Driving Sustainable Innovation in New Ventures: A Study Based on the fsQCA Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Retrospection

2.1. Open Innovation Theory

- (1)

- It reflects socioeconomic shifts in work patterns, with skilled workers seeking a portfolio of jobs rather than a lifetime of work;

- (2)

- Globalization expands the scope of the market, thereby allowing a finer division of labor;

- (3)

- An enhanced market system allows businesses to trade ideas;

- (4)

- New technologies provide cooperation and coordination across geographic distances.

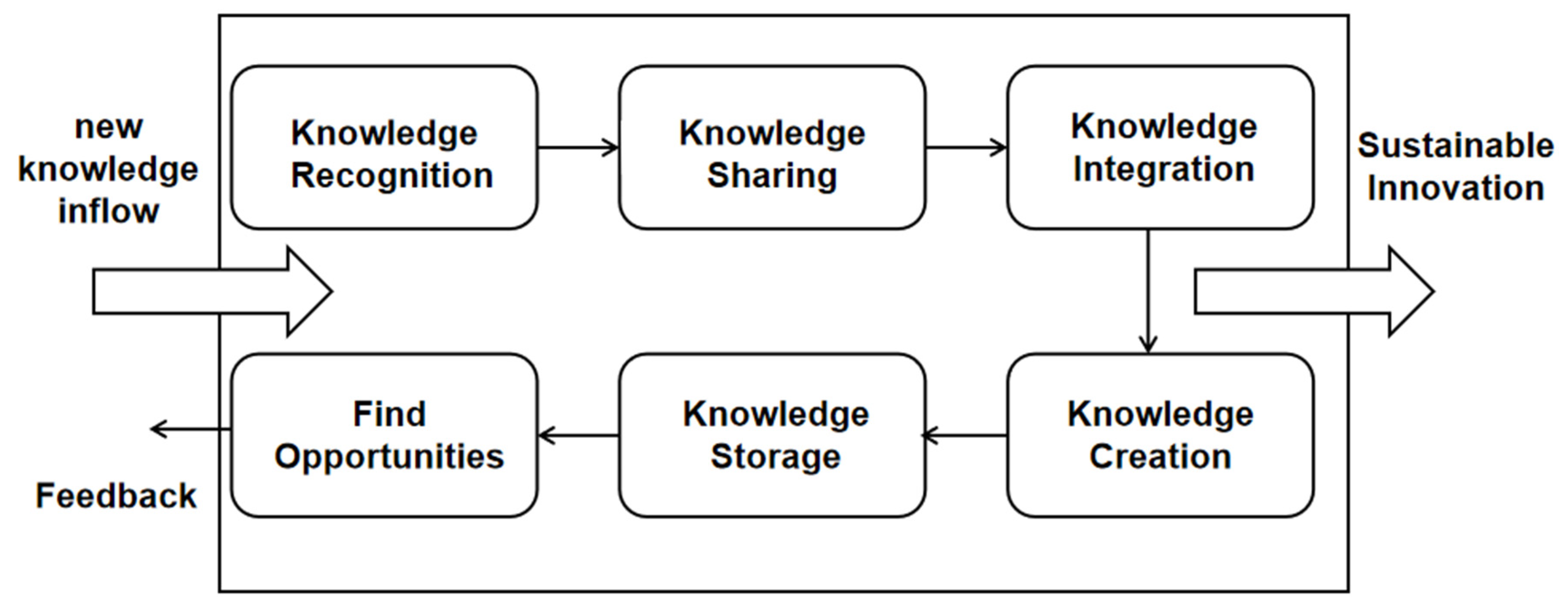

2.2. Knowledge-Based View

2.3. Dynamic Capability Theory

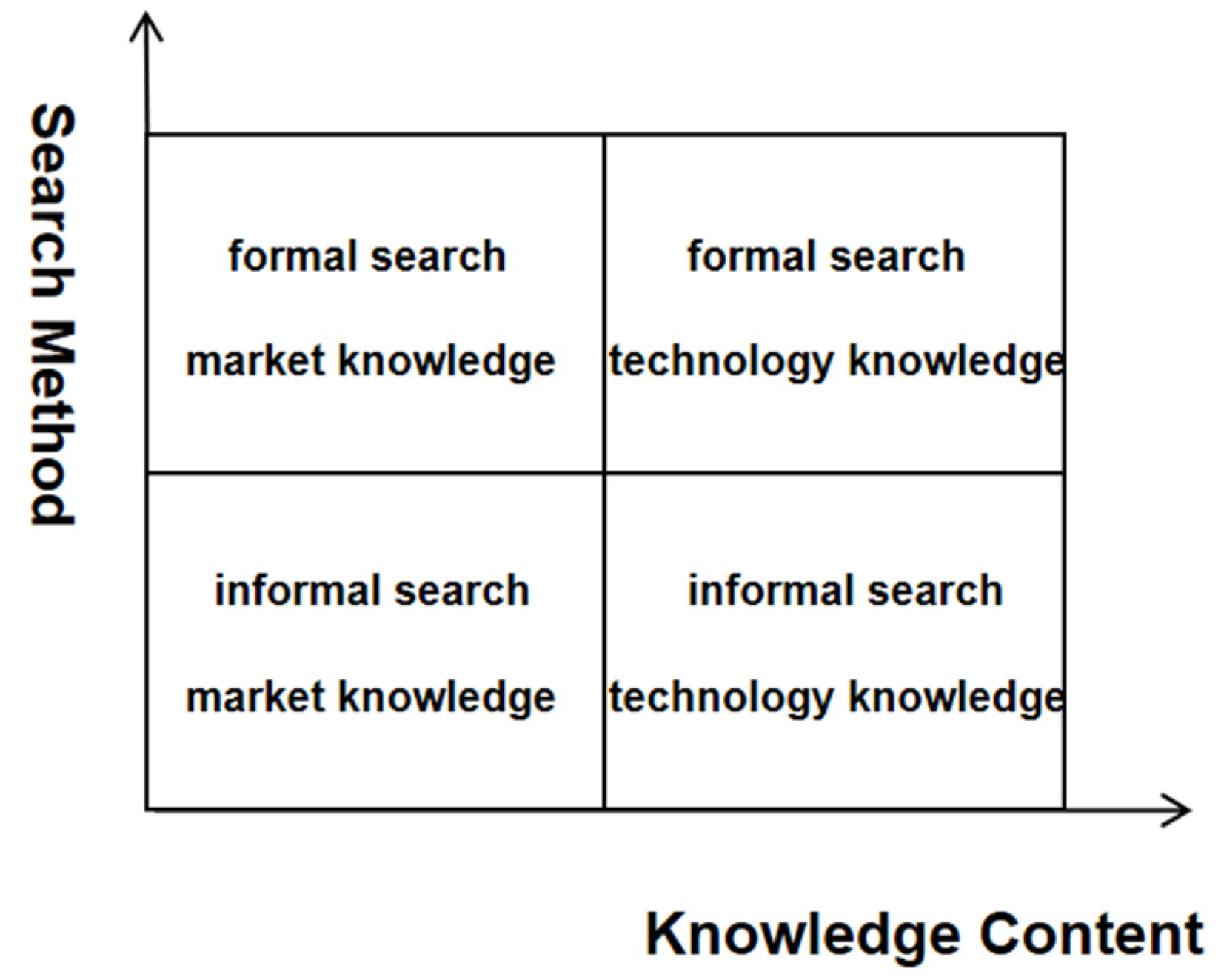

2.4. External Knowledge Search

2.5. Organizational Learning

2.6. Strategic Flexibility

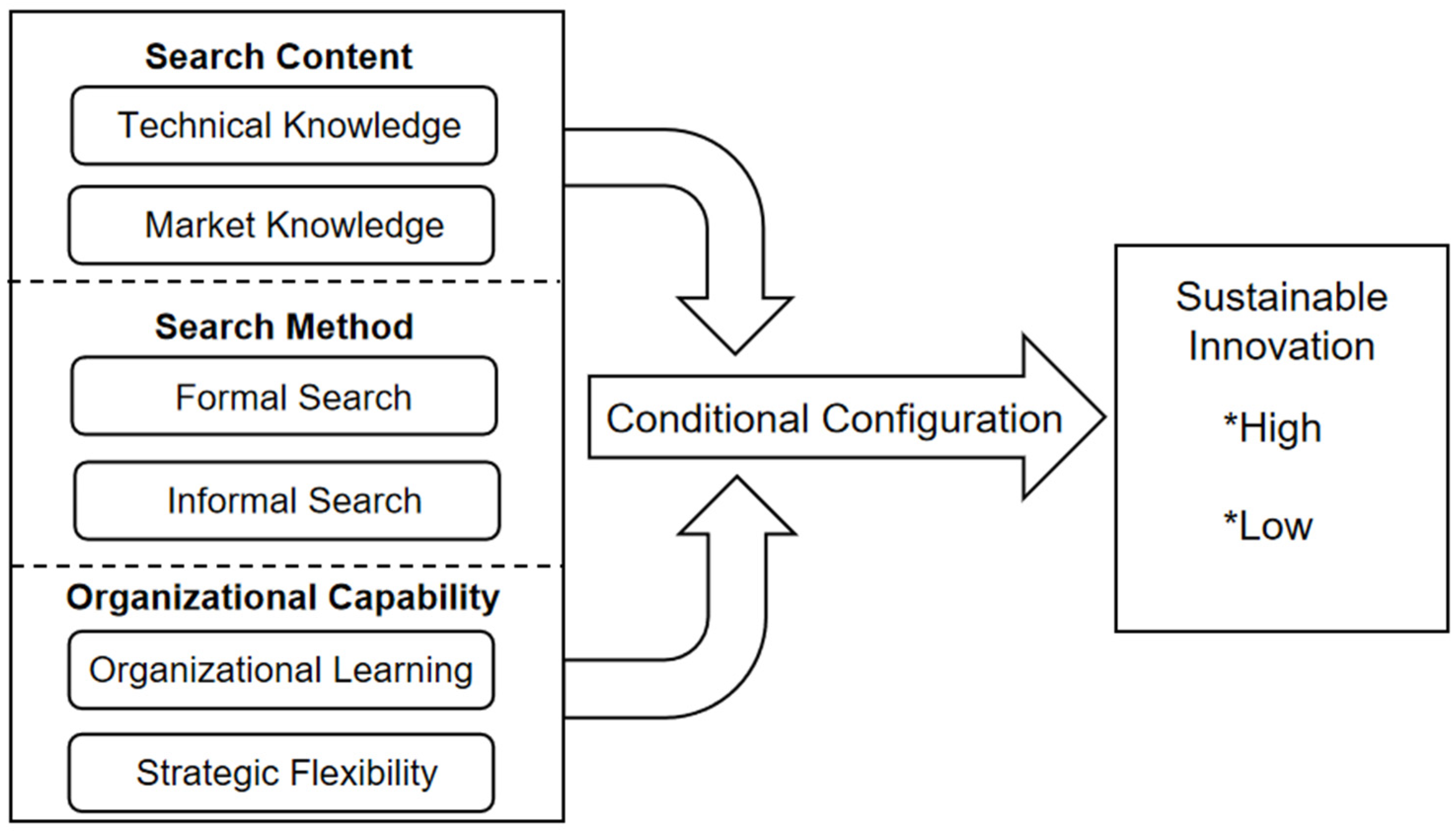

3. Model

4. Data and Methods

4.1. Research Methods

4.2. Samples and Data

4.3. Variables

- (1)

- Sustainable innovation (SI). This article mainly drew on the research of Story, Boso, and Cadogan [88] and Hansen and Birkinshaw [89], involving a total of 6 items such as the innovation ability of the enterprise and the satisfaction