Relationship between Related Party Transactions and the Social Contribution Activities of South Korean Chaebol Companies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

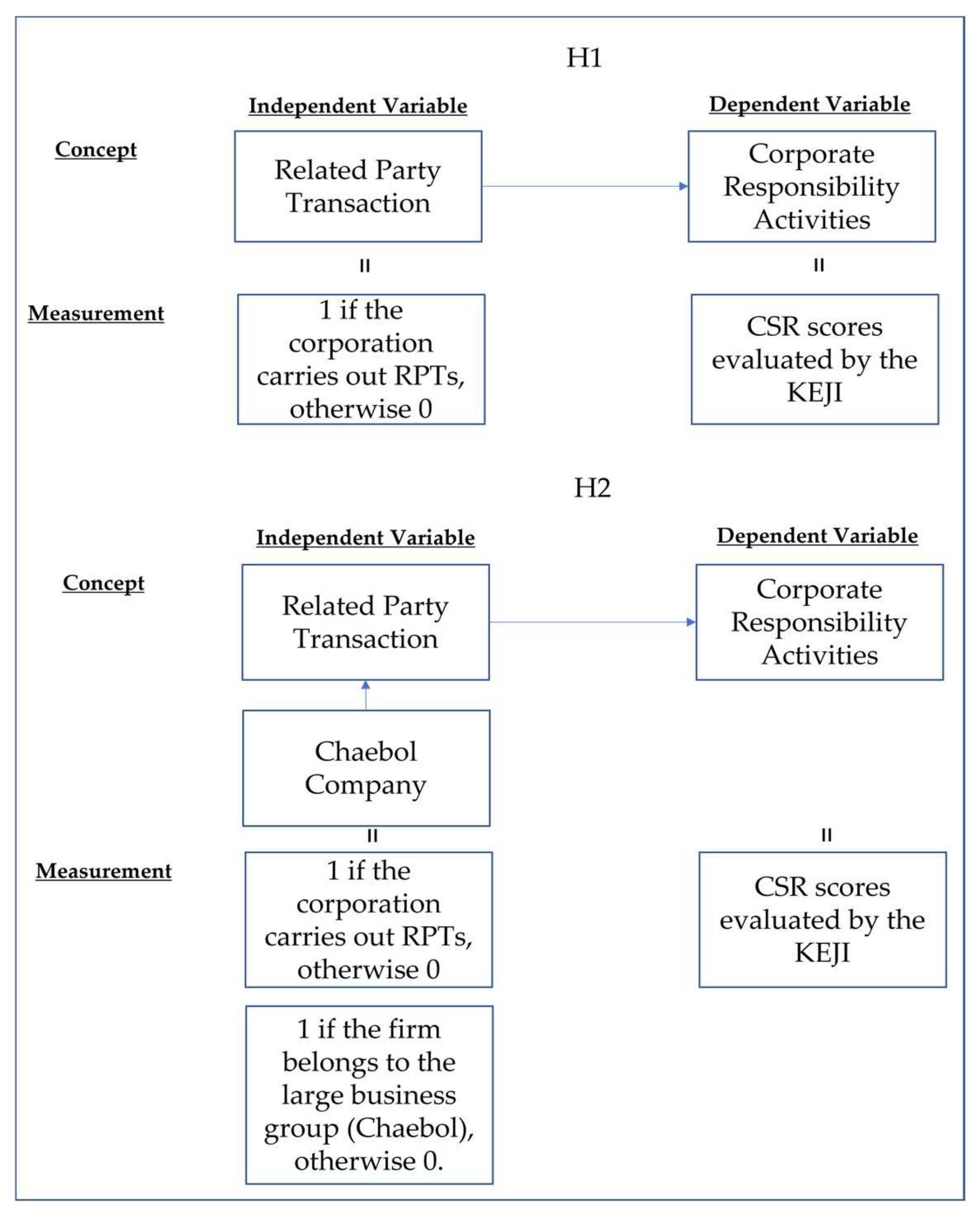

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. CSR Activities

2.2. RPT

2.3. Hypothesis Formulation

3. Methodology

3.1. RPTs

3.2. CSR

3.3. Research Design and Sample Selection

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

4.2. Main Results

Impact of RPT on CSR

4.3. Further Analysis

5. Implication, Conclusions, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beaudoin, C.A. Earnings Management: The Role of the Agency Problem and Corporate Social Responsibility; Drexel University: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chih, H.L.; Shen, C.H.; Kang, F.C. Corporate social responsibility, investor protection, and earnings management: Some international evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 79, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, C.A.; Maclagan, P.W. Managers’personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. JBE 2004, 50, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Barnea, A.; Rubin, A. Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, M.; Wong, T.J. Propping through related party transactions. Rev. Account. Stud. 2010, 15, 70–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.J.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, M.G.; Park, J.C. The association between related-party transactions and control-ownership wedge: Evidence from Korea. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2014, 29, 227–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.S.; Wong, K.S. A study of the relationship between corporate governance structures and the extent of voluntary disclosure. JIAAT 2001, 10, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanou, I.; Vafeas, N. The association between corporate boards, audit committees, and management earnings forecasts: An empirical analysis. J. Account. Res. 2005, 43, 453–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Instrumental stakeholder theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. AMR 1995, 20, 404–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance–financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, M.S.; Wier, B. Is earnings quality associated with corporate social responsibility? Account. Rev., 2012, 87, 761–796. Account. Rev. 2012, 87, 761–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. JFE 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, D.; Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A. Are socially responsible managers really ethical? Exploring the relationship between earnings management and corporate social responsibility. Corp. Govern. Int. Rev. 2008, 16, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muttakin, M.B.; Khan, A.; Azim, M.I. Corporate social responsibility disclosures and earnings quality. Manag. Aud. J. 2015, 30, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salewski, M.; Zulch, H. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Financial Reporting Quality-Evidence from European Blue Chips; HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management: Saxony, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Verschoor, C.C. Is there financial value in corporate values? Strateg. Financ. 