1. Introduction

Over the last 30 years, several European states have collapsed: the USSR, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia. It seems to be a good time now to find out how regional development is formed on the newly created border, which has suddenly become a harder or softer barrier, with the territory close to it becoming a periphery.

Our attention is focused on the Czech–Slovak border, where the development was relatively calm and which after a certain time became the internal border between EU states. Nevertheless, we believe that the question of the impact of the restoration of the state border here plays a role, even though the border is freely passable for people and goods and the language barrier is negligible. Legislative systems, social security systems and, finally, monetary systems have been separated. Relations with Slovakia have formally reached the level of relations with other EU states.

Of course, the situation is complicated. Other factors that are only marginally or not at all related to the new border can also play a role. For example, Eastern Moravia has become the most remote part of the Czech Republic in terms of the West–East gradient. Toušek and Tonev [

1] showed that the interest of foreign capital in supporting the economy in districts in the Czech–Slovak borderland was by far the lowest in comparison with the borderland with all other neighbors, before joining the European Union. The structural reconstruction of the economy in market conditions certainly has its specifics. Everything takes place against the background of general trends in the transition to a post-industrial society, globalization, climate change and other current processes.

In our study, we raise the question of whether rural peripheral micro-regions (the term microregion is used in our work to distinguish it from administrative regions (NUTS 3); micro-regions, on the other hand, are real functional regions integrated in particular by commuting to work and services) on the eastern border of the Czech Republic show increased peripheralization after the division of Czechoslovakia and whether there are conditions and ideas to overcome them. The importance of this contribution lies in the fact that it draws attention to the border regions at the new state borders, which are dealing with the problem of division. Such studies dealing with the new borders between Russia and the former federal republics of the USSR or between the states of the former Yugoslavia are either missing or not part of the international literature. Moreover, in our case, there were multiple changes in the geopolitical situation over a relatively short period.

2. Theoretical Background

The key theoretical question is how to understand the concept of regional development and how it can be evaluated. Some authors identify development with quantitative growth [

2]. This approach corresponds to the productive (modern, Fordist) period, and today it is more typical for developing countries [

3], or for some post-Soviet approaches, which put economic factors of development in the forefront [

4]. At the same time, Farooq and Ahmad [

5] admitted that economic growth does not necessarily mean reducing poverty. Leick and Lang [

6] argued that times of permanent growth of economy and population have come to an end for many European regions. It shows that it is necessary to change planning approaches for regions beyond growth.

Michalska-Żyła and Marks-Krzyszkowska [

7] assumed that economic development and the development of quality of life cannot be equated. The policy of the European Union—although formally forcing multifunctional rural development—is focused primarily on the support of agriculture and tourism [

8], which more or less corresponds to the traditional focus. It is to be feared that the more modern conception is hindered mainly by the lobbyist interests of agricultural entrepreneurs. Hrabák and Konečný [

9] emphasize the importance of multifunctional agriculture for rural development, especially in mountain areas, which do not have favorable conditions for the development of traditional intensive agriculture.

In connection with the transition to a post-productive society, consumption in the broadest sense, i.e., the consumption of tangible and intangible values [

10], including landscapes [

11], buildings, traditions and habits, come to the fore. The quality of life or well-being of villagers (including entrepreneurs and visitors) is not determined by economic factors only [

12]. Factors, such as access to education and medical care, personal safety, social inclusion, and participation in community life, but also subjective factors, such as satisfaction and happiness, come into play. The problem is that these factors are very difficult to identify and evaluate. However, if we are talking about regional development in rural areas, we need to focus on this direction because the possibilities of quantitative development encounter demographic, environmental and economic barriers. Many authors consider the quality of social capital to be a key factor in rural development at the local level [

13].

Areas that are becoming borders can also become a periphery [

14]. Peripheral regions are often characterized by depopulation, unemployment, lagging infrastructure, lack of investment and, ultimately, a deterioration in the quality of life of the local population. The border position may also mean the advantage of cooperation with the partner country, or even with a share of the grey economy [

15]. Kühn [

16] states that peripheralization is not just a function of distance, but that it is a multidimensional concept involving economic polarization, social inequality and the division of power. An important question is also related to the mental periphery, i.e., whether the inhabitants of remote regions perceive their location as peripheral and how the people from central regions perceive the periphery [

17].

Depopulation is initially the result of a negative migration balance. Whereas young and educated people, in particular, are looking for a career in more developed areas and more attractive sectors, seniors remain in peripheral regions. This leads to secondary depopulation due to natural population decline [

18]. This trend should not become irreversible and no longer solvable by regional policy instruments [

19].

