Exploring Coastal Access in South Africa: A Historical Perspective

Abstract

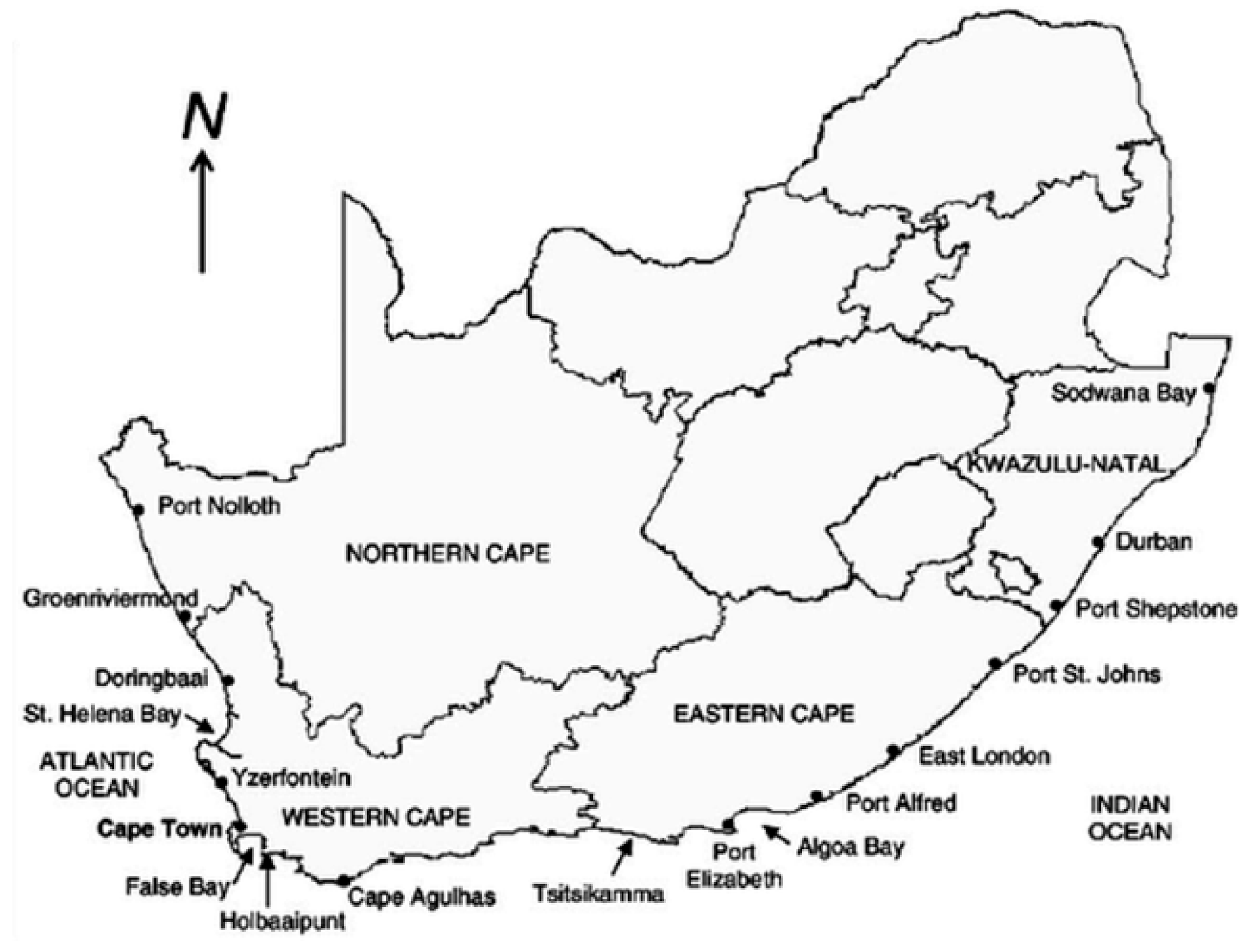

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Review of Historical Data Regarding Coastal Access in South Africa

