Corruption as a Moderator in the Relationship between E-Government and Inward Foreign Direct Investment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

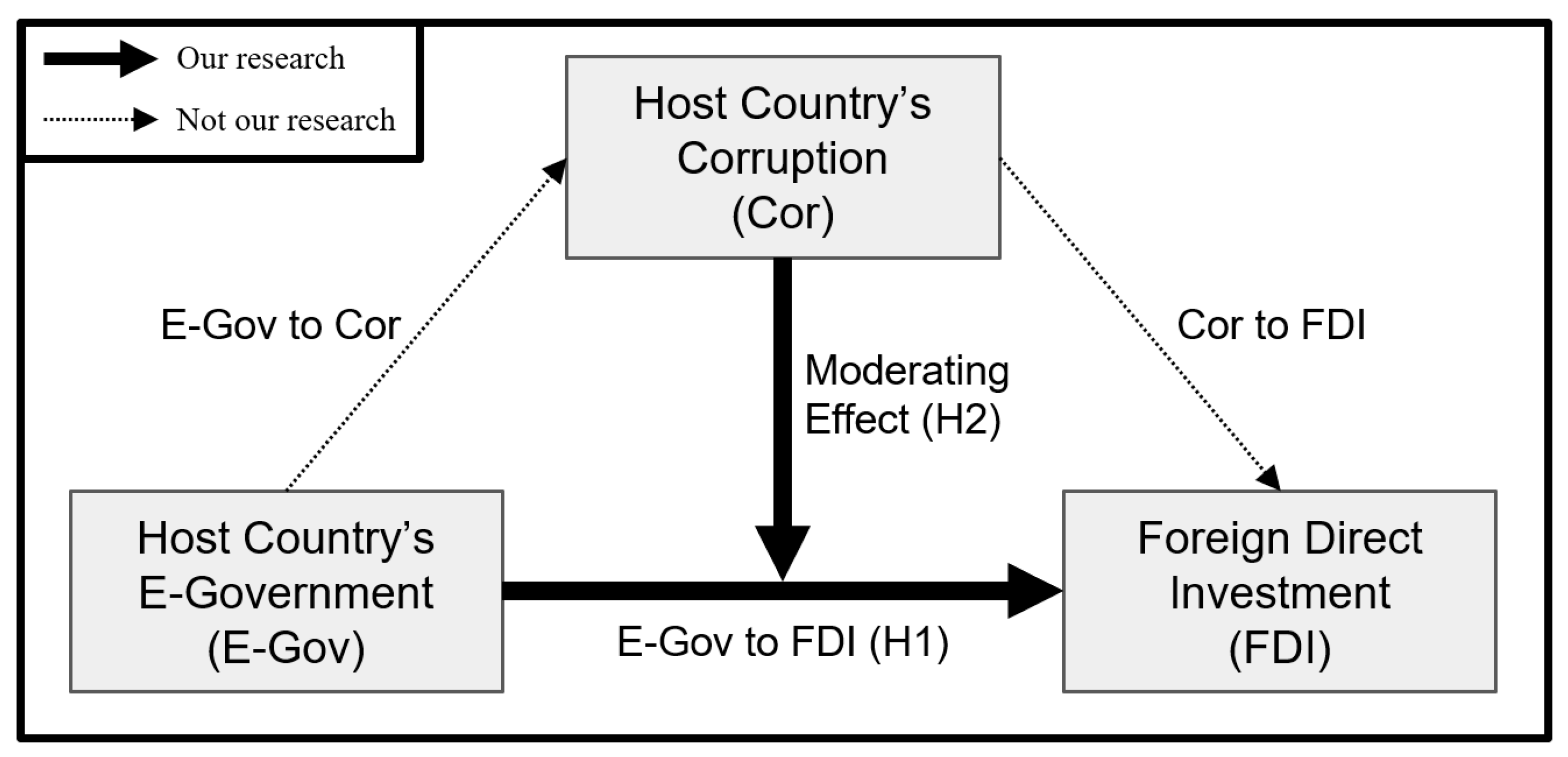

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.1. FDI, Information, and E-Government

