Does Job Satisfaction Differ at Different Levels of Employees? Measurement of Job Satisfaction among the Levels of Sugar Industrial Employees

Abstract

1. Introduction

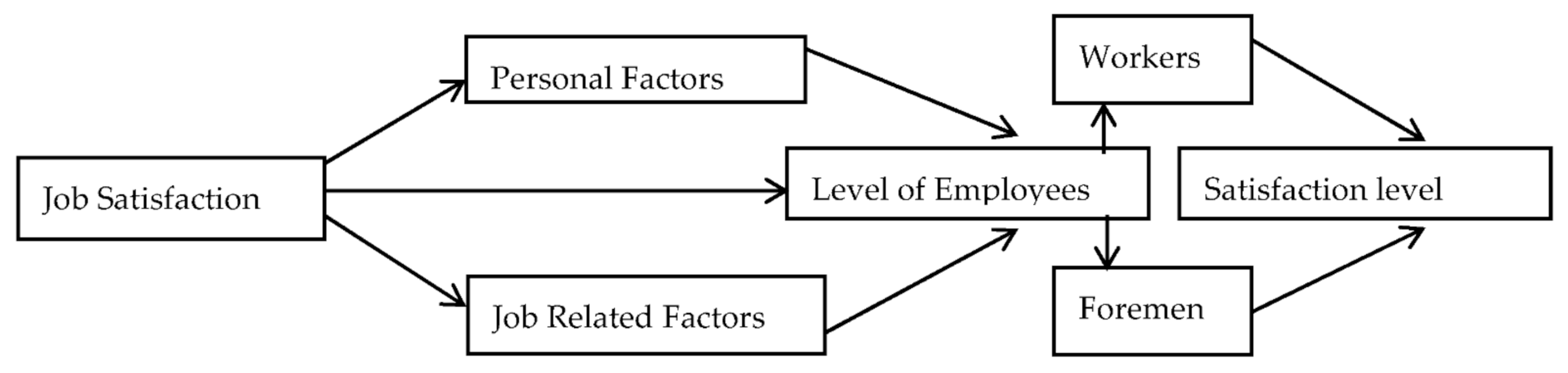

- To compare the overall job satisfaction between workers and foremen of sugar industrial workers in Bangladesh;

- To examine the level of satisfaction of specific personal and job-related factors perceived by workers and foremen.