of the product or service. Examples include “We have a strong ability to innovate”, “Compared with competitors, our products or services have more advantages”, and so on. The Cronbach’s alpha of this variable was 0.803, and the AVE was 0.54, indicating that it reached acceptable standards in terms of reliability and validity.

- (2)

- External knowledge search. In terms of a technical knowledge search (TKS) and market knowledge search (MKS), this research referred to the research of Sofka and Grimpe [17] and Ki H and Jina [55]. The formal search (FS) and informal search (IS) are based on the research of Guo B and Guo JJ [18]. Examples include “We are good at seeking technical knowledge through purchasing technology, licensing, etc.”, “We are good at seeking market information such as new sales channels and marketing strategies from enterprises in the same industry through formal cooperation”, “We are good at imitating competitors in the same industry and improving technology”, and “We are good at seeking product or service-related market information from customers through informal communication”. The Cronbach’s alpha of each variable was 0.830, 0.827, 0.816, and 0.803, and the average was 0.40, 0.49, 0.45, and 0.54, indicating that the reliability and validity reached acceptable standards.

- (3)

- Organizational learning (OL). This article drew on the research of Morales et al. [90], involving five items including knowledge acquisition ability and knowledge sharing. Examples include “The new knowledge or skills we acquire can bring a competitive advantage to the company” and “We are good at sharing and communicating knowledge to improve our skills.” The Cronbach’s alpha of this variable was 0.772, and the AVE was 0.53, indicating that it reached acceptable standards in terms of reliability and validity.

- (4)

- Strategic flexibility (SF). This paper drew on the research of Zhou and Wu [15] and divided strategic flexibility into two dimensions—resource flexibility and coordination flexibility. Examples include “We flexibly allocate production resources to manufacture various products” and “We will effectively redeploy organizational resources to support the firm”. The Cronbach’s alpha of this variable was 0.791 and the AVE was 0.54, indicating that it reached acceptable standards in terms of reliability and validity.