The approach and significance of border research have changed dramatically in the last decades [

20]. The first expert analyses concerning state borders dealt with the delimitation of borders based on natural, historical, traffic, ethnic, religious and other characteristics of the territory. Their practical significance most often lay in the justification or rejection of territorial claims between neighboring states. State borders were usually more of a formal line for local people until the emergence of nation states, which began to defend national markets in the form of tariffs and other barriers. Often, state borders became a hard barrier and borders between enemy states on which fortifications and other military establishments were built. The extreme form was an iron curtain, or defended fences and walls, preventing the passage of people. Many changes took place in Central Europe, from the disintegration of Austria–Hungary through the disintegration of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia to the division and reunification of Germany [

21]. Kolosov and Więckowski [

22] pointed out several changes not only in the state borders, but also in their character, especially in Central and Eastern Europe in the 20th century.

Concerning the fall of the Iron Curtain, the interest of Czech geographers in border research has intensified. However, the greatest attention was paid to the border, which was occupied by the German Empire after the Munich Agreement and was where several problems accumulated. The expulsion of the majority of the German population after the Second World War and its replacement by Slavic immigrants is significant, which meant the interruption of centuries of development of localities and the arrival of inhabitants who had no previous experience with this type of territory [

23]. Another problem is the sharp post-war decline in population, which, together with military measures at the state border, led to the demise of plenty of settlements. Other borders (except Slovakia) are also within easy reach of Prague and regional capitals, which has led to a significant increase in second homes. In contrast, the Czech–Slovak border was considered relatively problem free, was not burdened by ethnic conflicts, and had a more stable population for a long time. Perhaps that is why special attention was not given to this section of the borderland.

After experiencing two world wars, the western part of Europe concluded that it was necessary to change the nature of relations between states and, subsequently, change the state borders from lines of confrontation to areas of cooperation. These ideas were expressed in the creation of the European Union and later in the creation of the Schengen area, which allows the free movement of people and goods. The importance of research into state borders and border areas in Europe has increased since the fall of the Iron Curtain [

24].

However, free movement is not enough. It is necessary to actively remove the burden of the past and to develop various forms of cooperation. That is why a system of Euroregions was created [

25]. Euroregions are the EU’s instrument for cross-border cooperation. Their purpose is, in fact, to overcome mistrust among the inhabitants of border regions and to build cultural and social bridges, creating a cross-border social capital [

26]. The effectiveness of cross-border cooperation through Euroregions varies. In principle, the decisive factors are, inter alia, the different degrees of centralization in neighboring states, i.e., how far municipalities and other entities directly on the border are legally subjective to institutionalize cooperation. Equally important are motivations for cross-border co-workers. In some cases, it is simply a matter of overcoming the psychological barriers that were created in the past. The cooperation is directed from the cultural level—creating sub-state diplomacy [

27], and in others, it may be the cooperation of a more complex level, including economic life [

28]. The economic strength of neighboring regions is probably also important—whether these are economically developed or marginal regions, or how large the economic differences are between them. Medeiros [

29] points out that EU cross-border cooperation programs are often used to finance the development of national border areas rather than to overcome cross-border barriers. However, the case of the Czech–Slovak border is different because it was a matter of dividing the state and thus maintaining an atmosphere of trust and cooperation.

Jeřábek et al. [

30] distinguished three stages of cross-border cooperation of Czechoslovak and later Czech and Slovak regions: (a) the period 1989–1992, which is characterized by the so-called “wild” (spontaneous) cooperation without much coordination, mostly at the municipal level, (b) the period 1993–1996, when the European Union enters this cooperation, which sees (border) regions as the engine of cross-border cooperation (so-called Euroregions are created along the borders), and (c) the period after 1997, when this regional institutional cross-border cooperation coordinated by the European Union takes concrete form and when cooperation takes place with local institutions. Cross-border cooperation in the Moravian–Slovak borderland was supported by the European Union even before the accession of both countries to the EU [

31]. At present, the Moravian–Slovak border is covered by the Euroregions Beskydy/Beskidy (with Poland as the third partner) in the northern part [

32] and Bílé Karpaty/Biele Karpaty in the southern part of the borderland. The question of overcoming the psychological barriers of extraordinary hostility is out of the question in the case of Czech–Slovak relations. The regions on both sides are also ethnically and linguistically close because the ethnographic transition between Slovakia and Moravia is not sharp, but gradual.

There is not much work comparing rural development on the Moravian–Slovak border. Smékalová et al. [

33] compared the effectiveness of the use of structural funds in the Zlín and Trenčín regions with ambiguous results. The regions on the Slovak side are among the most advanced in Slovakia in terms of GDP per capita. However, this does not have much effect on the development of cross-border cooperation. If there is cross-border commuting from Slovakia, it goes more to Austria [

34].

The key question is what cooperation should border regions that are not relatively economically advanced be based on. One of the possibilities is the joint protection of nature and natural values. The second option is the development of cross-border tourism. On the other hand, economic cooperation and cross-border commuting to work are almost out of the question.

