Transaction-Specific Investment and Organizational Performance: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition and Clustering of Transaction-Specific Investment

2.2. Definition and Clustering of Organizational Performance

2.3. The Relationship between TSI and Organizational Performance

3. Hypotheses

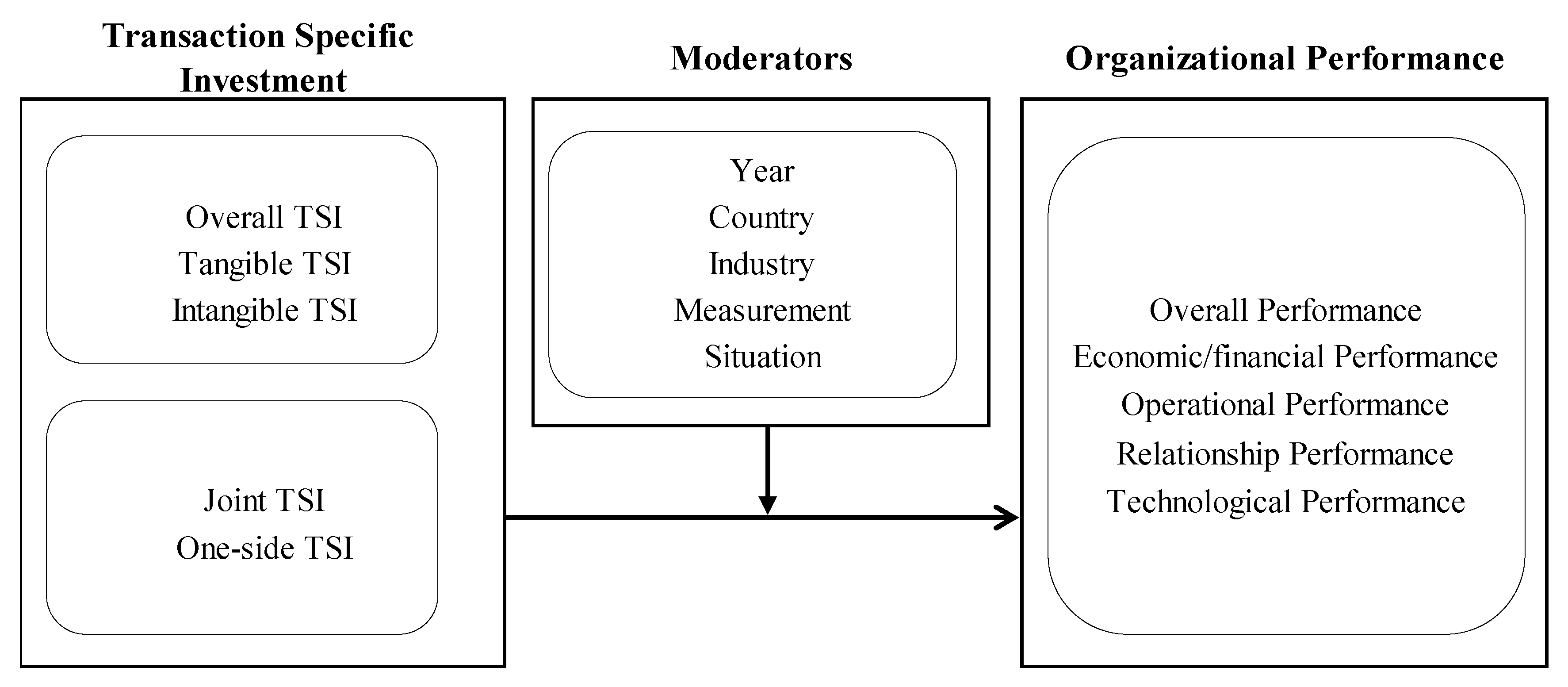

3.1. Conceptual Model

3.2. The Relationship between TSI and Organizational Performance

3.3. The Influence of Literature Characteristics on the Relationship between TSI and Organizational Performance

4. Research Methods

4.1. Literature Search and Sample Characteristics

4.2. Coding and Measurement

4.3. Mean Effect Size Estimation and Heterogeneity Test

4.4. Moderating Effect Analysis

5. Research Results

6. Discussion

7. Theoretical and Management Implications

7.1. Theoretical Significance

7.2. Management Implications

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, M.C.; Kang, M.P.; Chiang, J.K. Can a supplier benefit from investing in transaction-specific investments? A multilevel model of the value co-creation ecosystem perspective. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 25, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xue, J.; Li, Y. Transaction-specific investments in a supplier-distributor-supplier triad in China: Opportunism and cooperation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 1297–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.; Yu, T.; de Ruyter, K.; Chen, C.-F. Unfolding the impacts of transaction-specific investments: Moderation by out-of-the-channel-loop perceptions and achievement orientations. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 78, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, F. Matching governance mechanisms with transaction-specific investment types and supplier roles: An empirical study of cross-border outsourcing relationships. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, X. A taxonomy of transaction-specific investments and its effects on cooperation in logistics outsourcing relationships. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2019, 22, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H. Specialized supplier networks as a source of competitive advantage: Evidence from the auto industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehpour, M.; Shalehah, A.; Rahman, F.F.; Lin, K.-H. The Effect of Physician Communication on Inpatient Satisfaction. Healthcare 2022, 10, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. The economics of organization: The transaction cost approach. Am. J. Sociol. 1981, 87, 548–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, J.B.; John, G. The role of dependence balancing in safeguarding transaction-specific assets in conventional channels. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, M.R.; Venkatraman, N. Safeguarding investments in asymmetric interorganizational relationships: Theory and evidence. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Corsten, D.; Kumar, N. Do suppliers benefit from collaborative relationships with large retailers? An empirical investigation of efficient consumer response adoption. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, T. Governing buyer-supplier relationships through transactional and relational mechanisms: Evidence from China. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 27, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jap, S.D. Pie-expansion efforts: Collaboration processes in buyer-supplier relationships. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 461–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hoetker, G.; Mellewigt, T. Choice and performance of governance mechanisms: Matching alliance governance to asset type. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shervani, T.A.; Frazier, G.; Challagalla, G. The moderating influence of firm market power on the transaction cost economics model: An empirical test in a forward channel integration context. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.G.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr. Explaining interfirm cooperation and performance: Toward a reconciliation of predictions from the resource-based view and organizational economics. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 867–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.M.; Bode, C. Supplier relationship-specific investments and the role of safeguards for supplier innovation sharing. J. Oper. Manag. 2014, 32, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liping, Q.; Wei, G.; Xingyao, R. Impact of special investment of suppliers on long-term orientation of dealers. Manag. Rev. 2014, 26, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Claro, D.P.; Claro, P.B.O. The effects of trust, transaction specific investment and the moderating effect of information network on joint efforts in the Dutch Flower Industry. In Anais do IV Congresso Internacional de Economia e Gestão Agroalimentares—EGNA; Forum: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jap, S.D.; Anderson, E. Safeguarding interorganizational performance and continuity under ex post opportunism. