What Factors Influence Customer Attitudes and Mindsets towards the Use of Services and Products of Islamic Banks in Bangladesh?

Abstract

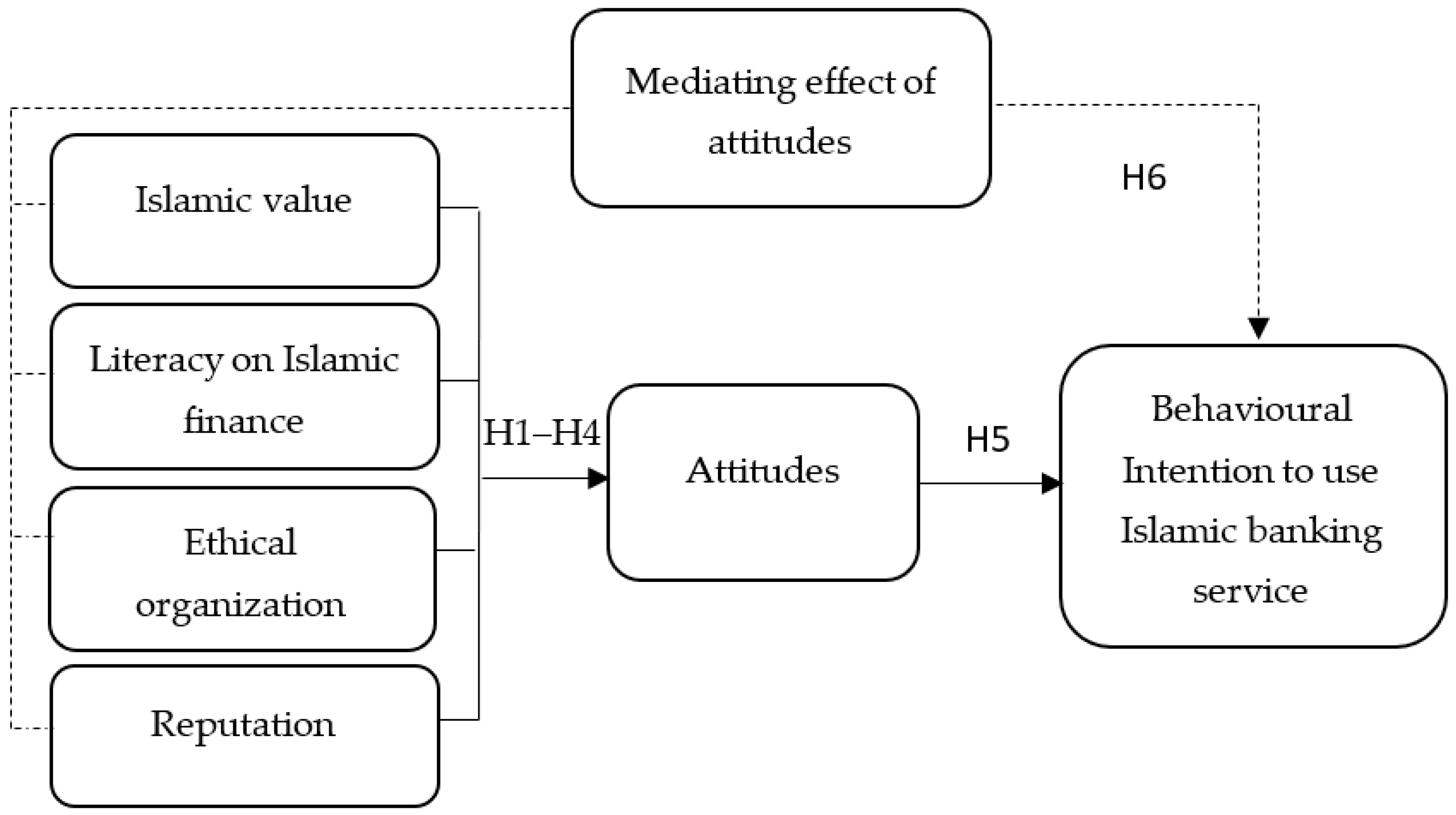

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Underpinning Theory

2.2. Literacy on Islamic Finance

2.3. Ethical Organisation

2.4. Islamic Values

2.5. Reputation

2.6. Attitudes

2.7. Mediating Effect of Attitude

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Instruments

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

3.3. Common Method Bias

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Information

4.2. Assessment of the Measurement Model

4.3. Assessment of the Structural Model

4.4. Importance-Performance Matrix Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Theoretical and Practical Contribution

7. Limitation and Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jalil, A.; Rahman, M.K. Financial transactions in Islamic Banking are viable alternatives to the conventional banking transactions. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2010, 1, 219–223. [Google Scholar]