Of course, the changes in society as a whole cannot be neglected either. In connection with the transition to a post-industrial society, the European countryside is changing from an area for agricultural production to a multifunctional landscape [

35,

36]. Murdoch and Pratt [

37] even discussed post-rural areas, whereas Oliva and Camarero [

38] used the terms de-peasantization and de-agrarianization. These changes are accompanied by a shift in labor from the manufacturing sector to services. It is the speed of this process that can be a measure of the achieved level of regional development. At the same time, it seems clear that large cities are characterized by the fastest growth in the services sector, while the countryside is lagging. The reason is obvious. Most services tend to be concentrated, and therefore located in the centers of each hierarchical level. One of the services that partially deviates from this rule is tourism services that are tied to deconcentrated attractions—natural beauty or cultural heritage. This is important, especially in lagging areas [

39].

The role of the development of cultural tourism in the post-industrial countryside is emphasized, for example, by Vidickiene, Vilke and Gedminaite-Raudone [

40], who discussed transformative tourism. The development of cultural tourism in rural areas is made possible, inter alia, by the development of tourism from an elite sector to a sector for the general masses of Europe [

41]. Băndoi et al. [

42] pointed to the positive relationship between the development of tourism and the quality of life of local people—although this relationship may also be contradictory, especially in the case of over tourism.

The question remains of what forms of tourism are possible for remote rural micro-regions. By far, the most frequent is second housing in cottages and chalets. This form does not bring much financial benefit to rural regions, but has saved many rural buildings and, through contacts between cottagers and locals, enables contacts between urban and rural lifestyles and supports regional identity [

43]. From a different perspective, it can also be preparation for permanent housing. In addition, the rental of individual cottages is developing today. Other possible forms of tourism in these areas are outdoor recreation (summer by the water and winter in mountains), ecotourism, nostalgic tourism and sightseeing cultural tourism. These forms of tourism do not bring much financial benefit—unless they are of a mass nature. However, building mass tourism is not in line with the quality of life of the locals. Efforts to build capacity for more affluent clients have not been met with success [

44]. Agritourism is not yet very developed in Czech remote rural areas [

45].

The paper then focuses on the evaluation of the possibilities of development in rural areas of Eastern Moravia in the near future. The main research question is the possibility of developing regions that have become remote as a result of the changing geopolitical situation.

3. Methods

The historical–geographical method and the path-dependency method were used to understand the current state of the studied region. This method is based on the experience that past developments affect the current situation [

46]. It can be about using past experience or avoiding past mistakes.

The basic methodological problem is to find indicators and criteria for evaluating rural development in terms of the quality of life of its inhabitants. Of course, sociological methods of a questionnaire survey, guided interviews and other procedures are offered. These methods—if they are to be sufficiently meaningful—require complex preparation, ensuring representativeness, careful implementation and evaluation [

47]. Ultimately, they are costly and time consuming.

Another possibility is to use a set of variously selected economic, social, demographic, environmental and political indicators with a greater or lesser relationship to quality of life. Kebza [

48], in analyzing the degree of peripherality, used six indicators: unemployment rate, net migration rate, age dependency index, gross leasable area, number of students and number of occupied job opportunities. The main problem is to find the weights of individual indicators in the whole system and sometimes to determine the relationship of individual indicators to quality of life. The question of the subject’s quality of life also arises here, as seniors will probably have different preferences from juniors and employees will have different preferences from entrepreneurs. Therefore, this approach is more suitable for the evaluation of individual aspects of quality of life and for smaller areas where field experience can be applied.

Would it be possible to find any publicly available and frequently updated statistical indicators that would indicate the objective and subjective aspects of the qualitative aspects of rural development? We believe that the migration balance speaks very comprehensively about the quality of life. We assume that contemporary people in Europe are moving from places with a lower quality of life to places with a higher quality of life—no matter how individuals define the quality of life. Hoogerbrugge and Burger [

49] admitted that at least part of selective migration can be explained by differences in life satisfaction—especially on the side of urban–rural migration. Of course, it can be argued that some people cannot move out of low-quality-of-life areas for financial or other reasons. Therefore, it seems appropriate to supplement this indicator with the number of newly built dwellings. Although in this case, other factors, especially the price and availability of building plots, may play a role, we do not assume that anyone would build an apartment in an area they do not like.

The migration balance (the number of immigrants to individual settlements in the area minus the number of emigrants from them) and completed dwellings is calculated for the five years of 2016–2020. The studied area is monitored according to the catchment areas of authorized municipal authorities to capture even smaller intra-regional differences. Another additional indicator is the level of unemployment (number of available job seekers to the number of inhabitants aged 15–64), which may be one of the motives for migration—even though this indicator is losing its significance compared to the past, due to an increasing proportion of the population being pensioners. In Czech conditions, unemployment is not a general problem, but its locally increased level may signal local disparities in the labor market. As an additional indicator, the age structure of migrants was analyzed according to their age groups and the main directions of migration from the region of interest.