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 1684–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jap, S.D. Perspectives on joint competitive advantages in buyer–supplier relationships. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2001, 18, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, R.; Mahapatra, S.; Arlbjørn, J.S. Impact of relational norms, supplier development and trust on supplier performance. Oper. Manag. Res. 2008, 1, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikeas, C.S.; Skarmeas, D.; Bello, D.C. Developing successful trust-based international exchange relationships. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.Y.; Hsieh, Y.J.; Hsiao, P.L. Examining the antecedents to inter-partner credible threat in the international joint ventures. Int. Bus. Res. 2012, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Y. Investing in guanxi: An analysis of interpersonal relation-specific investment (RSI) in China. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarmeas, D.; Robson, M.J. Determinants of relationship quality in importer–exporter relationships. Br. J. Manag. 2008, 19, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, A.; McEvily, B.; Perrone, V. Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vita, G.; Tekaya, A.; Wang, C.L. Asset specificity’s impact on outsourcing relationship performance: A disaggregated analysis by buyer-supplier asset specificity dimensions. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuehong, J.; Zhixiang, C.; Daoyin, S. Research on the relationship between supplier participation, specific investment and new product development performance. Manag. Rev. 2015, 27, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Crosno, J.L.; Dahlstrom, R. A meta-analytic review of opportunism in exchange relationships. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, S.S.; Wong, Y.; Liu, W. Asset specificity roles in interfirm cooperation: Reducing opportunistic behavior or increasing cooperative behavior? J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aulakh, P.S.; Kotabe, M. Antecedents and performance implications of channel integration in foreign markets. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1997, 28, 145–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jap, S.D.; Ganesan, S. Control mechanisms and the relationship life cycle: Implications for safeguarding specific investments and developing commitment. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Nickerson, J.A. Interorganizational trust, governance choice, and exchange performance. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 688–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jap, S.D. “Pie Sharing” in Complex Collaboration. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fadairo, M.; Lanchimba, C.; Windsperger, J. Network Form and Performance. The Case of Multi-Unit Franchising. The Case of Multi-Unit Franchising (March 2015); HAL Open Science: Lyon, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.R.; Crosno, J.L.; Dev, C.S. The effects of transaction-specific investments in marketing channels: The moderating role of relational norms. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarmeas, D.; Katsikeas, S.; Schlegelmilch, B. Drivers of Commitment and Its Impact on Performance in Cross-cultural Buyer-seller Relationships: The Importer’s Perspective. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 757–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, S.J. When to give up control of outsourced new product development. J. Mark. 2007, 71, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artz, K.W. Buyer-supplier performance: The role of asset specificity, reciprocal investments and relational exchange. Br. J. Manag. 1999, 10, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, J.B.; John, G. Alliances in industrial purchasing: The determinants of joint action in buyer-supplier relationships. J. Mark. Res. 1990, 27, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.L. Guanxi and organizational performance: A meta-analysis. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2012, 8, 139–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tungjitjarurn, W.; Suthiwartnarueput, K.; Pornchaiwiseskul, P. The Impact of supplier development on supplier performance: The role of buyer-supplier commitment, Thailand. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 4, 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ecel, A.; Ntayi, J.; Ngoma, M. Supplier development and export performance of oil-seed agro-processing firms in Uganda. Eur. Sci. J. 2013, 9, 469–491. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, I.C.L.; Ding, D.X.; Yip, N. Outcome-based contracts as new business model: The role of partnership and value-driven relational assets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Vesalainen, J.; Henneberg, S.; Naudé, P.; Ventresca, M.J. Enabling relationship structures and relationship performance improvement: The moderating role of relational capital. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambasivan, M.; Siew-Phaik, L.; Mohamed, Z.A.; Leong, Y.C. Factors influencing strategic alliance outcomes in a manufacturing supply chain: Role of alliance motives, interdependence, asset specificity and relational capital. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 141, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Humphreys, P.K.; Yeung, A.C.L.; Cheng, T.C.E. The impact of supplier development on buyer competitive advantage: A path analytic model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, A.; Bennett, D.; Sohal, A. Transaction attributes and buyer-supplier relationships in AMT acquisition and implementation: The case of Malaysia. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2009, 47, 2257–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Saleh, A. On importer trust and commitment: A comparative study of two developing countries. Int. Mark. Rev. 2010, 27, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griffith, D.A.; Lee, H.S.; Yeo, C.S.; Calantone, R. Marketing process adaptation: Antecedent factors and new product performance implications in export markets. Int. Mark. Rev. 2014, 31, 308–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Y.X.; Hung, S.W. How does supplier’s asset specificity affect product development performance? A relational exchange perspective. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2013, 8, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styles, C.; Patterson, P.G.; Ahmed, F. A relational model of export performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 39, 880–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulakh, P.S.; Kotabe, M.; Sahay, A. Trust and performance in cross-border marketing partnerships: A behavioral approach. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 1005–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, S.S.; Ngo, H. The role of trust and contractual safeguards on cooperation in non-equity alliances. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppo, L.; Zhou, K.Z.; Zenger, T.R. Examining the conditional limits of relational governance: Specialized assets, performance ambiguity, and long-standing ties. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 1195–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, M. An empirical investigation of the antecedents of sales force control systems. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtha, B.R.; Challagalla, G.; Kohli, A.K. The threat from within: Account managers’ concern about opportunism by their own team members. Manag. Sci. 2011, 57, 1580–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jap, S.D.; Anderson, E. Testing a life-cycle theory of cooperative interorganizational relationships: Movement across stages and performance. Manag. Sci. 2007, 53, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiss, A.M.; Kurland, N. Holding distribution channel relationships together: The role of transaction-specific assets and length of prior relationship. Organ. Sci. 1997, 8, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bercovitz, J.; Jap, S.D.; Nickerson, J.A. The antecedents and performance implications of cooperative exchange norms. Organ. Sci. 2006, 17, 724–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurcaylilar-Yenidogan, T.; Windsperger, J. Inter-organizational performance in the automotive supply networks: The role of environmental uncertainty, specific investments and formal contracts. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurcaylilar-Yenidogan, T.; Duden, S.; Sarvan, F. The role of relationship-specific investments in improving performance: Multiple mediating effects of opportunism and cooperation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 976–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poppo, L.; Zenger, T. Testing alternative theories of the firm: Transaction cost, knowledge-based, and measurement explanations for make-or-buy decisions in information services. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 853–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lado, A.A.; Dant, R.R.; Tekleab, A.G. Trust-opportunism paradox, relationalism, and performance in interfirm relationships: Evidence from the retail industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, M.J.; Gedajlovic, E.R. The Effects of External Sourcing on Performance: A Longitudinal Study of the Dutch Manufacturing Industry; Working Paper; Erasmus University Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Liu, Y.; Shun, B. How to improve the ability of contractors in innovative outsourcing projects—Path Analysis Based on special investment. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2015, 21, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, M.A. Strategic Attributions of Corporate social Responsibility and Environmental Management: The Business Case for Doing Well by Doing Good! In Sustainable Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, M.A. The employees’ state of mind during COVID-19: A self-determination theory perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Types |

