Enhancing the Prospect of Corporate Sustainability via Brand Equity: A Stakeholder Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

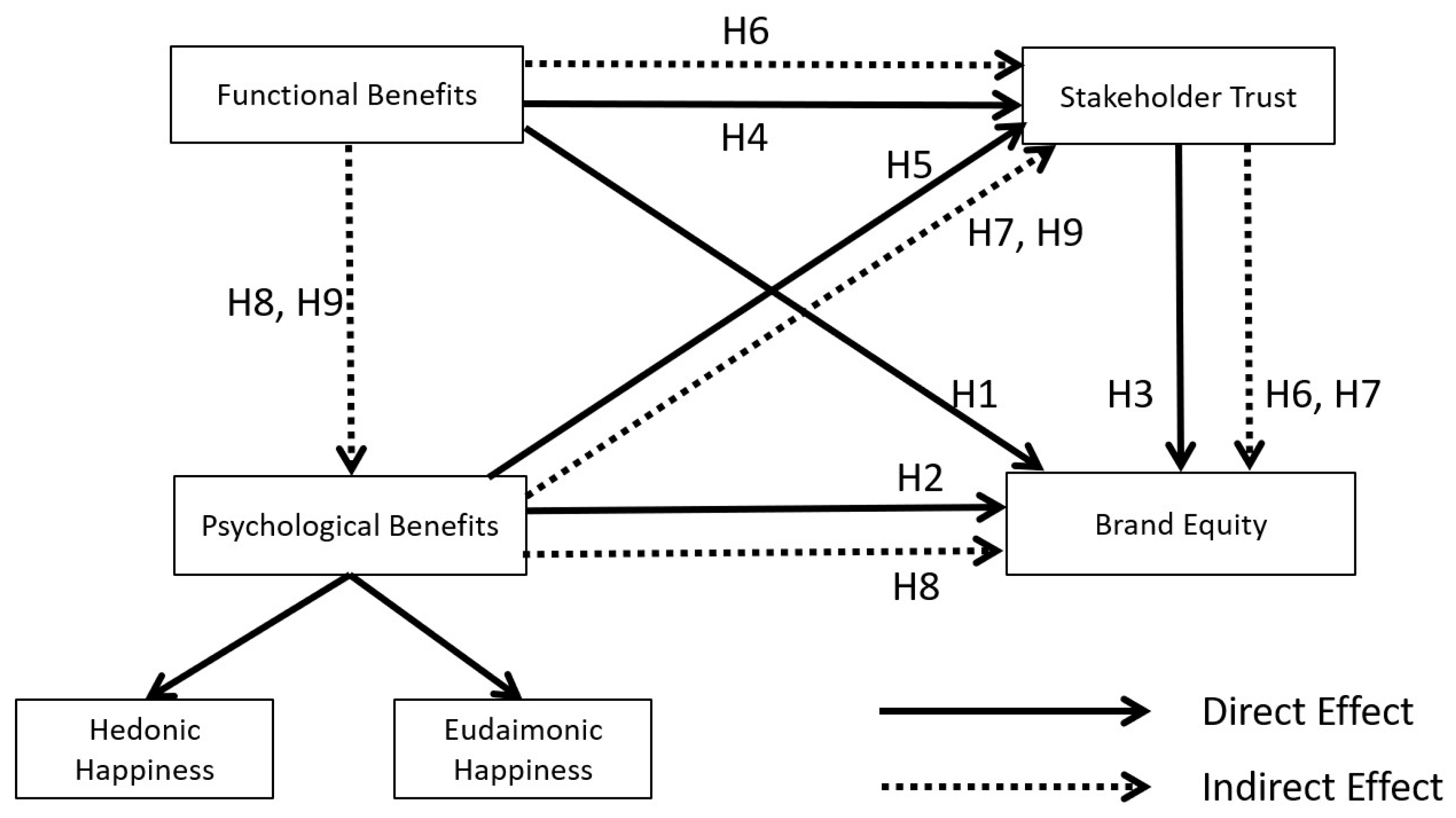

- What are stakeholder-relevant factors that lead to improving brand equity?

- How are these factors related?

