The Importance of Food Attributes and Motivational Factors for Purchasing Local Food Products: Segmentation of Young Local Food Consumers in Hungary

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Q1:

- What are the motives for purchasing local food from the perspective of young customers?

- Q2:

- Can motivational factors distinguish young customers into identifiable consumer groups? What are the motivational characteristics of the segments?

- Q3:

- Are local food consumption behaviours different among the different groups?

- Q4:

- Which socioeconomic and demographic factors are associated with a particular consumer segment?

2. Literature Review

- The role of uniqueness—the term “local” means that a food was produced or collected relatively close to where it is sold. A local product is produced mostly by small producers, using locally developed processes (recipes) or local materials. The packaging material is often locally produced, and the products reflect the characteristics and cultural heritage of the region.

- The role of local production—the term “local” means that the food products were produced by local labour, within a radius of about 50 km, to meet the needs of the local population (the role of local production) [23].

2.1. The Results of Surveys Conducted in Hungary

- A study of 1500 respondents aimed to determine the extent to which a product is considered domestic or comes from a local producer. This survey has shown that women are somewhat more patriotic than men. It identified a cluster of “those who like local specialities”, which comprises one-fifth of the respondents. Most of them are from the Northern Great Plain or Central Hungary, 48% of whom live in one-person households or are young people, undergraduates, or graduates. Moreover, 58% are men. Those belonging to this group consider the place of origin of the products (be it a Hungarian product or coming from a local producer) and the image of the product to be important [25].

- In 2017–2018, a national survey was conducted on a sample of 504 Hungarian people, and 82.9% of the respondents (418 persons) bought local products. The highest proportion of the respondents who bought local products were those who follow a lactose-free diet (94 people), representing 20.3% of the respondents. For the statement “I buy local products because …”, the highest average values were seen in answers (1) “I know where the product comes from”, (2) “I support local producers”, (3) “I support local sellers (traders)”, (4) “I can reduce the delivery distance of food miles”, and (5) “they are natural” [26].

- A total of 297 respondents living in Baranya and Tolna counties were the target of a survey in which the arguments in favour of buying local food products were examined. The respondents agreed to the importance of various factors: 28% of them mentioned trust, 27% knowing the place of origin, 26% supporting the local economy, 13% better quality, and 6% that the product is healthier. The research showed that consumers are receptive to novelties during their travels, and they are willing to try out ingredients and flavours that were previously unknown to them [27].

- Based on the results of research conducted in Zala and Somogy counties, quality and new experience are gaining more and more importance in the activities of local producers [28].

- Some 95% of the 152 young people surveyed in 2014 in Kaposvár, a town in Hungary, had already heard of the concept of local products, but only 50% of the respondents were fully aware of the exact meaning of the term. The majority of young people already bought local products, and 15% of the respondents bought local products weekly or even more often. They considered the best places to market such products were supermarkets, local marketplaces, hypermarkets, local product stores, and by shopping directly from the producers [29]. The most important features of local products based on the answers were as follows: naturalness, health, chemical- and preservative-free, origin, supporting local producers or sellers, shorter food miles, environmentally friendly nature of products, previous positive experiences, and free choice as to the quantity to be purchased as well as the appearance. Emotional factors include nostalgia for buying local products, having fun, remembering the old days, and “feeling of guilt over neglecting to buy local products”. The survey carried out among the young people of Kaposvár also identified the main attitudes related to local products. Based on the respondents’ evaluation, the following order was formed: (1) fresh; (2) evokes homemade flavours, traditional; (3) safe, healthy; (4) can be trusted; (5) environmentally friendly [29].

