Abstract

This study sought to explore the impact of green human resource management on organizational identification and employees’ eco-friendly behavior, as well as the mediating role of organizational identification in the relationship between green human resource management and employees’ eco-friendly behavior. To achieve the study objectives, a cross-sectional quantitative study was developed, for which the data were obtained through a structured questionnaire containing the measures of the study variables. Data were collected from 235 employees from several Portuguese tourism organizations participating in the study. The Harman test and bootstrapping were applied previously to the assessment of the results. The mediation study’s hypothesis was evaluated using Baron and Kenny’s linear regression method, and subsequently complemented using the Sobel test. The findings showed that the implementation of green HRM practices in tourism organizations has a positive impact on employees’ eco-friendly behavior and on organizational identification, with the latter mediating the relationship between green human resource management and employees’ eco-friendly behavior. The study is breaking new ground because it incorporates the impact of green human resource management on organizational identification and employees’ eco-friendly behavior in a single research model, thus expanding knowledge on the subject, namely in the tourism sector in Portugal.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the tourism industry has been an important driver of employment in Portugal as a result of the public recognition of the country’s excellent tourism conditions [1]. Tourism has become a key economic sector for Portugal during the last few decades due to the outstanding conditions the country has for this purpose. As a result, the country is an award winner in multiple categories of tourist destinations, which express the way this business sector is currently seen by national and international authorities, such as: Europe’s Leading Tourism Destination in 2017, 2018, and 2019 at the World Travel Awards; Madeira was named the World and Europe’s Leading Island Destination in 2017, 2018, and 2019; and Lisbon was named Europe’s Leading Cruise Port in 2018 and 2019. Because of the strong investment the country has made in enlarging its touristic abilities, Portugal currently ranks twelfth in the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index [2] and has gathered much “evidence of the progress Portugal has made in terms of visibility and prestige as a quality destination” [3].

According to Portuguese regional promotional tourism entities, it is possible to define a successful tourism destination as the one that creates income for the local community and ensures the quality of life of the population; values and preserves local identities, heritage, culture and traditions; and promotes the sustainable use of ecosystems and the preservation of natural resources, based on a circular economy approach [4].

In fact, the representativeness of the economic benefits that the tourism sector provides to Portugal is important, however, some researchers have already observed how the effects of climate change may affect these economic activities in the country, a fact that invites researchers and managers to face these challenges for sustainable development [5]. In the tourism industry, there is internal and external pressure to protect the environment through environment-friendly services [5].

Considering this scenario, it has become indispensable for human resource managers to understand how the implementation of good practices of green human resources management (GHRM) in tourism sector organizations can affect the organizations’ environmental performance, and to recognize that these practices can stimulate progress towards environmental sustainability in the workplace [6,7].

With an increasingly competitive market, the real need to focus attention on the implementation of green HRM practices has emerged, as these measures can reveal benefits for organizations, since employees who are more involved in these initiatives can increase the chances of organizations achieving greener and more successful management [6,8]. The importance of developing organizational strategies aimed at enhancing the environmental and financial performance of companies is noteworthy. Implementing initiatives that encourage well-being, environmentally friendly behavior and employee engagement may be the key to success for HRM managers to create a competitive edge, especially in organizations within the tourism industry that exert significant pressure on the environment [9].

Kim et al. [10] clarified that offering education and training programs on environmental protection measures to employees helps them to better understand the importance of environmental conservation and organizations’ environmental policies, consequently, make them more aware. In this sense, employees who are more aware of these benefits can create a feeling of greater identification with their organization because green training should create a positive image of a responsible organization and, as the social identity theory suggests, employees may identify themselves with such organizations [11].

Renwick et al. [8] developed a broad investigation on green HRM, suggesting an agenda of potential research in this field. Although it assessed how green HRM practices can influence workers’ motivation, an opportunity to better understand how these adopted measures can increase employees’ sense of identification with companies was observed.

When a set of ecological concerns are demonstrated on the part of organizations, employees may interpret it as positive support and increase their environmentally friendly behaviors within the organization [12]. The benefits of alignment between employees’ green attitudes and behaviors and organizations’ environmental goals can result in improved company performance and employee well-being [13].

Adopting GHRM practices (e.g., providing green training, and recognizing and rewarding green behavior) provides employees with opportunities to participate and engage in green activities [11]. Based on the theory of social identity [11], employees prefer to identify themselves with organizations that have a reputation/image (e.g., “green” or “eco-friendly”). This could explain the underlying mechanism through which GHRM may promote organizational identification and, consequently, increase eco-friendly behaviors.

