A Multicriteria Methodology to Evaluate Climate Neutrality Claims—A Case Study with Spanish Firms

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Existing Climate Neutrality Frameworks

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology

- -

- Criteria: the main elements that must be considered when evaluating climate neutrality issues;

- -

- Sub-criteria: specific aspects to be addressed within each criterion;

- -

- Question: the issue against which scores are given. There is one question per sub-criteria.

3.2. Case Study

4. Results

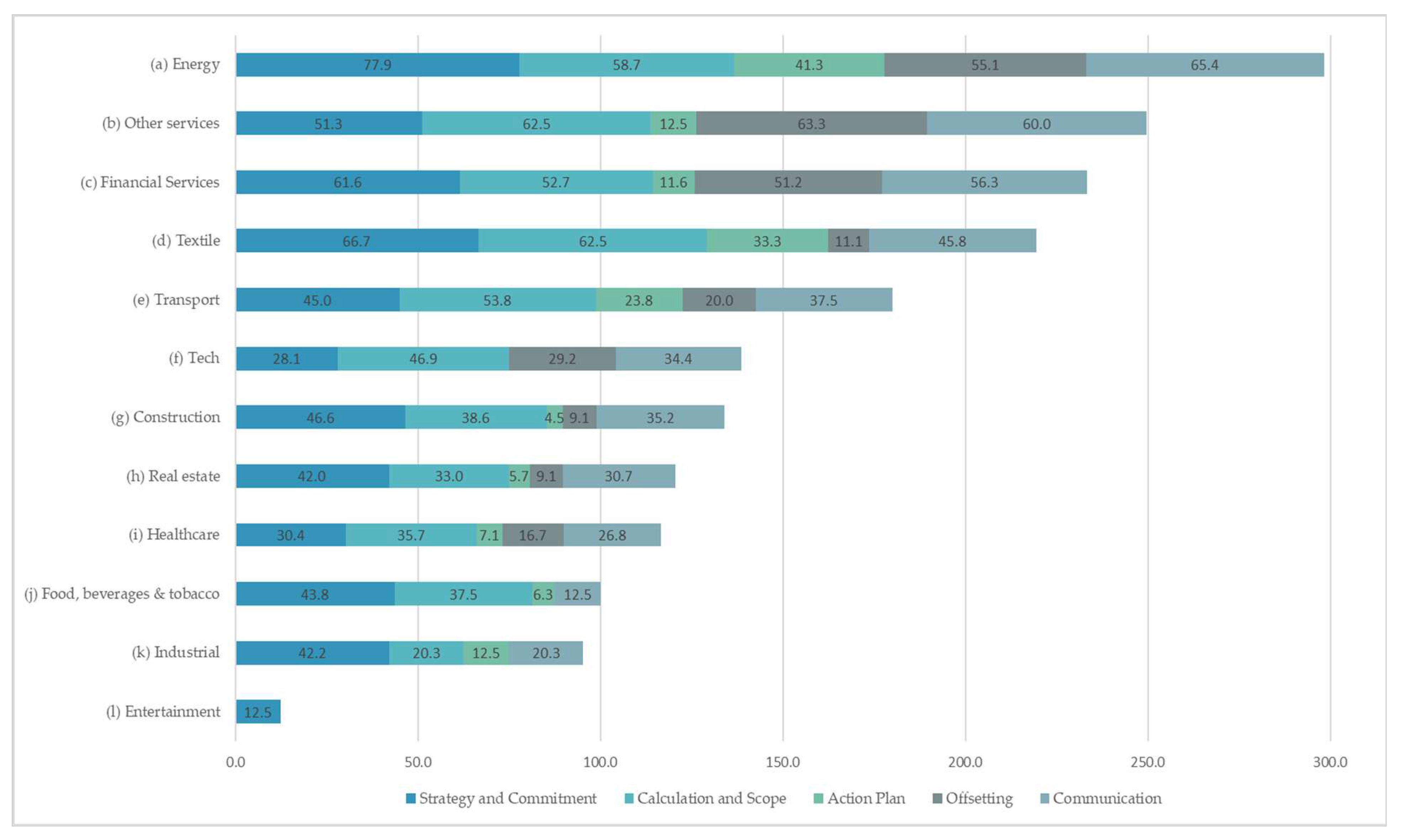

4.1. Sectoral Results

