Empirical Assessment and Comparison of Educational Efficiency between Major Countries across the World

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Super-SBM Model

2.2. The Malmquist Index Model

3. Variable Selection and Data Source

3.1. Variable Selection

- Input variables. (i), the total expenditure on education. It refers to the general expenditure (flow, capital, and transfer) of the government (district, regional, and central authority). It includes expenditures transferred from international funds to the government. The total government expenditure of a certain education level such as primary school, secondary school, higher education, or the sum of all education levels calculated in national currency reflects the total level of education expenditure of various countries. (ii), the total public expenditure on education per capita. It refers to the total expenditure of the government on student education from primary school to the completion/graduation of higher education. Due to different economic levels and population scales of various countries, the total public expenditure on education per capita reflects the level of education investment from an individual aspect. (iii), the proportion of total public expenditure on education in GDP. It reflects the different policies and attention of various countries to the education industry. Through the different proportions of public expenditure on education in GDP, it reflects the differences of input levels among countries in terms of financial resources/budgetary.

- Output variables. (i), the graduation rate of basic education. This refers to the percentage of students who have completed nine-year compulsory education in the relevant age group, which can reflect the level of basic education in a country; (ii), the achievements of higher education. It refers to the percentage of people who have received college or undergraduate education in the total population, which reflects the level of higher education in a country; (iii), the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores. PISA is a research project on the evaluation of 15-year-old students’ reading, mathematics, and science abilities carried out by the OECD [33]. Similarly, PISA assesses how far students near the end of compulsory education have acquired some of the knowledge and skills that are essential for full participation in society. Generally, the domains of reading and mathematical and scientific literacy are not merely covered in terms of mastery of the school curriculum, but in terms of important knowledge and skills needed in adult life [33]. Major countries in the world have participated in the evaluation. PISA can reflect the deficiency of the participant countries’ education efficiency according to the international comparison of students’ performance in PISA; therefore, this paper uses PISA score data to evaluate the quality and efficiency of a country’s education; (iv), the triadic patent families. A triadic patent family is defined as a set of patents registered in various countries (i.e., patent offices) filed at three of these major patent offices: the European Patent Office (EPO), the Japan Patent Office (JPO), and the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Innovation is one of the criteria to measure sustainable development. These patent families can well evaluate various countries’ innovation strength and thus reflect the ability of education to sustain development.

| Variable Descriptions | Variable Units | |

|---|---|---|

| Education investment index | Total public expenditure on Education | Million dollars |

| Total public expenditure on education per capita | Dollar | |

| Proportion of public expenditure on Education | Percentage of GDP | |

| Education output indicators | Graduation rate of basic education | Percentage of relevant age groups receiving full-time education |

| Achievements in Higher Education | Percentage of population with higher education | |

| PISA score | Test scores of 15-year-old students in reading, mathematics, and science | |