4. Study Area

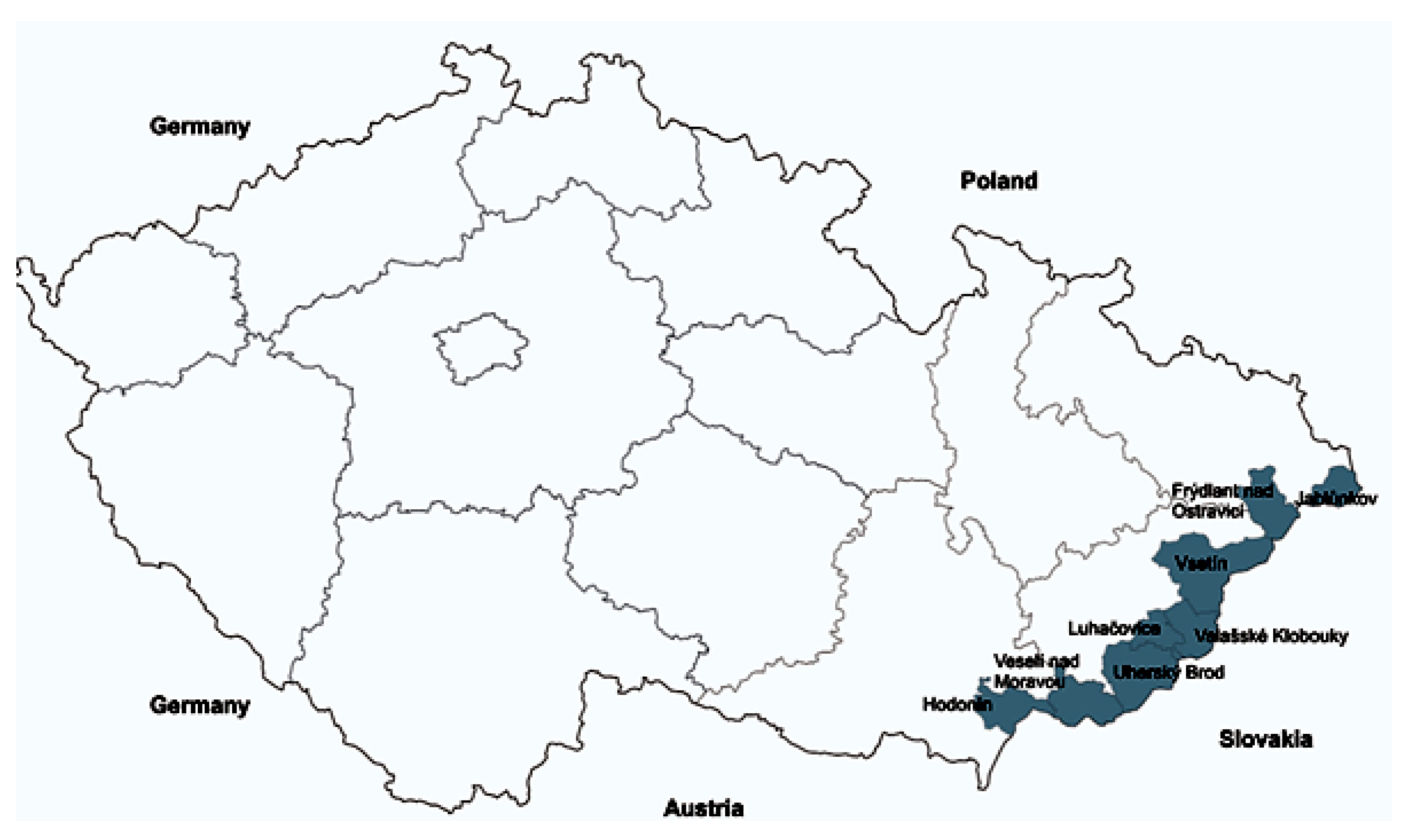

The studied area (

Figure 1) was delimited by catchment areas of municipalities with extended powers on the border with the Slovak Republic. (It is an intermediate stage between municipalities (LAU 2) and districts (LAU 1). Municipalities with extended powers (usually small- or medium-sized cities) carry out some professional agendas for municipalities in their background, which are not effective or possible to perform in too-small municipalities. However, municipalities with extended powers are not superior to municipalities in their catchment area. In some cases, there is another intermediate stage—municipalities with an authorized municipal office, if the catchment areas of municipalities with extended powers are too large and it is expedient to carry out some agendas closer to the population.) These municipalities are located in three NUTS 3 regions: South Moravian (Hodonín and Veselí nad Moravou), Zlín (Uherský Brod, Luhačovice, Valašské Klobouky, Vsetín, Rožnov pod Radhoštěm) and Moravian-Silesian (Frýdlant nad Ostravicí, Jablunkov (the catchment area of Frýdek-Místek, which extends only marginally to the border, was omitted because its center has more than 50,000 inhabitants and a population density that reaches 232 people per km

2; for this reason, it can be hardly included among the peripheral rural regions)). Against them, there are nine administrative districts of three regions on the Slovak side: Žilina, Trenčín and Trnava. The area under study is mostly covered by the mountain ranges of the White Carpathians and Moravian-Silesian Beskid Mountains and their foothills and side valleys. The only exception is the microregion of Hodonín, which already falls into the Lower Moravian lowland and wine-growing area. The rest of the area is destined for extensive organic farming, which, however, creates its high dependence on subsidies. The total area is 2934 km

2. In the Slovak part, the territory borders with Kysucké Beskydy Mts., Javorníky (Maple Mts.), White Carpathian Mts. and Záhorie lowland.

