1. Introduction

Most of us love coastal areas and want to access them freely. Today, an estimated 40% of the global population live within 100 km of the coast [

1]. However, will they have access to enjoy the seashore or beaches? (In the context of this paper, we use the terms “seashore” and “beaches” interchangeably.) In many countries, the public’s expectation to have the right to access the beach is embedded in ancient tradition or law. Accessibility is today also part of the broad conception of integrated coastal zone management—ICZM [

2,

3] (

ICZM Protocol to the Barcelona Convention and the

Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council… Concerning the Implementation of Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Europe). However, heightened beach access rights inevitably entail more anthropogenic disturbances to the ecosystem. With the growing threats of sea level rise, tensions between beach access rights and urban sustainability are growing [

4]. In this paper, environmental sustainability will play in the background, to be addressed again when it appears in legislation or court decisions regarding beach access rights.

A daily and highly visible arena of conflict surrounding coastal areas is caused by their attributes as prime real estate locations [

5]. Attempts to extend public access rights will likely encounter opposition from private real estate interests and from government financial and political interests. As Thom [

6] argued, beach access is inherently a highly contested issue. Conflicts might occur between landowners on or near the beach and public groups arguing “the beaches are ours”; between the wealthy who can purchase apartments with a sea view and those whose view is blocked; and between socio-economic groups who can pay high beach access fees, and those who cannot afford to do so [

7]. The rising commodification of real property potentially exacerbates such conflicts. If one adds the special challenge of enabling beach access for people with disabilities, the potential for clashes among competing objectives becomes even higher. How should such clashes be resolved?

There are no globally consistent answers. This paper does not propose specific normative rules but, rather, presents the many different legal and regulatory approaches among a large set of countries. The readers are challenged to rethink their own countries’ coastal access rights now through the prism of what could be learned from other countries—whether positively or negatively. We also try to go beyond the usual legal frameworks and highlight relevant social-distributive issues that might arise. The paper concludes with some thoughts about emerging trends towards international convergence and how these might be enhanced.

2. Research Questions and Method

This paper looks at the ways and degrees to which the right to coastal access is addressed. The overall research question is: How, or to what extent, do the laws, regulations, and policies in a selected group of countries address the public right to access in coastal areas? There are two secondary questions: What are the major differences across the countries studied? And are there any trends visible over time?

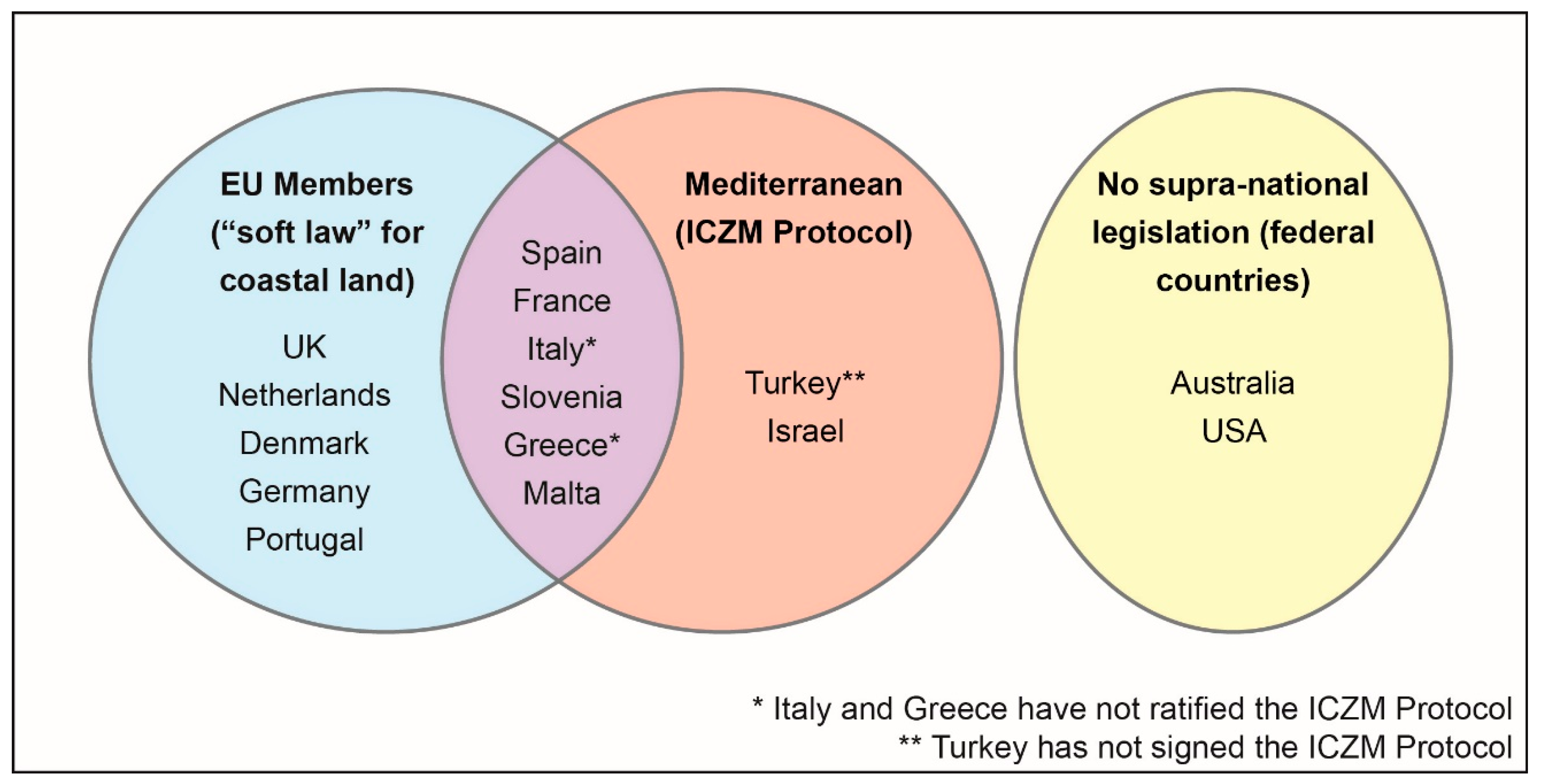

The questions were posed in relation to national-level laws and policies in 15 selected countries (

Figure 1). Based on a set of shared parameters and evaluation criteria, we analyse the similarities and differences regarding coastal access rights. The analysis is applied to the legislation and “soft law” documents in each of the selected jurisdictions, and also relies on relevant academic publications. The information about each jurisdiction is based on an analytical report written by a leading academic expert (one or two per country) whom we invited to participate in an academic book

Regulating Coastal Zones: International Perspectives on Land Management Instruments. We shall cite their individual work frequently in this paper. Our collaborators in the book project are: Anker (Denmark), Balla & Giannakourou (Greece), Carmon & Alterman (Israel), Correia & Calor (Portugal), Falco & Barbanente (Italy), Gurran (Australia), Jong & van Sandick (Netherlands), Marot (Slovenia), McElduff & Ritchie (UK), Prieur (France), Schachtner (Germany), Tarlock (USA), Ünsal (Turkey), Vallvé, Molina Alegre & Pellach (Spain), Xerri (Malta). Their contributions are cited throughout this paper. The country chapters were written according to a rigorously shared framework addressing a set of parameters drawn from the principles of ICZM [

8]. Accessibility was only one among ten parameters discussed in the book.

Due to the quintessential role of beach access as an expression of the broader values underlying coastal zone management, we devote this entire paper to the topic. The paper goes beyond the information provided in the book in three ways: First, for this paper we conducted a broad survey of current international academic knowledge specifically about beach access. Second, we were able to expand and deepen the theoretical framework dedicated to analysing accessibility rights. Third, the scope of the comparative analysis of access rights presented here goes well beyond the limited space we were able to devote to it in the book ([

9], pp. 408–415). For this paper, we undertook further “mining” of the factual and analytical information provided by each country-chapter authors and are thus able to present comparative analysis and evaluation well beyond what is provided in the book.

