The Influence of Social Networks on the Digital Recruitment of Human Resources: An Empirical Study in the Tourism Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the impact of social media on the success of recruitment in tourism as a result of using a human resources digital strategy?

- Does the information search behavior and employment intention vary depending on the number of recommendations and the company’s reputation?

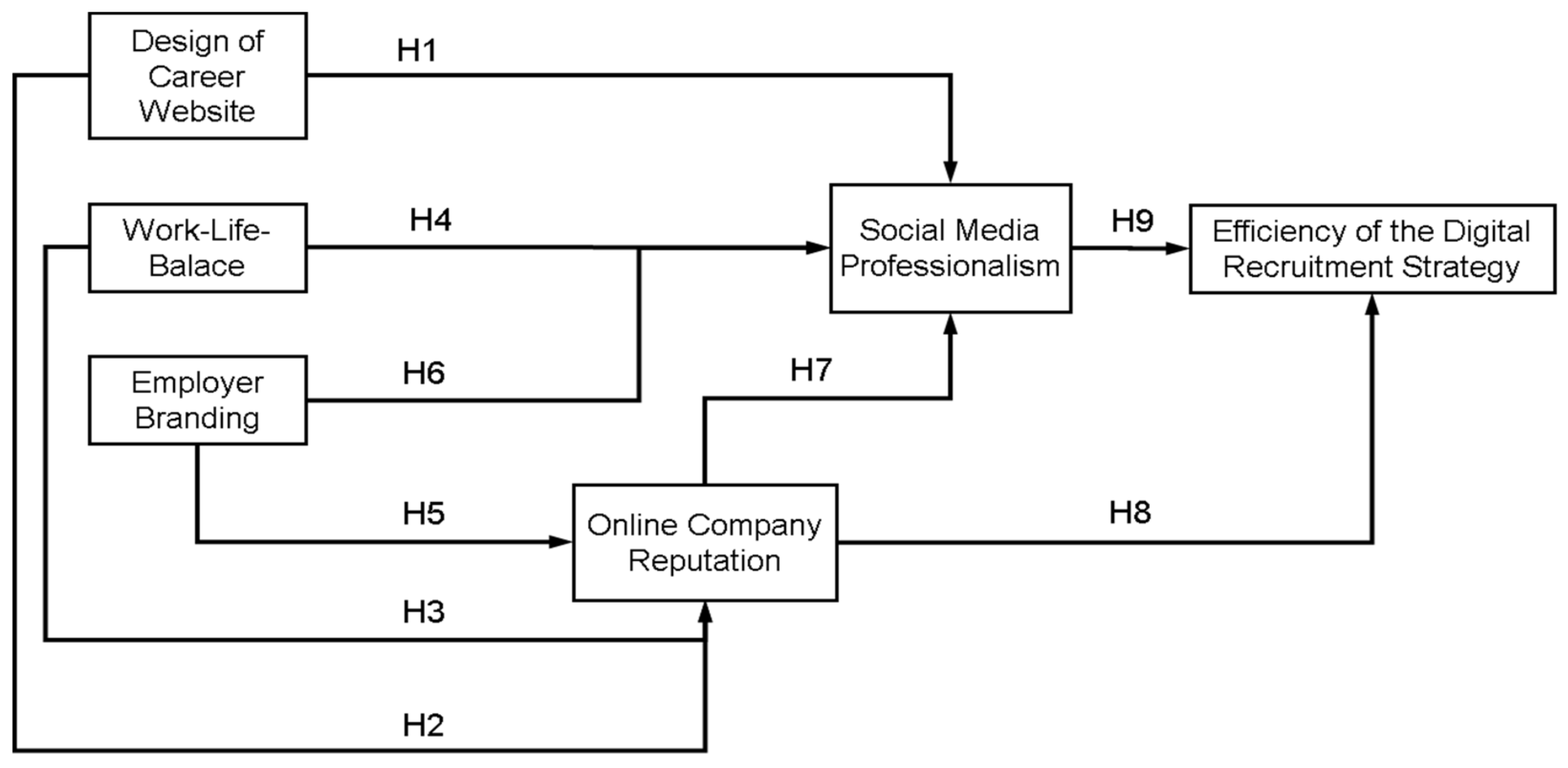

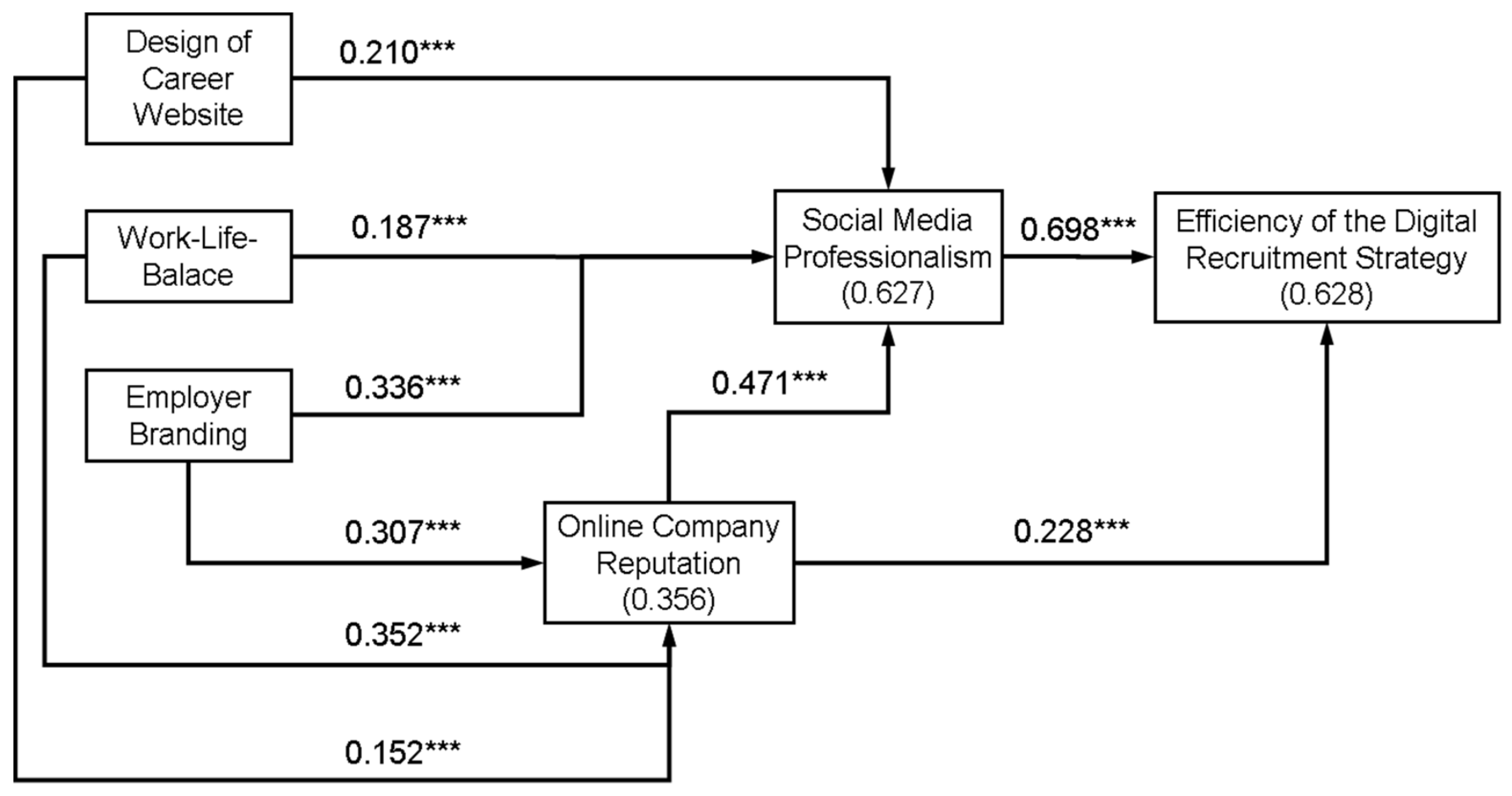

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Design of Career Website

2.2. Work–Life Balance

2.3. Employer Branding

2.4. Online Company Reputation

2.5. Social Media Professionalism

3. Research Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Limitations

6.2. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fossen, F.; Sorgner, A. Mapping the Future of Occupations: Transformative and Destructive Effects of New Digital Technologies on Jobs. Foresight STI Gov. 2019, 13, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groen, W.P.; Lenaerts, K.; Bosc, R.; Paquier, F. Impact of Digitalisation and the on Demand Economy on Labour Markets and the Consequences for Employment and Industrial Relations; European Economic and Social Committee: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Xue, Y.; Chen, H.; Ling, H.; Wu, J.; Gu, X. Making a Commitment to Your Future: Investigating the Effect of Career Exploration and Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy on the Relationship between Career Concern and Career Commitment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruël, H.J.M.; Bondarouk, T.V.; Van der Velde, M. The contribution of e-HRM to HRM effectiveness. Empl. Relat. 2007, 29, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier, S. Research in e-HRM: Review and implications. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2007, 17, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier, S. Digital human resource management: A conceptual clarification. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Z. Personalforsch. 2020, 34, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, E.; Mahmood, A.; Ahmad, N.; Ikram, A.; Murtaza, S.A. The Interplay between Corporate Social Responsibility at Employee Level, Ethical Leadership, Quality of Work Life and Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Case of Healthcare Organizations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waples, C.J.; Brachle, B.J. Recruiting millennials: Exploring the impact of CSR involvement and pay signaling on organizational Attractiveness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, J.E.; Cable, D.M.; Turban, D.B. Changing job seekers’ image perceptions during recruitment visits: The moderating role of belief confidence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettunen, J.; Sampson, J.P., Jr.; Vuorinen, R. Career practitioners’ conceptions of competency for social media in career services. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2015, 43, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, M.; Men, L.R.; O’Neil, J. Using Social Media to Engage Employees: Insights from Internal Communication Managers. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2019, 13, 110–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, B.; Santos, V.; Reis, I.; Sampaio, M.C.; Sousa, B.; Martinho, F.; Sousa, M.J.