Work-Family Interface in the Context of Social Responsibility: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

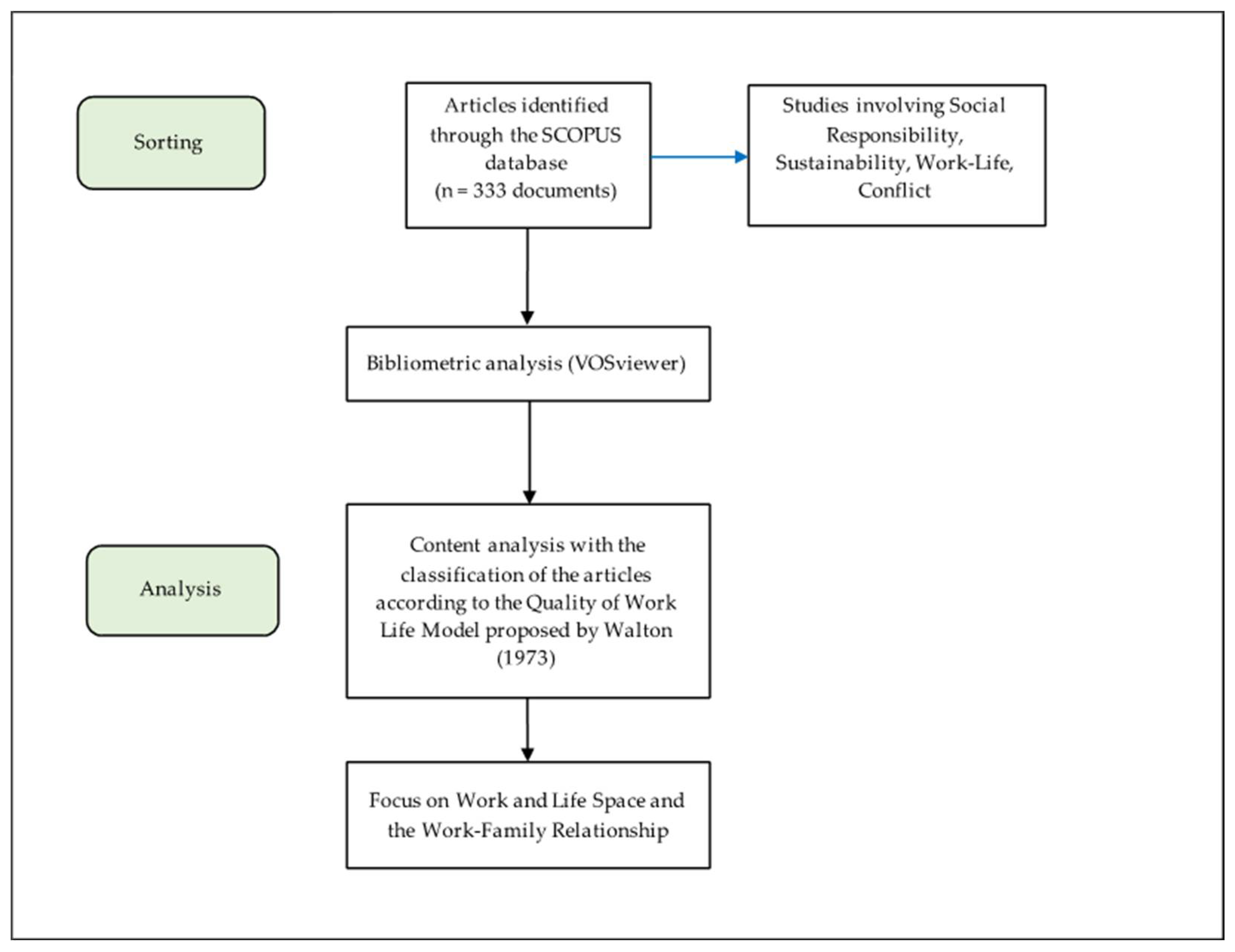

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

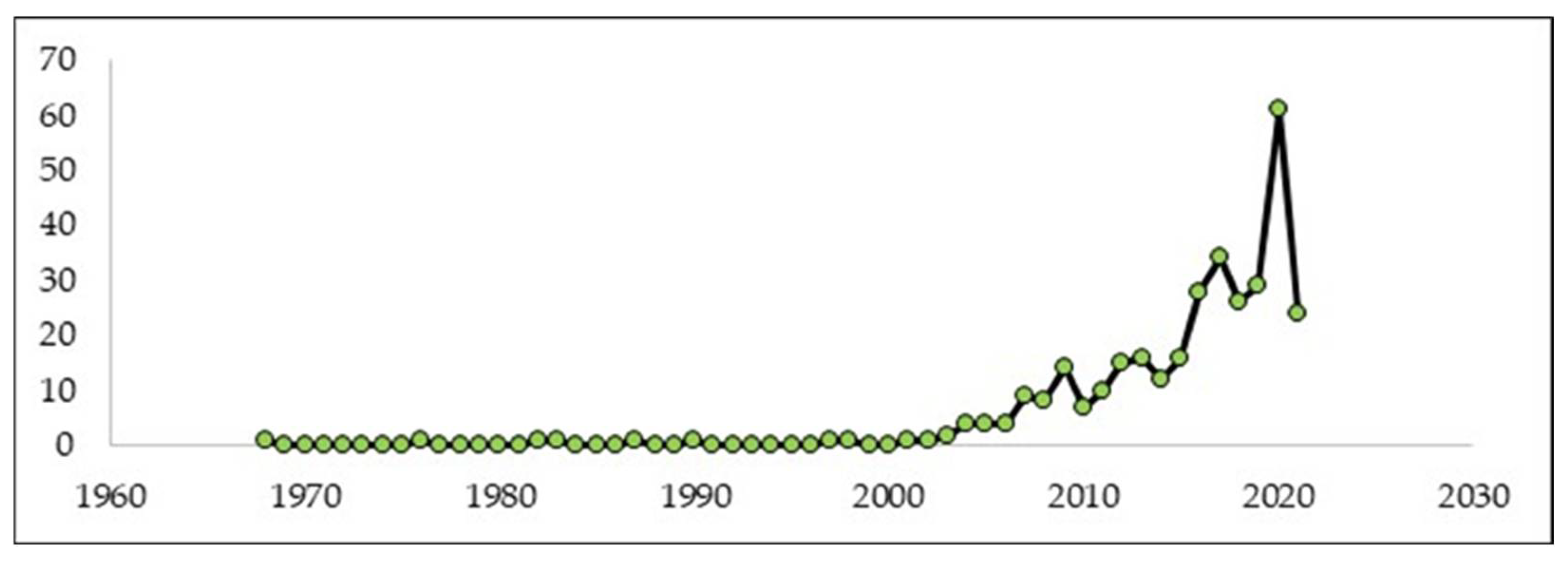

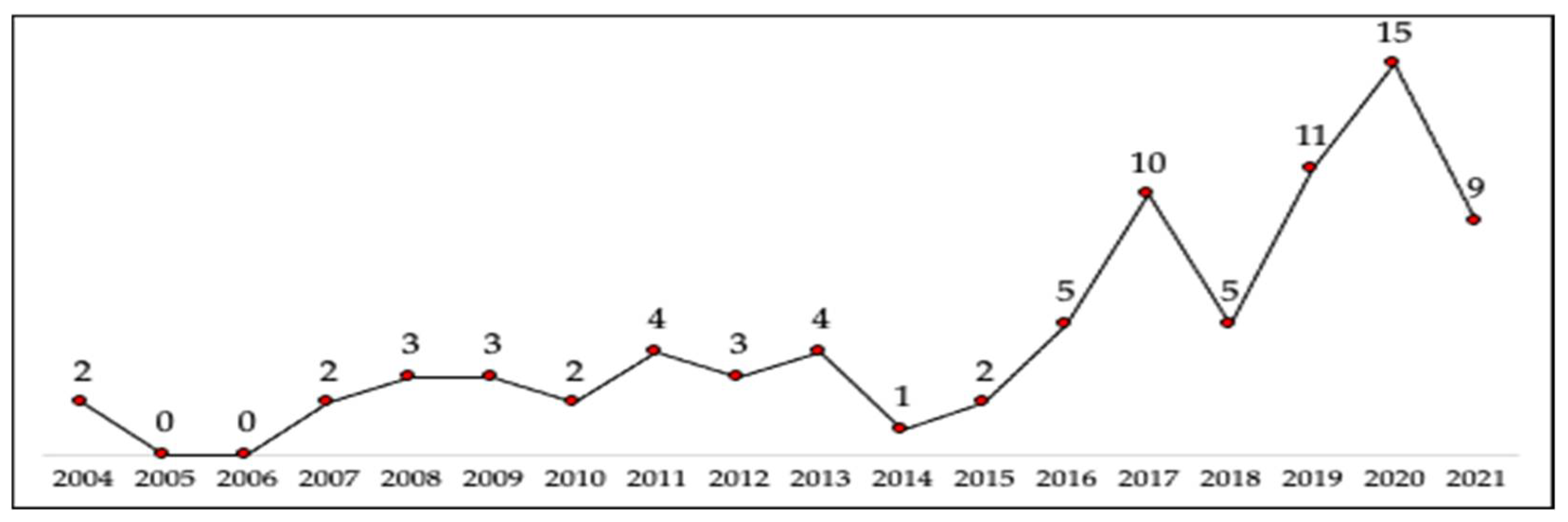

4.1. Bibliometric Analysis

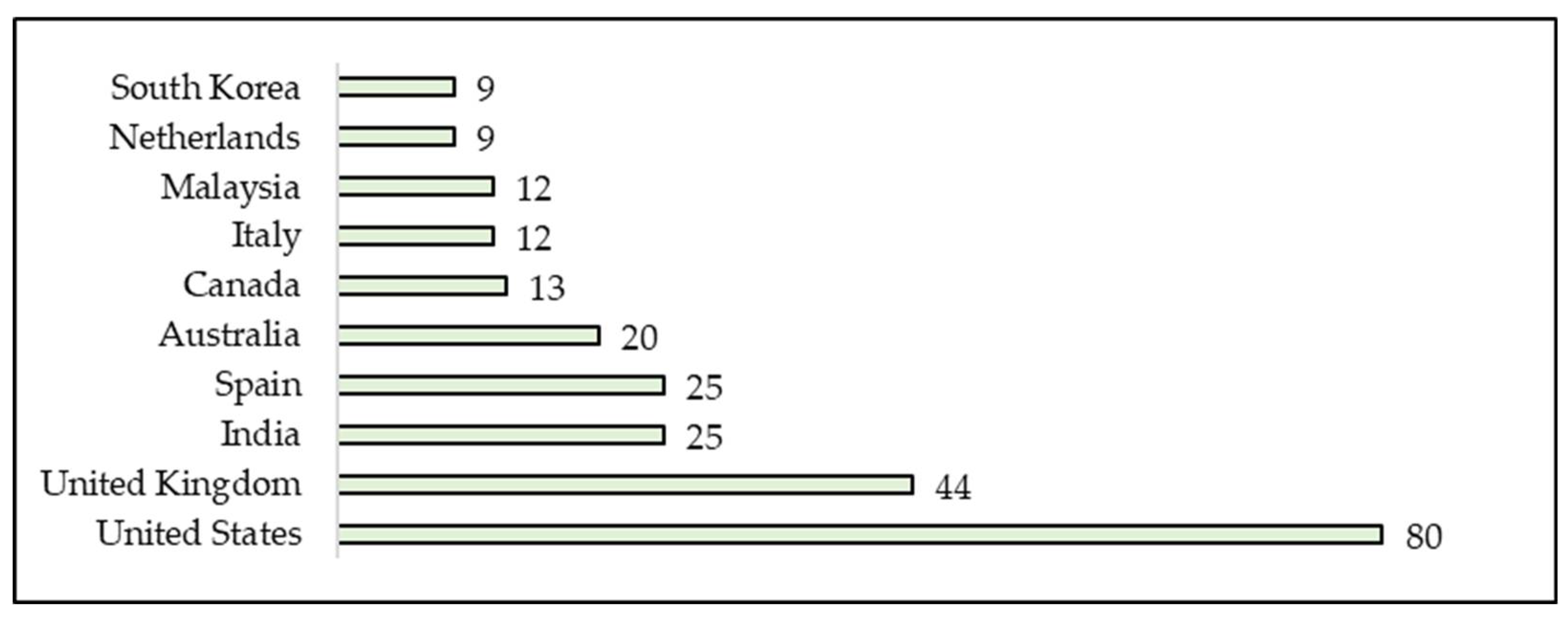

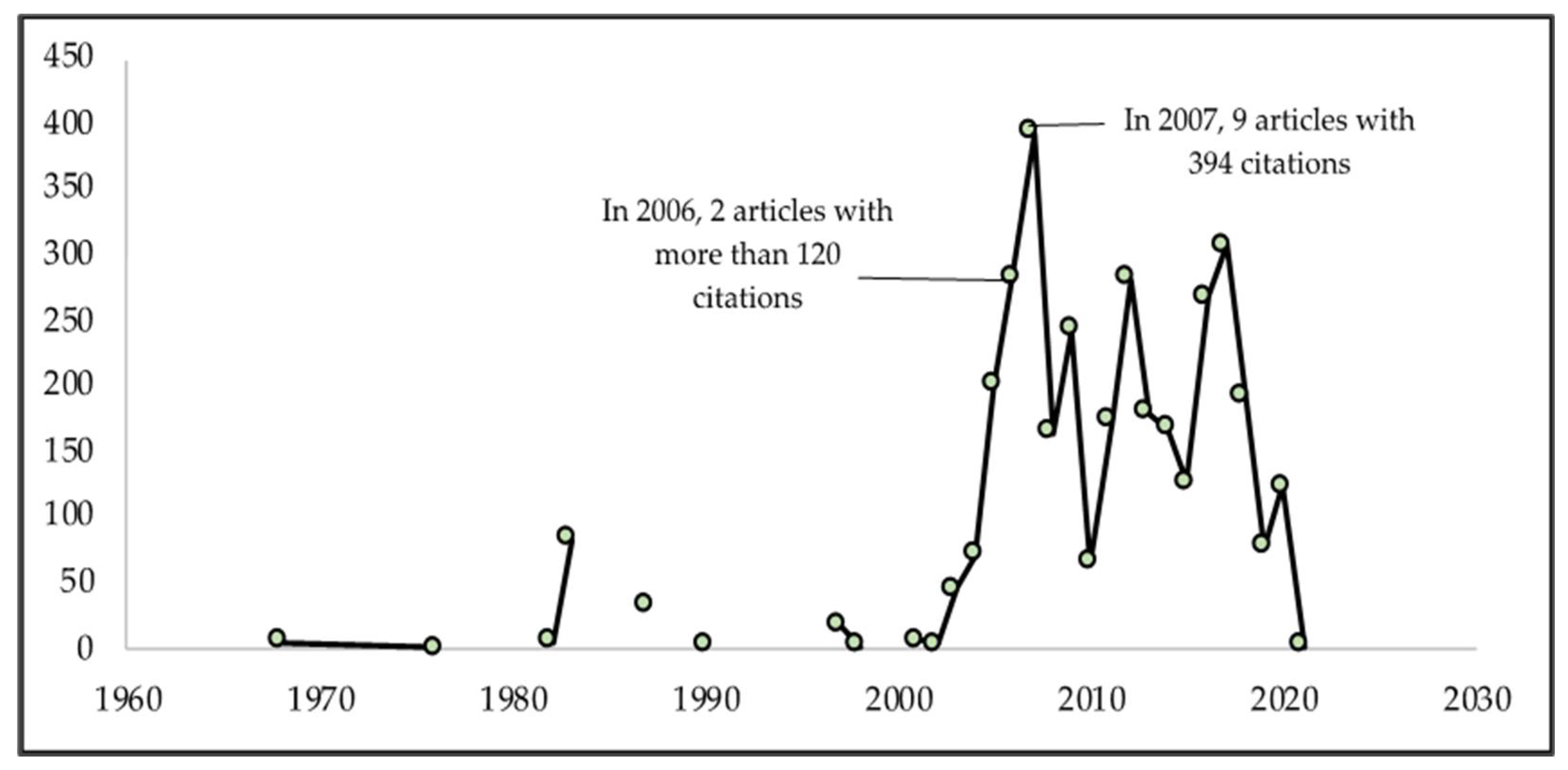

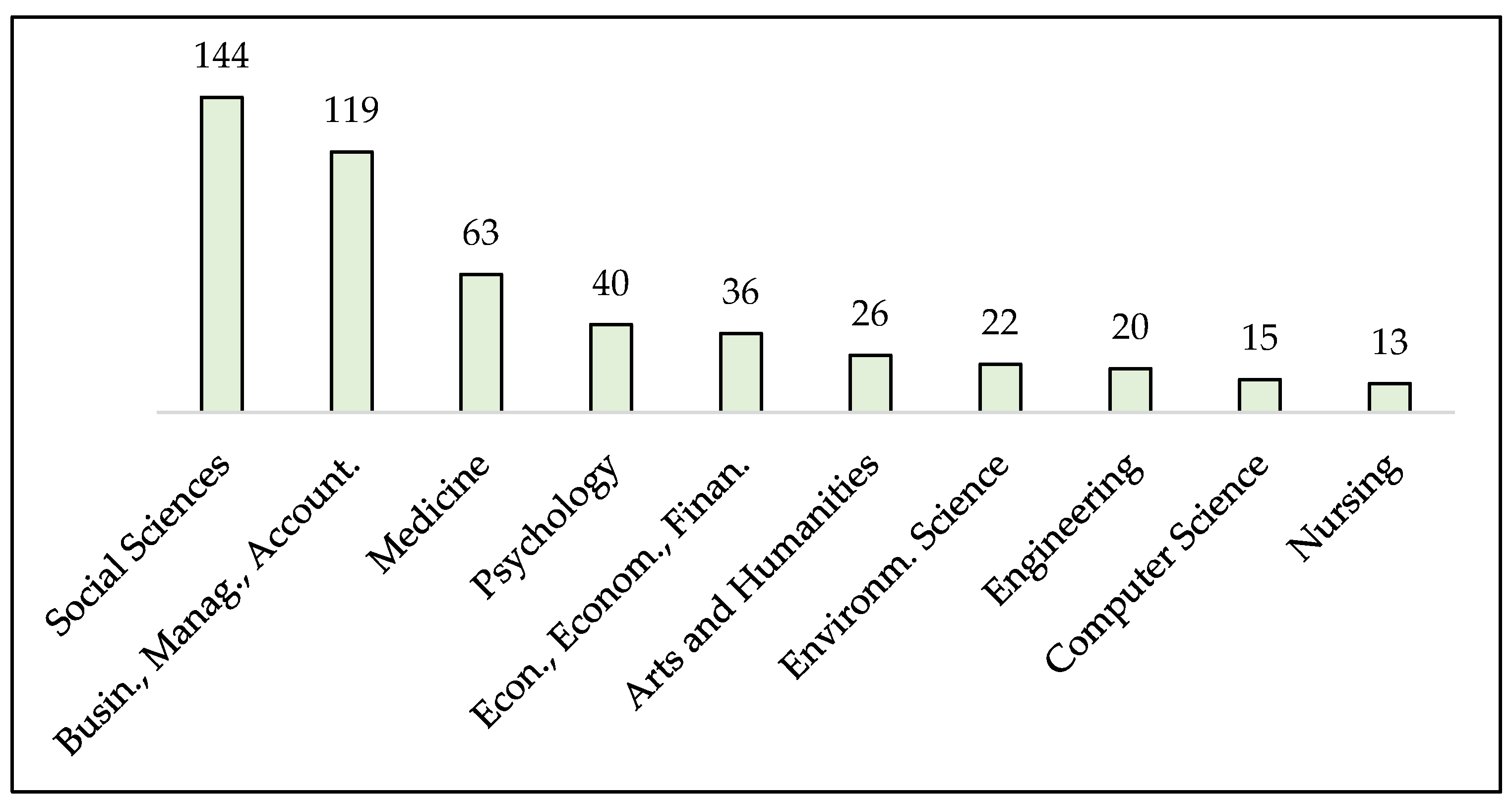

4.1.1. Publications, Countries, Citations, Journals, and Research Areas

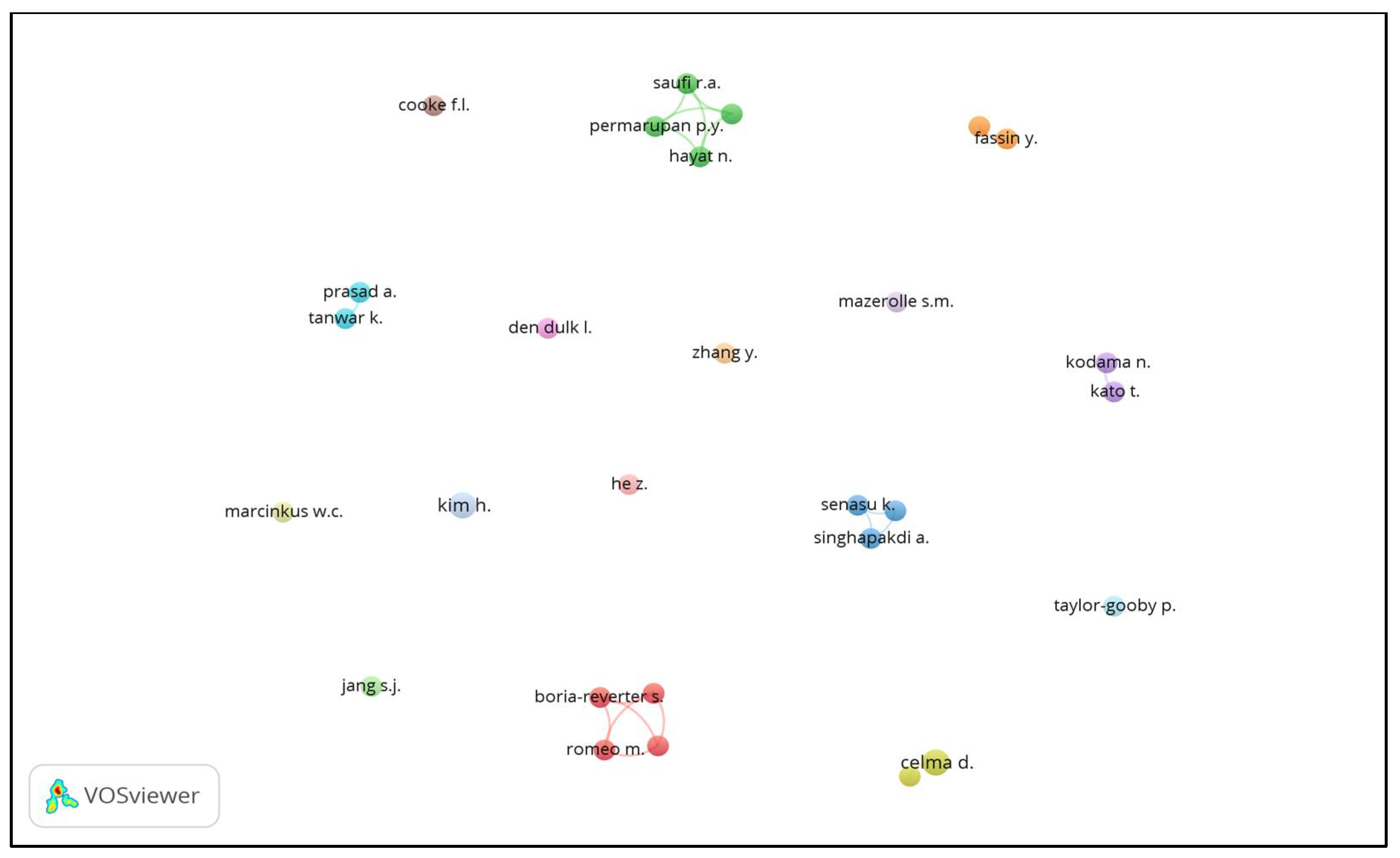