|---|---|

| Williamson (1981) [8] | Location assets, physical assets, human assets. |

| Heide and John (1988) [9] | Human assets, product and process inputs. |

| Subramani and Venkatraman (2003) [10] | Tangible and intangible assets. |

| Business Performance | Content | Representative Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Performance | Overall Performance | Hoetker and Mellewigt (2009) [14] |

| Power Enhanced | Corsten, et al. (2005) [11] | |

| Economic/Financial Performance | Economic Performance | Corsten and Kumar (2005) [11] |

| Financial Performance | Shervani, Frazier, and Challagalla (2007) [15] | |

| ROA | Combs and Ketchen, Jr. (1999) [16] | |

| ROS Condition | Wagnera and Bode (2014) [17] | |

| Annual Sales | Qian et al. (2014) [18]; Claro et al. (2003) [19] | |

| Satisfaction with Financial Return | Jap and Anderson (2003) [20] | |

| Profit Performance | Jap (2001) [21] | |

| Operational Performance | Operational Performance | Narasimhan et al. (2008) [22] |

| Customer Performance | Katsikeas, Skarmeas, and Bello (2009) [23] | |

| Competitive Advantage Realized | Jap (1999) [13] | |

| Service Performance | Corsten and Kumar (2005) [11] | |

| Organizing and Managing Processes | Huang, Hsieh, and Hsiao (2012) [24] | |

| Relational Performance | Relationship Performance | G. Wang, X. Wang, and Y. Zheng (2014) [25] |