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Employer branding applied to SMEs: A pioneering model proposal for attracting and retaining talent. Information 2020, 11, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, D.R. Reactions to diversity in recruitment advertising–are differences black and white? J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Guo, X.; Luo, N.; Chen, G. Corporate blogging and job performance: Effects of work-related and nonwork-related participation. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2015, 32, 285–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarska, A.M.; Iwko, J. The Aspects of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Job Candidates’ Recruitment and Selection Processes in a Teal Organization. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Crotts, J.C. Theoretical models of social media, marketing implications, and future research directions. In Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality: Theory, Practice and Cases; Sigala, M., Christou, E., Gretzel, U., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Surrey, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, T.; Cheung, C.; Kong, H.; Kralj, A.; Mooney, S.; Nguyễn Thị Thanh, H.; Ramachandran, S.; Dropuli’c Ruži′c, M.; Siow, M. Sustainability and the Tourism and Hospitality Workforce: A Thematic Analysis. Sustainability 2016, 8, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimkiewicz, K.; Oltra, V. Does CSR enhance employer attractiveness? The role of millennial job seekers’ attitudes. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 49–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, F.; Reis, I.P.D.; Sampaio, M.C. Recruitment and Selection as a Tool for Strategic Management of Organizations–El Corte Ingles Case Study. J. Rev. Glob. Econ. 2019, 8, 1680–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Ohunakin, F.; Adeniji, A.A.; Ogunlusi, G.; Igbadumhe, F.; Salau, O.P.; Sodeinde, A.G. Talent retention strategies and employees’ behavioural outcomes: Empirical evidence from hospitality industry. Bus. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Bhatnagar, J.; Budhwar, P. Leveraging Social Networking for Talent Management: An Exploratory Study of Indian Firms. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 49, 630–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barykin, S.; Kalinina, O.; Aleksandrov, I.; Konnikov, E.; Yadikin, V.; Draganov, M. Personnel Management Digital Model Based on the Social Profiles’ Analysis. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.S.; Uggerslev, K.L.; Carroll, S.A.; Piasentin, K.A.; Jones, D.A. Applicant attraction to organizations and job choice: A meta-analytic review of the correlates of recruiting outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 928–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, X.; Lei, Z.; Lim, M.K. Social network analysis of sustainable human resource management from the employee training’s perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-C.; Shih, C.-T. How Executive SHRM System Links to Firm Performance: The Perspectives of Upper Echelon and Competitive Dynamics. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 853–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farndale, E.; Paauwe, J. SHRM and context: Why firms want to be as different as legitimately possible. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2018, 5, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Soria, J.A.; Ortega-Aguaza, B.; Ropero-García, M.A. Gender Segregation and Wage Difference in the Hospitality Industry. Tour. Econ. 2009, 15, 847–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawati, A.; Nurwati, N.; Suhana, S.; Machmuddah, Z.; Ali, S. Satisfaction, HR, and Open Innovation in Tourism Sector. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, J.-L.; González-Torres, T.; Montero-Navarro, A.; Gallego-Losada, R. Investing Time and Resources for Work–Life Balance: The Effect on Talent Retention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitz-Enz, J.; Mattox, J.R. Predictive Analytics for Human Resources; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thunnissen, M. Talent management: For what, how and how well? An empirical exploration of talent management in practice. Empl. Relat. 2016, 38, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier, S.; Kabst, R. Organizational adoption of e-HRM in Europe. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copley, P. Marketing Communications Management: Concepts and Theories, Cases and Practices; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethke-Langenegger, P.; Mahler, P.; Staffelbach, B. Effectiveness of talent management strategies. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2011, 5, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shet, S.V. Strategic talent management–contemporary issues in international context. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2020, 23, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnamara, J.; Zerfass, A. Social Media Communication in Organizations: The Challenges of Balancing Openness, Strategy, and Management. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2012, 6, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsetsura, K.; Kruckeberg, D. Transparency, Public Relations and the Mass Media: Combatting the Hidden Influences in News Coverage Worldwide; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nohria, N.; Groysberg, B.; Lee, L.-E. Employee Motivation: A Powerful New Model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Haddud, A.; Dugger, J.C.; Gill, P. Social Media for Organizations Exploring the Impact of Internal Social Media Usage on Employee Engagement. J. Soc. Media Organ. 2016, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Alshathry, S.; Clarke, M.; Goodman, S. The role of employer brand equity in employee attraction and retention: A unified framework. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2017, 25, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Deaton, A. High Income Improves Evaluation of Life but Not Emotional Well-Being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16489–16493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainable Human Resource Management: A Conceptual and Exploratory Analysis from a Paradox Perspective; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Physica-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Amundson, N.E. The influence of workplace attraction on recruitment and retention. J. Employ. Couns. 2007, 44, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-H. Electronic human resource management and organizational innovation: The roles of information technology and virtual organizational structure. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.H. Attract and retain top talent. Strateg. Financ. 