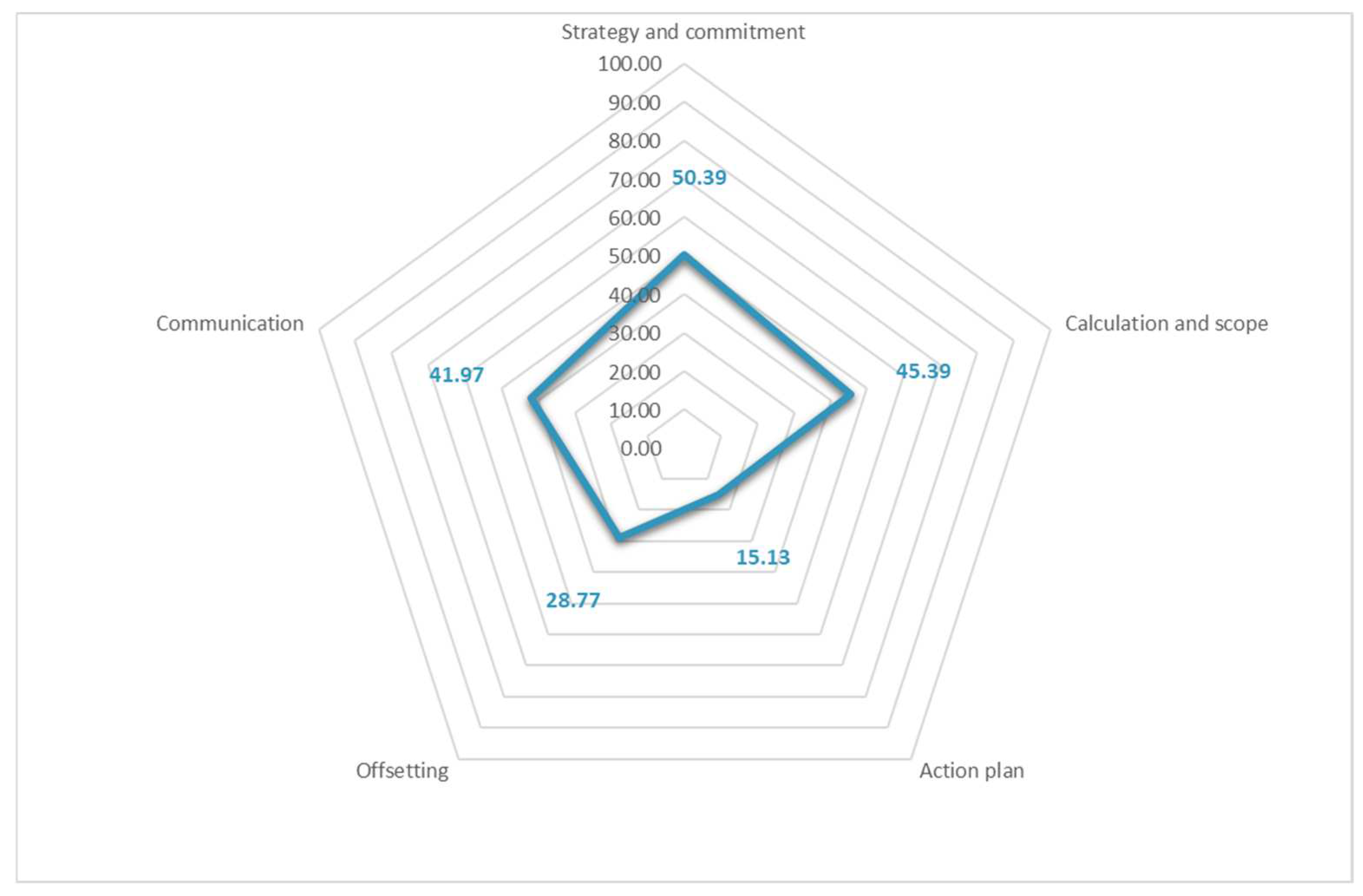

4.2. Global Results

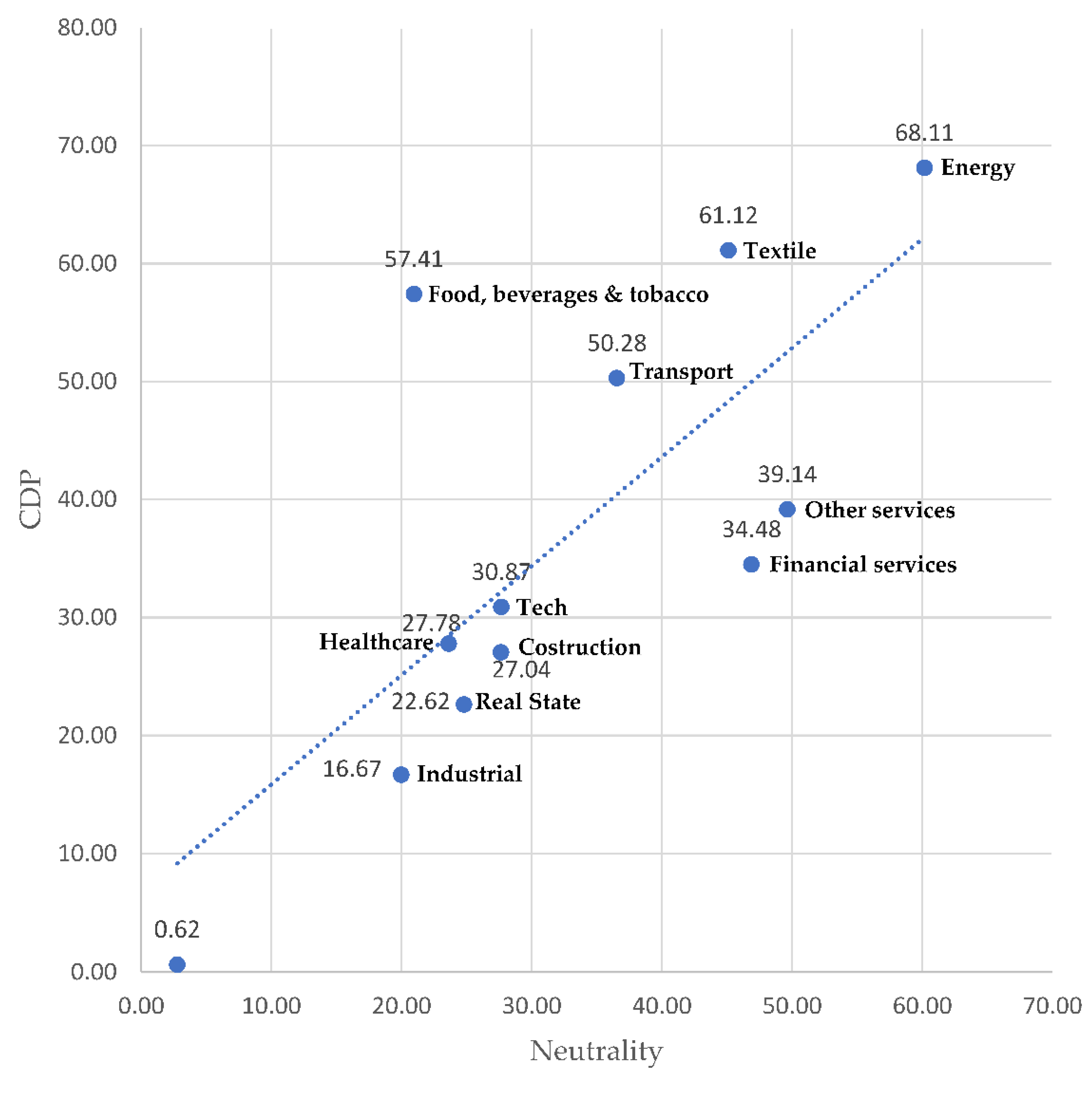

4.3. Correlation between Neutrality Claims and CDP Scores

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC Global warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change. IPCC Sr15 2018, 2, 17–20.