- Mindra, R.; Bananuka, J.; Kaawaase, T.; Namaganda, R.; Teko, J. Attitude and Islamic banking adoption: Moderating effects of pricing of conventional bank products and social influence. J. Islamic Account. Bus. Res. 2022, 13, 534–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. Political transition and bank performance: How important was the Arab Spring? J. Comp. Econ. 2016, 44, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.; Nehmeh, N.; Sioufi, I. Assessing the effect of organisational commitment on turnover intentions amongst Islamic bank employees. ISRA Int. J. Islamic Financ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. Arab government responses to Islamic finance: The cases of Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Mediterr. Politics 2002, 7, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, P.C.; Nkamnebe, A.D. Islamic bank selection criteria in Nigeria: A model development. J. Islamic Mark. 2019, 11, 1837–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, N.A.; Muwazir, M.R. Islamic banking selection criteria: A multi-ethnic perspective. J. Islamic Mark. 2020, 12, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusuki, A.W.; Abdullah, N.I. Why do Malaysian customers patronise Islamic banks? Int. J. Bank Mark. 2007, 25, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saleh, M.A.; Quazi, A.; Keating, B.; Gaur, S.S. Quality and image of banking services: A comparative study of conventional and Islamic banks. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, R.; Alwi, S. Explicating consumer segmentation and brand positioning in the Islamic financial services industry: A Malaysian perspective. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2015, 7, 253–274. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, W.; Ben Jedidia, K.; Majdoub, J. How Ethical is I slamic Banking in the Light of the Objectives of I slamic Law? J. Relig. Ethics 2015, 43, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M.A. Bayesian analysis of attribution processes. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 82, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Jaccard, J.; Davidson, A.R.; Ajzen, I.; Loken, B. Predicting and understanding family planning behaviors. In Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Nature and operation of attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Rahman, M.K.; Issa Gazi, M.A.; Rahaman, M.A.; Hossain, M.M.; Akter, S. Analyzing of User Attitudes Toward Intention to Use social media for Learning. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211060784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugandini, D.; Effendi, M.I.; Darasta, B.Y. Intention To Use: Study Online Shopping Based On Android Applications. Proc. Eng. 2020, 2, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nursalwani, M.; Zulariff, A.L. The effect of attitude, subjective norm and perceived behaviour control towards intention of Muslim youth at public universities in Kelantan to consume halal labelled chocolate bar product. Can. Soc. Sci. 2017, 13, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, H.; Rahman, A.R.A.; Razak, D.A.; Rizal, H. Consumer attitude and preference in the Islamic mortgage sector: A study of Malaysian consumers. Manag. Res. Rev. 2017, 40, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husin, M.M.; Ab Rahman, A. Predicting intention to participate in family takaful scheme using decomposed theory of planned behaviour. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2016, 43, 1351–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.A.A.; Ramlan, W.K.; Karim, M.A.; Osman, Z. The effects of social influence and financial literacy on savings behavior: A study on students of higher learning institutions in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Losada, R.; Montero-Navarro, A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, J.L.; González-Torres, T. Retirement planning and financial literacy, at the crossroads. A bibliometric analysis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 44, 102109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, S.H.A.; Rashid, R.A.; Hamed, A.B. Islamic financial literacy and its determinants among university students: An exploratory factor analysis. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2016, 6, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, M.N.; Abdullah, M.F. The World’s Oldest University and Its Financing Experience: A Study On Al-Qarawiyyin University (859-990). J. Nusant. Stud. (JONUS) 2021, 6, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antara, P.M.; Musa, R.; Hassan, F. Bridging Islamic financial literacy and halal literacy: The way forward in halal ecosystem. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choudhury, M.A.; Hoque, M.N. Shari’ah and economics: A generalized system approach. Int. J. Law Manag. 2017, 59, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struckell, E.M.; Patel, P.C.; Ojha, D.; Oghazi, P. Financial literacy and self-employment–The moderating effect of gender and race. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, K.; Kumar, S. Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 80–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, Y.; Çetin, M.; Bulut, M.; Jahangir, R. Islamic financial literacy scale: An amendment in the sphere of contemporary financial literacy. ISRA Int. J. Islamic Financ. 2021, 13, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, R.K.; Yahya, S.B.; Kassim, S. Impact of religiosity and branding on SMEs performance: Does financial literacy play a role? J. Islamic Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, M.A.; Rahman, M.K. The impact of Islamic branding on consumer preference towards Islamic banking services: An empirical investigation in Malaysia. J. Islamic Bank. Financ. 2014, 2, 209–229. [Google Scholar]

