Understanding the Consumers of Entrepreneurial Education: Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation among Youths

Abstract

1. Introduction

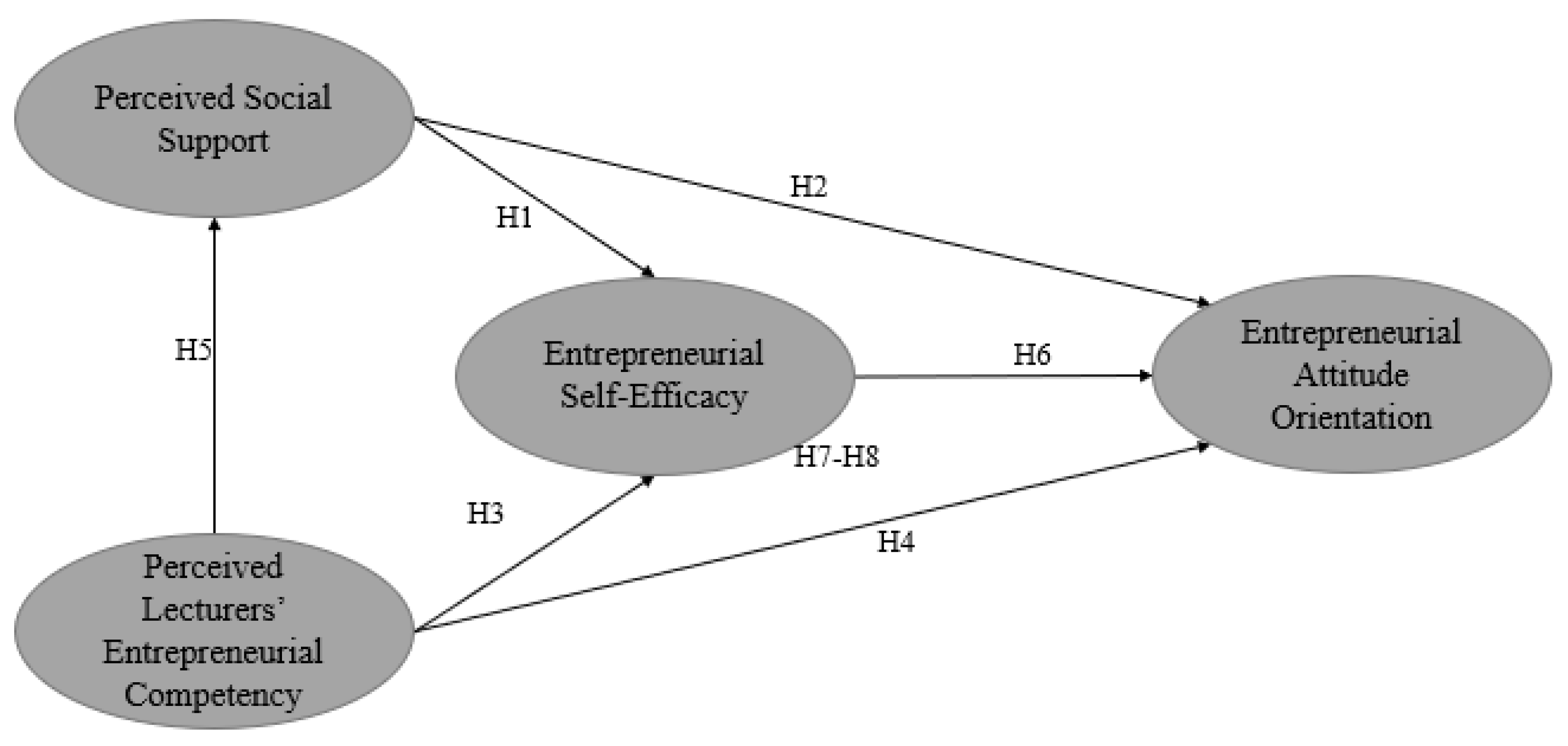

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

2.2. Perceived Social Support

2.3. Perceived Lecturers’ Entrepreneurial Competency

2.4. Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation

2.5. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy as Mediating Variable

3. Research Method

3.1. Instrument and Analysis

3.2. Respondents

4. Results

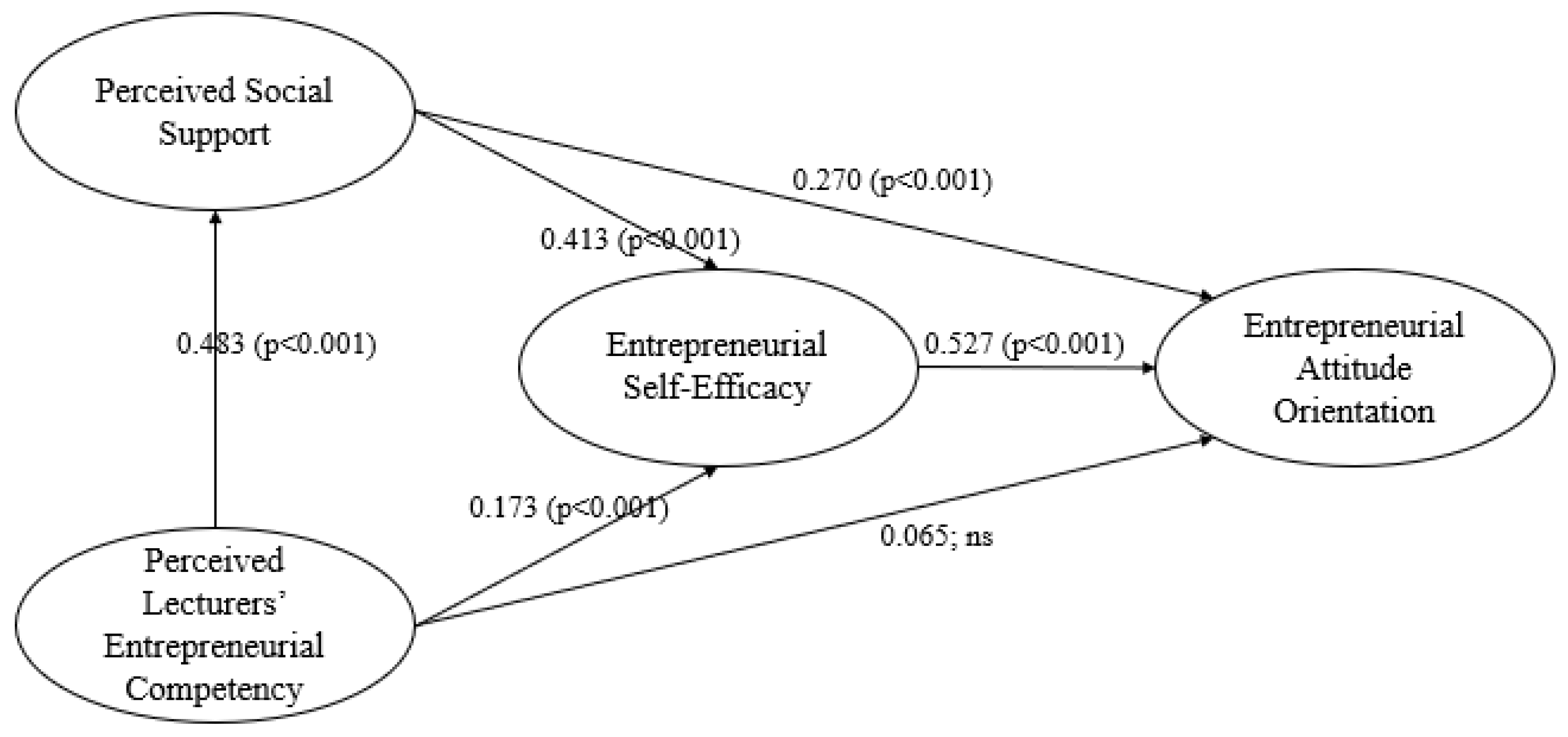

- X1 = 0.483 X2 (significant)

- X3 = 0.413 X1 (significant) + 0.173 X2 (significant)

- Y = 0.270 X1 (significant) + 0.065 X2 (non-significant) + 0.527 X3

- X1= Perceived Social Support

- X2 = Perceived Lecturers’ Entrepreneurial Competency

- X3 = Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

- Y = Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation

- The total effect of perceived social support on entrepreneurial attitude orientation:

- 0.270 + (0.413 × 0.527) = 0.487651

- The total effect of perceived lecturers’ entrepreneurial competency on entrepreneurial attitude orientation:

