Cemeteries as a Part of Green Infrastructure and Tourism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

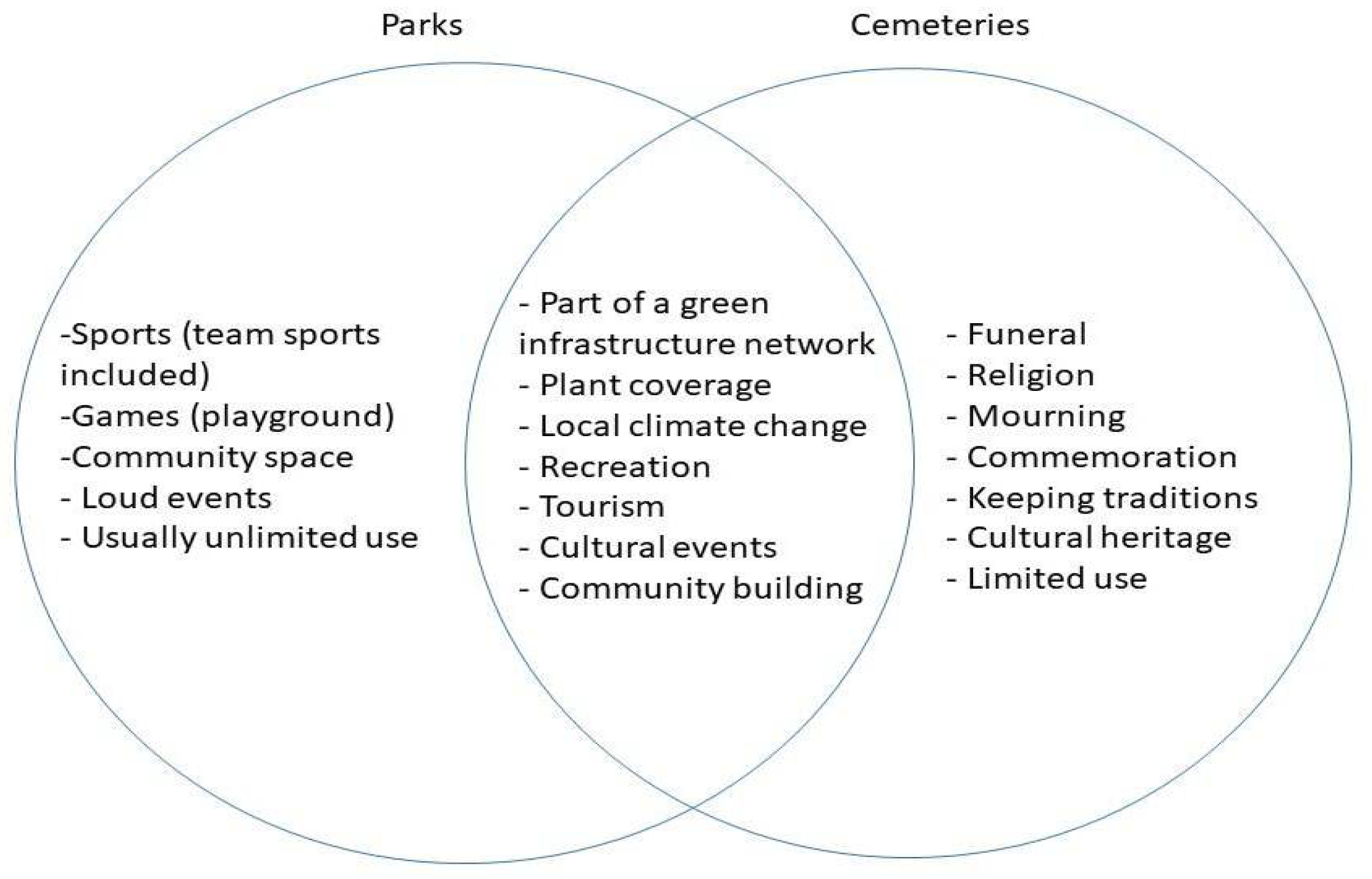

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.1.1. Cemeteries and Recreation