2. Literature Review

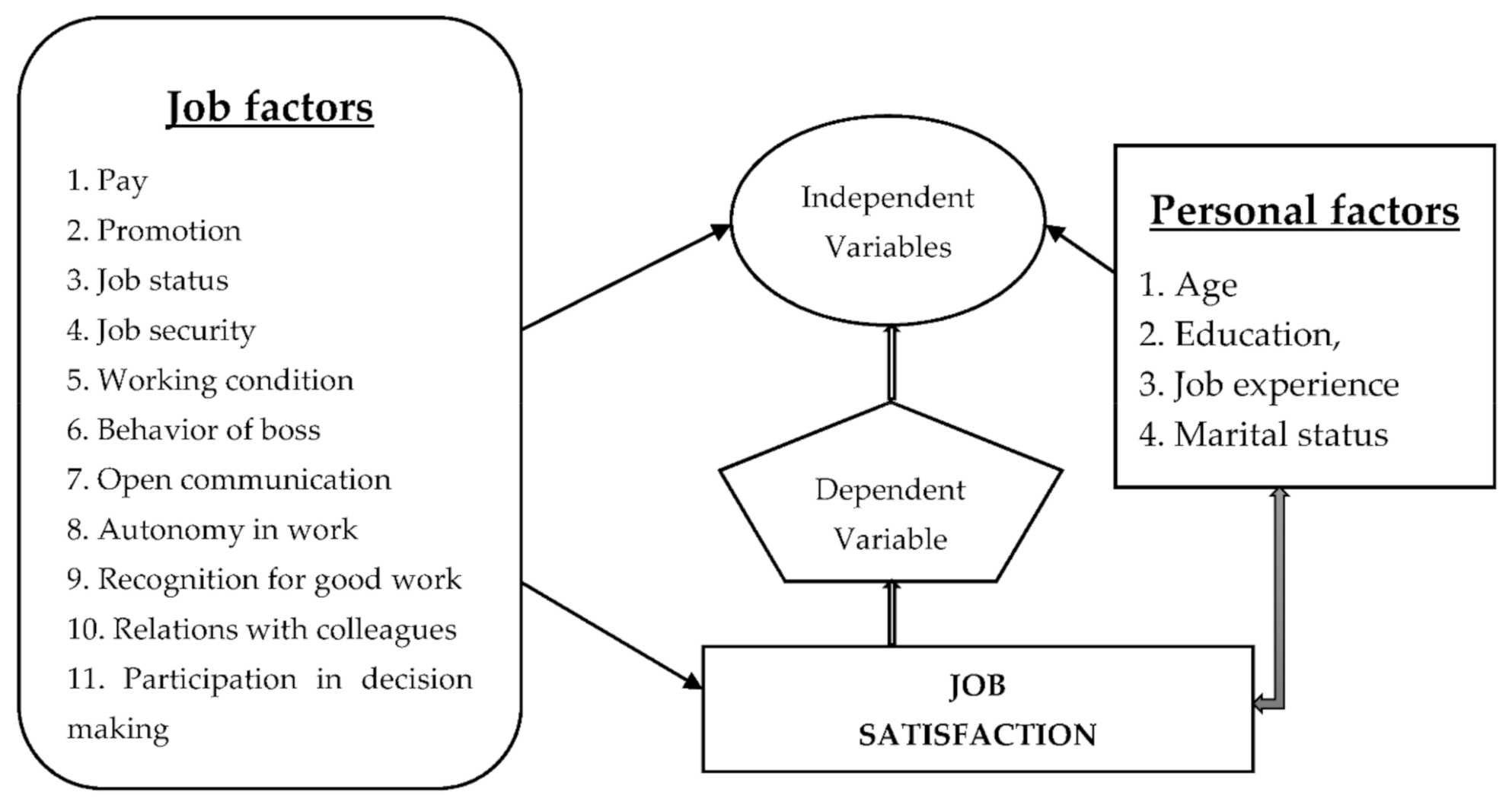

2.1. Job Satisfaction, Personal Factor, and Job Facet Perspectives

2.2. Job Satisfaction and Levels of Employee Perspectives

3. Methodology of the Study

3.1. Survey Administration and Sample

3.2. Operationalization of Constructs

3.3. Conceptual Framework of the Study

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Statistical Assessment and Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lange, T. Job Satisfaction and Implications for Organizational Sustainability: A Resource Efficiency Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongo, J.S.; Tesha, D.N.G.A.K.; Kasonga, R.; Luvara, V.G.M.; Mwanganda, R.J. Job Satisfactions of Quantity Surveyors in Building Construction Firms in Dar-Es-Salaam, Tanzania. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Res. 2019, 9, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazi, M.A.I. Job satisfaction of Bangladesh sugar mills workers regarding some job facets: A case study on Carew & Co (BD) Ltd. Int. J. Inf. Bus. Manag. 2021, 2, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppock, R. Job Satisfaction; Harper and Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Gazi, M.A.I.; Rahaman, M.A.; Hossain, G.M.A.; Ali, M.J.; Mamoon, Z.R. An empirical study of determinants of customer satisfaction of banking sector: Evidence from Bangladesh. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Cheng, J.; Hale, C.L. Workplace Emotion and Communication: Supervisor Nonverbal Immediacy, Employees’ Emotion Experience, and Their Communication Motives. Manag. Commun. Q. 2017, 31, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Pu, B.; Guan, Z. Entrepreneurial leadership and turnover intention in startups: Mediating roles of employees’ job embeddedness, job satisfaction and affective commitment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, M.A.; Jorge, A.G.; Wang, Y. Job flexibility and job satisfaction among Mexican professionals: A socio-cultural explanation. Empl. Relat. 2018, 40, 921–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.N.I.; Sultana, A.; Prodhan, A.Z.M.S. Job satisfaction of employees of public and private organizations in Bangladesh. J. Political Sci. Public Int. Aff. 2017, 1, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuzzaman, M. Determinants of Job Satisfaction of Garment Employees. Int. J. Multi-Dimens. Res. 2017, 5, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Mesurado, B.; Crespo, R.; Rodriguez, O.; Debeljuh, P.; Idrovo, S. The development and initial validation of the multidimensional flourishing scale. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariam, S. Job Satisfaction Employees Hospital. Bus. Entrep. Rev. 2019, 19, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Santhoshkumar, G.; Jayanthy, S.; Velanganni, R. Employees Job Satisfaction. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control Syst. 2019, 11, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Thant, Z.M.; Chang, Y. Determinants of Public Employee Job Satisfaction in Myanmar: Focus on Herzberg’s Two Factor Theory. Public Organiz. Rev. 2021, 21, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh-Quang, D. The Effects of Demographic, Internal and External University Environment Factors on Faculty Job Satisfaction in Vietnam. J. Educ. Issues 2016, 2, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, N.H.; Jumani, N.B. Relationship of job satisfaction and turnover intention of private secondary school teachers. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahaan, E. Can We Rely on Job Satisfaction to Reduce Job Stress? Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Adm. 2017, 3, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jalal, H. Determinants of Job Satisfaction in Higher Education Sector: Empirical Insights from Malaysia. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 2016, 6, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Reuben, C. Demographic Factors and Job Satisfaction: A Case of Teachers in Public Primary Schools in Bomet County, Kenya. J. Educ. Pract. 2017, 7, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, F.M.; Akter, T. Impact of Demographic Factors on the Job Satisfaction: A Study of Private University Teachers in Bangladesh. SAMSMRITI–SAMS J. 2019, 12, 62–80. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiou, S.; Garametsi, V. Perceived leadership style and job satisfaction of teachers in public and private schools. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 15, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Mallammal, M. Job Satisfaction among the Employees of A Industrial unit. Asian J. Manag. 2018, 9, 1043–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simarmata, N.; Astiti, D.P.; Wulan Budisetyani, I.G.A.P. Kepuasan Kerja Dan Perilaku Kewargaan Organisasional Pada Karyawan. J. Spirits 2017, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.S.; Rafie, N.; Selo, S.A. Job Satisfaction Influence Job Performance Among Polytechnic Employees. Int. J. Mod. Trends Soc. Sci. 2020, 3, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kónya, T.; Matić, R.; Pavlović, S. The Influence of Demographics, Job Characteristics and Characteristics of Organizations on Employee Commitment. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2017, 13, 120–138. [Google Scholar]

