Abstract

The use of prohibited performance-enhancing substances (PES) in fitness and gym settings is a public health concern as knowledge concerning its short-term and long-term adverse health consequences is emerging. Understanding the underlying psychosocial mechanisms of PES use and the characteristics of the gym-goers who use PES could help identify those who are most vulnerable to PES use. The aim of this study was to investigate the profile (e.g., sociodemographic factors, exercise profile, gym modalities, peers, and social influence) and psychosocial determinants (e.g., attitudes, subjective norms, beliefs, and intentions) of PES users in gym and fitness contexts. In total, 453 gym-goers (mean age = 35.64 years; SD = 13.08) completed an online survey. Neural networks showed a global profile of PES users characterized by a desire to increase muscle mass, shape their body, and improve physical condition; being advised by friends, training colleagues and coaches or on the Internet; less formal education, and more positive beliefs for PES use. These results may support public health and clinical interventions to prevent abusive use of PES and improve the health and well-being of gym-goers.

1. Introduction

The existing literature is clear about the various reasons that lead individuals to engage in physical activity (PA) [1]. In addition, expected benefits of PA participation include reasons such as obtaining a leaner or more muscular body. However, studies indicate that one in eight fitness participants consider using illicit substances to attain an aesthetic ideal body or to boost their physical performance [2,3].

A Performance Enhancing-Substance (PES) is any substance used in non-pharmacologic doses aimed at increasing sports performance and physical conditioning [4]. Among these substances are those that cause changes in behavior, arousal, and/or pain perception, such as stimulants, anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS), erythropoietin, human growth hormones, or diuretics [4].

Nowadays, the increased PES use in fitness and strength and conditioning environments, especially AAS, has important public health implications; although knowledge concerning PES’s short-term negative consequences on health are not new [5,6], obvious long-term health effects are only now emerging [7,8,9]. PES is frequently used without medical or nutritional support, suggesting that their use is accompanied by a lack of awareness of the likely perils typically associated with the unregulated consumption of prohibited or untested substances [3].

Bodybuilders and gym users have the highest prevalence rates for PES [10]. A recent study [11] showed that 11.1% of Portuguese gym-goers declared PES use and 5.3% considered using them soon. As such, this group is at a particularly high-risk for PES use as this behavior is okay and normalized by those within the gym environment [10]. The same study [11] showed that PES use changes considerably as a function of demographic variables (e.g., education, gender) and practice-related variables (e.g., gym modality, exercise profile). Adult men with a lower educational level, who do bodybuilding and practice frequently, are prone to the use of prohibited PES. However, according to Backhouse et al. [10], users do not always fit the same profile, which implies the need for further investigation on the characteristics of gym users’ PES. This information may be utilized to develop effective educational campaigns aimed at reducing this behavior.

Furthermore, PES use has been related to other variables in doping research. Studies with gym-goers and competitive athletes indicated that past or current behavioral choices determine intentions and future PES use [12,13,14,15]. Indeed, studies demonstrated that gym users who are familiar with, or are already users of, PES have more positive attitudes towards PES use and higher risk of recurrent use [15,16].

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) has been the framework of choice in doping behavior research in sport to analyze the psycho-social processes that constitute the antecedents of PES use [17,18,19]. In brief, the model suggests that the behavioral intentions toward a health behavior [20] is regulated by the individuals’ attitudes toward the behavior, their subjective norms, and their perceived behavioral control. Specifically, (i) attitudes toward the behavior reflect “the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation or appraisal of the behavior in question; (ii) subjective norms refer to the perceived social pressure to whether or not perform the behavior; and (iii) perceived behavior control refers to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior and it is assumed to reflect past experience as well as anticipated impediments and obstacles” [20] (p. 188). Behavioral intentions are the strongest predictor of the behavior, although perceived behavioral control can directly predict behavior when it is perceived to be outside one’s volitional control.

The effectiveness of TPB variables in predicting PES use intentions was supported in a recent study investigating the PES use in fitness/gym context [21]. Therefore, this theory explains PES use by hypothesizing that users show more favorable beliefs, subjective norms, attitudes, and intention to PES use than nonusers [15,16]. Moreover, it guides the development of strategies to prevent this behavior.

According to Whitaker, Long, Petróczi and Backhouse [22], effective prevention strategies should rely on individually tailored approaches. To reach these goals, it is necessary to identify the underlying psychosocial mechanisms of PES use and the profile of the gym users who are most vulnerable to PES use. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify the joint characteristics (e.g., sociodemographic factors, exercise profile, gym modalities, peers, and social influence) and psychosocial determinants (e.g., attitudes, subjective norms, beliefs, and intentions) of PES users in a gym/fitness context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

An a priori sample size calculation was undertaken to identify an appropriate sample size [23]. It was determined that 434 participants were required to obtain a power analysis of 0.9 for an anticipated effect size of 0.2 with a probability level of 0.05. Therefore, a sample of 453 participants (mean age = 35.64 years; SD = 13.08; % females = 61.1; % males = 38.6) was recruited.