| Triadic patent families | Quantity |

3.2. Data Source

4. Analysis and Result of Educational Efficiency

4.1. Analysis of Educational Efficiency

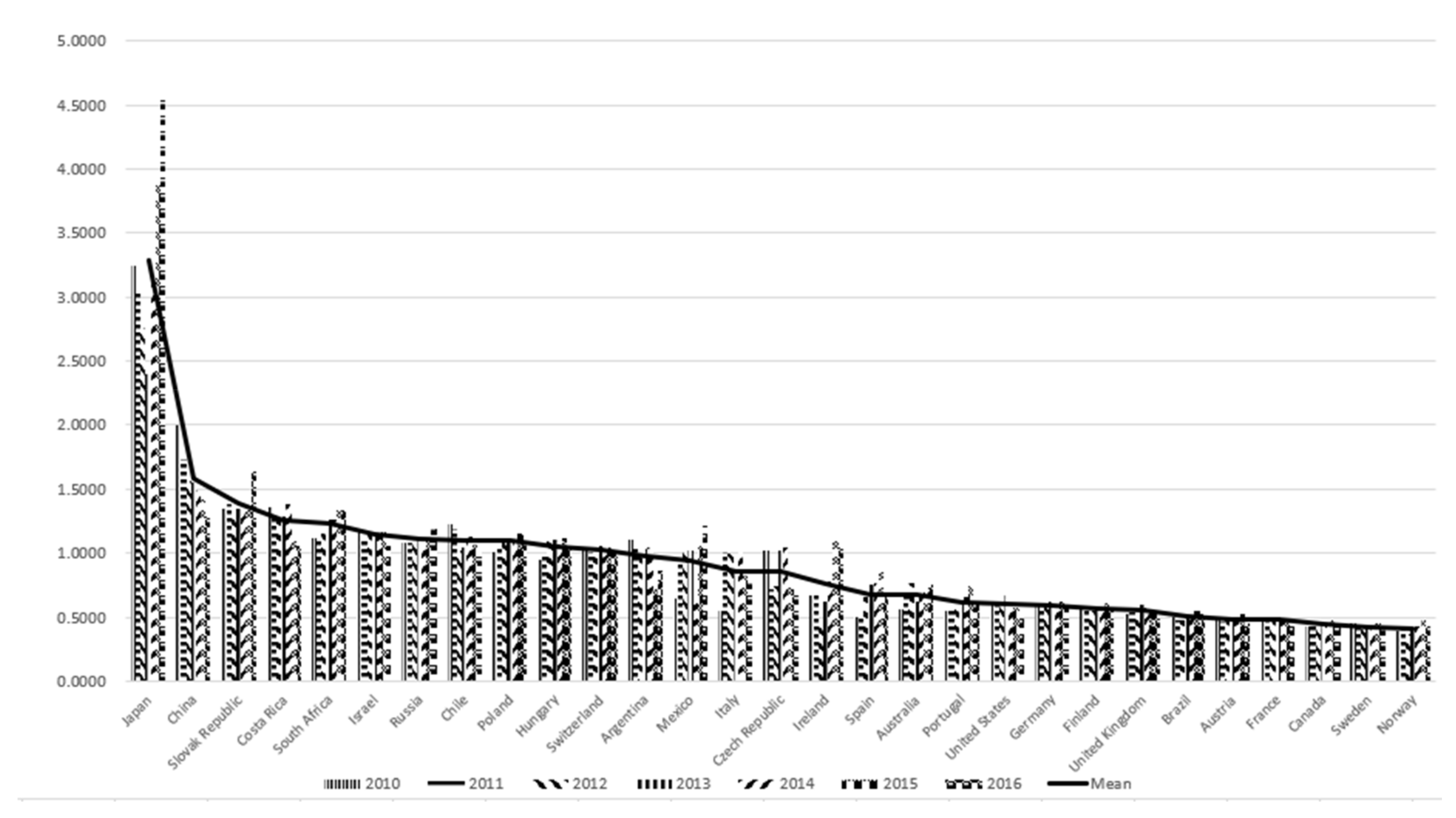

4.2. Assessment Result of Educational Efficiency in the World’s Major Economies

4.3. Decomposition Results of Malmquist Total Factor Productivity (TFP) Index

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- From the static analysis results, the overall education efficiency of the studied countries was in the DEA ineffective state. Except for 2011 and 2012, the education efficiency was gradually improving during the study period. Similarly, the educational efficiency of analyzed countries was mainly medium and high educational efficiency during the study period. In terms of years, the trend of transformation from low-efficiency countries to medium-high efficiency countries was slow. In addition, while ranking the educational efficiency of various countries based on the study result of the average efficiency over the years, this study observed that in addition to some developed countries, the educational efficiency of a number of developing countries was also at the forefront of technology. This study also discovered that there are huge differences in the level of educational efficiency among the investigated countries, and the development of the world educational level was quite unbalanced.

- (2)