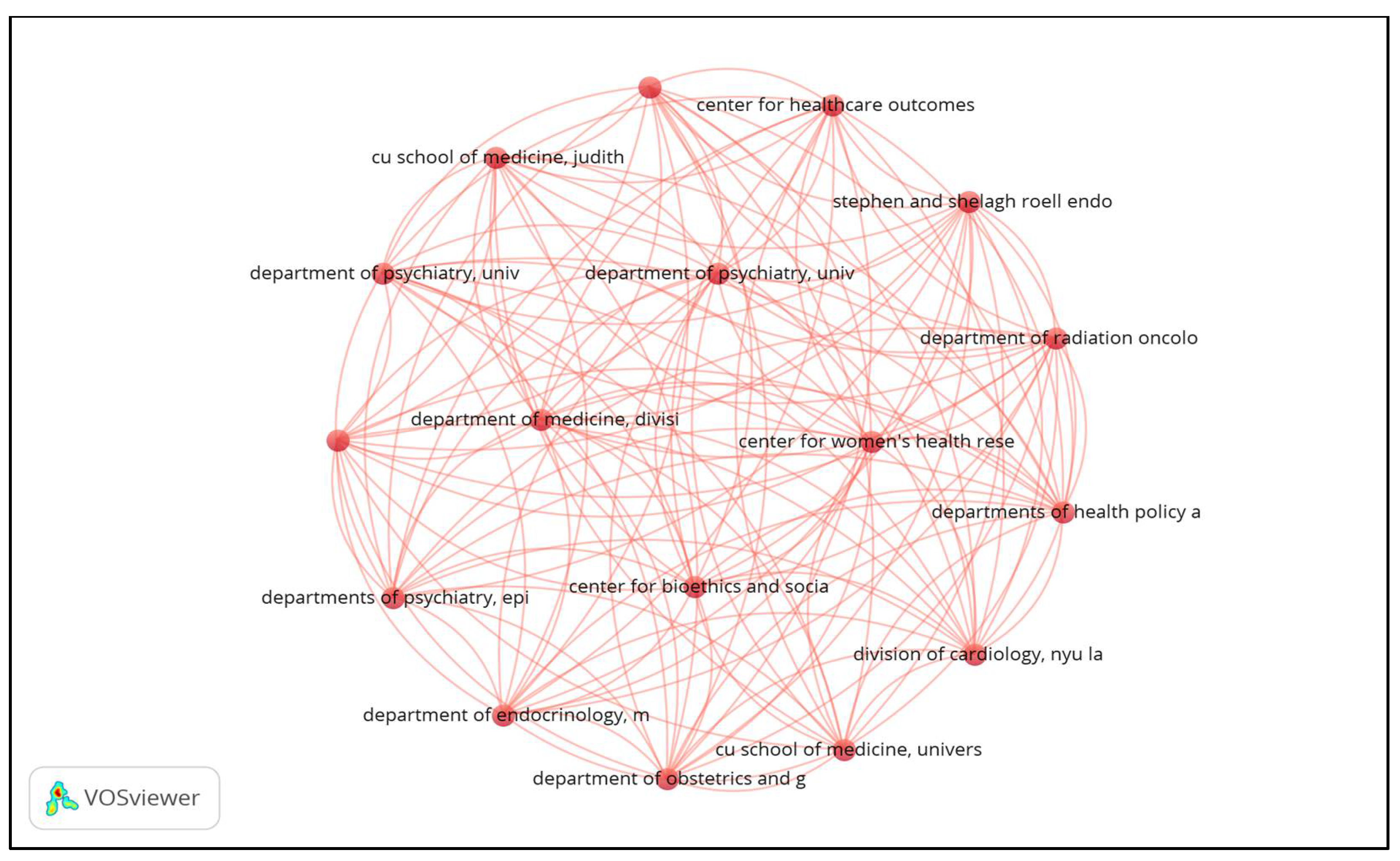

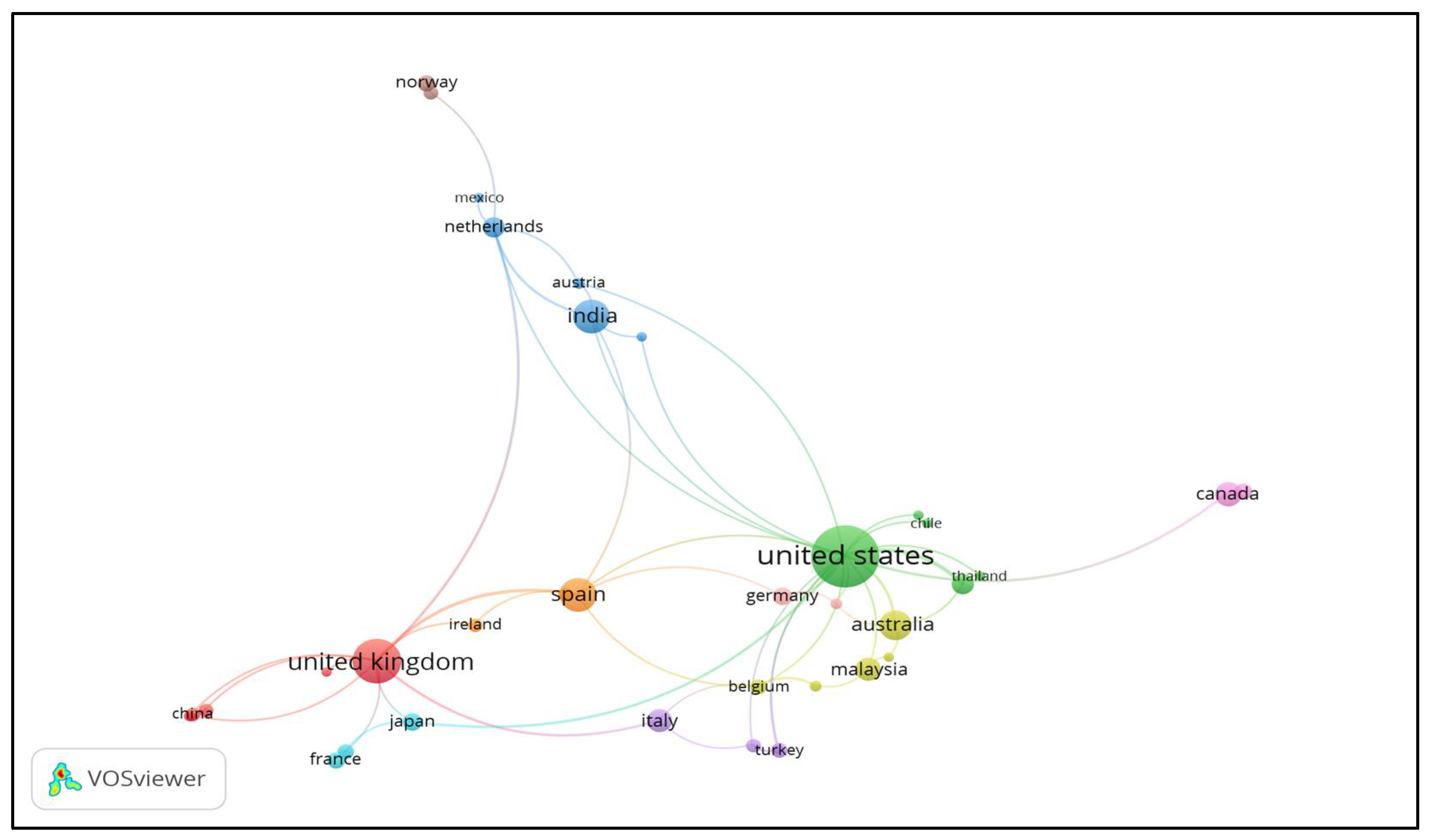

4.1.2. Publications by Author, Institution, and Country

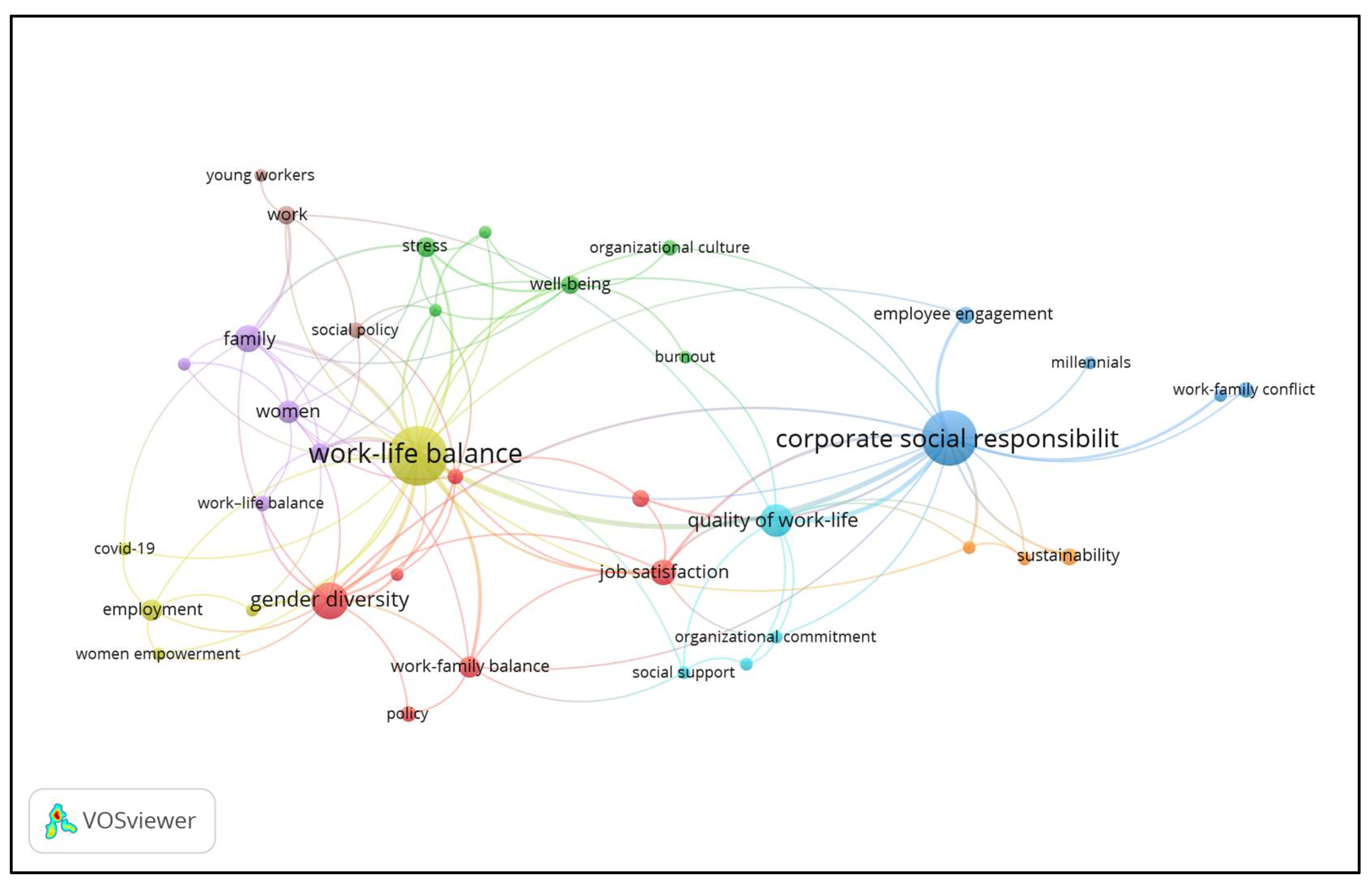

4.1.3. Keyword Analysis

4.2. Work and Living Space Dimension and the Work-Family Relationship

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimension | Quant. of Articles | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|

| Social Integration | 51 | Mitcheltree, 2021; Espasandín-Bustelo, Ganaza-Vargas & Diaz-Carrion, 2021; Carpenter et al., 2021; Bruffaerts et al., 2021; [No author name available 