Public Sector Downsizing and Public Sector Performance: Findings from a Content Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

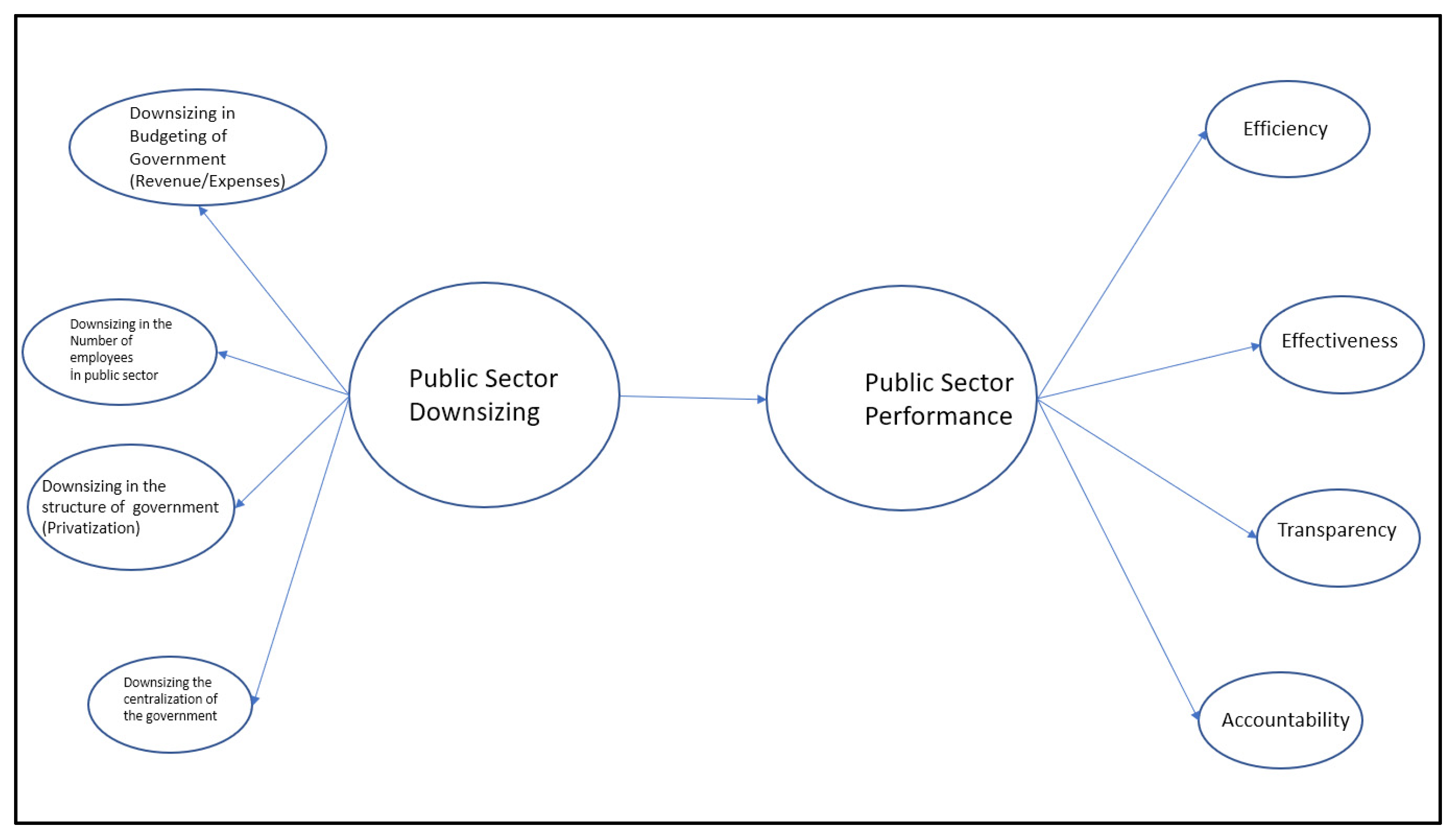

2.1. Public Sector Performance

2.1.1. Efficiency

2.1.2. Effectiveness

2.1.3. Transparency

2.1.4. Accountability

2.2. Public Sector Downsizing

2.2.1. Downsizing in the Budgeting of Government

2.2.2. Downsizing in the Number of Employees in the Public Sector

2.2.3. Downsizing in the Structure of Government (Privatization)

2.2.4. Downsizing in the Centralization of Government

2.2.5. Public Sector Downsizing and Public Sector Performance

3. Research Method

3.1. Data Collection and Analysis

3.2. Findings

3.2.1. Demographic Information

3.2.2. Findings for Effects of Downsizing on Public Sector Performance

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Longenecker, C.O.; Nykodym, N. Public Sector Performance Appraisal Effectiveness: A Case Study. Public Pers. Manag. 1996, 25, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcroft, A.; Willis, R. The (un)intended outcome of public sector performance measurement. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2005, 18, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. Performance indicators and outcome in the public sector. Public Money Manag. 1995, 15, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, D.; Hammerschmid, G.; Jilke, S.; van de Walle, S. The state and perceptions of public sector reform in Europe. In The International Handbook of Public Administration and Governance; Massey, A., Johnston, K., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Liu, B.; Saleem Butt, A. Predictors and outcomes of change recipient proactivity in public organizations of the Kurdistan region of Iraq. Int. Public Manag. J. 2020, 23, 823–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ann Feldheim, M. Public Sector Downsizing and Employee Trust. Int. J. Public Adm. 2007, 30, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, C.-J.; Tien, C.; Chi, Y.-C. Downsizing to the wrong size? A study of the impact of downsizing on firm performance during an economic downturn. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 1519–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalos, P.; Chen, C.J.P. Employee Downsizing Strategies: Market Reaction and Post Announcement Financial Performance. J. Bus. Finance Account. 2002, 29, 847–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Bullon, F.; Sanchez-Bueno, M.J. Downsizing implementation and financial performance. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.M. The politics and consequences of performance measurement. Policy Soc. 2015, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, R.; Tommasino, P. Public-sector efficiency and political culture. FinanzArchiv/Public Financ. Anal. 2013, 69, 289–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunse, K.; Vodicka, M.; Schönsleben, P.; Brülhart, M.; Ernst, F.O. Integrating energy efficiency performance in production management—Gap analysis between industrial needs and scientific literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 19, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Gulati, R. Measuring efficiency, effectiveness, and performance of Indian public sector banks. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2009, 59, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Walle, S. Comparing the performance of national public sectors: Conceptual problems. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2008, 57, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimba, S.H.N.P.; Helden, J.G.; Tillema, S. Public sector performance measurement in developing countries A literature review and research agenda. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2007, 3, 192–208. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Cheng, Z. The role of change content, context, process, and leadership in understanding employees’ commitment to change. Public Pers. Manag. 2018, 47, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. Performance Measurement and Management in the Public Sector: Some Lessons from Research Evidence. Public Admin. Dev. 2015, 35, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.C. Making performance measurement systems more effective in public sector organizations. Meas. Bus. Excel. 2012, 16, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H. Performance Management; Pearson/Prentice HallUpper: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Afonso, A.; Schuknecht, L.; Tanzi, V. Public sector efficiency: An international comparison. Public Choice 2005, 123, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalayini, A.M.; Noble, J.S. The changing basis of performance measurement. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1996, 16, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curristine, T.; Lonti, Z.; Joumard, I. Improving public sector efficiency: Challenges and opportunities. OECD J. Budg. 2007, 7, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goesaert, T.; Heinz, M.; Vanormelingen, S. Downsizing and firm performance: Evidence from German firm data. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2015, 24, 1443–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, C.J. Outcomes-Based Performance Management in the Public Sector: Implications for Government Accountability and Effectiveness. Public Adm. Rev. 2002, 62, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhigbe, A.; McNulty, J.E.; Stevenson, B.A. Additional evidence on transparency and bank financial performance. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2017, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terence, R. Mitchell, Motivation: New Directions for Theory, Research, and Practice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Mihaiu, D.M.; Opreana, A.; Cristescu, M.P. Efficiency, effectiveness, and performance of the public sector. Rom. J. Econ. Forecast. 2010, 4, 132–147. [Google Scholar]