- From the dynamic analysis results at the time series level, the overall education TPF index of major countries in the world shows a downward trend first and then an upward trend. The trend of techch was basically consistent with the trend of tfpch, and the pech and sech have also had varying degrees of impact on the education TPF index. Similarly, the average annual education of the investigated countries’ tfpch index was greater than 1 with an average annual growth of 0.4%, which demonstrated that the overall level of education efficiency shows an upward trend; however, the upward range has been relatively slow. The study discovers that technological progress was the main factor to promote the growth of education total factor productivity [42]. Moreover, during the study period, there were 17 countries with a mean value of the tfpch index greater than 1, which signifies that the overall TFP of education in these countries has been increasing. In particular, the mean value of Ireland’s TFP was 1.041, ranked first among 29 countries. Technical efficiency and technological progress were the major reasons for the increment of Ireland’s TFP. Except for the above 17 countries, the average tfpch index of other countries was less than 1, which discloses that the TFP of education in these countries had a downward trend and required improvement. Among them, China and Costa Rica have a large decline, with an average annual decline of 5.9% and 5.4% respectively. The decline of the techch index could be the primary reason for the decline of efficiency of education in these countries [4].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asongu, S.A.; Diop, S.; Addis, A.K. Governance, Inequality and Inclusive Education in Sub-Saharan Africa. Forum Soc. Econ. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytilova, H. The Causal Impact of Economic Education on Achievement of Optimum Outcomes. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 106, 2628–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ozturk, I. The Role of Education in Economic Development: A Theoretical Perspective. SSRN Electron. J. 2008, XXXIII, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, F. Measuring the Efficiency of Education and Technology via DEA Approach: Implications on National Development. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahnoun, M.; Abdennadher, C. Returns to investment in education in the OECD countries: Does governance quality matter? J. Knowl. Econ. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.; Zohlnhöfer, R. Investing in human capital? The determinants of private education expenditure in 26 OECD countries. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2009, 19, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffore, R.J.; Phenice, L.A.; Hsieh, M.-C. Trend Analysis of Educational Investments and Outcomes. J. Res. Educ. 2014, 24, 154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Miningou, E.W. Quality Education and the Efficiency of Public Expenditure: A Cross-Country Comparative Analysis; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, P.H. Occupation Aspirations, Education Investment, and Cognitive Outcomes: Evidence from Indian Adolescents. World Dev. 2019, 123, 104613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Equality of Educational Opportunity; U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Office of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- De Witte, K.; López-Torres, L. Efficiency in education: A review of literature and a way forward. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2017, 68, 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titus, M.A.; Eagan, K. Examining Production Efficiency in Higher Education: The Utility of Stochastic Frontier Analysis. In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research; Paulsen, M.B., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2016; pp. 441–512. [Google Scholar]

- Rządziński, L.; Sworowska, A. Parametric and Non Parametric Methods for Efficiency Assessment of State Higher Vocational Schools in 2009–2011. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2016, 4, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Izadi, H.; Johnes, G.; Oskrochi, R.; Crouchley, R. Stochastic Frontier Estimation of a CES Cost Function: The Case of Higher Education in Britain. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2002, 21, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnes, J. Data Envelopment Analysis and Its Application to the Measurement of Efficiency in Higher Education. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2006, 25, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibiano, P.; Agasisti, T. Efficiency of Public Spending in Education: A Challenge among Italian Regions. In Investigaciones de Economía de la Educación Volume 6; Caparrós Ruiz, A., Ed.; Asociación de Economía de la Educación: Zaragoza, Spain, 2011; Volume 6, pp. 503–516. [Google Scholar]

- Sibiano, P.; Agasisti, T. Efficiency and Heterogeneity of Public Spending in Education among Italian Regions. J. Public Aff. 2013, 13, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, M.S.; Dincă, G.; Andronic, M.L.; Pasztori, A.M. Assessment of the European Union’s Educational Efficiency. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnes, J.; Yu, L. Measuring the Research Performance of Chinese Higher Education Institutions Using Data Envelopment Analysis. China Econ. Rev. 2008, 19, 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guccio, C.; Martorana, M.F.; Monaco, L. Evaluating the Impact of the Bologna Process on the Efficiency Convergence of Italian Universities: A Non-Parametric Frontier Approach. J. Prod. Anal. 2016, 45, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başkaya, S.; Klumpp, M. International Data Envelopment Analysis in Higher Education: How Do Institutional Factors Influence University Efficiency? J. Bus. Econ. 2014, 5, 2085–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçin, S.; Tavşancil, E. The Comparison of Turkish Students’ PISA Achievement Levels by Year via Data Envelopment Analysis. Educ. Sci. Theory Pr. 2014, 14, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bagoury, S. Dea to Evaluate Efficiency of African Higher Education. Educ. Res. Essays 2013, 3, 742–747. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, W. The external social benefits of higher education: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. J. Educ. Financ. 2021, 46, 398. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.-B.; Lee, C. Data Envelopment Analysis. Stata J. 2010, 10, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Gamboa, M.; Iribarren, D. Coupled Life Cycle Thinking and Data Envelopment Analysis for Quantitative Sustainability Improvement. In Methods in Sustainability Science; Ren, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 295–320. [Google Scholar]

