1. Introduction

The European Union has been striving for equality between men and women since its inception, and gender equality is currently included in all its policies. Equality between men and women is a fundamental value of the European Union enshrined in the Treaties and is one of the objectives and tasks of the European Union. The EU gender equality policies are currently one of the main pillars of activities that promote gender equality in Europe. The mapping of European gender equality policies raises the issue of interventions at various levels, from individuals, households, civil society, and the state to the European Community itself. Gender equality policies aimed at enabling women to achieve equality with men (anti-gender discrimination policies, parental leave policies, and equal opportunities policies) have brought women into the labor market and supported their ability to care for children and families.

The main official European gender policy is gender mainstreaming. It represents an innovative principle, as it stands a tactical shift from targeting only women’s issues to a broader perspective of gender relations. Gender mainstreaming adopts a horizontal approach—a cross-cutting supra-ministerial policy—where equality between women and men can only be achieved if it is set as an objective in all other policies. Its main goal is to eliminate the disadvantaged position of people in society on the basis of gender. There are already academic contributions declaring such an attitude of the EU in its United in Diversity motto and policy [

1,

2].

In our research article, we expect that the job attitudes of men and women converge and their declared different preferences for job attributes decrease. We also expect that the preference for job attributes aimed at comfortable working conditions is closer between men and women due to the growing balance of men’s and women’s role distribution within the household. Therefore, the main goal of the research, using quantitative research methods and using data from the European Values Study (EVS), is to identify the gender differences in the preferences for paid job attributes in selected EU countries. More specifically, our goals are to identify the importance of work for men and women; to identify the job attributes with the greatest gender differences within the selected countries; to find out the degree of preference for external and internal job attributes in the examined countries; to map the inclination of gender stereotypes; and to identify attitudes to the division of gender roles and to compare the level of gender equality and the preference for job attributes in the examined EU countries.

2. Measurement and Classification of Job Attributes: A Literature Review

The relevant literature emphasizes the importance of job attributes (values), especially for job satisfaction and commitment. Job attributes are characterized as values that define the general motivation to work. They define the general meaning of work in human life, as well as compliance with existing standards. They are also often guidelines for employers in selecting suitable employees [

3]. According to Busch-Heizmann [

4], one of the useful methods of empirically examining the preferences of job attributes is to look at job values or attributes that individuals rate as important or satisfactory for their work. However, the findings of some national and international studies on gender differences in job attributes are mixed: some confirm a higher value of external job attributes in men (high income) in line with supply side theory [

5,

6], others do not suggest any gender differences [

7,

8]. A research article from Spain concludes that women are more job-satisfied than men [

9].

Rokeach [

10] defines values as useful indicators of an individual’s decisions and actions that are lasting and relatively resilient to change. Although there is some disagreement in the distinction between general values and job values (attributes), job attributes have been defined by several authors [

11,

12] as desired outcomes that people feel they should have achieved through work. Job attributes shape the perception of employee preferences in the workplace and have a direct impact on employees’ attitudes and behavior [

13].

Gesthuizen et al. [

3] state that job attributes are most often analyzed mainly in terms of their multiple causes—on an individual or contextual level—as well as in terms of their potential consequences for life satisfaction or economic self-sufficiency [

14,

15,

16]. Nevertheless, there is only a small amount of academic work on what we understand as job attributes/values or the relationship between work–life balance and career opportunities perception [

17]. However, some researchers analyze patterns and practices of males and females in paid and unpaid jobs as well as indicators of gendered attitudes to understand the changing practices [

18].

Additionally, the existing literature has not been much interested in whether the measurement of job attributes is accurate and comparable in different cultural contexts [

8,

19]. For example, research dedicated to agricultural businesses found out that women prefer the opportunity for self-development and good social relations, while for men, it is economic benefits and job-related prestige driving their job attitudes [

20]. In international research analyzing the most important determinants of job attributes, we assume these concepts and scales are understood in the same way but in different contexts. We assume that each measured item has the same meaning in individual countries. However, the meaning of certain terms may vary from country to country, as it depends on the cultural, economic and political environment in a given country [

3,

21]. This is in line with the findings of Hungarian and Danish authors claiming we know much less about what people actually do at their workplaces and the causes of within-occupation gender differences compared to relatively robust literature evidence on general gender differences in the labor market [

22,

23]. Although the literature agrees on two dimensions of the division of job attributes (external and internal), we are not sure whether these two dimensions are present or understood in the same way in each country. Burbano et al. prefer an approach that measures the gender differences in preferences for meaning at work directly, based on individual levels, i.e., derived from the job mission as opposed to from the job design [

24]. Zou argues that the gender gap in job satisfaction is a matter of heterogeneity in work orientation between men and women [

25]. According to Gesthuizen and Verbakel [

21], the institutional structure of a state, religious background or current labor market can have a major impact on the interpretation of items that are to measure a certain dimension of job attributes. In addition, surveys and studies usually use a large number of items measuring both external and internal job attributes, which raises the question of what pattern these items have in different cultural contexts [

3]. The changing patterns of gender discrimination may be volatile over time, while the preferences of job attributes help us to understand gender discrimination or segregation, as identified in the Swedish longitudinal study of occupational attributes [

26].

2.1. Classification of Job Attributes

The preference for job attributes may vary between individuals, and several authors approach the theoretical proposals for the structure of job attributes differently in their work, agreeing that job attributes are multidimensional. The individual attributes of a job can be categorized both theoretically and empirically. We base our research on the dichotomous division into external and internal job attributes. External job attributes represent tangible things such as income, vacation, career progression, working hours, or the pension system. We can also call external job attributes work characteristics associated with a favorable working conditions. Kaassa [

27] calls them external because they are external to the individual in their sense since, according to the author, there is no direct link between work tasks and the outcomes [

3]. The notion that external attributes such as salary, tangible assets and prestige are the primary factors that motivate people to work is as old as the scientific studies of work themselves. On the other hand, although modern organizational theory places less emphasis on external rewards (attributes), they still play an important role in the employment process [

28].

