Abstract

Unlike Western corporations, Chinese companies have yet to widely adopt corporate social advocacy (CSA) as a proactive strategy for corporate communication due to the different cultures and business environments. With only a handful of Chinese companies committing to CSA communication, the consequences of such practice on consumer relationship building and maintenance remain elusive. In light of expectancy violations theory (EVT), this study explores Chinese consumers’ expectations of domestic CSA on the issue of same-sex marriage and the effects of proactive corporate social advocacy communication. Through structure equation modeling of 418 survey responses, this study examines the relationship between the violation of Chinese consumers’ expectations of CSA and the quality of consumer relationships through the mediation of violation valence, violation expectedness, and relationship certainty.

1. Introduction

Increasingly, US companies are overtly expressing their stances on controversial social and political issues such as gun control, reproductive rights, and same-sex marriage. The adoption of corporate social advocacy (CSA) by major corporations, such as Starbucks, PayPal, and Amazon in the United States indicates that CSA has emerged as an important proactive public relations and corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategy [1,2,3]. Although many visionary Chinese companies have been looking to their Western counterparts as benchmarks for strategic public relations and CSR practices [4,5,6], very few Chinese companies choose to engage in CSA on controversial social and political issues, to remain on the “safe” side in the traditional Chinese political and social climate [7,8,9].

On 24 May 2017, Taiwan became the first place in Asia to legalize same-sex marriage, marking a civil rights development in Eastern societies [10]. This move was hailed by members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community in China—which has the world’s largest LGBT population and shares a common language and culture with Taiwan [11]—as a model for other Chinese societies to follow [12]. Although observers have noted that LGBT rights and marriage equality are no longer fringe issues in Chinese public discourse [13,14], advocacy for same-sex marriage in China is still largely limited to gay communities and activists [15]. Unlike in Taiwan or in the US, the gay rights movement in China remains a grassroots affair [12]. Only a few companies have joined the advocacy effort by subtly featuring gay couples in their advertisements or changing logos to include rainbow colors [16,17]. These ongoing social changes challenge traditional Chinese norms and put pressure on the broader for-profit sector in China, as public relations practitioners in the country are confronted with the question of how CSA communication would (or if it would) affect companies’ relationships with native consumers. However, academic research on CSA among Chinese companies remains sparse. To fill this research gap, this study aims to empirically explore how Chinese consumers respond to domestic companies’ CSA on the issue of same-sex marriage.

Additionally, while some CSA studies have focused heavily on the effects of CSA on financial outcomes such as purchase intentions [3] and boycotts [18,19], others have considered CSA as a strategic tool for building quality relationships by measuring the outcomes of brand loyalty and brand trust [20,21]. Extending this line of research, this study attempts to illuminate the role of CSA in organizational relationship building in the Chinese market by highlighting organization–public relationships (OPRs) as a potential outcome of CSA communications.

Lastly, this study adopts the lens of expectancy violations theory (EVT) [22,23], which was developed in interpersonal communication studies to predict information processing and relationship changes under the circumstances of expectancy violations. EVT assumes that individuals make predictions about actions others are likely to take in given situations; these predicted behaviors constitute expectations [24]. Expectancy violations occur when these predictions are defied. In the context of CSA for marriage equality in China, the extent to which a company’s public support for legalization of same-sex marriage might constitute a violation of expectations for Chinese individuals is determined by whether the individual expects the company to take that action, and once taken, whether that stance accords with the position the individual expected the company to take [25]. Given the rudimentary status of CSA in China [26], the sensitivity of the issue, and the Chinese sociopolitical environment [11,15], the authors conjecture that many Chinese consumers would have relatively low expectations of domestic companies engaging in CSA for same-sex marriage. Thus, when learning about such actions being taken by a few Chinese companies (e.g., TMall, Xiami Music, and Youku), consumers may feel surprised, and a violation of expectations may occur. The current study adopts EVT to understand how the violation of Chinese consumers’ prescriptive and predictive expectancies regarding CSA affect the different dimensions of OPRs, through the mediation of violation valence, violation expectedness, and relationship certainty, and the moderation of perceived CSA authenticity.