- Saygılı, M.; Durmuşkaya, S.; Sütütemiz, N.; Ersoy, A.Y. Determining intention to choose Islamic financial products using the attitude–social influence–self-efficacy (ASE) model: The case of Turkey. Int. J. Islamic Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, J.; Hill, R.P.; Martin, D. Corporate social responsibility in the 21st century: A view from the world’s most successful firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 48, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, T.; Nasuka, M.; Hidayat, A. Salesperson ethics behavior as antecedent of Islamic banking customer loyalty. J. Islamic Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, K.; Das, P.; Kammowanee, R.; Saluja, D.; Mitra, P.; Das, S.; Franzen, S. Ethical considerations of phone-based interviews from three studies of COVID-19 impact in Bihar, India. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e005981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwi, Z.; Parmitasari, R.D.A.; Syariati, A. An assessment on Islamic banking ethics through some salient points in the prophetic tradition. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohibien, G.P.D.; Laome, L.; Choiruddin, A.; Kuswanto, H. COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Return on Asset and Financing of Islamic Commercial Banks: Evidence from Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zusman, P. Participants’ Ethical Attitudes and Organizational Structure and Performance: Application to the Cooperative Enterprise. In Agricultural Cooperatives in Transition; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.J.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, T.H. The power of ethical leadership”: The influence of corporate social responsibility on creativity, the mediating function of psychological safety, and the moderating role of ethical leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.N.; Said, J.; Abdullah, M.F.; Ahmad, A.U.F. Money laundering from maqāṣid al Sharīʿah perspective with a particular reference to preservation of wealth (Hifz al-māl). J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2021, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hegazy, I.A. An Empirical Comparative Study Between Islamic And Commercial Banks’selection Criteria In Egypt. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 1995, 5, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzadjal, M.A.J.; Abu-Hussin, M.F.; Husin, M.M.; Hussin, M.Y.M. Moderating the role of religiosity on potential customer intention to deal with Islamic banks in Oman. J. Islamic Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunardi, A.; Herwany, A.; Febrian, E.; Anwar, M. Research on Islamic corporate social responsibility and Islamic bank disclosures. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2021, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muflih, M. The link between corporate social responsibility and customer loyalty: Empirical evidence from the Islamic banking industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhajjar, S. An Investigation of Consumers’ Negative Attitudes Towards Banks. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2022, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam, S.Z.; Ahmad, A.; Aslam, N.; Farooq, S. Reputation and cost benefits for attitude and adoption intention among potential customers using theory of planned behavior: An empirical evidence from Pakistan. J. Islamic Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, H.M.; Bukhari, K.S. Customer’s criteria for selecting an Islamic bank: Evidence from Pakistan. J. Islamic Mark. 2011, 2, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.N. Financing Heis Through Waqf Fund In Bangladesh: Issues And Possibilities. Int. J. Account. Financ. Rev. 2020, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamat, Z.; Abdul-Kadir, H. Attitude and patronage factors of bank customers in Malaysia: Muslim and non-Muslim views. Aust. Mark. J. 2012, 113, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, J.; Hussain, I.; Hussain, S.; Akram, S.; Shaheen, I.; Niu, B. The impact of knowledge sharing and innovation on sustainable performance in Islamic banks: A mediation analysis through a SEM approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Georgiadou, E.; Nickerson, C. Marketing strategies in communicating CSR in the Muslim market of the United Arab Emirates: Insights from the banking sector. J. Islamic Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaidi, J. The awareness and attitude of Muslim consumer preference: The role of religiosity. J. Islamic Account. Bus. Res. 2021, 12, 919–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, L.R.; Bilal, K.; Aziz, S.; Gul, A.; Shabbir, M.S.; Zamir, A.; Abro, H. A comparison of conventional versus Islamic banking customers attitudes and judgment. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.; Rahman, A.R.A.; Sondoh, S.L.; Hwa, A.M.C. Determinants of customers’ intention to use Islamic personal financing: The case of Malaysian Islamic banks. J. Islamic Account. Bus. Res. 2011, 2, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, S.; Fitriani, N. Brand religiosity aura and brand loyalty in Indonesia Islamic banking. J. Islamic Mark. 2017, 8, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Yesmin, M.; Jahan, N.; Kim, M. Effects of Service Justice, Quality, Social Influence and Corporate Image on Service Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty: Moderating Effect of Bank Ownership. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Gan, C.; Sarah, I.S.; Setiawan, S. Loyalty towards Islamic banking: Service quality, emotional or religious driven? J. Islamic Mark. 2019, 11, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.M.W.J.J.S. Religiosity and banking selection criteria among Malays in Lembah Klang. J. Syariah Jil 2008, 16, 99–130. [Google Scholar]