Participants were recruited by directly contacting gyms and fitness centers by e-mail and Facebook.

Once prospective participants were identified, a web link with to an informed consent page, where a participant information sheet contained detailed information concerning the study, was sent to the survey participants. In addition, ethical matters were addressed, including anonymity, confidentiality and the right to withdraw. Participants provided informed consent by acknowledging understanding of the information and stating agreement with the participation. The questionnaire was then accessed and a web-based survey was administered via REDCap software (Version 5.11.4, Vanderbilt University). The survey took approximately 15 min to complete.

Data collection took place between October and November 2017. Data were anonymized at the point of data collection and encryption procedures during data transfer were employed. Variables assessed included (1) demographic data, (2) self-reported use of PES (doping behavior), and (3) attitudes, subjective norms, beliefs, and PES use intention.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Human Kinetics of the University of Lisbon (study protocol no. 38/2017).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics, Exercise Profile, Gym Modalities, Peers, Social Influence of PES Use and Self-Reported Use of PES

The first section of the questionnaire [11] measured general information such as demographic, (i.e., age, gender, education level, marital status, occupation), training schedule characteristics and participation on competitive sport. The second section addressed the use of PES by self-report based on the WADA prohibited substance list (2017) (type/name, length of use, location of purchase, reason for use, ways of administration, and possible adverse effects). Finally, other substance consumption behaviors were also measured by self-report, specifically, a history of smoking and alcohol use.

To measure PES use, participants answered “yes” or “no” to the following question: “As part of your practice, have you ever taken performance-enhancing substances?” Participants were classified into two groups: (a) no experience of PES use and (b) past or current experience of PES use. This classification determined participants’ risk of PES [24]. The WADA Prohibited List was followed as a criterion for the identification of PES; hence, vitamins and dietary supplements were not deemed to be performance enhancement substances. Questions related to a history of smoking and alcohol use are not included in the present study.

2.2.2. Questionnaire of Attitudes towards Doping in Fitness (QAD-Fit)

Attitudes, subjective norms, beliefs, and PES use intention were measured through the QAD-Fit [25]. This instrument was composed of 16 items that measure four dimensions of the TPB: attitudes (five items; e.g., “Selling PES should be punished”), subjective norms (three items; e.g., “I would take PES, if most people I know approved of it”), beliefs (three items; e.g., “Performance enhancing substances help to improve physical abilities”) and intention (five items; e.g., “I would take PES to achieve my goals in the practice of physical activity”). The score for each dimension was calculated by the mean of its items. These were answered on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1) totally disagree to (7) totally agree (see Supplementary Materials). QAD-Fit is a psychometrically valid instrument for Portuguese gym/fitness users. The total composite reliability (CR) was 0.85, with values of 0.74 for beliefs, 0.84 for attitudes, 0.86 for subjective norms and 0.97 for intentions [25].

2.3. Processing and Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, V.26 for Windows) was used for data analysis. To assess the importance of sociodemographic factors, exercise profile, gym modalities, peers and social sources, and psychosocial determinants in PES use, neural networks were used with multilayer perceptron, where 70% of the sample was considered for training (which allows training a neural network from a set of data with known output values) and 30% for testing (which allows the assessment of the performance of the trained network in predicting the output values) [26,27,28,29]. As outputs, tables are presented with the importance and normalized importance of the independent variables for the prediction of the dependent variable, PES use (yes/no). The percentage of incorrect predictions in the test phase tends to be higher than in the training phase because 70% of the sample is present in the latter. The most important independent variable receives a percentage of 100 and the remaining ones receive a percentage proportional to their importance. To identify the trend of associations between the categories of independent variables with the dependent variable (use of PES/no use of PES), i.e., to study the profile of PES users, multiple correspondence analysis was utilized. This process is especially suitable for describing matrices with a large volume of discrete data and without a clearly defined a priori structure. Multiple correspondence analysis is used to explore the relationships of three or more categorical variables [30,31,32,33].

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

A convenience sample of 453 Portuguese gym/fitness center users (age range = 16–79 years; mean age = 35.64 years; SD = 13.08) participated in this research. Of all participants, 277 were females (61.1%), 175 were males (38.6%), and one did not respond (0.3%). Participants were involved in several gym activities (e.g., 57% cardio fitness, 56.5% bodybuilding, 27.8% stretching, 27.2% localized), 11.1% of which (n = 50) used PES at the time.

Considering the sociodemographic characteristics, the most important factor (that is, what contributes most) to the use of PES (yes/no) is occupation, followed by gender and education (Table 1). The model presented revealed 11.8% incorrect predictions in the neural network training phase and 8.7% in the test phase.

Table 1.

Importance and normalized importance of the sociodemographic characteristics for the use of PES.