- Do the factors create an impact differently among different groups of stakeholders?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Sustainability

2.2. Stakeholders

2.3. Stakeholder Benefits

2.4. Stakeholder Trust

2.5. Brand Equity

3. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Methodology Approach

4.2. Sampling

4.3. Measurement

4.4. Data Collection

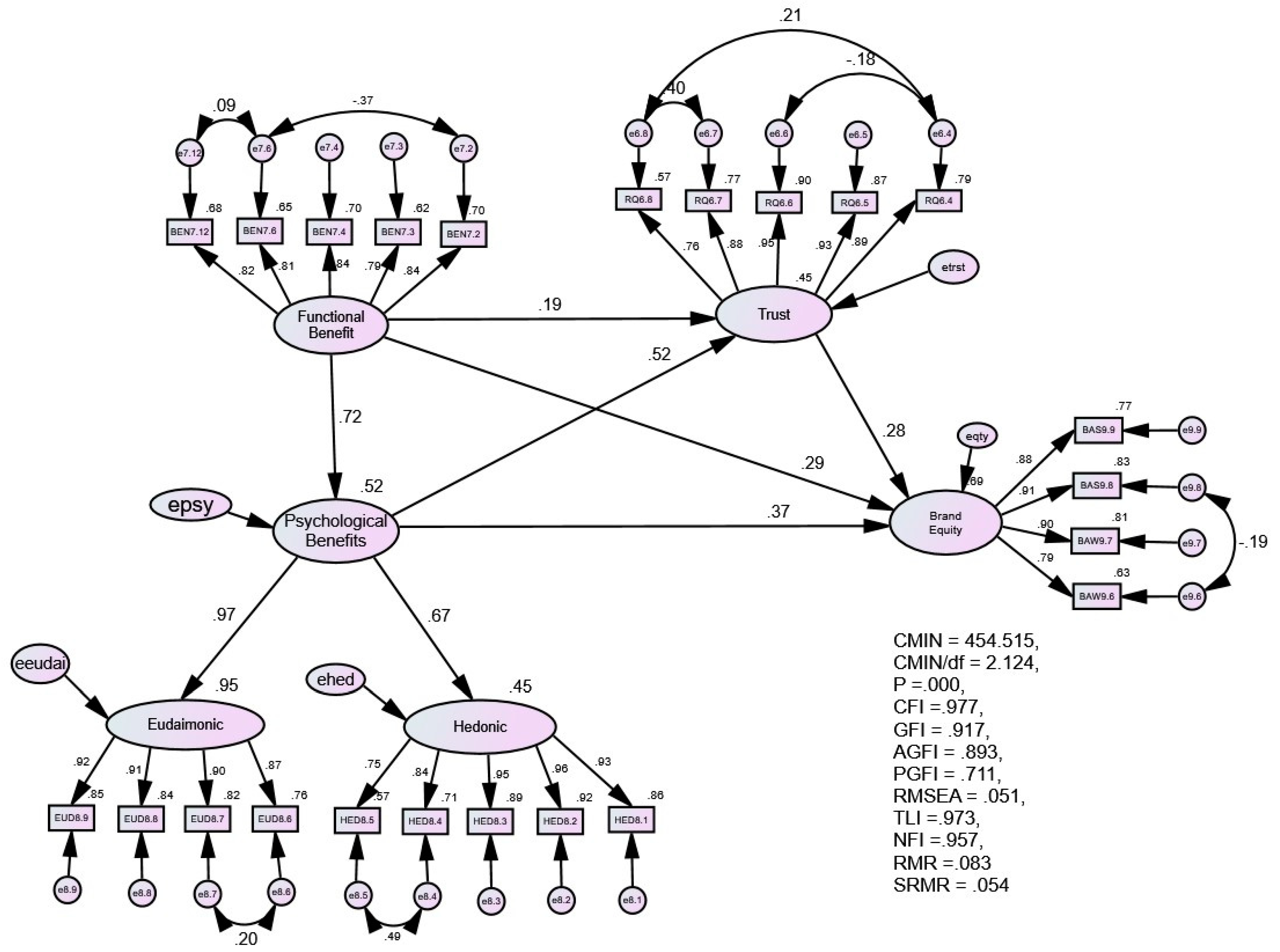

5. Data Analysis and Results

6. Discussion of the Findings

7. Managerial Implications

8. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Scale | Measured Items |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Functional benefits scale (Voss et al., 2003) | Practical vs. Impractical |