Internal job attributes mean motivation to work for the essence of work, rather than earning in-kind rewards (external attributes). A job that is interesting, provides diversity and responsibility, offers challenges, allows the employee to see the results of what he or she does, and has a significant impact on others is intrinsically motivating [

28]. The internal attributes of a job are a mirror image of the external ones: they describe the required content of the job, not its general circumstances. We could also call internal job attributes characteristics associated with self-realization at work. Some authors [

29,

30] talk about other job attributes that include: job stability, job security, leisure and vacation, or influence or autonomy in decision-making, altruism, social benefits, and social rewards related to interpersonal relationships at work.

In relation to job attributes, we also compare our data with results from the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), which is a unique tool for measuring the progress of gender mainstreaming in all areas of life for both men and women using the Gender Equality Index (GEI). It aims to raise the profile of areas for improvement and supports policy makers in proposing more effective gender equality measures. Through the Gender Equality Index, each Member State of the European Union has the opportunity to assess its level of gender equality, to compare itself with the other Member States, and to compare the progress made. The Gender Equality Index thus points out to individual EU countries where the political priorities of those countries should be shifted to speed up the process of achieving gender equality. The key areas of Gender Equality Index is illustrated in

Table 1 below.

2.2. Data and Methods

The main data set for our research comprises data from the European Value Study, which is the oldest longitudinal comparative survey of value orientation in Europe since 1983. Specifically, we focus on its last wave of 2017/2018 [

32]. We worked with an integrated data set containing data from 56,491 respondents from 34 countries. For EVS 2017, a single-stage or multi-stage representative sample selection of the adult population over 18 years of age was used. The sample size of the pre-participating countries was determined as the effective sample size: 1000 for countries with a population of less than 2 million and 1200 for countries with a population of more than 2 million. The sample proposals and other relevant information on their collection were reviewed by the EVS Methodology Group (EVS-MG) and approved before concluding a contract with the agency that carried out the data collection or before starting the data collection. In the case of field sampling, EVS-MG designed the necessary protocols to document the probabilities of each respondent’s selection, and sampling was documented using a sampling design form (SDF) provided by national teams.

We have been testing the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). There is a statistical dependence between the preference for external job attributes and the level of gender equality in EU countries.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). There is a statistical dependence between the preference for internal job attributes and the level of gender equality in EU countries.

Preference for external job attributes: An index created by combining three job attributes related to self-realization at work: good pay + good hours + generous holidays. Each attribute represented a variable that took on two values (marked/unmarked).

Preference for internal job attributes: An index created by combining three job attributes related to self-realization at work: An opportunity to use initiative + a job in which you feel you can achieve something + a responsible job. Each attribute represented a variable that took on two values (marked/unmarked).

EU Gender Equality Level: The Gender Equality Index (GEI) is measured by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). It is a number expressing the country’s score given to each EU country on the basis of a combination of six gender indicators/key areas: job, money, knowledge, power, time, and health. The index acquires a value (score) of 1 to 100 points, where 1 represents no level of gender equality and 100 represents the highest level of gender equality.

We have decided to include in the comparative analysis all countries that participated in the last wave of EVS, are in the integrated data set EVS2017, and are also part of the European Gender Equality Index. Out of the 28 EU countries surveyed in the Gender Equality Index, 20 have participated in the EVS. The research sample included 33,828 respondents from 20 selected EU countries. The resulting sample sizes for each country, as well as the ratio of women to men in each country, are shown in

Table 2.

We processed the data from the integrated EVS2017 file in the statistical software SPSS. We worked with the bivariate statistical method-second-level classification (contingency tables) and multivariate (multidimensional) statistical method for data reduction-correspondence analysis, which we used to verify research hypotheses. When testing research hypotheses, we will work with two hypotheses: the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Importance of Work

A frequent conclusion of several pieces of research and studies dealing with gender differences in the preference for job attributes is the claim that work is not as valuable for women as it is for men [

33,

34]. This is a fact that is mentioned as a possible cause of the existence of these gender differences. At the outset, therefore, we looked at the importance of the work itself in the lives of the people in the EU countries. EVS research has made this possible with its battery of questions, which are asked at the beginning of the questionnaire:

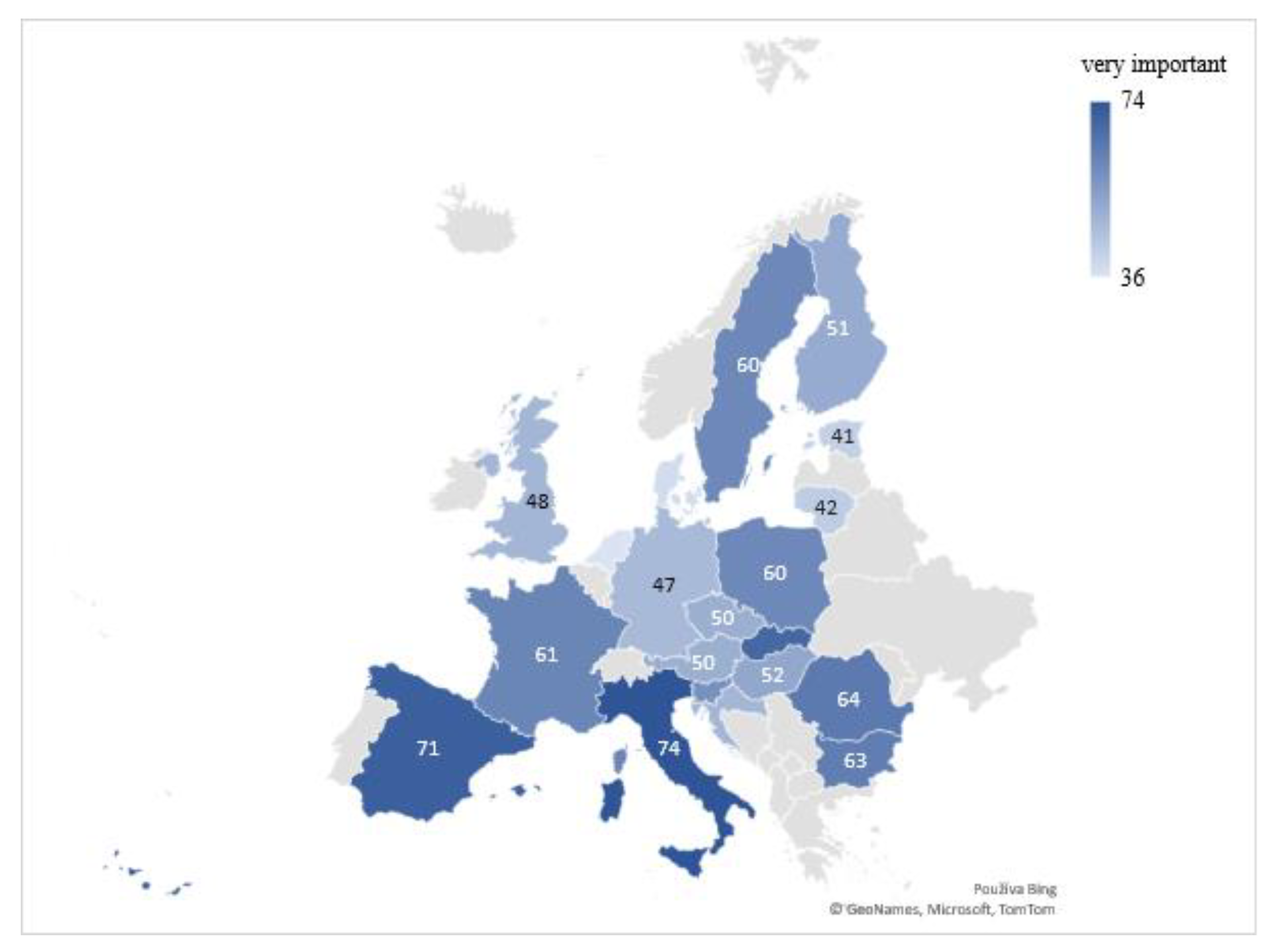

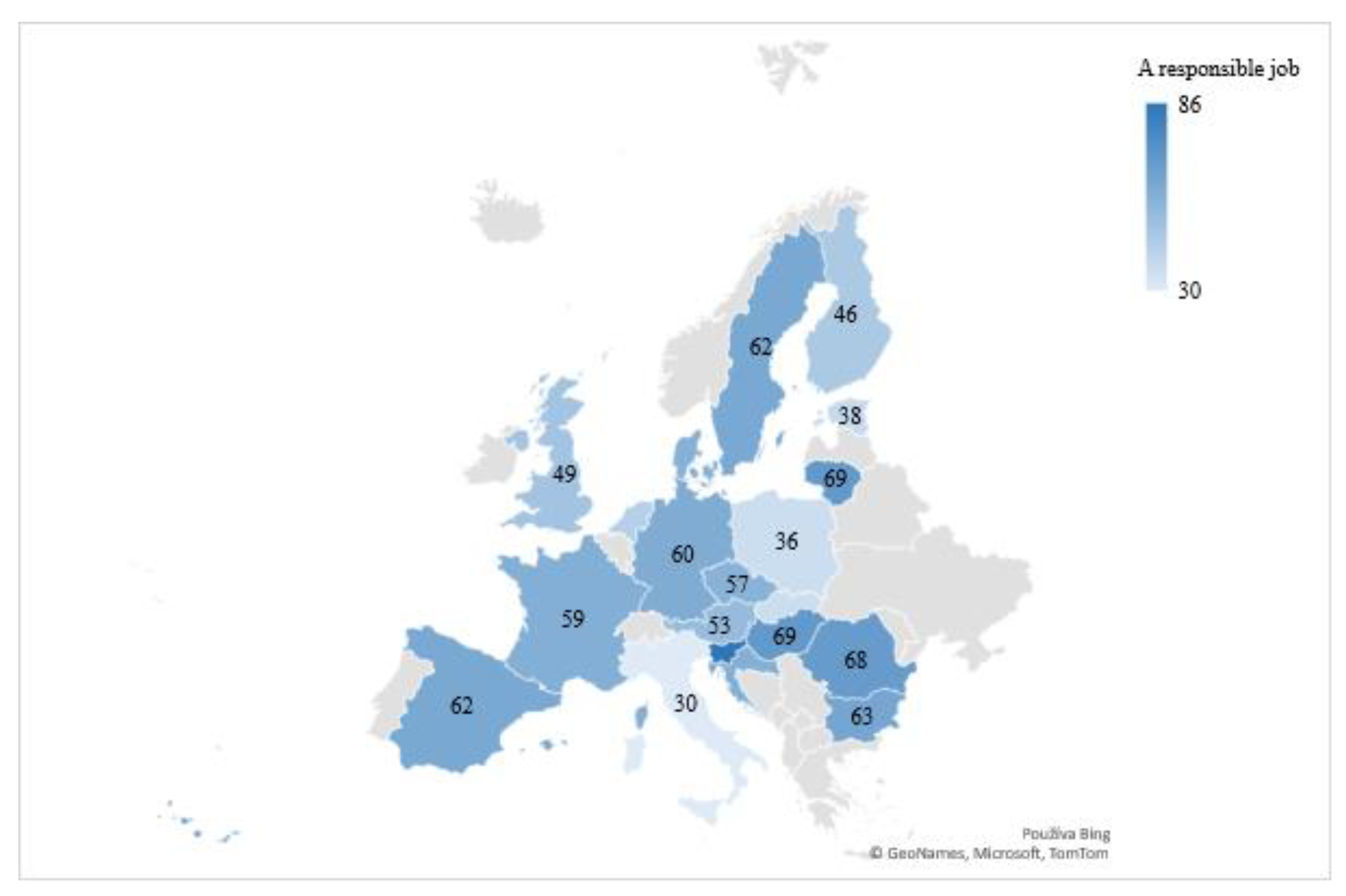

“Please say, for each of the following, how important it is in your life: work, family, friends and acquaintances, leisure time, politics and religion (options-very important, quite important, not important, not important at all)”.The percentage of those for whom the work is “very important” can be seen in