- Haleem, F.; Jehangir, M.; Khalil-Ur-Rahman, M. Job satisfaction from leadership perspective. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2018, 12, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.; Zhang, M.; Shan, H.; Zhang, L.; Yue, Y. Job satisfaction and union participation in China. Empl. Relat. 2018, 40, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyono, A.A.; Radianto, D.O.; Elisabeth, D.R. Antecedents of Job Satisfaction of Production Employees: Leadership, Compensation and Organizational Culture. Int. J. Entrep. Bus. Dev. 2019, 3, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chan, S.C.H. Participative leadership and job satisfaction. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoboubi, N.; Choobineh, A.; Ghanavati, F.K.; Keshavarzi, S.; Hosseini, A.A. The Impact of Job Stress and Job Satisfaction on Workforce Productivity in an Iranian Petrochemical Industry. Saf. Health Work. 2017, 8, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Gordon, S.; Tang, C.H. Momentary well-being matters: Daily fluctuations in hotel employees’ turnover intention. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, P.H.; Hernández, A.; González-Romá, V. Antecedents and consequences of workplace mood variability over time: A weekly study over a three-month period. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 94, 160–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drydakis, N. Trans employees, transitioning, and job satisfaction. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 98, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, S.S.; Ishola, A. Perception of collective bargaining and satisfaction with collective bargaining on employees’ job performance. Corp. Ownersh. Control. 2017, 14, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeffane, R.; Bani Melhem, S.J. Trust, job satisfaction, perceived organizational performance and turnover intention: A public-private sector comparison in the United Arab Emirates. Empl. Relat. 2017, 39, 1148–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Seifert, R. Pay reductions and work attitudes: The moderating effect of employee involvement practices. Empl. Relat. 2017, 39, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulidiyah, N.N. The Influence of Organizational Culture and Job Stress on Employees Performance by Job Satisfaction as an Intervening Variable in PT Binor Karya Mandiri Paiton Probolinggo. Asia Proc. Soc. Sci. 2018, 2, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abuhashesh, M.; Al-Dmour, R.; Masa’deh, R. Factors that affect Employees Job Satisfaction and Performance to Increase Customers’ Satisfactions. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 2019, 23, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, N.; Puente, F.A.C. Public versus private job satisfaction. Is there a trade-off between wages and stability? Public Organ. Rev. 2021, 21, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakotić, D. Relationship between job satisfaction and organisational performance. Econ. Res. -Ekon. Istraživanja 2016, 29, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Haq, I.U.; Azeem, M.U. Perceived contract violation and job satisfaction: Buffering roles of emotion regulation skills and work-related self-efficacy. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2020, 28, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M. Understanding the Nuances of Employees’ Safety to Improve Job Satisfaction of Employees in Manufacturing Sector. J. Health Manag. 2019, 21, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rožman, M.; Treven, S.; Čančer, V. Motivation and Satisfaction of Employees in the Workplace. Bus. Syst. Res. J. 2017, 8, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.W.; Cho, Y.H. The Moderating Effect of Managerial Roles on Job Stress and Satisfaction by Employees’ Employment Type. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, B.; Akey-Torku, B. The Influence of Managerial Psychology on Job Satisfaction among Healthcare Employees in Ghana. Healthcare 2020, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Deery, S. Why do self-initiated expatriates quit their jobs: The role of job embeddedness and shocks in explaining turnover intentions. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Kim, S.; Jung, J. The effects of a Master’s Degree on wage and job satisfaction in massified higher education: The case of South Korea. High. Educ. Policy 2020, 33, 637–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskat, B.; Reitsamer, B. Quality of work life and Generation Y: How gender and organizational type moderate job satisfaction. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, N.W.; Briley, D.A.; Chopik, W.J.; Derringer, J. You have to follow through: Attaining behavioral change goals predicts volitional personality change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 117, 839–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.Y.; Kee, D.M.H.; Akshay, K.C.; Jain, A.; Pandey, R.; Singh, A.; Chua, C.R.; Chia, J.W.; Arenas, V.T.; Lopez, C.A.; et al. How does Job Satisfaction Affect the Job Performance of Employees? Asia Pac. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 3, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaju, M.; Durai, S. A study on the impact of Job Satisfaction on Job Performance of Employees working in Automobile Industry, Punjab, India. J. Manag. Res. 2017, 9, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Miah, M.M. The impact of employee job satisfaction toward organizational performance: A study of private sector employees in Kuching, East Malaysia. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2018, 8, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strenitzerová, M.; Achimský, K. Employee Satisfaction and Loyalty as a Part of Sustainable Human Resource Management in Postal Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, P.; Schmidt, J.; Bosco, F.; Uggerslev, K. The effects of personality on job satisfaction and life satisfaction: A meta-analytic investigation accounting for bandwidth–fidelity and commensurability. Hum. Relat. 2019, 72, 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K.Z.B.; Jasimuddin, S.M.; Kee, W.L. Organizational climate and job satisfaction: Do employees’ personalities matter? Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.W. Job Attitudes in Management: Perceived Deficiencies in Need Fulfillment as a Function of Job Level. J. Appl. Psychol. 1962, 46, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alromaihi, M.A.; Alshomaly, Z.A.; George, S. Job satisfaction and employee performance: A theoretical review of the relationship between the two variables. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Traymbak, S.; Kumar, P.; Jha, A. Moderating Role of Gender between Job Characteristics and Job Satisfaction: An Empirical Study of Software Industry Using Structural Equation Modeling. Int. J. Hum. Cap. Inf. Technol. Prof. 2017, 8, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaji, N.; Akpa, V.O.; Akinlabi, B.H. An Assessment of the Effect of Job Enrichment on Employee Commitment in Selected Private Universities in South-West Nigeria. Funai J. Account. Bus. Financ. 2017, 1, 262–271. [Google Scholar]