1.1.2. Cemeteries and Tourism

1.1.3. Summary of the Literature Search

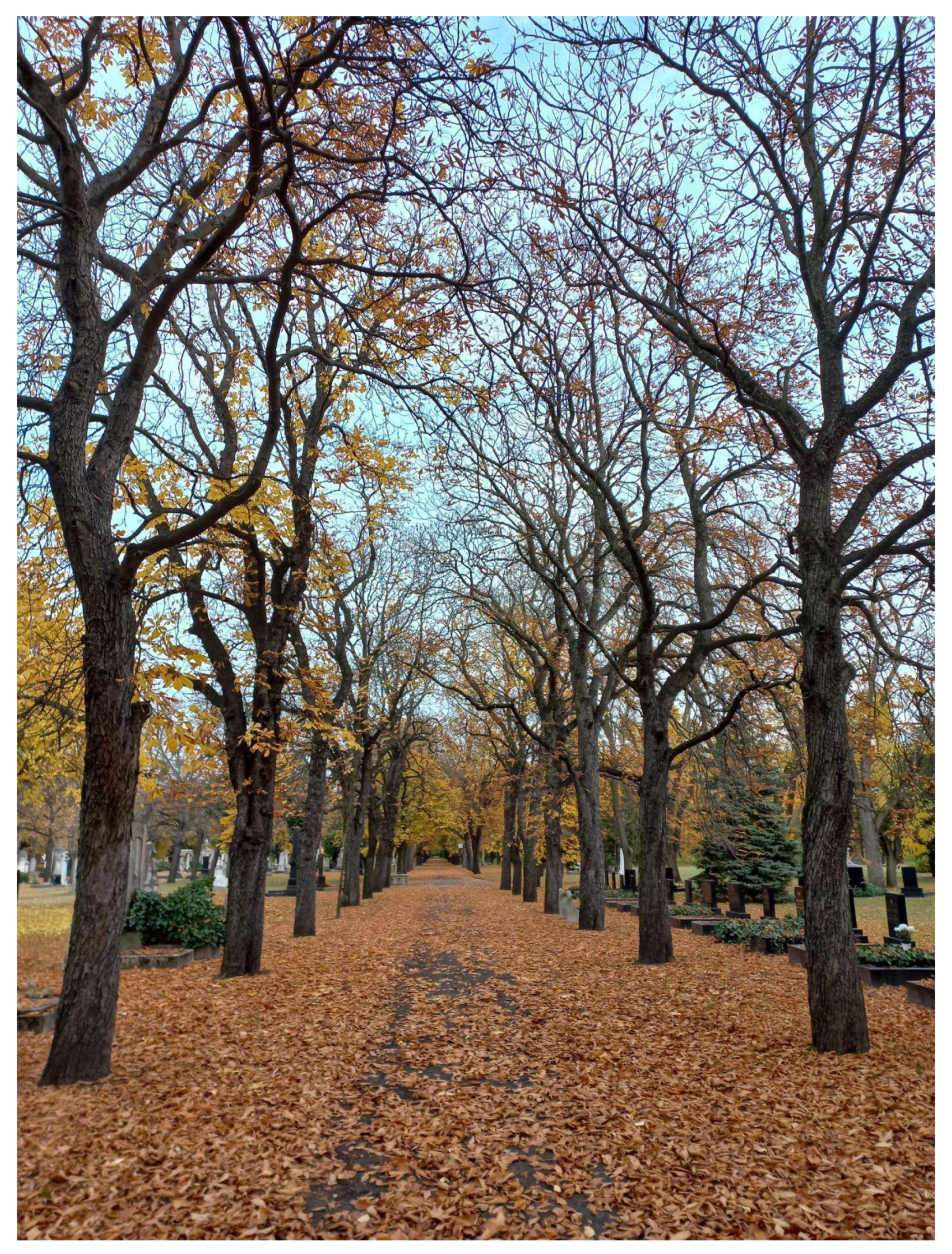

1.2. Presentation of the Sample Area: Green Infrastructure and Cemeteries of Budapest

1.3. Green Infrastructure Network of Budapest and the Role of Cemeteries in the Capital Today

- lack of natural evaporative surfaces

- concrete and asphalt surfaces in cities absorb more solar radiation than they reflect

- vertical surfaces increase the absorption of radiation

- human activity generates heat in many different ways

- pollutants greatly modify the atmosphere

1.4. Touristic Activities in Cemeteries

- Classical music and rock concerts have been organized

- Sports facilities were developed, e.g., a running track was arranged in the cemetery,

- and electric bicycles for hire and carriage rides are offered as new services

- Regular night-time opening during the month of October to give visitors a night-time view of the cemetery

- Music walks offered, with live music accompanying the walkers

- Painting course offered, where visitors can create their own artwork souvenir of the cemetery

- A cemetery museum has been opened where visitors can learn about the history of the cemetery and the famous people buried there

- Nature-focused guided walks and camps for children

- A café and gift shop have been opened at the cemetery gate

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- Basic motivation: visiting family graves. This includes visiting, searching one’s own or others’ family roots and genealogy. A place of confrontation with mortality.

- (2)

- Cultural motivation: the cemetery as an open-air museum, a repository of material and spiritual treasures.

- (i)

- Graves of famous people (kings, presidents, politicians, artists, writers, poets, actors, scientists, etc.)