Figure 1. A look at the map of Europe shows us that work is most important for the people in Italy and Spain, where almost three-quarters of the population has identified this possibility. Work is essential for more than sixty percent in countries such as the Slovak Republic, Romania, Bulgaria, France, Poland and Sweden. In contrast, in Denmark and the Netherlands, just over a third of the population considers work to be very important. If we solely derive from the theory and studies applicable to the traditional gender stereotypes (e.g., A man should make money and a woman should take care of the household and children), work should be more important in the lives of men than women. However, looking at the results of EVS2017, the importance of working in the lives of individuals in most countries showed almost no difference between men and women, except for Italy, where the difference was 8 percentage points in favor of men, and Slovenia, where the difference was 10 percentage points in favor of women. This means that in most EU countries, work is important for both women and men. This is an important starting point for subsequent job attribute analyses, as it tells us that gender differences in job attributes preferences could be smaller than some studies suggest.

3.2. Job Attributes

The theoretical review of the literature lists a large number of attributes of the job in the preferences of which larger or smaller gender differences were observed within the individual research. In our work, we assume six attributes of work that were part of EVS research and were referred to by the following question:

“Here are a few things people use to judge jobs. Please look at them and please tell them which of them you personally consider important: (1) good pay, (2) good hours, (3) generous holidays, (4) an opportunity to use an initiative, (5) a job in which you feel you can achieve something, (6) a responsible job.”

We divided these six job attributes into external and internal attributes, and to better analyze the preferences of external and internal attributes, we created two indices (

Table 3):

3.3. External Job Attributes

According to most of the studies presented in this article, external attributes (excluding good pay) should be preferred by more women than men. Favorable external working conditions, such as favorable working hours and generous holidays, which represent a certain performance-providing performance, should enable women to better exercise their role as working mothers, which combines mothers and working women, and thus also helps them to cope better with the double load.

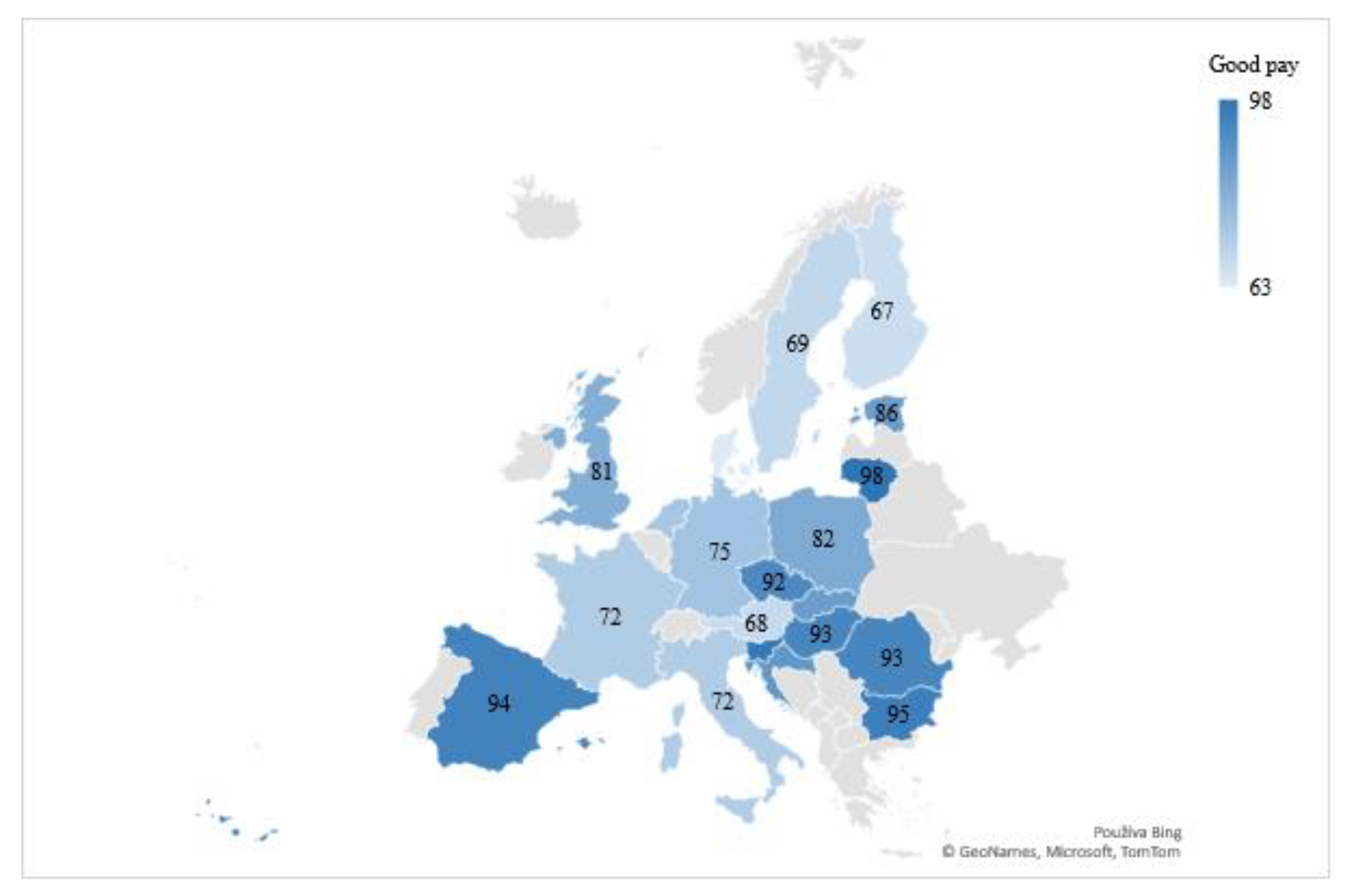

Regarding the preference of external job attributes within the compared countries, looking at

Figure 2, we see that the preference towards all three external attributes (at once) differs clearly between the compared European countries. External job attributes are most preferred by people in Lithuania, Romania, and Spain. On the contrary, they are the least important to the people of Italy and Poland. If we look at the differences between men and women, more significant gender differences in the preferences of external attributes were found only in the Slovak Republic, where the difference between men and women was 11 percentage points in favor of women.