5. Results

5.1. Data Calibration

5.2. Necessity Analysis

5.3. Causal Configuration Analysis

- (1)

- Content-driven path (TKS × MKS × OL × SF). This configuration path emphasizes the importance of external knowledge sources. Moreover, the consistency between the condition variables and sustainable innovation is between 0.7 and 0.9, see Table 4. Therefore, we believe these variables are sufficient conditions to affect sustainable innovation. First, new ventures applying this driving path emphasize the importance of technical knowledge and market knowledge in terms of resources. This is consistent with studies by Voss [93] and Sofka and Grimpe [17]. They believed that technical knowledge is a key factor driving product development and innovation [17,46]. The emergence of new technologies will promote the upgrading of products, so that enterprises can gain greater competitive advantages and occupy a higher market share [94]. However, focusing only on technical knowledge and ignoring market knowledge is not advisable. After the enterprise has mastered the relevant market development trend and demanded change information, it can obtain various technical knowledge required for business development in time to protect the existing market position [95]. Thus, new ventures promote sustainable innovation with the combined effect of technical knowledge and market knowledge. Second, new ventures that apply this driving path emphasize the importance of organizational learning and strategic flexibility in terms of capabilities. This is consistent with the results of Liao et al. [96] and Sanchez [97]. They believe that the level of learning ability determines the effect of knowledge utilization, and the application of new knowledge can enhance sustainable innovation among enterprises [96]. In addition, the enterprise has high strategic flexibility, can better integrate and allocate the internal resources, and can cope with the changing external environment [14,97]. To sum up, this configuration path can promote sustainable innovation in new ventures through the resources–capabilities integration.

- (2)

- Method-driven path (FS × IS × OL × SF). This configuration path emphasizes the importance of searching methods. Moreover, the consistency between the condition variables and sustainable innovation is between 0.7 and 0.9, see Table 4. Therefore, we believe these variables are sufficient conditions to affect sustainable innovation.

5.4. Robustness Test

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Management Enlightenment

- (1)

- New ventures should pay attention to external knowledge sources. It can be seen from this study that technical knowledge and market knowledge are the core to maintaining the sustainable innovation of startups. For them, there two main ways of acquiring knowledge, which are technological knowledge-dependent and market knowledge-dependent. In the technical knowledge-dependent type, technical knowledge is the core element, and enterprises need to cooperate with suppliers, universities, and research institutions to obtain the technical knowledge. In the market knowledge-dependent type, market knowledge is the core element, and enterprises need to obtain relevant market knowledge from organizations such as customers or competitors in order to change the existing business model or increase market share.

- (2)

- New ventures should pay equal attention to formal and informal searches. It can be seen from the above research that the use of formal and informal search methods by enterprises is also an important factor in maintaining competitiveness. Startups can quickly acquire a large amount of new knowledge through formal search methods, and the introduction of new production equipment or production lines and the employment of relevant technical personnel have made the inflow of knowledge more obvious. However, using informal search methods is equally important, because only through informal search methods can we obtain tacit knowledge or make tacit knowledge explicit, which is more conducive to sustainable innovation.

- (3)

- New ventures need to improve their organizational learning capabilities. To cope with the complex external environment, startups need to innovate continuously and develop into a learning organization. Looking at some leading enterprises of China, such as Ali, Tencent, and Huawei, we can see that their rapid development is inseparable from the learning and the formation of sustained competitive advantages. One step is to transform the acquired knowledge into the enterprise’s innovation. The second step is to strengthen mutual benefit and trust among organizations, promote knowledge exchange and communication, and increase their knowledge transfer and sharing. The third step is to identify and discover new opportunities through the generation of new knowledge, expand the business scale, and enhance the sustainable innovation of the enterprise.