The area was covered mainly by forests (46.8%) at the end of 2019. Arable land accounted for 21.4%, permanent grassland 18.3%. Other types of land use were insignificant: permanent crops (vineyards, gardens, orchards 3.4%, water areas 1.4%, and built-up areas 1.5%). At the end of 2020, almost 340,000 inhabitants lived in the studied area, which, due to the mountainous nature of the relief, represents an unexpectedly high density of 116 inhabitants/km2. There are a total of 169 municipalities in the area, of which only 8 have less than 200 inhabitants. There are 72 large rural municipalities with more than a thousand inhabitants and 48 medium-sized rural municipalities with 500 to 999 inhabitants. There are 13 towns with more than 5 thousand inhabitants, of which over 20 thousand have Vsetín (26 thousand) and Hodonín (24 thousand). This structure is also non-standard in the Czech conditions, where very small and small rural municipalities predominate. Not all municipalities are compact villages. In some places, there is a scattered settlement.

The population of the studied area is 45.4% employed in manufacturing industries (agriculture, forestry, fishery, manufacturing and building industry). (The data are from the 2011 census, as data from the 2021 census have not yet been published. It can be assumed that the ratios are maintained, although the shares of employees in the manufacturing sectors are generally declining). This is 10.5 percentage points more than the national average (see

Table 1). From this point of view, Eastern Moravia is a significantly rural and lagging-behind area. This corresponds to the share of people over the age of 15 with a high school diploma, which reaches 39.2%, which is 4.4 percentage points less than the national average. Only the districts of Luhačovice (with a spa function) and Frýdlant nad Ostravicí (the goal of suburbanization of Ostrava and its agglomeration) have industrial employment at the national average.

At the end of 2020, the population age index (the share of the number of seniors over the age of 50 and children aged 0–14) in Eastern Moravia was 1.35 in comparison with the national value of 1.26. The population of the monitored region is, therefore, relatively older (see

Table 1). The oldest population has the district of Veselí nad Moravou in the southern part of the border, while the northernmost district of Jablunkov has a population relatively young, even compared to the national average.

According to the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs of the Czech Republic, unemployment in the region was 3.6% in December 2021, while national unemployment was 3.5% (see

Table 1). At present, the problem is the availability of a skilled workforce to maintain production. Increased unemployment can be found in both of the southernmost micro-regions, while in the middle of eastern Moravia, the value of this indicator is around 2%, which signals a shortage of the labor force. On the Slovak side, unemployment is similar to the top in the northern section of the borderland, as the districts of Western Slovakia have the lowest level of unemployment in the country: Trnava region 4.2%, Trenčín region 4.3%, and Žilina region 5.3%.

The area includes several specific ethnographic areas with a distinctive culture. From the south, these are Horňácko (as part of Moravian Slovakia), Wallachia, Lachia and Těšín Silesia (in the last two, elements of Polish culture can also be found). This, on the other hand, may signal a certain conservatism of the local population. The area has many attractions for the development of cultural tourism. Natural values are protected within the protected landscape areas of the White Carpathians and the Beskid Mountains, which have their counterparts in protected landscape areas Biele Karpaty and Kysuce in Slovakia and occupy a significant part of the territory. Conditions allow summer and winter tourism. In the territory of Eastern Moravia, there are also many monuments of archaeological nature, medieval fortifications, church and secular buildings, important open-air museums in Rožnov pod Radhoštěm and Strážnice, work and native places of important personalities, such as J.A. Komenský, L. Janáček and others, as well as modern attractions. The local, partly lively folklore, manifested in folk art, customs and traditions, is unique. The most important Moravian spa Luhačovice (

Figure 2) is also located here.

There are 498 collective accommodation facilities in the region (2020), which have 9216 rooms with 27,219 beds. This represents 9.3 beds per km

2. This value slightly exceeds the national average, which is 7.5 beds per km

2. In the last pre-COVID year 2019, 2,315,761 overnight stays were recorded, of which 35.6% were in the Luhačovice area. It represents 6.8 overnight stays per inhabitant (to compare with the national average of 5.3 overnight stays per inhabitant). Of the total overnight stays, 10.8% were foreigners (in the national average it was 47.7%), so the region is oriented to domestic tourism. To the accommodation capacity, it is necessary to add 4524 unoccupied flats used for recreation (2011). In addition, Kubeš [

50] estimates the number of holiday cottages in the Beskydy region at 11,200. This can mean around 60,000 beds—double the number of beds in collective facilities. However, these beds are mostly used only for individual recreation of the owners and their friends.

