The Role of Self-Efficacy as a Mediating Variable in CareerEDGE Employability Model: The Context of Undergraduate Employability in the North-East Region of Nigeria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Employability in the North-East Region of Nigeria

2.2. Employability in Higher Education

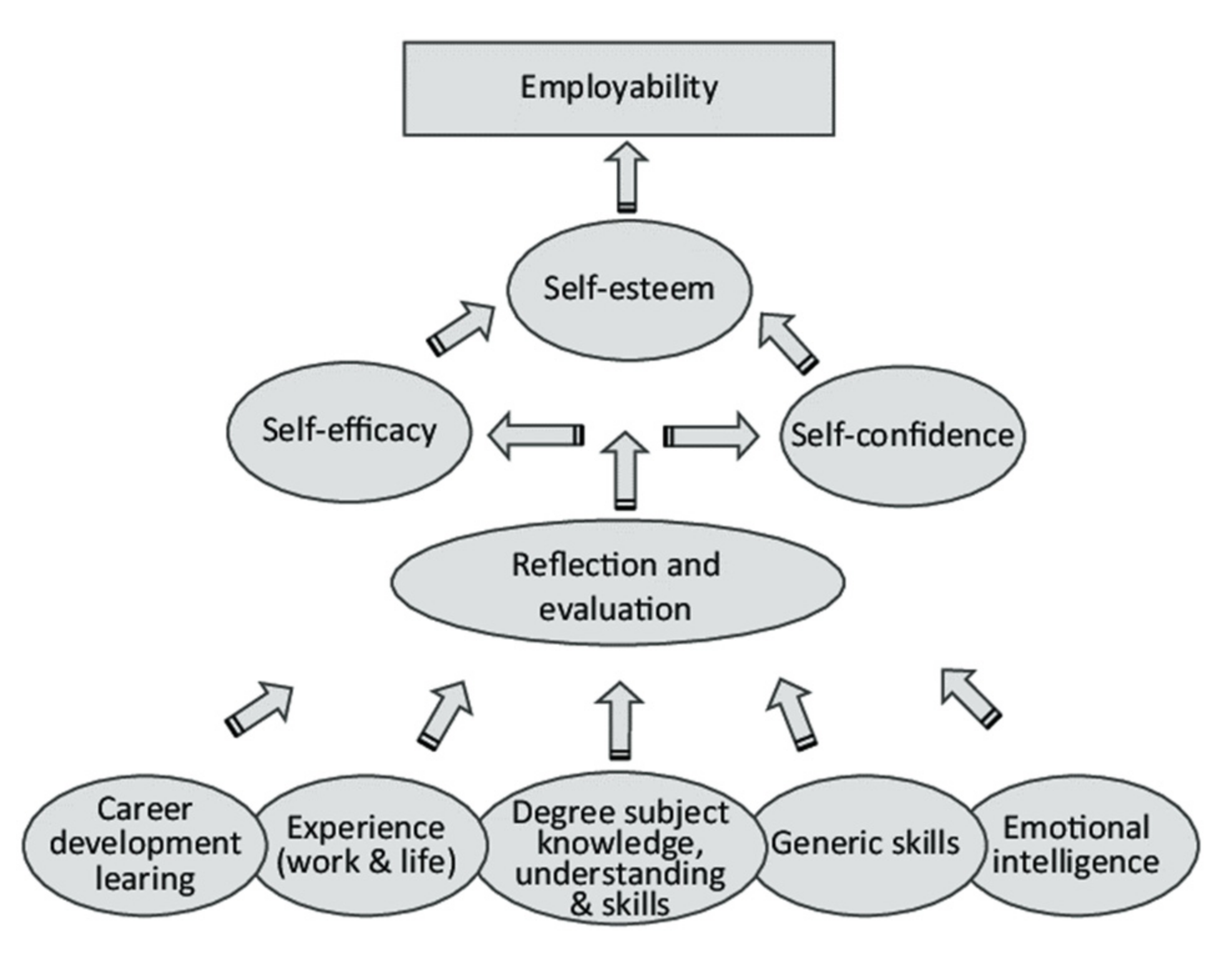

2.3. CareerEDGE Employability Model

2.3.1. Career Development Learning and Employability

2.3.2. Work and Life Experience and Employability

2.3.3. Degree Subject Knowledge and Understanding and Employability

2.3.4. Generic Skills and Employability

2.3.5. Emotional Intelligence and Employability

2.3.6. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design, Sampling, and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Data Analysis