2011, 92, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Breaugh, J.A.; Starke, M. Research on employee recruitment: So many studies, so many remaining questions. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathen, C.N.; Burkell, J. Believe It or Not: Factors Influencing Credibility on the Web. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2002, 53, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, M.; Buckley, K.; Paltoglou, G. Sentiment Strength Detection for the SocialWeb. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 63, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howieson, C.; Semple, S. The impact of career websites: What’s the evidence? Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2013, 41, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigurs, K.; Everitt, J.; Staunton, T. The Evidence Base for Careers Website. What Works? The Careers & Enterprice Company: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gunesh, P.; Maheshwari, V. Role of organizational career websites for employer brand development. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2019, 27, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, I. Social networking web sites in job search and employee recruitment. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2014, 22, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, M.; Kabst, R. The effectiveness of recruitment advertisements and recruitment websites: Indirect and interactive effects on applicant attraction. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoye, G.; Lievens, F. Investigating web-based recruitment sources: Employee testimonials vs word-of-mouse. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2007, 15, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Valcour, M.; Lirio, P. The Sustainable Workforce: Organizational Strategies for Promoting Work–Life Balance and Wellbeing. Work Wellbeing 2014, 3, 295–318. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A. The Psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, F.; Das, A.K. Work–Family Conflict on Sustainable Creative Performance: Job Crafting as a Mediator. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atan, A.; Ozgit, H.; Silman, F. Happiness at Work and Motivation for a Sustainable Workforce: Evidence from Female Hotel Employees. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, I.; Sousa, M.J.; Dionísio, A. Employer Branding as a Talent Management Tool: A Systematic Literature Revision. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G. Employer branding and its influence on managers. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronijević, A.; Janičić, R. Factors that influence cultural tourists to use e-WOM before visiting Montenegro. Ekonomika 2021, 67, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagirathi, M.M.; Magesh, D.R. Employer Branding Success through Social Media. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control. Syst. 2021, 11, 1556–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus, K.; Tikoo, S. Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career Dev. Int. 2004, 9, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W.F.; Graham, B.Z. New Strategic Role for HR: Leading the Employer-Branding Process. Organ. Manag. J. 2016, 13, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, N.L.; Sharma, S. Employer branding: Strategy for improving employer attractiveness. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2014, 22, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncioiu, I.; Popescu, D.