- (4)

- New ventures need to improve their strategic flexibility. At present, the survival environment of startups is becoming increasingly turbulent. Measures to survive in this complex and changeable environment have become a primary factor in research. However, it is undoubtedly a good method to allocate resources flexibly and reorganize resources. First of all, startups should pay close attention to changes in the business environment and reduce market risks. Secondly, startups need to improve their management capabilities to increase the integration efficiency of internal and external resources. Finally, business managers should cultivate flexible strategic thinking and form organizational routines. In this way, startups can improve their strategic flexibility and strengthen their current operating conditions to maintain sustainable innovation.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foxon, T.; Pearson, P. Overcoming barriers to innovation and diffusion of cleaner technologies: Some features of a sustainable innovation policy regime. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, S148–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Tian, F.; Sun, X.; Zhang, D. The Effects of Entrepreneurship on the Enterprises’ Sustainable Innovation Capability in the Digital Era: The Role of Organizational Commitment, Person–Organization Value Fit, and Perceived Organizational Support. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.; Gomes, S.; Pacheco, R.; Monteiro, E.; Santos, C. Drivers of Sustainable Innovation Strategies for Increased Competition among Companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S.L. Value, rareness, competitive advantage, and performance: A conceptual-level empirical investigation of the resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 29, 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desa, G.; Basu, S. Optimization or Bricolage? Overcoming Resource Constraints in Global Social Entrepreneurship. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2013, 7, 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.B.; Ma, X.; Shi, Z.; Peng, S.B. How knowledge search affects the performance of reverse internationalization enterprises: The co-moderating role of causation and effectuation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 1105–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Brunswicker, S.; Majchrzak, A. Knowledge search breadth and depth and OI projects performance: A moderated mediation model of control mechanism. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 12, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.Y.; Lim, M.S.; Yoo, J.W. Ambidexterity in External Knowledge Search Strategies and Innovation Performance: Mediating Role of Balanced Innovation and Moderating Role of Absorptive CapacityJ. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, J.C.; Roldán, J.L.; Leal, A. From Entrepreneurial Orientation and Learning Orientation to Business Performance: Analysing the Mediating Role of Organizational Learning and the Moderating Effects of Organizational Size. Br. J. Manag. 2014, 25, 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L.; Miron-Spektor, E. Organizational Learning:From Experience to Knowledge. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, P.L.; Lee, D.Y.; Midgley, D. Organizational learning in high-technology purchase situations: The antecedents and consequences of the participation of external IT consultants. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R. Preparing for an uncertain future: Managing organizations for strategic flexibility. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1997, 27, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Wu, F. Technology Capability, Strategic Flexibility, and Product Innovation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 547–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Liu, Z.; Fu, L.; Ye, P. Investigate the role of distributed leadership and strategic flexibility in fostering business model innovation. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2019, 13, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofka, W.; Grimpe, C. Specialized search and innovation performance: Evidence across Europe. R&D Manag. 2010, 40, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Guo, J.J. Patterns of technological learning within the knowledge systems of industrial clusters in emerging economies: Evidence from China. Technovation 2011, 31, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S.; Duguid, P. Organizational Learning and Communities-of-Practice: Toward a Unified View of Working, Learning, and Innovation. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, D.; Sanz-Valle, R. Innovation, organizational learning, and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Searching high and low: What types of firms use universities as a source of innovation? Res. Policy 2004, 33, 1201–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Li, J. Knowledge search modes and innovation performance: The moderating role of strategic R&D orientation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. 2019, 31, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.P. Effectuation, opportunity shaping and innovation strategy in high-tech new ventures. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Adomako, S. The Effects of Knowledge Integration and Contextual Ambidexterity on Innovation in Entrepreneurial Ventures. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 127, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, J.; Newell, S.; Fernandez-Mesa, A.; Alegre, J. Depth and breadth of external knowledge search and performance: The mediating role of absorptive capacity. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 47, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, L.M.; Cooper, S.Y. External knowledge search, absorptive capacity and radical innovation in high-technology firms. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 34, 1453–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliasghar, O.; Rose, E.L.; Chetty, S. Where to search for process innovations? The mediating role of absorptive capacity and its impact on process innovation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 82, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, V.; Chaim, N. Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: A guide to qualitative comparative analysis. Int. J. Soc. Res. Method 2013, 16, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Crowther, A. Beyond high tech: Early adopters of open innovation in other industries. R&D Manag. 2006, 36, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Katila, R.; Ahuja, G. Something Old, Something New: A Longitudinal Study of Search Behavior and New Product Introduction. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 10, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuveloo, R.; Shanmugam, N.; Ai, P.T. The impact of tacit knowledge management on organizational performance: Evidence from Malaysia. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2017, 22, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, B.M.; Mcdougall, P.P. Defining International Entrepreneurship and Modeling the Speed of Internationalization. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 29, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlander, L.; Gann, D. How open is innovation? Res. Policy 2010, 39, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hippel, E. Comment on “Is open innovation a field of study or a communication barrier to theory development?”. Technovation 2010, 30, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, P.; Mortensen, B. Some immediate-but negative-effects of openness on product development performance. Technovation 2011, 31, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keupp, M.; Gassmann, O. Determinants and archetype users of open innovation. R&D Manag. 2009, 39, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Types of Competition and the Theory of Strategy: Toward an Integrative Framework. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm Resource and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muoz-Pascual, L.; Galende, J. Ambidextrous Knowledge and Learning Capability: The Magic Potion for Employee Creativity and Sustainable Innovation PerformanceJ. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I. The dynamic theory of knowledge creation. Organ Sci. 1994, 5, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belderbos, R.; Faems, D.; Leten, B.; Looy, B.V. Technological activities and their impact on the financial performance of the firm: Exploitation and exploration within and between firms. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2010, 27, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, N.H. The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Long Range Plan. 1996, 29, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanson, L. Creating knowledge: The power and logic of articulation. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2007, 16, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, B.; Zander, U. Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of Technology. Organ. Sci. 1992, 3, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, R.; Torsten, R. Uncertainty, pluralism, and the knowledge-based theory of the firm: From J.-C. Spender’s contribution to a socio-cognitive approach. Eur. Manag. J. 2013, 31, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunke, S.; Weerawardena, J.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R. The central role of knowledge integration capability in service innovation-based competitive strategy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 76, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.K.; Song, S.; Sambamurthy, V.; Lee, Y.L. Entrepreneurship, knowledge integration capability, and firm performance: An empirical study. Inform. Syst. Front. 