Abstract

Across the world, policies and measures are being developed and implemented to reduce the risks of climate change and adapt to its current and projected adverse effects. The Paris Agreement established the global stocktake to evaluate the collective progress made on adaptation. Nevertheless, various challenges still exist when evaluating adaptation progress, among which is the lack of standard definitions to support evaluation efforts. Therefore, we investigated the views of experts regarding the definitions of adaptation given by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the definition of successful adaptation by Doria et al., with a focus on Latin America. Using the Delphi method, we obtained relevant knowledge and perspectives. As a result, we identified a high level of consensus (85%) among the experts regarding the IPCC’s definition of climate adaptation. However, there was no consensus on the definition of successful adaptation. For both definitions, we present the elements on which the experts agreed and disagreed, as well as the proposed elements that could improve the definitions to support adaptation evaluation efforts. Additionally, we introduce a list of criteria and indicators that could improve the evaluation of adaptation at different management levels and facilitate the aggregation of information on adaptation progress.

1. Introduction

Currently, natural and human systems are experiencing the adverse effects of more than 1 °C of mean global warming compared to pre-industrial levels [,]. Therefore, there is a need for ecosystems and societies to adapt to the changing climate conditions. Policies and measures to adapt to and reduce climate-change-imposed risks are therefore being developed and implemented at different scales and in different settings across the globe [,,]. However, due to the inherent complexities of adaptation, it is not easy to assess whether the climate adaptation measures implemented are actually helping ecosystems and societies to adapt successfully. Context-specificity, meaning that what is identified as progress or successful adaptation by one community may not be recognized as such by another, is one of the key adaptation complexities involved [,,,,,,,,,,,].

Acknowledging such complexities, an important prerequisite to conducting a meaningful assessment of adaptation success is to have a sound understanding of what adaptation means. The IPCC’s Working Group II [] (p. 118) is the most commonly cited definition of climate adaptation: “The process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects. In human systems, adaptation seeks to moderate or avoid harm or exploit beneficial opportunities. In some natural systems, human intervention may facilitate adjustment to expected climate and its effects“. In the realm of successful adaptation an example is given by Doria et al. [] (p. 817): “successful adaptation is any adjustment that reduces the risks associated with climate change, or vulnerability to climate change impacts, to a predetermined level, without compromising economic, social, and environmental sustainability”.

Despite these and other academic efforts to define climate adaptation (e.g., [,]) and successful adaptation (e.g., [,,]), the literature still shows a limited understanding of both. For instance, scholars identify the IPCC’s definition of adaptation as being not “operational”, since it does not include specific elements that would allow measuring the progress obtained through adaptation measures [,,,]. Similarly, to the discussion on a standard definition for adaptation, the issue of successful adaptation has also been identified as an adaptation research priority [,,].

Current climate adaptation research is even more limited for the case of vulnerable regions in the Global South [,]. One of these regions is Latin America [,,,], which has been identified as “highly exposed, vulnerable and strongly impacted by climate change” [], with the level of implementation of adaptation lagging behind the actual needs [,,]. Equally, there are insufficient financial resources [,], as well as scarce information on the feasibility, and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of adaptation options in the region [,,]. Overcoming these informational and financial limits is essential for the adequate funding and implementation of adaptation priorities [].

Moreover, it is crucial to note that the scope of the adaptation policies and monitoring and evaluation frameworks used in Latin America is limited to climate impact drivers, excluding social and economic aspects that influence the effectiveness of adaptation measures [,]. Among the barriers limiting adaptation policy monitoring and assessment in the region are the lack of a clear delimitation of adaptation policies, the lack of indicators to assess the effectiveness of adaptation measures, and the lack of mechanisms with which to track adaptation [].

The limitations on monitoring and evaluation in Latin America fall short of the ambitions for adaptation set at the global policy level. The global stocktake (GST) and global goal on adaptation (GGA) were established by the Paris Agreement within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The GST serves as the overarching mechanism with which to assess collective progress on mitigation, adaptation, and climate finance based on national reporting instruments. As part of the GST and in the realm of adaptation, the GGA includes a reduction in vulnerability, increase in resilience, and increase in adaptive capacities [].

However, most of the literature on the implementation and progress of adaptation is related to measures implemented at the local level. This and the circumstances of adaptation as they are at present, for example, in Latin America, present challenges at other levels of management in terms of data availability and comparable and meaningful indicators or proxies to measure adaptation, especially from the local to the global scale [].

The first GST is planned for 2023, and it will also review the overall progress made concerning the GGA []. However, how can the impact of adaptation policies and interventions be measured or assessed if we do not have a common definition of adaptation or what successful adaptation entails? Moreover, how can we use information produced at local or subnational levels at the international (aggregated) level to inform the GST?

To contribute to the establishment of definitions of climate adaptation and successful adaptation, especially one that is applicable to different contexts and local specificities across the globe, it is pivotal that different perspectives be taken into account []. Therefore, we investigated the views of Latin American experts on the definition of adaptation according to the IPCC [], as well as those on the definition of successful adaptation developed by Doria et al. [].

We used the Delphi method, a “group facilitation technique”, which utilizes an iterative, multistage process, to transform opinion into group consensus [] (p. 1008). The method has been used in a wide range of sectors and for multiple objectives, including for aspects relating to climate change adaptation (e.g., [,,,,,]). The method has already been applied by Doria et al. [] in their development of their own definition of successful adaptation. The Delphi method allowed us to identify the perspectives obtained from a heterogeneous panel of Latin American adaptation experts. The method facilitated a co-production process between the researchers and experts by identifying elements of agreement and disagreement. In this way, this method also facilitated the identification of ways to improve the existing definitions. Additionally, the method let us identify a list of criteria and indicators that could be used for aggregating information on adaptation from the local level to the global level to inform the GST.

With our work, we aim to provide guidance on (1) the aspects of definitions of adaptation and successful adaptation to foster their general operability and their use in adaptation success assessment, and (2) criteria and indicators that could support efforts to aggregate information on adaptation progress, for example, in the frame of the GST. To strengthen the respective research focusing on the Global South we apply our efforts to the case of Latin America.

2. Why Are Definitions for Climate Adaptation Important?

Definitions aim to establish and clarify what a word entails. They help to avoid ambivalences or ambiguities. Bassett and Folgemann [] (p. 51) highlight that “how we think and talk about adaptation matters in current and future debates on transformative climate action”. Until recently, adaptation to climate change was considered a nascent policy and research field [,,]. However, new literature shows that climate adaptation research is rapidly increasing in volume and diversifying [,,]. Moreover, following the establishment of the GST, research related to adaptation assessment has gained prominence.

Nevertheless, the definition of climate adaptation and, more importantly, what is considered successful adaptation, remains a challenge. Moreover, the usefulness of a definition of successful adaptation is being debated (e.g., []). Questions remain about what it is necessary to evaluate (what is adaptation?) [,,,] and what we can classify as progress or success (what is successful adaptation?) [,,,,,].

