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management. In The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, G.T.; Nix, T.W.; Whitehead, C.J.; Blair, J.D. Strategies for assessing and managing organizational stakeholders. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1991, 5, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. The Relationship Between Environmental Commitment and Managerial Perceptions of Stakeholder Importance. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, A.A.; Cavana, R.Y.; Jackson, L.S. Stakeholder Analysis for R&D Project Management. RD Manag. 2002, 32, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Benn, S.; Abratt, R.; O’Leary, B. Defining and identifying stakeholders: Views from management and stakeholders. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskerod, P.; Lund Jepsen, A. Project Stakeholder Management, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Eskerod, P. Stakeholder Perspective: Origins and Core Concepts; Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, G.; Pinto, E.B.; Araujo, M.; Machado, R.-J. The roles of a Programme and Project Management Office to support collaborative university–industry R&D. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2020, 31, 583–608. [Google Scholar]

- Burrell, G.; Morgan, G. Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis. Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nesticò, A.; De Mare, G.; Maselli, G. An economic model of risk assessment for water projects. Water Supply 2020, 20, 2054–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avenier, M.-J. Shaping a Constructivist View of Organizational Design Science. Organ. Stud. 2010, 31, 1229–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, V. Social Constructionism, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, G.; O’ Sullivan, D.; Pinto, E.B.; Araújo, M.; Machado, R.J. Value of Project Management in University–Industry R&D Collaborations. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2020, 13, 819–843. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, G.; Machado, R.J.; Pinto, E.B.; Araujo, M.; Pontes, A. A Quantitative Study to Assess a Program and Project Management Approach for Collaborative University-Industry R&D Funded Contracts. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation/IEEE lnternational Technology Management Conference (ICE/ITMC), Trondheim, Norway, 13–15 June 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Angrosino, M.V. Recontextualizing Observation: Ethnography, Pedagogy, and the Prospects for a Progressive Political Agenda. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 729–745. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M.; Sköldberg, K. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, L. Observation: A Complex Research Method. Libr. Trends 2006, 55, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, J.; McDonagh, D. Focus Groups: Supporting Effective Product Development; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Van Marrewijk, A.; Ybema, S.; Smits, K.; Clegg, S.; Pitsis, T. Clash of the Titans: Temporal Organizing and Collaborative Dynamics in the Panama Canal Megaproject. Organ. Stud. 2016, 37, 1745–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanow, D. Qualitative-Interpretive Methods in Policy Research. In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- IPMA. ICB4: Individual Competence Baseline for Project, Programme & Portfolio Management, 4th ed.; International Project Management Association: Nijkerk, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- NP ISO 31000:2018; Gestão do Risco. Instituto Português da Qualidade: Setúbal, Portugal, 2018.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).