1], 2021; [No author name available 4], 2021; Gupta, Bhasin & Mushtaq, 2021; Reverberi et l., 2021; Parlak, Celebi Cakiroglu & Oksuz Gul, 2021; Lee, 2021; Smith & Solano, 2020; Álvarez-Pérez et al., 2020; Hirsh, Treleaven & Fuller, 2020; Nazir & Islam, 2020; Ruparelia et al., 2020; Schiavo, Leonardi & Zancanaro, 2020; Satyen, van Dort & Yin, 2020; Kromydas, 2020; Salminen, Wang & Aaltio, 2019; Miller, 2019; Lulle, 2018; Kato & Kodama, 2018; Novich & Garcia-Hallett, 2018; Bahiru & Mengistu, 2018; Lefrançois, Saint-Charles & Riel, 2017; Baylina et al., 2017; McDonald, Kehler & Tough, 2016; Machado & Paulo Davim, 2016; Singhapakdi et al., 2015; Agarwala et al., 2014; Cheng & McCarthy, 2013; Mazerolle & Goodman, 2012; Longenecker, Beard & Scazzero, 2012; Voxted & Lind, 2012; Reilly, Sirgy & Gorman, 2012; Schnurr & Zayts, 2012; Brown, 2011; Valk & Srinivasan, 2011; Yerkes et al., 2010; Moore & Wen, 2009; Johnson, Andrey & Shaw, 2007; Armstrong et al., 2007; Marcinkus & Hamilton, 2006; Kilian, Hukai & McCarty, 2005; Taylor-Gooby & Larsen, 2005; MacInnes, 2005; Gentili, Stainer & Stainer, 2003; Collier, 2001; Bird & Waters, 1987; Strand, 1983. |