Recent literature speaks of climate adaptation as a public good [], as a public goal [], and as an investment []. Moreover, is seen as a process, an adjustment, or an outcome [,]. All those perspectives highlight the need to evaluate adaptation measures, especially in light of the limited financial resources available, the global policies in place, and the risk of maladaptation [,,,,]. The questions regarding the definition of adaptation and successful adaptation are relevant to all levels where the planning, design, and implementation of adaptation take place. However, there might be “no easy or political answers” [] (p.1), underpinning the need for a profound scientific understanding of what adaptation and its success entail.

As part of a wider debate, there are discussions on the need to differentiate adaptation from development [,,], as well as discussions about whether adaptation outcomes should be additional or complementary to those obtained from development interventions alone [,].

According to Moser and Boykoff [], investigating successful adaptation achieves the following goals: communication and public engagement, deliberate planning and decision-making, improved fit with other policy goals, justification of adaptation expenditures, improved accountability, and support for learning and adaptive management.

Regarding the assessment of adaptation measures and the aggregation of relevant information, the UNFCCC guides policies and actions undertaken at different management levels. In this regard, Magnan and Ribera [] (p. 1282) find it “crucial to overcome the intuitive and subjective understanding of adaptation”. The establishment of the GST as part of the Paris Agreement reflects and responds to the need for a better overview of how well or how successfully we adapt to climate change. However, how do we arrive at a reliable overview? Magnan [] indicates the need to develop metrics, which must comply with two characteristics: the consideration of context-dependent aspects (“national circumstances”) and allowing for the aggregation of information from the local through to the global level.

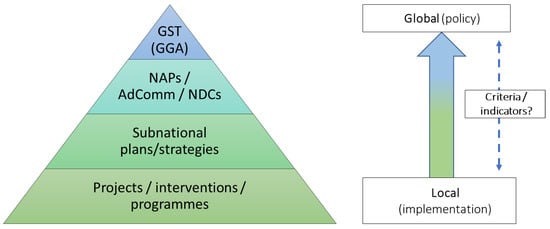

The UNFCCC already recognizes the multiple dimensions where adaptation actions or interventions take place []. Despite this, much of the literature describes adaptation as a “local” issue []. As a result, monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks are mainly developed for use at the local level (e.g., for a community or project/program) []. Likewise, the GST’s evaluation of adaptation progress is based on national assessments, and accordingly most efforts to inform the GST focus on the national level (e.g., [,,,,]). However, adaptation and reporting on adaptation progress also need to be considered as part of broader subnational, national, regional, and global mechanisms, such as the GST [] (see Figure 1). Nevertheless, there are also limits to an aggregated view of adaptation, as not all metrics can be used at all levels [].

Figure 1.

Aggregation of information on adaptation progress (GST: global stocktake; GGA: global goal on adaptation; NAPs: national adaptation plans; AdComm: adaptation communications; NDCs: national determined contributions).

In addition to the disconnection between the levels where adaptation policies are developed and actions implemented, most M&E frameworks developed for adaptation focus on providing accountability. This approach aligns with the need to guarantee that the limited resources available for adaptation are invested efficiently []. However, it does not provide guidance on, for example, the goals of vulnerability reduction or how to increase resilience [,]. Policymakers and practitioners face this type of challenge when evaluating and aggregating information on adaptation progress, together with those related to context, definitions chosen, and the availability of information [,,].

3. Methodology

3.1. The Delphi Method

The Delphi method is a versatile and valuable social research technique [,,]. The key characteristics of the Delphi method are that it is an iterative process between rounds of questionnaires that guarantees anonymity, has controlled feedback, and provides a statistical response [,].

The development of a Delphi exercise does not require face-to-face meetings. Instead, it allows reaching consensus through rounds of questionnaires, which are later analyzed and fed back to the panel members (experts) [,]. Each round of questionnaire answers serves as the basis for the next. As a result, direct interaction between experts is limited. This last aspect has been identified as a limitation of the method, as limited interactions could also imply that meaningful exchange within the expert group is absent from the process []. Nevertheless, this method allows the identification of the elements of agreement, level of consensus, and hierarchization among the different aspects that a group of experts evaluates.

The anonymity allowed by the Delphi method helps with the co-production of knowledge by avoiding issues of power and prestige between the experts, which could affect the co-production process []. The questionnaire and reports summarize the information and arguments given by the experts. It is necessary for the coordinating team to have strong abilities to analyze and extract the views from the experts [].

Another characteristic of the Delphi method is that it does not rely on a random or representative sample. Thus, the results obtained through the method represent only the professional opinion of those experts who participate in the exercise []. Additionally, reaching consensus might not necessarily mean that the correct answer has been found [,]. However, the results obtained can be used to further deepen the debate around the issue under study [].

3.2. Implementation Framework

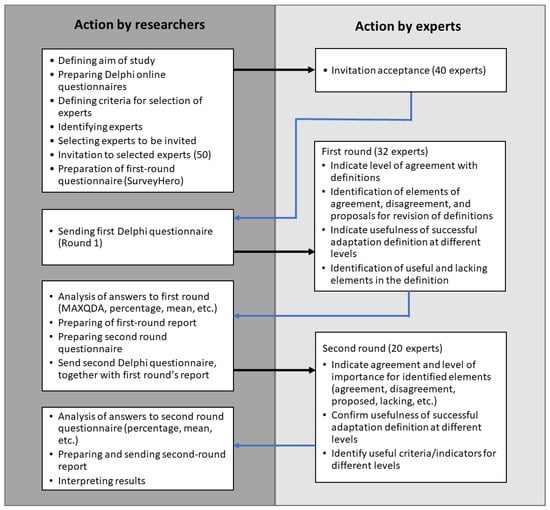

Based on the information presented previously, this section describes the process and steps we followed to implement the Delphi method in our research. Figure 2 summarizes the actions taken by the researchers (left) and the actions taken by the members of the panel of experts (right). The black and blue arrows represent their interactions.

Figure 2.

Summary of the steps, methods, and measures taken (adapted from []).

3.2.1. Selection of Experts and Communication

Experts are “informed individuals” and “specialists in their field” [] (p. 196). Considering that adaptation policies and implementation are developed at different scales and by different actors [,], we aimed to gather different perspectives on definitions of adaptation and successful adaptation from a heterogeneous panel of Latin American climate adaptation experts.

We identified a pool of 77 professionals working in academia, non-governmental organizations, and governmental dependencies designing and implementing adaptation actions. A total of 50 out of the 77 identified professionals were invited by e-mail to participate in the panel as experts. Out of the 50 invitees, 40 experts (80%) accepted the invitation. The selection was based on the experts’ publications, known experience, and professional networks. Of the 40 invited, 32 participated in the first round and 20 in the second. This decrease in the experts’ participation between both rounds is reported as a common situation in Delphi exercises (e.g., [,,,]).