-M.; Anghel, E.; Petrescu, A.-G.; Bîlcan, F.-R.; Petrescu, M. Online Company Reputation—A Thorny Problem for Optimizing Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Díaz, M.; Rodríguez-Voltes, C.I.; Rodríguez-Voltes, A.C. Gap Analysis of the online reputation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dramićanin, S.; Perić, G.; Pavlović, N. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment of employees in tourism: Serbian Travel agency case. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 26, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomir, L.; Plăias, I.; Nistor, V.C. Corporate online reputation, image and identity: Conceptual approaches. Mark. Inf. Decis. 2014, 7, 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Cian, L.; Cervai, S. Under the online reputation umbrella: An integrative and multidisciplinary review for corporate image, projected image, construed image, organizational identity, and organizational culture. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2014, 19, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaslan, Y.; Gülaçar, H.; Koç, M.N. User Profile Analysis Using an Online Social Network Integrated Quiz Game. J. Nat. Appl. Sci. 2017, 21, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Spector, P.E. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- King, K.A.; Vaiman, V. Enabling effective talent management through a macro-contingent approach: A framework for research and practice. Bus. Res. Q. 2019, 22, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikhamn, W. Innovation, Sustainable HRM and Customer Satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoll, J. Advertising in Social Media: A Review of Empirical Evidence. Int. J. Advert. 2015, 35, 266–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladkin, A.; Buhalis, D. Online and social media recruitment: Hospitality employer and prospective employee considerations. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarouali, B.; Poels, K.; Walrave, M.; Ponnet, K. ′You talking to me?′ The influence of peer communication on adolescents′ persuasion knowledge and attitude towards social advertisements. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 37, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Stylianou, A.C.; Zheng, Y. Sources and impacts of social influence from online anonymous user reviews. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, E.; Bozkurt, G.A. Hospitality Employees’ Future Expectations: Dissatisfaction, Stress, and Burnout. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2017, 18, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulou, K.; Mouratoglou, N.; Antoniou, A.S.; Mikedaki, K.; Charokopaki, A. Promoting Career Counselors’ Sustainable Career Development through the Group-based Life Construction Dialogue Intervention: “Constructing My Future Purposeful Life”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Vrontis, D.; Visser, M.; Stokes, P.; Smith, S.; Moore, N.; Thrassou, A.; Ashta, A. Talent management and the HR function in cross-cultural mergers and acquisitions: The role and impact of bi-cultural identity. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2021, 31, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.M.; Lance, C.E. What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.; MacKenzie, S.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items |