- Afonso, A.; Schuknecht, L.; Tanzi, V. Public sector efficiency: Evidence for new EU member states and emerging markets. Appl. Econ. 2010, 42, 2147–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Mayston, D. Measuring efficiency in the public sector. Omega 1987, 15, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Colclough, C. Improving the Efficiency of Public Sector Health Services in Developing Countries: Bureaucratic Versus Market Approaches. Health Economic & Financial Programm. 1995. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.971.3327&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Borge, L.-E.; Falch, T.; Tovmo, P. Public sector efficiency: The roles of political and budgetary institutions, fiscal capacity, and democratic participation. Public Choice 2008, 136, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, I. Evaluation, learning, and the effectiveness of public services: Towards a quality of public service model. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 1996, 9, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, A.; Baird, K.; Schoch, H.P. Factors influencing the effectiveness of performance measurement systems. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2011, 31, 1287–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Hsieh, J.Y. Managerial Effectiveness of Government Performance Measurement: Testing a Middle-Range Model. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, C. What is transparency? Public Integr. 2009, 11, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, D. Why is transparency about public expenditure so elusive? Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2012, 78, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasavage, D. Transparency, Democratic Accountability, and the Economic Consequences of Monetary Institutions. Am. J. Political Sci. 2003, 47, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucoin, P.; Heintzman, R. The Dialectics of Accountability for Performance in Public Management Reform. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2000, 66, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lancer Julnes, P. Performance measurement: An effective tool for government accountability? The debate goes on. Evaluation 2006, 12, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollanen, R.M. Annual Performance Reporting as Accountability Mechanism in Local Government. Int. J. Bus. Public Adm. 2014, 11, 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, J.; Bakar, A.A. The practice of corporate downsizing during economic downturn among selected companies in Malaysia. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2003, 8, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, S.H.; Everard, A.; Hung, L.T.S. Strategic downsizing: Critical success factors. Manag. Decis. 1999, 37, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmann, T.; Brazas, M. Downsizing. Eur. Manag. J. 1993, 11, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, H. Job insecurity and psychological well-being: Review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahtera, J.; Kivimaki, M.; Pentti, J. Effect of organisational downsizing on health of employees. Lancet 1997, 350, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.J.; Cameron, K.S. Organizational downsizing: A convergence and reorientation framework. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labib, N.; Appelbaum, S.H. The Impact of Downsizing Practices on Corporate Success. J. Manag. Dev. 1994, 13, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.S. Strategies for successful organizational downsizing. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1994, 33, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblet, A.; Teo, S.T.T.; McWilliams, J.; Rodwell, J.J. Which work characteristics predict employee outcomes for the public-sector employee? An examination of generic and occupation-specific characteristics. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 16, 1415–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Revising Perry’s Measurement Scale of Public Service Motivation. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2009, 39, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, G.A.; Selden, S.C.; Ii, R.L.F. Individual Conceptions of Public Service Motivation. Public Adm. Rev. 2000, 60, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, T.; Schott, C. Public sector employees in a challenging work environment. Public Adm. 2019, 97, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, S.T.T. Effectiveness of a corporate H.R. department in an Australian public-sector entity during commercialization and corporati-zation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2002, 13, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.; Forbis, R.; Golden, A.; Nelson, S.; Robinson, J. On the Ethics of At-Will Employment in the Public Sector. Public Integr. 2006, 8, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, M. Efficient Public Sector Downsizing. In The Paper Prepared for Research Project on Public Sector Retrenchment and Efficient Compensation Schemes; Rama Martin. World Bank, Research Committee: Washington, WA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cote, N.P.; Bruce, R.R. Downsizing with competitive outsourcing: Its impact on absenteeism in the public sector. Viešoji Polit. Ir Adm. 2004, 7, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wagar, T.H. Exploring the consequences of workforce reduction. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 1998, 15, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saïd, T.; le Louarn, J.-Y.; Tremblay, M. The performance effects of major workforce reductions: Longitudinal evidence from North America. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 2075–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, L. Understanding Ageing Public Sector Workforces: Demographic challenge or a consequence of public employment policy design? Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 1030–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, G.; Hayllar, M.R. Creating Public Value in E-Government: A Public-Private-Citizen Collaboration Framework in Web 2.0. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2010, 69, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, K.F.; Folmer, H. Does Privatization Improve Job Satisfaction? The Case of Ghana. World Dev. 2007, 35, 1779–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambhampati, U.; Howell, J. Liberalization and labor: The effects on formal sector employment. J. Int. Dev. 1998, 10, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Panchanatham, N. Reform and privatization of state-owned enterprises in India. Reforming State-Own. Enterp. Asia Chall. Solut. 2021, 1, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Dincecco, M. Fiscal centralization, limited government, and public revenues in Europe, 1650–1913. J. Econ. Hist. 2009, 69, 48–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffa, F.; Piolatto, A.; Ponzetto, G. Political Centralization and Government Accountability. Q. J. Econ. 2015, 131, 381–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joulfaian, D.; Marlow, M.L. Centralization and government competition. Appl. Econ. 1991, 23, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, T.; Tabellini, G. Does centralization increase the size of government? Eur. Econ. Rev. 1994, 38, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, K.T.; Wang, X. Managerial Value, Financial Condition, and Downsizing Reform: A Study of U.S. City Governments. Public Pers. Manag. 