Therefore, this study intended to expand the knowledge about how green HRM practices in organizations increase employees’ eco-friendly behaviors and have a positive impact on organizational identification, the latter mediating the relationship between the other two variables, GHRM and employees’ eco-friendly behaviors. This was made possible through data obtained from employees in the tourism sector in Portugal.

To make this possible, this study was organized as follows. Following the introduction, Section 2 presents the literature review, where the hypotheses are shown and developed. The methodology applied in terms of the data collection process, sample size and description, and measurement is included in Section 3. The results, discussion and conclusions, study limitations and suggestions for future research are in Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6, respectively. The final part was reserved for the theoretical contributions provided by the authors and the implications of the study.

2. Theoretical Framework and Development of Hypotheses

2.1. Green HRM and Organizational Identification

Green HRM (GHRM) defines the planning and implementation of human resource management practices and policies aligned with the company’s environmental sustainability goals [8] to guide the employees themselves and have them develop attitudes, behaviors, skills, motivation and commitment to environmental sustainability [10], while promoting a workforce favorably engaged in trying to achieve these more environmentally friendly organizational goals [14,15].

Green-oriented HR initiatives can be seen as an organizational mechanism to try to ensure that employees behave in a “green way” [16]. According to Darvishmotevali and Altinayb [17], green HRM is considered the best way to help organizations implement more sustainable programs, especially by creating “green employees” who can assess environmental issues in the organization’s activities and improve them.

Thus, the development of GHRM in a company involves greener human resource activities to increase environmental benefits [18], such as environmental performance management, green salaries, environmental engagement [19,20] and more sustainable career development practices, contributing to the performance of the organizational environment [21]. In addition, environmental education training will also enable employees to conscientiously participate in green organizational processes, become more involved in environmental management and create a green organizational culture [10,22].

In turn, the tourism sector is facing more and more challenges, particularly in relation to the environment, due to the intense and increasing pressure of its activity on natural resources, which puts its workers on the front line of this daily struggle. However, by implementing green HRM practices, they contribute, even significantly, to decreasing their environmental footprint and carbon emissions [23].

Thus, these practices, in addition to being related to companies’ environmental strategy [21,24], along with organizational goals of a sustainable nature, will reflect their environmental mindset [25]. It is expected that by investing in addressing and promoting environmental concerns through the implementation of GHRM practices, organizations will promote a positive self-image [26]. This proves to be very positive for organizations, as employees themselves prefer to identify with organizations with a high reputation and a good image that will enrich their employees’ self-concept, self-image and self-esteem [27]. Social identity theory provides a theoretical rationale for the relationship between GHRM and organizational identification.

Organizational identification, as a cognitive construct, refers to an individual’s perception of belonging to or being associated with the organization where they work [28,29,30], which helps human resource managers understand how employees are connected to and identify with the company [31]. Organizational identification is a kind of feeling of psychological connection with the organization’s own values [32], which manifests because of employees’ emotional attachment to organizations that show a sense of pride in the social values they uphold [33]. At the individual level, organizational identification is enhanced in companies that are more involved in social responsibility-related activities [34,35,36], with employee perceptions of these activities, in turn, predictably triggering pro-environmental behaviors [37].

Employees identify with the organization when they perceive it to be highly prestigious and to enjoy a positive and attractive image; this organizational identity consequently improves members’ self-esteem [38]. To develop a positive sense of self-worth, people seek to join and remain with high-status organizations because such group membership is gratifying and creates a sense of pride [38]. As such, by adopting GHRM practices, the organization sends a clear message to employees that it is committed to the social green cause beyond any financial benefits [8,38]. Employees are motivated to reply positively to perceived GHRM practices because of their self-enhancement motives [39]. Rangarajan and Rahm [40] found that when firms adopt GHRM practices, they signal to employees that they have a strong corporate social agenda and value the environment. This promotes external prestige, with the organization thus likely to become more “attractive” to employees.

Furthermore, employees are generally attracted to organizations in which they can generate a higher level of organizational identification [41], which, due to greener initiatives and behaviors on the part of the organization, causes them to engage in these activities and develop a more positive attitude towards the organization’s reality [42]. As such, social identity theory would suggest that employees’ perceptions of green HRM will result in employees’ organizational identification [38]. According to the same author, employees’ perceptions of GHRM are positively related to organizational identification.

