Developing and Validating an Assessment Scale to Measure the Competitiveness of Wellness Destinations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Competitiveness in Economics and Management

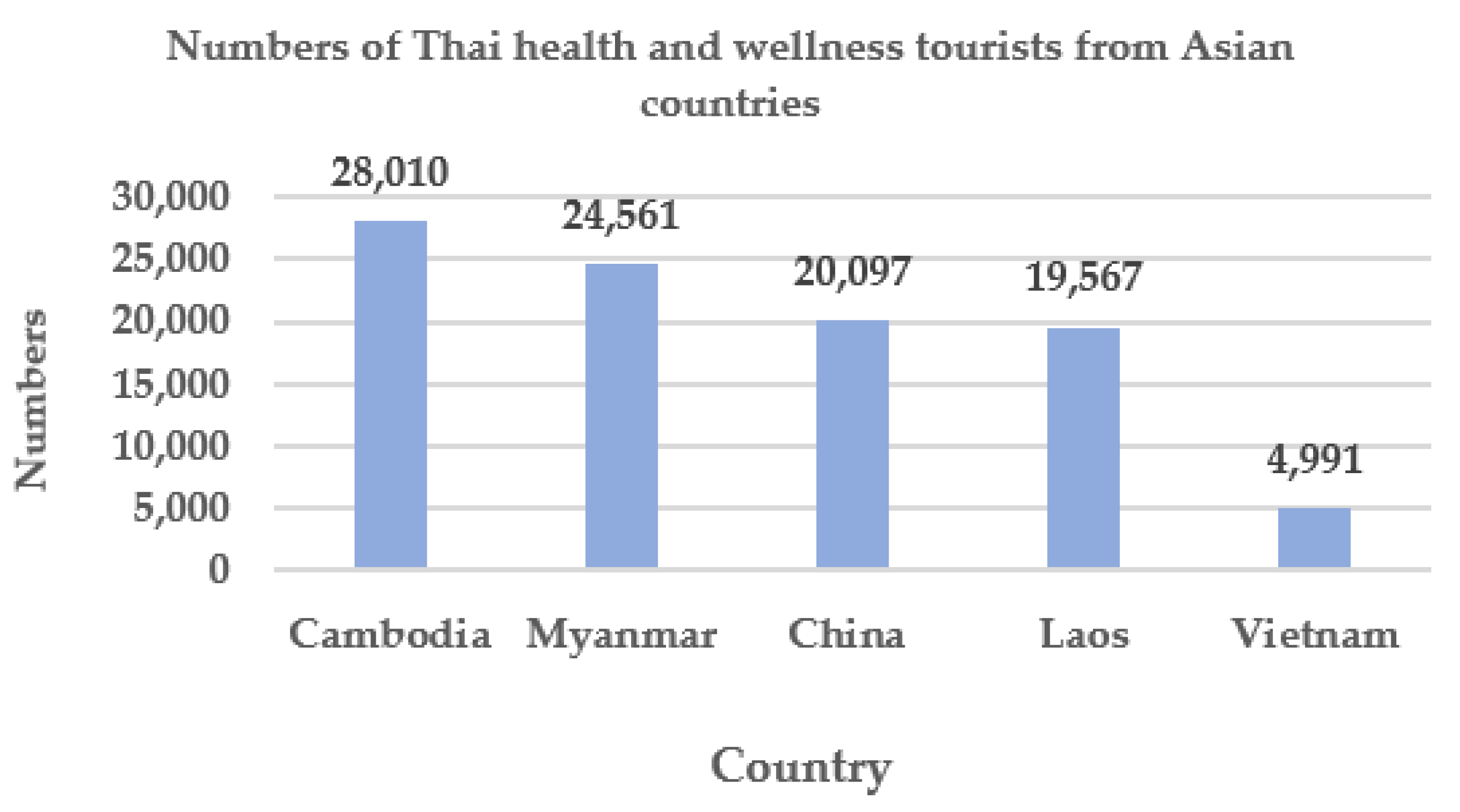

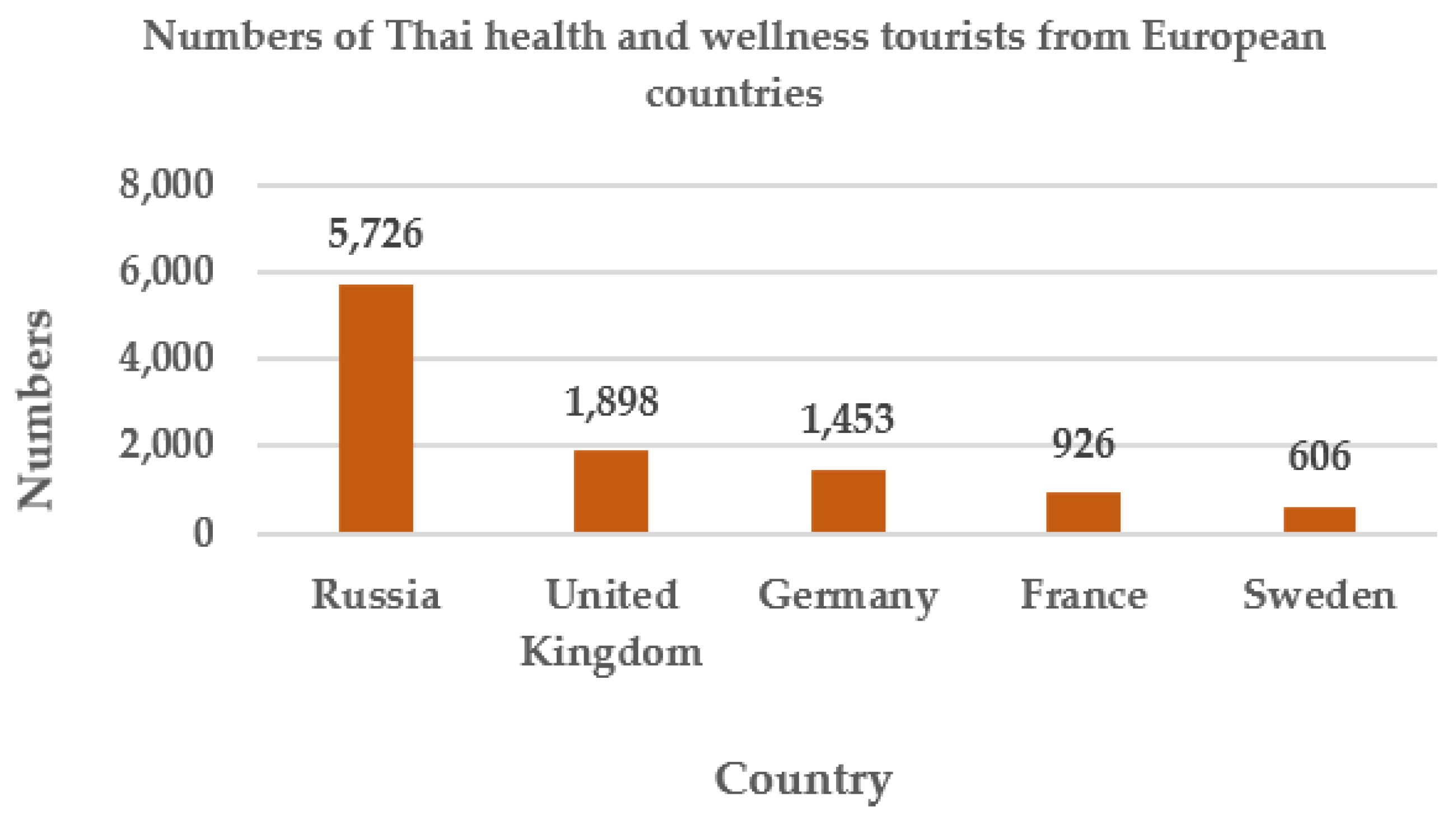

2.2. Dynamic Development of the Wellness Destination Market in Thailand

2.3. A Review of the Development and Validation of a Scale Studies

2.4. Measurements of Wellness Destination Competitiveness

2.4.1. Destination Environment

2.4.2. Wellness Tourism Travel and Policy

2.4.3. Wellness Tourism Infrastructure and Capacity

2.4.4. Wellness Tourism Man-Made and Cultural Resources

2.4.5. Wellness Tourism Strategy and Structure

2.4.6. Wellness Tourism Innovation Potential

2.4.7. Wellness Tourism Collaborative and Proactive Marketing

3. Methodology

Participants’ Rights Protection

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. General Data Analysis Regarding the Organization

4.2. Analysis of General Information Regarding the Questionnaire Respondents

4.3. Validation of the Measurement Scale

4.4. Descriptive Statistics

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion on the Final Model of the Wellness Destination Competitiveness Assessment Dimensions

5.2. Discussion on the Important of the Wellness Destination Competitiveness Dimensions and Each Factor of the Wellness Destination Competitiveness Measurement Scale

5.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code Name | Type | Gender | Experience (Year) | Education | Occupation | Duration (Min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA1 | Tourism administration | Female | 33 | Bachelor’s | Director | 48.05 |

| TA2 | Female | 29 | Master’s | Director | 51.49 | |

| TA3 | Female | 13 | Bachelor’s | Director | 72.10 | |

| TE1 | Tourism expert | Female | 27 | Ph.D. | Professor | 27.39 |

| TE2 | Male | 9 | Ph.D. | Professor | 96.45 | |

| TE3 | Female | 5 | Ph.D. | Lecturer | 48.45 | |

| TE4 | Female | 16 | Ph.D. | Lecturer | 76.27 | |

| TE5 | Male | 22 | Ph.D. | Professor | 49.28 | |

| TP1 | Tourism enterprise | Male | 25 | M.D. | Wellness tourism entrepreneur | 68.16 |

| TP2 | Female | 22 | Bachelor’s | Wellness tourism entrepreneur and Spa Developer | 101.50 | |