2019, 48, 471–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, M.; Maclsaac, D. Earnings and Welfare after Downsizing: Central Bank Employees in Ecuador. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1999, 13, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, G.; Savage, S.; Kemp, S. Measuring public sector efficiency: A study of economics departments at Australian universities. Educ. Econ. 1997, 5, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inua, O.I.; Maduabum, C. Performance efficiency measurement in the Nigerian public sector: The Federal Universities Dilemma. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, R.D.; Zatzick, C.D. The effects of downsizing on labor productivity: The value of showing consideration for employees’ morale and welfare in high-performance work systems. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 50, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, T.F.; Clancy, D.K. Downsizing and performance: An empirical study of the effects of competition and equity market pressure. Adv. Manag. Account. 2000, 9, 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Straatmann, T.; Mueller, K.; Liu, B. Employees’ Change Support in the Public Sector—A Multi-Time Field Study Examining the Formation of Intentions and Behaviors. Public Adm. Rev. 2021, 81, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranse, J.; Arbon, P.; Cusack, L.; Shaban, R.Z.; Nicholls, D. Obtaining individual narratives and moving to an intersubjective lived-experience description: A way of doing phenomenology. Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.M. Determining sample size. Qual. Health Res. 2000, 10, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.S.; Casey, E.A. An examination of the sufficiency of small qualitative samples. Social Work Res. 2019, 43, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Hassan, H.A.; Al-Ahmedi, M.W.A. Motivations of government-sponsored Kurdish students for pursuing postgraduate studies abroad: An exploratory study. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2017, 21, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamerschlag, R.; Möller, K.; Verbeeten, F. Determinants of voluntary CSR disclosure: Empirical evidence from Germany. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2011, 5, 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krot, K.; Rudawska, I. The Role of Trust in Doctor-Patient Relationship: Qualitative Evaluation of Online Feedback from Polish Patients. Econ. Sociol. 2016, 9, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.; Kumar, M. A systematic approach to conducting review studies: An assessment of content analysis in 25 years of I.B. research. J. World Bus. 2018, 53, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geys, B.; Sørensen, R.J. Never change a winning policy? Public sector performance and politicians’ preferences for reforms. Public Adm. Rev. 2018, 78, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivian, B.; Maroun, W. Progressive public administration and new public management in public sector accountancy. Meditari Account. Res. 2018, 26, 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oana-Ramona, L.; Cristina, N.A. Controversies and Perspectives on Public Sector Performance Measurements. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Ser. Econ. Sci. 2012, 12, 1199–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Kealesitse, B.; O’Mahony, B.; Lloyd-Walker, B.; Polonsky, M.J. Developing customer-focused public sector reward schemes: Evidence from the Botswana government’s performance-based reward system (PBRS). Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2013, 26, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, T.; Laihonen, H.; Haapala, P. Why is dialogue on performance challenging in the public sector? Meas. Bus. Excell. 2018, 22, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W.F. Downsizing: What do we know? What have we learned? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1993, 7, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poister, T.H. Measuring Performance in Public and Non-profit Organizations, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Markic, D. A review on the use of performance indicators in the public sector. Tem. J. 2014, 3, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, W.M.; Wright, P.M. Measuring organizational performance in strategic human resource management: Problems, prospects, and performance information markets. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1998, 8, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompa, V. Managerial secrecy: An ethical examination. J. Ethics 1992, 11, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W.F. Strategies for responsible restructuring. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2002, 16, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Park, J. The effect of downsizing on the financial performance and employee productivity of Korean firms. Int. J. Manpow. 2006, 27, 230–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, B.G.; Senathip, T. Layoffs and Downsizing Implications for the Leadership Role of Human Resources. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2020, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Héritier, A. Composite Democracy in Europe: The Role of Transparency and Access to Information. J. Eur. Public Policy 2003, 10, 814–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Essawi, I. Toward a realistic view of planning and market economy. Arab. Econ. Res. J. 1996, 3, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandru, C.M. The Implications of Privatization to the Organization Model of Constanta Port. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 15, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Waterhouse, P. Privatization: Learning the Lessons from the UK; Experience: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotti, B.; Fantini, M.; Siniscalco, D. Privatization around the world: Evidence from panel data. J. Public Econ. 2003, 88, 305–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, P. Centralization and innovation performance in an emerging economy: Testing the moderating effects. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2014, 32, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinsonneault, A.; Kraemer, K.L. The impact of information technology on the middle management workforce. MIS Q. 1993, 17, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunderson, J.S.; Reagans, R.E. Power, status, and learning in organizations. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1182–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.S.; Sims, D.E.; Lazzara, E.H.; Salas, E. Trust in Leadership: A Multi-Level Review and Integration. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 606–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interviewee No. | Gender | Position in Public Sector | Age | Years in Institution | Total Years in Public Sector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | Deputy Minister of Planning | 43 | 14 | 15 |