- Vitell, S.J.; Paolillo, J.G. Consumer ethics: The role of religiosity. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 46, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, M. Attitudes of Muslims towards Islamic banks in a dual-banking system. Am. J. Islamic Financ. 1996, 6, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sultan, W. Financial Characteristics of Interest-Free Banks and Conventional Banks; University of Wollongong: Wollongong, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Youssef, M.M.H.; Kortam, W.; Abou-Aish, E.; El-Bassiouny, N. Effects of religiosity on consumer attitudes toward Islamic banking in Egypt. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 786–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, N.; Rani, M. Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions toward Islamic banks: The influence of religiosity. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.H.; Lin, S.J.; Tang, D.P.; Hsiao, Y.J. The relationship between financial disputes and financial literacy. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2016, 36, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, M.K.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, K.H. Univariate and multivariate skewness and kurtosis for measuring nonnormality: Prevalence, influence and estimation. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 1716–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlan, D.; Ratan, A.L.; Zinman, J. Savings by and for the Poor: A Research Review and Agenda. Rev. Income Wealth 2014, 60, 36–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sheridan, J.; Coakes, C.O. SPSS: Analysis without Anguish; Version 18; John Wiley and Son: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Najmudin, M.; Haryono, T.; Ishak, A.; Hidayat, A.; Haryono, S. Integrating Attitudes to Sharia Banks in a Customer Loyalty Model of Sharia Banks: An Evidence from Indonesia. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 11, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, V. The effects of attitude, trust and switching cost on loyalty in commercial banks in Ho Minh City. Accounting 2020, 6, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.M.; Aftab, M. Incorporating attitude towards Halal banking in an integrated service quality, satisfaction, trust and loyalty model in online Islamic banking context. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2013, 1, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, A.A.; Suryani, T. Measuring the effects of service quality by using CARTER model towards customer satisfaction, trust and loyalty in Indonesian Islamic banking. J. Islamic Mark. 2019, 10, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kartika, T.; Firdaus, A.; Najib, M. Contrasting the drivers of customer loyalty; financing and depositor customer, single and dual customer, in Indonesian Islamic bank. J. Islamic Mark. 2019, 11, 933–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, N.; Abdullah, N.A. The effect of perceived service quality dimensions on customer satisfaction, trust, and loyalty in e-commerce settings: A cross cultural analysis. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2010, 22, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishada, Z.M.E.; Wahab, N.A. Factors affecting customer loyalty in Islamic banking: Evidence from Malaysian banks. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 264–273. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.; Cui, G.; Chung, Y.; Li, C. A multi-facet item response theory approach to improve customer satisfaction using online product ratings. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, R.; Akhmad, S.; Machmud, M. Effects of service quality, customer trust and customer religious commitment on customers satisfaction and loyalty of Islamic banks in East Java. Al-Iqtishad: J. Ilmu Ekon. Syariah 2015, 7, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bangladesh Bank. Developments of Islamic Banking in Bangladesh. 2020. Available online: https://www.bb.org.bd/pub/quaterly/islamic_banking/oct-dec2020.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Rahman, M.M.; Chowdhury, M.A.F.; Haque, M.M.; Rashid, M. Middle-income customers and their perception of Islamic banking in Sylhet: One of Bangladesh’s most pious cities. Int. J. Islamic Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2020, 14, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair Jr, J.F.; Cheah, J.H.; Becker, J.M.; Ringle, C.M. How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas. Mark. J. (AMJ) 2019, 27, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Gain more insight from your PLS-SEM results: The importance-performance map analysis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1865–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed, a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; & Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 26, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kaakeh, A.; Hassan, M.K.; Almazor, S.F.V.H. Factors affecting customers’ attitude towards Islamic banking in UAE. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2019, 11, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Souiden, N.; Jabeur, Y. The impact of Islamic beliefs on consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions of life insurance. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslichah, I.; Sanusi, S. The effect of religiosity and financial literacy on intention to use Islamic banking products. Asian J. Islamic Manag. 2020, 1, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Haron, S. Perceptions of Malaysian corporate customers towards Islamic banking products and services. Int. J. Islamic Financ. Serv. 2002, 3, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yousef, D.A. Islamic work ethic–A moderator between organizational commitment and job satisfaction in a cross-cultural context. Pers. Rev. 2001, 30, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheitani, A.; Imani, S.; Seyyedamiri, N.; Foroudi, P. Mediating effect of intrinsic motivation on the relationship between Islamic work ethic, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in banking sector. Int. J. Islamic Middle East. Financ. Manag. 2019, 12, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, A.J.; Al-Kazemi, A.A. Islamic work ethic in Kuwait. Cross cultural management: Int. J. 2007, 14, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manan, S.K.; Kamaluddin, N.; Puteh Salin, A.S.A. Islamic work ethics and organizational commitment: Evidence from employees of banking institutions in Malaysia. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2013, 21, 1471–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Bin Salahudin, S.N.; Binti Baharuddin, S.S.; Abdullah, M.S.; Osman, A. The effect of Islamic work ethics on organizational commitment. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 35, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamid, A.; Masood, O. Selection criteria for Islamic home financing: A case study of Pakistan. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2011, 3, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffar, M.A.; Musa, R. Determinants of attitude and intention towards Islamic financing adoption among non-users. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lajuni, N.; Wong, W.P.M.; Yacob, Y.; Ting, H.; Jausin, A. Intention to use Islamic banking products and its determinants. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2017, 7, 329–333. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | % | Characteristics | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Age | ||