| TP3 | Male | 40 | Master’s | Wellness tourism entrepreneur | 95.03 | |

| TR1 | Tourist | Female | 5 | Master’s | Wellness traveler | 48.52 |

| TR2 | Female | 6 | Master’s | Wellness traveler | 57.22 |

References

- Yeung, O.; Johnston, K. Global Wellness Tourism Economy. 2018. Available online: https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/industry-research/global-wellness-tourism-economy/ (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Global Spa Summit & Stanford Research Institute International. Spas and the Global Wellness Market: Synergies and Opportunities. 2010. Available online: https://www.sri.com/publication/spas-and-the-global-wellness-market-synergies-and-opportunities/ (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- The Global Wellness Institute. The Global Wellness Tourism Economy 2013 & 2014. 2014. Available online: https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/GWI_2013_and_2014_Global_Wellness_Tourism_Economy_Report_Final.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- The Global Wellness Institute. Executive Summary. In The Global Wellness Economy. Global Wellness Economy Monitor October 2018; GWI: Miami, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The Global Wellness Institute. The Global Wellness Economy: Looking Beyond COVID. 2021. Available online: https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/GWI-WE-Monitor-2021_final-digital.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Chulalongkorn University Intellectual Property Institute. Trends Analysis Report on Technology and Affluent, Medical and Wellness Tourism Industry. 2017. Available online: https://www.ipthailand.go.th/images/3534/web_01052018/Report_CHU/8_Well-being_06.12.2017_CHU.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Teeranon, K. Thailand’s Wellness Tourism: Situation and Potential towards Competition of ASEAN Region. FEU Acad. Rev. J. 2018, 12, 22–34. Available online: https://so01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/FEU/article/view/109385/92255 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Kieanwatana, K. Situations and Trends of World and Thailand Health Tourism. J. Cult. Approach 2018, 19, 78–87. Available online: https://so02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/cultural_approach/article/view/123953 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Tourism and Sports. Tourism Economic Review; Permanent Secretary Ministry of Tourism and Sports: Bangkok, Thailand, 2016. (In Thai)

- Office of the National Economics & Social Development Board. The 12th National Economic and Social Development Plan (2017–2021); The Prime Minister’s Office All Rights Reserved: Bangkok, Thailand, 2016. (In Thai)

- Hudson, S.; Ritchie, B.; Timur, S. Measuring destination competitiveness: An empirical study of Canadian ski resorts. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2004, 1, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, T.; Saari, S.; Binder, D. Enhancing the competitiveness of a wellness tourism destination by coordinating the multiple actor collaboration. In The Routledge Handbook of Health Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.; Li, R.Y.; Huang, X. Sustainable Mountain-Based Health and Wellness Tourist Destinations: The Interrelationships between Tourists’ Satisfaction, Behavioral Intentions, and Competitiveness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Anjos, F.A.; Da Rosa, S. Measurement of competitiveness of nature-based tourist destinations: Application to national parks in brazil. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2021, 12, 1204–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas Fernández, J.A.; Serdeira Azevedo, P.; Martín Martín, J.M.; Rodríguez Martín, J.A. Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in the countries most visited by international tourists: Proposal of a synthetic index. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, L.; Kozak, M. Revisiting destination competitiveness through chaos theory: The butterfly competitiveness model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian Mosammam, H.; Sarrafi, M.; Nia, J. Measuring the competitiveness of Iran’s health tourism. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2019, 9, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalber, C.; Peters, M. Determinants of health tourism competitiveness: An Alpine case study. Tourism 2012, 60, 307–323. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim, A.H.; Ganguli, S. Strategic priorities for exploiting Bahrain’s medical tourism potential. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junio, M.M.V.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, T.J. Competitiveness attributes of a medical tourism destination: The case of South Korea with importance-performance analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, S.; Ebrahim, A.H. A qualitative analysis of Singapore’s medical tourism competitiveness. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 21, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, N.G.; Sakharchuk, E.S.; Ilkevich, S.V. The factors of Russia’s low competitiveness as a medical tourism destination. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 27, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hin, C.W.; Bohari, A.; Pu, L.T. An analysis of competitiveness of medical tourism in Malaysia and Thailand: A strategic management approach. Int. Bus. Manag. 2013, 7, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, D.; McIntosh, B. Using Authenticity to Achieve Competitive Advantage in Medical Tourism in the English-Speaking Caribbean. Third World Q. 2008, 29, 919–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.S.; Taghvaei, M. Medical tourism development determinants & strategies by taking an Approach towards Services Integration (Case study of tree health areas). J. Tour. Dev. 2021, 10, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-F.; King, B. A determination of destination competitiveness for Taiwan’s hot springs tourism sector using the Delphi technique. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-F.; King, B. Assessing Destination Competitiveness: An Application to the Hot Springs Tourism Sector. Tour. Hospit. Plann. Dev. 2006, 3, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Campón-Cerro, A.M.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Alves, H. Sustainable improvement of competitiveness in rural tourism destinations: The quest for tourist loyalty in Spain. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Ko, P.F.; Chiang, J.T. Developing an Evaluation Model for Monitoring Country-Based Tourism Competitiveness. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211047559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Almeida, D.; Gartner, W. Model konkurentnosti u turističkim destinacijama nematerijalne kulturne baštine sa stajališta temeljenog na znanju. Acta Tur. 2021, 33, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Müller, S.; Feiler, S. Destination competitiveness of winter sport resorts in the Alps: How sport tourists perceive destinations? Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Lo, M.-C.; Mohamad, A.A.; Wang, Y.-C.; Chin, C.-H. Booster of Rural Tourism’s Competitiveness: Stakeholders’ Involvement as a Moderator. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 539–546, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-González, R.; Swart, K.; Luque-Gil, A.M. Tourism competitiveness and sustainability indicators in the context of surf tourism: The case of Cape Town. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimpalee, J. The Expectations and Perceptions of Thai Tourists towards the Service Quality of Health Tourism Rommanee Hot Spring in Phangnga Province. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. Rajapruk Univ. 2021, 7, 246–262. Available online: https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/rpu/article/view/254792 (accessed on 9 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Kanittinsuttitong, N.; Lerdsakul, J. Market Demand and Capacity of Wellness Tourism in Nakhon si Thammarat Province. J. Soc. Sci. Buddh. Anthrop. 2021, 6, 77–93. Available online: https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JSBA/article/view/248436 (accessed on 9 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Peeraschaik, I.; Sangpikul, A. Tourist Experiences of Health Tourism at Natural Hot Springs Affecting Thai Tourists’ Satisfaction in Thong Pha Phoom, Karnchanaburi Province. J. Kanchanaburi Rajbhat Univ. 2021, 10, 223–234. Available online: https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/KRUjournal/article/view/246583/171198 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Siribowonphitak, C. Factors affecting revisiting of health tourists in Maha Sarakham province. Silpakorn Univ. J. 2021, 41, 37–50. (In Thai) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heranya, M. Wellness Tourism Behavior of Thai Tourists in Chiang Mai. Sarasatr 2021, 4, 664–677. Available online: https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/sarasatr/article/view/253309 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Thaotrakool, N.; Wannaluk, P. Guidelines for Marketing Communication Development of Health Tourismat Samoeng District and Mae-On District in Chiang Mai Province. Christ. Univ. Thailand J. 2020, 26, 72–83. Available online: https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/CUTJ/article/view/236377/165208 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Weerakit, N.; Poomaphinunt, P. Service Quality and Satisfaction of Chinese Wellness Tourists. J. Int. Stud. Prince Songkla Univ. 2020, 10, 29–52. Available online: https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jis/article/view/244381 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Soonthonsmai, V. A Causal Model of Satisfaction on Service Quality of Health Tourism in Scandinavian Aging Tourists in Thailand. Acad. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. Burapha Univ. 2020, 28, 244–268. Available online: https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/husojournal/article/view/195975/164328 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Chansiriwat, T. Need of Health Tourism Information in Thailand of Thai Tourists. J. Inf. Sci. 2019, 36, 1–17. Available online: https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jiskku/article/view/126736 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Pengthong, N. Factors that are Affecting the Health-Related Tourism to Foreign Tourists of Koh Samui District, Surat Thani Province. Pathumthani Univ. Acad. J. 2019, 11, 267–277. Available online: https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/ptujournal/article/view/187782 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Chatchawanchanchanakij, P.; Arpornpisan, P.; Chatchawanchanchanakij, K. Influence of Tourism Components on Health Tourism Image in Thailand. J. Interdiscip. Res. Grad. Stud. 2021, 10, 1–8. Available online: https://so03.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JIRGS/article/view/252755/170622 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Kupkitaphun, K.; Bunjongmanee, P. The Guidelines of Health Tourism Development of European Tourist in Prachuap Khiri Khan Province. J. Grad. Stud. Valaya Alongkorn Rajabhat Univ. 2020, 14, 1–13. Available online: https://so02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/JournalGradVRU/article/view/211712/163883 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Saynaratchai, K.; Kieanwatana, K.; Tuntate, U. The Development of Wellness Travel Programme for Tourist at Mae Sot Municipality in Tak Province. Inthaninthaksin J. 2020, 15, 59–91. Available online: https://so02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/HUSOTSU/article/view/246599/166909 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Boonchuai, J.; Dhamabutra, P. Strategic Plan for Integrated Sustainable Health Tourism Development in Bangkok, Thailand. Hum. Soc. Sci. Arts 2019, 12, 68–84. Available online: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/Veridian-E-Journal/article/view/146330 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Praprom, C.; Laipaporn, J. Probability Analysis of Wellness Tourism Service for Tourists Traveling in Betong District, Yala Province. Panyapiwat J. 2021, 13, 54–70. Available online: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/Veridian-E-Journal/article/view/146330/146936 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Nootayasakul, C.; Sungrugsa, N. Model of Human Resource Development in the Spa Business to Promote Wellness Tourism for Senior Tourists. Dusit Thani Coll. J. 2020, 13, 16–29. Available online: https://so01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/journaldtc/article/view/241090 (accessed on 23 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Wongprayoon, H.P.; Keadwichai, L.; Chancharoen, S. Management Factors Affecting to Health and Cultural Tourism Model in Khung Bang Kachao, Samut Prakarn Province. J. Assoc. Res. 2020, 25, 411–433. Available online: https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jar/article/view/247735/168194 (accessed on 9 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Leksuma, P.; Dokchan, T.; Udomsilp, M.; Fakyen, A.; Chuamuangphan, N. The Guideline of Wellness Tourism Activities Development in Western Thailand. Res. Dev. J. Loei Rajabhat Univ. 2019, 14, 20–30. Available online: https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/researchjournal-lru/article/view/207005/158969 (accessed on 9 January 2021). (In Thai).