| Role Performance | Skarmeas and Robson (2008) [26] | |

| Trading Performance | Combs and Ketchen, Jr. (1999) [16] | |

| Satisfaction with Partner Performance | Zaheer, McEvily, and Perrone (1998) [27]; Vita, Tekaya, and Wang (2010) [28] | |

| Technological Performance | Scientific and Technological Capabilities | Huang, Hsieh, and Hsiao (2012) [24] |

| New Product Development Performance | Ji, Chen, and Sun (2015) [29] |

| Member | Representative Measurement | Representative Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Investment | (Likert Scale) Your company has dedicated time, effort, or/and money to Manufacturer X and its products. If your company switches manufacturers, those investments will disappear. Please indicate the extent to which your company has invested in the following areas to make the transaction with X go smoothly (1 for no investment, 7 for a large investment). For X, we change ours: 1. Product Requirements; 2. Sales Personnel; 3. Inventory and Distribution Procedures; 4. Policies; 5. Retail Strategy; 6. Information Systems; 7. Capital Equipment and Tools. | Sandy D. Jap and Shankar Ganesan (2000) [34] |

| Tangible Investment | (Likert Scale) Your company has invested heavily in specialized tools and equipment for your company and supplier relationships. | Ranjay Gulati and Jack A. Nickerson (2008) [35] |

| Intangible Investment | (Likert Scale) 1. In order to be more efficient, we spend a lot of time and energy to learn the operation process of the headquarters; 2. Our company’s sales staff spend a lot of time and energy to learn the special sales skills used by the headquarters; 3. We do a lot for the headquarters All tasks require cooperation and coordination between us and the staff of the headquarters; 4. As agents, we spend a lot of time and energy to help the headquarters develop the sales scope. | Jan B. Heide and George John (1988) [9] |

| Joint Investment | (Likert Scale) 1. If the relationship ends, they will waste knowledge specific to their relationship; 2. Any time either party changes buyers or suppliers, their investment in the existing relationship will be lost. | Jap (2001) [36] |

| Overall Performance | (Likert Scale) Enterprise performance is measured through the following aspects: 1. Administrative cost savings; 2. System growth; 3. Better distribution of products and services for customer needs; 4. More effective general and divisional coordination; 5. Cost reduction; 6. Increased production; 7. Improved innovation capabilities; 8. Savings in coordination and control costs; 9. Improved product quality; 10. Increased profits. | Fadairo, Lanchimba, and Windsperger (2015) [37] |

| Economic/ financial Performance | (Likert Scale) Please rate your company’s financial performance compared to your competitors: 1. Our company’s return on sales (ROS) last year; 2. Our company’s average annual return on sales over the past three years; 3. Our company’s return on sales growth/trend over the past three years. | Stephan M. Wagnera and Christoph Bode (2014) [17] |

| Operational Performance | (Likert Scale) Compared to your direct competitors, how does your company perform in the following areas? 1. Competitive position; 2. Customer resources; 3. Market share; 4. Access to new markets. | Brown, Crosno, and Dev (2009) [38] |

| Relational Performance | (Likert Scale) 1. Our company’s relationship with this supplier is productive; 2. Our company’s time and effort for this relationship is worthwhile; 3. Our company’s relationship with this supplier is very effective; 4. Our company’s relationship with this supplier is rewarding. | Skarmeas, Katsikeas, and Schlegelmilch (2002) [39] |

| Technological Performance | (Likert Scale) 1. The technology is highly innovative; 2. The contractor has shown great innovation in his work; 3. The technology integrates a lot of new knowledge and discoveries; 4. The technology will make a great contribution to the improvement of our product functions; 5. This technology will make a great contribution to the competitiveness of our products; 6. This technology will make a great contribution to the profitability of our products. | Stephen J. Carson (2007) [40] |