5. Findings

5.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Study Variables

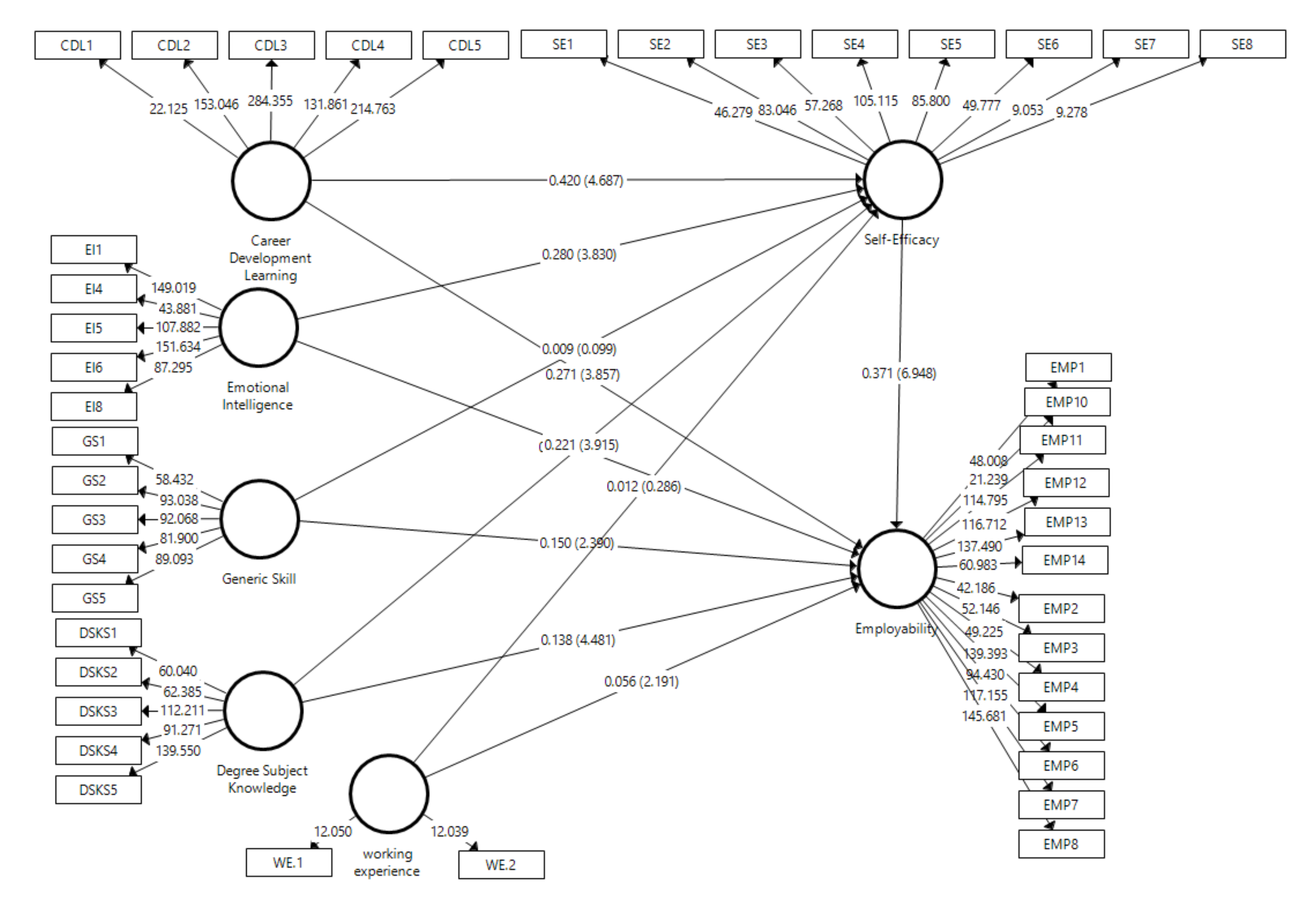

5.2. Measurement Model Assessment

5.3. Structural Model Assessment

6. Discussion and Implications

7. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva, P.; Lopes, B.; Costa, M.; Seabra, D.; Melo, A.I.; Brito, E.; Dias, G.P. Stairway to Employment? Internships in Higher Education. High. Educ. 2016, 72, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derecskei, A.K.; Pawliczek, A. Talent Management as An Effect of Globalization in Case of Visegrad 4 Countries; University of Zilina: Žilina, Slovakia, 2018; Volume 10, pp. 1143–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Pauceanu, A.M.; Rabie, N.; Moustafa, A. Employability under the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 13, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, L.; Shacklock, K.; Marchant, T. Employability: A Contemporary Review for Higher Education Stakeholders. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2018, 70, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitan, O.S. Towards Enhancing University Graduate Employability in Nigeria. J. Sociol. Soc. Anthropol. 2016, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, L.D.; Sewell, P. The Key to Employability: Developing a Practical Model of Graduate Employability. Educ. Train. 2007, 49, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, P.K.; O’Mahoney, J.; Vincent, S. Studying Organizations Using Critical Realism: A Practical Guide; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kanfer, R.; Wanberg, C.R.; Kantrowitz, T.M. Job Search and Employment: A Personality–Motivational Analysis and Meta-Analytic Review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 837–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, L.M.; Roehling, M.V.; LePine, M.A.; Boswell, W.R. A Longitudinal Study of the Relationships among Job Search Self-Efficacy, Job Interviews, and Employment Outcomes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2003, 18, 207–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Juang, L.P.; Silbereisen, R.K. Self-Efficacy and Successful School-to-Work Transition: A Longitudinal Study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Sanders, K. The Role of Job Satisfaction and Self-Efficacy as Mediating Mechanisms in the Employability and Affective Organizational Commitment Relationship: A Case from a Pakistani University. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 54, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, L.D.; Qualter, P.; Sewell, P.J. Exploring the Factor Structure of the CareerEDGE Employability Development Profile. Educ. Train. 2014, 56, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, A.D. A Review of Empirical Studies on Employability and Measures of Employability. In Psychology of Career Adaptability, Employability and Resilience; Maree, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, D.J.; Hamilton, L.K.; Baldwin, R.; Zehner, M. An Exploratory Study of Factors Affecting Undergraduate Employability. Educ. Train. 2013, 55, 681–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Social Statistics in Nigeria; NBS Publications: Lagos, Nigeria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- BBC Nigerians Living in Poverty Rise to Nearly 61%. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-17015873 (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Meagher, K. Beyond Terror: Addressing the Boko Haram Challenge in Nigeria; Norwegian Peace Building Resource Center Policy Brief: Oslo, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations World Economic Situation and Prospects 2019; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Römgens, I.; Scoupe, R.; Beausaert, S. Unraveling the Concept of Employability, Bringing Together Research on Employability in Higher Education and the Workplace. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 2588–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y. Graduate Employability: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Employers’ Perceptions. High. Educ. 2013, 65, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M. Rethinking Graduate Employability: The Role of Capital, Individual Attributes and Context. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1923–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorke, M. Employability in Higher Education: What It Is-What It Is Not; Higher Education Academy York: York, UK, 2006; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tsitskari, E.; Goudas, M.; Tsalouchou, E.; Michalopoulou, M. Employers’ Expectations of the Employability Skills Needed in the Sport and Recreation Environment. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Investment in Human Capital: Effects on Earnings. In Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, 2nd ed.; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1975; pp. 13–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yawson, D.E.; Yamoah, F.A. Understanding Pedagogical Essentials of Employability Embedded Curricula for Business School Undergraduates: A Multi-Generational Cohort Perspective. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2020, 5, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, B.; Watts, A.G. The Dots Analysis; National Institute for Careers Education and Counselling, The Career-Learning NETWORK: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yorke, M.; Knight, P. Self-Theories: Some Implications for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Stud. High. Educ. 2004, 29, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copps, J.; Plimmer, D. The Journey to Employment: A Guide to Understanding and Measuring What Matters for Young People; NPC: UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, N.; Dunne, E.; Carré, C. Patterns of Core and Generic Skill Provision in Higher Education. High. Educ. 1999, 37, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Chen, X. Continuance Intention to Use MOOCs: Integrating the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Task Technology Fit (TTF) Model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 67, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, K. Developing Employability Skills; Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory: Portland, OR, USA, 1993; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Rasdi, R.; Ahrari, S. The Applicability of Social Cognitive Career Theory in Predicting Life Satisfaction of University Students: A Meta-Analytic Path Analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojonugwa, O.I.; Hamzah, R.; Bakar, A.R.; Rashid, A.M. Evaluating Self-Efficacy Expected of Polytechnic Engineering Students as a Measure of Employability. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 2015, 3, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gbadamosi, G.; Evans, C.; Richardson, M.; Ridolfo, M. Employability and Students’ Part-Time Work in the UK: Does Self-Efficacy and Career Aspiration Matter? Br. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 41, 1086–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, S. Second Life in Higher Education: Assessing the Potential for and the Barriers to Deploying Virtual Worlds in Learning and Teaching. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2009, 40, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-L.; McKenzie, S. Using Career Development Learning in Science and Information Technology Courses to Build 21st-Century Learners. J. Contin. High. Educ. 2018, 66, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, A.G. Career Development Learning and Employability; Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Salape, R.C.; Cuevas, E.G. The Link between Career Development Learning and Employability Skills of Senior High School Students. Univ. Mindanao Int. Multidiscip. Res. J. 2020, 5, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ariffin, H.F.; Raja-Abdullah, R.P.S.; Baba, N.; Hashim, S. Structural Relationships between Career Development Learning, Work Integrated Learning and Employability: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. In Proceedings of the Theory and Practice in Hospitality and Tourism Research-Proceedings of the 2nd International Hospitality and Tourism Conference, Penang, Malaysia, 2–4 September 2014; pp. 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Callanan, G.; Benzing, C. Assessing the Role of Internships in the Career-Oriented Employment of Graduating College Students. Educ. Train. 2004, 46, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gault, J.; Leach, E.; Duey, M. Effects of Business Internships on Job Marketability: The Employers’ Perspective. Educ. Train. 2010, 52, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hopkins, C.D.; Raymond, M.A.; Carlson, L. Educating Students to Give Them a Sustainable Competitive Advantage. J. Mark. Educ. 2011, 33, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.C.; Mohd Rasdi, R.; Samah, B.A.; Wahat, N.W.A. Promoting Protean Career through Employability Culture and Mentoring: Career Strategies as Moderator. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2017, 41, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaretta, G.; Triventi, M. Work Experience during Higher Education and Post-Graduation Occupational Outcomes: A Comparative Study on Four European Countries. Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 2015, 56, 232–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, L. What Barriers Do Deaf Undergraduates Face in Acquiring Employability Skills in Higher Education? J. Incl. Pract. Furth. High. Educ. 2019, 11, 118–138. [Google Scholar]

- Atlay, M.; Harris, R. An Institutional Approach to Developing Students”transferable’skills. Innov. Educ. Train. Int. 2000, 37, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, L.D. Developing Graduate Employability: The CareerEDGE Model and the Importance of Emotional Intelligence. In Graduate Employability in Context; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 317–338. [Google Scholar]