- Dwyer, L.; Kim, C. Destination Competitiveness: Determinants and Indicators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.Q.; Dimmock, K.; Lohmann, G.; Scott, N. Destination competitiveness: How does travel experience influence choice? Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1673–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, O.; Yaskal, I. Theoretical Approaches to Concepts of “Competition” and “Competitiveness”. Ecoforum J. 2013, 2, 8–12. Available online: http://www.ecoforumjournal.ro/index.php/eco/article/viewFile/27/31 (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Boikova, T.; Zeverte-Rivza, S.; Rivza, P.; Rivza, B. The Determinants and Effects of Competitiveness: The Role of Digitalization in the European Economies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, S.; Sarıdoğan, E. The Effects of Science-Technology-Innovation on Competitiveness and Economic Growth. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, G.H.; Sima, V.; Nica, E.; Gheorghe, I.G. Measuring Sustainable Competitiveness in Contemporary Economies—Insights from European Economy. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badura, O.; Melecky, A.; Melecky, M. Liberalizing Passenger Rail: The Effect of Competition on Local Unemployment. 2022. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3954106 (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Przybyla, M.; Roma, M. Does Product Market Competition Reduce Inflation? Evidence from EU Countries and Sectors (March 2005). 2005. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.676404 (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Marketeer Online. Wellness Tourism: The Opportunity of Tourism Business. 2020. Available online: https://marketeeronline.co/archives/21776 (accessed on 12 March 2022). (In Thai).