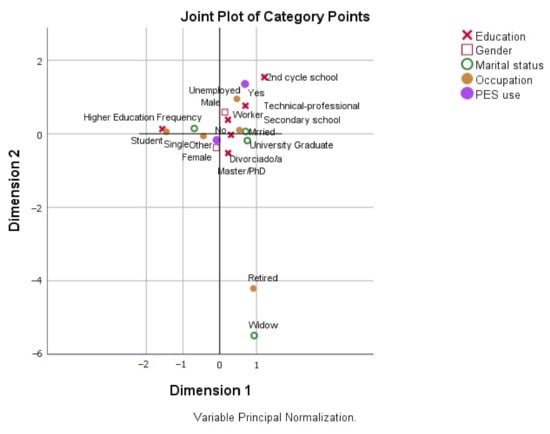

Figure 1 illustrates the results of the profile analysis of PES users. It can be observed that men, low education, and unemployed are the categories of independent variables closest to the “yes” category of PES use, suggesting that these are the characteristics of individuals who use PES.

Figure 1.

Profile of PES users, regarding sociodemographic characteristics.

3.2. Exercise Profile and Gym Modalities

Regarding the exercise profile and gym modalities, the most important factor for the use of PES was the frequency of training, followed by bodybuilding (Table 2). The percentage of incorrect predictions was 11% for the neural network training phase and 11.8% for the test phase.

Table 2.

Importance and normalized importance of the profile of training and gym modalities practiced.

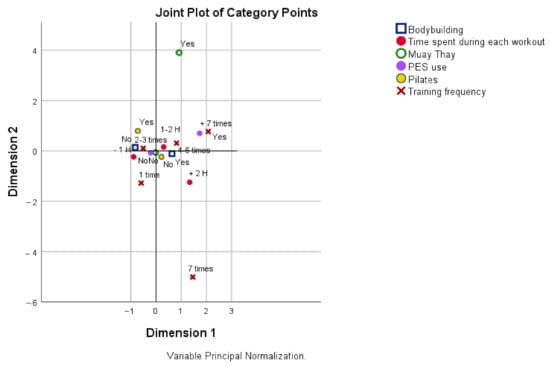

Figure 2 identifies the trend of association between the categories of independent variables with the use of PES or not through the analysis of the training profile and the modalities practiced. PES users tend to train more frequently and practice bodybuilding, as these are the categories of independent variables closest to the “yes” category of PES use.

Figure 2.

Profile of PES users, in relation to the profile of training and gym modalities practiced.

3.3. Peers and Social Influence of PES Use

Concerning the importance of the sources sought for advice concerning the use of doping (yes/no), it was found that friends are the most important factor, followed by the Internet and the coach (Table 3). The model showed 7.4% of incorrect predictions in the neural network training phase and 10.2% in the test phase.

Table 3.

Importance and normalized importance of the profile of those who advise to use PES.

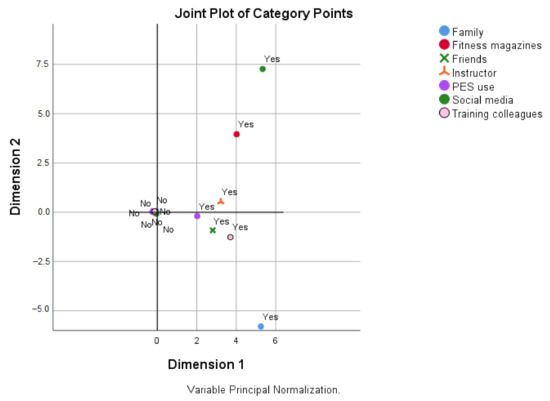

Identifying the trend of association between the categories of independent variables with the use of PES or not, through the analysis of the profile of PES users, suggests that their friends, instructors, and training colleagues are the most important social influences who advised them to use these substances since these are the categories of independent variables closest to the “yes” category of PES use (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Profile of PES users, in relation to who advises them on taking these substances.

Regarding the reasons for PES use, the most important factors were to improve physical condition, followed by reaching a specific goal, increasing performance, and increasing muscle or body shaping (Table 4). In the neural network training phase, 1.6% of incorrect predictions were detected while in the test phase this value increased to 3.6%.

Table 4.

Importance and normalized importance of the reasons for PES use.

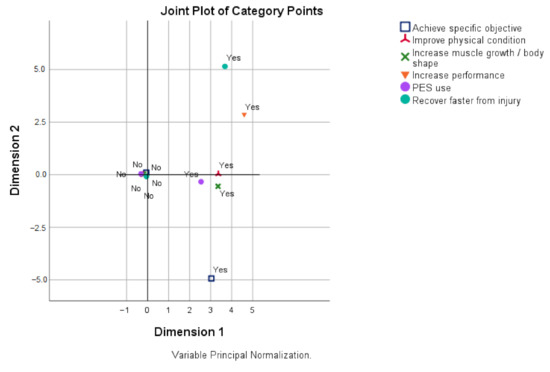

As for the association trend between the categories of independent variables and the use of PES, concerning the reasons to take these substances, the profile of PES users suggests that consumption is motivated by a desire to improve their physical condition and increase muscle mass or shape the body, as they are the categories of independent variables closest to the “yes” category of PES use (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Profile of PES users, regarding the reasons that lead to PES use.