In addition to looking at each country’s individual laws and policies, we also look upwards, at international law about ICZM. This is a unique area of international legislation and supra-national “soft law” which exists only for a limited number of countries. We selected the research countries so that 13 of our 15 countries do come under international or supranational legislation or “soft law” (government policy documents).

Figure 1 displays the selected countries divided into groups according to the relevance of supra-national legislation of policy.

In selecting the set of countries (or states) for the comparative analysis, we made sure there would be a sufficient common denominator to enable cross-country learning to some degree. At the same time, we wanted to represent enough diversity to reflect the legal complexity. The common denominator is that all selected countries have advanced economies and a reasonably working governance system (and most are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development—OECD. The rules of membership in the OECD are that the candidate country has a well-developed economy and a reasonably working (democratic) government. One country, Malta, is not yet an OECD member). Of the 36 OECD member countries in 2020, our set in fact represents a hefty 40%. Our study does not include developing countries.

The discussion begins with a conceptual classification of categories of accessibility. These will serve as the framework for analysing beach access rights in law and practice across the selected countries. Next, we review the academic literature, in order to place our contribution within the current state of knowledge. The paper then introduces the relevant international law about ICZM and coastal access rights. The factual (legal regulatory) information in the paper draws on the findings from the 15-country reports analysis, where we point out similarities and difference and attempt to gauge emerging trends. Throughout, we try to point out potential distributive justice issues. These are usually not spelled out in ICZM guidelines nor in national coastal laws. We end by pointing out the major challenges that still await further legal and policy research, and action.

3. Conceptual Framework: Categories of Public Accessibility and Their Inherent Conflicts

Here we present our conceptual framework, which will serve as the backbone for the comparative analysis of the selected countries.

The most basic notion of the public’s right to coastal access is dictated by geography: a defined strip along the coast where public access is permitted. A related notion is whether and how that coastal strip can be physically reached from the hinterland. To these dual categories we propose to add two more. The four categories are:

Horizontal (lateral) accessibility—the public right to swim, walk, hike bike, play, relax, etc., along the seashore.

Vertical (perpendicular) accessibility—the public right to reach the seashore from the urban or nonurban hinterland.

Visual accessibility—ability of the public to view the coast from within the city.

Accessibility for people with physical disabilities.

Importantly, the underlying definitions of the “public” differs across these categories. The first category is usually defined according to an objective geographic area (it may fluctuate with the tidal movements). In demarcating the zone in which horizontal access is a right, the “public” of users is usually general and anonymous. In the second category, vertical access, there is often some discretion about where to locate the publicly accessible routes, and, thus, location-specific and community-specific publics may have better access than others. In the case of visual access, the public served is on the move and enjoyment of the coast depends (literally) on one’s point of view. The view from particular neighbourhoods (or office buildings) could be given preference. Thus, social-distributive considerations could be relevant both to vertical and visual accessibility. Finally, the public in the fourth category refers to persons or communities with specific needs, and the right of access would likely be available only in special locations rather than as a general legal rule. The public targeted here—persons with physical disabilities—is usually a small minority, often disadvantaged in political influence and socio-economic terms.

Each of these categories of accessibility is likely to encounter differing configurations of conflicts: horizontal access rights on their own are ostensibly blind to social justice considerations because they tend to apply to a predetermined geographic zone and to the generic public. At the same time, horizonal access rights might clash head-on with real-property rights and economic interests. As we move down the list, social justice concerns play a more apparent role because determining the locations that enable the right of access involves greater discretion about location and extent. Site-specific decisions taken by legislators, planning bodies, or public finance bodies are not blind to population characteristics and, thus, distributive justice questions lurk behind.

4. Contribution to Current Knowledge

This paper (and the book on which it is partially based) seeks to fill a major gap in current knowledge. We hope to contribute at three levels: first, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic cross-national comparison of a large set of countries in terms of their legal and regulatory expression of beach access rights. Second, the paper encompasses all categories of beach access rights within a single conceptual framework. Third, this is the first paper to attempt to address the impact of international law and policy about coastal regulation on the national laws and policies of the signatory countries (the majority among the 15).

In scanning current literature (in the English language), we identified only one legal paper where beach access rights are compared cross-nationally: Cartlidge’s [

10] excellent analysis compares Australia and the USA, and also differentiates among some state jurisdictions in these federal countries. Country-specific research is more prevalent (not only in English). Much of it is cited by the authors of each country report in our book, and we will not repeat it here. Most previous literature covers only the horizontal or vertical categories of access. This is not surprising, because these categories also attract the most litigation, reflecting their direct interaction with property rights.

As we move up the categories of accessibility rights, academic literature on the legal and regulatory issues becomes more sparse. The third category—visual accessibility—is addressed in architectural and urban design literature about waterfront development, but we have not found any relevant studies about its legal and regulatory aspects. The fourth category of coastal accessibility—access for the physically disabled—draws the attention of social, public health, and tourism studies, but very little scholarship related to planning or property rights. We shall bring forth the relevant international literature as we discuss each of the categories of accessibility.

5. International Legal Norms

Public access to beaches holds a privileged status among other topics of land-related law. In many jurisdictions around the world, the right of public access is anchored in age-old tenets—“public domain” and “the “public trust doctrine”. Most dramatically—public access to coastal zones, as part of broader ICZM, has been uniquely “upgraded” to international law. We discuss these notions in greater detail.

5.1. The Public Trust Doctrine

In many jurisdictions, the legal history of public rights in coastal areas is tied to the “public trust doctrine”, which relates (or some argue, should relate) to some types of natural resources [

11]. Historically, this doctrine was codified by Emperor Justinian in the 6th Century Byzantine Empire based on Roman common law. The often-cited principle states:

“By the law of nature, these things are common to mankind—the air, running water, the sea, and consequently the shores of the sea”

(cited in [

2], p. 3; see also [

11], p. 711).

This doctrine is not exclusive to the Roman Law tradition and has been independently developed in some other parts of the world—with varying legal interpretations across jurisdictions and over time [

12]. In some countries, the public trust doctrine is manifested through publicly owned land ownership along the seashore. As we shall see, this is dominant among the set of countries analysed here. In some other countries, such as the UK, Australia, and five US coastal states, where private land ownership extends into the sea, the public trust doctrine is sometimes invoked to interpret the weight to be given to beach access rights. The interpretation of the public trust doctrine tends to be in legal flux, and thus has drawn an extensive literature; see, for example, [

13,

14,

15,

16].

5.2. Public Beach Access in International Law (Mediterranean) and EU Recommendation

To what extent does international law require, or incentivize, nations to adopt rules of beach access rights? As shown in

Figure 1, in our set of countries, 13 of the 15 come under the canopy of at least one of two relevant international documents. Two countries—the USA and Australia—are not legally affected by any supra-national rules for ICZM.

In 2008, an unprecedented step was taken when the notion of integrated coastal zone management was elevated to the realm of international law. The legislation, the Barcelona Convention Protocol on Integrated Coastal Zone Management for the Mediterranean (henceforth the Mediterranean ICZM Protocol [

17]), applies to all countries along the Mediterranean Basin [

18]. It was adopted as a unique multinational effort [

5,

19]. The Protocol was signed by 20 countries, plus the EU itself. It is relevant to all Mediterranean member states in our sample. Seven of our eight Mediterranean countries have signed the ICZM Protocol (Turkey has not but is eligible to do so). Five of these have already ratified the Protocol, thus rendering it part of their domestic law; Italy and Greece have not.