- (0.173 × 0.527) + (0.483 × 0.270) = 0.221581

- The total effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial attitude orientation: 0.527

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walter, S.; Block, J.H. Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardyan, E.; Wijaya, O.Y.A. Effect of the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education programs on entrepreneurial competency and business performance. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2018, 12, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, J.E.; Setiawan, J.L.; Sanjaya, E.L.; Wardhani, F.P.I.; Virlia, S.; Dewi, K.; Kasim, A. Developing a measurement instrument for high school students’ entrepreneurial orientation. Cogent Educ. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, J.L. Examining entrepreneurial social support among Undergraduates. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Organizational Innovation, Hua Hin, Thailand, 2–4 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wardana, L.W.; Narmaditya, B.S.; Wibowo, A.; Mahendra, A.; Wibowo, N.A.; Harwida, G.; Rohman, A.N. The impact of entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial mindset: The mediating role of attitude and self-efficacy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Duysters, G.; Cloodt, M. The role of entrepreneurship education as a predictor of university students’ entrepreneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2013, 10, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterbeek, H.; van Praag, M.; Ijsselstein, A. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship skills and motivation. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2010, 54, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubker, O.; Arroud, M.; Ouajdouni, A. Entrepreneurship education versus management students’ entrepreneurial intentions. A PLS-SEM approach. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azjen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behavior, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Meiden, A. Smallest space analysis of students’ attitudes on marketing education. Eur. J. Mark. 1977, 11, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, B.A.; Memon, M.; Shah, N. Attitudes towards entrepreneurship among the students of Thailand: An entrepreneurial attitude orientation approach. Educ. + Train. 2020, 63, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahbod, F.; Azadehdel, M.; Mofidi, M.K.; Shahabi, S.; Khoshamooz, H.; Pazhouh, L.D.; Ghorbaninejad, N.; Shadkam, F. The relationship between trait emotional intelligence and entrepreneurship attitudes and intentions. J. Public Adm. Policy Res. 2013, 5, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloulou, W.J. Predicting entrepreneurial intentions of freshmen students from EAO modeling and personal background: A Saudi perspective. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2016, 8, 180–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joensuu-Salo, S.; Viljamaa, A.; Varamäki, E. Do intentions ever die? The temporal stability of entrepreneurial intention and link to behavior. Educ. + Train. 2020, 62, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfud, T.; Triyono, M.B.; Sudira, P.; Mulyani, Y. The influence of social capital and entrepreneurial attitude orientation on entrepreneurial intentions: The mediating role of psychological capital. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 26, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamizharasi, G.; Panchanatham, N. An Empirical Study of Demographic Variables on Entrepreneurial Attitudes. Int. J. Trade, Econ. Finance 2010, 1, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Freeman, W.H.; Lightsey, R. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. J. Cogn. Psychother. 1999, 13, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadian, G.; Opie, T.R.; Parise, S. The influence of emotional carrying capacity and network ethnic diversity on entrepreneurial self-efficacy. N. Engl. J. Entrep. 2018, 21, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmieleski, K.; Corbett, A.C. The contrasting interaction effects of improvisational behavior with entrepreneurial self-efficacy on new venture performance and entrepreneur work satisfaction. J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Huang, J.-C.; Farh, J.-L. Employee Learning Orientation, Transformational Leadership, and Employee Creativity: The Mediating Role of Employee Creative Self-Efficacy. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy for Changing Society, 6th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, F.; Karadağ, H.; Tuncer, B. Big five personality traits, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1188–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y.; Chengang, Y.; Arbizu, A.D.; Haider, M.J. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: Do entrepreneurial creativity and education matter? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Obschonka, M.; Schwarz, S.; Cohen, M.; Nielsen, I. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.; Soomro, B.A.; Shah, N. Enablers of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in a developing country. Educ. Train. 2019, 61, 684–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, F.J.; Chamorro-Mera, A.; Rubio, S. Academic entrepreneurship in Spanish universities: An analysis of the determinants of entrepreneurial intention. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 23, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Caloen de Basseghem, C. The Mediating Effect of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy on The Relationship between Academic Grade and Entrepreneurial Intention. In Louvain School of Management; Université Catholique de Louvain: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Naushad, M.; Malik, S.A. The mediating effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in entrepreneurial intention – a study in Saudi Arabian context. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2018, 16, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ciuchta, M.P.; Finch, D. The mediating role of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions: Exploring boundary conditions. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2019, 11, e00128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Choi, D.S.; Sung, C.S. A Study on the Effect of Entrepreneurial Mentoring on Entrepreneurial Intention: Mediating Effects of Social Support and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Ventur. Entrep. 