- Grainger, A.; Smith, G. The role of low carbon and high carbon materials in carbon neutrality science and carbon economics. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 49, 164–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M. Carbon neutrality: Toward a sustainable future. Innovations 2021, 2, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change). Paris Agreement (Spanish). In Proceedings of the Paris Climate Change Conference. Paris, France, 12 December 2015; p. 29.

- United Nations Environment Programme. Emissions Gap Report 2020; United Nations Environnmental Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2020; ISBN 9789280738124. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, K.; Rich, D.; Ross, K.; Fransen, T.; Elliott, C. Designing and Communicating Net-Zero Targets. Working Paper; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- CISL. Targeting Net Zero. A Strategic Framework for Business Action; The Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorn, A.; Lloyd, S.; Matthews, D. From the Paris Agreement to corporate climate commitments: Evaluation of seven methods for setting “science-based” emission targets. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Science Based Targets Foundations for Science-Based Net-Zero Target Setting in the Corporate Sector; CDP: Berlin, Germany, 2020.

- Wu, X.; Tian, Z.; Guo, J. A review of the theoretical research and practical progress of carbon neutrality. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2021, 3, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Climate Institute & Data-Driven EnviroLab. Navigating the Nuances of Net-Zero Targets; NewClimate Institute & Data-Driven EnviroLab: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.; Zhang, Y.; Mirza, N.; Umar, M.; Rizvi, S.K.A. The impact of carbon neutrality on the investment performance: Evidence from the equity mutual funds in BRICS. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanda, K.K.; Hartman, L.P. The Ethics of Carbon Neutrality: A Critical Examination of Voluntary Carbon Offset Providers. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 119–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogelj, J.; Geden, O.; Cowie, A.; Reisinger, A. Net-zero emissions targets are vague: Three ways to fix. Nature 2021, 591, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trexler, M.C.; Kosloff, L.H. Selling carbon neutrality. Environ. Forum 2006, 23, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Broadstock, D.; Ji, Q.; Managi, S.; Zhang, D. Pathways to carbon neutrality: Challenges and opportunities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.; Cullen, K.; Fay, B.; Hale, T.; Lang, J.; Smith, S. Taking Stock: A Global Assessment of Net Zero Targets. Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit and Oxford Net Zero; Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit and Oxford Net Zero: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Global Climate Action. Climate Action Pathway—Finance; Global Climate Action & Marrakech Partnership: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford. Mapping of Current Practices around Net Zero Targets; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Giesekam, J.; Norman, J.; Garvey, A.; Betts-davies, S. Science-Based Targets: On Target ? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Action 100+. Climate Action 100+ Net Zero Company Benchmark; Climate Action 100+: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- SBTi. SBTI Corporate Net-ZeroStandard 1.0; The Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi): Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- GSMA. In Carbon Trust the Enablement Effect. The impact of Mobile Communications Technologies on Carbon Emission Reductions; GSMA: London, UK, 2019.

- Umar, M.; Ji, X.; Mirza, N.; Naqvi, B. Carbon neutrality, bank lending, and credit risk: Evidence from the Eurozone. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System EN; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Volume COM. [Google Scholar]

- Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets. Phase 1—Final Report; Institute of International Finance: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rayer, Q.G. Why Ethical Investors Should Target Carbon-Neutrality. In Proceedings of the Pre-release of proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Energy and Environment Sensing (SEES 2018), Cambridge, UK, 18–19 June 2018; Fitzwilliam College, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

| University of Oxford: ‘Taking Stock: A Global Assessment of Net-Zero Targets Report Published’ | University of Cambridge: ‘Targeting Net-Zero: A Strategic Framework for Business Action’ | SBTi: ‘Foundations for Science-Based Net-Zero Target Setting in the Corporate Sector’ and Corporate Net-Zero Standard | Climate Action 100+: ‘Net-Zero Company Benchmark Framework’ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Timeframe (by 2050) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Target status | ✓ | ||||

| Interim goals | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Published plan/strategy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Annual reporting/transparency | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Use of offsets | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Criteria | Weight | Sub-criteria | Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy and commitment | 0.22 | Plausible with existing tools and resources | Is the neutrality claim feasible taking into account the tools, resources, and strategy deployed? |

| Intermediate deadlines | Are there intermediate deadlines such as 50% neutrality by 2030? | ||