With its strategic focus on the Chinese market, the study contributes to public relations theory building by applying EVT to reveal the mechanisms by which a foreign public relations communication strategy like CSA affects organization–public relationships. In addition, prior investigation of CSA has largely taken place in Western liberal democratic societies. This study extends this research to the Chinese context to understand how publics there perceive this emerging form of corporate sociopolitical involvement in progressive issues such as marriage equality. This study thus provides practical implications for Chinese companies, as well as for multinational corporations with intentions to build, maintain, and improve relationships with Chinese consumers.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Social Advocacy

The topic of corporate social advocacy has received increasing interest from social sciences researchers in recent years, as many large consumer companies in the United States are openly taking a stand on controversial social or political issues such as same-sex marriage, gun control, immigration, and legalization of marijuana [1,2,3,18,19,20,21,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. While CSA is conceptualized in slightly different ways, a widely cited definition of the term is the one provided by Dodd and Supa [2,34], who wrote CSA is a public relations function where firms and/or their CEOs intentionally or unintentionally “align themselves with a controversial social–political issue outside their normal sphere of CSR interest” [2]. Dodd and Supa [34] distinguished the term from related public relations concepts such as strategic issues management and CSR, arguing that the social–political issue involved in a CSA activity is not necessarily tied to the company and that engaging in such an activity may alienate certain stakeholders. In other words, CSA issues usually involve some level of controversy; publicly taking a stance on such an issue may fulfill the expectations of some stakeholders while violating the expectations of others [2].

Instead of using the term CSA, Wettstein and Baur [1] referred to this type of corporate engagement as “corporate political advocacy” (CPA) and defined it as corporations “voicing or showing explicit and public support for certain individuals, groups, or ideals and values with the aim of convincing and persuading others to do the same.” Companies engaging in CPA are promoting the issues or related values and ideals for their own sake, regardless of their connection to the core business of the company. It differs from CSR in that it pursues not the balancing of stakeholder interests, but rather normative convictions shared by some stakeholders but not others.

Ciszek and Logan [27] further reasoned that companies engaging in CPA are actually challenging the consensus-oriented tradition of public relations scholarship. Rather than centering on consensus as the preferred public relations outcome, CPA brings about dissensus—in line with the postmodern values of advocating multiple voices.

Nalick et al. [26] approached the concept in a broader sense, under the umbrella term of corporate “sociopolitical involvement” (SPI). These authors, too, pointed out that the issues SPI engages with are characterized by a lack of societal consensus. Additionally, the issues always have a high degree of salience, meaning that they are important to a large segment of society and are current. Based on these criteria, same-sex marriage can be considered a sociopolitical issue in China, particularly in the wake of Taiwan’s legalization of gay marriage, because the event primed the issue in China, and provoked wide discussion online [12,14].

Yim [32] contended that the conceptualization of CSA should take into account public expectations. Although CSA may be controversial, the legitimacy of CSA can be “created, maintained, and defended” by the company itself, if the CSA engagement is consistent with public expectations of the company and corporate standards of behavior. Both studies understand CSA as responses to social norms and stakeholder expectations, rather than one-way communication from the companies.

Some studies have been done to examine the effectiveness of CSA. Dodd and Supa [2] investigated the relationship between CSA on the issue of legalizing same-sex marriage (whether supporting or opposing it) and consumers’ purchase intentions. Overton, et al. [3] examined the influence of Nike’s CSA efforts around the issue of racial equality on consumers in light of the theory of planned behavior. The results suggested that individual consumer attitudes toward Nike’s CSA efforts as well as their subjective norms were positively related to purchase intentions and word-of-mouth intentions. Browning et al. [25] also investigated the effects of CSA on public perceptions. The findings largely supported the hypothesis that improved feelings of communicated commitment stemming from CSA engagement would positively influence OPR outcomes, in turn increasing stakeholders’ willingness to support the organization. Park and Jiang’s [20] study revealed that, through CSA, a company could signal to stakeholders a commitment to some controversial position and attract the attention of those who share that identity. These people would support the company emotionally and behaviorally.

In the same vein, the current study aims to empirically explore CSA from the perspective of public relations, specifically by looking at its relationship with the organization–public relationship (OPR), a key concept in public relations that involves relationship outcomes, such as trust, commitment, satisfaction, and control mutuality [35,36,37]. Before discussing this relationship in more detail, however, a short introduction is necessary on the status of CSA in China.