| Man | 75.3 | 20–30 years | 56.3 |

| Women | 24.7 | 31–40 | 26.1 |

| Marital status | 41–50 | 14.3 | |

| Married | 50.8 | Above 50 | 3.3 |

| Unmarried | 48.6 | Income level | |

| Other | 0.6 | Below BDT 10000 | 23.1 |

| Educational Qualification | BDT 10001–20000 | 27.8 | |

| Bachelor’s | 40.4 | BDT 20001–30000 | 21.6 |

| Below secondary | 1.8 | BDT 30001–40000 | 9.4 |

| Secondary | 5.5 | BDT 40001–50000 | 7.6 |

| Higher secondary | 12.7 | Above BDT 50000 | 10.6 |

| Master’s | 38.0 | Occupation | |

| Ph.D. | 1.6 | Government service | 0.2 |

| Deal with bank | Self-employed | 6.3 | |

| Al-Arafah Islami bank | 22.7 | Private service | 65.9 |

| Exim Bank | 9.4 | Student | 24.3 |

| Islamic Bank | 68.0 | Others | 3.3 |

| Characteristics | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [FL1] Islamic financial bodies and institutions that offer Islamic financing which is based on Islamic law. | 3.06 | 1.239 | −1.167 | 0.247 |

| [FL2] Islamic financing is free from interest. | 3.04 | 1.194 | −1.128 | 0.322 |

| [FL3] To buy shares on a short-term basis, up and down of price is not speculation | 3.74 | 1.188 | −0.634 | −0.397 |

| [FL4] Preserving assets is one of Islamic finance principles. | 4.26 | 1.072 | −1.491 | 1.566 |

| [FL5] Selling of a commodity is permitted in Islam before it fully comes under our control. | 3.09 | 1.521 | −0.100 | −1.423 |

| [FL6] Islamic banks provides lease banking (Ijarah) | 3.96 | 1.123 | −0.864 | 0.404 |

| [FL7] In Ijara, the wealth usually does not go back to the owner. | 3.48 | 1.284 | −0.447 | −0.767 |

| [FL8] Based on profit-loss sharing principle (Musharakah), Islamic banks provide money. | 3.97 | 1.247 | −1.009 | −0.068 |

| [FL9] Based on profit-loss sharing principle (Mudarabah), Islamic banks might invest you. | 4.11 | 1.089 | −1.107 | 0.475 |

| [FL10] Qardul Hassanah or benevolent loans might be provided by Islamic banks. | 4.11 | 1.090 | −1.090 | 0.432 |

| [FL11] Trade banking methods or Murabahah is provided by Islamic banks. | 4.15 | 1.097 | −1.225 | 0.750 |

| [FL12] Borrowers are those who purchase goods in an Islamic finance trade credit management system or Murabahah. | 4.00 | 1.160 | −0.908 | −0.112 |

| [FL13] Industrial banking service (Istisna) is offered by Islamic banks. | 4.13 | 1.056 | −1.162 | 0.783 |

| [IV1] Islamic financial bodies and institutions that offer Islamic financing which is based on Islamic law. | 4.03 | 1.112 | −1.002 | 0.232 |

| [IV2] Muslims are not allowed to be connected with any kind of interest as provided by conventional institutions. | 4.23 | 1.108 | −1.435 | 1.270 |

| [IV3] Religious obligation motivates me to go for Islamic financing. | 4.01 | 1.173 | −1.004 | 0.100 |

| [IV4] Being a Muslim, I must use Islamic financing. | 4.09 | 1.124 | −1.019 | 0.083 |

| [EO1] Islamic banks are not involved in unethical activities. | 4.17 | 1.089 | −1.213 | 0.685 |

| [EO2] Islamic bank does not invest in unlawful activities. | 4.44 | 1.028 | −1.451 | 1.088 |