A few years earlier, in 2002, the European Parliament adopted an important “soft law” document—the Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council… Concerning the Implementation of Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Europe [

20], applicable to all EU member states (henceforth EU ICZM Recommendation). In our study, there are five countries outside the EU: the USA, Australia, Turkey, Malta, and Israel. The two sets of rules (Mediterranean ICZM Protocol and EU ICZM Recommendation) are legally independent, and they both apply to several of our sample countries which are both Mediterranean countries and EU member states (

Figure 1). Six of the Mediterranean countries are also members of the EU and thus come under both umbrellas—the ICZM Protocol and the EU ICZM Recommendation. One country—Israel—is bound only by the ICZM Protocol.

These two international law/soft law documents are unique because they apply directly to land ownership and regulation. Nations are usually reluctant to agree to international law that would intervene directly in their land issues. This sensitivity probably reflects the very local attributes of property law, its intensive socio-political repercussions, and the high economic value of real-estate. We recount elsewhere the story of how the European Parliament backed off from its initial intention to include both the sea and coastal land in a binding Directive (as any ICZM textbook would recommend). Instead, the EU had to be satisfied with a binding directive only for the sea (Directive 2014/89/EU of the European parliament and of the council of 23 July 2014 establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning [

21]), and a soft-law Recommendation for coastal land ([

22], pp. 5–7).

Let’s look first at how the right of access to the coastal zone is address by the Mediterranean ICZM Protocol. The quote below is drawn from the “criteria for sustainable use of the coastal zone” [

17]:

“… providing for freedom of access by the public to the sea and along the shore”

(Article 3(d)).

The wording pertains to two types of access; to the sea (which we called vertical or perpendicular accessibility) and along the shore (horizontal accessibility). The two other types of accessibility are not addressed. The Protocol is binding for the signatory countries at the international law level and for those countries that have also ratified it—also in domestic law (See

Figure 1). However, international law on such topics is difficult to enforce.

The second international document is the 2002 EU ICZM Recommendation, which addresses the public right to access the coast thus:

“… adequate accessible land for the public, both for recreational purposes and aesthetic reasons”

Neither legislation stipulates any further rules or criteria of what constitutes “freedom of access” or “adequate accessible land”. However, these documents were clearly intended to stimulate public awareness and discussion of how these norms should be anchored in domestic (national) legislation, statutory plans, or other policy statements.

Beyond our praise for the elevated standing of beach access rights in international law, the reports about the relevant countries indicate that, in reality, neither of these documents have had much direct legal influence. This means that there is little evidence that they have been cited and applied in national (domestic) legislation or court decisions. This holds even for those Mediterranean countries that come under both international documents and have ratified the Protocol. Furthermore, even if the relevant clauses were to be invoked before the courts, the vague wording of both statements about access would be difficult to apply in contested cases.

The focus in our comparative analysis, therefore, remains at the level of each country’s internal laws and policies. The analysis will follow the conceptual framework presented above. However, in order to understand some of the legal regulatory concepts related to coastal accessibility in each selected country, we must take a short detour to discuss an underlying legal factor: is there a legally grounded “coastal public domain”?

6. Is There a Coastal Public Domain in the Research Countries?

Before presenting the comparative analysis according to each of the four categories of accessibility rights, it is important to look at whether coastal access rights can be facilitated by a pre-existing “coastal public domain”. This term often refers to a legally defined, publicly owned strip (or under sovereign trust) along the coast, landwards from the territorial waters line.

Public land ownership or management is viewed by many, even today, as potentially more effective in protecting the coast from overdevelopment than land-use regulations alone. In many countries, there is some degree of public land ownership along the coast, often based on generations-old law. Yet, this is not a global rule. In some other countries or sub-national jurisdictions, even among EU members, there is no established public domain landward from the shoreline, and private land ownership may be permitted all the way into the sea. An example is Finland—an EU and OECD member country not included in this research—private land ownership is permitted even seaward of mean low water ([

23], p. 165). The widespread presence of coastal public domains distinguishes coastal zones from some other land uses with distinct public value, such as forests.

It so happens that most of the nations in our set do have some form of a legally defined coastal public domain that the public can freely access (excepting specific areas such as ports or sites with unique environmental value). However, location and scale differ significantly across our jurisdictions. Where the public domain is submerged all year-round, it may be useful for boating, fishing, etc., but not for the many beach activities on dry or part-dry beaches.

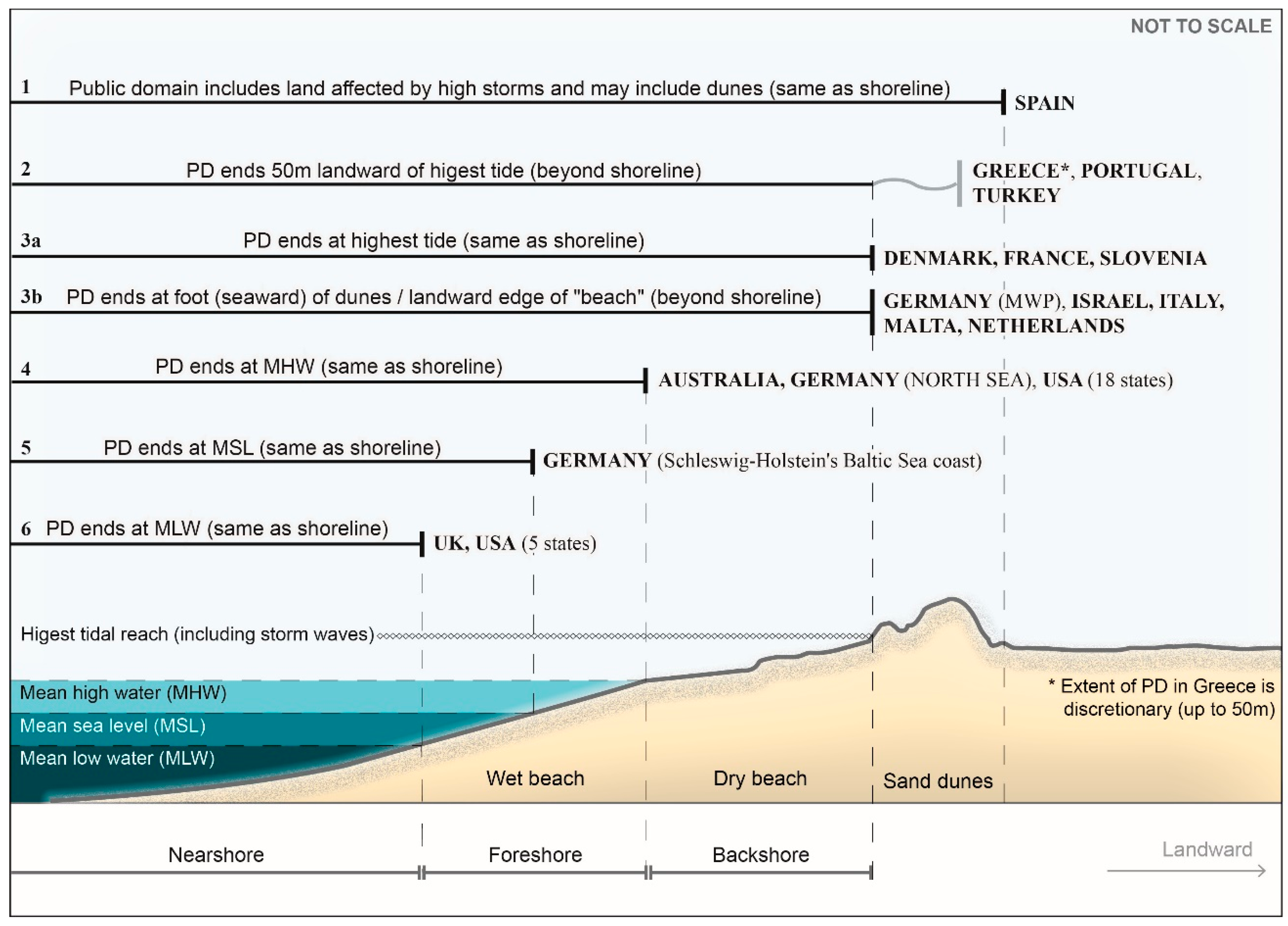

Figure 2 visually depicts our comparative analysis of the landward reach of coastal public domain in the research jurisdictions (In the seaward direction, coastal public domains usually extend to the limit of the jurisdiction’s territorial waters, but this is not relevant to the current research). We place the jurisdictions along a schematic scale of coastal topography, to indicate how far their public coastal land ownership extends landwards. In the discussion of each category of accessibly, we shall see that some jurisdictions have gradually gone beyond what their current public domain allows but have had to invent creative legal arrangements to enhance their right to coastal access.

