Aesthetics of Sustainability: Research on the Design Strategies for Emotionally Durable Visual Communication Design

Abstract

:1. Introduction

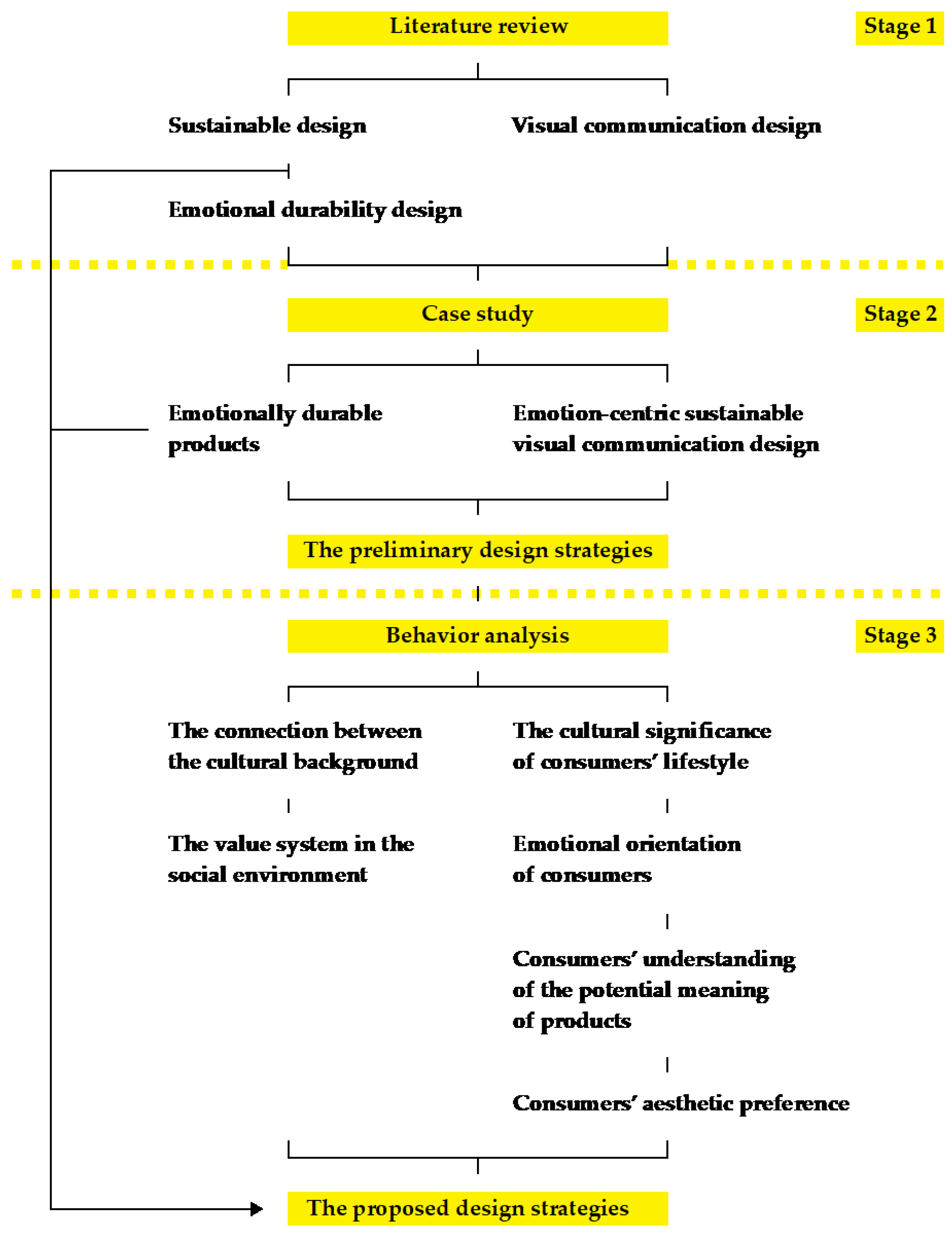

2. Methodology

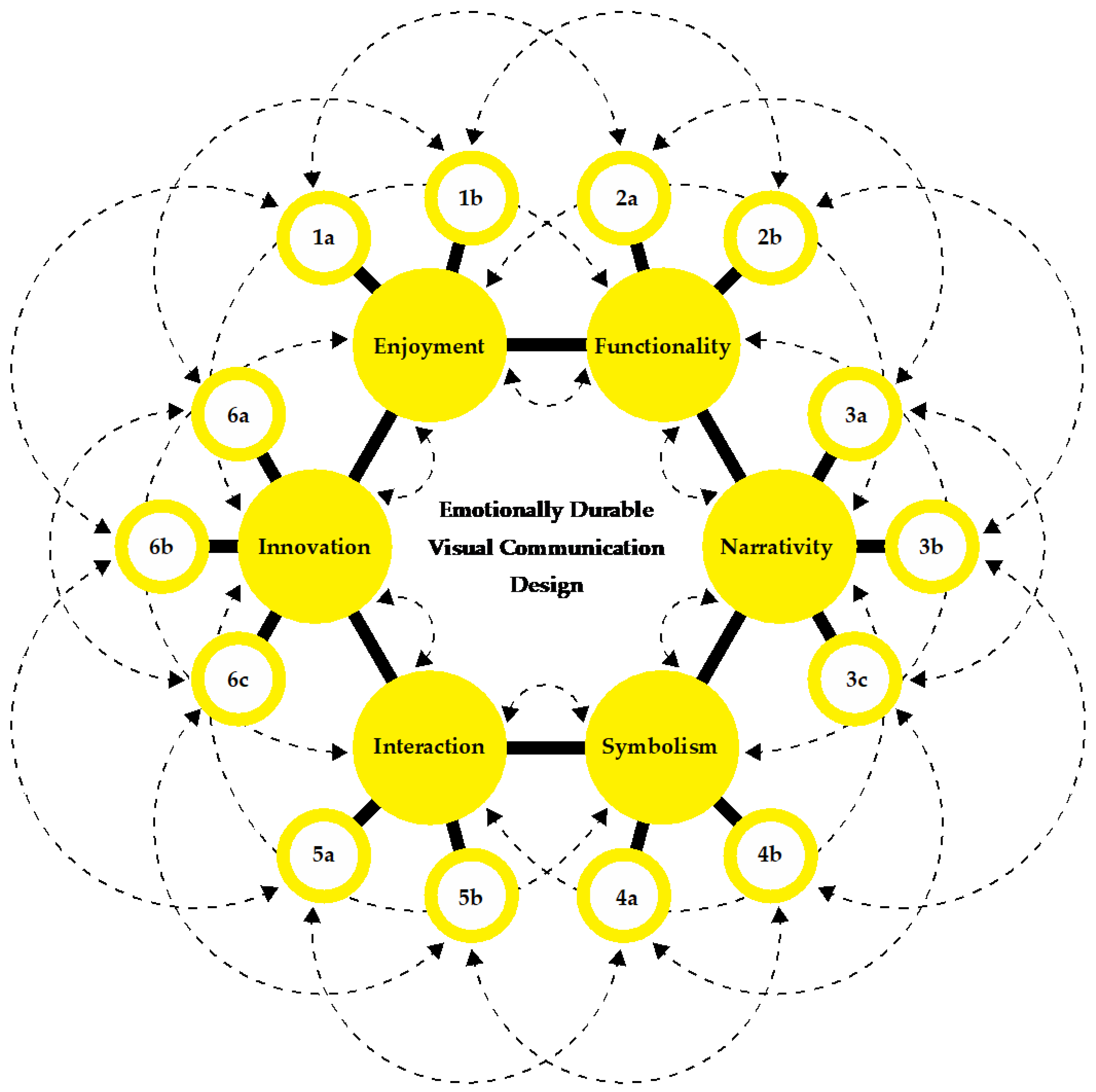

3. Establishment of Design Strategies

3.1. Enjoyment

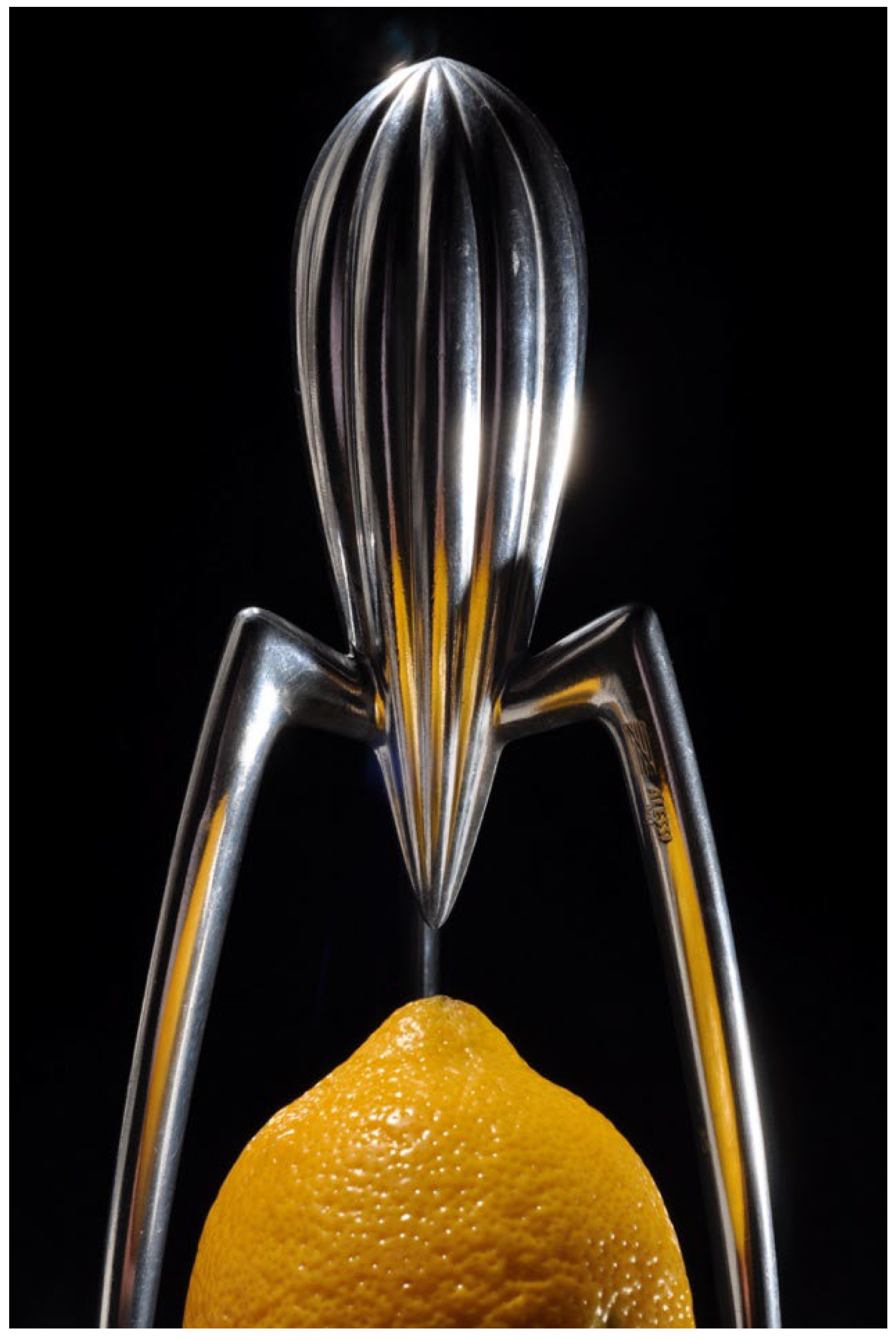

3.2. Functionality

3.3. Narrativity

3.4. Symbolism

3.5. Interaction

3.6. Innovation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeBell, M.; Dardis, R. Extending product life: Technology isn’t the only issue. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1979, 6, 381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nes, N.; Cramer, J. Influencing product lifetime through product design. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2005, 14, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T. Inadequate life? Evidence of consumer attitudes to product obsolescence. J. Consum. Policy 2004, 27, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schifferstein, H.N.; Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, E.P. Consumer-product attachment: Measurement and design implications. Int. J. Des. 2008, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Papanek, V. Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change; Van Nostrand Reinhold Co: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Highmore, B. The Design Culture Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, D. Green Design: Design for the Environment; Laurence King: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Burall, P. Green Design; The Design Council: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Madge, P. Ecological design: A new critique. Des. Issues 1997, 13, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boks, C.; McAloone, T.C. Transitions in sustainable product design research. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2009, 9, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binswanger, M. Technological progress and sustainable development: What about the rebound effect? Ecol. Econ. 2001, 36, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziulusoy, A.I. A critical review of approaches available for design and innovation teams through the perspective of sustainability science and system innovation theories. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamra, T.; Lilley, D.; Tang, T. Design for sustainable behaviour: Using products to change consumer behaviour. Des. J. 2011, 14, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynning, M. Visual Communication and Speculations: Designing transitions towards a more sustainable future. In Proceedings of the Expanding Communities of Sustainable Practice: 15 October 2016: Symposium Proceedings, Leeds, UK, 15 October 