2005, 87, 17–18, Gale Academic OneFile. Available online: link.gale.com/apps/doc/A133858703/AONE?u=anon~3e1d4d99&sid=googleScholar&xid=0ea1a0b7 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Linthicum, C.; Reitenga, A.; Sanchez, J. Social responsibility and corporate reputation: The case of the Arthur Andersen Enron audit failure. J. Account. Public Policy 2010, 29, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A. Corporate ownership around the world. J. Finance 1999, 54, 471–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, S.; Djankov, S.; Lang, L. The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. JFE 2000, 58, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classens, S.; Djankov, S.; Fan, J.; Lang, L. Disentangling the incentives and entrenchment effects of large shareholdings. J. Financ. 2002, 57, 2741–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wong, T.J. Corporate ownership structure and the informativeness of accounting earnings in East Asia. JAE 2002, 33, 401–425. [Google Scholar]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R. Investor protection and corporate valuation. J. Financ. 2002, 57, 1147–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwon, J.H. Formation of corporate governance in Korea: The rise of chaebols (1910–1980). EAJBM 2015, 5, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. A survey of corporate governance. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 737–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.; Qi, Y.; Rau, P.R.; Stouraitis, A. Buy high, sell low: How listed firms price asset transfers in related party transactions. JBF 2009, 33, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Boone, P.; Breach, A.; Friedman, E. Corporate governance in the Asian financial crisis. JFE 2000, 58, 141–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harjoto, M.A.; Jo, H. Corporate governance and CSR nexus. JBE 2011, 100, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrecchia, R. Discretionary disclosure. JAE 1983, 5, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, L.H.; Amato, C.H. The effects of firm size and industry on corporate giving. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 3, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Pae, J.; Yoo, C. Business groups and tunneling: Evidence from corporate charitable contributions by Korean companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 154, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, C.; Pae, J. Corporate charitable contributions: Business award winners’ giving behaviors. Bus. Ethics Euro. Rev. 2016, 25, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. AMR 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blindheim, B.T.; Langhelle, O. A reinterpretation of the principles of CSR: A pragmatic approach. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | 25% | Median | 75% | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 62.343 | 2.959 | 52.863 | 60.328 | 62.484 | 64.269 | 72.264 |

| RPT | 0.845 | 0.362 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| CHA | 0.184 | 0.388 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| SIZE | 26.819 | 1.113 | 24.461 | 26.078 | 26.682 | 27.437 | 30.864 |

| LEV | 0.764 | 0.758 | 0.001 | 0.249 | 0.580 | 0.983 | 6.867 |

| MB | 1.302 | 1.108 | 0.279 | 0.648 | 0.965 | 1.510 | 7.131 |

| ROE | 0.055 | 0.092 | −1.068 | 0.021 | 0.048 | 0.087 | 0.632 |

| LAR | 0.455 | 0.168 | 0.075 | 0.346 | 0.461 | 0.549 | 2.493 |

| FOR | 0.110 | 0.129 | 0.000 | 0.025 | 0.064 | 0.149 | 0.771 |

| CSR | RPT | CHA | SIZE | LEV | MB | ROE | LAR | FOR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 1.000 | 0.043 | −0.045 | 0.065 | −0.063 | 0.143 | 0.062 | −0.173 | 0.107 |

| (0.2647) | (0.2358) | (0.089) | (0.1011) | (0.0002) | (0.1045) | (<0.0001) | (0.0051) | ||