- Yainahu, H.; Damayanti, D.; Devi, D. Job Satisfaction of TPK Group Yogyakarta Employees: Organizational and Industrial Psychology Perspectives. GUIDENA J. Ilmu Pendidik. Psikol. Bimbing. Konseling 2019, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.S.M. Job Satisfaction of Bank Employees in Bangladesh: A Comparative Study Between Private and State Owned Banks. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. (IOSRJBM) 2019, 21, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, G.J. Analysis of the causes of changes in non-regular workers in 2019: Where did the 870,000 non-regular workers come from, a surge in 2019? Korean Econ. Forum 2020, 12, 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, C.H. The effect of job stresses on job satisfaction of voucher service providers—Stress Coping Adaptation model. J. Commun. Welf. 2018, 64, 81–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Qureshi, J.A.; Thebo, J.A.; Shaikh, G.M.; Brohi, N.A.; Qaiser, S.; Nankervis, A. The nexus of employee’s commitment, job satisfaction, and job performance: An analysis of FMCG industries of Pakistan. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2019, 6, 1654189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J. The effect of job autonomy, job feedback and job manualization on the job satisfaction of the non-regular employees in a public corporation. LHI J. 2018, 9, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Brayfield, A.H.; Rothe, H.F. An index of job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 1951, 35, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleque, A.; Choudhury, N. Job Facets and Overall Job Satisfaction of Industrial Managers. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 1984, 20, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, A.S.M. Job Satisfaction of Bank Employees in Bangladesh: A Comparative Study Between Private and State Owned Banks II. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. (IOSRJBM) 2020, 21, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ampofo, E.T.; Coetzer, A.; Poisat, P. Relationships between job embeddedness and employees’ life satisfaction. Empl. Rel. 2017, 39, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sugar Mills | Level of Worker | Total (N = 300) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foreman | Worker | ||

| Rajshahi Sugar Mills Ltd. | 20 | 40 | 60 |

| Khustia Sugar Mills Ltd. | 20 | 40 | 60 |

| Mobarakgonj Sugar Mills Ltd. | 20 | 40 | 60 |

| Carew & Co (Bd) Ltd. | 20 | 40 | 60 |

| Faridpur Sugar Mills Ltd. | 20 | 40 | 60 |

| Total | 100 | 200 | 300 |

| No. of Items | Statements of Job Satisfaction Items | Source Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 01. | My job is like a hobby to me | JSI |

| 02. | My job is usually interesting enough to keep me from getting bored | JSI |