2.2. Consumers’ Purchasing Motivation towards Buying Local Food

3. Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Main Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

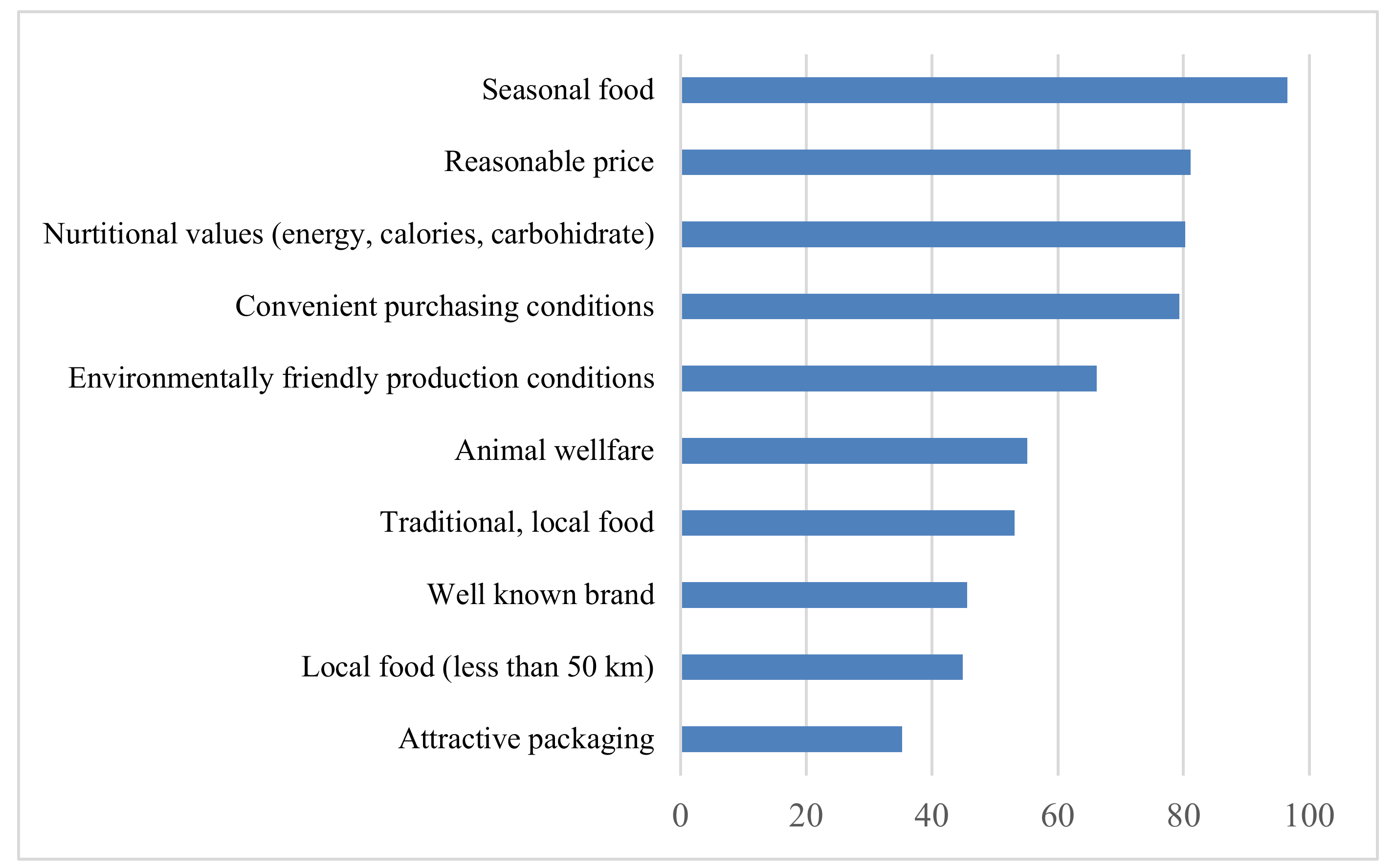

4.2. Product Attribute Preference Order

4.3. Consumer Motivations of Local Foods

4.4. Motivational Factors

4.5. Segmentation and the Description of Obtained Segments

- Cluster 1: The trend-follower (405 persons, 24%);

- Cluster 2: The distrustful (317 persons, 19%); and

- Cluster 3: The value-creator (973 persons, 57%).

- ◦

- They consider local products nutritious and healthy.

- ◦

- They trust local products and their origin.

- ◦

- They enjoy tasting local flavours.

- ◦

- They are less committed to choosing a local product.

- ◦

- Food is healthy.

- ◦

- They choose local, traditional, national food products.

- ◦

- Food is conveniently available.

- ◦

- They do not really trust local products.