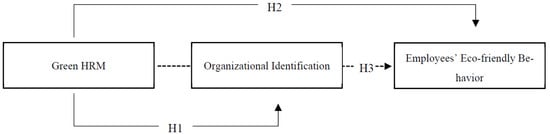

Going through this path, this study came up with Hypothesis 1, in which it is believed that GHRM can positively relates to organizational identification.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Green HRM is positively related to organizational identification.

2.2. Green HRM and Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior

One of several strategies followed by organizations to improve their environmental performance and achieve sustainability goals involves employees’ eco-friendly behaviors [43]. These can be defined as the intentional actions or behaviors of employees that have a favorable effect on the environment, reducing the impact of human actions on the environment and bringing about positive changes for environmental sustainability [41,44,45].

Employees’ eco-friendly behaviors can include activities such as water conservation, efficient use of resources, waste reduction, energy saving and recycling, and can be divided into two types of green behaviors: task green behavior and voluntary green behavior [46]. The first describes green behavior that is performed within organizational constraints, being within the scope of tasks required by the employees’ role in the company; that is, it is about the activities formally described and identified as part of their job description [47]. However, voluntary employee green behavior is defined as green behavior that is developed on the employee’s own personal initiative, exceeding organizational expectations [46].

GHRM can be expected to affect green behaviors, as recruiting employees with environmental awareness and sensitivity, involving them in the implementation of green initiatives and providing green training, for example, are likely to improve employees’ knowledge, skills and environmental awareness, making them more psychologically available to engage in green behaviors [48,49]. The effectiveness of GHRM practices in achieving correct behaviors in the workplace depends on employees’ understanding of the need and urgency to adopt such practices [50,51].

In fact, GHRM practices are significant in developing employees’ environmental values and improving their green behaviors, promoting the need to generate responses to sustainability issues in organizations’ HRM systems and making it necessary to allocate resources that encourage these systems in companies, consequently promoting greener behaviors [13,16,48,52] and thus improving employee outcomes [53]. According to Shen et al. [12], adopting GHRM practices (e.g., providing green training, and recognizing and rewarding green behavior) provides employees with opportunities to participate and engage in green activities. Moreover, the adoption of strategic GHRM policies in organizations to stimulate the development of environmental values among employees can contribute to better business performance and determine a competitive advantage for organizations in the tourism market [10].

In this regard, and according to the existing literature, it is possible to realize that, in fact, the GHRM may have a positive relationship with employees’ eco-friendly behavior, and Hypothesis 2 can be affirmed in this study.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Green HRM relates positively to employees’ eco-friendly behavior.

2.3. Mediating Role of Organizational Identification in the Relationship between Green HRM and Employees’ Eco-Friendly Behavior

Implementing GHRM with the aim of achieving environmental sustainability will not only predictably improve the organization’s image to the outside world but will also increase its prestige and reputation by strengthening its employees’ self-concept and self-esteem, consequently increasing their identification with the organization itself [48,54]. Furthermore, HRM practices that recognize employees’ green contributions, such as green training or a green incentive system, will give employees the opportunity to participate in green initiatives and they are thus likely develop more sustainable behaviors and attitudes on their part [12].

Organizational identification thus emerges as a form of social identification, where an individual develops an emotional attachment or a sense of belonging to the organization where they work [32,55], which is expected to improve the performance of GHRM practices, since the fact that these individuals feel strongly connected to the organization will make them develop more responsible behaviors towards the environment and thus improve environmental performance and organizational sustainability [48,56,57,58,59].

Shah et al. [37] found that organizational identification at the individual level was enhanced when organizations were more involved in corporate social responsibility (CSR)-related activities, and further believed that employees’ perceptions of these activities not only predicted organizational identification but also triggered pro-environmental behaviors. Specifically, when individuals identify with the organization where they work, they are more satisfied to be part of it and will therefore work towards achieving its greener goals, as well as being more likely to voluntarily act in a more sustainable manner.

An organization that adopts green HRM practices is sending a clear message to the employees that it is committed to the social green cause [8,38], creating a sense of pride in the organization and, consequently, an emotional attachment to the organization [60]. Therefore, the social identity theory would suggest that perceived GHRM can be positively related to employees’ organizational identification [38] and, in turn, positive employee workplace outcomes, such as employees’ eco-friendly behavior.

These discussions provide an empirical and theoretical rationale for the mediating role of organizational identification in the relationship between perceived GHRM and employees’ eco-friendly behavior.