| British Journal of Management (n = 2) |

| Artz (1999) [41] |

| Skarmeas and Robson (2008) [26] |

| European Journal of Business and Management (n = 1) |

| Tungjitjarurn, Suthiwartnarueput, and Pornchaiwiseskul (2012) [44] |

| European Scientific Journal (n = 1) |

| Ecel, Ntayi, and Ngoma (2013) [45] |

| Faculdade de Economia (n = 1) |

| Claro and Claro (2003) [19] |

| Industrial Marketing Management (n = 3) |

| Ng, Ding, and Yip (2013) [46] |

| Wang, Wang, and Zheng (2014) [25] |

| Kohtamäki, Vesalainen et al. (2012) [47] |

| Int. J. Production Economics (n = 2) |

| Sambasivan, Siew-Phaik, Mohamed, and Leong (2013) [48] |

| Li, Humphreys, Yeung, and Cheng (2012) [49] |

| International Business Research (n = 1) |

| Huang, Hsieh, and Hsiao (2012) [24] |

| International Journal of Production Research (n = 1) |

| Abd Rahman, Bennett, and Sohal (2009) [50] |

| International Marketing Review (n = 2) |

| Bianchi, and Saleh (2010) [51] |

| Griffith, Lee, Yeo, and Calantone (2014)-[52] |

| Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing (n = 1) |

| Yen and Hung (2013) [53] |

| Journal of Business Research (n = 2) |

| Lui, Wong, and Liu (2009) [31] |

| Glauco De Vita, Arafet Tekaya, and Catherine L. Wang (2010) [28] |

| Journal of International Business Studies (n = 5) |

| Preet S. Aulakh and Masaaki Kotabe (1997) [33] |

| Styles, Patterson, and Ahmed (2008) [54] |

| Aulakh, Kotabe, and Sahay (1996) [55] |

| Katsikeas, Skarmeas, and Bello (2009) [23] |

| Skarmeas, Katsikeas, and Schlegelmilch (2002) [39] |

| Journal of Management (n = 1) |

| Lui and Ngo (2004) [56] |

| Journal of Management Studies (n = 1) |

| Poppo, Zhou, and Zenger (2008) [57] |

| Journal of Marketing (n = 4) |

| Heide and John (1988) [9] |

| Carson (2007) [40] |

| Krafft (1999) [58] |

| Corsten and Kumar (2005) [11] |

| Journal of Marketing Research (n = 3) |

| Jap (1999) [13] |

| Heide and John (1990) [9] |

| Jap & Ganesan (2000) [34] |

| Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice (n = 1) |

| Brown, Crosno, and Dev (2009) [38] |

| Journal of Operations Management (n = 2) |

| Wagner and Bode (2014) [17] |

| Liu, Luo, and Liu (2009) [12] |

| Management Science (n = 3) |

| Murtha, Challagalla, and Kohli. (2011) [59] |

| Jap and Anderson (2003) [20] |

| Jap and Anderson (2007) [60] |

| Operations Management Research (n = 1) |

| Narasimhan, Mahapatra, and Arlbjørn (2008) [22] |

| Organization Science (n = 4) |

| Weiss, and Kurland (1997) [61] |

| Gulati and Nickerson (2008) [35] |

| Zaheer, McEvily, and Perrone (1998) [27] |

| Bercovitz, Jap, and Nickerson (2006) [62] |

| Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences (n = 2) |

| Gurcaylilar-Yenidogan and Windsperger (2014) [63] |

| Gurcaylilar-Yenidogan, Duden, and Sarvanc (2013) [64] |

| Strategic Management Journal (n = 5) |

| Poppo and Zenger (1998) [65] |

| Hoetker and Mellewigt (2009) [14] |

| Combs and Ketchen. (1999) [16] |

| Lado, Dant, and Tekleab (2008) [66] |

| Tasadduq A. Shervani, Gary Frazier, and Goutam Challagalla (2007) [15] |

| Supply Chain Management (n = 1) |

| Miguel Hernández-Espallardo, Augusto Rodr íguez-Orejuela, and Manuel Sánchez-Pérez (2010) |