5. Short Historical Overview

There is an opinion that the Czech–Slovak border is a new one. However, this only applies in the short term. In fact, both sides of the border were part of one state unit during the Great Moravia (The exact name of the then state is not known. The term Great Moravia is of a later date and serves primarily to separate today’s Moravia from the then empire, which occupied a relatively large part of Central Europe, including Bohemia, Lusatia, Silesia, Pannonia and other territories. There are also uncertainties about the territorial area and centers of Great Moravia [

51].), which originated from the connection of Moravian and Nitra principalities in 833 and ended probably by the refutation by Avars in 907. After that, the border was the division between the Moravian Margraviate/Czech Kingdom and Hungary for 1011 years. Although for some period the Czech lands and Hungary were personally united by the same ruler, the border has always existed here.

It should be noted that, except for the southernmost part, it was a very sparsely populated and late colonized area. Wallachian colonization did not come here until the 16th and 17th centuries. The population subsisted on pastoralism. Family breadwinners often went throughout the monarchy and beyond during the summer seasons. Many people also emigrated overseas.

Pastoralism has led to extensive deforestation. The situation changed during industrialization, which released the pressure on the landscape. Changes in agriculture in the second half of the 20th century—collectivization (the 1950s), mechanization (1960s), industrialization (1970s) and intensification (1980s) resulted in an increase in arable land in the foothills and mountain areas [

52]. In addition to compact villages, the settlement also contains small settlements or solitudes. The northern part of the borderland has been under the influence of the Ostrava Industrial Agglomeration since the 19th century, based on hard coal mining and heavy industry.

The Czechoslovak period, although relatively short, brought very significant changes to the territory of Eastern Moravia. The shoe company Baťa was developed in Zlín. It was a complex company, which operated not only in footwear, but in many other industries (manufacture of tires, technical rubber, man-made fibers, toys, metalworking machines, knitting machines, aircraft, and bicycles). The group employed 67,000 people. The company introduced a special motivation system [

53]. To transport coal from the South Moravian lignite district, a canal was built. Branch factories were built in borderland small towns. This way of conducting business significantly affected the entire business environment of the Zlín and Vsetín areas.

Another impetus for the industrialization of the region was the approaching second world war, which evoked a boom of the Czechoslovak armament industry [

54]. The Czech lands were surrounded by Hitler’s Germany on three sides. All large Czech armories were directly threatened by bombing by German planes taking off from Austria and landing in Silesia (or vice versa). Therefore, each Czech armory built one or two daughter armories in mountain valleys in Eastern Moravia or Western Slovakia, where these factories were more sheltered from enemy air raids, and where the Czechoslovak army would withdraw from enemy attacks. The result was a series of armaments and ammunition companies in Uherský Brod, Bojkovice, Slavičín, Vsetín, and Kunovice. These companies have significantly contributed to the industrialization of the former agricultural and forestry areas.

The connection of Czechia and Slovakia required the construction of large-capacity communications in the west–east direction. Originally, the only long-distance connection between Czechia and Eastern Slovakia was the Košice-Bohumín Railway. Additional railways were put into operation through the Lyska and Vlára passes. More road connections have been built.

The flat and more accessible southern part of the Moravian-Slovak border (the Hodonín area) was surprisingly industrialized later; perhaps because it provided favorable conditions for intensive agriculture and viticulture. The sugar industry was the first leading branch here. In the 1950s, a power plant processing local lignite and a modern sugar factory was added to the 19th-century tobacco factory. Quality oil is mined in the area.

In any case, at the end of the Czechoslovak period, East Moravia, formerly a pastoralist and handicraft region, was an industrialized area, including the relevant consequences for the qualification structure of the population, the infrastructure and the like.

The demise of Czechoslovakia in 1993 changed the geopolitical position of the region. From the area in the middle of the state, it became a peripheral territory—moreover, on the least attractive eastern edge. Complications began to manifest gradually. The state border remained freely permeable for citizens of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic, but not for citizens of third countries. This limited tourism because foreign tourists could not use hiking and skiing trails passing from one state to another. Another problem was the separation of currencies. Social security systems (pensions) have also been separated, so it has become disadvantageous for the citizens of Czechia to work in Slovakia. It is obvious that the intensity of cross-border traffic has decreased significantly [

55] as well as cross-border commuting [

56].

The current integration of Czechia and Slovakia first into the European Union in 2004 and later into the Schengen area from its inception in 2007 brought new impetus. Theoretically, the state border should change in the line of cooperation; however, some barriers remain at the local level. This is both a natural barrier (mountains and a watercourse) and a psychological barrier [

57], which in this case is less significant.