| Necessary vs. Unnecessary | ||

| Functional vs. Not functional | ||

| Helpful vs. Unhelpful | ||

| Effective vs. Ineffective | ||

| 2. | Hedonic happiness scale (Huta and Ryan, 2010) | Enjoyment |

| Pleasure | ||

| Fun | ||

| Relaxation | ||

| Take it easy | ||

| 3. | Eudaimonic happiness scale (Huta and Ryan, 2010) | Pursuing excellence or a personal ideal |

| Using the best in yourself | ||

| Develop a skill, learn or gain insight into something | ||

| Doing what you believe in | ||

| 4. | Stakeholder trust scale (Morgan and Hunt, 1994) | The company is perfectly honest and truthful |

| The company can be trusted completely | ||

| The company is always faithful | ||

| The company is someone that I have great confidence in | ||

| The company has high integrity | ||

| 5. | Brand equity scale (Hsu, 2012) | I can recognize this company among other competitors |

| I am aware of this company | ||

| Some characteristics of this company come to my mind quickly | ||

| I can quickly recall the symbol or logo of this company |

Appendix B

| CR | AVE | MSV | ASV | Cronbach α | CMIN | CMIN/df | P | CFI | TLI | NFI | RMSEA | SRMR | RMR | PGFI | GFI | AGFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Benefit | 0.911 | 0.671 | 0.520 | 0.385 | 0.907 | 5.088 | 1.696 | 0.165 | 0.998 | 0.995 | 0.996 | 0.040 | 0.011 | 0.018 | 0.199 | 0.995 | 0.976 |

| Hedonic | 0.949 | 0.788 | 0.425 | 0.283 | 0.951 | 5.769 | 1.442 | 0.217 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.032 | 0.006 | 0.009 | 0.265 | 0.995 | 0.981 |

| Eudaimonic | 0.946 | 0.815 | 0.560 | 0.471 | 0.949 | 0.405 | 0.405 | 0.524 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.100 | 1.000 | 0.995 |

| Trust | 0.945 | 0.776 | 0.707 | 0.359 | 0.949 | 0.462 | 0.231 | 0.794 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.133 | 1.000 | 0.997 |

| Brand Equity | 0.927 | 0.760 | 0.560 | 0.456 | 0.923 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.955 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Overall | 448.368 | 2.115 | 0.000 | 0.977 | 0.973 | 0.958 | 0.051 | 0.048 | 0.077 | 0.705 | 0.918 | 0.893 |