- GlobalData Plc. Health and Wellness Tourism Trips to Asia to Reach 128.3 Million by 2022, Says GlobalData. 2020. Available online: https://www.globaldata.com/health-and-wellness-tourism-trips-to-asia-to-reach-128-3-million-by-2022-says-globaldata/ (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- The International Healthcare Research Center. This Destination is One of 46 Global Destinations Ranked Within the 2020–2021 Medical Tourism Index. Below is a Snapshot of This Destination’s Ranking. 2020. Available online: https://www.medicaltourism.com/destinations/thailand (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Ministry of Tourism and Sports. ASEAN Health Tourism 2012: Generates More than 2500 Million Baht in Current Income in Thailand. 2018. Available online: https://millionaire-academy.com/ (accessed on 12 March 2022). (In Thai)

- Kasikorn Research Center. Medical-Tourism Continued to Expand in 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www.kasikornbank.com/th/personal/the-wisdom/articles/e-newsletter/issue/2018/Pages/06.html (accessed on 12 March 2022). (In Thai).

- Department of International Trade Promotion, Ministry of Commerce. Elderly Tourist Market: New Thai Opportunities, Growing with AEC. 2014. Available online: https://ditp.go.th/contents_attach/87428/87428.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022). (In Thai)

- National Statistical Office. Number of Foreign Tourists Entering the Country Thailand Classified by Nationality 2009–2018. 2019. Available online: http://statbbi.nso.go.th/staticreport/page/sector/th/17.aspx (accessed on 12 March 2022). (In Thai)

- Chantaburee, S. Opportunity and Competitiveness of Spa and Thai Massage Businesses in Thailand. Kasem Bundit J. 2016, 17, 49–63. Available online: https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jkbu/article/view/69401 (accessed on 23 January 2022). (In Thai).

- Heesup, H.; Kiattipoom, K.; Heekyoung, J.; Wansoo, K. The role of wellness spa tourism performance in building destination loyalty: The case of Thailand. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 35, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieanwatana, K.; Sukonthasab, S.; Leemingsawat, W. Situations and Trends of World and Thailand Health Tourism. Acad. J. Ins. Phys. Educ. 2018, 10, 167–177. Available online: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/TNSUJournal/article/view/249220 (accessed on 23 January 2022). (In Thai).

- The International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Isaps International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.isaps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ISAPS-Global-Survey-Results-2018-1.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- World Economic Forum. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TTCR_2019.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Bangkokbiznews. World Organization Warns of ‘COVID-19’ a Major Economic Recession. 2020. Available online: https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/news/detail/874550 (accessed on 12 March 2022). (In Thai).