2016; pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. The Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://undocs.org/A/RES/71/313 (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Tang, T.; Bhamra, T. Improving energy efficiency of product use: An exploration of environmental impacts of household cold appliance usage patterns. In Proceedings of the The 5th International Conference on Energy Efficiency in Domestic Appliances and Lighting EEDAL, Berlin, Germany, 16–18 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, E.; Boks, C. How design of products affects user behaviour and vice versa: The environmental implications. In Proceedings of the 2005 4th International Symposium on Environmentally Conscious Design and Inverse Manufacturing, Tokyo, Japan, 12–14 December 2005; pp. 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lockton, D.; Harrison, D.; Stanton, N.A. The Design with Intent Method: A design tool for influencing user behaviour. Appl. Ergon. 2010, 41, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Irizar-Arrieta, A.; Casado-Mansilla, D.; Garaizar, P.; López-de-Ipiña, D.; Retegi, A. User perspectives in the design of interactive everyday objects for sustainable behaviour. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2020, 137, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wever, R.; Van Kuijk, J.; Boks, C. User-centred design for sustainable behaviour. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2008, 1, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludden, G.D.S.; Offringa, M. Triggers in the environment. Increasing reach of Behavior Change Support Systems by connecting to the offline world. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Behavior Change Support Systems, BCSS 2015, Chicago, IL, USA, 3 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ceschin, F.; Gaziulusoy, I. Evolution of design for sustainability: From product design to design for system innovations and transitions. Des. Stud. 2016, 47, 118–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, G.; Kosoris, J.; Hong, L.N.; Crul, M. Design for sustainability: Current trends in sustainable product design and development. Sustainability 2009, 1, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, A. Psychologically Durable Design–Definitions and Approaches. Des. J. 2019, 22, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S. Object lessons: Enduring artifacts and sustainable solutions. Des. Issues 2006, 22, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugge, R.; Schifferstein, H.N.; Schoormans, J.P. Product attachment and satisfaction: Understanding consumers’ post-purchase behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J. Emotionally Durable Design: Objects, Experiences and Empathy, 1st ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, J. Emotionally Durable Design: Objects, Experiences and Empathy, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chick, A.; Micklethwaite, P. Design for Sustainable Change: How Design and Designers Can Drive the Sustainability Agenda; AVA Publishing SA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, C. The cultural influence of brands: In defense of advertising. In Citiz. Des. Perspect. Des. Responsib; Allworth Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of brand personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Streimikiene, D.; Berchtold, G.; Vveinhardt, J.; Channar, Z.A.; Soomro, R.H. Effectiveness of online digital media advertising as a strategic tool for building brand sustainability: Evidence from FMCGs and services sectors of Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishaq, M.I.; Di Maria, E. Sustainability countenance in brand equity: A critical review and future research directions. J. Brand Manag. 2020, 27, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.; Sharma, M. Antecedents and outcomes of brand strength: A study of Asian IT organizations towards brand sustainability. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2021, 24, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boz, Z.; Korhonen, V.; Koelsch Sand, C. Consumer considerations for the implementation of sustainable packaging: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steenis, N.D.; van Herpen, E.; van der Lans, I.A.; Ligthart, T.N.; van Trijp, H.C. Consumer response to packaging design: The role of packaging materials and graphics in sustainability perceptions and product evaluations. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaiman, K.; Ortega, D.L.; Garnache, C. Consumer preferences and demand for packaging material and recyclability. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 115, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koeijer, B.; De Lange, J.; Wever, R. Desired, perceived, and achieved sustainability: Trade-offs in strategic and operational packaging development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tacker, M. Methods for the assessment of environmental sustainability of packaging: A review. IJRDO 2017, 3, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Dobon, A.; Cordero, P.; Kreft, F.; Østergaard, S.R.; Antvorskov, H.; Robertsson, M.; Smolander, M.; Hortal, M. The sustainability of communicative packaging concepts in the food supply chain. A case study: Part 2. Life cycle costing and sustainability assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2011, 16, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindh, H.; Olsson, A.; Williams, H. Consumer perceptions of food packaging: Contributing to or counteracting environmentally sustainable development? Packag. Technol. Sci. 2016, 29, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borgman, I. The Influence of Packaging Design Features on Consumers’ Purchasing & Recycling Behaviour. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haines-Gadd, M.; Chapman, J.; Lloyd, P.; Mason, J.; Aliakseyeu, D. Emotional durability design nine—A tool for product longevity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonagh, D.C.; Hekkert, P.; Van Erp, J.; Gyi, D. Design and Emotion: The Experience of Everyday Things; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, A.G.; Michael Siu, K.W. Explore the Role of Emotion in Design: Empirical Study to Understand the Perception on Emotion Design, Emotional Design, Emotionalise Design from the Designers’ Perspectives. Des. Princ. Pract. Int. J. 2011, 5, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornquist, C. Unemotional design: An alternative approach to sustainable design. Des. Issues 2017, 33, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P.M.; Hekkert, P. Special issue editorial: Design & emotion. Int. J. Des. 2009, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Halton, E. The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, A.G. Analysis of emotion and cultural background on affective design process. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 17–21 July 2017; pp. 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Van Krieken, B.; Desmet, P.; Aliakseyeu, D.; Mason, J. A sneaky kettle: Emotionally durable design explored in practice. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Design and Emotion, London, UK, 11–14 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Richins, M.L. Special possessions and the expression of material values. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, S.S.; Kleine, R.E., III; Allen, C.T. How is a possession “me” or “not me”? Characterizing types and an antecedent of material possession attachment. J. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J.P.; Schifferstein, H.N. Design strategies to postpone consumers’ product replacement: The value of a strong person-product relationship. Des. J. 2005, 8, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlizzi, J.; Disalvo, C.; Hanington, B. On the relationship between emotion, experience and the design of new products. Des. J. 2003, 6, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padró, M. Emotionally Durable Lighting: An Exploration of Emotionally Durable Design for the Lighting Domain. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P.W. Designing Pleasurable Products: An Introduction to the New Human Factors; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre and Every Business a Stage, 2nd ed.; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, R. The Dream Society: How the Coming Shift from Information to Imagination Will Transform Your Business; Mc Graw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Johar, J. Toward an integrated model of self-congruity and functional congruity. ACR Eur. Adv. 1999, 4, 252–256. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, M.R. Deep-seated materialism: The case of Levi’ s 501 jeans. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1986, 13, 619–622. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, A.; Goworek, H. Investigating the relationship between consumer attitudes and sustainable fashion product development. In Sustainability in Fashion; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, M.; White, E.J.; McMahon, M.; O’Sullivan, L.W. Using personas to exploit environmental attitudes and behaviour in sustainable product design. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 78, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.G.; Siu, K.W.M.G. Emotion design, emotional design, emotionalize design: A review on their relationships from a new perspective. Des. J. 2012, 15, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Durability, fashion, sustainability: The processes and practices of use. Fash. Pract. 2012, 4, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcikova, M. Mundane fashion: Women, clothes and emotional durability. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Art, Design and Architecture, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, K.; Cao, Y.; Girouard, A.; Loke, L. Breathing Scarf: Using a First-Person Research Method to Design a Wearable for Emotional Regulation. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Daejeon, Korea, 13–16 February 2022; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S. After taste—The power and prejudice of product appearance. Des. J. 2009, 12, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agost, M.-J.; Vergara, M. Principles of Affective Design in Consumers’ Response to Sustainability Design Strategies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jin, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Dong, X. Emotionally Sustainable Design Toolbox: A Card-Based Design Tool for Designing Products with an Extended Life Based on the User’s Emotional Needs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.; Engström, H. Design for Prolonged Service Lifetime: A Case Study of Built-In Ovens Implementing Emotionally Durable Design in Practice. Master’s Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.-L.; Chen, S.-C.; Lin, H.; Cheng, Y.-Y. Emotional design evaluation index and appraisal a study on design practice. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Orlando, FL, USA, 26–31 July 2019; pp. 450–462. [Google Scholar]