2.2. Hypotheses Development

3. Data Description

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Bilateral FDI Flow

3.2.2. E-Government Quality

3.2.3. Corruption Level

3.3. Control Variables

4. Methods and Results

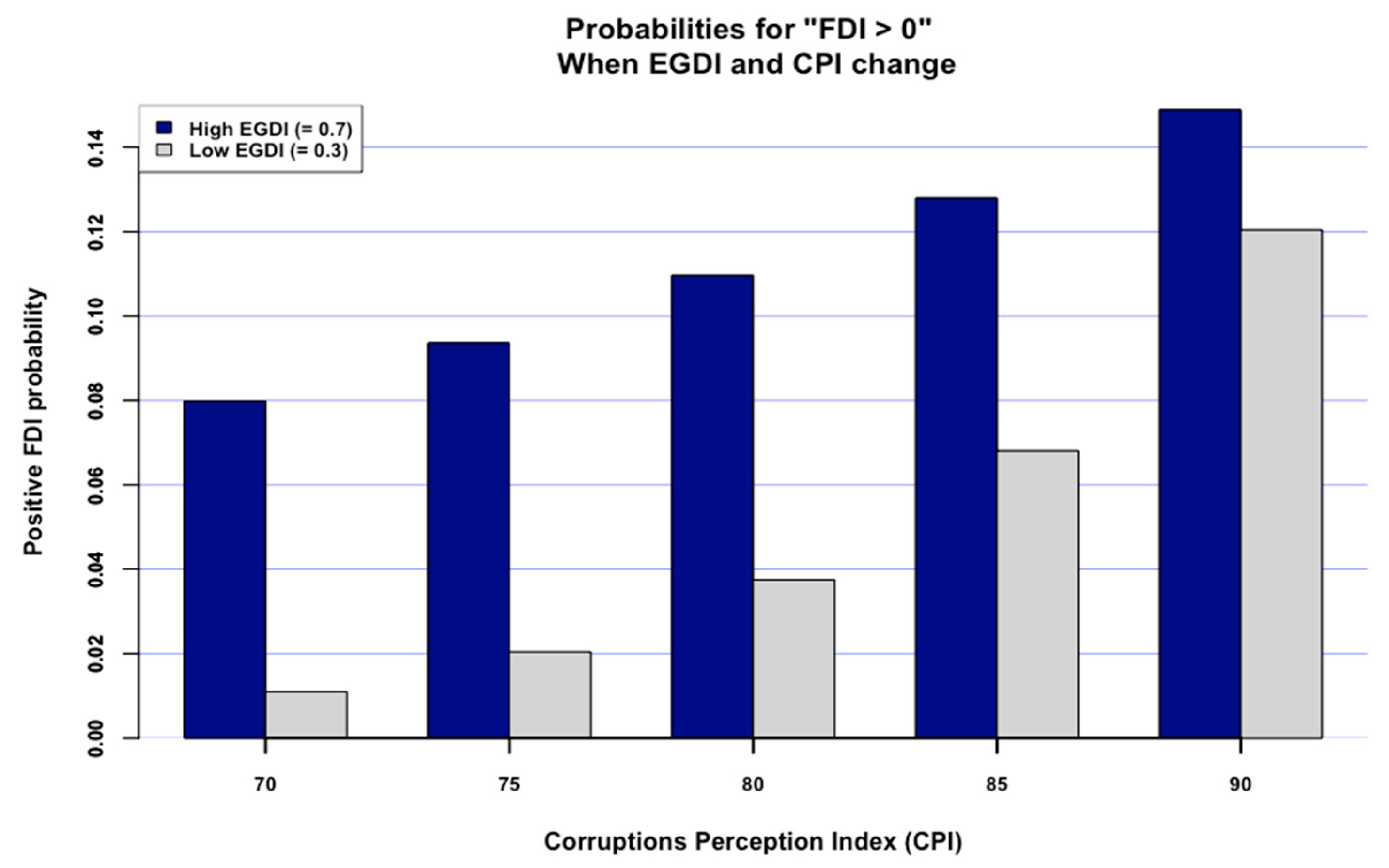

4.1. Main Results

4.2. Robustness Check

4.3. Additional Analysis 1

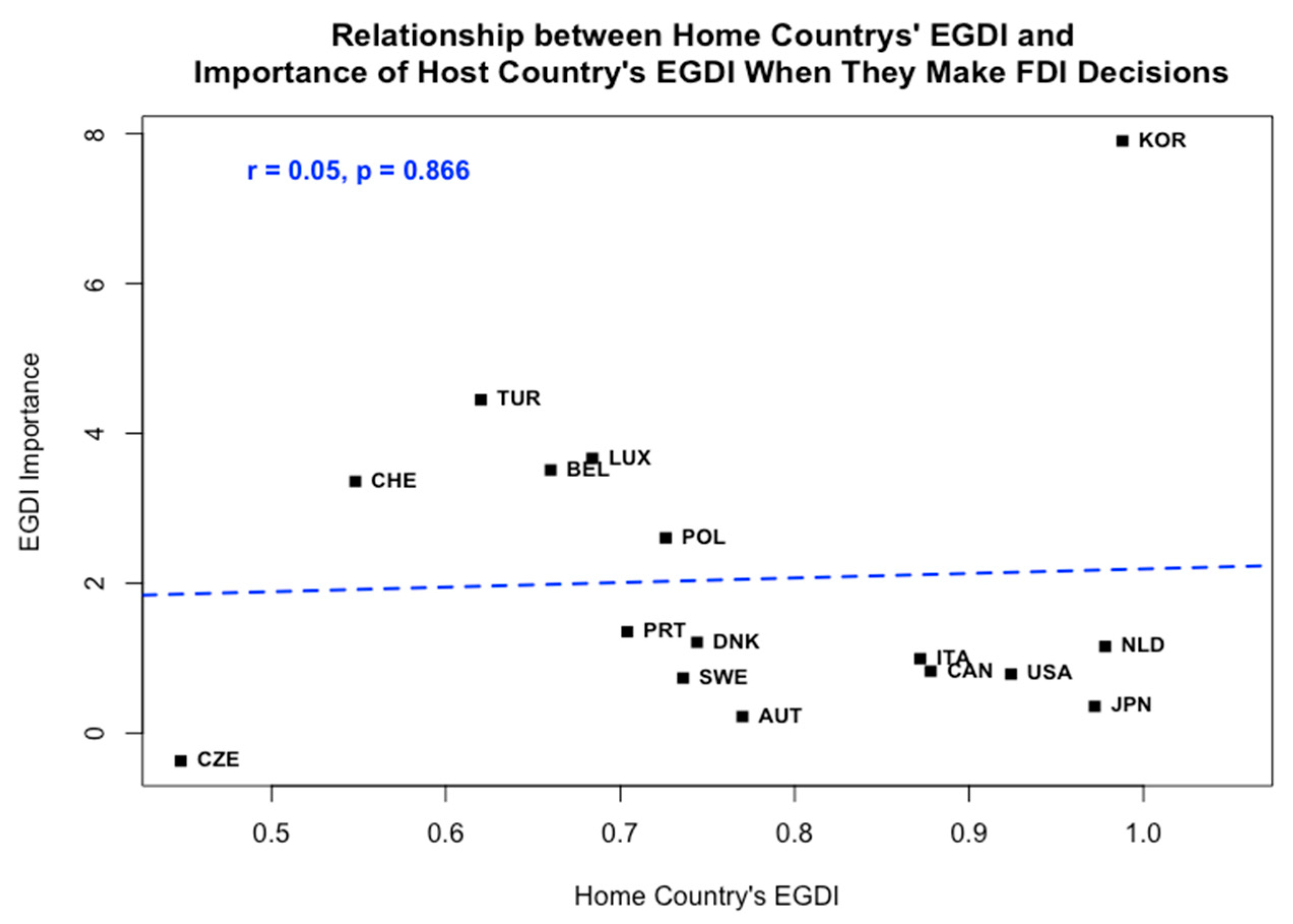

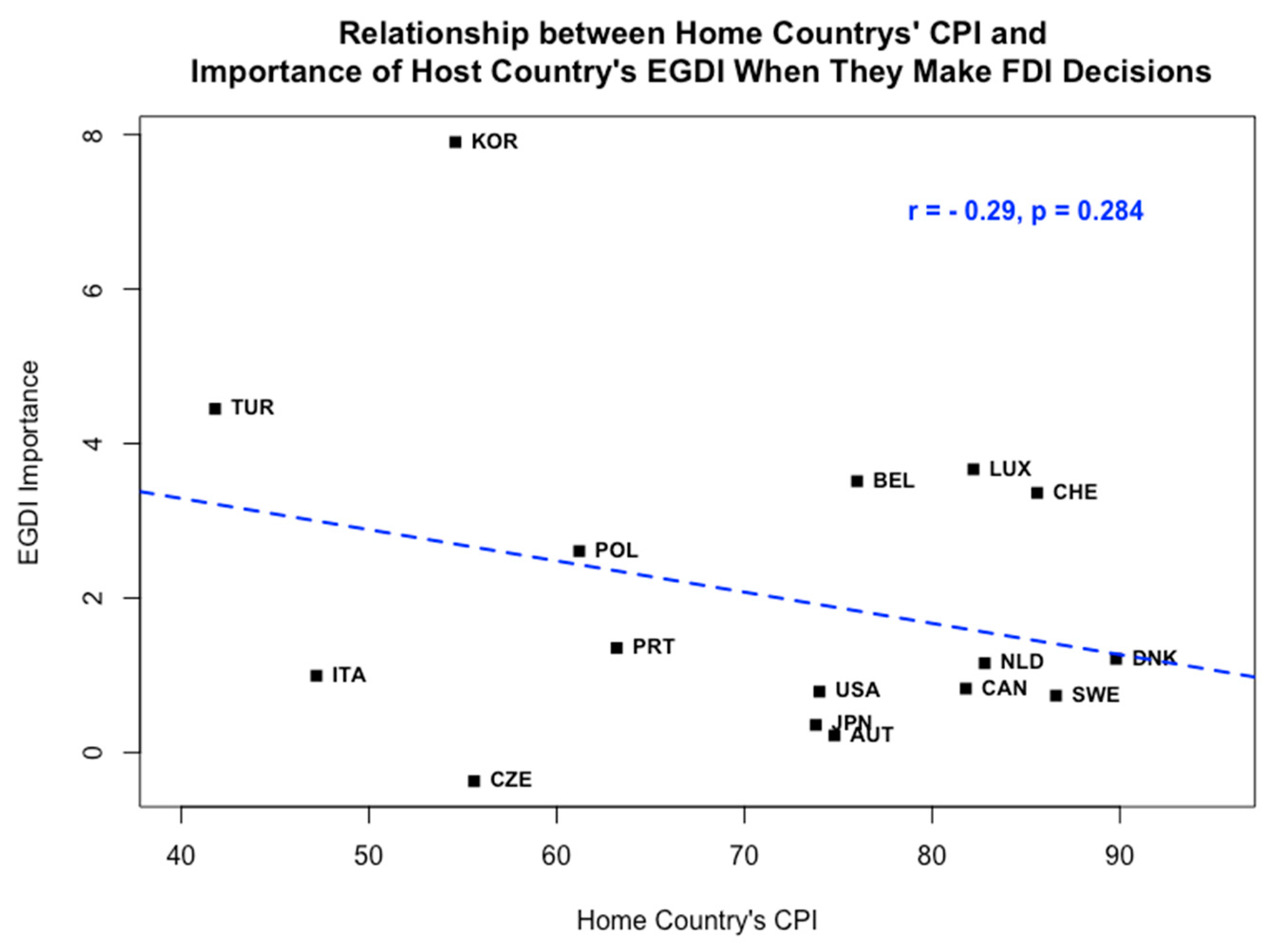

4.4. Additional Analysis 2

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfaro, L.; Chanda, A.; Kalemli-Ozcan, S.; Sayek, S. FDI and Economic Growth: The Role of Local Financial Markets. J. Int. Econ. 2004, 64, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonigen, B.A. A Review of the Empirical Literature on FDI Determinants. Atl. Econ. J. 2005, 33, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.E. Perspectives on Multinational Enterprises in Emerging Economies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Feliciano-Cestero, M.M. Five Decades of Research on Foreign Direct Investment by MNEs: An Overview and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah-Kubi, S.N.; Malec, K.; Maitah, M.; Kutin, S.B.; Pánková, L.; Phiri, J.; Zaganjori, O. The impact of corporate governance structures on foreign direct investment: A case study of West African countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. The effects of foreign direct investment, economic growth, industrial structure, renewable and nuclear energy, and urbanization on Korean greenhouse gas emissions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yue, S.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y. Does foreign direct investment affect green growth? Evidence from China’s experience. Sustainability 2016, 8, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, K. Influence of urbanization and foreign direct investment on carbon emission efficiency: Evidence from urban clusters in the Yangtze River economic belt. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. International Direct Investment Statistics 2019; OECD Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Driffield, N.; Jones, C.; Crotty, J. International Business Research and Risky Investments, an Analysis of FDI in Conflict Zones. Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 22, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunning, J.H. Internationalizing Porter’s Diamond. MIR Manag. Int. Rev. 1993, 33, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, M.; Zurawicki, L. Corruption and Foreign Direct Investment. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouthers, L.E.; Gao, Y.; McNicol, J.P. Corruption and Market Attractiveness Influences on Different Types of FDI. Strat. Mgmt. J. 2008, 29, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J. Forbidden Payment: Foreign Bribery and American Business after 1977; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, D.; Mody, A. International Investment Location Decisions. J. Int. Econ. 1992, 33, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose–Ackerman, S. Corruption and Government. Int. Peacekeeping 2008, 15, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.J.; Ding, Y.; Kim, C. High-Level Politically Connected Firms, Corruption, and Analyst Forecast Accuracy around the World. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 1505–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javorcik, B.S.; Wei, S.-J. Corruption and Cross-Border Investment in Emerging Markets: Firm-Level Evidence. J. Int. Money Financ. 2009, 28, 605–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyer, P.A.; Beamish, P.W. The Effect of Corruption on Japanese Foreign Direct Investment. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 50, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.-J. How Taxing Is Corruption on International Investors? Rev. Econ. Stat. 2000, 82, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoinaru, R.; Buda, D.; Borlea, S.N.; Văidean, V.L.; Achim, M.V. The impact of corruption and shadow economy on the economic and sustainable development. Do they “sand the wheels” or “grease the wheels”? Sustainability 2020, 12, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, F. Corruption, economic development and haze pollution: Evidence from 139 global countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feruni, N.; Hysa, E.; Panait, M.; Rădulescu, I.G.; Brezoi, A. The impact of corruption, economic freedom and urbanization on economic development: Western Balkans versus EU-27. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nationen, V. (Ed.) E-Government in Support of Sustainable Development; United Nations e-Government Survey: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, C.N.; Chung, C.J. Big Data Analysis of Local Government 3.0: Focusing on Gyeongsangbuk-Do in Korea. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 110, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wescott, C. Combating Corruption in Southeast Asia. In Fighting Corruption in ASIA: Causes, Effects and Remedies; World Scientific: Singapore, 2003; pp. 237–269. [Google Scholar]

- Global Corruption Report; Transparency International: Berlin, Germany, 2018.

- Anderson, J. A Review of Governance and Anti-Corruption Indicators in East Asia and Pacific; World Bank: Washington, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry, J.J.; Jalal, A. An Empirical Analysis of the Relationship between E-Government and Corruption. Int. J. Digit. Account. Res. 2012, 12, 145–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, D.C.; Eom, T.H. E-Government and Anti-Corruption: Empirical Analysis of International Data. Int. J. Public Adm. 2008, 31, 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, A.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N.; Bukhari, M.H. Assessing the moderating effect of corruption on the e-government and trust relationship: An evidence of an emerging economy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, C.C.; García-Sánchez, I.M.; Vicente-Galindo, P.; Galindo-Villardón, P. Exploring Relationships between Environmental Performance, E-Government and Corruption: A Multivariate Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myeong, S.; Kwon, Y.; Seo, H. Sustainable e-governance: The relationship among trust, digital divide, and e-government. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6049–6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.B. Exploring the relationship between E-government development and environmental sustainability: A study of small Island Developing States. Sustainability 2017, 9, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anechiarico, F.; Jacobs, J.B. The Pursuit of Absolute Integrity: How Corruption Control Makes Government Ineffective; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Azubuike, A. Accessibility of government information as a determinant of inward foreign direct investment in Africa. In Proceedings of the World Library and Information Congress: 72nd IFLA General Conference and Council, Seoul, Korea, 20–24 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kachwamba, M.A. Impact of E-Government on Transaction Cost and FDI Inflows: A Proposed Conceptual Framework. IJBM 2011, 6, p285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prasetyo, B.; Susanto, T.D. The Relationship Analysis of E-Government Implementation on Increasing Capital Investment in Region (Case Study: Banyuwangi City). IPTEK J. Eng. 2017, 3, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abu-Shanab, E. Antecedents of Trust in E-Government Services: An Empirical Test in Jordan. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2014, 8, 480–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Veiga, L. Electronic Government and the Ease of Doing Business. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Galway, Ireland, 4–6 April 2018; pp. 584–587. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, J.H. Toward an Eclectic Theory of International Production: Some Empirical Tests. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1980, 11, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.H. The Eclectic Paradigm of International Production: A Restatement and Some Possible Extensions. In The Eclectic Paradigm; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 50–84. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, A.; Hua, X.; Uddin, M.; Du, M. Home Country Macroeconomic Factors on Outward Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions: Evidence from the UK. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2014, 30, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiymaz, H. The Impact of Country Risk Ratings on U.S. Firms in Large Cross-Border Acquisitions. Glob. Financ. J. 2009, 20, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, L.; Miller, S.R. Distance Matters: Liability of Foreignness, Institutional Distance and Ownership Strategy. In Advances in International Management; Emerald (MCB UP): Bingley, UK, 2004; Volume 16, pp. 187–221. [Google Scholar]