- Cova-Alonso, D.J.; Díaz-Hernández, J.J.; Martínez-Budría, E. A strong efficiency measure for CCR/BCC models. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 291, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. A Slacks-Based Measure of Efficiency in Data Envelopment Analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2001, 130, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. A Slacks-Based Measure of Super-Efficiency in Data Envelopment Analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 143, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelli, T.; Rao, D.S.P.; Battese, G.E. An Introduction to Efficiency and Productivity Analysis; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Malmquist, S. Index Numbers and Indifference Surfaces. Trab. Estad. 1953, 4, 209–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S.; Margaritis, D. Malmquist Productivity Indexes and DEA. In Handbook on Data Envelopment Analysis. International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Cooper, W.W., Seiford, L.M., Zhu, J., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 164, pp. 127–149. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 21st-Century Readers: Developing Literacy Skills in a Digital World; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Zhu, K.; Xu, J.; Meng, M. Sustainable development education from the perspective of China. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Information and Education Innovations—ICIEI 2019, Durham, UK, 10–12 July 2019; pp. 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, J.; Kruger, D. Science Education in South Africa. In Science Education in Countries along the Belt & Road: Future Insights and New Requirements; Huang, R., Xin, B., Tlili, A., Yang, F., Zhang, X., Zhu, L., Jemni, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Li, H.; Ali, R.; Rehman, R.; Fernández-Sánchez, G. Assessing the static and dynamic efficiency of scientific research of HEIs China: Three stage dea–malmquist index approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacovic, M.; Andrijasevic, Z.; Pejovic, B. STEM Education and Growth in Europe. J. Knowl. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abayasekara, A.; Arunatilake, N. School-Level Resource Allocation and Education Outcomes in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 61, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BenDavid-Hadar, I. Funding Education: Developing a Method of Allocation for Improvement. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2018, 32, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Zhou, Y. The Evaluation and Optimization to the Higher Educational Resource Allocation. Int. J. Cogn. Inform. Nat. Intell. 2015, 9, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Wang, Z.B.; Luo, D.; Wei, Y.; Sun, J. Synergy effects and it’s influencing factors of China’s high technological innovation and regional economy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Peng, L.; Shang, Y.; Zhao, X. Green technology progress and total factor productivity of resource-based enterprises: A perspective of technical compensation of environmental regulation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 174, 121276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristovnik, A. The Impact of ICT on Educational Performance and Its Efficiency in Selected EU and OECD Countries: A Non-Parametric Analysis. SSRN Electron. J. 2012, 11, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ghavifekr, S.; Rosdy, W.A.W. Teaching and Learning with Technology: Effectiveness of ICT Integration in Schools. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2015, 1, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnes, J.; Portela, M.; Thanassoulis, E. Efficiency in education. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2017, 68, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maradana, R.P.; Pradhan, R.P.; Dash, S.; Gaurav, K.; Jayakumar, M.; Chatterjee, D. Does innovation promote economic growth? Evidence from European countries. J. Innov. Entrep. 2017, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Continents | Countries | Developed | Developing | OECD | Non-OECD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | South Africa | √ | √ | ||

| America | Argentina | √ | √ | ||

| Brazil | √ | √ | |||

| Canada | √ | √ | |||

| Chile | √ | √ | |||

| Costa Rica | √ | √ | |||

| Mexico | √ | √ | |||

| United States | √ | √ | |||

| Asia | China | √ | √ | ||

| Japan | √ | √ | |||

| Israel | √ | √ | |||

| Australia | Australia | √ | √ | ||

| Eurasia | Russia | √ | √ | ||

| Europe | Austria | √ | √ | ||

| Czech Republic | √ | √ | |||

| Finland | √ | √ | |||

| France | √ | √ | |||

| Germany | √ | √ | |||

| Hungary | √ | √ | |||

| Ireland | √ | √ | |||

| Italy | √ | √ | |||

| Norway | √ | √ | |||

| Poland | √ | √ | |||

| Portugal | √ | √ | |||

| Slovak Republic | √ | √ | |||

| Spain | √ | √ | |||

| Sweden | √ | √ | |||

| Switzerland | √ | √ | |||

| United Kingdom | √ | √ |

| DMU | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Mean | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 1.1052 | 1.0396 | 1.0189 | 1.0330 | 1.0446 | 0.7237 | 0.8617 | 0.9752 | 12 |