- Seva, R.R. Product-behavior targeting: Affective design method for sustainability. In Proceedings of the International MultiConference of Engineers and Computer Scientists, Hong Kong, China, 13–15 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cupchik, G.C. Emotion and industrial design: Reconciling meanings and feelings. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Design and Emotion, Delft, The Netherlands, 3–5 November 1999; pp. 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, D.; Bruseberg, A.; Haslam, C. Visual product evaluation: Exploring users’ emotional relationships with products. Appl. Ergon. 2002, 33, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimäki, K.; Koskinen, I. I love this dress, it makes me feel beautiful! Empathic knowledge in sustainable design. Des. J. 2011, 14, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J. Designing Meaningful & Lasting User Experiences. In Love Objects: Emotion, Design & Material Culture; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2014; pp. 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, J. Design for (emotional) durability. Des. Issues 2009, 25, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tseng, Y.-S.; Ho, M.-C. Designing the personalized nostalgic emotion value of a product. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Design, User Experience, and Usability, Orlando, FL, USA, 9–14 July 2011; pp. 664–672. [Google Scholar]

- Fossdal, M.; Berg, A. The relationship between user and product: Durable design through personalisation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, Aalborg, Denmark, 8–9 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva, M.; Ayanoğlu, H. Emotions and emotions in design. In Emotional Design in Human-Robot Interaction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley, N. Design history or design studies? Des. Issues 1995, 11, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, A.D.; Tasaki, L.H. The role and measurement of attachment in consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 1992, 1, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelinger, E. Extension and structure of the self. J. Psychol. 1959, 47, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, D.C. Personality; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the Extended Self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenwald, A.G. A social-cognitive account of the self’s development. In Self, Ego, and Identity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; pp. 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, A.S. The Scenario of SensoryEncounter: Cultural Factorsin Sensory—AestheticExperience. In Pleasure with Products: Beyond Usability; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2002; pp. 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Schifferstein, H.N.; Mugge, R.; Hekkert, P. Designing consumer-product attachment. In Design and Emotion; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2004; pp. 327–331. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.S.; Holbrook, M.B.; Solomon, M.R. Combining esthetic and social value to explain preferences for product styles with the incorporation of personality and ensemble effects. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 1991, 6, 243. [Google Scholar]

- Veryzer Jr, R.W.; Hutchinson, J.W. The influence of unity and prototypicality on aesthetic responses to new product designs. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 374–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludden, G.D.S. Sensory Incongruity and Surprise in Product Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhamme, J.; Snelders, D. What if you surprise your customers… Will they be more satisfied? Findings from a pilot experiment. ACR N. Am. Adv. 2003, 30, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, C.A.; Den Hollander, M.; Van Hinte, E.; Zijlstra, Y. Products that Last: Product Design for Circular Business Models; TU Delft Library: Delft, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, A. Sustainable Users and the World of Objects Design and Consumerism. In Eternally Yours: Time Design, Product, Value, Sustenance; Van Hinte, E., Ed.; 010 Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 10, pp. 102–131. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nes, N. Understanding replacement behaviour and exploring design solutions. In Longer Lasting Products; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 133–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, S. Veillance Integrity by Design: A new mantra for CE devices and services. [Soapbox]. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2015, 5, 33–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugge, R. Product Attachment. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hinte, E. Eternally Yours: Visions on Product Endurance; 010 Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Casais, M.; Mugge, R.; Desmet, P.M. Using symbolic meaning as a means to design for happiness: The development of a card set for designers. In Proceedings of the 50th Anniversary Conference on Design Research Society (DRS 2016), Brighton, UK, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolás, J.C.O.; Aurisicchio, M.; Desmet, P.M. Pleasantness and arousal in twenty-five positive emotions elicited by durable products. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Design & Emotion, Bogotá, Colombia, 6–10 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Battarbee, K.; Mattelmaki, T. Meaningful product relationships. In Design and Emotion; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; pp. 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Maclachlan, M. Emotional Design Strategies to Enhance User Experience and Encourage Product Attachment. Ph.D. Thesis, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, Scotland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mugge, R.; Schifferstein, H.N.; Schoormans, J.P. Personalizing product appearance: The effect on product attachment. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Design and Emotion, Ankara, Turkey, 12–14 July 2004; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Battarbee, K.; Koskinen, I. Co-experience: Product experience as social interaction. In Product Experience; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 461–476. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, R.; Belk, R.W. Artifacts, identity, and transition: Favorite possessions of Indians and Indian immigrants to the United States. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patlar, D.; Kurtgözü, A. Questioning the validity of emotion in design: A critical examination of the multi-faceted conditions of its historical emergence. In Design and Emotion; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; p. 469. [Google Scholar]