- ◦

- They consider local products less nutritious and healthy.

- ◦

- It is less important for them to choose national or local products.

- ◦

- Food is healthy.

- ◦

- Food is conveniently available.

- ◦

- They trust local products and their origins.

- ◦

- They enjoy being able to taste local flavours.

- ◦

- They consider local products nutritious and healthy.

- ◦

- They are committed to buying local products.

- ◦

- The price of food is favourable.

- ◦

- To choose local, traditional, and national products.

- ◦

- Food is conveniently available.

5. Conclusions

- Boosts the local economy, supports local actors, and helps to lead them to environmentally and socially sustainable farming;

- Reduction in transport, energy consumption, and environmental pollution;

- Customers can acquire the products faster;

- The duration of storage is shortened;

- There is no need for artificial maturation, so consumers can purchase fresher, healthier food;

- The use of packaging material is reduced, so less waste is generated;

- Local producers are progressing; and

- Trust is growing, which is one of the main cohesive forces in the relationship among consumers and producers.

- The “trend-followers” are driven by conscience; although they trust local products and their origins, they are less committed to buying local products.

- For the second cluster (“distrustful”), it is less important to choose a national or a local product; for them, convenience is the most important factor.

- The third cluster (“value-creator”) is especially committed to buying local products and discovering and learning about new things.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barska, A.; Wojciechowska-Solis, J. E-Consumers and Local Food Products: A Perspective for Developing Online Shopping for Local Goods in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAK (National Chamber of Agriculture): Rövid Ellátási Lánc a Gyakorlatban. 2020. Available online: https://www.nak.hu/tajekoztatasi-szolgaltatas/rel-egyuttmukodes/102501-rovid-ellatasi-lanc-a-gyakorlatban (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Kislépték Egyesület. REL Szervezők Napja—Amit a Helyi Termékek Értékesítéséről Tudni Kell. 2022. Available online: https://kisleptek.hu/hirek/rel-szervezok-napja-amit-a-helyi-termekek-ertekesiteserol-tudni-kell/ (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Augère-Granier, M. Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in the EU. European Parliamentary Research Service Briefing. 2016. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2016/586650/EPRS_BRI(2016)586650_EN.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Nagy-Pető, D. A helyi termékek fogyasztói preferenciáinak vizsgálata (Examining consumer preferences of local products). Táplálkozásmarketing 2021, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Kim, J.O. The investigation of Chinese consumer values, consumption values, life satisfaction and consumption behaviors. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ölander, F. Human values and the emergence of a sustainable consumption pattern: A panel study. J. Econ. Psychol. 2002, 23, 605–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Holland, R.W. Motivated decision making: Effects of activation and self-centrality of values on choices and behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Jha, M. Values influencing sustainable consumption behaviour: Exploring the contextual relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 76, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kallas, Z. Meta-analysis of consumers’ willingness to pay for sustainable food products. Appetite 2021, 163, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazdecki, M.; Goryńska-Goldmann, E.; Kiss, M.; Szakály, Z. Segmentation of Food Consumers Based on Their Sustainable Attitude. Energies 2021, 14, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osztovics, Á.; Séra, E.; Perger, J. Új Generációk, új Fogyasztók, új Válaszok; PricewaterhouseCoopers: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, Short-Term Outlook for EU Agricultural Markets in 2020. Available online: https://www.short-term-outlook-autumn-2020_en.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Ewing-Chow, D. Five Ways That Coronavirus Will Change the Way We Eat. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/daphneewingchow/2020/03/31/five-ways-that-coronavirus-will-change-the-way-we-eat/?sh=52a998f41a2b (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Deloitte. COVID-19 Has Broken the Global Food Supply Chain. So Now What? Reshaping Food Supply Chains to Prepare for the Post-Outbreak Era. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/nl/nl/pages/consumer/articles/food-covid-19-reshaping-supply-chains.html (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Dogi, I.; Nagy, L.; Csipkés, M.; Balogh, P. Kézműves élelmiszerek vásárlásának fogyasztói magatartásvizsgálata a nők körében. Gazdálkodás 2014, 58, 16–172. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, R. Protecting the EU Agri-Food Supplychain in the Face of COVID-19. European Parliamentary Research Service Briefing 2020. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/649360/EPRS_BRI(2020)649360_EN.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Kneafsey, M.; Venn, L.; Schmutz, U.; Balasz, B.; Trenchard, L.; Eyden-Wood, T.; Bos, E.; Sutton, G.; Blackett, M.; Santini, F.; et al. (Eds.) Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in the EU. A State of Play of their Socio-Economic Characteristics. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haugum, M.; Grande, J. The Role of Marketing in Local Food Networks. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. Int. Cent. Manag. Commun. Res. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, J.R.; Joshua, T.B.; John, P. Food as Ideology: Measurement and Validation of Locavorism. J. Consum. Res. 2018, 45, 849–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEUC.eu One Bite at a Time: Consumers and the Transition to Sustainable Food the European Consumer Organisation 2020. Available online: https://www.beuc.eu/publications/beuc-x-2020–042_consumers_and_the_transition_to_sustainable_food.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- NEBIH. Képes Tanúsító Védjegy Kereső. Nemzeti Élelmiszerlánc-Biztonsági Hivatal 2021. Available online: https://portal.nebih.gov.hu/kepes-vedjegy-kereso (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Fekete, É. Helyi Termékek Előállítása és Értékesítése a Zala Termálvölgyében. Kutatási Zárótanulmány. Zala Termálvölgye Egyesület. Available online: http://uj.zalatermalvolgye.hu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/helyi_termek_tanulmany_zalatermalvolgye_0.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Szente, V.; Jasák, H.; Szűcs, A.; Kalmár, S. Helyi élelmiszerek fogyasztói megítélése. Gazdálkodás 2014, 5, 452–494. [Google Scholar]