These paths can create a competitive edge in organizations that intend to support the sustainability cause, as the effects of pro-environmental behavior among employees as well as employees’ sense of organizational identification can provide benefits that are relevant to the urgent need to integrate sustainability into the objectives of the organizations’ HRM systems [48]. Therefore, it is proposed that GHRM practices increase organizational identification, which, in turn, will improve employees’ eco-friendly behavior, in line with Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Organizational identification mediates the relationship between GHRM and employees’ eco-friendly behavior.

The proposed conceptual research model is as follows (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Conceptual research model.

3. Method

3.1. Procedure and Sample

As a criterion for the pursuit of the study’s objectives, we opted to consider the tourism sector for our convenience sample, due to the relevance that this business sector has for the Portuguese economy. To test the research hypotheses, a self-report survey was applied to a convenience sample of employees who have worked in the tourism sector in Portugal for at least 6 months, the time necessary to have a reliable notion of organizational reality [1]. Information about the objectives of the survey, data confidentiality and respondents’ anonymity, and informed consent was provided in the questionnaire. The respondents were also encouraged to give honest answers. The survey was sent by e-mail to people working in different tourism organizations in Portugal, and the data were collected between July 2021 and January 2022.

The final sample included 235 employees from various tourism organizations. The gender distribution was slightly biased towards female respondents (66.4%), and a little less than half (46.0%) of respondents were 39–54 years old, while around 44.3% of the respondents were 22–38 years old. Regarding the level of education, 58.7% had a higher education degree. Regarding job seniority, 37.0% of the respondents have been employed in their organization for 1 to 5 years, 25.5% for 6 to 10 years and 24.7% for more than 15 years.

3.2. Measures

The items were translated from English into Portuguese by one translator and then independently back-translated into English by another translator [61]. The translators discussed any discrepancies between the original and back-translated versions.

GHRM was evaluated by six items of Kim et al.’s [10] study based on the CSR HRM scale of Shen and Benson [62] and on the scale of education from the environmental management system (EMS) developed by Hsiao et al. [63]. Using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Never”; 5 = “Always”), employees were asked to indicate to what extent they agreed with each statement presented. Sample items included “My organization provides adequate training to promote environmental management as a core organizational value”, “My organization considers how well employee is doing at being eco-friendly as part of their performance appraisals” and “My organization links employees’ eco-friendly behavior to rewards and compensation”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93.

To measure the employees’ eco-friendly behavior, an instrument from Kim et al.’s [10] study was used, consisting of 7 items. Sample items included “I conserve materials at work” and “I pay close attention to water leaks”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.76. Using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly disagree”; 5 = “Strongly agree”), employees were asked to indicate to what extent they agreed with each statement presented.

Organizational identification was measured through 3 items proposed and validated by Kim et al. [64]. Sample items included: “I feel strong ties with my company” and “I am part of my company”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96. Individuals were asked to report the degree to which each of the three statements applied to them, using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Never”; 5 = “Always”).

4. Results

Prior to the detailed and forthcoming treatment of the data, we opted to perform the Harman test as a cautionary measure to test for common method bias in our data. According to the best recommendations of Podsakoff et al. [65], if a significant amount of common method bias exists in the data, then a factorial analysis (unrotated solution) of all variables contained in the model of analysis will generate a single factor accounting for most of the variance. Our results showed that the data were robust to common method bias.

After this procedure, we analyzed the data presented in the correlation matrix (Table 1), in which it is possible to see how the study variables are associated with each other. GHRM is positively and significantly correlated with employees’ eco-friendly behavior (r = 0.300; sig. ≤ 0.01) and with organizational identification (r = 0.534; sig. ≤ 0.01). Similarly, employees’ eco-friendly behavior and organizational identification are also positively and significantly correlated (r = 0.337; sig. ≤ 0.01). Regarding the demographic variables and their correlation with the composite variables, hierarchical position is significantly and positively correlated with GHRM (r = 0.199; sig. ≤ 0.01), as well as with employees’ eco-friendly behavior (r = 0.175; sig. ≤ 0.01) and with organizational identification (r = 0.360; sig. ≤ 0.01). The remaining demographic variables did not show any significant correlation with the composite variables of the study.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix (N = 235).