- Grosse, R.; Trevino, L.J. New Institutional Economics and FDI Location in Central and Eastern Europe. MIR: Manag. Int. Rev. 2005, 45, 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations; Foundations for Organizational Science; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. A Transaction Cost Theory of Politics. J. Theor. Politics 1990, 2, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostova, T. Country Institutional Profiles: Concept and Measurement. AMPROC 1997, 1997, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, F.L.; Napolitano, F.; Tissi, N.E. FDI in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Longitudinal Perspective on Location-Specific Factors (2003–2010). Int. Bus. Rev. 2014, 23, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, S. Overcoming the Liability of Foreignness. AMJ 1995, 38, 341–363. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskisson, R.E.; Eden, L.; Lau, C.M.; Wright, M. Strategy in Emerging Economies. AMJ 2000, 43, 249–267. [Google Scholar]

- Mudambi, R.; Navarra, P. Institutions and Internation Business: A Theoretical Overview. Int. Bus. Rev. 2002, 11, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, I.; Razin, A. An Information-Based Trade off between Foreign Direct Investment and Foreign Portfolio Investment. J. Int. Econ. 2006, 70, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graham, B.A.T.; Johnston, N.P.; Kingsley, A.F. Even Constrained Governments Take: The Domestic Politics of Transfer and Expropriation Risks. J. Confl. Resolut. 2018, 62, 1784–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A. Understanding Modern Transparency. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2009, 75, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matambalya, F.; Wolf, S. The role of ICT for the Performance of SMEs in East Africa. Empirical Evidence from Kenya and Tanzania; University of Bonn, Center for Development Research (ZEF): Bonn, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brin, S. Extracting Patterns and Relations from the World Wide Web. In The World Wide Web and Databases; Atzeni, P., Mendelzon, A., Mecca, G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 1590, pp. 172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Prattipati, S.N. Adoption of E-Governance: Differences between Countries in the Use of Online Government Services. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2003, 3, 386–401. [Google Scholar]

- Fatima, S.T. Productivity Spillovers from Foreign Direct Investment: Evidence from Turkish Micro-Level Data. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2016, 25, 291–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Kui, Z.; Ullah, S.; Pinglu, C.; Khan, S. Sustainable utilization of financial and institutional resources in reducing income inequality and poverty. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneuer, M. E-Democracy: A New Challenge for Measuring Democracy. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2016, 37, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, T.A.; Nam, T.; Burke, G.B. E-Government Interoperability: Interaction of Policy, Management, and Technology Dimensions. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2012, 30, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, E. How Much Is Really Known About the Meaning of the Term “Conflict of Interest”? Int. J. Public Adm. 2013, 36, 884–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, K.W.; Singh, H. The Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment: New Empirical Evidence. Transnatl. Corp. 1996, 5, 67–106. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, L.T.; Wint, A.G. Marketing a Country: Promotion as a Tool for Attracting Foreign Investment; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Globerman, S.; Shapiro, D. Governance Infrastructure and US Foreign Direct Investment. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2003, 34, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinez, J.R.; Liu, L. Corruption Distance and FDI Flows into Latin America. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ITU. World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database; International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, J.H. Location and the Multinational Enterprise: John Dunning’s Thoughts on Receiving the Journal of International Business Studies 2008 Decade Award. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neter, J.; Kutner, M.H.; Nachtsheim, C.J.; Wasserman, W. Applied Linear Statistical Models; Irwin: Huntersville, NC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Studenmund, A.H.; Cassidy, H.J. Using Econometrics: A Practical Guide; Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) FDI (1 if positive, or 0) | 0.18 | 0.39 | |||||||

| (2) Log GDP | 27.35 | 1.29 | 0.49 *** | ||||||

| (3) TPG | 111.14 | 83.31 | −0.24 *** | −0.72 *** | |||||

| (4) GPC | 44,670.34 | 25,003.34 | −0.01 | −0.19 *** | 0.63 *** | ||||

| (5) POLI | 0.72 | 0.68 | −0.07 * | −0.25 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.54 *** | |||

| (6) MOB | 122.22 | 16.39 | 0.00 | −0.12 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.38 *** | ||

| (7) CPI | 70.69 | 14.52 | −0.05 † | −0.11 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.72 *** | 0.69 *** | 0.07 * | |

| (8) EGDI | 0.77 | 0.19 | 0.37 *** | 0.52 *** | −0.26 *** | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.06 * | 0.06 * |

| E-Government Development Index (2014–2018) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Rank | Country | Mean |