| Working Papers and Unpublished Papers (n = 2) |

| Mol and Gedajlovic (2015) [67] |

| Fadairo, Lanchimba, and Windsperger (2015) [37] |

| Business Review (n = 3) |

| Qian, Gao, and Ren (2014) [18] |

| Ji, Chen, and Sun (2015) [29] |

| Qian and Ren (2010) [11] |

| Economic Management Journal (n = 2) |

| Shou (2012) [13] |

| Ren, Zhu, and Qian (2012) [12] |

| Science and Technology Management Research (n = 1) |

| Zheng, Liu, and Sun (2015) [68] |

| Varibles | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TSI_Tangible | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | TSI_Intangible | −0.177 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | TSI_Joint | 0.014 | −0.123 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | Perf_Overall | 0.123 | 0.245 ** | 0.106 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 5 | Perf_Financial | −0.057 | 0.099 | −0.067 | −0.192 * | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Perf_Operational | 0.034 | −0.115 | 0.021 | −0.181 * | −0.198 * | 1 | |||||||||||

| 7 | Perf_Relationship | −0.047 | −0.190 * | −0.016 | −0.403 ** | −0.440 ** | −0.416 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 8 | Perf_Technology | −0.059 | 0.06 | −0.062 | −0.085 | −0.093 | −0.088 | −0.195 * | 1 | |||||||||

| 9 | Year | 0.195* | 0.171 | −0.159 | 0.231 ** | −0.146 | −0.04 | −0.077 | 0.135 | 1 | ||||||||

| 10 | Measurement | −0.016 | 0.109 | −0.026 | −0.017 | 0.413 ** | 0.043 | −0.303 ** | −0.074 | −0.127 | 1 | |||||||

| 11 | Country1_Developing | 0.214 * | 0.046 | −0.017 | 0.061 | −0.129 | −0.112 | 0.098 | 0.098 | 0.338 ** | −0.065 | 1 | ||||||

| 12 | Country1_Developed | −0.075 | 0.145 | −0.045 | −0.045 | 0.1 | 0.019 | −0.037 | −0.052 | −0.015 | 0.102 | -0.536 ** | 1 | |||||

| 13 | Industry_Manufacturing | 0.054 | −0.142 | 0.142 | −0.259 ** | −0.085 | −0.008 | 0.193 * | 0.161 | −0.105 | −0.057 | 0212 * | −0.142 | 1 | ||||

| 14 | Industry_Service | −0.01 | 0.210 * | −0.09 | 0.227 * | 0.077 | −0.059 | −0.11 | −0.171 | 0.01 | 0.086 | −0.192 * | 0.257 ** | −0.705 ** | 1 | |||

| 15 | Situation_B2S | −0.172 | 0.142 | −0.244 ** | −0.106 | −0.064 | −0.076 | 0.177 * | 0.006 | 0.002 | −0.14 | −0.081 | 0.134 | 0.031 | −0.048 | 1 | ||

| 16 | Situation_S2B | 0.153 | −0.004 | −0.186 * | 0.145 | −0.042 | 0.227 * | −0.261 ** | 0.06 | 0.133 | −0.001 | 0.002 | −0.105 | 0.075 | −0.043 | −0.479 ** | 1 | |

| 17 | r | 0.146 | −0.163 | 0.076 | 0.111 | −0.136 | 0.048 | −0.033 | 0.056 | 0.210 * | −0.108 | 0.437 ** | −0.391 ** | 0.154 | −0.341 ** | −0.105 | 0.075 | 1 |