These initial results seem to imply that the GHRM orientations of an organization positively influence the shaping of the eco-friendly behavior of the workers, as well as their identification with the organization. Likewise, the identification of the workers with the organization is also positively associated with the adoption of eco-friendly behavior. Thus, when jointly analyzed together, these initial results seem to support the idea that the higher the visibility of GHRM policies and practices, the stronger the organizational identification and higher the adoption of workers’ eco-friendly behavior. Moreover, the correlation between organizational identification and employees’ eco-friendly behaviors seems to support the idea that the higher the workers’ organizational identification, the higher the likeliness of workers’ adoption of eco-friendly behaviors. These results seem to support both Hypotheses 1 and 2 of the study.

To investigate the mediation effect predicted in Hypothesis 3, foreseeing the existence of a mediating effect by organizational identification in the relationship between GHRM and employees’ eco-friendly behavior, the methodological procedure proposed by Baron and Kenny [66] was followed. According to these authors, for mediation effects to be tested, the following regression equations should be estimated: (1) regression of the mediator variable on the predictor variable, (2) regression of the criterion variable on the predictor variable and (3) regression of the criterion variable on the predictor variable, controlling for the mediator variable.

The authors further explained that for a mediation effect to be verified, the following conditions must be satisfied: (1) the predictor variable must affect the mediating variable in the first regression equation, (2) the predictor variable must be affected by the criterion variable in the second equation and (3) the mediating variable must affect the criterion variable in the third equation. When confirming these conditions, we may be facing partial mediation or a total mediation if the effect of the predictor on the dependent variable remains significant (or not) in the presence of the mediating variable in the equation. Partial mediation is verified when the effect of the predictor variable on the criterion variable in the third equation is smaller than in the second equation, whereas total mediation is verified when the effect of the predictor variable on the criterion variable in the third equation is no longer meaningful [66].

Within the methodology applied in the present study, the first equation evaluated the effect of GHRM on organizational identification (β = 0.448; sig. ≤ 0.01; t = 9.263), with a significant and positive relationship. The second equation was intended to verify the effect of GHRM on employees’ eco-friendly behavior (β = 0.128; sig. ≤ 0.01; t = 4.334), and the third equation added the mediating variable, organizational identification, in the analysis model (β = 0.115; sig. ≤ 0.01; t = 2.871). In Table 2, it was possible to verify that when the mediating variable was jointly predicted in the estimated regression, the relationship between GHRM and employees’ eco-friendly behavior remained significant (β = 0.128; sig. ≤ 0.01; t = 4.334/β = 0.077; sig. ≥ 0.05; t = 2.255), and the effect of GHRM on the employees’ eco-friendly behavior in the third equation was smaller than in the second equation (R2 adjust. = 0.116). These results support the assumption of the existence of a partial mediation effect of organizational identification on the relationship between GHRM and employees’ eco-friendly behavior. All steps of the methodological procedure were made with the inclusion of control variables that seemed relevant for integration into the scope of the study, such as workers’ seniority, hierarchical position, education and gender.

Table 2.

Regression table.

In order to add additional evidence and discussion to our results, we opted to perform a supplementary mediation test using Sobel’s test [67], which proposes the following equation for estimating indirect effects, such as the one foreseen in Hypothesis 3: Z-value= a*b/SQRT(b2*sa2 + a2*sb2). This test should be seen as complementary to the methodology carried out by Baron and Kenny [66], by permitting a more direct evaluation of the existence of indirect effects, as Sobel test is indicated as a more restrictive test. In our study, the Sobel test value was Z = 4.22288273/p = 0.001, thus confirming the existence of a mediation effect of organizational identification on the relationship between GHRM and employees’ eco-friendly behavior.

5. Discussion

This study sought to examine the impact of the GHRM on employees’ eco-friendly behaviors, as well as the mediating role of organizational identification in the relationship between GHRM and employees’ eco-friendly behaviors in the Portuguese tourism industry.

According to the results, we can conclude that GHRM seems to be a resourceful and structured way of enhancing both the identification of the workers with the organization, as well as the adoption of eco-friendly behaviors. We can conclude on this finding on the basis of both the correlation between the study variables, and the regression equations estimated. In accordance, the way organizations develop internal HRM procedures in alignment with GHRM orientations has, in fact, a positive impact on workers’ identification and bonding with the organization, as well as with the adoption of relevant environment protection behaviors. These findings are consistent with prior research that found a relationship between GHRM and organizational identification [12,22,68]. In the same way, green HRM practices can make employees more psychologically available to engage in green behaviors [16,49,50].