| Responsibilities assigned | Has the company appropriately delegated responsibilities in terms of environmental sustainability and climate change within the organisation (who is responsible for what)? | ||

| Considering climate risks | Has the company considered climate risks within its risk management and sustainability strategy? | ||

| Calculation and scope | 0.20 | Scopes considered | Has the company calculated its carbon footprint? Which scopes? |

| GHGs included | What GHGs are considered when calculating the company’s carbon footprint? | ||

| Carbon removals | Does the company make use of CO2 removal projects (usually referring to the planting or conservation of forests and other carbon sinks) to absorb emissions from its value chain, as well as the use of Nature-based Solutions (NBS)? | ||

| Footprint certified | Does the company certify the calculation of its carbon footprint by third parties (agents external to the company)? | ||

| Action plan | 0.20 | Action plan budgeted | Does the company have a carbon neutrality action plan and an investment budget to achieve net-zero? |

| Cost-effectiveness analysis | Has the company performed a cost-effectiveness analysis? | ||

| Balance between reduction and offsetting | Does the company strike a balance between offsetting emissions as a transitional tool and reducing emissions towards net-zero? | ||

| Science based target | Has the company committed to science-based targets under the SBTi or in general, not necessarily to the SBTi net-zero standard? | ||

| Offsetting | 0.18 | Requirements for project types | Does the company have requirements on the types of projects with which it offsets its carbon footprint? |

| Requirements for project standards | Has the company established requirements on the standards regarding offset projects? | ||

| Cobenefit inclusion | Does the company include co-benefits as a requirement for the selection of offset projects? | ||

| Communication | 0.20 | Transparency over goals | Is the company transparent when communicating its neutrality objectives? |

| Transparency over calculation | How transparent is the company with respect to the published communication regarding the calculation of its carbon footprint? | ||

| Transparency over offsetting | How transparent is the company with respect to the information published on its emissions offsetting practices? | ||

| Neutrality certified | Does the company certify its carbon neutrality through third parties and under initiatives such as Publicly Avalailable Specification (PAS) 2060? |

| Sector | Number of Companies | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Energy | 13 | Energy production or management |

| Financial Services | 14 | Banks and insurance companies |

| Textile | 3 | Textile companies |

| Construction | 11 | Construction and infrastructure |

| Transport | 10 | Logistics, production of vehicles, and transport infrastructure |

| Technology | 4 | Technological and digital development |

| Real Estate | 11 | Real estate agencies and hotels |

| Healthcare | 7 | Pharmaceutical and cosmetics |

| Food, beverages and tobacco | 2 | Food processing and retail |

| Industry | 8 | Metallurgy, glass, and paper production |

| Entertainment | 2 | Amusement parks, gambling, and casinos |

| Other services | 10 | Communication, telecommunications, and security |

| Sectors | Average of Total Weighted Score |

|---|---|

| Energy | 60.18 |

| Other services | 49.64 |

| Financial services | 46.89 |

| Textile | 45.12 |

| Transport | 36.55 |

| Tech | 27.68 |

| Construction | 27.65 |

| Real estate | 24.82 |

| Healthcare | 23.63 |

| Food, beverages and tobacco | 20.97 |

| Industrial | 20 |

| Entertainment | 2.77 |

| Total general | 36.81 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Larrea, I.; Correa, J.M.; López, R.; Giménez, L.; Solaun, K. A Multicriteria Methodology to Evaluate Climate Neutrality Claims—A Case Study with Spanish Firms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074310

Larrea I, Correa JM, López R, Giménez L, Solaun K. A Multicriteria Methodology to Evaluate Climate Neutrality Claims—A Case Study with Spanish Firms. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):4310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074310

Chicago/Turabian StyleLarrea, Iker, Jose Manuel Correa, Rafaella López, Lidia Giménez, and Kepa Solaun. 2022. "A Multicriteria Methodology to Evaluate Climate Neutrality Claims—A Case Study with Spanish Firms" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 4310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074310

APA StyleLarrea, I., Correa, J. M., López, R., Giménez, L., & Solaun, K. (2022). A Multicriteria Methodology to Evaluate Climate Neutrality Claims—A Case Study with Spanish Firms. Sustainability, 14(7), 4310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074310