| 1 | KOR | 0.99 |

| 2 | NDL | 0.98 |

| 3 | USA | 0.92 |

| 4 | JPN | 0.91 |

| 5 | CAN | 0.82 |

| 6 | SWE | 0.72 |

| 7 | ITA | 0.7 |

| 8 | DNK | 0.69 |

| 9 | AUT | 0.66 |

| 10 | PRT | 0.61 |

| 11 | LUX | 0.6 |

| 12 | POL | 0.57 |

| 13 | BEL | 0.51 |

| 14 | CHE | 0.49 |

| 15 | TUR | 0.46 |

| 16 | CZE | 0.39 |

| Dependent Variable: Positive FDI Inflow or Not | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

| Control variables | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −47.51 *** | (4.331) | −47.29 *** | (4.382) | −32.52 *** | (4.718) | −31.99 *** | (4.803) | −34.42 *** | (5.061) |

| Log GDP | 1.658 *** | (0.153) | 1.655 *** | (0.155) | 1.107 *** | (0.168) | 1.095 *** | (0.171) | 1.201 *** | (0.181) |

| TPG | 0.013 *** | (0.003) | 0.013 *** | (0.003) | 0.006 † | (0.004) | 0.006 | (0.004) | 0.008 * | (0.004) |

| GPC | −0.000 * | (0.000) | −0.000 | (0.000) | 0.000 | (0.000) | 0.000 | (0.000) | −0.000 | (0.000) |

| POLI | 0.018 | (0.174) | 0.171 | (0.244) | −0.381 † | (0.203) | −0.179 | (0.274) | −0.456 | (0.316) |

| MOB | 0.002 | (0.005) | −0.002 | (0.007) | 0.002 | (0.006) | −0.002 | (0.007) | −0.003 | (0.007) |

| Partner country fixed effects | ||||||||||

| BEL | −1.635 ** | (0.541) | −1.636 ** | (0.540) | −1.697 ** | (0.538) | −1.697 ** | (0.537) | −1.735 ** | (0.545) |

| CAN | −0.918 † | (0.491) | −0.912 † | (0.492) | −0.974 † | (0.502) | −0.966 † | (0.503) | −1.003 * | (0.511) |

| CHE | −1.003 * | (0.487) | −1.003 * | (0.487) | −1.072 * | (0.495) | −1.073 * | (0.496) | −1.095 * | (0.504) |

| CZE | −1.866 *** | (0.557) | −1.861 *** | (0.556) | −1.902 *** | (0.552) | −1.898 *** | (0.551) | −1.949 *** | (0.557) |

| DNK | −0.763 | (0.468) | −0.766 | (0.468) | −0.803 † | (0.482) | −0.809 † | (0.483) | −0.828 † | (0.491) |

| ITA | −0.454 | (0.466) | −0.438 | (0.466) | −0.492 | (0.483) | −0.472 | (0.484) | −0.502 | (0.491) |

| JPN | −0.081 | (0.445) | −0.085 | (0.446) | −0.096 | (0.466) | −0.102 | (0.468) | −0.108 | (0.477) |

| KOR | −0.729 | (0.482) | −0.721 | (0.482) | −0.702 | (0.495) | −0.690 | (0.496) | −0.627 | (0.501) |

| LUX | −0.522 | (0.455) | −0.520 | (0.456) | −0.569 | (0.471) | −0.567 | (0.473) | −0.584 | (0.480) |

| NLD | −0.641 | (0.473) | −0.653 | (0.474) | −0.637 | (0.489) | −0.657 | (0.490) | −0.707 | (0.499) |

| POL | −2.599 *** | (0.642) | −2.593 *** | (0.641) | −2.576 *** | (0.629) | −2.570 *** | (0.627) | −2.624 *** | (0.632) |

| PRT | −1.174 * | (0.495) | −1.173 * | (0.495) | −1.228 * | (0.502) | −1.228 * | (0.503) | −1.265 * | (0.510) |

| SWE | −1.014 * | (0.486) | −1.018 * | (0.486) | −1.064 * | (0.496) | −1.069 * | (0.496) | −1.095 * | (0.504) |

| TUR | −1.451 ** | (0.525) | −1.452 ** | (0.524) | −1.506 ** | (0.526) | −1.508 ** | (0.526) | −1.559 ** | (0.532) |

| USA | 0.203 | (0.426) | 0.205 | (0.427) | 0.207 | (0.450) | 0.209 | (0.452) | 0.224 | (0.458) |

| Independent variables | ||||||||||

| CPI | −0.176 | (0.197) | −0.222 | (0.200) | 0.293 | (0.243) | ||||

| EGDI | 0.951 *** | (0.176) | 0.958 *** | (0.177) | 0.960 *** | (0.191) | ||||

| CPI × EGDI | −0.633 *** | (0.158) | ||||||||

| AIC | 825.26 | 826.46 | 790.78 | 791.54 | 775.39 | |||||

| Dependent Variable: Positive FDI Inflow or Not | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 2018 | Year 2017 | Year 2016 | Year 2015 | Year 2014 | Year 2014–2018 | |||||||

| Control variables | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | −35.62 ** | (12.06) | −30.66 * | (12.72) | −29.63 * | (13.54) | −16.07 | (26.66) | −20.50 | (24.80) | −34.42 *** | (5.061) |

| Log GDP | 1.240 ** | (0.440) | 1.197 ** | (0.460) | 1.204 * | (0.499) | 0.537 | (0.978) | 0.537 | (0.899) | 1.201 *** | (0.181) |