2.2. Same-Sex Marriage and CSA in China

An increased number of Chinese companies have integrated aspects of CSR into their operations in accordance with a higher public demand for general CSR information [4,5,6,38], but very few have expressed public support for or opposition to sociopolitical issues. According to Nalick et al. [26], a “sociopolitical issue” is characterized by a lack of societal consensus, evolving views, and a high degree of issue salience in a particular society. In view of these criteria, same-sex marriage is a sociopolitical issue in China, not only because there is a large LGBT population, but also because the issue has received much attention from different groups in the society in recent years [14,39,40,41].

On the Chinese social media platform Weibo, the hashtag “#same-sex marriage” had registered more than 26 million views and 251 thousand discussions as of 7 February 2022 (not counting posts that had been deleted). The hashtag “#lawmaker urged to include same-sex marriage in Civil Code” occurred in 292 thousand posts, which were viewed 840 million times. There was even a “super topic” for same-sex marriage, which serves as an easy-to-find information hub for interested followers.

Despite the widespread interest on social media, advocacy for same-sex marriage in China is still fledgling [15]. Gay marriage is controversial for many, as it is a challenge to traditional Chinese family values. The Chinese government today largely takes an apparently hands-off approach, characterized by “no approval, no disapproval, and no promotion” [17]. State control of the media and civic sector has limited venues for organized advocacy on LGBT issues [15].

Chinese companies are used to taking cues from government and the political environment [7]. This is evident in how they engage in CSR. Studies by Yin and Zhang [6] and Banik and Lin [42] revealed that Chinese companies adopted CSR for a number of pragmatic reasons, such as securing political and administrative backing. Additionally, due to their positions in global supply chains, Chinese companies use CSR to cultivate reputations among international stakeholders.

Chinese companies have nonetheless shown interest in the purchasing power of the LGBT consumer market, which is estimated to be as high as USD 300 billion [43]. Technology firms are leading the way here, since their customer bases are dominated by increasingly liberal and progressive young people [44]. A survey of more than 18,000 LGBT people in China found that 56% of men and 62% of women viewed LGBT-friendly policies and regulations as the most important factor influencing their purchasing decisions [45]. Given these developments, the social environment seems more and more encouraging for Chinese companies to engage in CSA on the issue of same-sex marriage.

2.3. Expectancy Violations Theory (EVT)

Although EVT was originally developed as an interpersonal communication model to explain how individuals respond to unanticipated violations of expectations of personal distance [46,47], the theory was later applied to a variety of communication contexts with a focus on the impact of expectancy violations on interaction outcomes [22,48,49,50]. According to EVT, a violation of expectancy happens when there is a perceived discrepancy between an expected behavior and what actually occurs, with an expectancy understood as an “enduring pattern of anticipated behavior” (46. Taking a more general view, Burgoon [51] regarded expectations as a combination of both social norms and known idiosyncrasies of the interactants. The basic thesis of EVT is that there are circumstances under which violations of social norms and expectations may be strategically superior to conformity [47].

While the notion of expectations has been frequently used by public relations scholars to help define the relationship that exists between an organization and key publics—often in the sense that expectations are a relationship imperative [52,53,54,55]—there are few applications of the expectancy violations model to public relations. For example, Park et al. [21] applied EVT to a corporate social responsibility communication context to examine consumer responses to CSR messages. In a similar vein, Kim [50] extended EVT to the investigation of OPRs in a crisis setting, in which the crisis was considered as a violation of expectancies. In that study, findings suggested that stakeholder expectancies were significant predictors of the way the violation was perceived, and subsequently, of the relationships between publics and the company. Addressing Olkkonen and Luoma-Aho’s [54] call to deepen the understanding of how expectations affect relationships through the lens of the expectancy violations model, this study utilizes EVT by considering publics’ relationships with an organization—or the OPRs—as the object of expectancies [50,54]. Premised on the possibility of organizations and publics mutually benefiting one another, OPR is defined as “the state that exists between an organization and its key publics in which the action of either entity impacts the economic, social, and political and/or cultural well-being of the other entity” [37] and is characterized by the dimensions of trust, satisfaction, commitment, and control mutuality [56]. The literature has suggested that expectations are one of the key antecedents to OPRs [57]; it thus stands to reason that the violations of expectations also impact OPRs.