| [EO3] Islamic banks are an ethical organisation. | 4.00 | 1.195 | −0.975 | −0.030 |

| [EO4] I do love to take ethical banking services. | 3.55 | 1.116 | −0.836 | −0.106 |

| [EO5] In Islamic banks, equal treatment is provided to each and every customer. | 3.86 | 1.149 | −0.709 | −0.408 |

| [EO6] I can trust Islamic banks. | 4.21 | 1.073 | −1.380 | 1.258 |

| [RT1] Islamic financial bodies and institutions are concerned to uplift the image and reputation of Islam through their actions. | 4.06 | 1.081 | −0.939 | 0.082 |

| [RT2] Islamic financial bodies and institutions are greatly concerned to serve for the welfare of society through charity works, scholarships, donations, etc. | 4.10 | 1.084 | −1.120 | 0.506 |

| [RT3] Islamic financial bodies and institutions are greatly concerned not only maximizing profits, rather they are concerned to upgrade the living standard of the people and to serve for the welfare of society. | 4.07 | 1.086 | −1.019 | 0.289 |

| [ATT1] Choosing the services of Islamic banks is a good idea. | 4.21 | 1.033 | −1.202 | 0.649 |

| [ATT2] I do like to choose services provided by Islamic banks. | 4.22 | 1.064 | −1.304 | 0.983 |

| [ATT3] Most of the people in my surrounding are taking services and products of Islamic banks. | 4.07 | 1.123 | −1.072 | 0.242 |

| [ATT4] All the members in my family prefer to use the services of Islamic banks. | 4.19 | 1.068 | −1.194 | 0.627 |

| [ATT5] Most of my friends think to choose services of Islamic banks. | 4.15 | 1.063 | −1.132 | 0.540 |

| [INT1] In future, I am inclined to receive services and products of Islamic banks (Halal). | 4.21 | 1.065 | −1.323 | 1.113 |

| [INT2] I shall consider services of Islamic banks (Halal). | 4.23 | 1.045 | −1.377 | 1.331 |

| [INT3] I feel interested in receiving Islamic banking services. | 4.28 | 1.015 | −1.499 | 1.757 |

| [INT4] I feel interested in using Islamic banking products in future. | 4.26 | 1.044 | −1.482 | 1.615 |

| [INT5] I love to go for services Islamic banks. | 4.30 | 1.005 | −1.509 | 1.961 |

| [INT6] I love to recommend others to go for the services of Islamic banks. | 4.19 | 1.031 | −1.211 | 0.927 |

| [INT7] I must not delay of using services of Islamic banks. | 4.15 | 1.066 | −1.204 | 0.811 |

| Constructs and Items | VIF | FL | CA | rho_A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islamic value (reflective scale). | 0.842 | 0.843 | 0.894 | 0.680 | ||

| Islamic financial bodies and institutions that offer Islamic financing which is based on Islamic law. | 1.940 | 0.839 | ||||

| Muslims are not allowed to be connected with any kind of interest as provided by conventional institutions. | 1.492 | 0.750 | ||||

| Religious obligation motivates me to go for Islamic financing. | 2.235 | 0.846 | ||||

| Being a Muslim, I must use Islamic financing. | 2.301 | 0.858 | ||||

| Financial Literacy (reflective scale). | 0.862 | 0.915 | 0.928 | 0.619 | ||

| Islamic financing is free from interest. | - | - | ||||

| Gharar means deception and uncertainty that has no place in Islamic finance. | - | - | ||||

| To buy shares on a short-term basis, up and down of price is not speculation. | - | - | ||||

| Preserving assets is one of Islamic finance principles. | 1.956 | 0.776 | ||||

| Selling of a commodity is permitted in Islam before it fully comes under our control. | - | - | ||||

| Islamic banks provides lease banking (Ijarah). | 1.798 | 0.738 | ||||

| In Ijara, the wealth usually does not go back to the owner. | - | - | ||||

| Based on profit-loss sharing principle (Musharakah), Islamic banks provide money. | 2.009 | 0.740 | ||||

| Based on profit-loss sharing principle (Mudarabah), Islamic banks might invest you. | 2.621 | 0.831 | ||||

| Qardul Hassanah or benevolent loans might be provided by Islamic banks. | 2.019 | 0.771 | ||||

| Trade banking methods or Murabahah is provided by Islamic banks. | 2.686 | 0.846 | ||||

| Borrowers are those who purchase goods in an Islamic finance trade credit management system or Murabahah. | 2.170 | 0.786 | ||||

| Industrial banking service (Istisna) is offered by Islamic banks. | 2.309 | 0.801 | ||||