- Malota, E.; Gyulavári, T.; Bogáromi, E. Mutimiteszel Élelmiszer Vásárlási és Fogyasztási Preferenciák, Étkezési Szokások a Magyar Lakosság Körében. Available online: http://unipub.lib.uni-corvinus.hu/3695/ (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Barna, F.K.; Bauerné Gáthy, A.; Kovács, B.; Szakály, Z. Az alternatív étrendet követők helyi termékek vásárlásához kapcsolódó attitűdjei. Táplálkozásmarketing 2018, 5, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, D. A Helyi Termékek Fogyasztói Megítélése a 4C Marketing Megközelítésben, Kérdőíves Kutatás a Helyi Tsermékek Megítélésének Feltérképezésére a Dél-Dunántúli Helyi Termelők és Fogyasztók Körében. Gyeregyalog.hu Egyesület. 2018. Available online: https://eatgreen.hu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Helyi_termek_4C_tanulmany_HU.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Tóth-Kaszás, N.; Keller, K.; Péter, E. Zala és Somogy megyei helyi termelőkben rejlő fejlesztési lehetőségek feltárása. A FALU 2017, 32, 1. Available online: http://helyitermek.zalatermalvolgye.hu/node/1920 (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Sántosi, P.; Böröndi-Fülöp, N. Helyi termékek fogyasztása és megítélése kaposvári fiatalok körében. Élelmiszer Táplálkozás Mark. 2014, 10, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S.; Lobb, A.E.; Butler, L.; Harvey, K.; Traill, W.B. Local, national and imported foods: A qualitative study. Appetite 2007, 49, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roininen, K.; Arvola, A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Exploring consumers’ perceptions of local food with two different qualitative techniques: Laddering and word association. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.J. Farmers’ markets as retail spaces. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2011, 39, 582–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellows, A.C.; Alcaraz, G.V.; Hallman, W.K. Gender and food, a study of attitudes in the USA towards organic, local, U.S. grown, and GM-Free foods. Appetite 2010, 55, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selfa, T.; Qazi, J. Place, taste, or face-to-face? Understanding producer–consumer networks in “local” food systems in Washington State. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, R.; Raffaelli, R.; Thilmany, D.D. Consumer preferences for fruit and vegetables with credence-based attributes: A review. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Arsil, P.; Li, E.; Bruwer, J.; Lyons, G. Exploring consumer motivations towards buying local fresh food products: A means-end chain approach. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1533–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherell, C.; Tregear, A.; Allinson, J. In search of the concerned consumer: UK public perceptions of food, framing and buying local. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, S.; Sheena, D. Sustainability Transitions in University Food Service—A Living Lab Approach of Locavore Meal Planning and Procurement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Hassan, L.M. The role of health consciousness, food safety concern and ethical identity in attitudes and intentions towards organic food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.Y.J.; Kim, S.S. Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, M.; Nejad, N.S.; Azad, F.T.; Taheri, B.; Gannon, M.J. Food consumption experiences: A framework for understanding food tourists’ behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Lin, S.H.-H.; Wu, L.-S. Searching memories of pleasures in local cuisine: How nostalgia and hedonic values affect tourists’ behavior at hot spring destinations? Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Çalışkan, C.; Sabbağ, Ç. Local food consumption during travel: Interaction of incentive-disincentive factors, togetherness, and hedonic value. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. Tourism and hospitality marketing: Fantasy, feeling and fun. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 18, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, X.X.; Cai, S.; Scott, N. Vegan tours in China: Motivation and benefits. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Ma, J.; Lee, Y.S. How do Chinese travelers experience the Arctic? Insights from a hedonic and eudaimonic perspective. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 20, 144–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.T. Memorable tourist experiences and place attachment when consuming local food. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Mortimer, G. Drivers of local food consumption: A comparative study. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 2282–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dukeshire, S.; Garbes, R.; Kennedy, C.; Boudreau, A.; Osborne, T. Beliefs, attitudes, and propensity to buy locally produced food. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2011, 1, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memery, J.; Angell, R.; Megicks, P.; Lindgreen, A. Unpicking motives to purchase locally-produced food: Analysis of direct and moderation effects. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 1207–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareklas, I.; Carlson, J.R.; Muehling, D.D. I Eat Organic for My Benefit and Yours: Egoistic and Altruistic Considerations for Purchasing Organic Food and Their Implications for Advertising Strategists. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.J. Evaluating local food programs: The case of Select Nova Scotia. Eval. Program Plan. 2013, 36, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. Growing sustainable consumption communities: The case of local organic food networks. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2007, 27, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregear, A.; Ness, M. Discriminant analysis of consumer interest in buying locally produced foods. J. Mark. Manag. 2005, 21, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C.; Larson, L.R.; Tidball, K.G.; Tidball, M.; Curtis, P.D. Hunting and the local food movement: Insights from central New York State. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2017, 41, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlhausen, J.L.; Rungie, C.; Roosen, J. Value of labeling credence attributes—Common structures and individual preferences. Agric. Econ. 2018, 49, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardi, P.; Bertello, A.; Venuti, F. Community-Oriented motivations and knowledge sharing as drivers of success within food assemblies. In Exploring Digital Ecosystems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 443–457. [Google Scholar]