- Hinkin, T.R. A Review of Scale Development Practices in the Study of Organizations. J Manag. 1995, 21, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, R.L.; Whittaker, T.A. Scale Development Research: A Content Analysis and Recommendations for Best Practices. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, J.; Long, H. Understanding the Green Development Behavior and Performance of Industrial Enterprises (GDBP-IE): Scale Development and Validation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbing, D.W.; Anderson, J.C. An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment. J. Mark. Res. 1988, 25, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittamalla, R.; Srinivas Kumar, D.V. Determinants of holistic passenger experience in public transportation: Scale development and validation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, L.J.; Wright, A.G.C.; Cicero, D.; Kotov, R.; Mullins-Sweatt, S.N.; Sellbom, M.; Watson, D.; Widiger, T.A.; Zimmermann, J. Development of Measures for the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A Collaborative Scale Development Project. Assessment 2021, 29, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, N.M.; Hyde, J.S. The Objectified Body Consciousness Scale: Development and Validation. Psychol. Women Q. 1996, 20, 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogale, D.; Wondirad, A. Determinant factors of tourist satisfaction in Arbaminch City and its vicinity, Southern Ethiopia. Int. J. Tour. Policy 2019, 9, 320–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.; Perks, S. A dimensional framework of tourism indicators influencing destination competitiveness. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz Neto, A.; Lohmann, G.; Scott, N.; Dimmock, K. Rethinking competitiveness: Important attributes for a successful scuba diving destination. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2017, 42, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, M.H.; Ozturk, Y.; Karamustafa, K. A comparative perspective on destination competitiveness through visitors’ and stakeholders’ perceptions in the region of Cappadocia. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armis, R.; Kanegae, H. Regional competitiveness of a post-mining city in tourism: Ombilin coal mining heritage of Sawahlunto, Indonesia. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2021, 13, 1888–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milićević, S.; Petrović, J.; Kostić, M.; Lakićević, M. Tourism product in the function of improving destination competitiveness: Case of Vrnjačka Banja, Serbia. Qual.-Access Success 2020, 21, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Woyo, E.; Slabbert, E. Competitiveness factors influencing tourists’ intention to return and recommend: Evidence from a distressed destination. Dev. S. Afr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajić, T.; Penić, M.; Vujko, A.; Petrović, M.D. Development Perspectives of Rural Tourism Policy—A Comparative Study of Rural Tourism Competitiveness Based on Perceptions of Tourism Workers in Slovenia and Serbia. East. Eur. Countrys. 2018, 24, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, H.; Omar, B.; Mukhiar, S.N.S.; Park, O.; Zainol, W.W. Exploring Island Destination Competitiveness of Langkawi and Jeju UNESCO Global Geopark: Assessment from International Tourists and Tourism Practitioners. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.D.; Vujko, A.; Gajić, T.; Vuković, D.B.; Radovanović, M.; Jovanović, J.M.; Vuković, N. Tourism as an approach to sustainable rural development in post-socialist countries: A comparative study of Serbia and Slovenia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffi, G.; Cucculelli, M. Explaining tourism competitiveness in small and medium destinations: The Italian case. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2109–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.L.; Silva, R.; Patuleia, M.; Estêvão, J.; González-Rodríguez, M.R. Selecting lifestyle entrepreneurship recovery strategies: A response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; Patuleia, M.; Silva, R.; Estêvão, J.; González-Rodríguez, M.R. Post-pandemic recovery strategies: Revitalizing lifestyle entrepreneurship. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucci, A.C.; Moreno-Izquierdo, L.; Perles-Ribes, J.F.; Porto, N. Smart or partly smart? Accessibility and innovation policies to assess smartness and competitiveness of destinations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.W.; Li, C. The process of constructing a health tourism destination index. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardana, I.M.; Sukaatmadja, I.P.G.; Yasa, N.N.K.; Astawa, I.P. Cultural tourism and ecotourism empowerment in the sustainable tourism development and destination competitiveness enhancement. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2019, 10, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rojas, R.D.; del Río, J.A.J.; Fernández, A.I.; Vergara-Romero, A. The cultural and heritage tourist, SEM analysis: The case of The Citadel of the Catholic King. Herit. Sci. 2021, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Torres-Delgado, A.; Crabolu, G.; Palomo Martinez, J.; Kantenbacher, J.; Miller, G. The impact of sustainable tourism indicators on destination competitiveness: The European Tourism Indicator System. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenski, T.; Dwyer, L.; Pavluković, V. Destination Competitiveness: Public and Private Sector Tourism Management in Serbia. J. Travel Res. 2017, 57, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzhelele, T.W. An Assessment of the Potential of Hot Spring Tourism in Limpopo Province. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Venda, Limpopo, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, M.-C.; Chin, C.-H.; Law, F.-Y. Tourists’ perspectives on hard and soft services toward rural tourism destination competitiveeness: Community support as a moderator. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 19, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, O.T.; Monticelli, J.M.; Garrido, I.L.; Verschoore, J.R.; Henz, M. Achieving legitimacy of a film-tourism strategy through joint private–public policymaking. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slocum, S.L. The Influence of Government Controlled DMOs on Destination Competitiveness: The Case of Belarus. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topolansky Barbe, F.; Gonzalez Triay, M.; Häufele, C. The competitiveness of the Uruguayan rural tourism sector and its potential to attract German tourists. Compet. Rev. 2016, 26, 166–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafiah, M.H.; Zulkifly, M.I. Tourism destination competitiveness and tourism performance. Compet. Rev. 2019, 29, 592–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šajinović, S. Tourist destination branding in function of market positioning and increased competitiveness of spa tourism. Zb. Rad. Ekon. Fak. Istoč. Sarajev. 2016, 13, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, C.-K. Virtual travel experience and destination marketing: Effects of sense and information quality on flow and visit intention. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, A.; Buonincontri, P.; van Niekerk, M.; Orlowski, M.; Okumus, F. Exploring the role of next-generation virtual technologies in destination marketing. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Backman, K.F.; Backman, S.J.; Chang, L.L. Exploring the Implications of Virtual Reality Technology in Tourism Marketing: An Integrated Research Framework. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glyptou, K. Destination Image Co-creation in Times of Sustained Crisis. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 18, 166–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulou, E.; Al-Qasmi, I.; Melpignano, C. Co-creating Value in Desert Tourism Experiences. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 18, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddy, C.R. Sample size for qualitative research. Qual. Mark. Res. 2016, 19, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busser, J.A.; Shulga, L.V. Co-created value: Multidimensional scale and nomological network. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Bearden, W.O.; Sharma, S. Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rovinelli, R.J.; Hambleton, R.K. On the Use of Content Specialists in the Assessment of Criterion-Referenced Test Item Validity. Tijdschr. Voor Onderwijsres. 1977, 2, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, D.S. A-Priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models. 2021. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Harris, R.J. A Primer of Multivariate Statistics, 3rd ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baruch, Y.; Holtom, B.C. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relat. 2008, 61, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehlin, J.C. Latent Variable Model: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Analysis, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, R.O. Structural equation modeling: Back to basics. Struct. Equ. Model. 1997, 4, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types of Activities | Percentages of Expectations |

|---|---|

| Thai massage | 65.80 |

| Foot reflexology | 30.10 |

| Healthy eating | 29.50 |

| Aromatherapy massage | 26.80 |

| Yoga | 23.80 |

| Thai boxing | 22.30 |

| Meditation | 20.60 |

| Saunas | 16.60 |

| Compress massage | 13.80 |

| Stone massage | 13.60 |

| Taichi | 13.60 |

| Soaking in the jacuzzi pool | 13.00 |

| Acupressure massage | 11.00 |

| Hermit exercise (Rusie Dutton) | 8.20 |

| Mud-pack therapy | 6.70 |

| Dimension | Code | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Destination environment | DE1 | Business environment that promotes wellness tourism business |

| DE2 | Safety and security of the destination | |

| DE3 | Health and hygiene of the destination | |

| DE4 | Human resources in terms of staff in wellness tourism organizations and businesses that are responsible for delivering products and services to the tourists | |

| DE5 | Human resources in the area whose duty it is to welcome wellness tourists | |

| DE6 | Availability of information and communication technology | |

| Wellness tourism travel and policy | POL1 | Importance given to transportation, tourism, and health services |

| POL2 | Openness to international tourists to specifically promote wellness tourism | |

| POL3 | Ability to specify the price level of health promotion products and services | |