| 03. | It seems that my friends are more interested in their jobs | JSI |

| 04. | I considered my job rather unpleasant | JSI |

| 05. | I enjoy my work more than my leisure time | JSI |

| 06. | I am often bored with my job | JSI |

| 07. | I feel fairly well satisfied with my present job | JSI |

| 08. | Most of the time I have to force myself to go to work | JSI |

| 09. | I am satisfied with my job for the time being | JSI |

| 10. | I feel that my job is no more interesting than others I could get | JSI |

| 11. | I definitely dislike my work | JSI |

| 12. | I feel that I am happier in my work than most other people | JSI |

| 13. | Most days I am enthusiastic about my work | JSI |

| 14. | Each day of work seems like it will never end | JSI |

| 15. | I like my job better than the average worker does | JSI |

| 16. | My job is pretty uninteresting | JSI |

| 17. | I find real enjoyment in my work | JSI |

| 18. | I am disappointed that I ever took this job | JSI |

| Job Satisfaction Items | Full Questions | Source Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Pay | Are you satisfied with the salary/wages that you draw from your present job? | QMSF |

| Promotion | Are you satisfied with the promotional opportunity at your present job? | QMSF |

| Job status | Are you satisfied with the job status at your present job? | QMSF |

| Job security | Are you satisfied with the job security at your present job? | QMSF |

| Working condition | Are you satisfied with the working condition of your present job? | QMSF |

| Behaviour of boss | Are you satisfied with the behavior of your present boss? | QMSF |

| Open communication | Are you satisfied with the opportunity for open communication with your present boss? | QMSF |

| Autonomy in work | Are you satisfied with the autonomy in work at your present job? | QMSF |

| Recognition for good work | Are you satisfied with the recognition that is given for good work at your present job? | QMSF |

| Participation in decision making | Are you satisfied with the opportunity of participation in decision making at your present job? | QMSF |

| Relation with colleagues | Are you satisfied with the relation with colleagues at your present job? | QMSF |

| Age | Up to 25 Years | 6% (18 Persons) | Length of Service | Up to 10 Years | 29% (87 Persons) |

| Up to 35 years | 16% (48 persons) | Up to 20 years | 10.67% (32 persons) | ||

| Up to 45 years | 18% (54 persons) | Up to 30 years | 20.33% (61 persons) | ||

| Up to 55 years | 26.33% (79 persons) | Up to 40 years | 36.67% (110 persons) | ||

| Up to 65 years | 33.67% (101 persons) | Up to 50 years | 3.33% (10 persons) | ||

| Total | 100% (300 persons) | MIN = 2 years, MAX = 42 years; Mean experience of foremen 35.21 years (SD = 4.65) and for the worker 15.64 years (SD = 10.86). | |||

| MIN = 18 years, MAX = 60 years; Average age for workers 39.06 years (SD = 10.01). Average age for foremen 56.56(SD = 1.696). | |||||

| Education | Literate | 8.33% (25 persons) | Marital Status | Married | 91.33% (274 persons) |

| Class 1–5 | 15% (45 persons) | Unmarried | 8.67% (26 persons) | ||

| Class 6–9 | 50.67% (152 persons) | Total | 100 % (300 persons) | ||

| S.S.C | 15.67% (47 persons) | Hundred percent (100%) foremen are married while 87% workers were married and 13% were unmarried. SD = 8.997/ foremen; SD = 8.989/workers | |||

| H.S.C | 6.67% (20 persons) | ||||

| Degree & above | 3.67% (11 persons) | ||||

| Total | 100% (300 persons) | ||||

| MIN = Liberate, MAX = degree; average educational level of workers 3.29, and foremen 2.68. SD = 1.062 foremen; SD = 1.081 workers. | |||||

| Groups | Number | Mean | S.D | S. Err. Mean | z | df. | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean diff. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low age High age | 153 | 67.31 | 9.38 | 0.759 | −2.008 | 298 | <0.05 | −2.073 |

| 143 | 69.38 | 8.46 | 0.698 | |||||

| Lower education Higher education | 222 | 68.52 | 8.82 | 0.592 | 0638 | 298 | N.S | 0.749 |