| 2 | M | President of The Statistics Authority | 48 | 11 | 20 |

| 3 | M | General Manager | 42 | 2 | 15 |

| 4 | M | General Manager of Health Projects | 50 | 1 | 12 |

| 5 | M | Parliament Member | 43 | 2 | 12 |

| 6 | F | General Manager | 41 | 4 | 16 |

| 7 | M | General Account Manager | 46 | 7 | 22 |

| 8 | M | Ministry of Electricity | 54 | 2 | 29 |

| 9 | M | Ministry of Interior | 51 | 2 | 20 |

| 10 | M | General Director of The Ministry of Electricity | 41 | 10 | 21 |

| 11 | F | Ministry of State for Parliament Affairs | 45 | 2 | 21 |

| 12 | M | Consultant | 43 | 23 | 23 |

| 13 | M | Deputy Minister of Ministry of Industry and Trade | 49 | 1 | 25 |

| 14 | F | Dean at Salahaddin University | 52 | 4 | 28 |

| 15 | M | Parliament Consultant | 50 | 1 | 14 |

| 16 | M | Director of Communication in Office of President | 39 | 12 | 12 |

| 17 | M | Senior Manager in Ministry of Finance and Economy | 48 | 6 | 18 |

| 18 | F | General Account Manager | 39 | 4 | 15 |

| 19 | M | Parliament Consultant | 44 | 8 | 22 |

| 20 | F | General Manager | 47 | 9 | 23 |

| Main Theme: Downsizing | (%) | Main Theme: Public Sector Performance | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reducing the Number of People | 29.3 | Know-How | 35.1 |

| Reducing Budgets and Expenses | 17.1 | System and Quality | 16.2 |

| Reducing the Size | 17.1 | Outcome of the Tasks and Duties | 16.2 |

| Removing or Merging Several Administrative Units | 9.8 | Providing Activities and Services | 13.5 |

| Redesigning Structure of the Government | 9.8 | Time, Cost and Quality of Implementation | 13.5 |

| Privatization | 4.9 | Efficiency | 5.4 |

| hiring More Qualified Staff | 4.9 | ||

| Downsizing Resources | 4.9 | ||

| Changing Culture and Values | 2.4 |

| Subdimension of Public Sector Downsizing | Subdimensions of Public Sector Performance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | % | Effectiveness | % | Transparency | % | Accountability | % | |

| Downsizing in the budgeting of the government | Improving Effectiveness | 31.8 | Negative Impact | 34.8 | Clarifying Implementation of Tasks and Outcomes | 40.0 | Responsibility of Performance | 54.5 |

| Planning | 22.7 | Effective Performance | 21.7 | Reducing Corruption | 20.0 | Achieving Strategic Objectives | 18.2 | |

| Reducing Unnecessary Expenditures | 18.2 | Achieving Functionality | 13.0 | Knowledge | 20.0 | Effective Planning | 9.1 | |

| Redistributing Human Resources | 9.1 | Arranging Laws and Regulations and Reducing Size | 8.7 | Eliminating the Waste of The Budget Codes | 20.0 | Culture and Society | 9.1 | |

| Reorganizing the Size of the Government | 9.1 | Preventing Increasing Size | 8.7 | Negative Expectations | 9.1 | |||

| Modern Technology | 4.5 | Supervision | 4.3 | |||||

| Ethical Considerations | 4.5 | Relationship between Citizens and Government | 4.3 | |||||

| Reducing Expenses | 4.3 | |||||||

| Subdimension of Public Sector Downsizing | Subdimensions of Public Sector Performance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | % | Effectiveness | % | Transparency | % | Accountability | % | |

| Downsizing in the Number of Employees | Redistributing Tasks and Duties | 27.3 | Managing Process Effectively | 48.1 | Determining Unnecessary Employees | 50 | Responsibility | 64.7 |

| Improving Efficiency | 27.3 | Improving Public Performance | 14.8 | Distribution of Salaries and Services | 16.7 | Redistributing Duties and Regulations | 17.6 | |