3.4. Psychosocial Determinants

Concerning the psychosocial determinants, behavioral intentions were the most important for the use of PES, followed by beliefs (Table 5). In the neural network training phase, 8.1% of incorrect predictions were detected while in the test phase this value increased to 11.8%.

Table 5.

Importance and normalized importance of the psychological factors for PES use.

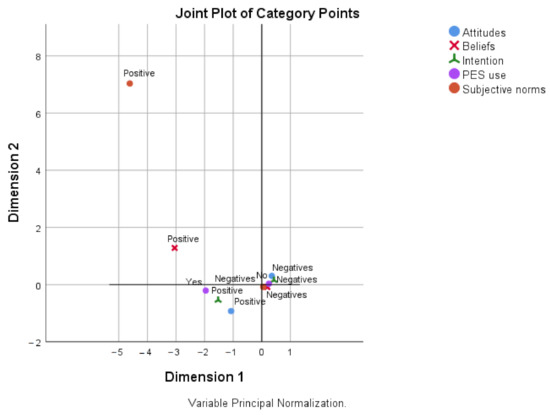

In relation to the psychosocial determinants, PES users are individuals with a positive intention to take PES (score ≥ 3.5) and a positive attitude towards taking PES (score ≥ 3.5). However, the profile also includes individuals with positive beliefs for taking these substances (score ≥ 3.5), as these are the categories of independent variables closest to the “yes” category of PES use (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Profile of PES users, regarding psychosocial determinants.

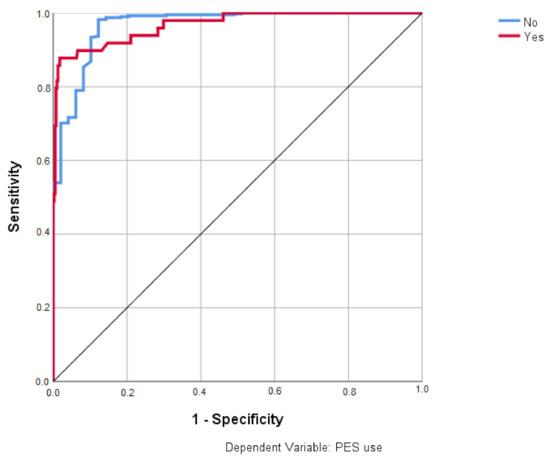

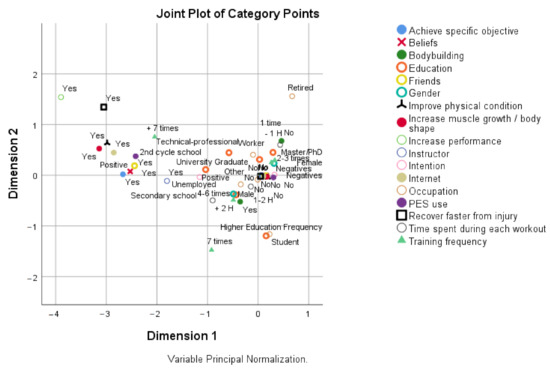

3.5. Global Profile of PES Users

To obtain a global model which better characterizes PES users’ profile, several models were built. The model that presented the best precision and that best discriminated PES users from non-users was based on the models previously obtained, where those variables that had a normalized importance greater than 50% were considered as independent variables. The model presented revealed 2.6% of incorrect predictions in the training phase and 5.0% in the test phase of the neural network analysis. The obtained global model has an excellent discriminatory capacity between PES users and non-users (Figure 6). The model has excellent specificity and sensitivity and the area under the ROC curve for PES users and for non-PES users is 0.967 for both, which means that 96.7% of cases are well discriminated. Table 6 shows that the most important factors for PES use are to improve physical condition, increase muscle growth/body shape, and achieve a specific objective.

Figure 6.

ROC curve for analyzing the sensitivity and specificity of the model and its discriminatory capacity.

Table 6.

Importance and normalized importance of the sociodemographic factors, exercise profile, gym modalities, peers and social sources, and psychosocial determinants for PES use.

Figure 7 illustrates the global profile of PES users, which allows for joint identification of the tendency of association between the categories of the independent variables with the categories of the dependent variable, by analyzing the points closest to the “yes” category of PES use. PES users are those who want to achieve a specific objective, increase muscle mass/shape the body, improve their physical condition, increase performance, recover faster from injury, train more frequently, are advised by friends or influenced by information on the Internet, and have lower education attainment and higher positive beliefs and intention for PES use. This general profile of PES users shows that the association between factors and use of PES has changed because the combination of all factors alters their importance.

Figure 7.