- (ii)

- Architectural curiosities (emblematic constructions, crypts, mausoleums, etc.)

- (iii)

- Sculptural curiosities

- (iv)

- Places of interest, or a place of personal interest (e.g., the cemetery is featured in a film or a book), ideal for practicing a hobby (e.g., photography, painting)

- (v)

- A “must see” place, i.e., it is on the World Heritage List or on Tripadvisor

- (3)

- National sentiment: visiting memorial parks, military cemeteries; participating on different on-site memorial events

- (4)

- Admiration/love of nature: visiting cemeteries as other parks and arboretums. Special botanical and garden architecture interests, or more generally, a reason for escaping from urban pressures and providing relaxation and recreation

- (5)

- Education and research: visits driven by an interest in history and culture. Visitors especially come to learn more about the history of the cemetery, the place where it was established, and the people who are buried there

- (6)

- Religious motivation (pilgrimage): visiting graves of significant religious/ecclesiastical personalities (e.g., popes, church leaders) or tombs of religious and/or historical significance (e.g., the tomb of Jesus in Jerusalem). A place of confrontation with mortality

- (7)

- The cemetery is an open-air leisure site with organized programs; visiting a concert or a performance in a cemetery

- (8)

- No motivation: unplanned visits. No specific interest in the special features and offerings of the cemeteries. Curiosity, “let’s see what we can find here” attitude

3. Results

3.1. Results of Research on Visitor Motivations

3.2. Results of Questionnaire Survey

3.2.1. Results of Visitor Questionnaire Survey

3.2.2. Results of Guide Questionnaire Survey

4. Discussion

- (1)

- In terms of tourist attractions and sights, the surveyed cemeteries are well-endowed. However, there is an urgent need to collect and identify these assets and values as thematic tourist attractions and to make their relevant information available to visitors. It is important to bear in mind that the cemeteries were not created for tourism purposes. They have gradually become tourist attractions throughout history. Thus, their primary function should not be negatively affected by their use for tourism and recreation. Although cemeteries are not yet conventional touristic destinations in Hungary, they have the potential to become more attractive in the future; their natural, built, and spiritual value and the tangible and intangible heritage they involve reinforce each other. Thus, cemeteries can be identified as open-air recreational areas with several attractions, where the past and present of a settlement as well as its development can be explored in a relatively small area during an individual or guided walking tour. Another beneficial factor is that most municipal cemeteries are open for a wide range of hours and are usually free of charge for visits. Attractiveness can be further enhanced by improving organized cultural programs and events on site. Depending on the cemetery, this could be the development of an existing attraction or the creation of a new one by unique or complex product improvement. This latter may include singular interventions as enhancements of the immediate surroundings around a main attraction, as well as any green space development.

- (2)

- We have found a number of shortcomings in the tourist infrastructure of the cemeteries surveyed on the basis of both our personal site visits and the questionnaire responses. Tourism infrastructure in this case refers to the whole of the welcoming facilities, i.e., those infrastructural elements that can be used by the general public and that enable touristic activities. The improvement of basic tourism services and their background infrastructure is essential and covers, in particular, the development of utilities and pathway systems in a graveyard. This is important for the needs of both tourists and everyday visitors. For recreational and touristic purposes, it is important to provide the essential conditions for a longer stay. For example, there is a fundamental need to provide more benches and basic services such as restrooms. Improving accessibility in general is usually linked to complex touristic and infrastructural development, and is certainly a critical issue. The development of other services that serve mainly tourists, such as souvenir shops, should be preferably developed only after basic service needs have been satisfied.

- (3)

- There are major gaps in the use of visitor management tools. In the case of historic cemeteries, reconciling their original function with touristic uses requires due diligence. Problems related to touristic use can be avoided or solved by using appropriate management methods. For example, problems are often caused by lack of infrastructure (toilets, cleaning facilities, catering facilities), resulting in pollution and litter issues, or by tourists/visitors disturbing mourners and commemorators with their constant presence, talking, or general loudness. Solutions could include the preparation of visitor management tools, planning the movement of visitors in advance, better managing the potential negative impact of visits, and avoidance or mitigatation of negative consequences. Passive exhibition techniques appropriate to the character of the cemetery may be good practice for visitor education, although in most cemeteries only an overview map of the cemetery layout is displayed. There are rarely any signs or printed materials (brochures, guides, and more detailed special publications) providing information on the specific values and attractions of the cemeteries and visualizing their locations. For larger cemeteries, it is necessary to develop thematic itineraries for guided tours or self-exploration walks. During self-guided tours, visitors can follow a pre-edited brochure along the way.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NÖRI | Nemzeti Örökség Intézete—National Heritage Institute |

| BTI | Budapesti Temetkezési Intézet—Budapest Funeral Institute |

| MAZSIHISZ | Magyarországi Zsidó Hitközségek Szövetsége—Federation of Hungarian Jewish Communities |