3.1. Access to the Coast during the Pre-Colonial Era

3.2. Access to the Coast during the Colonial Era

3.3. Access to the Coast during Apartheid

3.4. Access to the Coast during a Democratic Period

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Willemse, M.; Goble, B.J. A Geospatial approach to managing coastal access in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. J. Coast. Res. 2018, 34, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goble, B.J.; Lewis, M.; Hill, T.R.; Phillips, M.R. Coastal management in South Africa: Historical perspectives and setting the stage of a new era. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 91, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guclu, K.; Karahan, F. A review: The history of conservation programs and development of the national parks concept in Turkey. Springer Link. Biodivers. Conserv. 2004, 13, 1373–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, M.C. History and Sustainable Development of Coastal Tourism in the City of Adana. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Coastal and Marine Tourism, İzmir, Turkey, 15–18 November 2005; pp. 434–444. [Google Scholar]

- Pakendorf, B.; Gunnink, H.; Sands, B.; Bostoen, K. ‘Prehistoric Bantu-Khoisan language contact’ A cross-disciplinary approach. Lang. Dyn. Chang. 2017, 7, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, E.; Oliver, W.H. The Colonisation of South Africa: A unique case. HTS Theol. Stud. 2017, 73, a4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, A. South Africa West Coast, History: The Forgotten People of the West Coast: Who Were the GuriQua? David Phillip Publishers (Pty) Ltd.: Cape Town, South Africa, 1998; Available online: http://www.sawestcoast.com/history.html (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Winton, J. ‘Proposal to United Nations on Behalf of the Republic of South Africa’ Legacy of Imperialism. 2011. Available online: https://m.sites.google.com/a/micds.org/legacy-of-imperialism-2011/oleski-s-classes/jeffrey-winton---south-africa (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Penn, N. The Forgotten Frontier, Colonist and Khoisan on the Cape’s Northern Frontier in the 18th Century; Ohio University Press: Athens, OH, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- WWF-SA. Oceans Facts and Futures: Valuing South Africa’s Ocean Economy; WWF-SA: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sunde, J.; Isaacs, M. ‘Marine Conservation and Coastal Communities: Who Carries the Costs?’ A Study of Marine Protected Areas and Their Impact on Traditional Small-Scale Fishing Communities in South Africa; International Collective in Support of Fishworkers: Chennai, India, 2008; Available online: https://aquadocs.org/handle/1834/19429 (accessed on 30 April 2008).

- Maneveldt, G.W. Keys to the non-geniculate coralline algae (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) of South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2008, 74, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I.D.; Hercus, L.; Kostanski, L. Indigenous and Minority Placenames: Australian and International Perspective; ANU Press, The Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J. Environment and Imperialism: Why Colonialism Still Matters; Sustainability Research Institute, School of Earth and Environment, The University of Leeds: Leeds, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- S.A. History Online. The Dutch and the Khoikhoi. 2017. Available online: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/dutch-and-khoikhoi (accessed on 22 May 2019).

- Marinda, W. Who Shaped South Africa’s Land Reform Policy? Politikon 2004, 31, 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, N. The Making of Modern South Africa: Conquest Segregation and Apartheid; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kloppers, I.H.J.; Pienaar, G.J. The historical context of land reform in South Africa and early policies. Potchefstroom Electron. Law J./Potchefstroomse Elektron. Regsblad 2014, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Durrheim, K.; Dixon, J. The role of place and metaphor in racial exclusion: South Africa’s beaches as sites of shifting racialization. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2001, 24, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandela, N. Long Walk to Freedom-Nelson Mandela; Macdonald Purnell (PTY) Ltd.: Randburg, South Africa, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tsabora, J. Land Redistribution Law and Environmental Justice in South Africa: An Analysis of South Africa’s Land Redistribution Law as a Means to Achieving Environmental Justice. SSRN Electron. J. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, G. Section 5 of the Black Administration Act: The Case of Bakwena ba Mogapa, No Place to Rest; Murray, C., O’Reagan, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fay, D. ‘Struggles over resources and community formation at Dwesa-Cwebe’ South Africa. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Manag. 2007, 3, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicomb, W. Rediscovering Community: The Dwesa-Cwebe Community; Legal Resources Centre (LRC): Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, J.M. Kicking Sand in the Face of Apartheid: Segregated Beaches in South Africa. Bull. Geogr. Socio–Econ. Ser. 2017, 35, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, V.; Homer-Dixon, T. Environmental scarcity and violent conflict: The case of South Africa. J. Peace Res. 1998, 35, 279–298. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/424937 (accessed on 10 May 2020). [CrossRef]