The jurisdictions on the lower rungs of the scale (rung 6) have been historically unlucky—they inherited legal rules whereby the public domain is almost always under water. Thus, private ownership may extend well into the water, and if no other government rules are imposed, the under-water beach too would be private. These jurisdictions are the UK [

24] and five among the US coastal states [

25].

Figure 3 vividly portrays the attitude of an anonymous beach-front property owner who warns of criminal action against anyone who accesses the beach. The emphasis conveyed is that walking along the beach is not allowed even in shallow water, when the tides cover beach (which probably means most seasons).

In several other jurisdictions—rungs 5 and 4—the public domain is in the “wet beach” zone, which is covered and uncovered by tidal waters under normal conditions (three of the four German coastal states [

26]; Australia [

27]; and all other US coastal states [

25]). In the remaining jurisdictions—the “lucky” ones for public access—the public coastal domain extends landwards, to the “dry beach” (which is affected only by the highest tides), up to the sand dunes or even beyond. These jurisdictions are Portugal [

28]; Spain [

29] Netherlands [

30]; Denmark [

31], Germany’s state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania [

26], France [

32]; Italy [

33]; Malta [

34]; Greece [

35]; Slovenia [

36]; Turkey [

37]; and Israel [

38]. If we were to announce an international competition, the “winner” would be Spain: Its coastal public domain extends the furthest inland (despite some recent minor legislative changes; [

29]).

Because we are analysing a relatively large set of national and subnational jurisdictions, we are able to observe whether there are emerging trends. For example, are there jurisdictions that attempt to extend their public domain beyond what was achieved many decades or centuries ago, when population densities and real estate prices were much lower? As may be expected, this is rare. However, we can highlight two countries that have expanded their previous public domain successfully in recent decades. These are Spain and Slovenia. In 1988, Spain extended its previously narrow public domain far landward, but this achievement came at the price of legal turbulence and intensive social conflicts that still linger on [

29]. Another country, Slovenia, instituted its public domain relatively recently—after the country became an independent democracy [

36]. Decision makers at the time may have known how to seize the crisis opportunity and add public domain to the drastic changes that were instituted in law and governance.

Countries where the public domain is submerged most of the year may try to harness other available legal instruments to provide horizontal and other access rights to dry beaches. There will inevitably be significant differences across countries. We, therefore, turn to analysis of the 15 countries in terms of each of the four categories of accessibility.

7. Comparative Analysis Applying the Four Categories of Coastal Access Rights

Table 1 presents a comparative summary of the four categories of accessibility. This will serve as the anchor for the discussion to follow, where each category of access rights is addressed in depth.

Table 1.

The categories of accessibility: comparative findings.

Table 1.

The categories of accessibility: comparative findings.

| Degree of Specificity of National or Subnational Legislation | The Categories of Accessibility |

|---|

| Horizontal | Vertical | Visual from Hinterland | Access for Persons with Disabilities |

|---|

| No rules | Australia (but local level is empowered)

Malta (national plan with rules was cancelled)

UK (but 2009 legislation for England incentivizes a contiguous path) | Australia (but local level is empowered)

Netherlands

Germany—Some states have “the right to roam” in open land

Malta

Slovenia

UK

USA—most states | Australia

Denmark

France

Germany

Greece

Italy—national level

Malta

Portugal

Slovenia

Turkey

UK

USA | Australia

Denmark

France

Germany

Greece

Italy—national level

Malta

Netherlands

Portugal

Slovenia

Spain

Turkey

UK

USA |

| General normative statement | Denmark

Germany (some states also have “the right to roam” in open land)

Greece

Israel

Netherlands

Portugal

Slovenia

Turkey

USA—varies by state; see Figure 4 | Denmark—plus the general “right to roam”

Israel (in national statutory plan; following court decisions)

Italy (most extensive is Puglia Region) [32]

Portugal

Turkey

USA—California, New Jersey | Italy—Puglia region

Netherlands

| Israel

Italy—Puglia Region |

Numerical standards or other

concrete criteria | France (3-metre-wide easement along the outer edge of the MPD)

Italy (access along beach within 5 m of shoreline)

Spain (6-metre easement at outer edge of MTPD) | Greece (10 m-wide coastal access roads); ineffective

Spain (Roads every 500 m, pedestrian paths every 200 m)

France–paths or roads recommended every 500 m | Spain—added architecture-based rule

Israel—new national statutory coastal plan requires mandates “visual impact statement” | - |

7.1. Horizontal Accessibility

A general national or subnational right to horizontal access along the coast is, as already noted, the basic and probably the oldest tenet of coastal zone accessibility. As we saw, both international legal and soft-law documents refer explicitly to this right. We therefore placed horizontal access first in

Table 1, which shows that, in most of our research countries, national-level laws and regulations do address such rights, but with important differences.

Because horizontal access is closely connected with public land ownership, it is usually expressed in the form of some minimal strip of contiguous publicly owned land. Where the public domain is under water or is very narrow, provision of horizontal access may require other legal and policy measures. Where such measures were not implemented when development pressures and property values were low, a “retrofit” today would be a major legal and financial challenge due to pre-existing private property rights or expectations of development. Nevertheless, as we shall see, even in some countries, we witness attempts to extend the geographic bounds of horizonal accessibility by harnessing alternative legal tools.

We first discuss those jurisdictions that do have at least some dry beach public domain, and then we look at those without a dry beach public domain. In each case, we will refer to the manner in which horizontal access rights are addressed in national legislation or regulation, as summarised in

Table 1.

7.1.1. Jurisdictions with a Dry-Beach Public Domain

Several among the research countries with a dry beach public domain have elected to go beyond a general normative statement about access rights to provide geographically specific numeric standards (for better or for worse); in Italy, the law states that horizontal access should be provided within the 5 m closest to the shoreline (defined according to high tide; [

33]). As Italy’s public domain extends beyond the shoreline to the edge of the dry beach, this requirement both adds an additional “safeguard” for access along the beach and protects horizontal access in areas where there is no beach (e.g., cliffy shores) or where the beach is very narrow. France and Spain adopt a different approach—they provide additional public easements at the outer edge of their landward public domain. The French rule is 3 m and the Spanish 6 m. Because Spain’s public domain is the most extensive, this means that, with this supplement, Spain grants the most generous horizontal access rights [

29].

The public domain in Israel also extends landwards to the dry beach, but there are legal challenges in keeping commercial concessions away. The beaches in Israel are becoming very crowded due to the country’s extremely high population growth rate and high population density. Over time, local governments granted various concession rights to commercial operators. Protection of the beaches from development, including access rights, has become a major rallying point for environmental NGOs. In 2004, the Coastal Protection Act was adopted as the result of concerted action by a coalition of NGOs. The new law, replacing prior reliance on national planning regulations, gave national and local government stronger implementation and enforcement instruments. They have been successful in pushing permitted commercial concessions to the back of the beach, allowing for continuous open horizontal access [

38].