| RPT | 1.000 | 0.028 | 0.112 | 0.021 | −0.098 | −0.050 | 0.075 | 0.024 | |

| (0.4609) | (0.0034) | (0.5772) | (0.01) | (0.1868) | (0.0484) | (0.5213) | |||

| CHA | 1.000 | 0.452 | 0.074 | −0.107 | 0.024 | −0.006 | 0.137 | ||

| (<0.0001) | (0.0516) | (0.0048) | (0.534) | (0.8681) | (0.0003) | ||||

| SIZE | 1.000 | 0.158 | −0.077 | 0.099 | 0.067 | 0.426 | |||

| (<0.0001) | (0.044) | (0.0091) | (0.0804) | (<0.0001) | |||||

| LEV | 1.000 | 0.074 | −0.185 | −0.050 | −0.117 | ||||

| (0.0509) | (<0.0001) | (0.1928) | (0.0021) | ||||||

| MB | 1.000 | 0.118 | −0.143 | 0.032 | |||||

| (0.002) | (0.0002) | (0.3959) | |||||||

| ROE | 1.000 | −0.018 | 0.123 | ||||||

| (0.6397) | (0.0012) | ||||||||

| LAR | 1.000 | −0.075 | |||||||

| (0.0498) | |||||||||

| FOR | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Variables | (1) Y = CSR | (2) Y = CSR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | |

| Intercept | 52.747 | (16.15) *** | 52.365 | (16.09) *** |

| RPT | 0.610 | (2.00) ** | 0.947 | (2.86) *** |

| CHA | −0.605 | (−1.9) * | 1.168 | (1.53) |

| RPT × CHA | −2.055 | (−2.55) ** | ||

| SIZE | 0.359 | (2.86) *** | 0.362 | (2.89) *** |

| LEV | −0.493 | (−3.05) *** | −0.465 | (−2.88) *** |

| MB | 0.315 | (3.09) *** | 0.314 | (3.1) *** |

| ROE | 0.314 | (0.25) | 0.353 | (0.29) |

| LAR | −2.160 | (−3.2) *** | −2.232 | (−3.31) *** |

| FOR | 0.102 | (0.11) | 0.137 | (0.14) |

| Σ IND, ΣYR | Included | Included | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.1116 | 0.1189 | ||

| F Statistics | 5.32 *** | 5.42 *** | ||

| Sample Size | 689 | 689 | ||

| Variables | (1) Chaebol Sample | (2) Non-Chaebol Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | |

| Intercept | 68.604 | (8.75) *** | 48.236 | (12.29) *** |

| RPT | −0.813 | (−1) | 0.915 | (2.75) *** |

| SIZE | −0.282 | (−0.94) | 0.526 | (3.51) *** |

| LEV | −0.109 | (−0.26) | −0.547 | (−3.1) *** |

| MB | 1.152 | (2.36) ** | 0.264 | (2.55) ** |

| ROE | −1.056 | (−0.25) | −0.171 | (−0.13) |

| LAR | −1.829 | (−0.92) | −1.885 | (−2.59) *** |

| FOR | 2.510 | (0.96) | −0.673 | (−0.64) |

| Σ IND, ΣYR | Included | Included | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.1288 | 0.1246 | ||

| F Statistics | 2.03 ** | 5.20 *** | ||

| Sample Size | 127 | 562 | ||

| Variables | (1) Y = CSR1 | (2) Y = CSR2 | (3) Y = CSR3 | (4) Y = CSR4 | (5) Y = CSR5 | (6) Y = CSR6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | t−Value | Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | |

| Intercept | 7.583 | (3.27) *** | 16.979 | (10.64) *** | 1.193 | (0.66) | 10.250 | (17.26) *** | 3.515 | (6.71) *** | 12.559 | (8.52) *** |

| RPT | −0.063 | (−0.29) | 0.019 | (0.13) | 0.535 | (3.19) *** | −0.019 | (−0.35) | −0.001 | (−0.04) | 0.112 | (0.82) |

| CHA | 0.301 | (1.33) | −1.116 | (−7.16) *** | 0.000 | (0) ** | 0.008 | (0.15) | 0.197 | (3.88) *** | −0.015 | (−0.11) |

| SIZE | 0.352 | (3.94) *** | −0.038 | (−0.62) | 0.170 | (2.46) *** | −0.008 | (−0.39) | 0.050 | (2.5) ** | −0.137 | (−2.41) ** |

| LEV | −0.285 | (−2.48) ** | −0.124 | (−1.58) | −0.134 | (−1.51) ** | 0.000 | (0.01) | 0.017 | (0.69) | −0.006 | (−0.09) |