Global profile of PES users, in relation to sociodemographic factors, modalities and training profile, who advises, reasons, and psychological factors.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated gym goers’ characteristics and psychosocial determinants toward PES use in a gym/fitness context. Several characteristics were identified as important factors that contribute to this behavior, suggesting a profile of PES users. The most important sociodemographic characteristic associated with the use of PES was occupation, followed by gender and education, translating into a profile compatible with being a male participant with low education and being unemployed. This finding is consistent with other studies as males tend to be more susceptible toward PES use, and therefore are at greater risk than females [10,19,34]. According to Leite, et al. [35] gender differences can be explained by the different values males and females place on muscularity; while a muscular body is judged as undesirable by females, having large muscles represents a desirable aesthetic standard for males.

On the other hand, a low education level could make individuals less conscious of the negative implications of PES use, leading to the use of such substances. Moreover, lower educational levels are linked to less differentiated body image valuations and more subject to stereotypes about masculinity, showing that individuals with lower levels of education tend to use the gym for body building purposes, due to the overvaluation of the muscular dimension of the body [36].

Indeed, according to Eurostat [37] people with less education are also more prone to higher unemployment rates. However, this evidence of correlation does not mean causality. However, studies suggest an interconnection between unemployment and substance use [38,39]. Compared to employed individuals, the unemployed ones are more likely to use illicit and prescription drugs, and to have alcohol- and drug use-related disorders [38]. The reasons for the relationship between unemployment and substance abuse may be multi-faceted. In some cases, substance abuse can be the result of the immediate impact of unemployment, which can lead to financial instability, and in turn to addiction (e.g., illicit drugs, alcohol, gambling). Ultimately this process negatively affects the individual’s mental health. In other cases, those struggling with substance abuse may prioritize these substances over everything else in their lives, including their jobs [40].

Concerning exercise profile and gym modalities, results showed that the most important factor for the use of PES was the frequency of training and bodybuilding practice. This is not surprising as bodybuilders naturally know that the muscle hypertrophy they seek requires high training frequency alongside the help of “supplements”. However, according to Dores et al. [41], “excessive exercising” and “exercise addiction” [42] could be associated with appearance anxiety, low self-esteem, and the use of a variety of fitness supplements taken without medical consultation, which is a matter of increasing global concern [43]. Moreover, individuals who engaged in amateur bodybuilding tend to have higher rates of body dissatisfaction, such as muscle dysmorphia [43]. However, in the present study, these variables were not measured and, therefore, we cannot affirm that there is evidence of a relationship between the frequency of bodybuilding training and the addiction to exercise affecting PES use. Nevertheless, it seems that novices with this profile are more predisposed to taking greater risks. Future studies should explore this hypothesis.

Taking into consideration the importance of those who advise the use of PES, it was found that PES users tend to consult with friends, the Internet, and their instructors. According to Lima [44], in certain groups of peers (e.g., friends, gym colleagues, instructors), the pressure felt by group members can be so strong that it may lead to the anticipation of choices, reducing decisions to a status of quasi-routines. It should also be noted that the norms of a reference group (group to which an individual belongs or aspires to belong to) can also be very influential in determining attitudes and behaviors of its members [44]. Indeed, a sense of belonging and identification with a personally meaningful group involves the belief that one fits in the group, the expectation of being accepted by its members, and a willingness to make sacrifices for the sake of the group [45] (p. 10).

It was also found that the influence of the Internet as sources of “pressure” triggers promoting and reinforcing effects on attitudes and intentions towards the use of substances. Just as observed with females, the idealized male body portrayed in the media is increasingly unachievable, which also makes males vulnerable to the negative effects of media exposure [46]. Males taken from the general population who were exposed to tv ads that portrayed ideal bodies became significantly more depressed and dissatisfied with their muscular features than those who were exposed to neutral ads [47]. Moreover, in a sample of young male gym users, image-centric social media use was associated with the use of dietary supplements and anabolic androgenic steroids [48]. Considering that PES users engage in higher levels of physical activity to achieve the ideal body, and also present clinical and psychopathological features (e.g., substance abuse, body dysmorphic disorder) compared to non-users [49], social media may exert a significant attraction on these individuals to take these substances to improve their physical condition and increase their muscle mass or shape their body. These motives suggest that for these individuals, physical exercise is a vehicle to improve body-image in an attempt to improve well-being. The issue is that the ideal body image held is often unrealistic or requires extreme methods (hence the psychopathological profile of these individuals) [43].

The profile of PES users in relation to psychosocial determinants highlight the role of positive intention, attitude, and beliefs on PES use. Among the group of PES users, beliefs may be related with intentions to use PES; they believe that the use of PES, especially anabolic-androgenic steroids, will improve their appearance or enhance their physical abilities, (e.g., enhanced appearance, strength, performance) [50]. Indeed, studies using samples of gym users showed that individuals who are familiar with or are already users of PES tend to have more favorable attitudes towards PES use and higher risk of recurrent use [15,16]. As stated by Lazuras et al. [14], the use of PES leads to the development of more favorable attitudes towards PES use, as well as to a stronger wish for approval of PES use under specific circumstances (e.g., beliefs about performance improvement and perceived use by others). Therefore, attitudinal beliefs should be considered differently to reduce the future risk of PES use. For example, teaching gym users how to resist the influence to engage in PES use under risk-promoting circumstances, highlighting the negative consequences of these substances for health (e.g., several adverse effects on cardiovascular system, neuropsychiatric and cognitive pathological alterations, emotional and behavioral dysfunctions) [51], and changing positive attitudes to PES use into negative ones, may decrease intentions to engage in PES use, even among gym users with a history of past/current use [14].