Hypothesis 3a (H3a). There is no significant difference between the preference for external job attributes and the level of gender equality in EU countries.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b). There is a significant difference between the preference for external job attributes and the level of gender equality in EU countries.

Based on the results of the Chi-Square (see

Table 4) and the contingency coefficient (

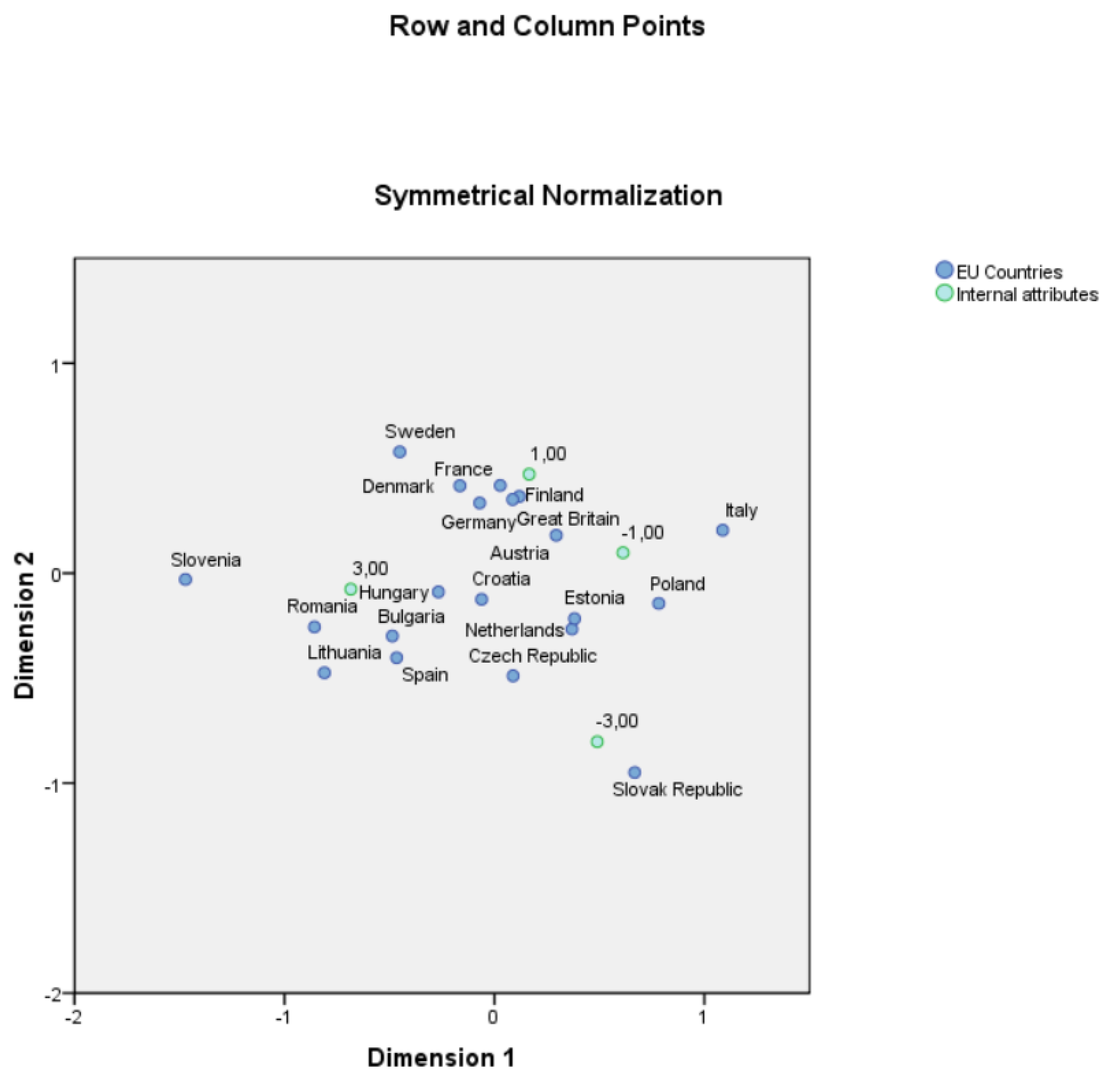

Table 5), we reject the null hypothesis H3a and accept the alternative hypothesis H3b, which speaks of the dependence between the level of gender equality and the preference for external attributes. The contingency coefficient is 0.360, which means that the dependence that exists between the two variables is medium. We reject the null hypothesis of variable independence based on the Chi-Square result, which means that it makes sense to further examine the internal structure of the resulting contingency table. The result of the correspondence analysis was four tables: a correspondence or contingency table, a summary table, and two tables containing the output of row and column profiles. Of these, we found that the first two dimensions contained enough information about row and column category correspondence. At the same time, we obtained a two-dimensional correspondence map, which contained two groups of points, one corresponding to row categories and the other to column categories (Correspondence Map 1, see

Figure 3).

To better understand the differences between the individual countries, a correspondence map is used, which is a visual reflection of the contingency table, and we can see in more detail the index of external job attributes. The index of external attributes combines good pay, advantageous working hours, and generous holiday. External attributes are most preferred in countries such as Lithuania, Bulgaria, Spain, Romania, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, and Hungary and, conversely, are least preferred by residents of France, Denmark, and Italy.

3.4. Good Pay

The first of the external attributes we examined is to have good pay. Good pay as such represents an instrumental goal or also material conditions representing characteristics, but we will work with it as an external job attribute in our work.

The possibility of having a good income is considered important in most of the EU countries under comparison. Despite some differences between countries, which can be seen in

Figure 4, these differences are the smallest, and it is true that having a good income is important for more than two-thirds of the population in each of the countries. Looking at

Figure 4, we can say that in countries with a higher level of gender equality, according to the EIGE Gender Equality Index (Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and France), good pay is less important for their population than in countries with lower levels of gender equality (Lithuania, Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary).