| MB | 0.172 | (2.38) ** | 0.069 | (1.4) | 0.138 | (2.48) | −0.038 | (−2.08) ** | −0.028 | (−1.78) * | −0.001 | (−0.04) |

| ROE | −1.158 | (−1.32) | 0.032 | (0.05) | 0.353 | (0.52) ** | 0.166 | (0.74) | 0.578 | (2.86) *** | 0.063 | (0.11) |

| LAR | −2.213 | (−4.61) *** | −0.052 | (−0.16) | 0.347 | (0.94) | −0.241 | (−1.97) ** | −0.153 | (−1.42) | 0.101 | (0.33) |

| FOR | 0.605 | (0.88) | 0.197 | (0.42) | 0.310 | (0.58) | −0.262 | (−1.5) | 0.163 | (1.05) | −0.767 | (−1.76) * |

| Σ IND, ΣYR | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | ||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.0924 | 0.0881 | 0.0461 | 0.0792 | 0.1362 | 0.0254 | ||||||

| F Statistics | 4.50 *** | 4.33 *** | 2.66 *** | 3.96 *** | 6.34 *** | 1.90 ** | ||||||

| Sample Size | 689 | 689 | 689 | 689 | 689 | 689 | ||||||

| Variables | (1) Y = CSR1 | (2) Y = CSR2 | (3) Y = CSR3 | (4) Y = CSR4 | (5) Y = CSR5 | (6) Y = CSR6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | Coef. | t-Value | |

| Intercept | 7.600 | (3.27) *** | 16.919 | (10.59) *** | 0.974 | (0.54) | 10.214 | (17.19) *** | 3.495 | (6.67) *** | 12.521 | (8.48) *** |

| RPT | −0.078 | (−0.33) | 0.072 | (0.44) | 0.729 | (4.01) *** | 0.011 | (0.19) | 0.018 | (0.34) | 0.146 | (0.97) |

| RPT × CHA | 0.092 | (0.16) | −0.322 | (−0.81) | −1.183 | (−2.67) *** | −0.190 | (−1.3) | −0.120 | (−0.94) | −0.203 | (−0.56) |

| CHA | 0.221 | (0.4) | −0.838 | (−2.23) ** | 1.021 | (2.43) ** | 0.173 | (1.24) | 0.301 | (2.47) ** | 0.160 | (0.46) |

| SIZE | 0.352 | (3.93) *** | −0.037 | (−0.61) | 0.172 | (2.5) ** | −0.008 | (−0.38) | 0.050 | (2.5) ** | −0.136 | (−2.41) ** |

| LEV | −0.286 | (−2.49) ** | −0.120 | (−1.51) | −0.117 | (−1.33) | 0.003 | (0.1) | 0.019 | (0.75) | −0.004 | (−0.05) |

| MB | 0.172 | (2.38) ** | 0.069 | (1.4) | 0.138 | (2.48) ** | −0.038 | (−2.09) ** | −0.029 | (−1.78) * | −0.002 | (−0.04) |

| ROE | −1.160 | (−1.32) | 0.038 | (0.06) | 0.375 | (0.55) | 0.169 | (0.75) | 0.580 | (2.87) *** | 0.067 | (0.12) |

| LAR | −2.210 | (−4.59) *** | −0.063 | (−0.19) | 0.306 | (0.83) | −0.248 | (−2.02) ** | −0.157 | (−1.46) | 0.094 | (0.31) |

| FOR | 0.603 | (0.88) | 0.202 | (0.43) | 0.330 | (0.63) | −0.259 | (−1.48) | 0.166 | (1.07) | −0.763 | (−1.75) * |

| Σ IND, ΣYR | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | ||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.0911 | 0.0877 | 0.0836 | 0.0801 | 0.1361 | 0.0244 | ||||||

| F-Statistics | 4.28 *** | 4.15 *** | 2.90 *** | 3.85 *** | 6.08 *** | 1.82 ** | ||||||

| Sample Size | 689 | 689 | 689 | 689 | 689 | 689 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ryu, H.; Chae, S.-J. Relationship between Related Party Transactions and the Social Contribution Activities of South Korean Chaebol Companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052834

Ryu H, Chae S-J. Relationship between Related Party Transactions and the Social Contribution Activities of South Korean Chaebol Companies. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052834

Chicago/Turabian StyleRyu, Haeyoung, and Soo-Joon Chae. 2022. "Relationship between Related Party Transactions and the Social Contribution Activities of South Korean Chaebol Companies" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052834

APA StyleRyu, H., & Chae, S.-J. (2022). Relationship between Related Party Transactions and the Social Contribution Activities of South Korean Chaebol Companies. Sustainability, 14(5), 2834. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052834