- Grosse-Hering, B. Slow Design. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Philips Corporate Design. Guidelines for Ecological Design; Philips Corporate Design: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, O.V. Fashion-Able. Hacktivism and Engaged Fashion Design. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Design and Crafts, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan, H.; Archer-Martin, J.; Menzies, G.; Bailey, J.; Kane, K.; Fox Derwin, E. Make/Use: A system for open source, user-modifiable, zero waste fashion practice. Fash. Pract. 2018, 10, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, M.I.; Mochon, D.; Ariely, D. The IKEA effect: When labor leads to love. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSalvo, C.; Hanington, B.; Forlizzi, J. An accessible framework of emotional experiences for new product conception. In Design and Emotion; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2004; pp. 256–287. [Google Scholar]

- Laitala, K.M.; Boks, C.; Klepp, I.G. Making clothing last: A design approach for reducing the environmental impacts. Int. J. Des. 2015, 9, 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, L. Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers; Imperfect Publishing: Point Reyes, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Keulemans, G. The geo-cultural conditions of kintsugi. J. Mod. Craft 2016, 9, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, P.M.; Hekkert, P. The basis of product emotions. In Pleasure with Products Beyond Usability; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2002; pp. 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- MacInnis, D.J.; Price, L.L. The role of imagery in information processing: Review and extensions. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E. Design, Environment and Social Quality: From “Existenzminimum” to “Quality Maximum”. Des. Issues 1994, 10, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Second White. Humidifier H5. Available online: https://www.behance.net/gallery/86469467/Humidifier-H5?tracking_source=search_projects%7CEmotional%20Design (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Austin, E.L.; Hauser, O. The Sesqui-Centennial International Exposition: A Record Based on Official Data and Departmental Reports; Current Publications: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Great Exhibition London, Great Britain—Commissioners for the Exhibition of 1851. In Reports by the Juries on the Subjects in the Thirty Classes into which the Exhibition Was Divided: Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851; Spicer Brothers: London, UK, 1852; Volume II.

- Wyatt, S.M.D. A Report on the Eleventh French Exposition of the Products of Industry; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1849. [Google Scholar]