Appendix A

| Operating Public Cemeteries | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name of the Cemetery | Location in Budapest | Cemetery Management | Features |

| Cemetery in Óbuda (Óbudai temető) | 3rd district | BTI | guided tours |

| Tamás Street Urn Cemetery (Tamás utcai urnatemető) | 3rd district | BTI | urn cemetery on the site of the former Békásmegyeri cemetery |

| Megyeri Cemetery (Megyeri temető) | 4th district | BTI | extension of the former village cemetery |

| National Graveyard on Fiumei Road = Kerepesi cemetery (Fiumei úti sírkert = Kerepesi temető) | 8th district | NÖRI | national pantheon, guided tours |

| New Public Cemetery in Rákoskeresztúr (Rákoskeresztúri Új Köztemető) | 10th district | BTI | the largest cemetery in Hungary, guided tours |

| Farkasréti Cemetery (Farkasréti temető) | 11th district | BTI | the largest cemetery in Buda, guided tours |

| Cemetery in Rákospalota (Rákospalotai temető) | 15th district | BTI | extension of a former village cemetery |

| Cemetery in Cinkota (Cinkotai temető) | 16th district | BTI | extension of a former village cemetery |

| Cemetery in Pestszentlőrinc (Pestszentlőrinci temető) | 18th district | BTI | extension of a former village cemetery |

| Old Cemetery in Kispest (Kispesti Öreg temető) | 19th district | BTI | reopened former village cemetery |

| Cemetery in Kispest (Kispesti temető) | 19th district | BTI | extension of a former village cemetery |

| Cemetery in Pesterzsébet (Pesterzsébeti temető) | 20th district | BTI | extension of a former village cemetery |

| Cemetery in Csepel (Csepeli temető) | 21st district | BTI | extension of a former village cemetery |

| Cemetery in Budafok (Budafoki temető) | 22nd district | BTI | former village cemetery |

| Angeli Road Urn Cemetery (Angeli úti urnatemető) | 22nd district | BTI | urn cemetery on the site of the former Nagytétényi cemetery |

| Operating Jewish cemeteries | |||

| Name of the cemetery | Location in Budapest | Cemetery management | Features |

| Jewish Cemetery in Óbuda (Óbudai izraelita temető) | 3rd district | MAZSIHISZ | |

| Jewish Cemetery in Kozma Street (Kozma utcai izraelita temető) | 10th district | MAZSIHISZ | the largest Jewish cemetery in Hungary |

| Orthodox Jewish Cemetery in Gránátos Street (Gránátos utcai ortodox izraelita temető) | 10th district | MAZSIHISZ | |

| Farkasréti Jewish Cemetery (Farkasréti izraelita temető) | 11th district | MAZSIHISZ | |

Appendix B

- age: 18–25 y, 25–40 y, 40–50 y, 50–60 y, 50–70 y, 70 over

- sex: female/male

- education: 8 primary school, secondary school, university/college

- place of residence: Budapest, Budapest agglomeration, large city, medium-sized city, small town, village, other options to define:

- How often do you visit a cemetery?

- weekly

- several times a month

- on a quarterly basis

- yearly

- less frequently

- yes, I’ve been there less often

- yes, I have gone there more often

- No, it has not changed

- I expected spiritual comfort from the visits

- It was possible to walk and move around the cemetery at a reasonable distance during the closures

- The visit to the cemetery provided a cultural programme

- I expanded my knowledge with what I saw in the cemetery

- other options to define:

- visit the graves of my loved ones/relatives

- remember the deceased (not necessarily in the cemetery where they are buried)

- visit the graves of famous people

- get to know statues, artworks and buildings in cemeteries

- for walking and relaxing

- yes, I mainly visit the graves of relatives and friends

- yes, I visit cemeteries as historical sites

- yes, I visit the graves of famous people

- yes, I visit artworks and statues in cemeteries

- yes, I visit buildings and other architectural elements

- yes, I am interested in the green surface and vegetation of cemeteries (protected and special species)

- yes, other options to define:

- no

- yes, I mainly visit the graves of relatives and friends

- yes, I visit cemeteries as historical sites

- yes, I visit the graves of famous people

- yes, I visit artworks and statues in cemeteries

- yes, I visit buildings and other architectural elements

- yes, I am interested in the green surface and vegetation of cemeteries (protected and special species)

- yes, other options to define:

- no

- yes

- no

- walking

- reading

- contemplating

- doing sport activity (e.g., running)