3.5. Good Hours

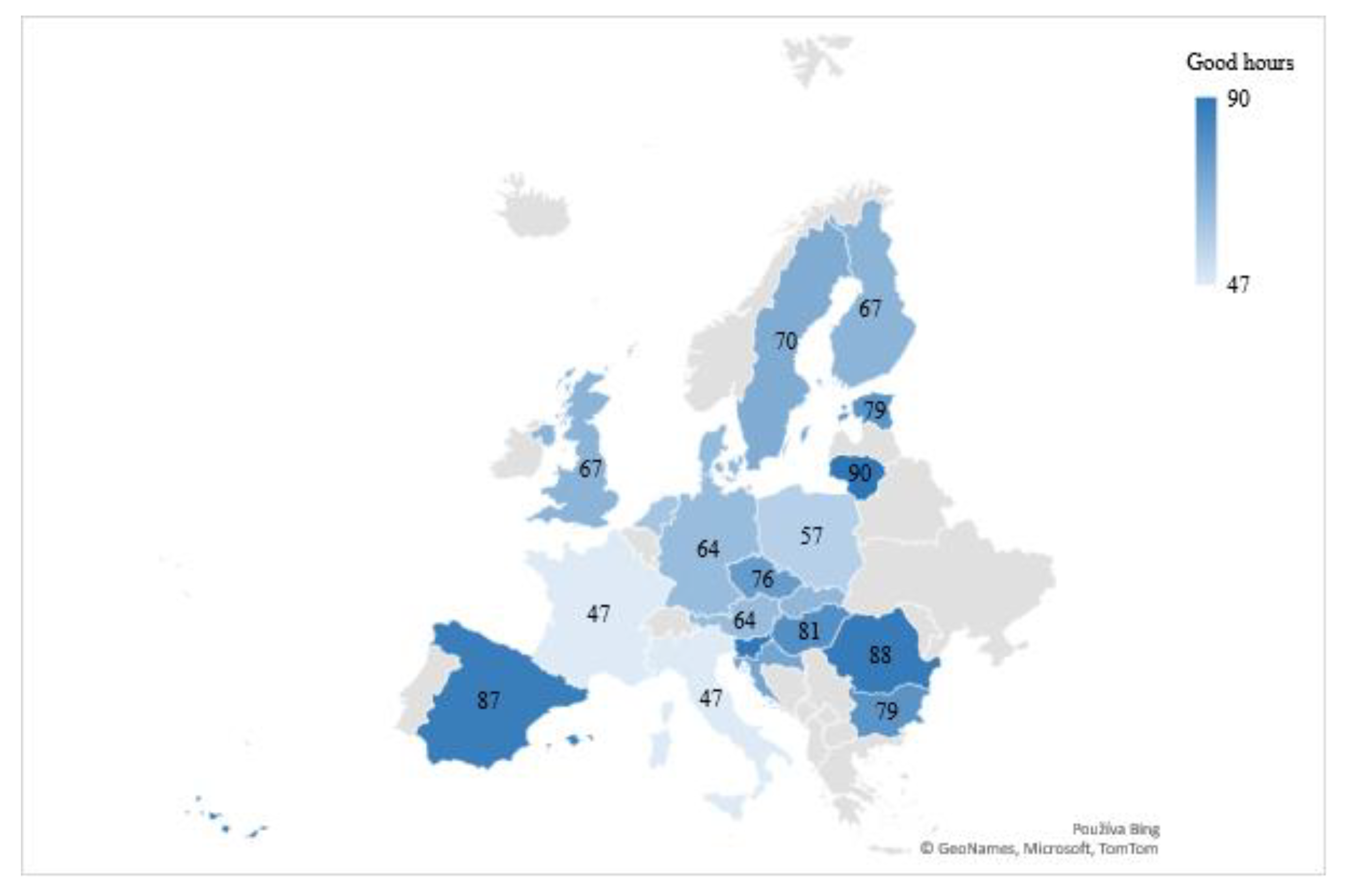

Favorable working time is the second of the external attributes. It should be more preferred by women because it indicates comfort at work, which should enable women to better combine their work responsibilities with those in the household.

In most of the countries, favorable working hours are important for more than two-thirds of the population (

Figure 5). The only exceptions are Italy and France, where just over half of the population (47%) consider it important. Regarding the comparison of the results of EVS2017 with the EIGE Gender Equality Index, the possibility of favorable working hours is important both in countries with a higher level of gender equality and in countries with a lower level of gender equality.

3.6. Generous Holidays

Generous holidays are the last of the external attributes, and like a good working day, it is an attribute focused on a certain comfort-providing destination.

As can be seen from

Figure 6, regarding external job attributes, there are the biggest differences between the EU countries for generous holidays. We could say that the need for generous holidays is more important for people in some Eastern European countries—notably Lithuania, Romania, and Bulgaria—which, according to the EIGE index, are countries with lower levels of gender equality-and Spain.

3.7. Internal Attributes

Internal attributes, as they represent a person who develops goals or also personal development supportive characteristics, should be more preferred by men, mainly because, according to the model of gender socialization, work as such should be more important for men than for women.