The story of Malta, as recounted by Xerri [

34], is unique because the country only introduced a formal coastal public domain as recently as 2016. Prior claims of historic private ownership mean that much of the land within the public zone is privately owned—making Malta more comparable with jurisdictions without a dry beach public domain. The 1992 National Structure Plan had included a requirement that, in approving new development, the planning bodies would assure beach access “around the shoreline immediately adjacent to the sea or at the top of cliffs”. However, this plan was later repealed by a government decision due to criticism by landowners and developers. The strip of land that should have been dedicated to the public for horizontal access has apparently been largely overtaken by private development, often illegally [

34]. Malta’s legislators and government bodies have tried to find alternative modes, primarily through planning and building controls. However, this has turned out to be especially difficult in Malta due to its highly conservative conception of property rights as expressed in court rulings.

7.1.2. Jurisdictions without a Dry-Beach Public Domain

There are several jurisdictions without a public domain along the dry beach. We focus here on Australia and the UK and address the special case of the USA under a separate subheading.

In Australia and the UK, horizontal access rights are not explicitly anchored in any national (or state) legislation or regulation. Nevertheless, the importance of horizonal access rights is recognised and each country has instituted some policies to overcome the absence of a historic public domain.

Although, in Australia, accessibility of any type is left to the will of the subnational levels, in practice, horizontal access is broadly (but inconsistently) enabled by the states and local governments [

27]. In the UK, a 2009 law adopted in England (but not Northern Ireland) has the highly ambitious objective of creating the English Coastal Route by incentivising (and helping to finance) co-operation with leading NGOs and local governments. In the meantime, the situation on the ground still varies greatly across local jurisdictions [

24,

41].

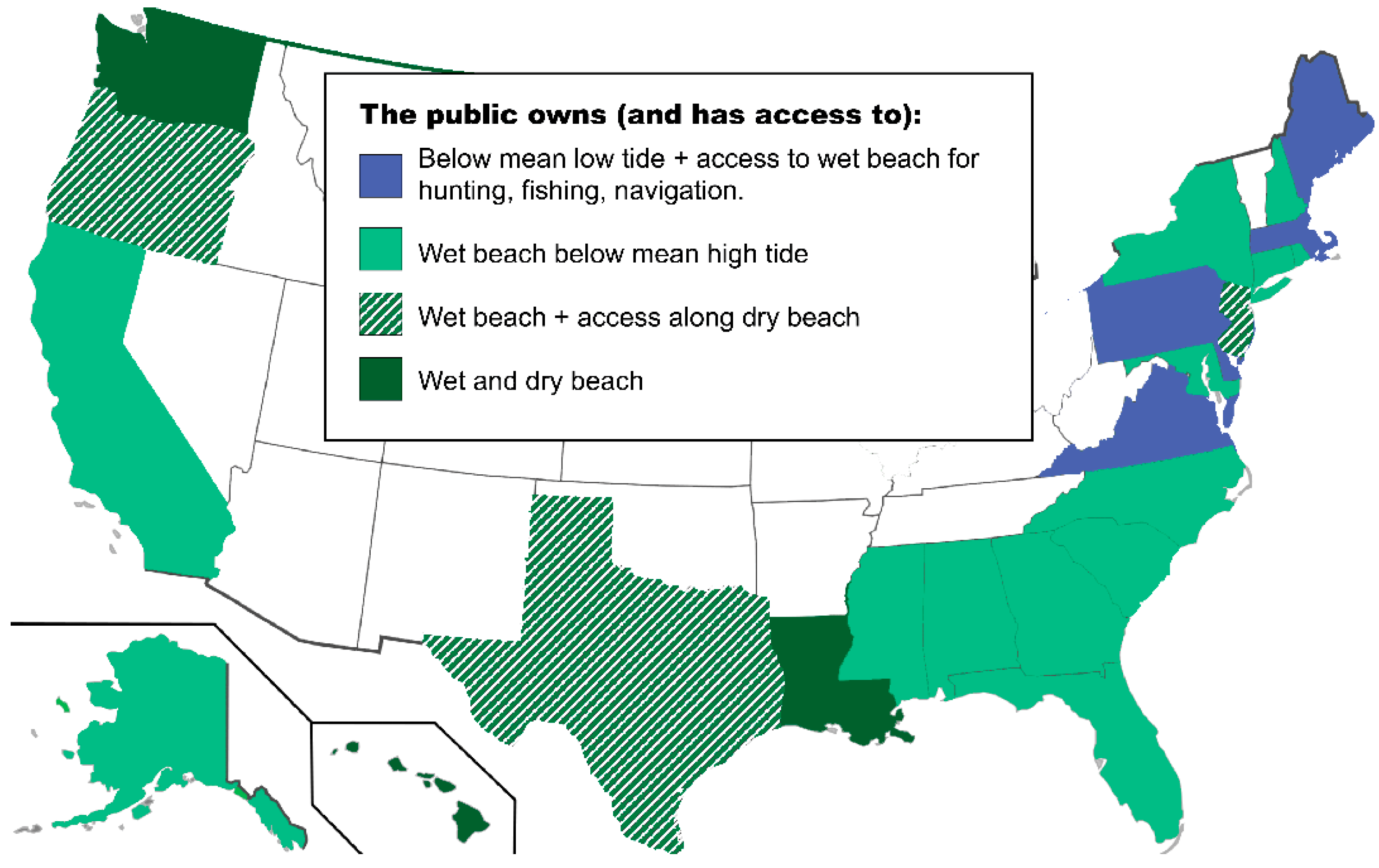

7.1.3. The “Regulatory Takings” Doctrine and Its Impacts in the USA

The USA provides an especially legally “unfriendly” context for the provision of both horizontal and vertical access. Recall from

Figure 2 that, in the USA, the public domain often does not extend over parts of the beach that are dry for much of the year. Public access rights are usually provided only along the submerged coastal strip (see

Figure 4 and [

25]). Thus, if members of the public can access the beach from some public venue, then they may be allowed to boat or swim in the water, including over privately owned land, but they will not be permitted to walk even within the water-covered part of the land. This is the situation also in the UK and Australia. However, as we have seen, these jurisdictions are incrementally providing what may be a more extensive proportion of coastal coverage of horizontal access rights than in the USA.

Where there is no general dry-beach public domain, governments may still be able to harness alternative legal or financial instruments to create a partial substitute for the public domain. Government authorities could purchase private land or undertake land expropriation (called eminent domain in the USA). Both would involve public expenditures and might instigate socio-political conflicts. Less drastic instruments could include voluntary donation of land by private or quasi-public owners; a precondition placed by planning authorities on development permission that the owner grant permission for public access of some form; a “deal” with the owner to provide public access in exchange for development rights elsewhere (“transfer of development rights”); or similar tools. However, the differences across countries in the capacity to apply such instruments depends, to some extent, on underlying legal differences in the conceptions of property rights. Here, the USA differs from most of the countries surveyed in this work.

In the USA, there is a persisting constitutional doctrine called “regulatory takings” [

42]. Based on this doctrine, a landowner could, in principle, argue before the courts that a regulatory interference in property rights (in fact meaning a property’s economic value) should be ruled as unconstitutional. Comparative research on regulatory takings [

43] has shown that, in this respect, the US is an “outlier” among the 13 countries studied. In the present discussion, the direct comparison regarding coastal access is the UK, Germany, and Australia. There, the regulatory takings concept is either non-existent or applies under limited conditions outlined in statutory law. Furthermore, in the USA, regulatory takings law is almost entirely the product of jurisprudence, with an unprecedently large and growing body of decisions [

44]. Thus, at any given point in time, government bodies often face legal uncertainty when they attempt to apply regulatory tools, such as zoning or development conditions to gain coastal access for the public—whether horizontal or vertical; see, for example, [

16,

45,

46]. It is, thus, not surprising that, in the present comparative study, the US falls in a category of its own, with little legal room for manoeuvre to achieve major legal transformations, even in the most basic category of beach access rights—horizontal access.