| Ethical Organisation (reflective scale). | 0.859 | 0.861 | 0.904 | 0.703 | ||

| Islamic banks are not involved in unethical activities. | 2.087 | 0.843 | ||||

| Islamic bank does not invest in unlawful activities. | 1.854 | 0.805 | ||||

| Islamic banks are an ethical organisation. | 2.150 | 0.834 | ||||

| I do love to take ethical banking services. | - | - | ||||

| In Islamic banks, equal treatment is provided to each and every customer. | - | - | ||||

| I can trust Islamic banks. | 2.338 | 0.871 | ||||

| Reputation (reflective scale). | 0.899 | 0.899 | 0.917 | 0.832 | ||

| Islamic financial bodies and institutions are concerned to uplift the image and reputation of Islam through their actions. | 2.877 | 0.914 | ||||

| Islamic financial bodies and institutions are greatly concerned to serve for the welfare of society through charity works, scholarships, donations, etc. | 2.886 | 0.916 | ||||

| Islamic financial bodies and institutions are greatly concerned not only maximizing profits, rather they are concerned to upgrade the living standard of the people and to serve for the welfare of society. | 2.603 | 0.906 | ||||

| Attitude (reflective scale). | 0.841 | 0.915 | 0.904 | 0.739 | ||

| Choosing the services of Islamic banks is a good idea. | 2.926 | 0.877 | ||||

| I do like to choose services provided by Islamic banks. | 2.964 | 0.873 | ||||

| Most of the people in my surrounding are taking services and products of Islamic banks. | 2.213 | 0.820 | ||||

| All the members in my family prefer to use the services of Islamic banks. | 2.057 | 0.889 | ||||

| Most of my friends think to choose services of Islamic banks. | 2.397 | 0.836 | ||||

| Intention (reflective scale). | 0.811 | 0.921 | 0.910 | 0.772 | ||

| In future, I am inclined to receive services and products of Islamic banks (Halal). | 2.568 | 0.886 | ||||

| I shall consider services of Islamic banks (Halal). | 2.885 | 0.888 | ||||

| I feel interested in receiving Islamic banking services. | 2.714 | 0.913 | ||||

| I feel interested in using Islamic banking products in future. | 2.210 | 0.897 | ||||

| I love to go for services Islamic banks. | 2.175 | 0.871 | ||||

| I love to recommend others to go for services of Islamic banks. | 1.014 | 0.849 | ||||

| I must not delay of using services of Islamic banks. | 2.915 | 0.846 |

| ATT | EO | IFL | INT | IV | RT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornell–Larcker criterion | ||||||