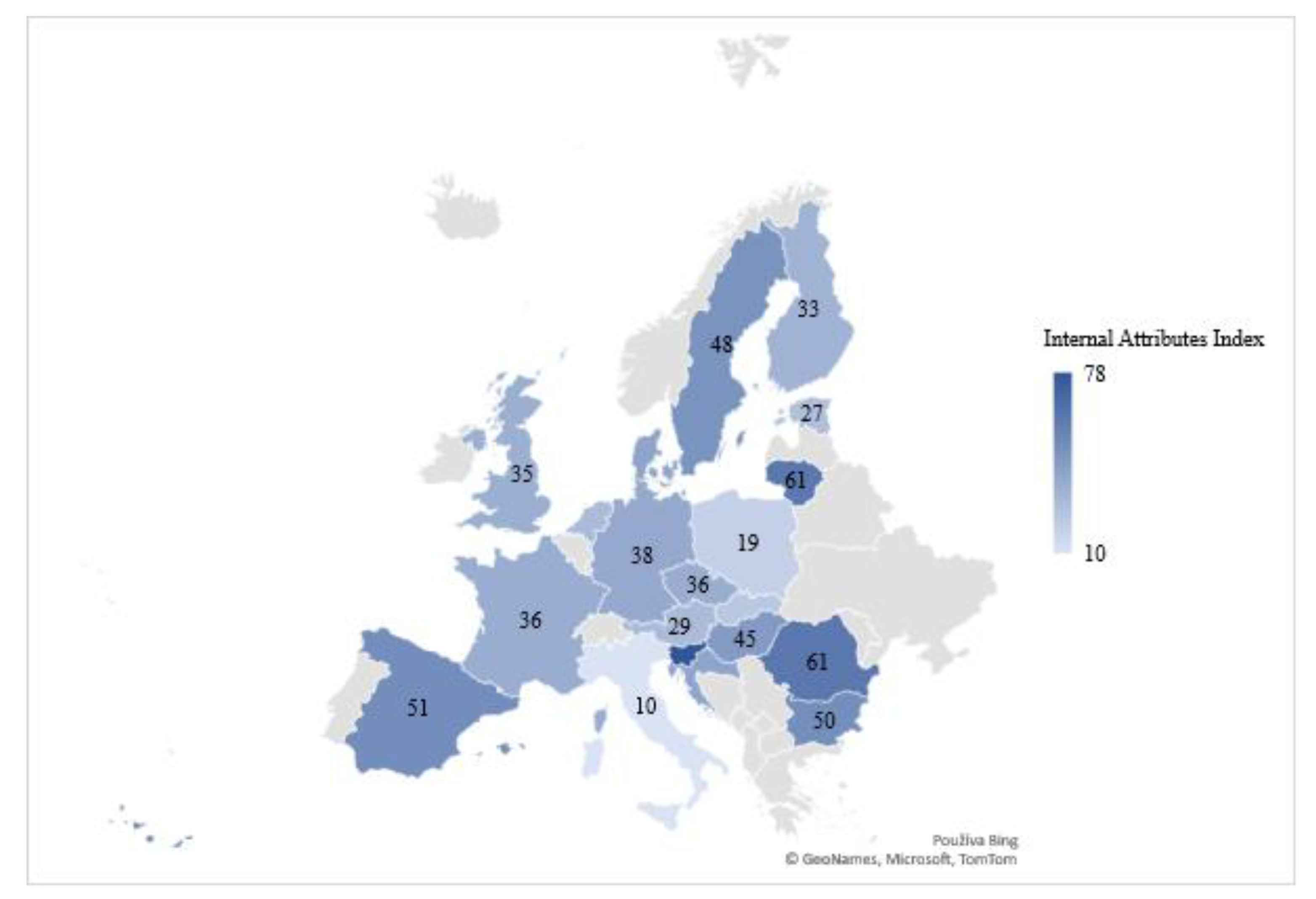

Regarding the preference for internal job attributes within the compared countries, a look at

Figure 7 shows us that the preference for all three internal attributes (at once) differs significantly between the European countries surveyed, although it is slightly less than the external attributes. They are most important for the population of Slovenia (78%) and the least for the population of Italy (10%). Significant gender differences in internal attribute preferences were not found in any of the countries.

Hypothesis 4a (H4a). There is no significant difference between the preference for internal job attributes and the level of gender equality in EU countries.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b). There is a significant difference between the preference for internal job attributes and the level of gender equality in EU countries.

Based on the results of the Chi-Square (

Table 6) and the contingency coefficient (

Table 7), we reject the null hypothesis H4a and accept the alternative hypothesis H4b, which speaks of the dependence between the level of gender equality and the preference for internal attributes.

The results of the chi-square mean the rejection of the null hypothesis of variable independence, and therefore, it makes sense to further investigate the internal structure of the resulting contingency table. We received four tables: correspondence or a contingency table, a summary table, and two tables containing the output of the row and column profiles, from which we found that the first two dimensions contained sufficient information about the correspondence of the row and column categories. Again, we obtained a two-dimensional correspondence map in which one group of points corresponded to the row category and the other group of points corresponded to the column categories (Correspondence Map 2, see

Figure 8).

The correspondence map visually shows us the preference for internal attributes, i.e., the index of internal attributes in individual states. The index of internal attributes combines personal initiative, the opportunity to achieve something, and a responsible job. We can say that the internal attributes were described as important for the job of the inhabitants of the Slovak Republic, especially for women, the least. The internal attributes were most important in countries such as Slovenia, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Lithuania.

3.8. An Opportunity to Use Initiative

Personal initiative as an internal attribute is a characteristic that largely supports the personal development of individuals.

Looking at

Figure 9, we see that European countries differ in how important it is for their people to take personal initiative at work. It is least important for the people of Italy and Poland, but the opportunity to take initiative is most appreciated in Slovenia, Romania, Lithuania, and Sweden. EVS2017 results on the internal attributes of the personal initiative show almost no parallel with the EIGE Gender Equality index.

3.9. A Job in Which You Feel You Can Achieve Something

A job in which you feel you can achieve something is the second internal attribute associated with personality development. Our analysis shows that it is the most important internal attribute.

This is a relatively highly valued attribute by the population in most of the countries being compared. A job in which you feel you can achieve something is, with the exception of the Slovak Republic (50%), important for more than sixty percent of the population of all countries.

Figure 10 even shows that in twelve countries, more than three-quarters of the population consider it possible to achieve something at work.

Although a job in which you feel you can achieve something is important for most countries, if we compare the results of EVS2017 and the EIGE Gender Equality Index, we can see that in countries with a higher level of gender equality (northern European countries), they prefer this attribute more than in countries with lower levels of gender equality.

3.10. Responsible Job

Although the responsible job, as the last of the internal attributes, is not classified by the authors as a personal-development-supporting characteristic, we classify it as an internal attribute.