| POL4 | Environmentally friendly experience in the destination area | |

| Wellness infrastructure and capacity | INF1 | Infrastructure of transportation system that is ready to support wellness tourism |

| INF2 | Infrastructure to support services and tourism | |

| INF3 | Ability to accommodate tourists in terms of venues, accommodation, and facilities | |

| INF4 | Ability to accommodate tourists in terms of food and beverages | |

| INF5 | Ability to accommodate tourists in terms of recreation and entertainment | |

| Man-made and cultural resources | MAC1 | Readiness of semi-natural tourist attractions |

| MAC2 | Readiness of cultural and knowledgeable wisdom of tourist attractions | |

| MAC3 | Resources that are suitable for the development of tourist attractions, routes, or new activities to respond to wellness tourist needs | |

| MAC4 | Readiness of health promotion resources | |

| Wellness strategy and structure | WEL1 | Strategy to improve the quality of services and treatments |

| WEL2 | Promotion of tourist attractions as well-known and accredited | |

| WEL3 | Strategy planning for delivering services for customer satisfaction | |

| WEL4 | Link between different products, services, activities, and components of wellness tourism and tourists who visit the destination | |

| WEL5 | Health therapy and beauty activities offered by tourist attractions, such as healthy food, hot-spring bathing, steaming, water exercise, hydromassage, Thai massage, spas, Thai herbal steam, and acupuncture | |

| WEL6 | Tourist attractions offering physical wellness activities, such as yoga, sports tourism, cycling, and trekking | |

| WEL7 | Tourist attractions offering mental wellness activities, such as meditation, mind reading, Dharma practice, and mind-restorative activities | |

| WEL8 | Tourist attractions offering local knowledge learning activities, such as massage class, cooking class, local knowledge class, tour to learn local knowledge, market tour, and merit-making at temples. | |

| Innovation potential | INN1 | Knowledge to develop new products and services, including activities and components of wellness tourism, which are faster and of high quality |

| INN2 | Knowledge to respond to the needs of customers and tourists at the highest level | |

| INN3 | Human capital to develop new products and services, such as staff who are experts in wellness tourism and creative and passionate in developing new products and services, etc. | |

| INN4 | Openness to service innovation, such as application of electronic tourism system; acceptance of new technologies; and absorption, adjustment, and use of outside knowledge | |

| INN5 | Development of new wellness tourism services and products using local community resources based on outstanding local knowledge and identity | |

| Collaborative and proactive marketing | COL1 | Formation of cluster groups whose purpose is to work collaboratively and communicate with every group of stakeholders |

| COL2 | Creating opportunities and supporting local communities in participating in planning wellness tourism, such as health tourism programs or activities and local employment | |

| COL3 | Collaboration between public and private agencies | |

| COL4 | Marketing of health products and services with allies from public and private agencies at local, national, and international levels | |

| COL5 | Creating target brands attractive to tourists, such as outstanding presentation of slogans, logos, and health promotion services | |

| COL6 | Creating a more memorable brand identity than competitors’ | |

| COL7 | Links for advertising and publicizing together to market through health-based online social media platforms | |

| CO8 | Environmental simulation at real venues for targeted groups, customers, and interested people so they may experience, understand, and have clearer visualization of wellness tourism destination | |

| COL9 | Creating shareable feedback such as tourist feedback via online reviews and scores to evaluate customer satisfaction via online channels |

| Components | Indicators | Factor Loading | R2 | Construct Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destination environment (DE) | DE1 | 0.804 | 0.646 | 0.892 | 0.583 |

| DE2 | 0.853 | 0.728 | - | - | |

| DE3 | 0.803 | 0.645 | - | - | |

| DE4 | 0.711 | 0.505 | - | - | |

| DE5 | 0.768 | 0.590 | - | - | |

| DE6 | 0.618 | 0.381 | - | - | |

| Wellness tourism travel and policy (POL) | POL1 | 0.779 | 0.608 | 0.882 | 0.652 |

| POL2 | 0.856 | 0.732 | - | - | |

| POL3 | 0.816 | 0.667 | - | - | |

| POL4 | 0.777 | 0.603 | - | - | |

| Wellness infrastructure and capacity (INF) | INF1 | 0.679 | 0.461 | 0.852 | 0.536 |

| INF2 | 0.822 | 0.675 | - | - | |

| INF3 | 0.772 | 0.596 | - | - | |

| INF4 | 0.669 | 0.447 | - | - | |

| INF5 | 0.707 | 0.500 | - | - | |

| Man-made and cultural resources (MAC) | MAC1 | 0.725 | 0.525 | 0.793 | 0.500 |

| MAC2 | 0.694 | 0.482 | - | - | |

| MAC3 | 0.687 | 0.472 | - | - | |

| MAC4 | 0.693 | 0.480 | - | - | |

| Wellness strategy and structure (WEL) | WEL1 | 0.773 | 0.597 | 0.912 | 0.566 |

| WEL2 | 0.733 | 0.537 | - | - | |

| WEL3 | 0.732 | 0.536 | - | - | |

| WEL4 | 0.835 | 0.697 | - | - | |

| WEL5 | 0.732 | 0.536 | - | - | |

| WEL6 | 0.709 | 0.503 | - | - | |

| WEL7 | 0.791 | 0.626 | - | - | |

| WEL8 | 0.704 | 0.496 | - | - | |

| Innovation potential (INN) | INN1 | 0.901 | 0.485 | 0.937 | 0.749 |

| INN2 | 0.825 | 0.681 | - | - | |

| INN3 | 0.919 | 0.845 | - | - | |

| INN4 | 0.894 | 0.800 | - | - | |

| INN5 | 0.780 | 0.609 | - | - | |

| Collaborative and proactive marketing (COL) | COL1 | 0.911 | 0.527 | 0.955 | 0.703 |