| Opportunity to use and develop human capacity | 29 | Plummer et al., 2021; Gutiérrez-Vargas et al., 2020; Banta & Pratt, 2020; Chaudhry et al., 2019; Dima et al., 2019; Ishak et al., 2018; Llinares-Insa et al., 2018; Unsworth, 2018; Cooke, 2018; Rajasekar & Deepa, 2017; Nottingham, Mazerolle & Barrett, 2017; Drinkwater, 2017; Treister-Goltzman & Peleg, 2016; Boström et al., 2016; Kasch et al., 2016; Solbrekke et al., 2016; McKenna, Verreynne & Waddell, 2016; Thang & Fassin, 2016; Darrah, Conand & Dornadic, 2015; Campbell-Barr & Coakley, 2014; Pollitt, 2013; Maier et al., 2013; Wintrup et al., 2012; Barron & D’Annunzio-Green, 2009; Bolat & Yılmaz, 2009; Zhang, Straub & Kusyk, 2007; Knox & Irving, 1997; MacFarlane, 1990; Johnstone, 1968. |

| Safety and health in working conditions | 42 | Adu-Gyamfi et al., 2021; Uhlig-Reche et al., 2021; Cathelain et al., 2020; Scheepstra et al., 2020; Permarupan et al., 2020; Dudutienė, Juodaitė-Račkauskienė & Stukas, 2020; French & Shockley, 2020; Ventriglio, Watson & Bhugra, 2020; Campbell & Gunning, 2020; Permarupan et al., 2020; Salehi, Seyyed & Farhangdoust, 2020; Marek et al., 2019; Bostock, 2019; Celma, Martinez-Garcia & Raya, 2018; Zarea et al., 2018; Kim & Cho, 2017; Been, den Dulk & van der Lippe, 2017; Dirkse van Schalkwyk & Steenkamp, 2017; Zhang, Punnett & Nannini, 2017; Dan & Kohiyama, 2017; Živčicova, Bulková & Masárová, 2017; Wilkin, Fairlie & Ezzedeen, 2016; Cooper, 2016; Ahmad et al., 2016; Inoue, Nishikitani & Tsurugano, 2016; Ethel, Ziska & Olusegun, 2016; Eikeland, 2015; Paterson et al., 2015; Tung et al., 2015; Zientara, 2014; Petree, Broome & Bennett, 2012; Gidman et al., 2011; Sekine et al., 2010; Griffith & Tengnah, 2010; Mah, 2009; Draper, 2008; Still, 2008; Poelmans & Beham, 2008; Katz & Lazcano-Ponce, 2008; Bernard & Phillips, 2007; Fitch & Allard, 2007; Ducki, 2002. |

| Constitutionalism | 32 | Golob & Podnar, 2021; Molnár et al., 2021; Bhattacharya & Gandhi, 2020; Coron, 2020; Chamberlain et al., 2020; Dvorakova & Kulachinskaya, 2020; Prieto & Domínguez, 2020; Kim, Milliman & Lucas, 2020; Lord, 2020; Anand & Vohra, 2020; Činčalová, 2020; Jahangiri et al., 2020; Smalley, 2018; Albinsson & Arnesson, 2018; Darko-Asumadu, Sika-Bright & Osei-Tutu, 2018; Noronha & Magala, 2017; Yepes-Baldó et al., 2017; Banik, 2016; Jervis-Tracey et al., 2016; Tanwar & Prasad, 2016; Sommerlad, 2016; Gervais, 2016; Ibrahim et al., 2016; Silva et al., 2015; Boria-Reverter et al., 2015; Celma, Martínez-Garcia & Coenders, 2014; Ruivo & Neto, 2010; Closon, 2009; Linne, 2004; Bennett, 1976. |

| Work and living space | 80 | Riforgiate & Kramer, 2021; Beech, Sutton & Cheatham, 2021; Sorribes, Celma & Martínez-Garcia, 2021; Donoso, Valderrama & LaBrenz, 2021; Więcek-Janka & Jaźwińska, 2021; Sperling, 2021; Lafferty et al., 2021; Sellmaier & Buckingham, 2021; Höltge et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2020; Cisternas & Navia, 2020; Yerkes, Hoogenboom & Javornik, 2020; Jang & Ardichvili, 2020; Asante et al., 2020; Ghashghaeizadeh, 2020; Baral, 2020; Duffy, 2020; G-lvez, Tirado & Mart-nez, 2020; Mehta et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Peikert et al., 2020; Akter, Ali & Chang, 2020; Chikapa, 2020; Guillén, 2020; Kumari, 2019; Darrough, Kim & Zur, 2019; Dutta, 2019; John Britto & Magesh, 2019; Kim & Nam, 2019; Tomaselli, 2019; Sudarshan, Chockalingam & Velmurugan, 2019; Nevins & Hamouda, 2019; Short et al., 2019; Wardani & Anwar, 2019; Rezaee et al., 2019; Kobayashi, Eweje & Tappin, 2018; Ferri, Pedrini & Riva, 2018; Sherwood, Kelly & Bugallo, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Amutha, 2018; Bernstein & Valentini, 2017; Mehta & Leng, 2017; Subramaniam, Ibrahim & Maniam, 2017; Menna & Lago, 2017; [No author name available 3], 2017; García & Cosimi, 2017; Sar et al., 2017; Sasmoko, et al., 2017; Fernandes et al., 2017; Ciarini, 2016; Medrado & Jackson, 2016; Saltmarsh, 2016; Annink, Den Dulk & Amorós, 2016; Ellmer, dos Santos & Batiz, 2016; Kim & Windsor, 2015; Senasu & Virakul, 2015; Makhbul & Sheikh Khairuddin, 2014; Poerio, 2013; Bonab, Ebrahimpour & Ghorbani, 2013; Tarver, 2013; Stewart, 2013; AlSharif, Kruger & Tennant, 2012; Lai-Ching & Kam-Wah, 2012; Arney & Weitz, 2012; McCrea, Boreham & Ferguson, 2011; [No author name available 6], 2011; Solomon, 2011; Jang, Park & Zippay, 2011; Al-Bdour, Nasruddin & Lin, 2010; Buys & Terblenche, 2009; Roth & Moore, 2009; Bull, 2009; Schwanen & de Jong, 2008; Root & Wooten, 2008; Parkes & Langford, 2008; Dean, 2007; Pryjmachuk & Richards, 2007; Vuontisjärvi, 2006; Baldock & Hadlow, 2004; Taylor-Gooby, 2004. |

| Fair and adequate compensation | 19 | Cooke, Schuler & Varma, 2020; Hoang, Vu & Ngo, 2020; Midttun & Witoszek, 2020; Patti, Lobo & Fisichella, 2020; Rebelo, Simões & Salavisa, 2020; Pérez & Cifre, 2020; Sheehan et al., 2019; Mota-Santos et al., 2019; Verma, Mohammed & Bhargava, 2018; Flammer & Luo, 2017; Minz & Munda, 2016; Bhatnagar, 2014; Clouston, 2014; Herbert et al., 2014; Burnett., Swan & Cooper, 2013; Teti & Andriotto, 2013; Pocock, Charlesworth & Chapman, 2013; Rizza & Sansavini, 2013; Pichler, 2009. |

| Career opportunity | 40 | [No author name available 5], 2020; Nath & Dwivedi, 2020; Adriano & Callaghan, 2020; Tarigan et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2020; Enestvedt et al., 2020; Self, Gordon & Jolly, 2019; Hallward & Bekdash-Muellers, 2019; Anto Juliet Mary et al., 2019; Abidin et al., 2019; Welford & O’Brien, 2019; Wang & Chen, 2019; Kumari & Saini, 2018; Rijal & Wasti, 2018; Lindemann, 2018; Vampo, 2018; Lämsä et al., 2017; Smidt, Pétursdóttir & Einarsdóttir, 2017; Swanberg et al., 2017; Kato & Kodama, 2017; [No author name available 2], 2017; Tanwar & Prasad, 2017; Mutovkina, Finckh e Gall, 2016; Van Loggerenberg & Nienaber, 2015; Tanaka, 2015; Finkelstein, 2014; Tremblay, 2013; Ng & Gossett, 2013; Schueller-Weidekamm & Kautzky-Willer, 2012; Af Hällström, 2012; Rehman & Roomi, 2012; Håpnes & Rasmussen, 2011; Hennessy, 2009; Buddhapriya, 2009; Waumsley & Houston, 2009; Barclay, 2008; Casper, Weltman & Kwesiga, 2007; Halfer & Graf, 2006; McDowell et al., 2005; Zimmerman et al., 2003. |

| Social relevance of work | 40 | Pothuraju & Alekhya, 2020; Šperková & Skýpalová, 2020; Ribers, 2020; Eisapareh et al., 2020; Zhang & Liu, 2019; Horiuchi, 2019; Shahid & Hamid, 2019; Amor-Esteban et al., 2019; Bennett & Waterhouse, 2018; Papasolomou et al., 2018; Kagnicioglu, 2017; Bloom, 2017; Thang & Fassin, 2017; Meil Landwerlin, 2017; Megías, 2017; Umans et al., 2016; Rodell et al., 2016; Dauphin, 2015; Menlo, 2015; Arndt, Singhapakdi & Tam, 2015; Tongo, 2015; Timossi et al., 2015; Mills et al., 2014; Karataş-Özkan et al., 2014; Domínguez, 2014; Asomba et al., 2013; Smith & Dougherty, 2012; Onat & Beji, 2012; Noali, 2012; Brick, 2011; Khan & Afzal, 2011; Westring & Ryan, 2010; Malik et al., 2010; Jang, 2009; Royuela, López-Tamayo & Suriñach, 2009; Marcinkus, Gordon & Whelan-Berry, 2007; Mohan & Kumar, 2006; Williams & Cooper, 2004; Rachor, 1998; Crouter & Garbarino, 1982. |