2020, 15, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, P.B.; Stimpson, D.V.; Huefner, J.C.; Hunt, H.K. An Attitude Approach to the Prediction of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1991, 15, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, L. Entrepreneurial attitude orientation versus entrepreneurial success among entrepreneurs in small and medium enterprise (SME). J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2019, 6, 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Adv. Behav. Res. Ther. 1978, 1, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Brazeal, D.V. Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schjoedt, L.; Craig, J.B. Development and validation of a unidimensional domain-specific entrepreneurial self-efficacy scale. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajkovic, A.D.; Luthans, F. Self-efficacy and work related performance. Psychological Bulletin 1998, 124, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.C.; Liguori, E.W. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions: Outcome expectations as mediator and subjective norms as moderator. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Noble, A.; Jung, D.; Ehrlich, S. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy: The Development of a Measure and Its Relationship to Entrepreneurial Action; Babson College: Wellesley, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.C.; Greene, P.G.; Crick, A. Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumaker, S.A.; Brownell, A. Toward a Theory of Social Support: Closing Conceptual Gaps. J. Soc. Issues 1984, 40, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, J.L. Examining Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy among Students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 115, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, J.C.; Sequeira, J.M. Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: A Theory of Planned Behavior approach. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, C.P.H.; Bowsher, J.; Maloney, J.P.; Lillis, P.P. Social support: A conceptual analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 25, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atri, A.; Sharma, M. Designing a Mental Health Education Program for South Asian International Students in United States. Calif. J. Health Promot. 2006, 4, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pruett, M.; Shinnar, R.S.; Toney, B.; Llopis, F.; Fox, J. Explaining entrepreneurial intentions of university students: A cross-cultural study. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2009, 15, 571–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajalli, P.; Sobhi, A.; Ganbaripanah, A. The relationship between daily hassles and social support on mental health of university students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 5, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Salam, M.; ur Rehman, S.; Fayolle, A.; Jaafar, N.; Ayupp, K. Impact of support from social network on entrepreneurial intention of fresh business graduates: A structural equation modeling approach. Educ. Train. 2018, 60, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Song, Y.; Pan, B. How University Entrepreneurship Support Affects College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions: An Empirical Analysis from China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 63224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeem, A.A.; Asimiran, S. Factors affecting entrepreneurial self-efficacy of engineering students. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2016, 6, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazumi, T.; Kawai, N. Institutional support and women’s entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2017, 11, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, L.J.; Audu, A.; Karatu, B.A. Emotional intelligence and social support as determinants of entrepreneurial success among business owners in onitsha metropolis, nigeria. Eur. J. Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 5, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadmiko, P. Linking perceived social support to social entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of attitude becoming social entrepreneur. J. Menara Èkon. Penelit. Dan Kaji. Ilm. Bid. Èkon. 2020, 6, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanapi, Z.; Nordin, M.S. Unemployment among malaysia graduates: Graduates’ attributes, lecturers’ competency and quality of education. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 112, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BarNir, A.; Watson, W.E.; Hutchins, H. Mediation and Moderated Mediation in the Relationship Among Role Models, Self-Efficacy, Entrepreneurial Career Intention, and Gender. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 270–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaViolette, E.M.; Lefebvre, M.R.; Brunel, O. The impact of story bound entrepreneurial role models on self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2012, 18, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malebana, M.J. The effect of entrepreneurial role models on entrepreneurial intention in South Africa. J. Contemp. Manag. 2006, 17, 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, I.; Yeld, N.; Hendry, J. Higher Education Monitor: A Case for Improving Teaching and Learning in South African Higher Education; Council on Higher Education: Pretoria, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, G.N.; Jansen, E. The founder’s self-assessed competence and venture performance. J. Bus. Ventur. 1992, 7, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, E.; Mosey, S.; Wright, M. The influence of university departments on the evolution of entrepreneurial competencies in spin-off ventures. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, T.W.; Lau, T.; Chan, K. The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises: A conceptualization with focus on entrepreneurial competencies. J. Bus. Ventur. 2002, 17, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchelmore, S.; Rowley, J. Entrepreneurial competencies: A literature review and development agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayton, J.C.; Kelley, D.J. A competency-based framework for promoting corporate entrepreneurship. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 45, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldureanu, G.; Ionescu, A.M.; Bercu, A.-M.; Bedrule-Grigoruță, M.V.; Boldureanu, D. Entrepreneurship Education through Successful Entrepreneurial Models in Higher Education Institutions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 31267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellhofer, K.; Puulmalainen, K. Can role models boost entrepreneurial attitudes? Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 274–290. [Google Scholar]