After the selection, the facilitator contacted the experts via e-mail. That first contact included an introduction to the aims of this work and the Delphi method.

The invitation also included the estimated time taken to answer the online questionnaires and how often the researchers would contact them. Finally, we offered a meeting to clarify any questions or doubts concerning the goals and methods used. Once the experts confirmed their interest in participating, an e-mail containing the link to the questionnaire was sent. In addition, the facilitator sent reminders prior to the questionnaires’ deadlines.

3.2.2. Profile of Members of the Panel of Experts

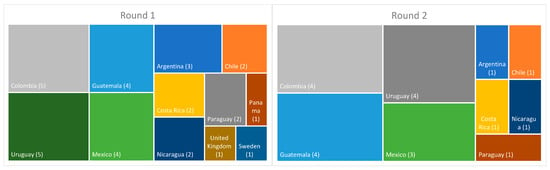

The researchers aimed to assemble a heterogeneous panel of Latin American experts to collect governmental, non-governmental, and academic perspectives. Table 1 and Figure 3 confirm that that objective was achieved. The majority of the experts resided in Colombia, Guatemala, Uruguay, and Mexico.

Table 1.

Adaptation experts’ profiles.

Figure 3.

Adaptation experts’ country of residence.

Table 1 provides an overview of the experts’ gender, years of experience, type of organization where the experts acquired most of their experience in adaptation, current professional role, and professional background. In terms of gender, the participation of women and men was balanced in the two rounds. A significant number of the experts had long-standing (>10 years) adaptation-related professional experience (69% and 75% for the first and second rounds, respectively). In terms of the type of institution/organization in which they had spent most of their adaptation-related career, the results were also well distributed between government (G), academia/research (A/R), development aid (D) organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). In terms of their current role, most experts identified themselves as researchers (38% and 45% in each round), followed by policymakers (25%, 15%) and consultants (22%, 20%). In addition, the experts identified other professional roles (19%, 20%), such as director, manager, independent consultant, specialist, and professor. Most experts had backgrounds in environmental or natural sciences (41%, 50%), followed by social sciences (37%, 30%) and applied sciences (16%, 20%). Only 6% of the experts included in the first round indicated that they had a background in environmental and social sciences.

3.2.3. Questionnaires

In this exercise, we performed two rounds of online questionnaires. We developed and shared the online questionnaires using Survey Hero (https://www.surveyhero.com/). Together with sharing and collecting the information, the tool calculated the arithmetic average, mean and standard deviation, and weighting (where appropriate).

Following the Delphi method (Section 3.1), the first questionnaire primarily consisted of open-ended questions to allow experts to have freedom in their responses and allow us to obtain individual perspectives, which should be the basis of the following questionnaire. The second questionnaire was mainly made up of closed questions.

To obtain information on both definitions being studied and provide guidance on the aspects that could be improved, the questionnaires included information about the study’s aim, a summary of the Delphi method, and additional background information. The questions were organized into three main sections: (A) adaptation definition, (B) successful adaptation definition, and (C) elements for operationalizing the definition of successful adaptation. Sections A and B included questions on the overall level of agreement, the elements of the definitions under study that the experts agreed and disagreed with, and additional elements that could be considered to improve the definitions. We also included a question on the need for definitions specific to each management level. Section C included questions on the operationalization of the definition of successful adaptation. Here, the experts could identify useful and missing elements in the definition that could support the evaluation of adaptation at different management levels. Finally, the first questionnaire included an additional section (D) relating to the experts’ background information.

The second questionnaire was prepared based on the answers to the first questionnaire [,]. First, we analyzed the answers (including the frequencies, means and standard deviations, where appropriate). Afterwards, we grouped similar items. In this case, we listed all the elements identified by the experts in each question. Based on that, the experts confirmed their agreement or disagreement with the listed elements. Additionally, they identified the degree of importance for improving the definitions or the usefulness of those elements. Experts could identify more than one aspect that they agreed or disagreed with. Furthermore, each section had an additional field where the experts could share further comments.

In both questionnaires, Likert-type scale questions were included to identify and verify their level of agreement with both definitions (total disagreement to total agreement). The average agreement included a scale of 3 (−/+). We calculated the level of consensus considering the answers given as “agree and totally agree” scales (scales 4 and 5). To avoid misunderstandings, in this work the percentage symbol (%) included in the results refers to the number of experts answering a question or indicating their agreement/disagreement. Weights on importance or usefulness are reported as a fraction of 1 (0 not important or not useful/1 very important or very useful). The weights included in this work represent the average weight for each element, as indicated by the experts.

In terms of time, the experts had at least one month to answer and complete the questionnaires. After the analysis, we prepared and shared a report presenting the answers and arguments for each questionnaire round. The questionnaires were developed in Spanish and implemented between September 2020 and March 2021.

3.2.4. Qualitative Analysis

We based our analysis on the information provided by the experts in the first questionnaire. In addition, we developed a category system using inductive category formation (categories based on the data) [], which allowed us to identify the elements of the definitions under analysis with which the experts agreed or disagreed. We also used this approach to identify elements proposed to improve the definitions.

Once the category system was developed, we extracted and analyzed information about the frequency of the different elements. That information served as the basis with which to develop the list of elements provided in the second questionnaire, in which the experts could identify their agreement or disagreement.

The researchers used the MAXQDA software to qualitatively analyze the answers given in the open-ended questions in the first questionnaire.

3.2.5. Consensus with the Definitions

The Delphi exercises stop once a predetermined level of consensus is reached. To define the experts’ level of consensus with the definitions under study, we followed the limit used by Doria et al. [] (>80%).

Therefore, this exercise stopped after the second questionnaire, as the level of agreement with the definition of adaptation reached 85%. However, as we were not proposing a new definition of successful adaptation, we also decided to stop the exercise with an agreement level of only 50%. While the level of agreement with the definition of successful adaptation was lower than the >80% defined by Doria et al. [], the authors considered it a stable response (compared to the 53% obtained in the first questionnaire). Stable responses could be a “more reliable indicator of consensus” [] (p. 1011). This low level of agreement reflects the experts’ different concerns about this definition.

4. Results

Below, we present the main results related to the revision of the definitions of adaptation together with those of successful adaptation. In a separate section, we present the results relating to the aggregation of information. Appendix A presents a summary of the results.

4.1. Perspectives on the Definitions

In this section, we present the results related to the level of agreement or consensus, the elements upon which the experts agreed, and those upon which they disagreed. Additionally, we list the elements identified by the experts which could be considered in future revisions of the definitions.