In sum, the global profile shows that PES users are those who (a) want to achieve a specific objective, unattainable through regular methods, (b) considerably increase muscle mass, or over shape the body, (c) improve their physical condition to a much higher level than what is possible with regular methods or (d) recover faster from an injury, (e) resist engaging in excessively frequent training schedules, (f) are advised by friends, or seek encouragement on the Internet and (g) those with less education and (h) positive beliefs and intentions for PES use. Understanding the profile of gym users who use PES may help to identify those who are most vulnerable to PES use. This information may be used to develop educational campaigns, harm reduction initiatives, or set up rules and regulations aiming to cease use and persuade potential users from adopting such behavior [22,52]. On the other hand, when designing prevention strategies, it is important to consider personality traits and characteristics that can influence substance use, such as low self-esteem [53], having a greater tendency to have behavioral or emotional problems, superman complex [54], and perfectionism [55]. Considering this information, educational strategies ought to be adapted to the target groups, improving public policies with the aim of preventing abusive use of PES in these settings. The development of these strategies should consider the following guidelines [56]: (a) guarantee the quality and accuracy of the content of the messages that are intended to be “passed on”, as well as the way in which these are transmitted, reinforcing the negative health consequences of these substances which often appear years after the beginning of PES use; (b) use of emerging information and communication technologies as means for disseminating educational and informational content (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) which have great viral potential and appeal to the emotional side of readers; (c) involvement of instructors/personal trainers who work in gyms and fitness centers who must be trained to educate gym-goers about the negative impact of taking illicit substances and about healthy alternatives [57]; (d) involvement of the exercise participant himself in the development of strategic prevention programs, in order to develop personalized tools and resources, promoting the active engagement of target groups, thus increasing the likelihood of success of the intervention.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that any educational intervention must be subject to recurrent evaluation to ascertain its effectiveness or allow its restructuring to reduce behavior or intention to use illicit substances that improve performance.

While providing insightful findings about gym goers’ characteristics and psychosocial determinants toward PES use in a gym/fitness context, this study has some limitations. First, the results of this study cannot be generalized to the population of Portuguese gym-goers as a random-stratified sampling technique was not used. However, a census of gym users is inexistent, hence a convenience sampling procedure is a reasonable strategy to target specific groups and has been used frequently in similar studies [16]. Secondly, causal inferences cannot be made because of the cross-sectional design of this study. Studies that feature longitudinal designs would be extremely valuable to examine any causal relationships between socio-demographic variables and identify significant predictors and PES use [10]. Thirdly, PES use was measured by self-report and therefore it is subject to response bias and social desirability [58]. However, this issue might have been minimized by guaranteeing participants’ anonymity and confidentiality; specifically, participants received the questionnaires by mail and through a social network (Facebook) and completed the questionnaires in complete privacy with no personal identification being collected. Fourth, we assessed self-reported PES use only in terms of current use. Future research should also explore how dissatisfaction with one’s own body image and related anxiety about one’s appearance (e.g., social physique anxiety) might motivate PES use aimed at improving psychological well-being [41].

5. Conclusions

The present study provides information which can contribute to building interventions targeting persistent PES users in a gym/fitness context. A major conclusion is that the global profile of PES users shows that PES users are those who want to achieve specific objectives, increase muscle mass, or shape the body, improve their physical condition, increase performance, recover faster from injury, with higher training frequency, are advised by friends or encouraged by the Internet, and those with less education and positive beliefs and intention for PES use. By identifying and characterizing those who use PES in a gym-fitness context, public health and clinical interventions can target specific groups and be more sustainable, thereby decreasing the need to use these substances, improving health and well-being, and restoring occupational and personal/social life.

Supplementary Materials

The following is available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su14052868/s1: Questionnaire of Attitudes towards Doping in Fitness (QAD-Fit).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.R.T. and S.S.; Methodology, A.S.R.T. and E.C.; Software, E.C.; Validation, A.S.R.T., S.S., and A.R.; Formal Analysis, E.C. and A.R.; Investigation, A.S.R.T. and S.S.; Resources, A.S.R.T. and E.C.; Data Curation, A.S.R.T. and S.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.S.R.T., S.S., and L.C.; Writing—Review & Editing. A.S.R.T., S.S., A.R., E.C., and L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Human Kinetics of Lisbon University (no. 38/2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not publicly available, though the data may be made available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Markland, D.; Ingledew, D.K. Exercice Participation Motives: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective; Hagger, M.S., Chatzisarantis, N.L.D., Eds.; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 302–305. [Google Scholar]