- Cranmer, S. Enhancing Graduate Employability: Best Intentions and Mixed Outcomes. Stud. High. Educ. 2006, 31, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. Employability of Geography Graduates in the GIS and GI-Related Fields. Planet 2004, 13, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Overton, T.; Thompson, C.D.; Rayner, G. Academics’ Perspectives of the Teaching and Development of Generic Employability Skills in Science Curricula. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons-Wood, D.; Lange, T. Developing Core Skills–Lessons from Germany and Sweden. Educ. Train. 2000, 42, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferns, S. Graduate Employability: Teaching Staff, Employer and Graduate Perceptions. In Proceedings of the Australian Collaborative Education Network (ACEN) National Conference, Deakin University, Geelong, Australia, 29 October–2 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lowden, D.; Hall, S.; Elliot, D.; Lewin, J. IntelligencResearch Commissioned by the Edge Foundation; Research commissioned by the Edge Foundation; Edge Foundation: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Kularatne, I. Relationship between Generic Skills and Employability Skills: An Exploratory Study in the Context of New Zealand Postgraduate Education. Management 2020, 15, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Overton, T.; Thompson, C.; Rayner, G. Graduate Employability: Views of Recent Science Graduates and Employers. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Math. Educ. 2016, 24, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Paik, Y.; Seo, M.-G.; Jin, S. Affective Information Processing in Self-Managing Teams: The Role of Emotional Intelligence. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2019, 55, 235–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manichander, T. Emotional Intelligence of Graduate Students. Res. Tracks 2020, 7, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Kinicki, A.J.; Ashforth, B.E. Employability: A Psycho-Social Construct, Its Dimensions, and Applications. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 65, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, S.R.; Kai Le, K.; Musa, S.N.S. The Mediating Role of Career Decision Self-Efficacy on the Relationship of Career Emotional Intelligence and Self-Esteem with Career Adaptability among University Students. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2021, 26, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vroom, V.H. Work and Motivation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Pool, L.D.; Qualter, P. Emotional Self-Efficacy, Graduate Employability, and Career Satisfaction: Testing the Associations. Aust. J. Psychol. 2013, 65, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a Unifying Social Cognitive Theory of Career and Academic Interest, Choice, and Performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Peng, M.Y.-P.; Anser, M.K.; Chong, W.-L.; Lin, B. Key Teacher Attitudes for Sustainable Development of Student Employability by Social Cognitive Career Theory: The Mediating Roles of Self-Efficacy and Problem-Based Learning. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Qian, Z.; Wang, D. How Does the Servant Supervisor Influence the Employability of Postgraduates? Exploring the Mechanisms of Self-Efficacy and Academic Engagement. Front. Bus. Res. China 2020, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, D.S. A-Priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models; 2018. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89 (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Raybould, M.; Wilkins, H. Over Qualified and under Experienced: Turning Graduates into Hospitality Managers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, G.; Gully, S.M.; Eden, D. Validation of a New General Self-Efficacy Scale. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rothwell, A.; Herbert, I.; Rothwell, F. Self-Perceived Employability: Construction and Initial Validation of a Scale for University Students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing Measurement Model Quality in PLS-SEM Using Confirmatory Composite Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In New challenges to international marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Y.; Szűcs, N.; Gunz, H. Career Studies in Search of Theory: The Rise and Rise of Concepts. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, S. The Opportunities and Challenges for Employability-Related Support in STEM Degrees. New Dir. Teach. Phys. Sci. 2016, 11, n1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stiwne, E.E.; Jungert, T. Engineering Students’ Experiences of Transition from Study to Work. J. Educ. Work 2010, 23, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, U.C.; Nwajiuba, C.A.; Binuomote, M.O.; Ehiobuche, C.; Igu, N.C.N.; Ajoke, O.S. Career Training with Mentoring Programs in Higher Education: Facilitating Career Development and Employability of Graduates. Educ. Train. 2020, 62, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwajiuba, C.A.; Igwe, P.A.; Akinsola-Obatolu, A.D.; Ituma, A.; Binuomote, M.O. What Can Be Done to Improve Higher Education Quality and Graduate Employability in Nigeria? A Stakeholder Approach. Ind. High. Educ. 2020, 34, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, R.; Gupta, P.; Misra, R. Employability Skills Framework: A Tripartite Approach. Educ. Train. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Tomlinson, M. Investigating the Relationship between Career Planning, Proactivity and Employability Perceptions among Higher Education Students in Uncertain Labour Market Conditions. High. Educ. 2020, 80, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvas, P.; Gao, S.; Shen, Y.; Bawany, B. Sharing Higher Education’s Promise beyond the Few in Sub-Saharan Africa; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Varghese, J.S.; Patel, S.A.; Martorell, R.; Ramirez-Zea, M.; Stein, A.D. Relative and Absolute Wealth Mobility since Birth in Relation to Health and Human Capital in Middle Adulthood: An Analysis of a Guatemalan Birth Cohort. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 15, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M.; Beukes, C.J. Employability, Emotional Intelligence and Career Preparation Support Satisfaction among Adolescents in the School-to-Work Transition Phase. J. Psychol. Afr. 2010, 20, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayar, S.; Fiori, M.; Thalmayer, A.G.; Rossier, J. Investigating the Link between Trait Emotional Intelligence, Career Indecision, and Self-Perceived Employability: The Role of Career Adaptability. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 135, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional Intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; George-Curran, R.; Smith, M.L. The Role of Emotional Intelligence in the Career Commitment and Decision-Making Process. J. Career Assess. 2003, 11, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Chen, H.; Pang, L.; Gu, X. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy of Chinese Vocational College Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Jenkins-Guarnieri, M.A.; Murdock, J.L. Career Development among First-Year College Students: College Self-Efficacy, Student Persistence, and Academic Success. J. Career Dev. 2013, 40, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 16–20 | 111 | 42.0 |