From

Figure 11, it is clear that having a responsible job is the least valued internal attribute in the countries under comparison, except for the population of Slovenia (86%), while in Italy, Poland, and the Slovak Republic, only about one-third of the population considers the responsible jobs important.

The results of EVS2017 regarding the internal attributes of a responsible job, as with the possibility of taking a personal initiative, show almost no parallel with the EIGE Gender Equality Index.

4. Discussions

Is work a more important value of life for men than for women? A large number of relevant studies and research state that men and women differ in terms of their preference for individual job attributes, and one of the reasons is that work is of varying vital value [

35,

36,

37]. Men have been raised since childhood as future breadwinners, one of the key roles of which is to provide for their families financially, which is also related to the fact that work should be a key value for them [

33,

38]. However, EVS2017 research shows that work is as important of a value for women as it is for men in almost all EU countries-there were only significant differences between men and women in Italy and Slovenia. Therefore, the possible existence of gender differences in the preferences of job attributes will have other causes [

39].

In which EU countries are external job attributes more preferred, and in which internal ones? External job attributes represent tangible things and are external to the individual in their sense because they are not related to how a person does their job or its content [

27]. External job attributes are most preferred by people in Lithuania, Romania, and Spain. Internal attributes are a mirror image of external ones and represent personality-developing goals or personal-development-supporting characteristics. They were most important in Eastern European countries such as Slovenia, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary and Lithuania. With the extended attributes, we do not see the division of European states into western and eastern.

However, a thorough quantitative analysis of data from the European Values Study (EVS2017) showed us different conclusions from those presented in the theoretical part. In almost all EU countries, work as a value of life was as important for women as it was for men. As for the attributes of the job, gender differences confirmed that the attribute “favorable working hours” is more important for women in almost three-quarters of the EU countries. However, in the other analyzed job attributes, we did not find significant gender differences in their preferences. We have not identified that good pay is more important to men nor that internal personality-developing attributes are more preferred by men. This may contradict the traditional gender stereotype measured in recent empirical studies researching gender discrimination at work [

40,

41].

On the contrary, the two internal attributes of “achievable job” and “responsible job” have shown us in more than a quarter of the EU countries that women are more likely to choose these attributes. This fact contradicts the claims and conclusions of the above-mentioned studies regarding gender differences in job attribute preferences, as these studies attach more importance to internal personality-developing attributes to men rather than women. However, these results are in line with our previous findings on the importance of work as a value of life, which states that work is as important for women as for men in most EU countries. These findings are also in line with previous research from a cross-national perspective [

18].

In which EU countries are gender stereotypes the greatest? The inclination towards gender stereotypes differs slightly depending on which stereotype it is. The first stereotype concerning the traditional gender role of women has the greatest support in countries such as Austria, Italy, and Hungary. The second stereotype, representing the traditional gender stereotype regarding gender roles of men and women, has the most supporters in Bulgaria, Romania, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. The third stereotype, mapping attitudes regarding the ascriptive roles of women or segregation of gender roles at the social level, has the greatest support in the countries of Eastern Europe-in Romania, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, but especially in the Slovak Republic. In contrast, the least support for all three gender stereotypes is in northern European countries and some western European countries. A recent comparative study of 24 EU member states indicates that greater feminization of employment is also related to greater payment gaps [

42].

What is the attitude of the people of the EU to the gender division of male and female roles at the societal level? The traditional division of gender roles is the result of gender socialization, which reinforces gender stereotypes in society. Based on our analysis of the EVS2017 research, we observe large differences within the EU countries. On the one hand, there are northern and western Europe, and on the other hand, there are the states of Eastern Europe. We can state that the inhabitants of the countries with the highest levels of gender equality, such as Sweden, Denmark, and Finland, overwhelmingly disagree with the claims that they attribute women a lesser role in the performance of certain social functions. We observe a similar fact in the countries of Western Europe, which are also characterized by a higher level of gender equality.

5. Conclusions

We assumed that variables such as the number of children and their age (the age of the youngest person in the household) would be reflected in the gender-different preference for job attributes. However, in the attribute where we found the biggest gender differences, namely “favorable working hours”, the facts about children did not play a significant role for women. On the contrary, the age of children was a more significant variable for men.

Gender was not a significant attribute for the “good earnings” attribute, but the key variable was age in several EU countries; as the age category increased, so did the likelihood of good earnings. For the option “long vacation” as an attribute important for work, the key variable increasing the probability of choice was the value of leisure time in the lives of individuals. This means that leisure time was more important than the gender of individuals, thus of great importance in their lives.

Educational attainment has proven to be key in several countries with two internal attributes: “opportunities for personal initiative” and “job in which something can be achieved” both for men and women. Our finding is that in the EU countries, educational attainment is much more important for their preference as well as a job as a value of life than gender.

Comparing the results of our analysis of job attributes with the EIGE Gender Equality Index leads us to the conclusion that the level of gender equality is not significantly reflected in the preference towards job attributes or in the gender differences in their preferences. The level of gender equality in EU countries is not a variable that would affect the preference for job attributes.

However, our research results are not without limitations. First, we captured and measured only selected aspects of attributes of paid job preferences between men and women. We only tested two central hypotheses for internal and external attributes’ preference. Our data do not capture the volatility present in changing patterns of an individual´s preferences, life trajectories, and other external factors. Therefore, we cannot generalize our findings only relate them to the available up-to-date literature review. On the other hand, we tried to capture the ongoing gender stereotypes and work–life balance in particular aspects of paid job attributes preference from the latest wave of EVS surveys.

We assumed we would find a parallel between the inclination towards gender stereotypes regarding the traditional gender division of roles between men and women and the level of gender equality according to EIGE. This assumption has been confirmed, and, according to the results of our analysis presented in the discussions above, the parallel is really significant, with the people of Eastern and Southern Europe representing the lowest level of gender equality inclined toward the traditional division of gender roles between men and women. We can thus say that the degree of inclination towards gender stereotypes depends directly on the level of gender equality in a given EU country.