- Pascucci, S. Governance structure, perception, and innovation in credence food transactions: The role of food community networks. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2010, 1, 224–236. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, D.; Memery, J. Tourists, local food and the intention-behaviour gap. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muça, E.; Iwona, P.; Mariya, P. The Role of GI Products or Local Products in the Environment—Consumer Awareness and Preferences in Albania, Bulgaria and Poland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, S.B.; Akoglu, A. Assessment of local food use in the context of sustainable food: A research in food and beverage enterprises in Izmir, Turkey. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 20, 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesić, Ž.; Petljak, K.; Borović, D.; Tomić, M. Segmentation of local food consumers based on altruistic motives and perceived purchasing barriers: A Croatian study. Econ. Res. 2020, 34, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, I.; Lehota, J.; Komaromi, N. Analysis of the characteristics of the sustainable food consumption in Hungary. In Proceedings of the EMOK XXII Országos Konferencia 2016, Debrecen, Hungary, 30–31 August 2016; pp. 686–694. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, I. Sustainable food consumption intentions related to food safety among young adults. Analecta Tech. Szeged 2020, 14, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intrinsic | Extrinsic | |

|---|---|---|

| Qualities and societal benefits | quality, appearance, freshness, taste, healthiness, safety, and being associated with egoistic motivations or self-interest | supporting local producers, retailers, and economies, preserving agricultural land, increased food security with altruistic motivations or contributing to the “wider good”. |