- The European Health and Fitness Association. Fitness against Doping—Interim Report; The European Health and Fitness Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, R.; Simonato, P.; Ruparelia, R.; Roman-Urrestarazu, A.; Martinotti, G.; Corazza, O. The use of supplements and performance and image enhancing drugs in fitness settings: A exploratory cross-sectional investigation in the United Kingdom. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 32, e2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Pediatrics Academy. Use of Performance-Enhancing Substances. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 1103–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hartgens, F.; Kuipers, H. Effects of androgenic-anabolic steroids in athletes. Sport Med. 2004, 34, 513–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, J.R.; Ratamess, N.A. Medical issues associated with anabolic steroid use: Are they exaggerated? J. Sports Sci. Med. 2006, 5, 182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama, G.; Hudson, J.I.; Pope, H.G., Jr. Review: Long-term psychiatric and medical consequences of anabolic–androgenic steroid abuse: A looming public health concern? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pope, H.G.; Kanayama, G.; Hudson, J.I. Risk factors for illicit anabolic-androgenic steroid use in male weightlifters: A cross-sectional cohort study. Biol Psychiatry. 2012, 71, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pope, H.G.; Wood, R.I.; Rogol, A.; Nyberg, F.; Bowers, L.; Bhasin, S. Adverse health consequences of performance-enhancing drugs: An endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr. Rev. 2014, 35, 341–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhouse, S.; Whitaker, L.; Mckenna, J. Social Psychology of Doping in Sport: A Mixed-Studies Narrative Synthesis; World Anti-Doping Agency: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2015; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, A.S.R.; Serpa, S.; Horta, L.; Carolino, E.; Rosado, A. Prevalence of Performance-Enhancing Substance Use and Associated Factors among Portuguese Gym/Fitness Users. Subst. Use Misuse 2020, 55, 1059–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Residual Effects of Past on Later Behavior (PSPR2002).pdf. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 6, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lazuras, L.; Barkoukis, V.; Rodafinos, A.; Tzorbatzoudis, H. Predictors of Doping Intentions in Elite-Level Athletes: A Social Cognition Approach. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2010, 32, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wiefferink, C.H.; Detmar, S.B.; Coumans, B.; Vogels, T.; Paulussen, T.G.W. Social psychological determinants of the use of performance-enhancing drugs by gym users. Health Educ. Res. 2008, 23, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dunn, M.; Mazanov, J.; Sitharthan, G. Predicting future anabolic-androgenic steroid use intentions with current substance use: Findings from an internet-based survey. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2009, 19, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet, C.; Valois, P.; Buist, A.; Côté, M. Predictors of the use of performance-enhancing substances by young athletes. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2010, 20, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucidi, F.; Zelli, A.; Mallia, L.; Grano, C.; Russo, P.M.; Violani, C. The social-cognitive mechanisms regulating adolescents’ use of doping substances. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntoumanis Ng, J.; Barkoukis, V.; Backhouse, S. A Statistical Synthesis of the Literature on Personal and Situational Variables That Predict Doping in Physical Activity Settings; World Anti-Doping Agency: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, A.S.R.; Rosado, A.; Marôco, J.; Calmeiro, L.; Serpa, S. Determinants of the Intention to Use Performance-Enhancing Substances Among Portuguese Gym Users. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitaker, L.; Long, J.; Petróczi, A.; Backhouse, S.H. Athletes’ perceptions of performance enhancing substance user and non-user prototypes. Perform. Enhanc. Health 2012, 1, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, D.S. A-Priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models [Software]. 2017. Available online: http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Barkoukis, V.; Lazuras, L.; Tsorbatzoudis, H.; Rodafinos, A. Motivational and social cognitive predictors of doping intentions in elite sports: An integrated approach. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2013, 23, e330–e340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, A.S.R.; Serpa, S.; Rosado, A. Psychometric properties of the questionnaire of attitudes towards doping in fitness (QAD-Fit). Motriz Rev. Educ. Fis. 2019, 25, e101925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haykin, S. Neural Networks—A Comprehensive Foundation, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: Singapore, 1999; p. 818. [Google Scholar]