2012, 14, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Spender, J.D. Making knowledge the basis of a dynamic theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial management in large organizations: Toward a theory of the (entrepreneurial) firm. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2016, 86, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makadok, R.A. Rational-Expectations Revision of Makadok’s Resource/Capability Synthesis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, A.J.; Opsahl, T.; George, G.; Gann, D.M. The Effects of Culture and Structure on Strategic Flexibility During Business Model Innovation. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Kang, J. How Do Firms Source External Knowledge for Innovation? Analysing Effects of Different Knowledge Sourcing Methods. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2009, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Kang, J. Do External Knowledge Sourcing Modes Matter for Service Innovation? Empirical Evidence from South Korean Service Firms. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2013, 31, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.L.; Chen, J.L. Knowledge management driven firm performance: The roles of business process capabilities and organizational learning. J. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 18, 1141–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashtari, A.; Salehi, J. A study on the effect of organizational learning on organizational performance with an emphasis on dynamic capacity. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Comp. 2014, 4, 1421–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Levitt, B.; March, J.G. Organizational learning. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1988, 14, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Lane, H.W.; White, R.E. An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, D.A.; March, J.G. The myopia of learning. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.Y.; Tscai, H. Dynamic capability, knowledge, learning, and firm performance. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2012, 25, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva, R.; Alegre, J. Organizational Learning Capability and Job Satisfaction: An Empirical Assessment in the Ceramic Tile Industry. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2010, 20, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.; Takahashi, A. Dynamic capabilities, organizational learning and ambidexterity in a higher education institution. Learn. Organ. 2019, 26, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Su, Z.; Liu, Y. Can strategic flexib ility help firms profit from product innovation? Technovation 2010, 30, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, L.; Liang, X.; Chen, Z.; Xu, W. Strategic flexibility, innovative HR practices, and firm performance A moderated mediation model. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 1335–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorondutse, A.H.; Arshad, D.; Alshuaibi, A.S. Driving sustainability in SMEs’ performance: The effect of strategic flexibility. J. Strategy Manag. 2021, 14, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Krause, D.R. Re-exploring the relationship between flexibility and the external environment. Oper. Res. 2004, 21, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, H.; Evans, S. Emerging organizational regimes in high technology firms: The bi-modal form. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 28, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkopf, L.; Nerkar, A. Beyond local search: Boundary: Panning, exploration, and impact in the optical disk industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkopf, L.; Almeida, P. Overcoming Local Search Through Alliances and Mobility. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Anthea, Z.Y.; Marjorie, L. Special Issue: Knowledge Search, Spillovers, and Creation in Emerging Markets. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2010, 6, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, J.J.; Poppo, L.; Zhou, K.Z. Relational mechanisms, formal contracts, and local knowledge acquisition by international subsidiaries. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, M.F.; Tarim, M.; Zaim, H.; Zaim, S.; Delen, D. Knowledge management and ERP: Complementary or contradictory? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, R.; Lo, W.; Tang, E.; Lau, A.K. Analysis of sources of innovation, technological innovation capabilities, and performance: An empirical study of Hong Kong manufacturing industries. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.M.R.; La Falce, J.L.; Marques, F.M.F.R.; De Muylder, C.F.; Silva, J.T.M. The relationship between organizational commitment, knowledge transfer and knowledge management maturity. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Känsäkoski, H. Information and knowledge processes as a knowledge management framework in health care: Towards shared decision making? J. Doc. 2017, 35, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozovic, D. Strategic flexibility: A review of the literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 2–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Ngai, E.; Moon, K. The effects of strategic and manufacturing flexibilities and supply chain agility on firm performance in the fashion industry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 259, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, R.; Westerlund, M.; Moeller, K. Strategic flexibility in open innovation—Designing business models for open source software. Eur. J. Market. 2012, 46, 1368–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, G. Does Business Model Innovation Enhance the Sustainable Development of New Ventures? Understanding an Inverted-U Relationship. Sustainability 2021, 13, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Su, Z.; Ahlstrom, D. Business model innovation: The effects of exploratory orientation, opportunity recognition, and entrepreneurial bricolage in an emerging economy. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2016, 33, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Set relations in social research: Evaluating their consistency and coverage. Polit. Anal. 2006, 14, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihoux, B.; Álamos-Concha, P.; Bol, D.; Marx, A.; Rezsöhazy, I. From niche to mainstream method? A comprehensive mapping of QCA applications in journal articles from 1984 to 2011. Polit. Res. Q. 2013, 66, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.W. Antecedents of franchise strategy and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, M.F.; Johnson, M.; Pointer, L.; Yankov, N. A fuzzy attractiveness of market entry (FAME) model for market selection decisions. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2013, 64, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denk, T.; Lehtinen, S. Contextual analyses with QCA-methods. Qual. Quant. 2014, 48, 3475–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, B.; Glaesser, J. Using case-based approaches to analyse large datasets: A comparison of Ragin’s fsQCA and fuzzy cluster analysis. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2010, 14, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, V.M.; Boso, N.; Cadogan, J.W. The Form of Relationship between Firm-Level Product Innovativeness and New Product Performance in Developed and Emerging Markets. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2015, 32, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T.; Birkinshaw, J. The Innovation Value Chain. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, F.; Antonio, J.; Verdú, J. Influence of personal mastery on organizational performance through organizational learning and innovation in large firms and SMEs. Technovation 2007, 27, 547–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D.; Schüssler, M. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) in entrepreneurship and innovation research—The rise of a method. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, M.J.; Jones, P.; Pickernell, D. Country-based comparison analysis using fsQCA investigating entrepreneurial attitudes and activity. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1271–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, G.B.; Voss, Z.G. Strategic Ambidexterity in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Implementing Exploration and Exploitation in Product and Market Domains. Organ. Sci. 2013, 24, 1459–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, A.K.; Jaworski, B. Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.H.; Fei, W.C.; Liu, C.T. Relationships between knowledge inertia, organizational learning and organization innovation. Technovation 2008, 28, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R. Strategic flexibility in product competition. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 16, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, V.M.; Sorenson, D.; Henchion, M.; Gellynck, X. Social capital and knowledge sharing performance of learning networks. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyka, A. Informal networking and industrial life cycles. Technovation 2000, 20, S0166–S4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wagemann, C. Reducing complexity in Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): Remote and proximate factors and the consolidation of democracy. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2010, 45, 751–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O.; Kourouthanassis, P.E.; Giannakos, M.N.; Chrissikopoulos, V. Explaining online shopping behavior with fsQCA: The role of cognitive and affective perceptions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, S.; Love, J.H.; Bonner, K. Firms’ knowledge search and local knowledge externalities in innovation performance. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Items | Quantity | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regional source | Entrepreneurial developed areas | 339 | 75.3% |