| ATT | 0.860 | |||||

| EO | 0.795 | 0.839 | ||||

| IFL | 0.678 | 0.750 | 0.787 | |||

| INT | 0.799 | 0.732 | 0.652 | 0.879 | ||

| IV | 0.757 | 0.850 | 0.763 | 0.704 | 0.824 | |

| RT | 0.790 | 0.805 | 0.715 | 0.671 | 0.775 | 0.912 |

| HTMT ratio | ||||||

| ATT | ||||||

| EO | 0.896 | |||||

| IFL | 0.737 | 0.843 | ||||

| INT | 0.855 | 0.809 | 0.698 | |||

| IV | 0.862 | 0.698 | 0.670 | 0.788 | ||

| RT | 0.871 | 0.614 | 0.687 | 0.625 | 0.791 | |

| Cross loadings | ||||||

| ATT1 | 0.877 | 0.747 | 0.647 | 0.720 | 0.700 | 0.756 |

| ATT2 | 0.873 | 0.720 | 0.609 | 0.741 | 0.686 | 0.685 |

| ATT3 | 0.820 | 0.617 | 0.488 | 0.605 | 0.598 | 0.655 |

| ATT4 | 0.889 | 0.686 | 0.611 | 0.716 | 0.646 | 0.661 |

| ATT5 | 0.836 | 0.637 | 0.544 | 0.639 | 0.614 | 0.630 |

| EO1 | 0.657 | 0.843 | 0.624 | 0.595 | 0.750 | 0.657 |

| EO2 | 0.650 | 0.805 | 0.650 | 0.630 | 0.667 | 0.615 |

| EO3 | 0.648 | 0.834 | 0.582 | 0.573 | 0.678 | 0.665 |

| EO6 | 0.711 | 0.871 | 0.658 | 0.655 | 0.752 | 0.755 |

| FL10 | 0.533 | 0.563 | 0.771 | 0.513 | 0.558 | 0.550 |

| FL11 | 0.580 | 0.643 | 0.846 | 0.553 | 0.642 | 0.605 |

| FL12 | 0.493 | 0.548 | 0.786 | 0.495 | 0.556 | 0.516 |

| FL13 | 0.529 | 0.613 | 0.801 | 0.513 | 0.633 | 0.598 |

| FL4 | 0.584 | 0.678 | 0.776 | 0.539 | 0.650 | 0.607 |

| FL6 | 0.483 | 0.533 | 0.738 | 0.456 | 0.577 | 0.530 |

| FL8 | 0.464 | 0.512 | 0.740 | 0.454 | 0.534 | 0.498 |

| FL9 | 0.581 | 0.607 | 0.831 | 0.567 | 0.638 | 0.578 |

| INT1 | 0.734 | 0.707 | 0.599 | 0.886 | 0.642 | 0.622 |

| INT2 | 0.699 | 0.661 | 0.566 | 0.888 | 0.635 | 0.613 |

| INT3 | 0.708 | 0.675 | 0.598 | 0.913 | 0.649 | 0.585 |

| INT4 | 0.706 | 0.656 | 0.583 | 0.897 | 0.642 | 0.571 |

| INT5 | 0.709 | 0.645 | 0.603 | 0.871 | 0.613 | 0.620 |

| INT6 | 0.687 | 0.567 | 0.539 | 0.849 | 0.572 | 0.546 |

| INT7 | 0.669 | 0.586 | 0.519 | 0.846 | 0.575 | 0.564 |

| IV1 | 0.640 | 0.706 | 0.658 | 0.561 | 0.839 | 0.682 |

| IV2 | 0.603 | 0.625 | 0.693 | 0.617 | 0.750 | 0.565 |

| IV3 | 0.621 | 0.732 | 0.567 | 0.549 | 0.846 | 0.664 |

| IV4 | 0.631 | 0.734 | 0.599 | 0.597 | 0.858 | 0.641 |

| RT1 | 0.710 | 0.729 | 0.632 | 0.572 | 0.712 | 0.914 |

| RT2 | 0.723 | 0.748 | 0.684 | 0.650 | 0.728 | 0.916 |

| RT3 | 0.727 | 0.723 | 0.638 | 0.611 | 0.682 | 0.906 |

| Beta | SD | T-Values | R2 | f2 | Q2 | p-Values | Decisions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: IV -> ATT | 0.147 | 0.063 | 2.340 | 0.445 | 0.019 | Accepted | ||

| H2: IFL -> ATT | 0.049 | 0.046 | 1.068 | 0.025 | 0.286 | Not accepted | ||

| H3: EO -> ATT | 0.335 | 0.076 | 4.436 | 0.082 | 0.000 | Accepted | ||

| H4: RT -> ATT | 0.371 | 0.071 | 5.229 | 0.704 | 0.768 | 0.513 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H5: ATT -> INT | 0.799 | 0.027 | 29.412 | 0.639 | 0.542 | 0.488 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Mediating effect | ||||||||

| Ha: IV -> ATT -> INT | 0.117 | 0.050 | 2.325 | 0.020 | Mediating | |||

| Hb: IFL -> ATT -> INT | 0.040 | 0.037 | 1.067 | 0.286 | Not mediating | |||

| Hc: EO -> ATT -> INT | 0.268 | 0.062 | 4.315 | 0.000 | Mediating | |||

| Hd: RT-> ATT -> INT | 0.297 | 0.057 | 5.208 | 0.000 | Mediating | |||

| Dimensions | Importance | Performance |

|---|---|---|

| IV | 0.117 | 77.275 |

| IFL | 0.040 | 77.432 |

| EO | 0.268 | 80.254 |

| RT | 0.297 | 76.822 |

| ATT | 0.799 | 79.287 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoque, M.N.; Rahman, M.K.; Said, J.; Begum, F.; Hossain, M.M. What Factors Influence Customer Attitudes and Mindsets towards the Use of Services and Products of Islamic Banks in Bangladesh? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084703

Hoque MN, Rahman MK, Said J, Begum F, Hossain MM. What Factors Influence Customer Attitudes and Mindsets towards the Use of Services and Products of Islamic Banks in Bangladesh? Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084703

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoque, Muhammad Nazmul, Muhammad Khalilur Rahman, Jamaliah Said, Farhana Begum, and Mohammad Mainul Hossain. 2022. "What Factors Influence Customer Attitudes and Mindsets towards the Use of Services and Products of Islamic Banks in Bangladesh?" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084703

APA StyleHoque, M. N., Rahman, M. K., Said, J., Begum, F., & Hossain, M. M. (2022). What Factors Influence Customer Attitudes and Mindsets towards the Use of Services and Products of Islamic Banks in Bangladesh? Sustainability, 14(8), 4703. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084703