| Improving Performance | 13.6 | Effective Decisions | 11.1 | Decreasing Corruption | 16.7 | Motivation | 5.9 | |

| Planning | 13.6 | Help to Define Labor | 11.1 | Accountability Towards Quality and Planning | 8.3 | Recommendation of the Political Parties | 5.9 | |

| Quality of Employee | 13.6 | Creativity | 3.7 | Planning | 8.3 | Controlling | 5.9 | |

| Reducing Expenses | 4.5 | Rate of the Reduction | 3.7 | |||||

| Preservation | 3.7 | |||||||

| Responsibility | 3.7 | |||||||

| Subdimension of Public Sector Downsizing | Subdimensions of Public Sector Performance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | % | Effectiveness | % | Transparency | % | Accountability | % | |

| Downsizing in the Structure of Government (Privatization) | Solving Public Problems | 21.4 | Effective Performance | 31.8 | Better transparency | 42.9 | Developing Productive Capabilities | 21.4 |

| Capability | 17.9 | Benefit from Private Sector Capabilities | 31.8 | Controlling Expenditures and Regulations | 28.6 | Raising Level of Responsibility | 14.3 | |

| Raising Efficiency | 14.3 | Setting Conditions and Instructions | 10.1 | Presenting More Knowledge | 14.3 | Improving Accountability | 14.3 | |

| Knowledge | 10.7 | Privatization in Some Parts of Institution | 9.3 | Presenting Right Information to Public | 14.3 | Providing Political Stability | 7.1 | |

| Organizing and Planning | 10.7 | Time | 7.5 | Employee’s Ability | 7.1 | |||

| Improving Efficiency in Service | 7.1 | Sharing Technical Work with Private Sector | 5.5 | Adopting Principles | 7.1 | |||

| Best Opportunities | 3.6 | Distributing Roles between both the Public and Private Sector | 4.0 | Negative Impact | 7.1 | |||

| Helping to Solve Problems | 3.6 | Providing Foreign Investment | 7.1 | |||||

| Creating Competitive Environment | 3.6 | Power of Private Sector | 7.1 | |||||

| Specialization | 3.6 | Reducing the Size | 7.1 | |||||

| Arranging Labor Activities | 3.6 | |||||||

| Subdimension of Public Sector Downsizing | Subdimensions of Public Sector Performance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | % | Effectiveness | % | Transparency | % | Accountability | % | |

| Downsizing in the Centralization of the Government | Negative Impact | 21.1 | Effectiveness | 31.8 | Improving Transparency | 30 | Improving Accountability | 29.4 |

| Particular Areas | 21.1 | Merging the Policy and Mission | 18.2 | Relating Decisions | 20 | Relating Authorities and Decisions | 29.4 | |

| Making Decisions | 10.5 | Relating Political Parties | 13.6 | Designing Responsibilities | 15 | Leading the Responsibility of the Public Sector | 23.5 | |

| Reducing Corruption | 10.5 | Relating Size and Authority | 9.1 | Authorities and Revenues | 10 | Services | 5.9 | |

| Creating Energy | 5.3 | Providing Military and Financial Situations | 9.1 | Better Results in Financial Issues | 10 | Emergency Situations | 5.9 | |

| Saving Time | 5.3 | Maintaining the Available Economic Capabilities | 9.1 | Negative Way | 5 | More Centralized Government | 5.9 | |

| Obstacles with regard to Centralization | 5.3 | Negative Impact | 4.5 | High Formalization | 5 | |||

| Financial Decisions and Issues | 5.3 | Controlling Budget | 4.5 | Providing Opportunities | 5 | |||

| Reducing the Number of Routines in the Process | 5.3 | |||||||

| Increasing Efficiency of Public Sector | 5.3 | |||||||

| Applying Administrative and Economic Centralization System | 5.3 | |||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kazho, S.A.; Atan, T. Public Sector Downsizing and Public Sector Performance: Findings from a Content Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052989

Kazho SA, Atan T. Public Sector Downsizing and Public Sector Performance: Findings from a Content Analysis. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052989

Chicago/Turabian StyleKazho, Shahram Ali, and Tarik Atan. 2022. "Public Sector Downsizing and Public Sector Performance: Findings from a Content Analysis" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052989

APA StyleKazho, S. A., & Atan, T. (2022). Public Sector Downsizing and Public Sector Performance: Findings from a Content Analysis. Sustainability, 14(5), 2989. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052989