| TPG | 0.011 | (0.009) | −0.005 | (0.010) | 0.010 | (0.009) | −0.005 | (0.017) | −0.007 | (0.019) | 0.008 * | (0.004) |

| GPC | −0.000 | (0.000) | −0.000 | (0.000) | 0.000 | (0.000) | 0.000 | (0.000) | 0.000 | (0.000) | −0.000 | (0.000) |

| POLI | 1.636 | (1.247) | −1.772 | (1.231) | −2.895 ** | (1.043) | −2.611 ** | (0.937) | −3.994 ** | (1.384) | −0.456 | (0.316) |

| MOB | −0.043 * | (0.021) | −0.004 | (0.016) | −0.042 * | (0.017) | 0.002 | (0.019) | 0.028 | (0.026) | −0.003 | (0.007) |

| Partner country fixed effects | ||||||||||||

| BEL | −0.001 | (1.144) | −2.116 † | (1.256) | −2.175 † | (1.264) | −20.55 | (2145.) | −2.106 | (1.593) | −1.735 ** | (0.545) |

| CAN | −0.529 | (1.235) | −0.375 | (1.133) | −1.937 | (1.299) | −2.252 † | (1.343) | −0.791 | (1.297) | −1.003 * | (0.511) |

| CHE | 0.008 | (1.146) | −2.122 † | (1.254) | −1.405 | (1.187) | −3.624* | (1.566) | 0.039 | (1.176) | −1.095 * | (0.504) |

| CZE | −0.717 | (1.204) | −1.310 | (1.152) | −20.34 | (1276.) | −2.296 † | (1.327) | −2.114 | (1.589) | −1.949 *** | (0.557) |

| DNK | 0.652 | (1.127) | −1.276 | (1.161) | −3.161 * | (1.389) | −1.283 | (1.193) | 0.099 | (1.185) | −0.828 † | (0.491) |

| ITA | 0.214 | (1.178) | −0.265 | (1.121) | −1.972 | (1.297) | −0.388 | (1.116) | −0.744 | (1.305) | −0.502 | (0.491) |

| JPN | 1.040 | (1.147) | −0.159 | (1.100) | −0.919 | (1.194) | −0.976 | (1.200) | 0.295 | (1.186) | −0.108 | (0.477) |

| KOR | 0.454 | (1.161) | −0.874 | (1.168) | −2.387 † | (1.339) | −0.685 | (1.120) | 0.401 | (1.171) | −0.627 | (0.501) |

| LUX | 0.021 | (1.149) | −0.639 | (1.100) | −0.719 | (1.147) | −1.312 | (1.187) | −0.752 | (1.304) | −0.584 | (0.480) |

| NLD | 0.865 | (1.159) | −1.243 | (1.168) | −1.092 | (1.223) | −2.124 | (1.373) | −0.634 | (1.319) | −0.707 | (0.499) |

| POL | −1.681 | (1.392) | −2.074 | (1.267) | −3.168 * | (1.387) | −20.57 | (2166.) | −18.27 | (1346.) | −2.624 *** | (0.632) |

| PRT | −0.695 | (1.209) | −1.309 | (1.152) | −3.177 * | (1.383) | −1.332 | (1.181) | −0.816 | (1.291) | −1.265 * | (0.510) |

| SWE | 0.015 | (1.147) | −1.268 | (1.163) | −2.179 † | (1.262) | −2.260 † | (1.340) | −0.760 | (1.302) | −1.095 * | (0.504) |

| TUR | −0.715 | (1.204) | −1.290 | (1.158) | −2.174 † | (1.264) | −3.623 * | (1.567) | −2.097 | (1.596) | −1.559 ** | (0.532) |

| USA | 0.500 | (1.150) | −0.068 | (1.074) | −0.121 | (1.118) | −0.041 | (1.045) | 1.092 | (1.087) | 0.224 | (0.458) |

| Independent variables | ||||||||||||

| CPI | 0.494 | (2.069) | 1.728 | (1.173) | 1.465 † | (0.821) | 0.300 | (0.613) | 0.901 | (0.656) | 0.293 | (0.243) |

| EGDI | 3.712 ** | (1.292) | 1.290 † | (0.725) | 3.157 *** | (0.868) | 1.711 * | (0.756) | 1.533 † | (0.792) | 0.960 *** | (0.191) |

| CPI × EGDI | −1.385 | (1.622) | −1.405 * | (0.690) | −1.680 ** | (0.639) | −0.592 | (0.381) | −0.263 | (0.310) | −0.633 *** | (0.158) |

| AIC | 189.61 | 190.34 | 164.21 | 153.34 | 160.57 | 775.39 | ||||||

| Dependent Variable: Positive FDI Inflow or Not | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | ||||

| Control variables | ||||||

| Intercept | −34.07 *** | (5.084) | −33.65 *** | (5.110) | −34.42 *** | (5.061) |