4.1.1. Consensus with the Definitions

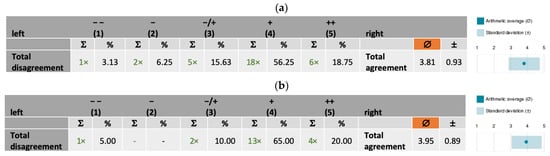

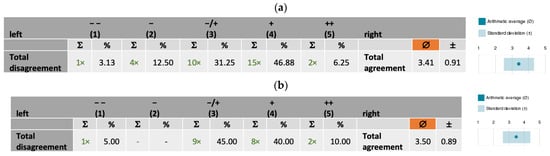

We consulted with the experts regarding their level of agreement with the IPCC’s [] definition of adaptation. In both rounds, the level of agreement with the IPCC’s definition was high (75% and 85% of the answers, respectively). Therefore, there was consensus among the experts (>80%) regarding this definition. The average agreement levels were 76% and 79% (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Agreement with the IPCC’s [] definition of climate adaptation: (a) first round, (b) second round (source: SurveyHero).

General comments on the definition of climate adaptation mentioned its complexity, which depends on different factors such as level of implementation, sector, and type of adaptation. Comments also highlighted that more than specific definitions, work on adaptation needs to be guided by general principles or criteria, allowing the alignment of actions with specific objectives.

Similarly, as for the definition of adaptation, experts identified their level of agreement with the definition of successful adaptation proposed by Doria et al. []. The experts agreed less with the definition of successful adaptation than with the presented definition of adaptation. After the two rounds, no consensus was reached. The levels of agreement were 53% and 50%. The average levels of agreement were 68% and 70% for each round, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Agreement with Doria et al.’s [] definition of successful climate adaptation: (a) first round, (b) second round (source: SurveyHero).

Regarding the need to have specific definitions for each management level, 69% of the experts did not identify such a need related to the definition of adaptation. In the case of the definition of successful adaptation, in the first questionnaire 56% of the experts identified that having a specific definition for each level of management could be useful. Therefore, the question was reframed in the second questionnaire. We asked the experts to identify their preference for these two options: (1) specific definitions for each management level, and (2) a general definition adaptable to each level of management. As a result, 90% of the experts chose option 2.

4.1.2. Elements of Agreement with the Definitions

In the first round, the experts were asked to identify the elements of the definitions with which they agreed. Regarding the adaptation definition, there were two aspects with which the experts agreed more: adaptation as a process of adjustment (56%) and the inclusion of human systems (56%). These were followed by the indirect reference to variability and climate change (34%) and human intervention in natural systems (34%). On the other hand, only 13% agreed with the reference to both systems (natural and human), and 6% agreed with the differentiation among both systems.

Some of the elements listed above were listed separately in the second round (e.g., variability and climate change). Experts were asked to confirm their agreement with and identify the importance of each element. More than 75% of the experts agreed with all the listed elements. Regarding importance, the reference to both systems in the definition scored the highest (0.91). The element about which all experts (100%) agreed was the reference to “exploit beneficial opportunities”, while it achieved the lowest weight in terms of importance (0.68).

Regarding the definition of successful adaptation, the experts agreed on reducing risks and vulnerability (44%) as well as sustainability (31%) in the first round. In addition, other aspects were mentioned, such as adjustment (16%), predetermined level (13%), and a focus on climate change (6%).

In the second round, the experts confirmed their agreement with those elements and identified their importance. The experts agreed with most of the elements (>80%). Only the reference to a predetermined level obtained less than 80% agreement (55%). Most experts agreed (95%) with the reference to reducing risks. However, the experts identified reducing vulnerability as the most important element (0.96).

4.1.3. Elements of Disagreement with the Definitions

Despite the high level of agreement with the definition of adaptation, 41% of the experts identified elements of it with which they disagreed. The aspects identified in the first round were the differentiation of both systems (41%), adaptation as an adjustment process (22%), and the limitation to climate change (3%). Except for the limitation to climate change, the experts agreed with all the elements identified as elements of the agreement in the first round. Therefore, we asked the experts to confirm their agreement or disagreement with the elements in the second round. As a result, the only element most of the experts disagreed with was the limitations to climate change (50%).

For successful adaptation, many of the aspects where experts showed agreement in the first round were also identified as elements of disagreement: sustainability (31%), predetermined level (28%), adjustment (15%), measurement elements (9%), scope (9%), and the focus on climate change (6%). In the second round, the experts confirmed whether they agreed or disagreed with the listed elements. In this case, the experts disagreed with two elements: a lack of elements that allowed measuring progress (75%) and the reductionist approach (related to disaster risk reduction, not considering the transformative character of adaptation) (40%).

4.1.4. Proposed Elements

In the first round, the experts identified elements which in their view were missing in the IPCC’s [] definition of adaptation; among these were components of the global goal on adaptation (34%), scope (22%), systemic approach (19%), and type of adaptation (16%). In addition, the experts also mentioned the definition of adjustment (9%), global change (9%), sustainability (6%), temporality (6%), and maladaptation (6%).

In the second round, the experts indicated which elements they agreed with and identified their importance to improve the definitions. The four elements with which the experts agreed the most (>80%) were the increase in adaptive capacity (90%), reduction in vulnerability (90%), systemic approach (85%), and temporality (80%). The reference to reducing vulnerability ranked the highest in terms of importance (0.94).

The experts also identified elements that could be part of a future revision of the definition of successful adaptation. The elements identified in the first questionnaire were the components of the global goal on adaptation (38%), sustainability (25%), scales (19%), type of adaptation (19%), elements of measuring and monitoring (19%), scope (16%), climate variability (9%), stakeholders (9%), predetermined level (6%), and other elements (16%).

In the second round, the experts identified their agreement with and the importance of the listed elements. As a result, more of the elements received a high level of agreement among the experts (>70%). Increasing resilience garnered the most agreement (100%). In terms of importance, the increase in adaptive capacity scored the highest (0.93).

4.2. Operationalization of the Definition of Successful Adaptation

Despite the efforts made, the academic literature states that the existing definitions are not operational. That is, at present the definitions do not support efforts to evaluate progress made through climate change adaptation measures implemented at different management levels [,,,].

In this section, we present the results related to the usefulness of Doria et al.’s definition [] for measuring progress in climate adaptation. Additionally, we present methods and approaches that could facilitate the aggregation of information on progress. To this end, we introduce a list of the criteria and indicators identified by the experts which could improve capacities to measure progress at different levels of management.

4.2.1. Usefulness of the Definition of Successful Adaptation at Different Management Levels

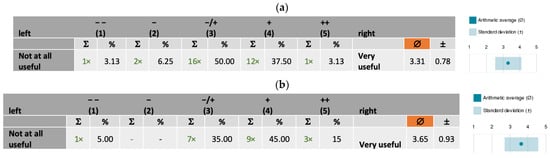

We asked the experts to identify how useful the definition of successful adaptation is, in general, for supporting the evaluation of climate change adaptation (Figure 6). In total, 41% and 60% of the experts found the definition useful, in each of the rounds.

Figure 6.

Successful adaptation definition general usefulness: (a) first round, (b) second round.