Despite these legal constraints, the establishment and operation of the California Coastal Commission shows that a concerted initiative supported by civil society can incrementally enhance beach access rights [

47]. The California Coastal Act states that “development shall not interfere with the public’s right of access to the sea”. Even though the Act does grant property owners the right to apply for a special permit to terminate a previously existing public access right, the California Coastal Commission does not grant such permits easily [

25]. The provisions of the Act cannot insulate it from challenges under the regulatory takings doctrine. A famous example is the 1987 US Supreme Court decision,

Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, 483 U.S. 825 (1987). It demonstrates the complexity of the legal challenges concerning all of our accessibility categories. The Court ruled that a condition imposed by the California Coastal Commission on owners who requested to replace an existing house with a larger one to require dedication of a horizontal strip. To just justify using a regulatory tool rather than expropriating the strip of land along the shoreline (and paying compensation), the Commission argued that the proposed structure would “wall off the view” of the coast from the road above, and the compulsory dedication of the strip of land would mitigate that. The Court rejected this rationale and ruled an “illegal taking” of private property. This decision has generated extensive academic discussion about the relationship between land use regulation and property rights in general [

48]. Nevertheless, several decades of legal experimentation and case-by-case achievements have placed California as a leader among US states in its quest to enhance public access rights along its coasts.

7.2. Summarizing Horizontal Accessibility

To sum up the horizontal access category: The countries in our set, among them many EU members, still differ greatly in the horizontal access rights they provide to the public. We did point out some instances of a positive momentum to enhance these rights in contexts where they are very limited, but such efforts do not alter the general picture. There are still major disparities in the interpretation and protection of horizontal access rights—the most basic type of coastal access rights. Citizens or visitors in our set of 15 countries will have very different experiences when they wish to access the beach, even for the purpose of simply taking a walk along the seashore.

8. Vertical (Perpendicular) Accessibility

In order to be able to walk along the coast, one needs to reach it from the hinterland—whether urban or nonurban. Unlike horizontal access, vertical accessibility is less geographically determined. There are often no historically preassigned vertical public rights of way. There is no shared norm about what a reasonable expression of vertical access would be and, unlike horizontal access, no internationally prevalent legacy of government responsibility.

8.1. Dilemmas Surrounding Vertical Access Rights

Many concrete questions arise regarding vertical access rights. Access from where to where? Who should be obliged to establish, finance, or maintain vertical routes? Should all access routes be located on public land, or should there be a right to pass through privately owned properties? What distinctions should be made between rural and urban areas? Should there be a norm of maximal distance between vertical access routes? In their quest to secure vertical access from within the city or region, government (or civil society) bodies are likely to encounter many conflicts between real estate considerations and beach-users’ interests. These might be even more diverse and complex than maintaining horizontal access.

To these dilemmas, one should add issues of social-distributive justice. Control of vertical access could be used as a socially exclusionary mechanism, as argued and empirically supported by Ernst [

7], Kim & Nicholls [

49], and Kim et al. [

50]. For example, high parking fees, absence of public transportation, delineation of routes that serve some communities more than others, and entry-right preference for local residents over outsiders (or the reverse)—all of these could challenge social-distributive justice in vertical coastal access. Since beach maintenance is also a public finance issue, the issue is who should bear the burden: local taxpayers? Regional or national taxpayers? Imposition of access fees (or parking fees) could help to regulate the overload, but such fees can also have a socially selective effect (see [

51]).

8.2. The Social Obligation of Property and “the Right to Roam”

Vertical access can be pre-planned (or retrofitted) through government action on public land. However, such routes are not always feasible and are necessarily inflexible. What if vertical access was permitted over privately owned land, where it does not interfere severely with privacy or with production? The issue of vertical access over privately owned land highlights some of the ideological differences between conceptions of private property rights.

In most jurisdictions in our sample, the law on real-property rights broadly follows the more traditional perspective, whereby passing through property without the owner’s permission is trespassing and is punishable. There are, however, several jurisdictions in our set where the ideology of property rights leans closer to the conception of “the social function of property” or “the social obligation of property” [

52,

53,

54]. In those countries, vertical accessibility to the coast is part of an over-riding right that members of the general public have the right to hike across and enjoy privately owned open land, under certain limitations. This legal approach is popularly known as “the right to roam”, and usually includes the beaches as open land.

Among our sample jurisdictions are several where there is a right to roam (but with detailed legal differences). These are Denmark [

31], three of the four coastal German states [

26] (the German state of Schleswig-Holstein recognizes the right to roam along the beach only, not to access private land vertically), Scotland, and, to a more modest degree, also England [

24]. In these jurisdictions, the issue of vertical accessibility to the coast is less acute. For example, in Denmark, as explained in detail by Anker [

31], the right to roam is deeply embedded in law and public expectations. One of the expressions of this right concerning coastal access is that existing footpaths leading to beaches across private uncultivated land may not be removed without special permission [

31].

8.3. Vertical Access Rights in National (or State) Legislation

Apart from the jurisdictions where the law recognises the right to roam, the others might face many property rights challenges in achieving vertical accessibility. Provision of public access paths could entail issues of land expropriation (“eminent domain” in the USA). Imposition of an obligation on private property is even more challenging.

We were, thus, happily surprised that most of our set of countries do address this topic within their national-level coastal legislation or regulations (see

Table 1). Denmark is notable in that its legislation goes beyond the general right to roam to embed vertical access rights in national legislation: vertical accessibility should be ensured and, if possible improved whenever new development is proposed within 3 km of the shoreline, as explained by Anker [

31]. This is an exceptionally generous rule.

Here are some more examples of such wording: Portugal’s Public Water Domain Definition Law says only that access to the shore would be granted to the public [

28]. A somewhat more specific wording is found in Italy’s Financial and Budget Law, which requires that access to the maritime public domain be guaranteed in statutory plans for that domain [

33].

Although these examples of wording are rather general, embedding vertical accessibility rights in national-level legislation could, in principle, hold some legal weight when petitioners argue before the courts that vertical public access has not been adequately ensured.

Several countries have gone yet further and provide numeric standards. France’s national planning law stipulates that, if there is no public path within 500 m to reach the public domain, the local government

may create that path by imposing an easement over private property (with compensation). If needed, the local government has the powers to turn the path into a road [

32]. Spain and Greece adopted numeric standards too [

29,

35]. Spain’s legislation mandates that roads for vertical access be no more than 500 m apart and, unlike France, leaves little discretion to local government. In addition, in Spain, nonmotorised paths must be provided every 200 m.

In some jurisdictions, vertical access standards are to be implemented through demarcation of the access routes in local urban plans. An example is Greece, where, during a field research visit to the city of Kavala, we were shown the statutory plan. There, access roads or paths are delineated approximately 500 m apart [

55]. However, the authors of both the Spanish and the Greek chapters report that implementation of these standards falls below expectations [

29,

35]. Possible reasons are lack of funds to purchase or expropriate land or insufficient political will.

One can debate how realistic numeric standards imposed by national government are, and how locally democratic they are. However, they do represent attempts to provide some concrete norms. They are also easier for public interest groups to monitor and for the courts to review. In theory, quantitative norms may help to create greater social-distributive justice because they are expected to be blind to land prices and to the economic political influence of various interest groups.

Our comparative findings about vertical access, like horizontal access, indicate a positive momentum in some countries. Notably, in recent decades, Portugal’s 2005 legislation ambitiously requires that the areas where there are sandy beaches be made fully vertically accessible by 2016. We learn that some progress has indeed been made [

28].