| Log GDP | 1.190 *** | (0.182) | 1.177 *** | (0.183) | 1.200 *** | (0.182) |

| TPG | 0.008 * | (0.004) | 0.008 * | (0.004) | 0.008 * | (0.004) |

| GPC | −0.000 | (0.000) | 0.000 | (0.000) | −0.000 | (0.000) |

| POLI | −0.459 | (0.316) | −0.467 | (0.315) | −0.456 | (0.316) |

| MOB | −0.004 | (0.007) | −0.005 | (0.007) | −0.003 | (0.007) |

| Partner country fixed effects | ||||||

| BEL | −1.735 ** | (0.547) | −1.714 ** | (0.546) | −1.738 ** | (0.545) |

| CAN | −0.975 † | (0.513) | −0.931 † | (0.511) | −1.005 * | (0.512) |

| CHE | −1.074 * | (0.506) | −1.025 * | (0.505) | −1.098 * | (0.505) |

| CZE | −1.983 *** | (0.561) | −2.119 *** | (0.568) | −1.936 *** | (0.560) |

| DNK | −0.804 | (0.492) | −0.761 | (0.490) | −0.830 † | (0.492) |

| ITA | −0.443 | (0.492) | −0.609 | (0.501) | −0.470 | (0.503) |

| JPN | −0.110 | (0.479) | −0.121 | (0.477) | −0.107 | (0.478) |

| KOR | −0.588 | (0.501) | −0.703 | (0.506) | −0.604 | (0.507) |

| LUX | −0.562 | (0.481) | −0.524 | (0.479) | −0.586 | (0.481) |

| NLD | −0.673 | (0.501) | −0.637 | (0.498) | −0.706 | (0.499) |

| POL | −2.687 *** | (0.636) | −2.789 *** | (0.637) | −2.621 *** | (0.633) |

| PRT | −1.345 ** | (0.517) | −1.422 ** | (0.523) | −1.269 * | (0.511) |

| SWE | −1.072 * | (0.506) | −1.026 * | (0.505) | −1.097 * | (0.505) |

| TUR | −1.501 ** | (0.532) | −1.725 ** | (0.544) | −1.519 ** | (0.550) |

| USA | 0.221 | (0.460) | 0.210 | (0.458) | 0.225 | (0.458) |

| Independent variables | ||||||

| CPI | 0.276 | (0.244) | 0.266 | (0.243) | 0.293 | (0.243) |

| EGDI | 1.089 *** | (0.217) | 1.153 *** | (0.223) | 0.974 *** | (0.198) |

| CPI × EGDI | −0.686 *** | (0.162) | −0.848 *** | (0.199) | −0.622 *** | (0.163) |

| Dissimilarity in corruption level | ||||||

| Change of EGDI effect (when CPI difference > 20) | −0.312 | (0.239) | ||||

| Inferior dissimilarity in corruption level | ||||||

| Change of EGDI effect (when HostCPI < HomeCPI − 20) | −0.715 † | (0.395) | ||||

| Superior dissimilarity in corruption level | ||||||

| Change of EGDI effect (when HostCPI > HomeCPI + 20) | −0.094 | (0.341) | ||||

| p-value for EGDI effect difference | 0.192 | 0.070 † | 0.782 | |||

| AIC | 775.69 | 774.08 | 777.32 | |||

| Dependent Variable: Positive FDI Inflow or Not | ||

|---|---|---|

| Control variables | ||

| Intercept | −31.63 *** | (4.816) |

| Log GDP | 1.096 *** | (0.171) |

| TPG | 0.005 | (0.004) |

| GPC | 0.000 | (0.000) |

| POLI | −0.414 * | (0.207) |

| MOB | 0.000 | (0.006) |

| Partner country fixed effects | ||

| BEL | −4.398 * | (2.111) |

| CAN | −1.186 † | (0.623) |

| CHE | −3.538 * | (1.719) |

| CZE | −1.471 ** | (0.534) |

| DNK | −1.296 † | (0.694) |

| ITA | −0.826 | (0.589) |

| JPN | −0.169 | (0.454) |

| KOR | −7.058 ** | (2.634) |

| LUX | −3.177 * | (1.527) |

| NLD | −1.079 † | (0.631) |

| POL | −4.425 † | (2.316) |

| PRT | −1.856 * | (0.861) |

| SWE | −1.223 * | (0.616) |

| TUR | −5.135 * | (2.281) |

| USA | −0.017 | (0.464) |

| EGDI effect for each partner(home) country | ||

| AUT’s EGDI | 0.221 | (0.332) |

| BEL’s EGDI | 3.513 † | (2.062) |

| CAN’s EGDI | 0.827 | (0.577) |

| CHE’s EGDI | 3.361 * | (1.691) |

| CZE’s EGDI | −0.372 | (0.459) |

| DNK’s EGDI | 1.212 † | (0.679) |

| ITA’s EGDI | 0.994 † | (0.545) |

| JPN’s EGDI | 0.357 | (0.369) |

| KOR’s EGDI | 7.904 ** | (2.763) |

| LUX’s EGDI | 3.667 * | (1.534) |

| NLD’s EGDI | 1.155 † | (0.631) |

| POL’s EGDI | 2.608 | (2.314) |

| PRT’s EGDI | 1.353 | (0.855) |

| SWE’s EGDI | 0.736 | (0.579) |

| TUR’s EGDI | 4.449 * | (2.201) |

| USA’s EGDI | 0.788 * | (0.396) |

| AIC | 777.89 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, K.; An, J. Corruption as a Moderator in the Relationship between E-Government and Inward Foreign Direct Investment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4995. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094995

Kim K, An J. Corruption as a Moderator in the Relationship between E-Government and Inward Foreign Direct Investment. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):4995. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094995

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Keunwoo, and Jaehyung An. 2022. "Corruption as a Moderator in the Relationship between E-Government and Inward Foreign Direct Investment" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 4995. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094995

APA StyleKim, K., & An, J. (2022). Corruption as a Moderator in the Relationship between E-Government and Inward Foreign Direct Investment. Sustainability, 14(9), 4995. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094995