| Entrepreneurial underdeveloped areas | 111 | 24.7% | |

| Questionnaire Features | Questionnaires issued | 1036 | 52.6% |

| Questionnaire recovery | 545 | ||

| Questionnaire valid | 450 | 43.4% |

| Characteristics | Percentage | Characteristics | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Scale | ||

| 1–2 years | 18.9% | 1–20 | 3.1% |

| 3–5 years | 28.0% | 21–50 | 10.2% |

| 6–8 years | 53.1% | 51–100 | 25.6% |

| Industry | 101–200 | 16.0% | |

| Manufacturing | 32.9% | 201–500 | 21.6% |

| Information industry | 33.6% | 501–1000 | 11.3% |

| Retail industry | 9.1% | More than 1000 | 12.2% |

| Service industry | 15.6% | ||

| Other | 8.9% |

| Variable | Full Membership | Crossover Point | Non-Membership |

|---|---|---|---|

| SI | 6.1296 | 5.2937 | 4.4578 |

| TKS | 6.0416 | 5.3873 | 4.7330 |

| MKS | 6.1008 | 5.4087 | 4.7166 |

| FS | 6.0969 | 5.4894 | 4.8819 |

| IS | 6.0752 | 5.3030 | 4.5308 |

| OL | 6.2748 | 5.4818 | 4.6888 |

| SF | 6.1417 | 5.3515 | 4.5614 |

| Variable | High-SI | Low-SI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| TKS | 0.7744 | 0.7847 | 0.4509 | 0.4093 |