By contrast, Malta’s jurisprudence is making it difficult for government authorities to progress towards vertical access rights. As noted earlier, the shoreline is already highly developed. Government has attempted to achieve incremental change to vertical access opportunities by conditioning new building permits (or retrospective legalisation permits) on provision of public access, but this has been ruled illegal by the courts. Xerri [

34] reports that, in a 2015 decision, the planning tribunal, while expressing some sympathy for both horizontal and vertical public access, saw no way of imposing such a condition under the existing legal framework:

“… no law can grant third parties rights on private property if not through the legal means which the legislator would have already put in place for such purpose. A policy certainly cannot, by itself, grant private property rights to third parties or be used to deny the development requested by an owner on his own land.”

(Victor Borg vs. Malta Environment and Planning Authority).

Unlike the other jurisdictions analysed here, Malta’s direction may be characterised as regressive. Yet, even within this country’s challenging legal and physical contexts, there is an increasing recognition of the importance of coastal access rights, especially within some local plans [

34].

8.4. The Issue of Private Fencing

Where vertical access rights cross private property, one of the major issues is illegal fencing or other physical obstacles intended to deter access. Tarlock [

25] reports of many court cases regarding obstacles or misleading signs placed by property owners, even in California, where, relative to other US states, beach access rights are better protected. The California Coastal Commission has the authority to impose high fines. An example is a 2021 court decision upholding a USD 4.2 million fine for fencing off a 1.5-m public easement to the beach continuously for 11 years [

56].

Several countries have deemed fencing to be important enough to scale it up from the local development permission level to the national or subnational level. However, “the devil is in the details”, and countries differ in what types of land uses they do permit to gate.

In Spain, Greece, Italy’s Puglia region, Turkey, and Denmark (to some extent), the legislation prohibits fencing within a specified distance from the shoreline—500 m in Spain and Greece, 300 m in Puglia, 100 m in Turkey, and 3 km in Denmark [

29,

31,

33,

35,

37]. In Greece, however, a presidential decree has gutted much of this rule by exempting a wide range of land uses, including tourist facilities, as explained by Balla & Giannakourou [

35].

Interestingly, in France, Prieur [

32] reports of the opposite approach. A 1986 amendment to the national planning law explicitly instructs local planning authorities to ensure that tourist and related commercial facilities approved near the coast do not block vertical access. One can assume that this legislation was not easy to enact because of its economic impacts on tourism projects. The conflict between tourism projects and vertical public access is a difficult one to balance, especially in countries such as Greece, where tourism is such a significant part of the economy.

Israel provides another example of fencing as a “red flag”. In this high-growth country, as noted earlier, the beaches are the most popular site of recreation, and crowding visibly increases annually. Environmental activists and enforcement authorities are especially engaged in monitoring any new fencing that curtails either horizontal or vertical access. The legislation now states that local authorities are no longer authorised to permit any fences in the coastal zone, except in special circumstances and with the permission of the national coastal regulatory committee [

38].

8.5. The Special Case of Gated Communities in Coastal Locations

When the practice of illegal fencing is carried out not just by individuals, but by “gated communities” along the coast, it may become an especially contested issue, with symbolic or direct implications for distributive justice. In some countries, such as the USA, gating is legal and rampant (not specifically on the coast [

57]). In many other countries, it is a de facto practice, even if unregulated or illegal [

58,

59]. In such cases, there is a double legal conflict with public accessibility: first, is it legal to gate residential neighbourhoods? Secondly, if gating is legal, do beach access rights override gating rights?

Within our study, the USA stands out because there are many gated communities along the coasts, and conflicts often reach the courts [

25,

60,

61]. In California, despite the Coastal Commission’s successes in providing for vertical public access to privately owned beaches, gated communities are a special challenge [

25]. In such cases, the blockage of public access may be more correlated with social exclusion.

Where gating is carried out by stealth, governments or the courts may find it even more difficult to enforce access rights. As noted by the Portuguese team, residents of quasi-gated communities sometimes use physical design or symbolic gating to signal “do not go through our property” [

28].

In Israel, the conflict between attempts to gate communities and coastal access has reached the courts. In two media-covered court challenges the petitions were triggered by the fact that the projects blocked coastal access. The court decisions became well-known rulings against neighbourhood gating in general [

38].

Enforcement of vertical access rights could be even more challenging where residential buildings or tourist facilities are entirely illegal [

62]. In this paper, we cover this complex topic only in passing (for detail, see [

63]). Such situations are not reserved for developing countries. Even within our sample countries—all with advanced economies—illegal construction along the coast is (or has been) especially rampant. These countries include Turkey, Italy, Malta, Greece, Slovenia, and Portugal (for Portugal, see also [

64]).

8.6. Ports as a Special Issue

Ports have good reasons to be located at and near the shoreline. National or regional legislation usually exempts them from enabling public access. Their premises have been tightly sealed off, even though they occupy hefty tracts of waterfront land. Due to increasing security needs (and international insurance requirements), ports have become even more locked in (Based on interviews with several port authorities in several countries, conducted during 2015, as part of the Mare Nostrum Project, ([

55], pp. 31–32)).

In recent years, citizen expectations and urban planning policies have succeeded in persuading port authorities in some cities to open up at least a small zone for public access to the waterfront. However, such retrofitting attempts are costly and are sometimes achieved through deals with private developers. Here is an example drawn from one of our research visits.

Figure 5 shows the only access point to the water at the Port of Marseilles (France). The port occupies a huge tract of the city’s urban coastal land but has developed one edge with a publicly accessible shopping mall. This large balcony overlooking the water’s edge is the closest that the public can get to the water and the only way to reach the balcony is to pass through the mall’s “golden cage” elevators or stairs (Based on an interview with the relevant officer of the Marseilles Port Authority, July 2015, and a personal visit to the Port and the shopping centre).

8.7. Summarizing Vertical Accessibility

The cross-national survey of vertical access rights exhibits a variety of approaches, similar to what we saw with horizonal access. The survey highlights some of the legal differences associated with the differing property right regimes. At the same time, one can point to a positive trend by which NGO initiatives reinforced by court decisions, coupled with the evolution of planning norms, has succeeded to some extent in overcoming entrenched conceptions of property rights.

9. Visual Accessibility

Visual accessibility is our third category of accessibility. It refers to unobstructed sightlines from the urban hinterland towards the coast. Protection of sightlines means, first and foremost, prevention of architectural configurations of large and tall structures close to the coastal area which block the sea view from city locations or routes. Since view of the coast is also a prime real-estate asset, intervention to enhance visual accessibility is likely to be resisted by developers or property owners.

Urban planning and design policies could contribute to greater fairness in the social distribution of coastal views. Ostensibly, this topic is remote from national-level policies. Yet, embedding the public right to visual access in a national-level law or policy document could encourage local efforts to address the social-distributive aspects of visual access. In our comparative analysis, we wanted to know whether visual access is regarded as part of the public right to coastal access and how national policy addresses it. The findings, as shown in

Table 1, indicate that, although this type of access right is not widely acknowledged, there are interesting exceptions. Perhaps they herald a rising legal recognition of visual access rights.

We were positively surprised that four of our jurisdictions already have explicit national or subnational provisions about protection of visual access to the coast, most introduced in recent years. These are Italy’s Puglia region, the Netherlands, Spain, and Israel. In California, visual access rights have been implemented in practice in some cases and have received scholarly analysis due to a major court decision (See discussion in

Section 7.1.3 about the US Supreme Court decision: Nollan v. California Coastal Commission).