Furthermore, the study results also seem to indicate that GHRM policies and practices should be seen as a powerful tool for developing a distal process regarding workers’ attitudes and behavior adoption activation. Based on our findings, GHRM has demonstrated the ability of activating a process leading to workers’ adoption of eco-friendly behavior directly, and also through organizational identification, working, in this case, as a significant mediator variable, making this distal process viable. It seems that when an organization strategically chooses to adopt green HRM policies and practices, it will likely enhance both workers’ organizational identification and the adoption of environmental pro-action behaviors directly, as well as employees’ eco-friendly behaviors through the effect of organizational identification as a mediator variable. GHRM seems to be advisable as a viable way of aligning workers’ attitudes and behaviors regarding environmental protection orientations [10]. This study has used social identity theory [12] to rationalize the positive interpretations that employees have of perceived green HRM practices, which lead to employee organizational identification and, consequently, employees’ eco-friendly behaviors.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions and Implications of the Study

This study arises from the attempt to fill the gap in the literature on GHRM, and aimed to support a change in organizational mindsets and values concerning the environment [69], thus providing important contributions within the scope of the application of GHRM practices and their effects on the environment [10,70,71] and organizations, particularly in the tourism sector in Portugal.

First, our research contributes to a greater understanding of the approaches of workers in the Portuguese tourism industry towards GHRM, namely, organizational identification and employees’ eco-friendly behaviors related to energy usage, water usage and waste reduction, which are suitable in the hotel context [10]. The results suggest that organizations applying greener HRM that respects human beings and the environment might positively influence the attitudes and behaviors of their employees, and thus contribute positively to the organization and to society.

Second, through this study it is possible to understand how employees’ affective attachment to and identification with the organization can intensify the impact of GHRM practices on their green behaviors.

Third, we contribute to the limited body of knowledge on GHRM in the tertiary or service sector [72] and especially in the tourism industry. Fourth, unlike the deep literature on GHRM that links human resource practices to workers’ more positive work-related behaviors and outcomes, this study extends the effects of GHRM to HRM, as well as its impact on workers’ green behaviors [73].

Furthermore, the results of this study are also relevant for managers, as they provide a more comprehensive understanding of some of the organizational aspects that contribute to enhancing employees’ sense of belonging and identification with the organization, increasing their green behaviors and improving the organization’s outcomes. However, the effects of GHRM policies can only be effective and provide sustainable competitive advantages for the development and evolution of the company if they are well accepted by employees, especially by those who are aligned with the objectives of the organization [74]. Thus, the action of organizations should start by investing in leaders with a greener mindset, who believe in the transparency of processes, the need for good interpersonal relationships, good communication and the importance of meeting the socio-emotional needs of employees.

In turn, managers’ actions, should involve implementing hiring and recruitment policies with a preference for green-conscious candidates; designing and implementing green training programs, such as waste management or waste reduction, to motivate employees and increase their cognitive and emotional readiness to serve the organization’s green policies [75]; and valuing their employees’ green contributions, giving them positive feedback and making them feel that their environmental interests are taken into account to better engage employees in the organizations’ green initiatives, as well as to ensure the successful application of GHRM practices [73].

Effective implementation of GHRM guided by green organizational policies will have the ability to improve employees’ green outcomes and, potentially, to contribute to enhancing their organizational motivation and identification. Thus, GHRM should be implemented not only to achieve green goals but also to encourage green behaviors among employees and within the organization, as only then will it be possible for business and society to achieve sustainable development goals and make a better world.

6.2. Study Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

Paulet et al. [76] revealed an expressive interest in GHRM research, as it can provide important tools and guidelines to HRM managers to be incorporated into the organizations’ processes, strategies and structures. In this sense, the model proposed by this study required an in-depth analysis to achieve its main objectives; in turn, this dedication resulted in some limitations, namely the need to analyze the impact of HRM on other psychosocial variables, such as internal communication.

Although the sample size was satisfactory, convenience sampling is another limitation in this study that did not involve any probabilistic sample, which restricted the generalizability of the results. The application of cross-sectional data did not allow conclusions to be drawn about the causal link between the variables, another obvious limitation.