When asked about the usefulness at the different management levels (local, subnational, national, and global), the experts stated that the definition was progressively more useful when moving from the local to higher management levels (31%, 44%, 66%, and 75%, respectively) (Figure 7). However, at the local level only, some experts (13%) stated that the definition was not useful, and 9% identified it as not applicable.

Figure 7.

Usefulness of the successful adaptation definition at different management levels (first round).

In the second round, the definition was identified as useful for the local and subnational levels by 80% of the experts and for the national and global levels by 85%. This time, the experts also identified the degree of usefulness of the definition for each level. The experts identified the definition as less useful at the local level (0.65) compared to the national level (0.76). The experts gave the same weight (0.73) for the subnational and global levels (Table 2). In this case, the difference for the different levels was smaller than the one identified in the first round.

Table 2.

Usefulness of the definition of successful adaptation at different management levels (second round).

After identifying the general usefulness of the definition of successful adaptation, the experts identified useful and missing elements for different levels of management. Table 3 shows that the experts identified the same elements for the different levels with slight differences in the agreement and usefulness (weight).

Table 3.

Useful elements of the successful adaptation definition.

On the contrary, there were differences when comparing the elements identified as missing from the definition (Table 4). The experts identified three elements to be missing for the different levels of management: adaptive capacity, resilience, and measuring elements. In comparison, the definition of the scope, climate variability, levels of management, and cultural aspects were identified as missing only for the local level. In addition, the elements of context and the definition of adjustment were identified as missing only for the subnational to global levels.

Table 4.

Elements missing from the successful adaptation definition.

4.2.2. Aggregation

Another component of the exercise was investigating aspects of the feasibility of aggregating information on adaptation. In this case, we refer to information from the local level that can inform progress made at the national level, which at the same time could serve to inform global progress made in adaptation, as suggested by Magnan [].

In the first questionnaire, the experts identified elements used to measure progress at the local level that should be considered at the global level. As a result, 66% of the experts indicated criteria or indicators, 19% mentioned methods of measuring progress, and 9% referred to approaches. Table 5 shows the methods and approaches indicated by the experts. Section 4.2.3 includes more detail on the identified criteria and indicators.

Table 5.

Identified methods and approaches.

Additionally, 28% of the experts questioned the overall feasibility of aggregating information on adaptation. Considering the results obtained from the first questionnaire, we asked the experts specifically about the feasibility of aggregating information on adaptation progress from the local to the global level in the second round. As a result, only 35% agreed on the feasibility, while 15% thought that it was not possible to aggregate information. A total of 50% of the experts were unsure.

4.2.3. Criteria and Indicators for Each Level of Management

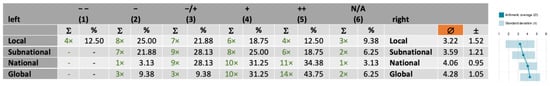

As mentioned before, in the first questionnaire 66% of experts identified criteria or indicators that would support adaptation monitoring and evaluation efforts at different management levels, which would, at the same time, facilitate the aggregation of information progress on adaptation. We grouped the criteria and indicators identified in the previous round into the three components of the global goal on adaptation, i.e., increasing adaptive capacity, increasing resilience, and reducing vulnerability. The information was presented for each level: local, subnational, national, and global. The experts identified whether the criteria and indicators were useful for that specific management level and their degree of usefulness (Table 6).

Table 6.

Identified criteria and indicators for the different for management levels.

Besides the elements listed in Table 6, in the second round, some experts identified additional elements for each component of the GGA. These results might indicate that additional elements could have been identified if additional rounds were performed.

5. Discussion

This section presents our reflections on the results obtained from a panel of Latin American experts regarding the revisions of the definitions of climate adaptation [] and successful adaptation []. We present the level of agreement with the definitions and the elements that could help in evaluation and aggregation efforts. Additionally, we reflect on the Delphi method and its limitations for the co-production of knowledge in climate change adaptation research.

5.1. Revision of the Definitions

This exercise did not aim to produce new definitions but rather to revise and identify different elements and issues related to the definitions under study. Below, we present our reflections based on the issues identified by the panel of experts.

5.1.1. Adaptation Definition

We identified a consensus among the experts regarding the IPCC’s [] definition of adaptation. The element upon which most experts agreed was the reference to “exploit beneficial opportunities”. Nevertheless, that reference scored the lowest in terms of importance. This result could reflect the concerns expressed by some experts regarding a “positive” view of the effects of climate change. According to some of the comments, the definition should focus on the adverse effects of climate change.

Opinions were divided (50%) about the focus on climate change as an element of disagreement after the two questionnaire rounds. For example, some experts proposed including general aspects of global change (i.e., environmental degradation). This result could reflect the debate of identifying (or not identifying) adaptation as a separate issue from the development agenda [,].

Among the elements proposed by the experts, the ones identified as more important were those related to the components of the global goal on adaptation (GGA). This is relevant as it confirms the importance of evaluating progress in the three components of the GGA, which is an issue covered in the current preparation work ahead of the first global stocktake.

5.1.2. Successful Adaptation Definition

In the case of Doria et al.’s [] definition of successful adaptation, most experts agreed with the reference to a reduction in risks (95%). However, the experts identified the reduction in vulnerability as the most important element. This last aspect is aligned with research that highlights the fact that reducing vulnerability should be one of the objectives of adaptation (e.g., [,]). On the other hand, the experts disagreed with the lack of elements to allow for measurement (75%).

Regarding the elements used to improve the definition, most experts agreed on increasing resilience (100%) and increasing adaptive capacity (95%). The experts identified adaptive capacity as the most important element, in line with Ford and Berrang-Ford [] and Dilling et al. [].

Regarding the general usefulness of the definition for evaluation purposes, 60% of the experts identified the definition as useful. Additionally, most of the experts (90%) agreed that there was no need for a specific definition for each management level. Instead, the experts identified a general definition adaptable to each management level as the best alternative. This general definition could be supported by criteria and indicators applicable to each level. The results presented in Table 6 are an example of how the criteria and indicators might vary depending on the level of implementation of adaptation measures.

Additionally, according to the experts, the definition of successful adaptation has a lower degree of usefulness at the local level than when compared to higher management levels. While there are some critics of the view of adaptation as only a local concern (e.g., []), the results of this research confirm that it is necessary to consider the local context and its complexities when developing criteria and indicators for the evaluation of climate adaptation. Moreover, care is needed regarding the framing used to define how successful or effective an adaptation measure is []. Finally, any effort related to evaluating adaptation needs first to showcase the characteristics of the level where adaptation is implemented.

5.2. Aggregation

Contrary to mitigation, it is difficult to aggregate information on the progress on adaptation []. However, the global stocktake of the Paris Agreement’s aim of assessing collective progress [] demands that academia, practitioners, and policy-makers find ways to present information on adaptation progress.