| 21–25 | 67 | 25.4 |

| 30 | 54 | 20.5 |

| >30 | 32 | 12.1 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 140 | 53.0 |

| Female | 124 | 47.0 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 153 | 58.0 |

| Married | 69 | 26.1 |

| Widowed | 27 | 10.2 |

| Divorced | 15 | 5.7 |

| University | ||

| Maiduguri | 60 | 22.7 |

| Damaturu | 50 | 18.9 |

| Gashua | 30 | 11.4 |

| Bauchi | 43 | 16.3 |

| Gombe | 33 | 12.5 |

| Yola | 48 | 18.2 |

| Faculty | ||

| Agriculture | 50 | 18.9 |

| Engineering | 32 | 12.1 |

| Management | 182 | 68.9 |

| Parent’s Occupation | ||

| Civil servant | 18 | 6.8 |

| Business | 26 | 9.8 |

| Farmer | 220 | 83.3 |

| Construct | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SE | 3.78 | 1.1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. DSKS | 3.57 | 1.25 | 0.472 ** | 1 | |||||

| 3. GS | 3.15 | 1.35 | 0.618 ** | 0.350 ** | 1 | ||||

| 4. CDL | 3.28 | 1.43 | 0.662 ** | 0.324 ** | 0.867 ** | 1 | |||

| 5. EI | 3.1 | 1.05 | 0.423 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.474 ** | 0.469 ** | 1 | ||

| 6. EMP | 3.08 | 1.14 | 0.819 ** | 0.548 ** | 0.774 ** | 0.801 ** | 0.471 ** | 1 | |

| 7. WE | 3.23 | 1.39 | 0.344 ** | 0.158 ** | 0.482 ** | 0.439 ** | 0.617 ** | 0.354 ** | 1 |

| Constructs | α | Rho_A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDL | 0.95 | 0.957 | 0.962 | 0.837 |