- other options to define:

- yes

- no

- yes

- no

- yes

- no

- yes

- no

- trees, alleys

- flower beds

- shrubs

- grasslands

- good accessibility

- it should be a closed cemetery (with no more active burials)

- free space between graves

- good coverage of green areas

- other options to define:

Appendix C

- National Graveyard on Fiumei Road (Fiumei úti temető/Kerepesi úti temető)

- Farkasréti Cemetery (Farkasréti temető)

- Jewish Cemetery in Salgótarjáni Road (Salgótarjáni úti zsidó temető)

- other options to define:

- weekly

- once a month

- several times in a month

- a few times a year

- I organize themed cemetery walks on different sites

- I also bring tourists to cemeteries on my sightseeing walks.

- I organise walks only in the National Graveyard on Fiumei Road (Fiumei úti temető/Kerepesi úti temető)

- I organise walks only in the Farkasréti Cemetery (Farkasréti temető)

- I organise walks only in the Jewish Cemetery on Salgótarjáni Road (Salgótarjáni úti zsidó temető)

- other options to define:

- Under 100 people

- Between 100–200 people

- Between 200–500 people

- More than 500 people

- mostly aged between 18–30

- mostly aged between 30–50

- mostly aged between 50–70

- mostly over 70

- the graves of famous people

- the statues in the cemetery,

- notable buildings

- old/notable trees

- other options to define:

- yes, we visit historical sites

- yes, we visit the graves of famous people

- yes, we visit works of art and statues in cemeteries

- yes, we visit them for their architectural values (e.g., buildings)

- yes, I highlight the vegetation of the cemeteries (protected and special species)

- no, I don’t have these kind of activity

- yes

- no

- trees, alleys

- flower beds

- shrubs

- grassland areas

- yes

- no

- parking places

- restroom, toilet

- benches

- souvenir shop

- catering facilities

- other options to define:

- yes

- no

- concert

- exhibition

- theatre performance

- other options to define:

- having good accessibility

- being a closed cemetery

- having enough free spaces between graves

- having good coverage of green spaces

- other options to define:

References

- Eötvös, K. A Balatoni Utazás Vége [The End of the Balaton Trip]; Vitis Aureus Bt.: Budapest, Hungary, 2007; 175p. [Google Scholar]

- Szatmárcsekei Csónakos Fejfás Református Temető [Calvinist Cemetery in Szatmárcseke, Hungary]. Available online: https://reformacio.mnl.gov.hu/orokseg/szatmarcsekei_csonakos_fejfas_reformatus_temeto (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Balatonudvari—Szívalakú Sírkövek [Balatonudvari—Heart-Shaped Gravestones]. Available online: https://www.balatonudvari.hu/balatonudvari-telepules/telepulesunk-kepekben/szivalaku-sirkovek/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Sökfás Temetők az Őrségben [Cemeteries in the Őrség, Hungary]. Available online: http://guide2visit.eu/vonzerok-reszletek/sokfas-temetok-az-orsegben (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Hajdúböszörmény, Kopjafás Temető - Csónakos Fejfás Temető [Cemeteries in Hajdúböszörmény, Hungary]. Available online: https://www.turautak.com/cikkek/latnivalok/szakralis--vallasi-helyek/hajduboszormeny--kopjafas-temeto-csonakos-fejfas-temeto.html (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Katonai Temető, Budaörs [Military Cemetery, Budaörs, Hungary]. Available online: https://airbase.blog.hu/2020/10/29/katonai_temeto_budaors (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Gül Baba Türbéje. [Tomb of Gül Baba’s, Budapest, Hungary]. Available online: https://gulbabaalapitvany.hu/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Világörökség Pécs. [World Heritage Site at Pécs, Hungary]. Available online: https://www.pecsorokseg.hu/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Sallay, Á.; Máté, K.; Mikházi, ZS.; Csemez, A. A Kálváriák Szerepe a Balaton-Felvidék Turizmusában. [The role of calvarias in the tourism of the Lake Balaton region.] In Turizmus 3.0 (Turizmus Akadémia 10); Kátay, Á., Michalkó, G., Rátz, T., Eds.; Kodolányi János Egyetem: Orosháza: Budapest, Hungary, 2019; pp. 72–85. ISBN 978-615-5075-47-6. ISSN 1786-2310. [Google Scholar]

- Mikházi, ZS.; Csemez, A.; Máté, K.; Sallay, Á. The role of calvaries in Hungarian religious tourism. J. Tour. Chall. Trends Tour. Relig. 2016, 9, 65–92, ISSN 1844-9742. [Google Scholar]