This exercise reflects how challenging the effort to aggregate information on adaptation can be, with only 35% of the experts thinking it to be feasible. Nevertheless, the experts identified three approaches—objective measures, expert judgment, and inductive methods—that need to be considered when evaluating adaptation. In this regard, as shown in Table 5, most of the experts considered objective measures as the preferred and most useful ones. However, at the same time, the experts mentioned the challenges of measuring or establishing adaptation indicators in different sections of the questionnaires. This might imply that a combination of approaches should be used when evaluating progress made on adaptation. This is consistent with different research that suggests the use of different approaches (i.e., []).

At the same time, and as a more detailed contribution than the criteria identified by Doria et al. [], it was possible to investigate different criteria and indicators at the different levels of management that could support efforts to aggregate information to inform global processes, such as the global stocktake. Experts identified the usefulness of the proposed criteria and indicators at each management level.

5.3. Added Value of the Delphi Method for Co-Production of Climate Change Adaptation Knowledge

This exercise has proven the Delphi method to be helpful for the co-production of knowledge related to adaptation to climate change. It allowed us to investigate, in an interactive way, the views on the definitions of adaptation and successful adaptation from the IPCC [] and Doria et al. [], respectively.

As a field related to different sectors and levels of governance, efforts related to climate adaptation require processes and methods that allow for exchange and inclusion among a diverse group of stakeholders. In this case, the use of the Delphi method fulfills many characteristics of co-production: as a means of addressing complex problems, producing knowledge, and recognizing different perspectives, while also allowing collaboration among various actors. The feedback process can be considered a social learning process []. Moreover, in this exercise, the Delphi method facilitated collecting information and identifying different perspectives from a heterogeneous group of experts with different backgrounds, with different levels of technical expertise, and from different countries, despite the ongoing pandemic.

The information obtained can facilitate a common understanding of the goals and results achieved from adaptation actions. Furthermore, the method proved to be flexible, a valuable characteristic for adaptation research, considering the different contexts in which adaptation measures are designed and implemented.

Although the results obtained are not a statistical representation, they present the view of experts in the field, reflecting on critical aspects that need to be considered when evaluating adaptation. Moreover, in this case, the information reflects a regional perspective.

As a limitation of this study, it should be mentioned that only the survey coordinator performed the coding and analysis of the responses. This could have led to biases in the list of elements or issues identified. Sufficient time needed to be allocated for the coding phase, especially after the first round of questionnaires, which mainly consisted of open-ended questions. Following an inductive analysis, the coding phase was the most time-consuming part of the exercise. Furthermore, there were challenges related to the possibility of different interpretations of the questions and the different nature of the issues identified by each expert during the development of the exercise [,].

6. Conclusions

Global policy agendas might guide adaptation actions, but actions are implemented at the local level. Adaptation implementation and success depend on site-specific conditions. Therefore, before adaptation progress or success can be evaluated more consistently on such different levels, we need to know how climate adaptation is defined and what is considered progress and success. Additionally, there is a need to identify ways to support efforts to aggregate information on adaptation progress. However, this discussion is absent from the climate-related literature on Latin America. Therefore, we investigated the perspectives of Latin American experts on the aforementioned issues using the Delphi method. Our results confirm the complexity of the discourse on adaptation.

Overall, the Delphi method proved to be useful for the co-production of knowledge, facilitating the identification of different aspects that can serve as a basis for improving climate change adaptation monitoring and evaluation activities.

We found a consensus (>80%) with the IPCC’s definition of climate adaptation [] among the Latin American experts. In contrast, there was no consensus regarding the definition of successful adaptation developed by Doria et al. []. The aspects with which most of the experts disagreed were the lack of elements to support evaluation efforts and the lack of recognition of the potential for transformation that adaptation can provide. Instead, the experts identified resilience and adaptive capacity as elements that could improve Doria et al.’s [] definition of successful adaptation.

Additionally, we presented a list of criteria and indicators of successful adaptation that could support evaluation and aggregation efforts. Such indicators have been identified as a knowledge gap in the Latin American region. Here, we observed that most of the criteria and indicators proposed by the experts were related to adaptive capacity, identified in the climate-related literature as a crucial component when implementing adaptation measures. Our results confirm that there is no one method or one approach for evaluating adaptation.

The criteria and indicators identified in this exercise can help in the investigation of successful adaptation characteristics applicable at different management levels while providing guidance for policy makers and practitioners ahead of the first global stocktake. While our results are limited to the identification of criteria and indicators, they could specifically contribute to a structured approach that captures aspects of representativeness and comparability, as suggested by Magnan and Ribera []. For example, regarding the criteria and indicators identified for the adaptive capacity component of the GST, the elements of context and the factors that influence the performance of the adaptation measures could be investigated.

Additionally, future research efforts should focus on developing and characterizing the identified criteria and indicators for the different levels of management by identifying the kind of information needed at each level, how the information should be collected, and how it could be aggregated and integrated into the reporting tools. The Delphi method could also be applied to these objectives. Similar exercises could also be developed in other regions to identify, compare and analyze how the different perspectives, elements, criteria, and indicators identified depend on the geographical context.

In conclusion, we present the level of agreement of experts and ways to improve the definitions of climate adaptation and successful climate adaptation, as well as criteria and indicators that could help to aggregate adaptation information from the local to the global level. The outcomes, which present a regional perspective, can guide the Paris Agreement’s global stocktake and contribute to the debate on successful climate adaptation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G.B.; methodology, T.G.B.; formal analysis, T.G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G.B.; writing—review and editing, T.G.B., J.S. and M.M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. This research was funded by the Climate Service Center Germany (GERICS), Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This paper does not present medical research. Participation in the research was voluntary. The framing and settings were non-coercive. The nature of the collected information posed no harm to participants. The collected information was treated confidentially, and data are available, if requested, only in anonymized form.

Informed Consent Statement

The questionnaires followed the principle of prior informed consent: all participants were informed about the research’s background, method, and aim. Additionally, written informed consent was obtained from the experts included in the first questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

The original material of this investigation is in Spanish. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available to guarantee the participants’ anonymity.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Latin American experts who participated in the first and second round of the Delphi method exercise: A. Aguilar, X. Apestegui, F. Aragón-Durand, A.C. Borda, R. Bórquez, M. Caffera, N. Canales, E. Castellanos, A. Cid Salinas, J. Cordano, I. Delgado-Pitti, P. Devis, L. Di Pietro, M. Florian, G. Fuentes Braeuner, H. Garate, A. García González, P.M. García Meneses, M. Jadrijevic, C. Jones, O. Jordan, I. Lorenzo, A. Martín, F. Menna, G.J. Nagy, L.A. Ortega Fernández, N.C. Páez Ortiz, A. Rodríguez Osuna, D. Ryan, J.O. Samayoa Juárez, R. Scribano, and A. Sobenes. We also would like to thank E. Gómez, S. Muwafu, and G. Langendijk for their valuable comments, which helped to improve the manuscript. This research contributes to the climate cluster of excellence CLICCS funded by DFG.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1 presents the summary of the results obtained after the second round of the Delphi panel regarding the most important elements of the definitions of adaptation [] (consensus > 80%) and successful adaptation [].