- Purbrick, L. “I love giving presents”: The emotion of material culture. In Love Objects: Emotion, Design and Material Culture; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2014; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- M&C Saatch. H&T Pawnbrokers Fuses Vintage and Modern to Spotlight Pre-Loved Jewellery in Festive Campaign. Available online: https://marcommnews.com/ht-pawnbrokers-fuses-vintage-and-modern-to-spotlight-pre-loved-jewellery-in-festive-campaign-from-mc-saatchi/ (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Chen, J.C.-C. The impact of nostalgic emotions on consumer satisfaction with packaging design. J. Bus. Retail Manag. Res. 2014, 8, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujan, M.; Bettman, J.R.; Baumgartner, H. Influencing consumer judgments using autobiographical memories: A self-referencing perspective. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, K.A.; Ellis, R.; Loftus, E.F. Make my memory: How advertising can change our memories of the past. Psychol. Mark. 2002, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlena, W.J.; Holak, S.L. “The Good Old Days”: Observations on Nostalgia and Its Role in Consumer Behavior. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1991, 18, 323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Holak, S.L.; Havlena, W.J. Feelings, fantasies, and memories: An examination of the emotional components of nostalgia. J. Bus. Res. 1998, 42, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R. A review of nostalgic marketing. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2015, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swan, T. Behind the Wheel/Mini Cooper; Animated Short, Dubbed in German (2 June 2002, Section 12, p.1). Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2002/06/02/automobiles/behind-the-wheel-mini-cooper-animated-short-dubbed-in-german.html (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Wood, B.L. Stain. Available online: http://www.bethanlaurawood.com/work/stain/ (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Wang, C.H. GOGO Lamp. Available online: https://www.behance.net/gallery/37780835/GOGO-Lamp (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Beirut, M.; Drenttel, W.; Heller, S. Looking Closer 5: Critical Writings on Graphic Design; Allworth Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, A.; Kupferschmid, I. Helvetica Forever: Story of a Typeface; Lars Muller Publishers: Zurich, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schifferstein, H.N.; Spence, C. Multisensory product experience. In Product Experience; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 133–161. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L. Pig Line Ball. Available online: https://www.behance.net/gallery/73141865/Pig-line-ballv (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J.P.; Schifferstein, H.N. Product attachment: Design strategies to stimulate the emotional bonding to products. In Product Experience; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 425–440. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, N.; Piller, F. Value creation by toolkits for user innovation and design: The case of the watch market. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2004, 21, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swatch X You. Available online: https://www.swatch.com/en-us/swatch-x-you.html (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Randall, T.; Terwiesch, C.; Ulrich, K.T. Principles for user design of customized products. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2005, 47, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dahl, D.W.; Moreau, C.P. Thinking inside the box: Why consumers enjoy constrained creative experiences. J. Mark. Res. 2007, 44, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, C.; Kahn, B.E. Variety for sale: Mass customization or mass confusion? J. Retail. 1998, 74, 491–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.M. News of the Wooled Introduction to Knitting. Available online: https://www.behance.net/gallery/25761295/News-of-the-Wooled-Introduction-to-Knitting (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Lee, H. The Jingle Bank. Available online: https://www.behance.net/gallery/23395323/Jingle-Bank (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Stäubli, N.E. Foldschool. Available online: https://www.nicola-staubli.com/foldschool/ (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Goldstein, E.B. Sensation and Perception, 6th ed.; Wadsworth Publications: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Design Strategies | Supplements | Design Cases |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Enjoyment [4,26,49,58,71,73,74,90] | 1a. Indicates the pleasure of the product in use [4,68,90,91,92,93]. |

|

| 1b. Provide consumers with interesting and unexpected interactions and discoveries during use [29,71,72,74,94,95]. |

| |

| 2. Functionality [4,26,27,49,71] | 2a. Show the practical functions of products and reflect their reliable quality [4,49,52,71,96,97,98]. |

|

| 2b. Show products’ real and specific functions [29,30,45,49,98,99]. |

| |

| 3. Narrativity [4,30,45,71,73] | 3a. Show that products can be used as gifts for holidays, anniversaries, and other special days [4,30,45,54,73,74,100]. |

|

| 3b. Create a nostalgic or retro feeling with a visual image that can reflect the past [52,71,81,101,102]. |

| |

| 3c. Tell an interesting and continuous story [29,45,52,72,81,103]. |

| |

| 4. Symbolism [26,27,52,104] | 4a. Symbolize personal or social identities that consumers expect, and promote consumers’ self-identification or a sense of belonging to their social groups [4,26,27,52,53,54,58,68,71,73,100,105,106,107]. |

|

| 4b. Embody the symbolism of cultural value [26,27,73,74,108,109]. |

| |

| 5. Interaction [45,49,52] | 5a. Create interesting interactions between consumers and products and between consumers [29,45,49]. |

|

| 5b. Enable consumers to reflect interactivity by assigning products with personality [29,45,52,57,70,110,111,112,113]. |

| |

| 6. Innovation [67,74] | 6a. Create new usage routines, rituals, and experiences for products (or services), and modify some attributes of products specifically or symbolically [45,110,114,115]. |

|

| 6b. Create more uses for the products without additional components [45,55,78,98,100,116]. |

| |

| 6c. Leave room for design innovation [29,45,117,118]. |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, S.; Lin, P.-S. Aesthetics of Sustainability: Research on the Design Strategies for Emotionally Durable Visual Communication Design. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084649

Ji S, Lin P-S. Aesthetics of Sustainability: Research on the Design Strategies for Emotionally Durable Visual Communication Design. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084649

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Shaorong, and Pang-Soong Lin. 2022. "Aesthetics of Sustainability: Research on the Design Strategies for Emotionally Durable Visual Communication Design" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084649

APA StyleJi, S., & Lin, P.-S. (2022). Aesthetics of Sustainability: Research on the Design Strategies for Emotionally Durable Visual Communication Design. Sustainability, 14(8), 4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084649