- Gecséné Tar, I.; Hajdu Nagy, G. Südwest-Kirchhof, Stahnsdorf—Egy Temető Újjászületése. [Südwest-Kirchhof, Stahnsdorf—A Cemetery Rebirth.] Tájépítészet 2005, 6, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gecséné Tar, I. Történeti Temetők Magyarországon; Doktori értekezés, Budapesti Corvinus Egyetem: Budapest, Hungary, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gecse-Tar, I.; Takács, K.; Bechtold, Á. The Hungarian National Graveyard (Budapest) as a public park. Teka Kom. Urban. Archit. 2016, 44, 187–193. Available online: http://teka.pk.edu.pl/index.php/tom-xliv-2016-2/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Prater, T. Cemetery Tourism—A New Trend? Available online: https://travelinspiredliving.com/cemetery-tourism-new-trend/ (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Quinton, J.M.; Duinker, P.N. Beyond burial: Researching and managing cemeteries as urban green spaces, with examples from Canada. Environ. Rev. 2019, 27, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaś, S. The cemetery as a part of the geography of tourism. Turyzm 2004, 14, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skår, M.; Nordh, H.; Swensen, G. Green urban cemeteries: More than just parks. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2018, 11, 362–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deering, B. In the Dead of Night. In The Power of Death: Contemporary Reflections on Death in Western Society; Blanco, M.J., Vidal, R., Eds.; Berghan Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Evensen, K.H.; Nordh, H.; Skaar, M. Everyday use of urban cemeteries: A Norwegian case study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 159, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClymont, K.; Sinnett, D. Planning Cemeteries: Their Potential Contribution to Green Infrastructure and Ecosystem Services. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 789925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinkovic, L. Issues of Croatian Touristic Identity in Modern Touristic Trends. J. Tour. Res. Hosp. 2016, 5. Available online: http://www.scitechnol.com/peer-review/issues-of-croatian-touristic-identity-in-modern-touristic-trends-VJGq.php?article_id=4907 (accessed on 12 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Millán, M.G.D.; Naranjo, L.M.P.; Rojas, R.D.H.; De La Torre, M.G.M.V. Cemetery tourism in southern Spain: An analysis of demand. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 25, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliberšek, L.; Vrban, D. Cemetery as Village Tourism Development Site. In 4th International Rural Tourism Congress, Congress Proceedings; 2018; pp. 194–209. Available online: https://www.fthm.uniri.hr/images/kongres/ruralni_turizam/4/znanstveni/Plibersek_Vrban.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- European Cemeteries Route. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cultural-routes/the-european-cemeteries-route (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Nagy, K. Közparkok és Közkertek Használatának Vizsgálata és Értékelése [Survey and Evaluation of the Use of Public Parks and Gardens]; Kandidátusi értekezés, Kertészeti és Élelmiszeripari Egyetem: Budapest, Hungary, 1997; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Balogh, P.I. A Szabadterek Szerepváltozása a Nagy Európai Városmegújításokban. [The Changing Role of Open Spaces in the Great European Urban Renewal.]. Ph.D. Thesis, BCE, Budapest, Hungary, 2006; pp. 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Csernus-Lukács, L.; Triff, V.; Zsigmond, J. Budapesti Temetők [Cemeteries in Budapest]; A mi Budapestünk Sorozat: Budapest, Hungary, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Seléndy, S.Z. Temetőkert [Cemetery gardens]; Mezőgazdasági Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bakay, E. Lakótelepek Szabadtérépítészete 1945–1990 Között Budapest Példáján. [Open Space Architecture of Housing Estates in Budapest 1945–1990.]. Ph.D. Thesis, BCE, Budapest, Hungary, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Budapest Környezeti Állapotértékelése [Budapest’s Environmental Assessment]. 2021. Available online: https://budapest.hu/Lapok/2020/budapest-kornyezeti-allapotertekelese.aspx (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- European Environment Agency Report: Urban Adaptation to Climate Change; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark. 2012. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/urban-adaptation-to-climate-change (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Rizwan, A.M.; Dennis, L.Y.C.; Liu, C. A review on the generation, determination and mitigation of Urban Heat Island. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleerekoper, L.; Van Esch, M.; Salcedo, T.B. How to make a city climate-proof, addressing the urban heat island effect. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 64, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Baudouin, Y.; Gachon, P. An alternative method to characterize the surface urban heat island. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014, 59, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radó Dezső terv: Budapest Zöldinfrastruktúra Fejlesztési és Fenntartási Akcióterve [Radó Dezső Plan: Budapest’s Green Infrastructure Development and Maintenance Action Plan]; Főváros Önkormányzata: Budapest, Hungary, 2021.