| 78 | 67.77 | 9.48 | 1.073 | |||||

| Low experience High experience | 154 | 67.68 | 9.18 | 0.740 | −1.271 | 298 | N.S | −1.318 |

| 146 | 69.00 | 8.76 | 0.725 | |||||

| Married Unmarried | 274 | 68.21 | 9.08 | 0.549 | −0.698 | 298 | N.S | −1.288 |

| 26 | 69.50 | 7.97 | 1.562 |

| Level of Employee | N | Mean | SD | z | df. | Sig. (2-Tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreman | 100 | 68.92 | 8.997 | 0.813 | 298 | N.S |

| Worker | 200 | 68.03 | 8.989 |

| Source of Variation | Sum of Squares | df. | Mean Square | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects (combined) | 1908.712 | 9 | 212.079 | 2.765 | <0.01 |

| Sugar mills | 1473.487 | 4 | 368.372 | 4.803 | <0.01 |

| Level of worker | 53.402 | 1 | 53.402 | 0.696 | N.S |

| 2-way interactions | 381.823 | 4 | 95.456 | 1.245 | N.S |

| Residual | 22,242.925 | 290 | 76.700 | ||

| Total | 24,151.637 | 299 |

| Sugar Mills | Level of Worker | Total (N = 300) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foreman | Worker | ||

| Rajshahi Sugar Mills Ltd. | 65.65 (20) | 66.40 (40) | 66.15 (60) |

| Khustia Sugar Mills Ltd. | 71.20 (20) | 69.93 (40) | 70.35 (60) |

| Mobarakgonj Sugar Mills Ltd. | 68.00 (20) | 64.05 (40) | 65.37 (60) |

| Carew & Co (Bd) Ltd. | 69.10 (20) | 71.83 (40) | 70.92 (60) |

| Faridpur Sugar Mills Ltd. | 70.65 (20) | 67.93 (40) | 68.83 (60) |

| Total | 68.92 (100) | 68.03 (200) | 68.32(300) |

| Specific Aspect of Job | Foreman (N = 100) | Worker (N = 200) | Chi-Square | df. | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||

| Pay | 30 (30%) | 70 (70%) | 32 (16%) | 168 (84%) | 7.97 | 1 | <0.01 |

| Promotion | 70 (70%) | 30 (30%) | 147 (73.50%) | 53 (26.50%) | 0.408 | 1 | N.S |

| Job status | 83 (83%) | 17 (17%) | 153 (76.50%) | 47 (23.50%) | 1.678 | 1 | N.S |

| Job security | 76 (76%) | 24 (24%) | 124 (62%) | 76 (38%) | 5.880 | 1 | <0.05 |

| Working condition | 71 (71%) | 29 (29%) | 149 (74.50%) | 51 (25.50%) | 0.418 | 1 | N.S |

| Behaviour of boss | 86 (86%) | 14 (14%) | 160 (80%) | 40 (20%) | 1.626 | 1 | N.S |

| Open communication | 81 (81%) | 19 (19%) | 158 (79%) | 42 (21%) | 0.165 | 1 | N.S |

| Autonomy in work | 80 (80%) | 20 (20%) | 141 (70.50%) | 59 (29.50%) | 3.102 | 1 | N.S |

| Recognition for good work | 38 (38%) | 62 (62%) | 92 (46%) | 108 (54%) | 1.738 | 1 | N.S |

| Participation in decision making | 56 (56%) | 44 (44%) | 111 (55.50%) | 89 (44.50%) | 0.007 | 1 | N.S |

| Relation with colleagues | 97 (97%) | 3 (3%) | 199 (99.5%) | 1 (0.50%) | 3.167 | 1 | N.S |

| Statements of Job Satisfaction Items | Workers | Foremen | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My job is like a hobby to me. | Mean | 61.54 | 67.48 | 0.831 | <0.05 |