Following a methodology in which data were collected over a certain period and through the same source raises the risk of introducing common method variance [68]. To address this concern, some preventative methods were undertaken, such as the Harman test. Considering this, the authors suggest the application of a more comprehensive longitudinal investigation to generate more valid conclusions regarding causality. Although this research has limitations, it was able to enrich the literature on the positive impacts of GHRM for the implementation of strategies that enable tourism sector organizations to achieve a competitive difference.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R.; methodology, N.R., G.P.G. and D.R.G.; software, N.R. and D.R.G.; formal analysis, A.S.S.; data collection, E.O.; writing—original draft preparation, N.R., G.P.G. and E.O.; writing—review and editing, D.R.G. and A.S.S.; supervision, N.R.; funding acquisition, D.R.G. and N.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal (Grants UIDB/05021/2020 and UIDB/04928/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the respondents of the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ribeiro, N.; Duarte, P.; Fidalgo, J. Authentic leadership’s effect on customer orientation and turnover intention among Portuguese hospitality employees: The mediating role of affective commitment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2097–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderwood, L.U.; Maksim, S. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019 Travel and Tourism at a Tipping Point. World Economic Forum’s Platform. 2019. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TTCR_2019.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Turismo de Portugal Melhor Organismo Oficial de Turismo Da Europa Pela Sexta Vez Nos World Travel Awards 2019. [Tourism of Portugal Best Official Tourism Organization in Europe for the Sixth Time in World Travel Awards 2019]; Turismo de Portugal: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019.