6. Results

Between 2016 and 2020, 19,792 people immigrated to the region, while 21,217 inhabitants emigrated (

Table 2). All districts recorded a negative migration balance, except for Frýdlant nad Ostravicí, which is highly positive (+30.5‰). The Frýdlant region lies in the hinterland of the Ostrava industrial agglomeration and is therefore the subject of the remote suburbanization of Ostrava. On the other hand, the districts of Luhačovice (−12.3‰), Valašské Klobouky (−11.6‰) and Veselí nad Moravou (−11.0‰) have a relatively high negative balance of migration. These are districts of smaller centers. The micro-regions of the large centers of Vsetín, Hodonín, Uherský Brod and Rožnov pod Radhoštěm have high absolute population declines (over 500 persons), but the emigration shares are relatively lower.

The position of the largest towns in the region is interesting. All four with a population over 15,000 (Hodonín, Vsetín, Rožnov pod Radhoštěm and Uherský Brod) are significantly passive in terms of migration. They always account for the majority of the negative migration balance of their micro-regions. It can be said that without these cities, the migration balance of their micro-regions would be almost balanced. It is also possible that many people are moving from these centers to the villages around them, and therefore it is a kind of micro-suburbanization.

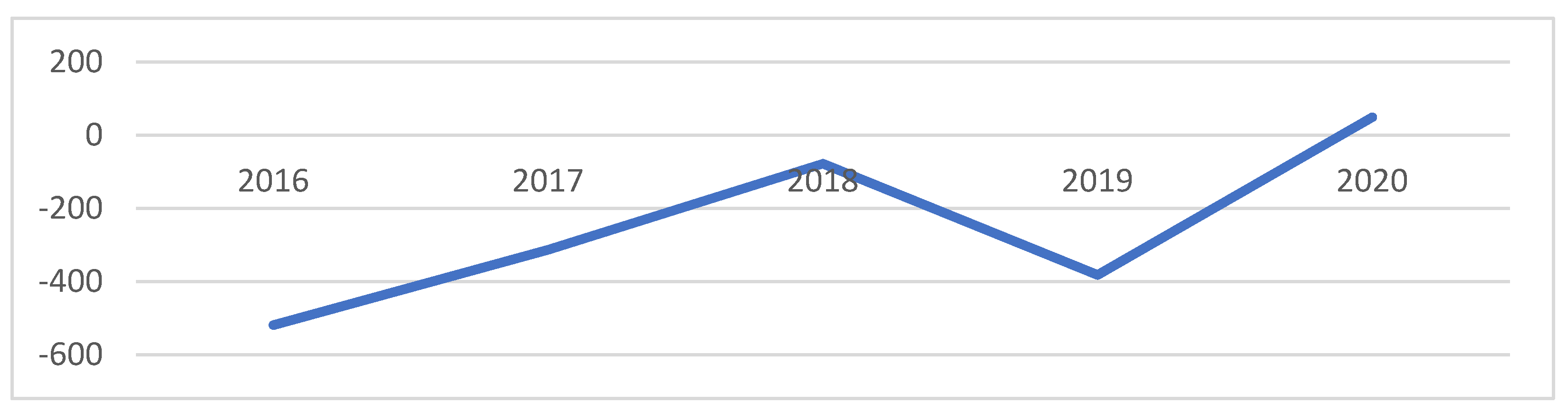

An interesting fact is that the negative migration balances had a decreasing tendency during the monitored five years (

Figure 3). In 2020, the region as a whole recorded even a very slight migration increase. This is to some extent in line with the reversing trend from rural-to-urban to urban-to-rural migration.

Of the total number of 3025 emigrants outside the studied region in 2020, people in the age group 0–14 years made up 22.6%, people in the productive age group 15–64 years 71.7% and seniors aged 65 and over only 5.7%. The age structure of immigrants is similar. Of the 2787 immigrants, 24.8% were children and young people, 69.1% were people of working age and 6.1% were seniors. Therefore, it is not obvious that young people are moving out and being replaced by seniors.

Of the total number of emigrants, 11.7% went to Prague and 9.4% to Brno. Ostrava is more important for the Frýdlant nad Ostravicí microregion. Significant migratory flows are directed to nearby medium-sized cities. For the southern part of Eastern Moravia, a center is Uherské Hradiště, for the central part, Valašské Meziříčí and, to a limited extent, Zlín, and for the northern part, Frýdek-Místek and Třinec. Certain numbers are directed to neighboring micro-regions and the rest is dispersed. Immigration flows are the strongest from Ostrava and its agglomeration to the micro-regions of Frýdlant nad Ostravicí and partly Jablunkov.

As a result, current migration is in line with traditional patterns. While the migration of seniors is minimal, mainly people in the first half of the productive age with children migrate. In addition, only about a quarter of emigrants go to the big cities. The rest are looking for employment in nearby medium-sized cities, corresponding to their qualification structure. It may indicate that they do not intend to sever ties with their original residence.