|---|---|

| Design of Career Website (DCW) [49,50,51,52,53,54] | (DCW1) The company has a career section on the site that is clearly distinguished from the other menu items. |

| (DCW2) The company offers on the site complete and updated information about vacancies and career opportunities. | |

| (DCW3) The company uses an applicant management system in which stakeholders can apply directly online. | |

| Work–Life Balance (WLB) [57,58,59] | (WLB1) Career planning in the company involves part-time work compatibility. |

| (WLB2) The company supports work–life balance and keeps its commitments. | |

| (WLB3) The flextime working model offered is attractive. | |

| Employer Branding (EB) [61,62,63,64,65,66,67] | (EB1) It matters that the company presents on social media the importance of the individual employee in the overall structure of the company. |

| (EB2) The presentation of the company’s benefits beyond just payment is important. | |

| (EB3) Companies that report on employee events are trusted. | |

| (EB4) The company that presented its values and philosophy in social media is appreciated. | |

| (EB5) It is important that employees have heard people talk about this employer’s branding. | |

| Online Company Reputation (OCR) [69,70,71] | (OCR1) The company treats customers and employees with respect. |

| (OCR2) The number of online recommendations is important when a person chooses to apply for a job. | |

| (OCR3) The company is a good employer and they stand out for the good treatment of employees. | |

| (OCR4) People apply for a job at a company that is recognized and strives to constantly improve. | |

| Social Media Professionalism (SMP) [73,74,75,76,77,78] | (SMP1) Comments on social media about the recruitment process are taken into account. |

| (SMP2) The company is constantly using social media profiles to draw attention to vacancies. | |

| (SMP3) The company provides detailed information about job offers on social networks. | |

| Efficiency of the Digital Recruitment Strategy (DHRS) [36,37,38] | (DHRS1) The proportion of people who did not stay in the company beyond the probationary period in the last 12 months is very small. |

| (DHRS2) The people the company has hired for the last 12 months fit very well within the advertised job. | |

| (DHRS3) In the last 12 months, the company has hired one of five candidates as a result of the digital recruitment process. |

| Variable | Constructs Items | Standard Deviation | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design of Career Website (DCW) | DCW 1 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.56 |

| DCW 2 | 0.98 | 0.76 | ||||

| DCW 3 | 0.93 | 0.77 | ||||

| Work–Life Balance (WLB) | WLB 1 | 0.94 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.58 |

| WLB 2 | 0.99 | 0.82 | ||||

| WLB 3 | 0.96 | 0.76 | ||||

| Employer Branding (EB) | EB 1 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.58 |

| EB 2 | 0.98 | 0.76 | ||||

| EB 3 | 0.80 | 0.75 | ||||

| EB 4 | 0.96 | 0.79 | ||||

| EB 5 | 0.98 | 0.88 | ||||

| Online Company Reputation (OCR) | OCR 1 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.60 |

| OCR 2 | 0.99 | 0.75 | ||||

| OCR 3 | 0.99 | 0.86 | ||||

| OCR 4 | 0.98 | 0.78 | ||||

| Social Media Professionalism (SMP) | SMP 1 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.57 |

| SMP 2 | 0.96 | 0.75 | ||||

| SMP 3 | 0.94 | 0.75 | ||||

| Efficiency of the Digital Recruitment Strategy (DHRS) | DHRS 1 | 0.98 | 0.74 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.55 |

| DHRS 2 | 0.93 | 0.75 | ||||

| DHRS 3 | 0.81 | 0.77 |

| WLB | OCR | EB | SMP | DCW | DHRS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WLB | 0.58 | |||||

| OCR | 0.43 | 0.60 | ||||

| EB | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.58 | |||

| SMP | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.36 | 0.57 | ||

| DCW | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.56 | |

| DHRS | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.55 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oncioiu, I.; Anton, E.; Ifrim, A.M.; Mândricel, D.A. The Influence of Social Networks on the Digital Recruitment of Human Resources: An Empirical Study in the Tourism Sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063693

Oncioiu I, Anton E, Ifrim AM, Mândricel DA. The Influence of Social Networks on the Digital Recruitment of Human Resources: An Empirical Study in the Tourism Sector. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063693

Chicago/Turabian StyleOncioiu, Ionica, Emanuela Anton, Ana Maria Ifrim, and Diana Andreea Mândricel. 2022. "The Influence of Social Networks on the Digital Recruitment of Human Resources: An Empirical Study in the Tourism Sector" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063693

APA StyleOncioiu, I., Anton, E., Ifrim, A. M., & Mândricel, D. A. (2022). The Influence of Social Networks on the Digital Recruitment of Human Resources: An Empirical Study in the Tourism Sector. Sustainability, 14(6), 3693. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063693