| Australia | 0.5550 | 0.6673 | 0.7662 | 0.6182 | 0.6604 | 0.6990 | 0.7492 | 0.6736 | 18 |

| Austria | 0.4917 | 0.4698 | 0.4773 | 0.4923 | 0.4918 | 0.5242 | 0.4482 | 0.4850 | 25 |

| Brazil | 0.4985 | 0.4748 | 0.4722 | 0.4938 | 0.5092 | 0.5469 | 0.5232 | 0.5026 | 24 |

| Canada | 0.4317 | 0.4335 | 0.4267 | 0.4568 | 0.4576 | 0.4733 | 0.4473 | 0.4467 | 27 |

| Chile | 1.2213 | 1.1907 | 1.0216 | 1.0468 | 1.1332 | 1.0633 | 1.0209 | 1.0997 | 8 |

| China | 1.9954 | 1.7367 | 1.5578 | 1.5512 | 1.4898 | 1.4219 | 1.2858 | 1.5769 | 2 |

| Costa Rica | 1.3606 | 1.2964 | 1.2850 | 1.2886 | 1.3865 | 1.1227 | 1.0526 | 1.2561 | 4 |

| Czech Republic | 1.0213 | 0.7174 | 0.7470 | 1.0162 | 1.0398 | 0.7464 | 0.7229 | 0.8587 | 15 |

| Finland | 0.5737 | 0.5639 | 0.5518 | 0.5668 | 0.5760 | 0.6090 | 0.5569 | 0.5712 | 22 |

| France | 0.4978 | 0.4975 | 0.4792 | 0.4973 | 0.4819 | 0.4854 | 0.4259 | 0.4807 | 26 |

| Germany | 0.5839 | 0.5752 | 0.6005 | 0.6269 | 0.5972 | 0.6229 | 0.5696 | 0.5966 | 21 |

| Hungary | 0.9430 | 0.9768 | 1.0973 | 1.1074 | 1.0708 | 1.1186 | 1.0415 | 1.0508 | 10 |

| Ireland | 0.6754 | 0.6744 | 0.4665 | 0.6180 | 0.7799 | 1.1056 | 1.0398 | 0.7657 | 16 |

| Israel | 1.1741 | 1.1152 | 1.1705 | 1.1454 | 1.1735 | 1.1610 | 1.0594 | 1.1427 | 6 |

| Italy | 0.5502 | 1.0027 | 1.0016 | 0.8609 | 1.0126 | 0.8245 | 0.7669 | 0.8599 | 14 |

| Japan | 3.2452 | 3.0264 | 2.7579 | 2.3946 | 3.1131 | 3.8673 | 4.5872 | 3.2845 | 1 |

| Mexico | 0.6448 | 0.9376 | 1.0300 | 1.0218 | 0.6630 | 1.0528 | 1.2171 | 0.9382 | 13 |

| Norway | 0.3956 | 0.4007 | 0.3707 | 0.4016 | 0.4226 | 0.4787 | 0.4263 | 0.4137 | 29 |

| Poland | 1.0026 | 1.0317 | 1.1100 | 1.1073 | 1.1043 | 1.1575 | 1.1441 | 1.0939 | 9 |

| Portugal | 0.5513 | 0.5472 | 0.6152 | 0.6032 | 0.6621 | 0.7479 | 0.6160 | 0.6204 | 19 |

| Russia | 1.0775 | 1.0811 | 1.0971 | 1.1184 | 1.0799 | 1.1196 | 1.1906 | 1.1092 | 7 |

| Slovak Republic | 1.3475 | 1.3873 | 1.3018 | 1.3451 | 1.3208 | 1.3623 | 1.6321 | 1.3853 | 3 |

| South Africa | 1.1116 | 1.1114 | 1.1516 | 1.2625 | 1.2626 | 1.3766 | 1.3323 | 1.2298 | 5 |

| Spain | 0.4961 | 0.5011 | 0.6586 | 0.7542 | 0.7710 | 0.8480 | 0.6880 | 0.6739 | 17 |

| Sweden | 0.4508 | 0.4338 | 0.4004 | 0.4138 | 0.4183 | 0.4527 | 0.4189 | 0.4270 | 28 |

| Switzerland | 1.0148 | 1.0125 | 1.0167 | 1.0588 | 1.0415 | 1.0392 | 1.0210 | 1.0292 | 11 |

| United Kingdom | 0.5247 | 0.5311 | 0.5563 | 0.6020 | 0.5708 | 0.5337 | 0.5309 | 0.5499 | 23 |