References

- Keeney, J.; Boyd, E.M.; Sinha, R.; Westring, A.F.; Ryan, A.M. From “work-family” to “work-life”: Broadening our conceptualization and measurement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 82, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, K. A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 67, 169–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Zivnuska, S. Is work-family balance more than conflict and enrichment? Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 1459–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of Conflict Between Work and Family Roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When Work and family are Allies: A Theory of Work-Family Enrichement. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 3, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.S.; Kotrba, L.M.; Mitchelson, J.K.; Clark, M.A.; Baltes, B.B. Antecedents of work-family conflict: A meta-analytic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 689–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.S.; Gonçalves, E.; Costa, D. Conflito Trabalho-Família: Contributos para a sua caracterização e gestão. Rev. E-Psi 2020, 9, 56–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Moeckel, R.; Moreno, A.T.; Shuai, B.; Gao, J. A work-life conflict perspective on telework. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 141, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotheridge, C.M.; Lee, R.T. Impact of work-family interference on general well-being: A replication and extension. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voydanoff, P.; Donnelly, B.W. Incorporating community into work and family research: A review of basic relationships. Hum. Relat. 2001, 54, 1609–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R.C.; Hyde, J.S. Women, man, work and family. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buffardi, L.C.; Smith, J.I.; O’brien, A.S.; Erdwins, C.J. The impact of dependent care responsability and gender on work attitudes. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1999, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frone, M.R. Work-family balance. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology; Quick, J., Tetrick, L., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Gajendran, R.S.; Harrison, D.A. The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown About Telecommuting: Meta-Analysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jostell, D.; Hemlin, S. After hours teleworking and boundary management: Effects on work-family conflict. Work 2018, 60, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A Meta-Analysis of Work-Family Conflict and Various Outcomes with a Special Emphasis on Cross-Domain Versus Matching-Domain Relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, L.B.; Sanchez, D.L. Quality of work-life. In Encyclopedia of Industrial/Organizational Psychology; Rogelberg, S.G., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 651–652. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, R.E. Quality of Work Life: What is it? Camb. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1973, 15, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, A.P. Corporate Social Responsibility from an Employees’ Perspective: Contributes for Understanding Job Attitudes. Ph.D. Thesis, ISCTE-IUL, Lisboa, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Comissão das Comunidades Europeias. Livro Verde: Promover um Quadro Europeu Para a Responsabilidade Social das Empresas; CCE: Bruxelas, Belgium, 2001; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/committees/empl/20020416/doc05a_pt.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Comissão das Comunidades Europeias. Responsabilidade Social das Empresas: Um Contributo Para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável; CCE: Bruxelas, Belgium, 2002; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/committees/empl/20021111/com(2002)347_PT.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Garfield, E. Use of Journal Citation Reports and Journal Performance Indicators in measuring short and long-term journal impact. Croat. Med. J. 2000, 41, 368–374. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, G.L.; Gonzalez, C.N.B.; Veloso, F. Using co-authorship and citation analysis to identify research groups: A new way to assess performance. Scientometrics 2016, 108, 1171–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, G. The meaning and measure of revisited moral competence: A model of the double aspect of moral competence. Crit. Reflex. Psychol. 2000, 13, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. Social Network Analysis: A Handbook, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications, 19th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, T.; Kodama, N. The effect of corporate social responsibility on gender diversity in the workplace: Econometric evidence from Japan. Br. J. Ind. Rel. 2018, 56, 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcel, T.L. Work and family in the 21st century. Work Occup. 1999, 26, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carponi, P.J. Work/life balance: You can’t get there from here. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1997, 33, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Haddock, S.A.; Zimmerman, T.S.; Ziembra, S.J. Ten adaptive strategies for family and work balance: Advice from successful families. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2001, 27, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiecolt, K.J. Satisfation with work and family life: No evidence of a cultural reversal. J. Marriage Fam. 2003, 65, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, C.; Tham, T.L.; Holland, P.; Cooper, B. Psychological contract fulfilment, engagement and nurse professional turnover intention. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 40, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riforgiate, S.E.; Kramer, M.W. The nonprofit assimilation process and work-life balance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorribes, J.; Celma, D.; Martínez-Garcia, E. Sustainable human resources management in crisis contexts: Interaction of socially responsible labour practices for the wellbeing of employees. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 936–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Więcek-Janka, E.; Jaźwińska, D. Quality of life, sustainable development and social responsibility of business in the qualitological aspect. In Social Responsibility and Corporate Governance; Mulej, M., O’Sullivan, G., Štrukelj, T., Eds.; Palgrave Studies in Governance, Leadership and Responsibility; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 143–167, CORRETO. [Google Scholar]

- Sellmaier, C.; Buckingham, S.R. ‘I think sometimes that dads are kind of forgotten (…) so it’s nice that we also get a voice’: Work-life experiences of employed U.S. fathers caring for a child with special health care needs. Community Work Fam. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peikert, M.L.; Inhestern, L.; Krauth, K.A.; Escherich, G.; Rutkowski, S.; Kandels, D.; Bergelt, C. Returning to daily life: A qualitative interview study on parents of childhood cancer survivors in Germany. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.D.; Miller, J.; Vitous, C.A.; Krenz, C.; Brady, K.T.; Brown, A.J.; Jagsi, R. From stigma to validation: A qualitative assessment of a novel national program to improve retention of physician-scientists with caregiving responsibilities. J. Women’s Health 2020, 29, 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höltge, J.; Theron, L.; Jefferies, P.; Ungar, M. Family resilience in a resource-cursed community dependent on the oil and gas industry. Fam. Process 2021, 60, 1453–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonelli, M.J.; Alcadipani, R. The work of managers. The change that did not occur. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 10, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Cisternas, C.F.; Navia, A.C. Time in work-life conflict: The case of academic women in managerial universities. Psicoperspectivas 2020, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Darko-Asumadu, D.A.; Sika-Bright, S.; Osei-Tutu, B. The influence of work-life balance on employees’ commitment among bankers in Accra, Ghana. Afr. J. Soc. Work. 2018, 8, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yerkes, M.A.; Hoogenboom, M.; Javornik, J. Where’s the community in community, work and family? A community-based capabilities approach. Community Work Fam. 2020, 23, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Ardichvili, A. The role of HRD in CSR and sustainability: A content analysis of corporate responsibility reports. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 44, 549–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, C.M.; Arnett, J.J.; Palmer, C.G.; Nelson, L.J. Established adulthood: A new conception of ages 30 to 45. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante Boadi, E.; He, Z.; Bosompem, J.; Opata, C.N.; Boadi, E.K. Employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its effects on internal outcomes. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 611–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghashghaeizadeh, N. Designing and development model for improving the quality of work life of faculty members. Iran Occup. Health 2020, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Baral, R. Comparing the situation and person-based predictors of work–family conflict among married working professionals in India. Equal. Divers. Incl. 2020, 39, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A. Identities, academic cultures, and relationship intersections: Postsecondary dance educators’ lived experiences pursuing tenure. Res. Dance Educ. 2020, 21, 188–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, A.; Tirado, F.; Martínez, M.J. Work-life balance, organizations and social sustainability: Analyzing female telework in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Rhou, Y.; Topcuoglu, E.; Gug Kim, Y. Why hotel employees care about corporate social responsibility (CSR): Using need satisfaction theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, K.; Ali, M.; Chang, A. Work–life programmes and organisational outcomes: The role of the human resource system. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 516–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, H.J.; Kirch, D.G.; Nasca, T.J.; Katsufrakis, P.J.; McMahon, G.T.; Shannon, S.C.; Ciccone, A.L. Navigating tumultuous change in the medical profession: The coalition for physician accountability. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, G.S. Managing work-family boundary-the link between work-life benefits and organizational citizenship. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 28, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaee, R.; Shoaahaghighi, P.; Bordbar, N.; Tavani, K.; Ravangard, R. Factors affecting the family physicians’ intention to leave the job: A case of Iran. Open Public Health J. 2019, 12, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, G.; Arnesson, K. The managerial position in a Swedish municipal organization: Possibilities and limitations. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2018, 39, 500–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrough, M.; Kim, H.; Zur, E. The impact of corporate welfare policy on firm-level productivity: Evidence from unemployment insurance. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 795–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaselli, G. Corporate family responsibility as a driver for entrepreneurial success. In Responsible People; Farache, F., Grigore, G., Stancu, A., McQueen, D., Eds.; Palgrave Studies in Governance, Leadership and Responsibility; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Short, B.; Lambeth, L.; David, M.; Ryall, M.; Hood, C.; Pahalawatta, U.; Dawson, A. An immersive orientation programme to improve medical student integration and well-being. Clin. Teach. 2019, 16, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, D.; Sabariah, K.Y.; Yussof, K.M.; Sarjono, F.; Tibok, R.P. An exploratory analysis of the life-cycle influence on lecturers’ management of work and life. Int. Bus. Manag. 2016, 10, 3290–3294. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, K.; Eweje, G.; Tappin, D. Employee wellbeing and human sustainability: Perspectives of managers in large Japanese corporations. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, L.M.; Pedrini, M.; Riva, E. The impact of different supports on work-family conflict. Empl. Relat. 2018, 40, 903–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.W.; Suh, C.; Lee, C.K.; Son, B.C. The work-life balance and psychosocial well-being of south Korean workers. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 30, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amutha, R. Work life balance among IT industry-an empirical study. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2018, 9, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, P.O.; Cosimi, L. Part-time work of women in Spain and Italy: The weakening of the rule of stable employment. Rev. Del Minist. Empl. Segur. Soc. MEYSS 2017, 131, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Arney, J.; Weitz, R. Gendering affective disorders in direct-to-consumer advertisements. Res. Sociol. Health Care 2012, 30, 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Marcinkus, W.C.; Gordon, J.R.; Whelan-Berry, K.S. The relationship of social support to the work-family balance and work outcomes of midlife women. Women Manag. Rev. 2007, 22, 86–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sar, S.; Mohanty, A.K.; Kar, S.K.; Dash, M. The impact of formal and informal organizational support on work life spillover: A study of IT sector. Int. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. Res. 2017, 15, 375–387. [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar, K.; Prasad, A. Employer brand scale development and validation: A second-order factor approach. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.B.; Martins, B.S.; Caixeta, R.P.; Da Costa Filho, C.G.; Braga, G.A.; Antonialli, L.M. Quality of work life: An evaluation of Walton model with analysis of structural equations. Espacios 2017, 38, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Straub, C.; Kusyk, S. Making a life or making a living? Cross-cultural comparisons of business students’ work and life values in Canada and France. Cross Cult. Manag. 2007, 14, 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrado, L.; Jackson, L.A. Corporate nonfinancial disclosures: An illuminating look at the corporate social responsibility and sustainability reporting practices of hospitality and tourism firms. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 16, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhapakdi, A.; Lee, D.; Sirgy, M.J.; Senasu, K. The impact of incongruity between an organization’s CSR orientation and its employees’ CSR orientation on employees’ quality of work life. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senasu, K.; Virakul, B. The effects of perceived CSR and implemented CSR on job-related outcomes: An HR perspective. J. East-West Bus. 2015, 21, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, A.D.; Singhapakdi, A.; Tam, V. Consumers as employees: The impact of social responsibility on quality of work life among Australian engineers. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.L.M.; Dougherty, D.S. Revealing a master narrative: Discourses of retirement throughout the working life cycle. Manag. Commun. Q. 2012, 26, 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonab, M.B.; Ebrahimpour, D.; Ghorbani, A. Quality of work life and family functioning in faculty members of Islamic Azad university. Life Sci. J. 2013, 10 (Suppl. S2), 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Eikeland, T.B. Emergent trust and work life relationships: How to approach the relational moment of trust. Nord. J. Work. Life Stud. 2015, 5, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellmer, A.; dos Santos, A.J.; Batiz, E.C. Analysis of the quality of life and quality of life at work between teachers, aiming at personal and professional satisfaction. Espacios 2016, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Annink, A.; Den Dulk, L.; Amorós, J. Different strokes for different folks? the impact of heterogeneity in work characteristics and country contexts on work-life balance among the self-employed. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2016, 22, 880–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, L.M. Family care responsibilities and employment: Exploring the impact of type of family care on work-family and family-work conflict. J. Fam. Issues 2013, 34, 113–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Still, M.C. Family responsibilities discrimination and the new institutionalism: The interactive process through which legal and social factors produce institutional change. Hastings Law J. 2008, 59, 1491–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Dauphin, S. The familialism of the French family policy: Social order and gendered order. An. Univ. Bucur. Stiinte Politice 2015, 17, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Windsor, C. Resilience and work-life balance in first-line nurse manager. Asian Nurs. Res. 2015, 9, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timossi, L.S.; Moreira, M.B.; Krinski, K.; dos Santos Junior, G.; de Francisco, A.C. Effect and relationship between quality of life and quality of life in the work through the use of the multivaried analysis. Espacios 2015, 36, 7. [Google Scholar]