References

- Elkington, J. Accounting for the triple bottom line. Meas. Bus. Excell. 1998, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Practices for enhancing resilience and performance. In Sufficiency Thinking; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Sustainable leadership practices for enhancing business resilience and performance. Strat. Leadersh. 2011, 39, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kantabutra, S.; Ketprapakorn, N. Toward a theory of corporate sustainability: A theoretical integration and exploration. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baalbaki, S.; Guzmán, F. A consumer-perceived consumer-based brand equity scale. J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The Drivers of Green Brand Equity: Green Brand Image, Green Satisfaction, and Green Trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. The Value of Brand Equity. J. Bus. Strategy 1992, 13, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, W.; MacDonald, C. Getting to the bottom of “triple bottom line”. Bus. Ethics Q. 2004, 14, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boukis, A.; Christodoulides, G. Investigating Key Antecedents and Outcomes of Employee-based Brand Equity. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020, 17, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.-T. The Advertising Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Reputation and Brand Equity: Evidence from the Life Insurance Industry in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-S.; Chiu, C.-J.; Yang, C.-F.; Pai, D.-C. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Performance: The Mediating Effect of Industrial Brand Equity and Corporate Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.F.; Butt, M.M.; Khong, K.W.; Ong, F.S. Antecedents of Green Brand Equity: An Integrated Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, F.; Davis, D. The impact of corporate social responsibility on brand equity: Consumer responses to two types of fit. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2017, 26, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Hur, W.-M. Investigating the Antecedents of Green Brand Equity: A Sustainable Development Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Nayak, J.K. Consumer psychological motivations to customer brand engagement: A case of brand community. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R. Brand credibility and brand involvement as an antecedent of brand equity: An empirical study. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. 2012, 3, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kantabutra, S.; Ketprapakorn, N. Toward an Organizational Theory of Resilience: An Interim Struggle. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervitsiotis, K.N. Beyond stakeholder satisfaction: Aiming for a new frontier of sustainable stakeholder trust. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2003, 14, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.; Schmidpeter, R.; Habisch, A. Assessing Social Capital: Small and Medium Sized Enterprises in Germany and the UK. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 47, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Baldo, M. Corporate social responsibility and corporate governance in Italian SMEs: The experience of some “spirited businesses”. J. Manag. Gov. 2012, 16, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S. Measuring corporate sustainability: A Thai approach. Meas. Bus. Excel. 2014, 18, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S.; Siebenhüner, T. Predicting Corporate Sustainability: A Thai Approach. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2011, 27, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S. Putting Rhineland principles into practice in Thailand: Sustainable leadership at Bathroom Design Company. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excel. 2012, 31, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S.; Avery, G.C. Sustainable leadership at Siam Cement Group. J. Bus. Strat. 2011, 32, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kantabutra, S.; Suriyankietkaew, S. Sustainable leadership: Rhineland practices at a Thai small enterprise. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2013, 19, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S. Toward an Organizational Theory of Sustainability Vision. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vongariyajit, N.; Kantabutra, S. A Test of the Sustainability Vision Theory: Is It Practical? Sustainability 2021, 13, 7534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P.P.; Jalal, K.F.; Boyd, J.A. Sustainable development indicators. In An Introduction to Sustainable Development; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Honeybees & Locusts: The Business Case for Sustainable Leadership; Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, NSW, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Esa, E.; Zahari, A.R.; Nawang, D. Corporate Sustainability Reporting, Ownership Structure and Brand Equity. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.-B.; Lee, J. Exploring the differential impact of environmental sustainability, operational efficiency, and corporate reputation on market valuation in high-tech-oriented firms. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 211, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, A.; Vidovic, M. Sustainability Performance and Assurance: Influence on Reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2015, 18, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D.; Sen, S. Strengthening Stakeholder–Company Relationships Through Mutually Beneficial Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaningsih, E.S. The Impact of CSR Awareness and CSR Beliefs on Corporate Reputation and Brand Equity: Evidence from Indonesia. Int. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 11, 530–536. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, W.-M.; Kim, H.; Woo, J. How CSR Leads to Corporate Brand Equity: Mediating Mechanisms of Corporate Brand Credibility and Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 125, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. A Stakeholder Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility: A Fresh Perspective into Theory and Practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holme, R.; Watts, P. Corporate Social Responsibility: Making Good Business Sense; World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD): Conches-Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Gardberg, N.A.; Barnett, M.L. Opportunity Platforms and Safety Nets: Corporate Citizenship and Reputational Risk. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2000, 105, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, S.N. The stakeholder theory of the firm and organizational decision making: Some propositions and a model. Proc. Int. Assoc. Bus. Soc. 1993, 4, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.Y.; Kwan, C.L. The effect of environmental, social, governance and sustainability initiatives on stock value–Examining market response to initiatives undertaken by listed companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. A holistic perspective on corporate sustainability drivers. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, R.M.; Franks, D.M.; Ali, S.H. Sustainability certification schemes: Evaluating their effectiveness and adaptability. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2016, 16, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasni, M.J.S.; Salo, J.; Naeem, H.; Abbasi, K.S. Impact of internal branding on customer-based brand equity with mediating effect of organizational loyalty: An empirical evidence from retail sector. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N. Testing cross-cultural invariance of the brand equity creation process. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2002, 11, 380–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winit, W.; Kantabutra, S. Sustaining Thai SMEs through perceived benefits and happiness. Manag. Res. Rev. 2017, 40, 556–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Sustainable Leadership: Honeybee and Locust Approaches; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, R.; Freeman, R.E.; Wicks, A.C. What Stakeholder Theory Is Not. Bus. Ethics Q. 2003, 13, 479–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.; Ferrell, L. A stakeholder model for implementing social responsibility in marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 956–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chandon, P.; Wansink, B.; Laurent, G. A Benefit Congruency Framework of Sales Promotion Effectiveness. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Nagao, K.; He, Y.; Morgan, F.W. Satisfiers, Dissatisfiers, Criticals, and Neutrals: A Review of Their Relative Effects on Customer (Dis)Satisfaction. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2007, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Eberle, D.; Berens, G.; Li, T. The Impact of Interactive Corporate Social Responsibility Communication on Corporate Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, R.-T. Modeling Corporate Social Performance and Job Pursuit Intention: Mediating Mechanisms of Corporate Reputation and Job Advancement Prospects. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 117, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Wilson, J. Volunteer Work and Hedonic, Eudemonic, and Social Well-Being. Sociol. Forum 2012, 27, 658–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Broyles, S.A.; Schumann, D.W.; Leingpibul, T. Examining Brand Equity Antecedent/Consequence Relationships. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Parameswaran, M.; Jacob, I. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity; Pearson Education: New Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Singh, J.J.; Sierra, V. Do Customer Perceptions of Corporate Services Brand Ethicality Improve Brand Equity? Considering the Roles of Brand Heritage, Brand Image, and Recognition Benefits. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, M.; Van Buren, H.J., III. Trust and stakeholder theory: Trustworthiness in the organisation–stakeholder relationship. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S. Exploring relationships among sustainability organizational culture components at a leading asian industrial conglomerate. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markland, R.E.; Vickery, S.K.; Davis, R.A. Operations Management: Concepts in Manufacturing and Services; West Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrand, B.; Driessen, P.H.; Koll, O. Stakeholder marketing: Theoretical foundations and required capabilities. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vallaster, C.; von Wallpach, S. An online discursive inquiry into the social dynamics of multi-stakeholder brand meaning co-creation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davcik, N.S.; da Silva, R.V.; Hair, J.F. Towards a unified theory of brand equity: Conceptualizations, taxonomy and avenues for future research. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merz, M.A.; He, Y.; Vargo, S.L. The evolving brand logic: A service-dominant logic perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 37, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaiger, M.; Sarstedt, M. Corporate branding in a turbulent environment. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 19, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morgan, R.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloutsou, C. Brand evaluation, satisfaction and trust as predictors of brand loyalty: The mediator-moderator effect of brand relationships. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.B.; Kim, W.G.; An, J.A. The effect of consumer-based brand equity on firms’ financial performance. J. Consum. Mark. 2003, 20, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, V.R.; Agarwal, M.K.; Dahlhoff, D. How is manifest branding strategy related to the intangible value of a corporation? J. Mark. 2004, 68, 126–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, A.; Roy, M.; Donaldson, C. Re-imagining social enterprise. Soc. Enterp. J. 2016, 12, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S. Exploring a Thai ‘sufficiency’ approach to corporate sustainability. Int. J. Bus. Excell. 2019, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Avery, G. Leadership practices influencing stakeholder satisfaction in Thai SMEs. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2014, 6, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G.; Moran, P. Corporate Reputations: Built in or Bolted on? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2012, 54, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudambi, S.M.; Doyle, P.; Wong, V. An exploration of branding in industrial markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1997, 26, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of A Brand Name; The Free Press: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Konuk, F.A.; Rahman, S.U.; Salo, J. Antecedents of green behavioral intentions: A cross-country study of T urkey, F inland and P akistan. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Corporate social responsibility, leadership, and brand equity in healthcare service. Soc. Responsib. J. 2012, 8, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Munuera-Alemán, J.L. Does brand trust matter to brand equity? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belenioti, Z.-C.; Vassiliadis, C.A. Social media impact on NPO brand equity: Conceptualizing the trends and prospects. In Proceedings of the 10th Annual Conference of the EuroMed Academy of Business, Rome, Italy, 13–15 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Belenioti, Z.-C.; Tsourvakas, G.; Vassiliadis, C.A. Do Social Media Affect Museums’ Brand Equity? An Exploratory Qualitative Study. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenioti, Z.-C.; Tsourvakas, G.; Vassiliadis, C.A. Museums Brand Equity and Social Media: Looking into Current Research Insights and Future Research Propositions. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1215–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Broyles, S.A.; Leingpibul, T.; Ross, R.H.; Foster, B.M. Brand equity’s antecedent/consequence relationships in cross-cultural settings. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2010, 19, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Collis, J.; Hussey, R. Business Research: A Practical Guide for Students; Red Globe Press: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.S.; Konge, L.; Artino, A.R. The Positivism Paradigm of Research. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.E.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the Hedonic and Utilitarian Dimensions of Consumer Attitude. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V.; Ryan, R.M. Pursuing Pleasure or Virtue: The Differential and Overlapping Well-Being Benefits of Hedonic and Eudaimonic Motives. J. Happiness Stud. 2010, 11, 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, F.J., Jr. Applied Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrakas, P.J. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krumpal, I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 2025–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H.A.; Simmering, M.J.; Sturman, M.C. A tale of three perspectives: Examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organ. Res. Methods 2009, 12, 762–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M.; Jensen, R. Common Method Bias in Public Management Studies. Int. Public Manag. J. 2014, 18, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Methodology in the Social Sciences. In Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X. Structural Equation Modeling Applications Using Mplus; Wiley/Higher Education Press: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS for Windows; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2014, 67, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketprapakorn, N. Toward an Asian corporate sustainability model: An integrative review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 117995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.S.; Dash, S.; Purwar, P.C. The nature and antecedents of brand equity and its dimensions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2013, 31, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Johnson, L.W.; Wilkie, D.C.; De Araujo-Gil, L. Consumer emotional brand attachment with social media brands and social media brand equity. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 1176–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Stakeholder Management: Framework and Philosophy; Pitman: Mansfield, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