Table A1.

Summary of findings.

Table A1.

Summary of findings.

| Adaptation Definition (IPCC []) | |

|---|---|

| Agreement with definition | 85% |

| Elements of agreement |

|

| Elements of disagreement |

|

| Proposed elements |

|

| Successful adaptation definition (Doria et al. []) | |

| Agreement with definition | 50% |

| Elements of agreement |

|

| Elements of disagreement |

|

| Proposed elements |

|

References

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jacob, D.; Taylor, M.; Guillén Bolaños, T.; Bindi, M.; Brown, S.; Camilloni, I.A.; Diedhiou, A.; Djalante, R.; Ebi, K.; et al. The Human Imperative of Stabilizing Global Climate Change at 1.5 °C. Science 2019, 365, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Adaptation Gap Report 2020; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; ISBN 9789280738346. [Google Scholar]

- de Coninck, H.; Revi, A.; Babiker, M.; Bertoldi, P.; Buckeridge, M.; Cartwright, A.; Dong, W.; Ford, J.; Fuss, S.; Hourcade, J.-C.; et al. Strengthening and Implementing the Global Response. In Strengthening and Implementing the Global Response. In: Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P.R., Pirani, A., Moufouma-Okia, W., Péan, C., Pidcock, R., et al., Eds.; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 313–443. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N.; Arnell, N.W.; Tompkins, E.L. Successful Adaptation to Climate Change across Scales. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2005, 15, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, M.; Reckien, D.; Viner, D.; Adler, C.; Cheong, S.-M.; Conde, C.; Constable, A.; de Perez, E.C.; Lammel, A.; Mechler, R.; et al. Decision Making Options for Managing Risk. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Berrang-Ford, L.; Pearce, T.; Ford, J.D. Systematic Review Approaches for Climate Change Adaptation Research. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AC. Report on the Workshop on the Monitoring and Evaluation of Adaptation; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, S.C.; Boykoff, M.T. (Eds.) Successful Adaptation to Climate Change: Linking Science and Policy in a Rapidly Changing World, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780415525008. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter, T. Linking Monitoring and Evaluation of Adaptation to Climate Change across Scales: Avenues and Practical Approaches. In Monitoring and Evaluation of Climate Change Adaptation: A Review of the Landscape; New Directions for Evaluation; Bours, D., McGinn, C., Pringle, P., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, J.; O’Neill, S.; Waller, S.; Rogers, S. Reducing the Risk of Maladaptation in Response to Sea-Level Rise and Urban Water Scarcity. In Successful Adaptation to Climate Change: Linking Science and Policy in a Rapidly Changing World; Moser, S.C., Boycoff, M.T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Engle, N.L.; de Bremond, A.; Malone, E.L.; Moss, R.H. Towards a Resilience Indicator Framework for Making Climate-Change Adaptation Decisions. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2014, 19, 1295–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janetos, A.C. Why Is Climate Adaptation so Important? What Are the Needs for Additional Research? Clim. Chang. 2020, 161, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, L.; Prakash, A.; Zommers, Z.; Ahmad, F.; Singh, N.; de Wit, S.; Nalau, J.; Daly, M.; Bowman, K. Is Adaptation Success a Flawed Concept? Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaque, A.; Eakin, H.; Vij, S.; Chhetri, N.; Ramhan, F.; Huq, S. Multilevel Governance in Climate Change Adaptation: Conceptual Clarification and Future Outlook. Reg. Env. Chang. 2021, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Annex II: Glossary. In Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Mach, K.J., Planton, S., von Stechow, C., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Doria, M.d.F.; Boyd, E.; Tompkins, E.L.; Adger, W.N. Using Expert Elicitation to Define Successful Adaptation to Climate Change. Environ. Sci. Policy 2009, 12, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Arnell, N.W.; Tompkins, E.L. Adapting to Climate Change: Perspectives across Scales. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2005, 15, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, L.; Martínez, G.; Naswa, P. Adaptation Metrics: Perspectives on Measuring, Aggregating and Comparing Adaptation Results; Christiansen, L., Martinez, G., Naswa, P., Eds.; UNEP DTU Partnership: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; ISBN 9788793458277. [Google Scholar]

- Berrang-Ford, L.; Biesbroek, R.; Ford, J.D.; Lesnikowski, A.; Tanabe, A.; Wang, F.M.; Chen, C.; Hsu, A.; Hellmann, J.J.; Pringle, P.; et al. Tracking Global Climate Change Adaptation among Governments. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olazabal, M.; De Gopegui, M.R.; Tompkins, E.L.; Venner, K.; Smith, R. A Cross-Scale Worldwide Analysis of Coastal Adaptation Planning. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klein, R.J.T.; Adams, K.M.; Dzebo, A.; Davis, M.; Siebert, C.K. Advancing Climate Adaptation Practices and Solutions: Emerging Research Priorities; Stockholm Environment Instittue: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.R.; Adger, W.N.; Brown, K. Adaptation to Environmental Change: Contributions of a Resilience Framework. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2007, 32, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nalau, J.; Verrall, B. Mapping the Evolution and Current Trends in Climate Change Adaptation Science. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, E.; Lemos, M.F.; Astigarraga, L.; Chacón, N.; Cuvi, N.; Huggel, C.; Miranda, L.; Moncassim Vale, M.; Ometto, J.P.; Peri, P.L.; et al. Central and South America. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, I.; Huggel, C.; Ramajo, L.; Chacón, N.; Ometto, J.P.; Postigo, J.C.; Castellanos, E.J. Climate Change-Related Risks and Adaptation Potential in Central and South America during the 21st Century. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 033002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows: Summary and Recommendations by the Standing Committee on Finance on the 2018 Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2018; Volume 121. [Google Scholar]