- Costa, J.; Montenegro, M.; Gomes, J. Sustainability as a measure of tourism success: The Portuguese Promotional Tourism Boards’ view. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2022, 14, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintassilgo, P.; Rossello, J.; Santana-Gallego, M.; Valle, E. The economic dimension of climate change impacts on tourism: The case of Portugal. Tour. Econ. 2016, 22, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Muller-Camen, M.; Redman, T.; Wilkinson, A. Contemporary developments in Green (environmental) HRM scholarship. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 27, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yusoff, Y.M.; Nejati, M.; Kee, D.M.H.; Amran, A. Linking Green Human Resource Management Practices to Environmental Performance in Hotel Industry. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albertini, E. Does Environmental Management Improve Financial Performance? A Meta-Analytical Review. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M.; Phetvaroon, K. The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Meija-Morelos, J.H. Organisational support is not always enough to encourage employee environmental performance. The moderating role of exchange ideology. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Dumont, J.; Deng, X. Employee perceptions of green HRM and non-green employee work outcomes: The social identity and stakeholder perspectives. Group Organ. Manag. 2018, 43, 594–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.N.; Tučková, Z.; Phan, Q. Greening human resource management and employee commitment towards the environment: An interaction model. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2019, 20, 446–465. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donohue, W.; Torugsa, N. The moderating effect of ‘Green’ HRM on the association between proactive environmental management and financial performance in small firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 769–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, S.; Ananthram, S.; Chan, C.; Brown, K. Green office buildings and sustainability: Does green human resource management elicit green Behaviours? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 329, 129764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishmotevali, M.; Altinay, L. Toward pro-environmental performance in the hospitality industry: Empirical evidence on the mediating and interaction analysis. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 1–27, Ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A.; Nagano, M.S. Contributions of HRM throughout the stages of environmental management: Methodological triangulation applied to companies in Brazil. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1049–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Rabiei, S.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Envisioning the invisible: Understanding the synergy between green human resource management and green supply chain management in manufacturing firms in Iran in light of the moderating effect of employees’ resistance to change. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K. Environmental strategies and human resource development consistency: Research in the manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Jiang, K.; Tang, G. Leveraging green HRM for firm performance: The joint effects of CEO environmental belief and external pollution severity and the mediating role of employee environmental commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 61, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyambalapitiya, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X. Green human resource management: A proposed model in the context of Sri Lanka’s tourism industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C. Environmental training and environmental management maturity of Brazilian companies with ISO14001: Empirical evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 96, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, V.D. Corporate Environmental Strategy: Theoretical, Practical, and Ethical Aspects; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 2nd ed.; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson-Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1985; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S. Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidts, A.; Pruyn, A.T.H.; Van Riel, C.B. The impact of employee communication and perceived external prestige on organizational identification. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, C.; de Winne, S.; Sels, L. The influence of line managers and HR department on employees’ affective commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 1618–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G.E.; Ashforth, B.E. Evidence toward an expanded model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythreatis, S.; Mostafa, A.M.S.; Pereira, V.; Wang, X.; Del Giudice, M. Servant leadership, CSR perceptions, moral meaningfulness and organizational identification-evidence from the Middle East. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudêncio, P.; Coelho, A.; Ribeiro, N. The Role of Trust in Corporate Social Responsibility and Worker Relationships. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudêncio, P.; Coelho, A.; Ribeiro, N. The impact of CSR perceptions on workers turnover intentions: Exploring supervisor exchange process and the role of perceived external prestige. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 17, 543–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.A.; Cheema, S.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Ali, M.; Rafiq, N. Perceived corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental Behaviours: The role of organizational identification and coworker pro-environmental advocacy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rangarajan, N.; Rahm, D. Greening human resources: A survey of city-level initiatives. Rev. Public Pers. Admin. 2011, 31, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegge, J.; Van Dick, R.; Fisher, G.K.; Wecking, C.; Moltzen, K. Work motivation, organisational identification, and well-being in call centre work. Work Stress 2006, 20, 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abimbola, T.; Vallaster, C. Brand, organisational identity and reputation in SMEs: An overview. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2007, 10, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, C.L.; Dubois, D.A. Strategic HRM as social design for environmental sustainability in organization. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 799–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Nájera, M.; Rivera-Martínez, J.G.; Hafkamp, W.A. An explorative socio-psychological model for determining sustainable Behaviour: Pilot study in German and Mexican Universities. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, K.L.; Dmitrieva, A.; Adriasola, E. Changing behaviour: Increasing the effectiveness of workplace interventions in creating pro-environmental behaviour change. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee green behavior: A theoretical framework, multilevel review, and future research agenda. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, W.C.; Motowidlo, S.J. Task performance and contextual performance: The meaning for personnel selection research. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Green Human Resource Management and Employee Green Behaviour: An Empirical Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.; Ahmad, B.; Kazmi, S. The effect of green human resource management on environmental performance: The mediating role of employee eco-friendly behavior. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L.H.; Lepak, D.P.; Schneider, B. Employee attributions of the “why” of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 503–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saeed, B.B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawang, S.; Kivits, R.A. Greener workplace: Understanding senior management’s adoption decisions through the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russell, S.; Griffiths, A. The role of emotions in driving workplace pro-environmental behaviors. Res. Emot. Organ. 2008, 4, 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, C.; Chatman, J. Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial Behaviour. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A.; Pratt, M.G.; Whetten, D.A. Identity, intended image, construed image, and reputation: An interdisciplinary framework and suggested terminology. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Chen, Y.S. Green organizational identity and green innovation. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1056–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkorezis, P.; Petridou, E. Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behaviour: Organisational identification as a mediator. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2017, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Yang, Y.C. Factors influencing green organizational citizenship behavior. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2020, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, E.L. Planning for climate change in small islands: Insights from national hurricane preparedness in the Cayman Islands. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2005, 15, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work Behaviour. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1723–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, T.Y.; Chuang, C.M.; Kuo, N.W.; Yu, S.M.F. Establishing attributes of an environmental management system for green hotel evaluation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.T.; Kim, N.M. Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, M.E. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol. Methodol. 1982, 13, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, M.R.B.; Kee, D.M.H.; Rimi, N.N. The influence of green HRM practices on green service Behaviours: The mediating effect of green knowledge sharing. Empl. Relat. 2021, 43, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C. Environmental training in organizations: From a literature review to a framework for future research. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 74, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Umrani, W.A. The impact of ethical leadership style on job satisfaction: Mediating role of perception of green HRM and psychological safety. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Ullah, K.; Khan, A. The impact of green HRM on green creativity: Mediating role of pro-environmental Behaviours and moderating role of ethical leadership style. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 1–33, Ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Thanh, T.V.; Tučková, Z.; Thuy, V.T.N. The role of green human resource management in driving hotel’s environmental performance: Interaction and mediation analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Kundi, Y.M.; Becker, A. Green human resource management in nonprofit organizations: Effects on employee green behavior and the role of perceived green organizational support. Pers. Rev. 2021. Ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Dahleez, K.A.; Farao, C.; Alshurafa, M. Performance measurement and NPOs’ effectiveness: Does internal stakeholders’ trust matter? Evidence from Palestine. Benchmarking 2020, 28, 2580–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Valdivia, I.; Llorens-Montes, F.J.; Ruiz-Moreno, A. Achieving engagement among hospitality employees: A serial mediation model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulet, R.; Holland, P.; Morgan, D. Invited Review Article A meta-review of 10 years of green human resource management: Is Green HRM headed towards a roadblock or a revitalisation? Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2021, 59, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).