| Geographical Distribution of Respondents | Customers | Employees | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bangkok (Capital City) | 48 (22.4%) | 78 (35.6%) | 126 (29.1%) |

| Central Thailand | 54 (25.2%) | 79 (36.1%) | 133 (30.7%) |

| Northern | 59 (27.6%) | 54 (24.7%) | 113 (26.1%) |

| Eastern | 14 (6.5%) | 7 (3.2%) | 21 (4.8%) |

| Northeastern | 18 (8.4%) | 1 (0.5%) | 19 (4.4%) |

| Southern | 21 (9.8%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (4.8%) |

| Total | 214 (49%) | 219 (51%) | 433 (100.0%) |

| Relationship Period with the Firm | Customers | Employees | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 Year | 25.7% | 11.5% | 18.5% |

| 1–3 Years | 31.3% | 25.2% | 28.2% |

| 4–6 Years | 17.8% | 20.2% | 19.0% |

| 7–9 Years | 7.0% | 17.9% | 12.5% |

| 10 Years and Over | 18.2% | 25.2% | 21.8% |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Observed Relationships | Estimate | Standardized Regression Weights | S.E. | CR | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEQ ← FB | 0.268 | 0.29 | 0.051 | 5.213 | *** | Supported H1 |

| BEQ ← PB | 0.46 | 0.372 | 0.083 | 5.56 | *** | Supported H2 |

| BEQ ← T | 0.237 | 0.285 | 0.039 | 6.028 | *** | Supported H3 |

| PB ← FB | 0.538 | 0.722 | 0.05 | 10.774 | *** | |

| T ← FB | 0.214 | 0.192 | 0.078 | 2.747 | 0.006 | Supported H4 |

| T ← PB | 0.772 | 0.518 | 0.112 | 6.883 | *** | Supported H5 |

| Hed ← PB | 1 | 0.67 | ||||

| Eud ← PB | 1.352 | 0.973 | 0.105 | 12.865 | *** |

| Observed Indirect Path | Unstandardized Estimate | Lower | Upper | p-Value | Standardized Estimate | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEQ ← T ← FB | 0.051 | 0.013 | 0.111 | 0.018 | 0.055 * | Supported H6 |

| BEQ ← T ← PB | 0.183 | 0.115 | 0.267 | 0.001 | 0.147 *** | Supported H7 |

| BEQ ← PB ← FB | 0.248 | 0.174 | 0.352 | 0.001 | 0.269 *** | Supported H8 |

| T ← PB ← FB | 0.415 | 0.296 | 0.561 | 0.001 | 0.374 ** | Supported H9 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Winit, W.; Kantabutra, S. Enhancing the Prospect of Corporate Sustainability via Brand Equity: A Stakeholder Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4998. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094998

Winit W, Kantabutra S. Enhancing the Prospect of Corporate Sustainability via Brand Equity: A Stakeholder Model. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):4998. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094998

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinit, Warat, and Sooksan Kantabutra. 2022. "Enhancing the Prospect of Corporate Sustainability via Brand Equity: A Stakeholder Model" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 4998. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094998

APA StyleWinit, W., & Kantabutra, S. (2022). Enhancing the Prospect of Corporate Sustainability via Brand Equity: A Stakeholder Model. Sustainability, 14(9), 4998. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094998