- Schalatek, L.; Watson, C. The Green Climate Fund (GCF); Heinrich Böll Stiftung, ODI: Washington, DC, USA; London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, D.; Bustos, E. Knowledge Gaps and Climate Adaptation Policy: A Comparative Analysis of Six Latin American Countries. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 1297–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Iyer, S.; New, M.G.; Few, R.; Kuchimanchi, B.; Segnon, A.C. Daniel Morchain Interrogating ‘Effectiveness’ in Climate Change Adaptation: 11 Guiding Principles for Adaptation Research and Practice. Clim. Dev. 2021, 13, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Adams, H.; Adelekan, I.; Adler, C.; Adrian, R.; Aldunce, P.; Ali, E.; Begum, R.A.; Bednar-Friedl, B.; et al. Technical Summary. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- UNFCCC. Decision 1/CP.21 Adoption of the Paris Agreement; UNFCCC: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S.; McKenna, H. Research Guidelines for the Delphi Survey Technique. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirschhorn, F.; Veeneman, W.; van de Velde, D. Inventory and Rating of Performance Indicators and Organisational Features in Metropolitan Public Transport: A Worldwide Delphi Survey. Res. Transp. Econ. 2018, 69, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montijo-Galindo, A.; Ruiz-Luna, A.; Betancourt Lozano, M.; Hernández-Guzmán, R. A Multicriteria Assessment of Vulnerability to Extreme Rainfall Events on the Pacific Coast of Mexico. Coast. Manag. 2020, 48, 623–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, A.; Ardalan, A.; Takian, A.; Ostadtaghizadeh, A.; Naddafi, K.; Bavani, A.M. Health System Plan for Implementation of Paris Agreement on Climate Change (COP 21): A Qualitative Study in Iran. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, A.; Farani, A.Y.; Karimi, S.; Azadi, H.; Nadiri, H.; Scheffran, J. Identifying Sustainable Rural Entrepreneurship Indicators in the Iranian Context. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.H.; Mahbubul, M.A. Developing a Conceptual Model for Identifying Determinants of Climate Change Adaptation. J. Clim. Chang. 2021, 7, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, T.J.; Fogelman, C. Déjà vu or Something New? The Adaptation Concept in the Climate Change Literature. Geoforum 2013, 48, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; McDowell, G.; Jones, J. The State of Climate Change Adaptation in the Arctic. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eriksen, S.H.; Nightingale, A.J.; Eakin, H. Reframing Adaptation: The Political Nature of Climate Change Adaptation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 35, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, B.; Henstra, D. Studying Local Climate Adaptation: A Heuristic Research Framework for Comparative Policy Analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 31, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sietsma, A.J.; Ford, J.D.; Callaghan, M.W.; Minx, J.C. Progress in Climate Change Adaptation Research. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Berrang-Ford, L. The 4Cs of Adaptation Tracking: Consistency, Comparability, Comprehensiveness, Coherency. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2016, 21, 839–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magnan, A.K.; Ribera, T. Global Adaptation after Paris. Science 2016, 352, 1280–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, L.; Daly, M.E.; Travis, W.R.; Wilhelmi, O.V.; Klein, R.A. The Dynamics of Vulnerability: Why Adapting to Climate Variability Will Not Always Prepare Us for Climate Change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2015, 6, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, S.; Berman, R.; Dixon, J.; Lebel, S. Time for a Systematic Review: A Response to Bassett and Fogelman’s “Déjà vu or Something New? The Adaptation Concept in the Climate Change Literature”. Geoforum 2014, 51, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Owen, G. What Makes Climate Change Adaptation Effective? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 62, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AC-UNFCCC. Approaches to Reviewing the Overall Progress Made in Achieving the Global Goal on Adaptation; Technical Paper; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, E.L.F. Maladaptation: When Adaptation to Climate Change Goes Very Wrong. One Earth 2020, 3, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, Å. Global Adaptation Governance: An Emerging but Contested Domain. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2019, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNFCCC. Monitoring and Assessing Progress, Effectiveness and Gaps under the Process to Formulate and Implement National Adaptation Plans: The PEG M&E Tool. 2015. Available online: https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/NAPC/Documents%20NAP/UNFCCC_PEGMonitoring_Tool.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- GEF-STAP. Strengthening Monitoring and Evaluation of Climate Change Adaptation; Global Environmental Facility: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fiala, N.; Puri, J.; Mwandri, P. Becoming Bigger, Better, Smarter: A Summary of the Evaluability of Green Climate Fund Proposals; Green Climate Fund Independent Evaluation Unit: Songdo, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. The Adaptation Gap Report: Towards Global Assessment; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, E.L.F.; Tanner, T.; Dube, O.P.; Adams, K.M.; Huq, S. The Debate: Is Global Development Adapting to Climate Change? World Dev. Perspect. 2020, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnan, A.K. Metrics Needed to Track Adaptation. Nature 2016, 530, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leiter, T.; Olhoff, A.; Al Azar, R.; Barmby, V.; Bours, D.; Wei, V.; Clement, C.; Bank, W.; Dale, T.W.; Davies, C.; et al. Adaptation Metrics Current Landscape and Evolving Practices; UNEP DTU Partnership: Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter, T. Do Governments Track the Implementation of National Climate Change Adaptation Plans? An Evidence-Based Global Stocktake of Monitoring and Evaluation Systems. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 125, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Ellis, J. Communicating Progress in National and Global Adaptation to Climate Change; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Craft, B.; Fisher, S. Measuring the Adaptation Goal in the Global Stocktake of the Paris Agreement. Clim. Policy 2018, 18, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, E.L.; Vincent, K.; Nicholls, R.J.; Suckall, N. Documenting the State of Adaptation for the Global Stocktake of the Paris Agreement. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2018, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magnan, A.K.; Chalastani, V.I. Towards a Global Adaptation Progress Tracker: First Thoughts; IDDRI: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Atteridge, A.; Remling, E. Is Adaptation Reducing Vulnerability or Redistributing It? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2018, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, T. The Adaptation M&E Navigator: A Decision Support Tool for the Selection of Suitable Approaches to Monitor and Evaluate Adaptation to Climate Change. In Evaluating Climate Change Action for Sustainable Development; Uitto, J.I., Puri, J., van den Berg, R.D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- UNFCCC. Progress, Experience, Best Practices, Lessons Learned, Gaps, Needs and Support Provided in the Process to Formulate and Implement National Adaptation Plans; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.D.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Lesnikowski, A.; Barrera, M.; Jody Heymann, S. How to Track Adaptation to Climate Change: A Typology of Approaches for National-Level Application. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, C.; Shaker, R.R.; Das, R. A Review of Approaches for Monitoring and Evaluation of Urban Climate Resilience Initiatives. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta, J. Current Validity of the Delphi Method in Social Sciences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2006, 73, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguant-Álvarez, M.; Torrado-Fonseca, M. El Método Delphi. REIRE. Rev. d’Innovació I Recer. Educ. 2016, 9, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirschhorn, F. Reflections on the Application of the Delphi Method: Lessons from a Case in Public Transport Research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2019, 22, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, J.A.G.M. Delphi Questionnaires Group Interviews A Comparison Case. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1990, 37, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, K.; Daly, M.; Scannell, C.; Leathes, B. What Can Climate Services Learn from Theory and Practice of Co-Production? Clim. Serv. 2018, 12, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, S.; Hasson, F.; McKenna, H.P. A Critical Review of the Delphi Technique as a Research Methodology for Nursing. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2001, 38, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.G. Use (and Abuse) of Expert Elicitation in Support of Decision Making for Public Policy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7176–7184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D.; Chan, A.W. Developing a Guideline for Clinical Trial Protocol Content: Delphi Consensus Survey. Trials 2012, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kuckartz, U.; Rädiker, S. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA. Text, Audio, and Video; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 9783030156701. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).