Spain’s 1988 Coastal Law was the pioneer among our set. The Law stipulates that buildings constructed within 500 m of the shoreline should not form “architectural screens” that block views to the sea—that is, the wider façade should be perpendicular to the shoreline (interpretation of the law [

29]). As explained by Falco and Barbanente [

33], the Puglia’s Regional Landscape and Territorial Plan (2015) has added a prohibition on construction within 300 m of the shoreline that would reduce coastal views. Jong & van Sandick [

30] report that the Dutch General Spatial Planning Rules (2011) also require that a statutory land use plan approved at the local level should not enable construction that will obstruct the view of the horizon.

The latest to give explicit legal status to visual accessibility is Israel [

38]. The national statutory plan adopted in 2020 goes beyond a general normative statement to install a new mandatory procedure. In considering the merits of any proposed project within the coastal zone, the developer should submit a “view impact statement” (our translation) to the relevant planning body. Although it is too soon to know how the courts will interpret this requirement, one can assume that it will pave a smoother road for judicial review of planning decisions, which, according to the petitioners, assign insufficient weight to the public’s right to visual access. This innovation was stimulated by a court decision where a Tel Aviv NGO argued against approval of tall towers near the beach. The court ruled that the towers’ heights should be reduced to minimise obstruction of the coastal views.

So, while the right to visual coastal access is less recognised in national legislation than the first and second category, there are signals of an international positive moment.

We now move to the fourth (and final) category of accessibility rights, where social aspects are at the forefront.

10. Accessibility for People with Physical Disabilities

10.1. The Ratoinale for Assigning a Special Category

The fourth category of coastal access rights is less focused on broad geographic rules serving an anonymous public and more on the special needs of individuals. Making a beach site accessible to persons with physical disabilities (PWD) usually entails some special construction works (e.g., the interventions shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), adding a disruption of the beach environment to some degree. In the comparative research, we wanted to know whether and how the research jurisdictions have addressed the inherent normative conflict between environmental protection and the rights of PWD.

Beach access rights for PWD are not a marginal issue. An estimated 15% of the global population has a disability of some form, many of whom are persons with physical disabilities [

65]. A recent UN report reiterates the importance that national and local governments would increase their efforts to adjust public spaces and facilities to enable access by PWD [

66]. There is a large body of literature on this broad topic by researchers in the medical, socio-psychological, and design fields (see, for example, [

67,

68,

69]). There are even some papers about beach access for PWD written with tourism in mind [

70,

71]. Although many countries, including some in our sample, have general requirements about facilitating access to public spaces, these have yet to be adequately integrated into land use planning, as argued by Terashima and Clark [

72].

The comparative analysis indeed shows that, in most jurisdictions, beach access rights of PWD have not yet become part of the norms governing coastal land use planning and management in general, and accessibility in particular. Before we discuss the two national exceptions, we should note that the absence of national-level legislation does not imply that good practices cannot emerge “from below”, as part of the globally rising awareness of the rights of persons with disabilities. The Slovenian author, Marot [

36], provides an interesting example of how NGO action has managed to convince the City of Izola to pioneer in designating one of its beaches as accessible to PWD, with commensurate design and facilities. The city also waved the entrance fee, which it was permitted to charge for “special facilities”.

At the national level, the two notable exceptions are Italy’s Puglia region and Israel. Puglia’s Law of 2006 mandates that, when the Puglia Regional Government will prepare its Coastal Plan, the plan will ensure that local plans provide adequate access for people with disabilities [

33]. This is the pioneering legislative anchoring of this right among the jurisdictions in our sample.

10.2. Case Study of Jurisprudence on Beach Access Rights of PWD

In Israel, the 2004 Coastal Law is silent on this issue, but the new 2020 national plan includes distinct wording. Once again, the Israeli report highlights how NGO action and court decisions can lead the way [

38]. The jurisprudence on this issue provides an interesting legal manifestation of the clash between environmental protection and the rights of the disabled.

As noted in several places in the above discussion, in Israel, the role of court precedents, usually prompted by NGO actions, has played a prominent role in shaping coastal accessibility rights. In the case of PWD rights, the story is especially interesting due to a combination of circumstances.

By coincidence, two court cases regarding two adjacent cities (Tel Aviv and its neighbour Herzliya) were heard before the same district judge in 2013 and 2014. In one case, environmental NGOs petitioned against the city’s intention to extend a hard-surface promenade into the beach for a relatively short length. Part of the municipality’s rationale was that the surfacing would also facilitate wheelchair access. In this case, the judge ruled in favour of the city, despite the ambiguousness about whether the local plan permits the necessary public works. In her reasoning, the judge elaborated on the importance of social-distributive justice norms when considering the rights of persons with disabilities, because they are often deprived of public political influence. In the factual context of that case, she decided that the weight of these considerations over-rides environmental considerations.

However, in the second case brought before the same judge a while later, she ruled against the city, saying that, this time, environmental damage outweighs PWD accessibility rights. Indeed, in the second case, the proposed promenade was longer, but this fact does diminish the legal dilemmas that accompany such cases: how to balance two important public norms when they compete in specific, real-life situations?

With these precedential court decisions, Israeli planners and decision-makers went ahead to insert in the 2020 coastal national plan an explicit obligation to “take into account the needs of persons with disabilities”. Despite its vagueness, in some cases, such wording could, in theory, tip the balance when planning authorities or the courts must weigh environmental considerations against the rights of persons with physical disabilities. The sociological insight provided by the judge in the two court cases was instructive: environmental objectives, and the broad public and NGOs that support them, usually carry much more influence on public decision-making than do the small minority of physically disabled persons. Silence on this issue at the national level would leave the rights of PWD to local decisions, where there is usually an imbalance in the degree of influence on decision-makers.

11. Conclusions

Coastal zones are widely recognised as meriting special environmental protection, special modes of management (ICZM), and even have a unique standing in international law (though relevant only to some parts of the world). One would expect that the public’s right to access the beach would become the emblem of this special standing, but is it?

This paper presented a “reality check” through comparative analysis of the laws and regulations pertaining to coastal access rights in 15 advanced-economy countries. Eight of them are also members of the EU. To unpack the notion “coastal access”, we propose a conceptual framework that distinguishes among four categories: horizonal, vertical, visual, and accessible for persons with disabilities. This framework enables us to present a pioneering analysis that highlights the differences in legal and policy implications associated with each category. For each national (or state) jurisdiction, we rely on an expert report that analyses the relevant legislation and regulatory planning documents at the national level to see whether and how they address coastal access rights.

The emerging picture is of a clutter of types and degree of legal protection granted to coastal access rights. Even the international legislation (Mediterranean ICZM Protocol), which, in theory, applies to eight among the research countries, is shown to have only a marginal effect towards convergence. This is not benign diversity; it indicates that the international community—even among member of the OECD and members of the EU—is still a long way from elevating beach access rights into a consensual norm that is valid across borders.

At the same time, we do observe a trend in some countries towards enhancement of beach access rights. This momentum, however, is uneven across issues and countries. We believe that greater convergence could be promoted through cross-national learning. Our research—the first of its kind—could stimulate knowledge exchange.

Throughout this paper, we argued that the public right to access the beach (or the broader coastal zone) is not just a matter of geographic delineation of a strip of land along the beach, or demarcation of paths or roads to reach it from the hinterland. Our survey, spanning many different legal contexts, demonstrates that each of the four categories of coastal access rights invokes a somewhat different but deep-seated ideological debate about the role and limits of private property rights in the face of a consensual public good, such as beach access. The details of these conflicts are addressed differently in each country. We also highlighted that coastal accessibility is a social justice issue, with many facets.

Our comparative research, despite the large number of countries covered, is yet only a preliminary probe into the underlying implications of the different legal approaches to the right to coastal access and their outcomes in practice. There is room for much more comparative research, both legal and empirical. At the same time, one should keep in mind that coastal zones are experiencing accelerated change due to climate issues, and especially sea level rise. This implies that the rules about beach access rights are likely to require much rethinking. The need for international mutual learning will only increase.