- Lingireddy, S.; Brion, G.M. Artificial Neural Networks in Water Supply Engineering; ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2005; p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, V. Sistemas de Apoio à Decisão—Redes Neuronais (MLP). EN/ISEGI. Version 1.1.2007. Available online: https://www.novaims.unl.pt/docentes/vlobo/isegi_SAD/SAD_9_Redes_MLP_6.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Santos, A.M.; Seixas, J.M.; Pereira, B.B.; Medronho, R.A. Usando Redes Neurais Artificiais e Regressão Logística Predição da Hepatite, A. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2005, 8, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abdi, H.; Valentin, D. Multiple Correspondence Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Alboukadel, K. Practical Guide to Principal Component Methods in R. STHDA.com. 2017, p. 152. Available online: http://www.sthda.com/english/upload/principal_component_methods_in_r_preview.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Gilula, Z.; Haberman, S.J.; van der Heijden, P.G.M. Multivariate Analysis: Discrete Variables (Correspondence Models). In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Neil, J., Smelser, P., Balte, B., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 10218–10221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negre, E.; Arru, M.; Rosenthal-Sabroux, C. Toward a Modeling of Population Behaviors in Crisis Situations. In How Information Systems Can Help in Alarm/Alert Detection; Florence, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, I.K. Doping and the perfect body expert: Social and cultural indicators of performance-enhancing drug use in Danish gyms. Sport Soc. 2010, 13, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, D.C.; Sousa, R.M.L.; Júnior, A.L.R.C.; Veloso, H.J.F. Factors associated with anabolic steroid use by exercise enthusiasts. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2020, 26, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Falasi, O.; Al-Dahmani, K.; Al-Eisaei, K.; Al-Ameri, S.; Al-Maskari, F.; Nagelkerke, N.; Schneider, J. Knowledge, attitude and practice of anabolic steroids use among gym users in Al-Ain district, United Arab Emirates. Open Sport Med. J. 2009, 2, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Unemployment Statistics and Beyond. Eurostat Statistics Explained. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Unemployment_statistics_and_beyond#How_does_educational_level_affect_unemployment_.3F (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Henkel, D. Unemployment and substance use: A review of the Literature (1990–2010). Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2011, 4, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayllón, S.; Ferreira-Batista, N.N. Unemployment, drugs and attitudes among European youth. J. Health Econ. 2018, 57, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertava Health Massachusetts Rehab. Unemployment & Substance Abuse; Vertava Health: Cummington, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dores, A.R.; Carvalho, I.P.; Burkauskas, J.; Simonato, P.; De Luca, I.; Mooney, R.; Ioannidis, K.; Gómez-Martínez, M.A.; Demetrovics, Z.; Abel, K.E.; et al. Exercise and Use of Enhancement Drugs at the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multicultural Study on Coping Strategies During Self-Isolation and Related Risks. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 648501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockerill, I.M.; Riddington, M.E. Exercise dependence and associated disorders: A review. Couns. Psychol. Q. 1996, 9, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, O.; Simonato, P.; Demetrovics, Z.; Mooney, R.; van de Ven, K.; Roman-Urrestarazu, A.; Rácmolnár, L.; de Luca, I.; Cinosi, E.; Santacroce, R.; et al. The emergence of Exercise Addiction, Body Dysmorphic Disorder, and other image-related psychopathological correlates in fitness settings: A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lima, L. A prevenção do tabagismo na adolescência. In Promoção da Saúde: Modelos e Práticas de Intervenção no Âmbito da Atividade Física, Nutrição e Tabagismo; Sardinha, L., Matos, M., Loureiro, I., Eds.; Edições FMH: Lisboa, Portugal, 1999; pp. 123–161. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, E.; Dittmar, H.; Orsborn, A. The effects of exposure to muscular male models among men: Exploring the moderating role of gym use and exercise motivation. Body Image 2007, 4, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agliata, D.; Tantleff-Dunn, S. The Impact of Media Exposure on Males’ Body Image. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 23, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilkens, L.; Cruyff, M.; Woertman, L.; Benjamins, J.; Evers, C. Social Media, Body Image and Resistance Training: Creating the Perfect ‘Me’ with Dietary Supplements, Anabolic Steroids and SARM’s. Sports Med. Open 2021, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piacentino, D.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Longo, L.; Pavan, A.; Stivali, L.; Stivali, G.; Ferracuti, S.; Brugnoli, R.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V.; et al. Body Image and Eating Disorders are Common among Professional and Amateur Athletes Using Performance and Image Enhancing Drugs: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2017, 49, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bahrke, M.S. Performance-enhancing substance misuse in sport: Risk factors and considerations for success and failure in intervention programs. Subst. Use Misuse 2012, 20, 1505–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozzi, G.; Salerno, M.; Pomara, C.; Sessa, F. Neuropsychiatric and Behavioral Involvement in AAS Abusers. A Literature Review. Medicina 2019, 55, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christiansen, A.V.; Vinther, A.S.; Liokaftos, D. Outline of a typology of men’s use of anabolic androgenic steroids in fitness and strength training environments *. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2017, 24, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, H.R. The Role of Self-esteem in Tendency towards Drugs, Theft and Prostitution. Addict. Health 2011, 3, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, S. The Sport Psych Handbook; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan, D.J.; Stoeber, J.; Passfield, L. Perfectionism, and attitudes towards doping in junior athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 34, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkoukis, V.; Lazuras, L.; Tsorbatzoudis, H. The Psychology of Doping in Sport; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; 248p. [Google Scholar]

- Horta, L. Doping e treino da força: Dois caminhos, uma opção. In Treino da Força—Volume 2, Avaliação, Planeamento e Aplicações; Correia, P., Mil Homens, P., Mendonça, G., Eds.; Edições FMH: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017; pp. 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Gucciardi, D.F.; Jalleh, G.; Donovan, R.J. Does social desirability influence the relationship between doping attitudes and doping susceptibility in athletes? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010, 11, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).