| COL2 | 0.842 | 0.709 | - | - | |

| COL3 | 0.792 | 0.627 | - | - | |

| COL4 | 0.801 | 0.642 | - | - | |

| COL5 | 0.839 | 0.703 | - | - | |

| COL6 | 0.845 | 0.715 | - | - | |

| COL7 | 0.818 | 0.669 | - | - | |

| COL8 | 0.855 | 0.730 | - | - | |

| COL9 | 0.839 | 0.703 | - | - |

| AVE | DE | POL | INF | MAC | WEL | INN | COL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | 0.583 | 0.764 | ||||||

| POL | 0.652 | 0.402 | 0.807 | |||||

| INF | 0.536 | 0.422 | 0.460 | 0.732 | ||||

| MAC | 0.500 | 0.428 | 0.473 | 0.485 | 0.707 | |||

| WEL | 0.566 | 0.449 | 0.507 | 0.531 | 0.551 | 0.752 | ||

| INN | 0.749 | 0.375 | 0.465 | 0.471 | 0.477 | 0.527 | 0.865 | |

| COL | 0.703 | 0.363 | 0.430 | 0.424 | 0.448 | 0.498 | 0.517 | 0.838 |

| Dimension | Mean | S.D. | Rank | Indicators | Mean | S.D. | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative and proactive marketing (COL) | 4.57 | 0.508 | 1 | COL4 | 4.71 | 0.558 | 1 |

| COL8 | 4.64 | 0.570 | 2 | ||||

| COL3 | 4.61 | 0.597 | 3 | ||||

| INN5 | 4.59 | 0.591 | 4 | ||||

| COL9 | 4.59 | 0.550 | 4 | ||||

| COL2 | 4.56 | 0.624 | 6 | ||||

| Innovation potential (INN) | 4.51 | 0.545 | 2 | COL5 | 4.54 | 0.606 | 7 |

| INN3 | 4.53 | 0.607 | 8 | ||||

| INN4 | 4.52 | 0.617 | 9 | ||||

| COL6 | 4.51 | 0.617 | 10 | ||||

| COL7 | 4.49 | 0.617 | 11 | ||||

| INN2 | 4.49 | 0.654 | 12 | ||||

| Wellness tourism travel and policy (POL) | 4.29 | 0.572 | 3 | COL1 | 4.46 | 0.606 | 13 |

| INN1 | 4.44 | 0.651 | 14 | ||||

| POL1 | 4.38 | 0.624 | 15 | ||||

| WEL3 | 4.36 | 0.665 | 16 | ||||

| INF3 | 4.35 | 0.597 | 17 | ||||

| Wellness strategy and structure (WEL) | 4.19 | 0.552 | 4 | WEL8 | 4.35 | 0.645 | 18 |

| POL3 | 4.30 | 0.712 | 19 | ||||

| POL2 | 4.30 | 0.641 | 20 | ||||

| WEL6 | 4.26 | 0.607 | 21 | ||||

| WEL7 | 4.25 | 0.633 | 22 | ||||

| INF1 | 4.19 | 0.728 | 23 | ||||

| Wellness infrastructure and capacity (INF) | 4.16 | 0.550 | 5 | POL4 | 4.18 | 0.672 | 24 |

| WEL5 | 4.16 | 0.672 | 25 | ||||

| INF2 | 4.15 | 0.711 | 26 | ||||

| WEL4 | 4.14 | 0.706 | 27 | ||||

| INF4 | 4.10 | 0.648 | 28 | ||||

| MAC3 | 4.08 | 0.759 | 29 | ||||

| Man-made and cultural resources (MAC) | 4.03 | 0.602 | 6 | DE6 | 4.07 | 0.682 | 30 |

| MAC4 | 4.06 | 0.802 | 31 | ||||

| INF5 | 4.04 | 0.694 | 32 | ||||

| WEL2 | 4.02 | 0.711 | 33 | ||||

| MAC2 | 4.01 | 0.655 | 34 | ||||

| MAC1 | 3.98 | 0.699 | 35 | ||||

| Destination environment (DE) | 3.76 | 0.558 | 7 | WEL1 | 3.98 | 0.789 | 36 |

| DE3 | 3.84 | 0.698 | 37 | ||||

| DE2 | 3.81 | 0.633 | 38 | ||||

| DE1 | 3.77 | 0.645 | 39 | ||||

| DE5 | 3.64 | 0.726 | 40 | ||||

| DE4 | 3.42 | 0.726 | 41 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phuthong, T.; Anuntavoranich, P.; Chandrachai, A.; Piromsopa, K. Developing and Validating an Assessment Scale to Measure the Competitiveness of Wellness Destinations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074152

Phuthong T, Anuntavoranich P, Chandrachai A, Piromsopa K. Developing and Validating an Assessment Scale to Measure the Competitiveness of Wellness Destinations. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):4152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074152

Chicago/Turabian StylePhuthong, Thadathibesra, Pongpun Anuntavoranich, Achara Chandrachai, and Krerk Piromsopa. 2022. "Developing and Validating an Assessment Scale to Measure the Competitiveness of Wellness Destinations" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 4152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074152

APA StylePhuthong, T., Anuntavoranich, P., Chandrachai, A., & Piromsopa, K. (2022). Developing and Validating an Assessment Scale to Measure the Competitiveness of Wellness Destinations. Sustainability, 14(7), 4152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074152