- McCrea, R.; Boreham, P.; Ferguson, M. Reducing work-to-life interference in the public service: The importance of participative management as mediated by other work attributes. J. Sociol. 2011, 47, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.J.; Park, R.; Zippay, A. The interaction effects of scheduling control and work-life balance programs on job satisfaction and mental health. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2011, 20, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Gooby, P. New social risks in postindustrial society: Some evidence on responses to active labour market policies from Eurobarometer. Int. Soc. Secur. Rev. 2004, 57, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, H. Tipping the balance: The problematic nature of work-life balance in a low-income neighborhood. J. Soc. Policy 2007, 36, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Morgan, G.; Smircich, L. The case for qualitative research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1980, 5, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Strobino, M.R.; Teixeira, R.M. Empreendedorismo feminino e o conflito trabalho- família: Estudo de multicasos no setor de comércio de material de construção da cidade de Curitiba. Rev. Adm. 2014, 49, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.B.; Rossetto, C.R. Os conflitos entre a prática gerencial e as relações em família: Uma abordagem complexa e multidimensional. Rev. Adm. Contemp. 2010, 14, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Beech, H.H.; Sutton, A.; Cheatham, L. Parenting, privilege, and pandemic: From surviving to thriving as a mother in the academy. Qual. Soc. Work 2021, 20, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafferty, A.; Phillips, D.; Dowling-Hetherington, L.; Fahy, M.; Moloney, B.; Duffy, C.; Kroll, T. Colliding worlds: Family carers’ experiences of balancing work and care in Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.D.; Greenhaus, J.H. Work and Family—Allies or Enemies? What Happens When Business Professionals Confront Life Choices; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz, J.G. Work-family spillover and health during midlife: Is managing conflict everything? Am. J. Health Promot. 2000, 14, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruderman, M.N.; Ohlott, J.P.; Panzer, K.; King, S.N. Benefits of multiple roles for managerial women. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Wayne, J.; Musisca, N.; Fleeson, W. Considering the role of personality in the work-family experience: Relationships of the Big Five to work-family conflict and facilitation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 108–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shein, J.; Chen, C.P. Work-Family Enrichment: A Research of Positive Transfer; Sense Publishers: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Source Title | Publications | Impact Factor |

|---|---|---|

| International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management | 3 | 5.66 |

| Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | 4 | 4.54 |

| Journal Of Business Ethics | 4 | 4.14 |

| International Journal of Human Resource Management | 5 | 3.04 |

| Sustainability Switzerland | 4 | 2.57 |

| BMJ Open | 3 | 2.49 |

| Employee Relations | 3 | 2.31 |

| Community Work and Family | 5 | 1.47 |

| Gender Place and Culture | 4 | 1.18 |

| Gender In Management | 4 | 1.05 |

| Human Resource Management International Digest | 4 | 0.31 |

| Author | Affiliation | Location | Last Article * | No. of Citations * | Main Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halfer D. | Children’s Memorial Hospital | USA | 2006 | 159 | Responsibility, work-life |

| Vuontisjärvi T. | (n.a.) | Finland | 2006 | 125 | European union; Finland; HR reporting; Human resource management; Social reporting |

| Flammer C. | Boston University | USA | 2017 | 110 | Adverse behavior; corporate social responsibility; employee engagement; employee governance; unemployment insurance |

| McDowell L. | University of Oxford | England | 2005 | 97 | Childcare; Gendered moral rationalities; Narratives of care; Work-life balance |

| Rehman S. | Superior University | Pakistan | 2012 | 93 | Cultural norms; Gender; Islamic society; Pakistan; Social values; Women entrepreneurs; Work-life balance |

| Casper W.J. | University of Texas at Arlington | USA | 2007 | 89 | Equity theory; Fairness; Family-friendly; Singles; Work-family; Work-life |

| Strand R. | (n.a.) | USA | 1983 | 84 | (n.a.) |

| Cooke F.L. | Monash University | Australia | 2018 | 80 | Asia; context; corporate social responsibility; international HRM; multinational company; work-life balance |

| Parkes L.P. | Macquarie University | Australia | 2008 | 76 | Employee engagement; Organizational climate; Retention; Social responsibility; Work-life balance |

| Armstrong D.J. | University of Arkansas | USA | 2007 | 76 | Causal mapping; Cognition; Gender and information technology; Glass ceiling; Turnover; Work-family conflict |

| Institution | Location | Main Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| University of Michigan | USA | Corporate social responsibility; Ethical leadership; Pro-environmental behavior; Quality of work-life; Values |

| University of Colorado | USA | COVID-19 pandemic; domestic and academic responsibilities; female academics; gender roles |

| Washington University School of Medicine | USA | Corporate social responsibility; employee corporate identification; employee performance; employee quality of work life; employee work motivation |

| University of North Carolina School of Medicine | USA | Corporate Social Responsibility; IT sector; Organization Performance; Quality of work-life |

| Medical University of South Carolin | USA | Organizational role; Work-family conflict |

| University of California | USA | Careers; Family life; Gender; Leadership; Oman; Success |

| University of Michigan | USA | Family work conflict; Migrant academics; Migration; Work life conflict; Work life integration |

| Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine | USA | Corporate social responsibility; Employees; Work-family conflict |

| Yale School of Medicine | USA | Capabilities; corporate social responsibility; Expatriation; family; international assignment; stakeholder; well-being; work-life relationship |

| Medical College of Wisconsin | USA | Crisis; Employment; Gender; Part time |

| Cluster Number | Colour | Cluster Name * | Locations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red | India | Austria, India, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden |

| 2 | Green | United States | Australia, Germany, South Korea, Switzerland, United States |