New apartments are appearing more in the northern part of the territory. Surprisingly, however, relatively, most of the new dwellings per 1000 inhabitants were built not in the Frýdlant district, but the Rožnov pod Radhoštěm district, followed by Frýdlant nad Ostravicí (

Figure 4) and Jabunkov. This means that high immigration into the Frýdlant microregion is not accompanied by adequate housing construction. Immigrants, therefore, partly use the existing housing stock. On the contrary, the lowest numbers of new dwellings per thousand inhabitants are in the southern districts of Hodonín, Veselí nad Moravou and Luhačovice.

The level of unemployment in June 2021 fell below 3% in the micro-regions Uherský Brod, Luhačovice, Valašské Klobouky Rožnov pod Radhoštěm and Jablunkov, i.e., mainly in the central and northern parts of the Moravian-Slovak borderland. The highest unemployment can be found in the southern micro-regions of Hodonín and Veselí nad Moravou.

7. Discussion

Data on migration as well as data on newly built dwellings are published annually by the Czech Statistical Office at the municipal level. This means that the analysis can be performed and repeated for any territory composed of municipalities, annually and without additional financial costs.

In terms of practical use, there is one significant objection to the methodology used. There is a relatively long delay between a change in the quality of life and a migration decision. Therefore, the methodology reflects rather the past characteristics of the region. Although it can be assumed that quality of life does not change too quickly regionally, in the event of significant changes in the geopolitical, economic or other situation, other indicators must also be used. However, the proposed indicator enables long-term monitoring of trends after individual years, so it is possible to respond to emerging problems relatively quickly. The second objection is that the proposed methodology does not address the differentiated values and demands of different demographic, cultural and social groups of the population. While mostly career-oriented people leave peripheral rural regions (permanently or temporarily), environmentally oriented people can stay or immigrate.

The uniqueness of the Frýdlant nad Ostravicí district shows that the quality-of-life evaluation based on migration cannot be assessed absolutely but always as differences between the sources and targets of migration. The differences between the comprehensively understood quality of life in Ostrava (respectively its image) and the Frýdlant nad Ostravicí district are so significant that they cause relatively intense migratory movements. Other parts of Eastern Moravia do not have such counterparts.

Although there are plenty of job opportunities in the industry, except for the southernmost part of the study area (the region even seems to be facing labor shortages), structural restructuring is inevitable. The high share of industry is no longer a sign of progressiveness, but rather of backwardness. Job opportunities in the industry will decline in the long run due to changes in labor productivity and the overall post-productive transformation. The transfer of a significant part of the workforce from industry to services is also important for cultivating the human factor within the post-productive economy.

A certain positive signal is a fact that the perception of Eastern Moravia is not explicitly peripheral. From the center’s point of view, the border periphery from which the German population was evicted after World War II is far stronger and therefore has to deal with the consequences of ethnically conditioned population exchange, disruption of historical continuity and difficult relationship-building. East Moravia does not have these problems. From the point of view of its inhabitants, these are traditional ethnographic regions connected by a distinctive culture and a high degree of regional identity.

To evaluate the overall situation, we summarized the strengths and weaknesses of the region, its opportunities and threats (

Table 3).

While the first structural change from a pastoral and forestry area to a manufacturing region was the result of a change from a pre-productive to a productive society, the forthcoming change from a production region to a consumer region is a consequence of the transition to a post-industrial society. Coincidentally, both transitions were accompanied by changes in the geopolitical position of the region. A structure consisting of organic multifunctional agriculture, innovative processing industries and domestic tourism should be created. As far as tourism is concerned, it should focus on combining different forms with an emphasis on enhancing experience and quality, but not exclusivity. The purpose is not to create jobs, but to change the way of life and the system of values of the local population.

Despite the establishment of Euroregions and the removal of some barriers, a significant economic impulse cannot be expected from cooperation with the Slovak side. At present, the development of Slovak–Czech cross-border cooperation is ensured mainly by the objectives of the INTERREG V-A Slovak Republic—Czech Republic Cooperation Program—which in the 2014–2020 programming period focused on four priority axes: exploitation of innovation potential, quality environment, development of local initiatives and technical assistance. The SK-CZ Regional Advisory Center Project plays an important role in all six regions on the Slovak–Czech border. Specific cooperation is mainly focused on the development of cross-border cultural tourism. These include the Cyril and Methodius Trail, support for the celebrations of the fraternity of Czechs and Slovaks at Velká Javorina Hill. Cycling routes and nature trails are being built, and the historical heritage in the border area is being restored. There are joint nature conservation projects, such as combating erosion and drying up wetlands. Cross-border cooperation is focused on tourism, cultural heritage and nature conservation corresponding to the geographical character of the studied area.

Of course, the results of this analysis could be further dissected. The situation may be different in different regions, and it would be possible to go into a more detailed view at the level of authorized municipal authorities. Candidates for a deeper analysis would be, for example, the micro-regions of Velká nad Veličkou, Slavičín, Bojkovice (

Figure 5), Brumov-Bylnice, and Karolinka, that is, micro-regions located directly on the border, which have indistinct centers. There would be scope for the use of other methods, such as qualitative sociological research methods, for example.