| Motivational factors | product-related factors are discussed in [30,31,32,33] nostalgia for shopping, fun, and memories of old times [29] health consciousness [34,35,36,37,38] quality of life and well-being [39] emotional values and motivations [40] hedonic: culinary tourism [41,42] togetherness and novelty of food [43] health consciousness, e.g., nutritional value [34,35,42] taste, freshness [30,31,32] togetherness and novelty of food [43] tourism products as purely hedonic consumption experiences [44,45] effective ways of creating hedonic and memorable experience [46] self-rewarding experience [47] | support for local farmers, producers and retailers [48,49,50] environmental and social motivation [51,52,53] environmental concerns [51,54] animal welfare, environmental sustainability, supporting rural communities [55] animal welfare [56] community-oriented motivations and motivations for participation in a community-supported agriculture scheme [41,48,49,50,57,58] local heritage [59,60] community-oriented motivations [41,57] |

| Not at All | Rather Not | Rather Yes | Very Much | TOP2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I enjoy discovering new foods. | 2.60 | 10.90 | 60.00 | 26.60 | 86.60 |

| It’s a pleasure for me to try. | 2.80 | 10.50 | 63.70 | 23.10 | 86.80 |

| I would like to know more about local flavours. | 4.10 | 15.80 | 61.10 | 19.00 | 80.10 |

| I am curious, I love getting to know new flavours. | 2.60 | 12.20 | 57.50 | 27.70 | 85.20 |

| I think these products are healthy. | 5.10 | 19.50 | 61.10 | 14.40 | 75.50 |

| These products are nutritious. | 6.60 | 27.10 | 54.70 | 11.50 | 66.20 |

| I trust this product because I know where it comes from. | 4.80 | 12.90 | 60.60 | 21.80 | 82.40 |

| I trust this product because it has a long tradition. | 7.00 | 21.80 | 54.40 | 16.70 | 71.10 |

| Scale Items | Curiosity | Nutritional Value | Pleasure | Risk Aversion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am curious, I love getting to know new flavours. | 0.902 | 0.215 | 0.507 | 0.196 |

| I would like to know more about local flavours. | 0.891 | 0.177 | 0.554 | 0.292 |

| These products are nutritious. | 0.160 | 0.888 | 0.252 | 0.455 |

| I think these products are healthy. | 0.165 | 0.845 | 0.392 | 0.513 |

| I enjoy discovering new foods. | 0.470 | 0.295 | 0.878 | 0.415 |

| It’s a pleasure for me to try. | 0.580 | 0.291 | 0.832 | 0.329 |

| I trust this product because I know where it comes from. | 0.253 | 0.471 | 0.356 | 0.917 |

| I trust this product because it has a long tradition. | 0.167 | 0.531 | 0.524 | 0.792 |

| Cluster | Error | F | Sig. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale Items | Mean Square | df | Mean Square | df | ||

| I enjoy discovering new foods. | 95.450 | 2 | 0.356 | 1692 | 267.743 | 0.000 |

| It’s a pleasure for me to try. | 91.220 | 2 | 0.337 | 1692 | 270.419 | 0.000 |

| I would like to know more about local flavours. | 117.928 | 2 | 0.370 | 1692 | 318.755 | 0.000 |

| I am curious, I love getting to know new flavours. | 118.938 | 2 | 0.351 | 1692 | 338.879 | 0.000 |

| I think these products are healthy. | 136.766 | 2 | 0.355 | 1692 | 384.973 | 0.000 |

| These products are nutritious. | 165.068 | 2 | 0.373 | 1692 | 442.879 | 0.000 |

| I trust this product because I know where it comes from. | 152.431 | 2 | 0.354 | 1692 | 430.479 | 0.000 |

| I trust this product because it has a long tradition. | 245.754 | 2 | 0.342 | 1692 | 718.533 | 0.000 |

| Scale Items | Cluster | Not at All (%) | Rather Not (%) | Rather Yes (%) | Very Much (%) | Gamma Value | Approximate Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I enjoy discovering new foods. | Trend-follower | 5.7 | 24.7 | 67.2 | 2.5 | 0.725 | 0.000 |