- Hersoug, B.; Holm, P. Change without redistribution: An institutional perspective on South Africa’s new fisheries policy. Mar. Policy 2000, 24, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, H.A.; King, N.D.; Fuggle, R.F.; Rabie, M.A. (Eds.) Environmental Management in South Africa; Juta & Co: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Emdon, L. Gender, Livelihoods and Conservation in Hluleka, Mpondoland c.1920 to the Present: Land, Forests and Marine Resources. Master’s Thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel, F.; Glazewski, J. The Oceans-Our Common Heritage. Going Green; Cock, J., Koch, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mwandla, N.D. Blacks and the Coast: Current Demands and Future Aspirations for Coastal Recreation in the KwaZulu-Natal North Coast. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zululand, Empangeni, South Africa, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Omond, O. The Apartheid Handbook; Penguin Books: Harmondsworth, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Chiba, Z. ‘Migrant in my own land’, on beach Apartheid: ‘Muizenberg beach with its shocking blue sea/sundrenched/but denied to me’. Sechaba 1975, 9, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Schensul, D. Remaking an Apartheid City, State-Led Spatial Transformation in Post-Apartheid Durban. Ph.D. Thesis, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Union of South Africa. The Reservation of Separate Amenities Act, Act No. 49 of 1953, Government Printer. Available online: http://psimg.jstor.org/fsi/img/pdf/t0/10.5555/al.sff.document.leg19531009.028.020.049_final.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2021).

- Horrell, M. A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa 1959–1960; South African Institute of Race Relations: Johannesburg, South Africa, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Fay, D.A. Post-Apartheid Transformations and Population Change around Dwesa-Cwebe Nature Reserve, South Africa. Conserv. Soc. 2011, 9, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, M. Individual transferable quotas, poverty alleviation and challenges for small-country fisheries policy in South Africa. MAST 2011, 2, 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Arnason, A. Efficient management of ocean fisheries. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1991, 35, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaila, U.R. A cautionary note on individual transferable quotas. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policy for the Small Scale Fisheries Sector in South Africa; Government Gazette No. 35455. Republic of South Africa Government: Cape Town, South Africa, 2012.

- Sowman, M.; Fuggle, R.; Preston, G. A review of the evolution of environmental evaluation procedures in South Africa. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1995, 15, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazewski, J. Environmental Law in South Africa; Butterworths: Durban, South Africa, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Glavovic, B. The evolution of coastal management in South Africa: Why blood is thicker than water. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2006, 49, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclennan, S. Land at Last! Community Celebrates Land Claim Success. Grocott’s Mail, 13 April 2018; Volume 148, Issue 014. Available online: https://grocotts.ru.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/13-April-2018.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Wren, W.S. South Africa Decide to Open All Beaches to Blacks. New York Times, 17 November 1989; A3. [Google Scholar]

- Goitom, H. On This Day: Desegregation of South African Beaches. In Global Law, Education; 16 November 2015. Available online: https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2015/11/on-this-day-desegregation-of-south-african-beaches/ (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- South Africa Government. National Environmental Management: Integrated Coastal Management Act 24 of 2008. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/national-environmental-management-integrated-coastal-management-act (accessed on 30 December 2008).

- Ngubane, S. Outcry Over Apartheid Beach Sign. Available online: https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/kwazulu-natal/outcry-over-apartheid-beach-sign-1863377 (accessed on 26 May 2015).

- Halvorsen, T.; Vale, P. (Eds.) One World, Many Knowledges: Regional Experiences and Cross-Regional Links in Higher Education; African Minds: Cape Town, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chutel, L. Seeing Black People Enjoying South Africa’s Beaches Still Isn’t a Normal Sight. It Should Be. Available online: https://qz.com/africa/879865/racial-tension-post-apartheid-still-flares-on-south-africas-beaches-with-black-people-flocking-to-the-countys-beaches/ (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Chutel, L. South Africa’s Beautiful Beaches Have an Ugly Problem of Racial Exclusion and Privatization. Available online: https://qz.com/africa/1516004/cape-towns-beach-racism-row-will-keep-happening/ (accessed on 6 January 2019).