- Anna, D.; Ewa, K.-B. How to Enhance the Environmental Values of Contemporary Cemeteries in an Urban Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Budapest Környezeti Állapotértékelése 2019–2020 [Budapest’s Environmental Assessment 2019-2020], II.7. Zöldfelület-Gazdálkodás. Available online: https://budapest.hu/Documents/BKAE/2019-2020/27_BK%C3%81%C3%89-2020_II-7-Z%C3%B6ldfel%C3%BClet-gazd%C3%A1lkod%C3%A1s.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; O’Neill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D.; Minor, E. Chicago’s Urban Cemeteries as Habitat for Cavity-Nesting Birds. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Konic, J.; Essl, F.; Lenzner, B. To Care or Not to Care? Which Factors Influence the Distribution of Early-Flowering Geophytes at the Vienna Central Cemetery (Austria). Sustainability 2021, 13, 4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Evensen, H.K. Qualities and functions ascribed to urban cemeteries across the capital cities of Scandinavia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 33, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sírkerti Séták [Graveyard Walks]. Available online: https://fiumeiutisirkert.nori.gov.hu/sirkerti-setak (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Sétaműhely Séták [Sétaműhely Walks]. Available online: https://setamuhely.hu/seta (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Budapesti Temetkezési Intézet. Available online: https://www.btirt.hu (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Südwestkirchhof Stahnsdorf. Available online: www.suedwestkirchhof.de (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Friedhöfe Wien. Available online: www.friedhoefewien.at (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Tomašević, A. Cemeteries as tourist attraction. Tur. Posl. 2018, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreno, A.S. Cemetery Tourism: Visitors’ Motivations for Visiting the Rakowicki Cemetery in Kraków. Master’s Thesis, Universitat de Girona, Girona, Spain, 2018; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Pécsek, B. City Cemeteries as Cultural Attractions: Towards an Understanding of Foreign Visitors’Attitude at the National Graveyard in Budapest. Deturope 2015, 7, 44–61. Available online: http://www.deturope.eu/img/upload/content_42123976.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Rátz, T. Mindenszentek és Halottak Napja Szerepe a Magyar Lakosság Utazási Magatartásának Befolyásolásában. [The role of All Saints’ Day and Day of the Dead in influencing the travel behaviour of the Hungarian people.]. Tur. Bull. 2006, X/3, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Balajti, P. Élettel Töltenék Meg a Temetőket [Fill the Cemeteries with Life.]. Available online: https://www.borsonline.hu/aktualis/2013/08/elettel-toltenek-meg-a-temetoket (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Nemzeti Örökség Intézete. Sajtószemle: Ősz a Fiumei úti sírkertben. [National Heritage Institute. Press Review: Autumn in the Fiumei út Cemetery.] (2021. Október 30). Available online: https://intezet.nori.gov.hu/hirek/osz-a-fiumei-uti-sirkertben/ (accessed on 5 January 2022).

| Period | Urban Green Areas | Cemeteries |

|---|---|---|

| until the end of the Turkish occupation | small vegetable gardens, private residential gardens, extended agricultural land | cemeteries next to churches, burial places |

| 1700s | increasing density of urban development leading to an emerging need for public green spaces and parks | cemeteries appear on the outskirts of the settlement, independently of churches |

| 1800s | first public parks, large boulevards with alleys, afforestation, public squares and pedestrian areas with numerous trees | large new cemeteries established on the outskirts of the city. with the burial function remaining primary |

| 1872–1945 | more leisure activities in public parks; the first public playgrounds | large new cemeteries opened on the outskirts of the city due to rapid urban development, in which the graves of famous people become urban pilgrimage sites. |

| 1945–1990 | in parallel with the construction of housing estates, public green spaces around them are created; the first protected green areas are designated in the city, and park woodlands become significant | former village cemeteries around Budapest annexed to the capital by the creation of peripheral areas (many of which have been dismantled, although a few remain in use today), either as extensions or as urn cemeteries; cemeteries popular for recreational purposes thanks to attractive mature vegetation |

| 1990s | new residential and office developments created on brownfield sites, increased building density, growing demand for open greenspace | tourist use of cemeteries, mainly guided walks around the graves of famous people and tertiary usage such as classical music concerts and exhibitions |

| 2020 | pandemic closures have pushed people even more towards urban green spaces, for which demand has increased, and many have become overused | during lockdowns, people spend part of their recreational time in cemeteries, and mourning also ‘attracts’ more and more people to cemeteries |

| Organizing Institute or Company | The Name or the Theme of Walks and Guided Tours |

|---|---|

| Sétaműhely Ltd. | Trees and headstones—guided walks in the Farkasréti Cemetery On the trails of Kohanites |

| Imagine Budapest (Sétapálca Ltd.) | A past encased in stones—a tour of the Salgótarjáni Street Jewish Cemetery |