| DSKS | 0.955 | 0.957 | 0.966 | 0.849 |

| EI | 0.953 | 0.953 | 0.964 | 0.841 |

| EMP | 0.978 | 0.979 | 0.98 | 0.793 |

| GS | 0.949 | 0.953 | 0.961 | 0.831 |

| SE | 0.923 | 0.942 | 0.94 | 0.67 |

| WE | 0.907 | 0.915 | 0.956 | 0.915 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CDL | 0.915 | ||||||

| 2. DSKS | 0.324 | 0.921 | |||||

| 3. EI | 0.641 | 0.427 | 0.917 | ||||

| 4. EMP | 0.806 | 0.542 | 0.743 | 0.89 | |||

| 5. GS | 0.865 | 0.353 | 0.68 | 0.787 | 0.911 | ||

| 6. SE | 0.679 | 0.483 | 0.65 | 0.831 | 0.641 | 0.818 | |

| 7. WE | 0.007 | 0.221 | −0.027 | 0.109 | 0.028 | 0.057 | 0.957 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CDL | ||||||

| 2. DSKS | 0.342 | |||||

| 3. EI | 0.679 | 0.445 | ||||

| 4. EMP | 0.835 | 0.561 | 0.768 | |||

| 5. GS | 0.814 | 0.368 | 0.717 | 0.809 | ||

| 6. SE | 0.722 | 0.521 | 0.692 | 0.687 | 0.682 | |

| 7. WE | 0.016 | 0.237 | 0.036 | 0.117 | 0.039 | 0.077 |

| Hypotheses | Relationships | Std β | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P | BC 95% LL | BC 95% UL | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CDL→EMP | 0.271 | 3.857 | 0 | 0.145 | 0.399 | SU |

| H2 | DSKS→EMP | 0.138 | 4.81 | 0 | 0.078 | 0.206 | SU |

| H3 | EI→EMP | 0.169 | 3.830 | 0.001 | 0.077 | 0.267 | SU |

| H4 | GS→EMP | 0.15 | 2.390 | 0.031 | 0.013 | 0.291 | SU |

| H5 | WE→EMP | 0.056 | 2.191 | 0.028 | 0.009 | 0.106 | SU |

| H6a | CDL→SE→EMP | 0.156 | 3.876 | 0 | 0.082 | 0.237 | SU |

| H6b | DSKS→SE→EMP | 0.082 | 3.424 | 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.132 | SU |

| H6c | EI→SE→EMP | 0.104 | 3.200 | 0.001 | 0.045 | 0.164 | SU |

| H6d | GS→SE→EMP | 0.003 | 0.097 | 0.922 | −0.069 | 0.073 | NS |

| H6e | WE→SE→EMP | 0.005 | 0.280 | 0.776 | −0.026 | 0.037 | NS |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wujema, B.K.; Mohd Rasdi, R.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Ahrari, S. The Role of Self-Efficacy as a Mediating Variable in CareerEDGE Employability Model: The Context of Undergraduate Employability in the North-East Region of Nigeria. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084660

Wujema BK, Mohd Rasdi R, Zaremohzzabieh Z, Ahrari S. The Role of Self-Efficacy as a Mediating Variable in CareerEDGE Employability Model: The Context of Undergraduate Employability in the North-East Region of Nigeria. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084660

Chicago/Turabian StyleWujema, Baba Kachalla, Roziah Mohd Rasdi, Zeinab Zaremohzzabieh, and Seyedali Ahrari. 2022. "The Role of Self-Efficacy as a Mediating Variable in CareerEDGE Employability Model: The Context of Undergraduate Employability in the North-East Region of Nigeria" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084660

APA StyleWujema, B. K., Mohd Rasdi, R., Zaremohzzabieh, Z., & Ahrari, S. (2022). The Role of Self-Efficacy as a Mediating Variable in CareerEDGE Employability Model: The Context of Undergraduate Employability in the North-East Region of Nigeria. Sustainability, 14(8), 4660. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084660