| 18 | Mean | 0.079 | 0.268 | 0.087 | 0.15 | 0.173 | 0.157 | 0.48 | 0.039 | 0.693 | 0.118 | 0.205 | 0.528 | 0.409 | 0.417 | 0.386 | 0.268 | 0.168 |

| 19 | SD | 0.27 | 0.445 | 0.282 | 0.358 | 0.38 | 0.366 | 0.502 | 0.195 | 0.463 | 0.324 | 0.405 | 0.501 | 0.494 | 0.495 | 0.489 | 0.445 | 0.259 |

| Relationship | K | SE | 95% CI | QH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Overal TSI→Performance | 127 | 0.121 | 0.120 | 0.005 | 0.111 | 0.130 | 3491.592 * |

| 1. Year (1988–2004) | 39 | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.008 | 0.028 | 0.060 | 633.709 * |

| 2. Year (2005–2015) | 88 | 0.159 | 0.158 | 0.006 | 0.146 | 0.169 | 2727.492 * |

| 3. Measurement (objective) | 112 | 0.126 | 0.125 | 0.005 | 0.116 | 0.135 | 3343.191 * |

| 4. Measurement (subjective) | 15 | 0.083 | 0.083 | 0.014 | 0.056 | 0.110 | 139.876 * |

| 5. Country (developing) | 26 | 0.461 | 0.431 | 0.014 | 0.403 | 0.459 | 346.932 * |

| 6. Country (developed) | 67 | 0.084 | 0.084 | 0.006 | 0.073 | 0.096 | 1680.844 * |

| 7. Indurstry (manufactring) | 52 | 0.202 | 0.199 | 0.009 | 0.182 | 0.216 | 950.327 * |

| 8. Indurstry (service) | 53 | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.006 | 0.029 | 0.053 | 1760.934 * |

| 9. Context (buyer invest on supplier) | 49 | 0.113 | 0.112 | 0.007 | 0.098 | 0.127 | 1060.732 * |

| 10. Context (supplier invest on buyer) | 34 | 0.192 | 0.189 | 0.012 | 0.165 | 0.213 | 324.403 * |

| Intangible TSI→Overal performance | 34 | 0.068 | 0.068 | 0.009 | 0.051 | 0.085 | 743.074 * |

| Tangible TSI→Overal performance | 10 | 0.325 | 0.314 | 0.021 | 0.273 | 0.356 | 337.523 * |

| One-side TSI→Overal performance | 116 | 0.112 | 0.111 | 0.005 | 0.102 | 0.121 | 3340.298 * |

| Joint TSI→Overal performance | 11 | 0.272 | 0.266 | 0.020 | 0.227 | 0.304 | 89.568 * |

| Overal TSI→Overal performance | 19 | −0.069 | −0.069 | 0.013 | −0.094 | −0.044 | 767.862 * |

| Overal TSI→Economic/finacial performance | 22 | 0.122 | 0.121 | 0.010 | 0.101 | 0.141 | 147.786 * |

| Overal TSI→Operational performance | 20 | 0.144 | 0.143 | 0.012 | 0.119 | 0.167 | 205.038 * |

| Overal TSI→Relational performance | 61 | 0.160 | 0.159 | 0.007 | 0.145 | 0.172 | 2056.467 * |

| Overal TSI→Technological performance | 5 | 0.315 | 0.305 | 0.038 | 0.230 | 0.380 | 36.334 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Wang, L. Transaction-Specific Investment and Organizational Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5395. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095395

Zhang L, Zeng Q, Zhang S, Li S, Wang L. Transaction-Specific Investment and Organizational Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5395. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095395

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Leinan, Qingyan Zeng, Silin Zhang, Shuqin Li, and Liang Wang. 2022. "Transaction-Specific Investment and Organizational Performance: A Meta-Analysis" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5395. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095395

APA StyleZhang, L., Zeng, Q., Zhang, S., Li, S., & Wang, L. (2022). Transaction-Specific Investment and Organizational Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability, 14(9), 5395. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095395