| SD | 8.72 | 8.92 | |||

| My job is usually interesting enough to keep me from getting bored. | Mean | 68.25 | 70.64 | 0.824 | N.S |

| SD | 8.47 | 9.58 | |||

| It seems that my friends are more interested in their jobs. | Mean | 53.56 | 67.12 | 0.847 | N.S |

| SD | 8.18 | 9.24 | |||

| I considered my job rather unpleasant. | Mean | 55.71 | 56.12 | 0.877 | N.S |

| SD | 8.82 | 8.88 | |||

| I enjoy my work more than my leisure time. | Mean | 69.54 | 78.14 | 0.912 | <0.05 |

| SD | 9.24 | 10.87 | |||

| I am often bored with my job. | Mean | 72.25 | 70.15 | 0.884 | N.S |

| SD | 8.79 | 7.58 | |||

| I feel fairly well satisfied with my present job. | Mean | 65.22 | 70.14 | 0.914 | <0.01 |

| SD | 8.26 | 9.75 | |||

| Most of the time I have to force myself to go to work. | Mean | 78.81 | 67.85 | 1.250 | <0.05 |

| SD | 9.78 | 8.44 | |||

| I am satisfied with my job for the time being. | Mean | 67.11 | 69.33 | 0.874 | N.S |

| SD | 7.66 | 8.02 | |||

| I feel that my job is no more interesting than others I could get. | Mean | 59.49 | 63.65 | 0.911 | N.S |

| SD | 7.88 | 8.01 | |||

| I definitely dislike my work. | Mean | 70.54 | 52.88 | 1.402 | <0.01 |

| SD | 9.85 | 7.54 | |||

| I feel that I am happier in my work than most other people. | Mean | 68.25 | 69.45 | 0.811 | N.S |

| SD | 8.12 | 8.74 | |||

| Most days I am enthusiastic about my work. | Mean | 61.78 | 69.48 | 0.845 | <0.05 |

| SD | 8.02 | 8.97 | |||

| Each day of work seems like it will never end. | Mean | 71.21 | 62.01 | 1.348 | <0.01 |

| SD | 9.78 | 8.44 | |||

| I like my job better than the average worker does. | Mean | 67.52 | 69.70 | 1.240 | N.S |

| SD | 8.55 | 8.96 | |||

| My job is pretty uninteresting. | Mean | 68.14 | 68.66 | 0.821 | N.S |

| SD | 8.11 | 8.23 | |||

| I find real enjoyment in my work. | Mean | 67.54 | 70.35 | 0.954 | <0.05 |

| SD | 8.91 | 9.79 | |||

| I am disappointed that I ever took this job. | Mean | 70.56 | 67.85 | 1.865 | <0.01 |

| SD | 9.14 | 8.45 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Issa Gazi, M.A.; Islam, M.A.; Sobhani, F.A.; Dhar, B.K. Does Job Satisfaction Differ at Different Levels of Employees? Measurement of Job Satisfaction among the Levels of Sugar Industrial Employees. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063564

Issa Gazi MA, Islam MA, Sobhani FA, Dhar BK. Does Job Satisfaction Differ at Different Levels of Employees? Measurement of Job Satisfaction among the Levels of Sugar Industrial Employees. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063564

Chicago/Turabian StyleIssa Gazi, Md. Abu, Md. Aminul Islam, Farid Ahammad Sobhani, and Bablu Kumar Dhar. 2022. "Does Job Satisfaction Differ at Different Levels of Employees? Measurement of Job Satisfaction among the Levels of Sugar Industrial Employees" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063564

APA StyleIssa Gazi, M. A., Islam, M. A., Sobhani, F. A., & Dhar, B. K. (2022). Does Job Satisfaction Differ at Different Levels of Employees? Measurement of Job Satisfaction among the Levels of Sugar Industrial Employees. Sustainability, 14(6), 3564. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063564