| United States | 0.6038 | 0.6163 | 0.6230 | 0.6736 | 0.6082 | 0.5733 | 0.4922 | 0.5986 | 20 |

| Mean | 0.9015 | 0.8983 | 0.8907 | 0.9026 | 0.9291 | 0.9606 | 0.9610 | 0.9205 |

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of countries with high educational efficiency | 12 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Number of countries with middle educational efficiency | 11 | 11 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 11 |

| Number of countries with low educational efficiency | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Year | effch | techch | pech | sech | tfpch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010–2011 | 1.014 | 0.980 | 1.002 | 1.012 | 0.994 |

| 2011–2012 | 0.982 | 1.003 | 0.998 | 0.984 | 0.985 |

| 2012–2013 | 1.002 | 0.986 | 0.984 | 1.019 | 0.988 |

| 2013–2014 | 1.002 | 1.015 | 1.003 | 0.999 | 1.017 |

| 2014–2015 | 1.000 | 1.020 | 1.003 | 0.997 | 1.020 |

| 2015–2016 | 0.986 | 1.034 | 0.982 | 1.005 | 1.020 |

| Mean | 0.998 | 1.006 | 0.995 | 1.003 | 1.004 |

| Country | effch | techch | pech | sech | tfpch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 0.991 | 0.993 | 0.996 | 0.995 | 0.984 |

| Australia | 1.010 | 1.022 | 1.000 | 1.010 | 1.032 |

| Austria | 0.969 | 1.034 | 0.938 | 1.033 | 1.002 |

| Brazil | 1.040 | 0.990 | 1.019 | 1.021 | 1.029 |

| Canada | 0.987 | 1.007 | 0.984 | 1.003 | 0.993 |

| Chile | 1.000 | 0.960 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.960 |

| China | 1.000 | 0.941 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.941 |

| Costa Rica | 1.000 | 0.946 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.946 |

| Czech Republic | 0.980 | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.980 | 0.974 |

| Finland | 0.980 | 1.012 | 1.000 | 0.980 | 0.992 |

| France | 0.982 | 1.008 | 0.979 | 1.003 | 0.990 |

| Germany | 0.995 | 1.019 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 1.015 |

| Hungary | 1.005 | 0.988 | 1.000 | 1.005 | 0.993 |

| Ireland | 1.021 | 1.020 | 1.000 | 1.021 | 1.041 |

| Israel | 1.000 | 0.989 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.989 |

| Italy | 1.013 | 1.007 | 1.000 | 1.013 | 1.020 |

| Japan | 1.000 | 1.025 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.025 |

| Mexico | 1.029 | 1.010 | 1.021 | 1.008 | 1.039 |

| Norway | 0.978 | 1.018 | 0.981 | 0.997 | 0.996 |

| Poland | 1.000 | 1.028 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.028 |

| Portugal | 1.002 | 1.008 | 0.993 | 1.009 | 1.010 |

| Russia | 1.000 | 1.017 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.017 |

| Slovak Republic | 1.000 | 1.004 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.004 |

| South Africa | 1.000 | 1.025 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.025 |

| Spain | 1.021 | 1.019 | 1.019 | 1.002 | 1.040 |

| Sweden | 0.965 | 1.016 | 0.943 | 1.023 | 0.980 |

| Switzerland | 1.000 | 1.016 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.016 |

| United Kingdom | 0.989 | 1.033 | 0.992 | 0.996 | 1.022 |

| United States | 0.981 | 1.041 | 1.000 | 0.981 | 1.021 |

| Mean | 0.998 | 1.006 | 0.995 | 1.003 | 1.004 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Yu, Y.; Addis, A.K.; Guo, X. Empirical Assessment and Comparison of Educational Efficiency between Major Countries across the World. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074009

Chen L, Yu Y, Addis AK, Guo X. Empirical Assessment and Comparison of Educational Efficiency between Major Countries across the World. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074009

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Lipeng, Yang Yu, Amsalu K. Addis, and Xiao Guo. 2022. "Empirical Assessment and Comparison of Educational Efficiency between Major Countries across the World" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074009

APA StyleChen, L., Yu, Y., Addis, A. K., & Guo, X. (2022). Empirical Assessment and Comparison of Educational Efficiency between Major Countries across the World. Sustainability, 14(7), 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074009