| ~TKS | 0.4169 | 0.4588 | 0.7627 | 0.7518 |

| MKS | 0.7635 | 0.7817 | 0.4546 | 0.4170 |

| ~MKS | 0.4307 | 0.4686 | 0.7620 | 0.7426 |

| FS | 0.7699 | 0.7818 | 0.4586 | 0.4172 |

| ~FS | 0.4260 | 0.4677 | 0.7601 | 0.7579 |

| IS | 0.7824 | 0.7849 | 0.4613 | 0.4145 |

| ~IS | 0.4164 | 0.4631 | 0.7605 | 0.7579 |

| OL | 0.7898 | 0.7741 | 0.4888 | 0.4291 |

| ~OL | 0.4175 | 0.4769 | 0.7426 | 0.7599 |

| SF | 0.8057 | 0.7877 | 0.4729 | 0.4141 |

| ~SF | 0.4007 | 0.4591 | 0.7577 | 0.7775 |

| Variable | High-SI | Low-SI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path1 | Path2 | Path1 | Path2 | |

| TKS |  |  |  | |

| MKS |  |  |  | |

| FS |  |  |  |  |

| IS |  |  | ||

| OL |  |  |  |  |

| SF |  |  |  |  |

| Consistency | 0.9167 | 0.9128 | 0.8767 | 0.8814 |

| Coverage | 0.5880 | 0.5786 | 0.5049 | 0.5043 |

| Solution consistency | 0.8978 | 0.8768 | ||

| Solution coverage | 0.6434 | 0.5188 | ||

= core causal condition (present), implying that the presence of the condition is crucial to the outcome;

= core causal condition (present), implying that the presence of the condition is crucial to the outcome;  = core causal condition (absent), suggesting that the absence of the condition is crucial to the outcome;

= core causal condition (absent), suggesting that the absence of the condition is crucial to the outcome;  = contributing causal condition (present), implying that the presence of the condition is not essential to the outcome;

= contributing causal condition (present), implying that the presence of the condition is not essential to the outcome;  = contributing causal condition (absent), suggesting that the absence of the condition is not essential to the outcome; blank spaces indicate that the presence or absence of the condition does not matter with regard to the outcome. “High-SI” represents the path to enhance sustainable innovation; “Low-SI” represents the path to reduce sustainable innovation.

= contributing causal condition (absent), suggesting that the absence of the condition is not essential to the outcome; blank spaces indicate that the presence or absence of the condition does not matter with regard to the outcome. “High-SI” represents the path to enhance sustainable innovation; “Low-SI” represents the path to reduce sustainable innovation.| Variable | High-SI | |

|---|---|---|

| Path1 | Path2 | |

| TKS |  |  |

| MKS |  | |

| FKS |  |  |

| IKS |  | |

| OL |  | |

| SF |  |  |

| Consistency | 0.9266 | 0.9370 |

| Coverage | 0.6398 | 0.6171 |

| Solution consistency | 0.9268 | |

| Solution coverage | 0.6657 | |

= core causal condition (present), implying that the presence of the condition is crucial to the outcome;

= core causal condition (present), implying that the presence of the condition is crucial to the outcome;  = contributing causal condition (present), implying that the presence of the condition is not essential to the outcome; blank spaces indicate that the presence or absence of the condition does not matter with regard to the outcome.

= contributing causal condition (present), implying that the presence of the condition is not essential to the outcome; blank spaces indicate that the presence or absence of the condition does not matter with regard to the outcome.Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Zhang, H. Driving Sustainable Innovation in New Ventures: A Study Based on the fsQCA Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095738

Liu Y, Zhang H. Driving Sustainable Innovation in New Ventures: A Study Based on the fsQCA Approach. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095738

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yu, and Hao Zhang. 2022. "Driving Sustainable Innovation in New Ventures: A Study Based on the fsQCA Approach" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095738

APA StyleLiu, Y., & Zhang, H. (2022). Driving Sustainable Innovation in New Ventures: A Study Based on the fsQCA Approach. Sustainability, 14(9), 5738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095738