- Baluku, M.M.; Onderi, P.; Otto, K. Predicting self-employment intentions and entry in Germany and East Africa: An investigation of the impact of mentoring, entrepreneurial attitudes, and psychological capital. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2019, 33, 289–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulida, E.; Doriza, S.; Refai, D.; Argarini, F. The Influence of Entrepreneurial Role Model on Entrepreneurial Attitude in Higher Education Student. KnE Soc. Sci. 2020, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesper, K.; McMullan, W. Entrepreneurship: Today courses, tomorrow degrees? Entrep. Theory Pract. 1988, 13, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hytti, U.; O’Gorman, C. What is “enterprise education”? An analysis of the objectives and methods of enterprise education programmes in four European countries. Educ. Train. 2004, 46, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Jean, E.; Audet, J. Factors leading to satisfaction in amentoring scheme for novice entrepreneurs. Int. J. Evid. Based Coach. Mentor. 2009, 7, 148–161. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, P.; Brady, B. A Guide to Youth Mentoring: Providing Effective Social Support; Jesicca Kingsley Publisher: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Azjen, I. On Behaving in Accordance with One’s Attitudes. In Consistency in Social Behavior: The Ontario Symposium 2; Zanna, M.P., Higgins, E.T., Herman, C.P., Eds.; Erlabaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Azjen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, P.B. Prediction of Entrepreneurship Based on an Attitude Consistency Model; Brigham Young University: Provo, UT, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.-L.; Long, W.A.; Robinson, P. Entrepreneurship attitude orientation and the intention to start a business. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 1996, 13, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ede, F.O.; Panigrahi, B.; Calcich, S.E. African American Students’ Attitudes Toward Entrepreneurship Education. J. Educ. Bus. 1998, 73, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.L.; Gibson, S.G. Examining the entrepreneurial attitudes of US business students. Educ. Train. 2008, 50, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isma, A.; Sudarmiatin, S.; Hermawan, A. The effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, subjective norm, and locus of control on entrepreneurial intention through entrepreneurial attitude in economic faculty students of universitas negeri makassar. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Law 2020, 23, 262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Firmansyah, A.H.; Djatmika, E.T. The effect of adversity quotient and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intention through entrepreneurial attitude. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 18, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Shao-hui, L.; Ping, L.; Peng-Peng, F. Mediation and Moderated Mediation in The Relationship among Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, Entrepreneurial Intention, Entrepreneurial Attitude and Role Models. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Management Science & Engineering (18th), Rome, Italy, 13–15 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Esnard-Flavius, T. Gender, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, And Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientations: The Case Of The Caribbean. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. (IBER) 2010, 9, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenech, R.; Baguant, P.; Ivanov, D. Entrepreneurial attitudes, self-efficacy, and subjective norms amongst female Emirati entrepreneurs. Int. J. Entrep. 2019, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Exercise of Personal and Collective Efficacy in Changing Societies. In Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies; Bandura, A., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kickul, J.; D’Intino, R.S. Measure for measure: Modeling entrepreneurial self-efficacy onto instrumental tasks within the new venture creation process. N. Engl. J. Entrep. 2005, 8, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. On the Functional Properties of Perceived Self-Efficacy Revisited. J. Manag. 2011, 38, 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihie, Z.A.L.; Begheri, A. Self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: The mediation effect of self-regulation. Vocat. Learn. 2013, 6, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, A. Hubungan Dukungan Sosial Dengan Kepercayaan Diri Pada Siswa di SMA Amir Hamzah Medan. In Psikologi; Universitas Medan Area: Medan, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, A.M.; Ashforth, B.E. A Longitudinal investigation of the relationships between job information sources, applicant perceptions of fit, and work outcomes. Pers. Psychol. 1997, 50, 395–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.K.; Burmeister-Lamp, K.; Simmons, S.A.; Foo, M.D.; Hong, M.C.; Pipes, J.D. “I know I can, but I don’t fit”: Perceived fit, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, L.M.; Spencer, S.M. Competence at Work: Models for Superior Performance; John Wiley & Son: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, G.D.; Walker, R.R. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: A confirmation study. J. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 47, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonsing, K.; Zimet, G.; Tse, S.S.-K. Assessing social support among South Asians: The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Asian J. Psychiatry 2012, 5, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, M.L.; Cooper, L. Social Support Measures Review; National Center for Latino Child and Family Research: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011.

- Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Surviva; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientist and Practitioner-Researchers; Blackwell Publishers Ltd: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, N.G.; Vozikis, G.S. The Influence of Self-Efficacy on the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions and Actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Qian, S.; Ma, D. The Relationship between Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Firm Performance: A Meta-Analysis of Main and Moderator Effects. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 55, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, T.L.; Adelman, M.B. Communicating Social Support; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Pihie, Z.L.; Bagheri, A. Malay Secondary School Students’ Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation and Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy: A Descriptive Study. J. Appl. Sci. 2011, 11, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratkovič, T.; Antončič, B.; DeNoble, A.F. Relationships between networking, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and firm growth: The case of Slovenin companies. Ekon. Istraz. 2016, 25, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kumar, R.; Shukla, S. Creativity, Proactive Personality and Entrepreneurial Intentions: Examining the Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2019, 23, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Murad, M.; Shahzad, F.; Khan, M.A.S.; Ashraf, S.F.; Dogbe, C.S.K. Entrepreneurial Passion to Entrepreneurial Behavior: Role of Entrepreneurial Alertness, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Proactive Personality. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naktiyok, A.; Karabey, C.N.; Gulluce, A.C. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: The Turkish case. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2009, 6, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisubi, M.K.; Korir, M. Entrepreneurial Training and Entrepreneurial Intentions. Seisense J. Manag. 2021, 4, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Jean, É.; Mathieu, C. Developing attitudes toward an entrepreneurial career through mentoring: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. J. Career Dev. 2015, 42, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaho, E.; Olomi, D.R.; Urassa, C.C. Students’ entrepreneurial selfefficacy: Does the teaching method matter? Educ. Train. 2015, 57, 908–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaho, E. Entrepreneurial curriculum as an antecedent to entrepreneurial values in Uganda: A SEM model. Glob. Adv. Res. J. Manag. Bus. Stud. 2013, 2, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.02 | 1.34 | (0.797) | |||

| 7.17 | 1.29 | 0.483 ** | (0.949) | ||

| 7.24 | 1.01 | 0.497 ** | 0.373 ** | (0.931) | |

| 7.44 | 0.94 | 0.563 ** | 0.392 ** | 0.685 ** | (0.901) |

| Outcome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation | Perceived Social Support | Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy | ||||

| Predictor | Direct | Indirect | Direct | Indirect | Direct | Indirect |

| Perceived social support (ESS) | 0.270 *** | 0.218 ** | - | - | 0.413 *** | - |

| Perceived lecturers’ entrepreneurial competency (LEC) | 0.065 ns | 0.09 ** | 0.483 *** | - | 0.173 *** | 0.199 *** |

| Entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) | 0.527 *** | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Setiawan, J.L.; Kasim, A.; Ardyan, E. Understanding the Consumers of Entrepreneurial Education: Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation among Youths. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084790

Setiawan JL, Kasim A, Ardyan E. Understanding the Consumers of Entrepreneurial Education: Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation among Youths. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084790

Chicago/Turabian StyleSetiawan, Jenny Lukito, Azilah Kasim, and Elia Ardyan. 2022. "Understanding the Consumers of Entrepreneurial Education: Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation among Youths" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084790

APA StyleSetiawan, J. L., Kasim, A., & Ardyan, E. (2022). Understanding the Consumers of Entrepreneurial Education: Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Attitude Orientation among Youths. Sustainability, 14(8), 4790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084790