| 3 | Dark blue | United Kingdom | China, Ghana, Pakistan, United Kingdom |

| 4 | Yellow | Japan | Finland, France, Japan |

| 5 | Purple | Malaysia | Belgium, Malaysia, Vietnam |

| 6 | Light blue | Spain | Ireland, Portugal, Spain |

| 7 | Orange | Italy | Brazil, Italy, Turkey |

| 8 | Brown | Canada | Canada, South Africa |

| Cluster Number * | Colour | Cluster Name ** | Main Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red | Policy | Family life, gender diversity, human resource management, job satisfaction, leadership, policy, work-family balance |

| 2 | Green | Burnout | Burnout, family policy, organizational culture, stress, well-being, work and family |

| 3 | Dark blue | Corporate social responsibility | Corporate social responsibility, employee engagement, employees, millennials, work-family conflict |

| 4 | Yellow | Work-life balance | COVID-19, employment, paternity leave, women empowerment, work-life balance |

| 5 | Purple | Family | Family, gender equality, responsibility, women, work-life balance |

| 6 | Light blue | Quality of work-life | Organizational commitment, quality of work-life, social support, work-life conflict |

| 7 | Orange | Sustainability | Management, sustainability, sustainable development |

| 8 | Brown | Work | Social policy, work, young workers |

| Dimensions | QWL Sub Dimensions | No. of Articles | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social integration in work organization | Social support | 51 | 15.2 |

| Absence of prejudice | |||

| Conditions for interpersonal openness | |||

| Social mobility facilities | |||

| Egalitarianism | |||

| Opportunity to use and develop human capacities | Autonomy | 29 | 8.71 |

| Executing Complete Tasks | |||

| Work planning | |||

| Quality and quantity of information | |||

| Multiple use of skill | |||

| Safe and healthy working conditions | Physical conditions | 42 | 12.61 |

| Schedule | |||

| Age limits for employment | |||

| Constitutionalism in work | Equal treatment | 32 | 9.61 |

| Free expression | |||

| Possibility of appeal | |||

| Privacy | |||

| Work and total life space | 80 | 24.02 | |

| Time with family | |||

| Overtime hours | |||

| Adequate and fair compensation | Adequate | 19 | 5.71 |

| Fair | |||

| Career opportunitties | Stability in employment or income | 40 | 12.01 |

| Incentives/investments in courses | |||

| Opportunity to continue studies | |||

| Opportunity to expand work | |||

| Social relevance of work-life | Social relevance of work | 40 | 12.01 |

| Dimension | Quant. of Articles | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|

| Work and living space | 80 | Riforgiate & Kramer, 2021; Beech, Sutton & Cheatham, 2021; Sorribes, Celma & Martínez-Garcia, 2021; Donoso, Valderrama & LaBrenz, 2021; Więcek-Janka & Jaźwińska, 2021; Sperling, 2021; Lafferty et al., 2021; Sellmaier & Buckingham, 2021; Höltge et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2020; Cisternas & Navia, 2020; Yerkes, Hoogenboom & Javornik, 2020; Jang & Ardichvili, 2020; Asante et al., 2020; Ghashghaeizadeh, 2020; Baral, 2020; Duffy, 2020; G-lvez, Tirado & Mart-nez, 2020; Mehta et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Peikert et al., 2020; Akter, Ali & Chang, 2020; Chikapa, 2020; Guillén, 2020; Kumari, 2019; Darrough, Kim & Zur, 2019; Dutta, 2019; John Britto & Magesh, 2019; Kim & Nam, 2019; Tomaselli, 2019; Sudarshan, Chockalingam & Velmurugan, 2019; Nevins & Hamouda, 2019; Short et al., 2019; Wardani & Anwar, 2019; Rezaee et al., 2019; Kobayashi, Eweje & Tappin, 2018; Ferri, Pedrini & Riva, 2018; Sherwood, Kelly & Bugallo, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Amutha, 2018; Bernstein & Valentini, 2017; Mehta & Leng, 2017; Subramaniam, Ibrahim & Maniam, 2017; Menna & Lago, 2017; [No author name available 3], 2017; García & Cosimi, 2017; Sar et al., 2017; Sasmoko, et al., 2017; Fernandes et al., 2017; Ciarini, 2016; Medrado & Jackson, 2016; Saltmarsh, 2016; Annink, Den Dulk & Amorós, 2016; Ellmer, dos Santos & Batiz, 2016; Kim & Windsor, 2015; Senasu & Virakul, 2015; Makhbul & Sheikh Khairuddin, 2014; Poerio, 2013; Bonab, Ebrahimpour & Ghorbani, 2013; Tarver, 2013; Stewart, 2013; AlSharif, Kruger & Tennant, 2012; Lai-Ching & Kam-Wah, 2012; Arney & Weitz, 2012; McCrea, Boreham & Ferguson, 2011; [No author name available 6], 2011; Solomon, 2011; Jang, Park & Zippay, 2011; Al-Bdour, Nasruddin & Lin, 2010; Buys & Terblenche, 2009; Roth & Moore, 2009; Bull, 2009; Schwanen & de Jong, 2008; Root & Wooten, 2008; Parkes & Langford, 2008; Dean, 2007; Pryjmachuk & Richards, 2007; Vuontisjärvi, 2006; Baldock & Hadlow, 2004; Taylor-Gooby, 2004. |

| Authors (Year) | Work-Life Relations and the Context of Social Responsibility and Sustainability |

|---|---|

| Kato & Kodama, 1999; Dauphin, 2015; Kim, M.; Windsor, 2015; Timossi et al., 2015 | It values team performance, pleasant work environments with a predominance of open communications to match the work-family needs of employees, combined with personal resilience. |

| Carponi, 1997; Parcel, 1999; Haddock, Zimmerman & Ziembra, 2001; Smith & Dougherty, 2012; Bonab et al., 2013; Eikeland, 2015; Ellmer et al., 2016; Kiecolt, 2019; Sheehan et al., 2019 | Studies the relationship between personal life and work life. Time allocation for each institution and the strategies families employ to fulfill their obligations at work and at home. |

| Singhapakdi et al., 2015; Arndt et al., 2015; Senasu & Virakul, 2015; Riforgiate & Kramer, 2021 | Checks employee retention, compensation and commitment to the organization and the balance with personal life. |

| Morgan & Smircich, 1980; Taylor-Gooby, 2004; Dean, 2007; Sar et al., 2017; Tanwar & Prasad, 2017; Darko-Asumadu et al., 2018; Yerkes et al., 2020; Jang & Ardichvili, 2020; Mehta et al., 2020; Sorribes, Celma & Martínez-Garcia, 2021 | Analyzes the effects of the interaction between different work practices of socially responsible human resource management on employee well-being variables (job satisfaction, work stress, and trust in management) as a way to reduce absenteeism, low turnover rates, and increase productivity. |

| Medrado & Jackson, 2016; Więcek-Janka & Jaźwińska, 2021 | It presents, based on the analysis of sustainable development indicators, aspects of the quality of life to be complemented with new indicators related to the well-being of the human somatic sphere. |

| Marcinkus et al., 2007; Arney & Weitz, 2012; García & Cosimi, 2017; Peikert et al., 2020; Sellmaier & Buckingham, 2021 | Strategic decision-making in job selection by workers; flex-time employment. |

| Ibrahim et al., 2016; Albinsson & Arnesson, 2018; Chaudhry et al., 2019; Darrough, Kim, & Zur, 2019; Rezaei et al., 2019; Short et al., 2019; Kumari 2019; Tomaselli, 2019; Jones et al., 2020; | Addresses the need for institutional leaders to implement programs and policies that can promote awareness and normalization of the challenges in the work-family relationship in the context of worker health. |

| Tonelli & Alcadipani, 2004; Zhanget al., 2007; Fernandes et al., 2017; Cisternas & Navia, 2020; Höltge et al., 2021 | Points out a never-ending cycle of work-life balance, hours worked and income instability, fair compensation throughout the economic cycle. |

| Asante et al., 2020; Ghashghaeizadeh, 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Akter, Ali & Chang, 2020 | Checks the relationship between employees’ perception of CSR and its effects on internal corporate outcomes. |

| Silva & Rossetto, 2010; Campos-Strobino & Teixeira, 2014; Amutha, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Baral, 2020; Duffy, 2020 | Examines the relative power of situational factors in organizations versus personal in predicting the work-family relationship. |

| Gálvez, Tirado & Martínez, 2020 | Analyzes telecommuting as a policy tool within organizations that drives or hinders the development of social sustainability. |

| Kobayashi et al., 2018; Ferri, Pedrini & Riva, 2018 | Analyzes meritocracy versus gender equality as a CSR strategy. |

| Still, 2008; Stewart, 2013; Annink et al., 2016 | Self-employment as a way to combine work and responsibilities in other areas of personal life. |

| McCrea et al., 2011; Jang et al., 2011 | Checks the reflexes of participative management between employees and organizations. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marôco, A.L.; Nogueira, F.; Gonçalves, S.P.; Marques, I.C.P. Work-Family Interface in the Context of Social Responsibility: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053091

Marôco AL, Nogueira F, Gonçalves SP, Marques ICP. Work-Family Interface in the Context of Social Responsibility: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053091

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarôco, Ana Lúcia, Fernanda Nogueira, Sónia P. Gonçalves, and Isabel C. P. Marques. 2022. "Work-Family Interface in the Context of Social Responsibility: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053091

APA StyleMarôco, A. L., Nogueira, F., Gonçalves, S. P., & Marques, I. C. P. (2022). Work-Family Interface in the Context of Social Responsibility: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 14(5), 3091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053091