- Lelyveld, J. Apartheid Is Crumbling on Beaches in South Africa; The Talk of Cape Town. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1981/03/12/world/apartheid-is-crumbling-on-beaches-in-south-africa-the-talk-of-cape-town.html (accessed on 12 March 1981).

- Andrew, W.K. America’s Segregated Shores: Beaches’ Long History as a Racial Battleground. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwi3tN74iJj2AhXrrlYBHTNeBpcQFnoECAcQAQ&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.kolumnmagazine.com%2F2018%2F06%2F12%2Famericas-segregated-shores-beaches-long-history-as-a-racial-battleground-the-guardian%2F&usg=AOvVaw2H5_WlnIlb7wYZLQ71njsT (accessed on 12 June 2018).

- Ministry of Environment and Tourism. Towards a Coastal Policy for Namibia: The Green Paper for the Coastal Policy of Namibia; Namibian Coast Conservation and Management (NACOMA): Swakopmund, Namibia, 2009.

- Cornelius, J.; Jordan, B. Apartheid Ways Die Hard on SA Beaches. Available online: https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2015-01-05-apartheid-ways-die-hard-on-sa-beaches/ (accessed on 5 January 2015).

- Haffajee, F.I. Swim Where I Like? Or Does Beach Apartheid Linger on? Available online: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-01-08-i-swim-where-i-like-or-does-beach-apartheid-linger-on/ (accessed on 8 January 2019).

- Van Heerden, O. The Unbearable Lightness of Being White in South Africa. Available online: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2019-01-08-the-unbearable-lightness-of-being-white-in-south-africa/ (accessed on 8 January 2019).

- Mutiga, M. South African Woman Faces Criminal Charges over Racist Tweets. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jan/05/south-african-woman-faces-criminal-charges-racist-tweets (accessed on 5 January 2016).

- Erasmus, Z. Contact Theory: Too Timid for “Race” and Racism. J. Soc. Issues 2010, 2, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of South Africa. State of the Oceans and Coasts around South Africa; Department of Environmental Affairs: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016.

- Sowman, M.; Malan, N. Review of progress with integrated coastal management in South Africa since the advent of democracy. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2018, 2, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Legislation | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| 1809 | Hottentot Proclamation | To control and limit mobility of labor force |

| 1879 | Native Location Act | To promote racial segregation |

| 1894 | Glen Grey Act | To create separate areas for Black people and directing their economic activities |

| 1913 | Native Land Act | To restrict Black people from buying and accessing land |

| 1927 | Black Administration Act | To ensure forceful removal of Africans from certain places including the coast |

| 1935 | The Sea Shore Act | Prohibiting Black people from settling near the high watermark of the coast and from using marine resources |

| 1950 | The Group Areas Act | Ensured that Caucasian people were exclusively located on the seaside and other prime lands |

| 1960 | Reservation of Separate Amenities Amendment Act | To implement beach discrimination and other forms of discrimination |

| 1988 | The Sea Shore Act | Ensured alienation of small-scale fisheries through the privatization of marine resources |

| 1989 | Environmental Conservation Act | To manage natural resources through a resource-centered approach and perpetuated racial exclusions |

| 1998 | National Environmental Management Act | To ensure equitable access to natural resources |

| 2008 | Integrated Coastal Management Act (ICM Act) | To address imbalances of the past pertaining to coastal resources |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mafumbu, L.; Zhou, L.; Kalumba, A.M. Exploring Coastal Access in South Africa: A Historical Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073971

Mafumbu L, Zhou L, Kalumba AM. Exploring Coastal Access in South Africa: A Historical Perspective. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073971

Chicago/Turabian StyleMafumbu, Luyanda, Leocadia Zhou, and Ahmed Mukalazi Kalumba. 2022. "Exploring Coastal Access in South Africa: A Historical Perspective" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073971

APA StyleMafumbu, L., Zhou, L., & Kalumba, A. M. (2022). Exploring Coastal Access in South Africa: A Historical Perspective. Sustainability, 14(7), 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073971