| Nemzeti Örökség Intézete (NÖRI) National Heritage Institute | Parcels of artists “Faster, Higher, Stronger”—Olympic medalists in the National Graveyard “On hidden pathways”—cycling tour in the National Graveyard on Fiumei Road Celebrated gipsy violinist First World War—Military tombs 19th century’s prime ministers Musician souls The artists of the “Nyugat” generation Under the spell of “Thália” The masters of Hungarian painting The death cult of the socialism The secrets of the plot 301—What do the graves tell us? The Prime Ministers of the 20th century Inventors and engineers In the footsteps of great travelers The gravestone artworks of Béla Lajta in the Jewish cemetery on Salgótarjáni Street Budapest, Budapest, so wonderful The life of an artist in sculptures Sacred depictions in funerary art of tombs In the footsteps of the Piarist Fathers and their disciples Mausoleums and the National Graveyard on Fiumei Road Those doomed to oblivion—Specific interpretation walk Graves in the garden—plants and symbols in the cemetery “That soul in me...”—Literary walk in the cemetery Immortal art—Sculptors and sculptures Remembering 1848–49 Ferenc Deák and his generation Memento ’56 History of the Jewish cemetery on Salgótarjáni street Women, Muses, Destinies Women on the trail of success Gastro moods Family walk with the little ones Go, Hungarians! Athletes and sports leaders Irregular school lessons in the cemetery Secrets of an oasis in the heart of the city—The National Graveyard on Fiumei Road (guided walk in English language) |

| Budapesti Temetkezési Intézet (BTI) Budapest Funeral Institute | Guided walks in the Farkasréti, Óbudai and Rákoskeresztúri Cemeteries |

| Visitor Motivations | Attractions | Representative Cemeteries |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Basic motivation | tombs and crypts of families | All functioning cemeteries |

| 2. Cultural motivation | ||

| 2.1. graves of famous people | graves of kings, presidents, politicians, artists, writers, poets, actors, scientists, etc. | National Graveyard on Fiumei Road Farkasréti Cemetery New Public Cemetery in Rákoskeresztúr Farkasrét Jewish Cemetery Óbudai Jewish Cemetery Kozma Street Jewish Cemetery Salgótarjáni Street Jewish Cemetery |

| 2.2. architectural curiosities | emblematic constructions, crypts, mausoleums, etc. | National Graveyard on Fiumei Road Farkasréti Cemetery Kozma Street Jewish Cemetery Salgótarjáni Street Jewish Cemetery Budafoki temető |

| 2.3. sculptural curiosities | cross, statue, carving | National Graveyard on Fiumei Road Farkasréti Cemetery Óbudai Cemetery Salgótarjáni Street Jewish Cemetery Óbuda Jewish Cemetery Budafoki Cemetery Kisszentmihályi Cemetery |

| 2.4. places of interest, or a place of personal interest, ideal for practicing a hobby (e.g., photography, painting) | the cemetery is featured in a film or a book | |

| 2.5. a “must see” place | it is on the World Heritage List or on Tripadvisor | |

| 3. National sentiment | memorial parks, military cemeteries graves being attached to wars, monuments of wars | National Graveyard on Fiumei Road New Public Cemetery in Rákoskeresztúr |

| 4. Admiration/love of nature | Special botanical and botany or zoology value | National Graveyard on Fiumei Road Farkasréti Cemetery New Public Cemetery in Rákoskeresztúr Óbudai Cemetery |

| 5. Education and research | curiosity of settlement history | National Graveyard on Fiumei Road Salgótarjáni Street Jewish Cemetery Closed cemeteries outskirt, earlier communal cemeteries |

| 6. Religious motivation (pilgrimage) | tombs of religious and/or historical significance, calvary | All Jewish Cemetery National Graveyard on Fiumei Road |

| 7. Local | organised programs, concert, or a performance | National Graveyard on Fiumei Road |

| 8. No motivation | All functioning cemeteries |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sallay, Á.; Mikházi, Z.; Gecséné Tar, I.; Takács, K. Cemeteries as a Part of Green Infrastructure and Tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052918

Sallay Á, Mikházi Z, Gecséné Tar I, Takács K. Cemeteries as a Part of Green Infrastructure and Tourism. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052918

Chicago/Turabian StyleSallay, Ágnes, Zsuzsanna Mikházi, Imola Gecséné Tar, and Katalin Takács. 2022. "Cemeteries as a Part of Green Infrastructure and Tourism" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052918

APA StyleSallay, Á., Mikházi, Z., Gecséné Tar, I., & Takács, K. (2022). Cemeteries as a Part of Green Infrastructure and Tourism. Sustainability, 14(5), 2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052918