| Distrustful | 6.0 | 23.7 | 55.8 | 14.5 | |||

| Value-creator | 0.2 | 1.0 | 58.1 | 40.7 | |||

| It’s a pleasure for me to try. | Trend-follower | 3.0 | 22.2 | 72.3 | 2.5 | 0.708 | 0.000 |

| Distrustful | 11.4 | 24.0 | 55.8 | 8.8 | |||

| Value-creator | 0.0 | 1.3 | 62.5 | 36.2 | |||

| I would like to know more about local flavours. | Trend-follower | 6.4 | 39.5 | 52.6 | 1.5 | 0.744 | 0.000 |

| Distrustful | 12.6 | 27.4 | 52.1 | 7.9 | |||

| Value-creator | 0.3 | 2.2 | 67.6 | 29.9 | |||

| I am curious, I love getting to know new flavours. | Trend-follower | 5.2 | 34.6 | 59.8 | 0.5 | 0.777 | 0.000 |

| Distrustful | 6.9 | 18.3 | 58.0 | 16.7 | |||

| Value-creator | 0.0 | 1.0 | 56.3 | 42.7 | |||

| I think these products are healthy. | Trend-follower | 3.0 | 23.0 | 67.4 | 6.7 | 0.508 | 0.000 |

| Distrustful | 21.1 | 50.8 | 28.1 | 0.0 | |||

| Value-creator | 0.6 | 7.7 | 69.4 | 22.3 | |||

| These products are nutritious. | Trend-follower | 2.0 | 33.1 | 59.5 | 5.4 | 0.468 | 0.000 |

| Distrustful | 26.5 | 64.4 | 8.5 | 0.6 | |||

| Value-creator | 2.0 | 12.9 | 67.5 | 17.6 | |||

| I trust this product because I know where it comes from. | Trend-follower | 1.2 | 12.3 | 75.3 | 11.1 | 0.504 | 0.000 |

| Distrustful | 21.8 | 40.7 | 37.5 | 0.0 | |||

| Value-creator | 0.5 | 3.9 | 62.1 | 33.5 | |||

| I trust this product because it has a long tradition. | Trend-follower | 0.2 | 25.9 | 63.0 | 10.9 | 0.463 | 0.000 |

| Distrustful | 35.6 | 56.8 | 7.6 | 0.0 | |||

| Value-creator | 0.5 | 8.6 | 66.0 | 24.9 |

| Product Attributes | Cluster 1 (Trend-Follower) | Cluster 2 (Distrustful) | Cluster 3 (Value-Creator) |

|---|---|---|---|

| It should be conveniently available. | 3.98 | 3.96 | 4.05 |

| It should be local food. | 3.33 | 2.96 | 3.62 |

| The properties of the food (e.g., nutrient, vitamin, energy content). | 3.95 | 3.8 | 4.13 |

| Food should be healthy (e.g., vitamins, mineral, sugar, fat, and antioxidants content). | 3.97 | 3.83 | 4.29 |

| Environmental protection during production. | 3.71 | 3.5 | 3.98 |

| Animal welfare standards (e.g., free-range). | 3.48 | 3.3 | 3.83 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovács, I.; Balázsné Lendvai, M.; Beke, J. The Importance of Food Attributes and Motivational Factors for Purchasing Local Food Products: Segmentation of Young Local Food Consumers in Hungary. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3224. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063224

Kovács I, Balázsné Lendvai M, Beke J. The Importance of Food Attributes and Motivational Factors for Purchasing Local Food Products: Segmentation of Young Local Food Consumers in Hungary. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3224. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063224

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovács, Ildikó, Marietta Balázsné Lendvai, and Judit Beke. 2022. "The Importance of Food Attributes and Motivational Factors for Purchasing Local Food Products: Segmentation of Young Local Food Consumers in Hungary" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3224. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063224

APA StyleKovács, I., Balázsné Lendvai, M., & Beke, J. (2022). The Importance of Food Attributes and Motivational Factors for Purchasing Local Food Products: Segmentation of Young Local Food Consumers in Hungary. Sustainability, 14(6), 3224. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063224