Burgoon and Hubbard [48] noted that expectancies entail both what is anticipated to occur (predictive expectancies; i.e., what will happen), and what is desired or preferred (prescriptive expectancies; i.e., what should happen). Following Kim [50], in the present study, the prescriptive expectancy is defined as consumers’ general expectations for Chinese companies to engage in CSA efforts in favor of legalizing same-sex marriage, whereas the predictive expectancy is defined as the expectations for the particular Chinese companies of interest (i.e., Tmall, Xiami Music, and Youku). This operationalization is also consistent with Burgoon and Hubbard’s [48] explanation of prescriptive and predictive aspects of expectancies, as the prescriptive expectancy examines the idealized standards of conduct—the degree to which the particular CSA behavior is regarded as appropriate, desired, or preferred—while the predictive expectancy focuses on actual communicative practice.

EVT posits that expectancies tend to serve as framing devices and perceptual filters, influencing the way that related information is processed and that expectancy-violating behavior is evaluated [58]. As a result, perceptions of the violations may differ in terms of violation expectedness and violation valence [22,47]. According to Burgoon and Hale [46], individuals come not only to anticipate that others will behave in a particular fashion but also to assign evaluations, or “valence”, to these actions. The expectancy violations model posits that positive violations produce more favorable outcomes than conformity to expectations, while negative violations produce less favorable ones. Burgoon and Walther [59] found that the combined effect of the expectedness of behavior and the valence associated with it helps determine outcomes. In the present study, Chinese companies’ incipient CSA activities in favor of legalizing same-sex marriage are considered as an expectancy violation. Such an action is viewed as more positive in valence (meaning it is perceived more positively) and expectedness (meaning it is a less unexpected expectancy violation), if the individual holds higher prescriptive and predictive expectancies (which are consumers’ expectations that Chinese companies in general and the specific Chinese companies of interest, respectively, will engage in CSA efforts in favor of legalizing same-sex marriage). An expectancy violation will be assessed as more negative in valence and less in expectedness if the individual has relatively negative prescriptive and predictive expectancies for the CSA behavior. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

Consumers’ stronger (a) predictive and (b) prescriptive expectancies are related to more positive violation (valence) regarding the company’s CSA message.

H2.

Consumers’ stronger (a) predictive and (b) prescriptive expectancies are related to higher violation expectedness regarding the company’s CSA message.

Expectancy violations are seen as an integral part of relational changes, as the violation is arousing and distracting, directing some attention and cognitive processing towards the unexpected behavior, the characteristics of the violator, the relational implicature, and the meaning of the violation act [47]. Afifi and Burgoon [58] argued that full explanations of the expectancy violations’ impact on relationships should include reference to the degree of relationship certainty change that is produced, rather than ignoring relationship certainty as a variable of study. Relationship certainty/uncertainty refers to the degree of confidence an individual has in the perceptions of his/her involvement within a relationship [60]. Ample evidence suggests that relationship uncertainty can yield negative communication and relational outcomes. Studies have found that relationship uncertainty not only causes difficulties in message production and processing (such as negative evaluations of the relational messages), but also harms perceptions of relationship quality [61,62]. Theiss and Solomon [63] also suggested that a decrease in relationship uncertainty strongly predicted intimacy in a relationship. As Kreye [64] stated, relationship certainty could determine how a relationship develops, as it is the foundation for establishing the key indicators of high-quality organizational relationships, such as trust and commitment. In addition, one of the common assumptions underlying relationship theories is that people want predictability, or certainty, in their relationships [22,65,66]. Ni and Wang [66] found that uncertainty can serve as a mediator of the relationship between relationship cultivation strategies (such as legitimacy, networking, and positivity) and relationship outcomes (i.e., the four OPR dimensions: control mutuality, trust, satisfaction, and commitment), partially explaining the mechanism underlying how people’s perception of corporate behaviors affects the relational outcomes. Based on the existing evidence, this study hypothesizes:

H3.

Relationship certainty is positively related to organization–public relationships.

Relationship uncertainty could stem from doubts about and the perceived ambiguity of relationship partners, whose behaviors could thus either increase or decrease relationship certainty [67]. On one hand, some scholars argued that expectancy violations would lead to increased relationship uncertainty for an individual in a close relationship because unexpected behaviors generally imply more alternative predictions about future behaviors [68,69]. On the other hand, it was suggested that expectancy violations would not necessarily decrease relationship certainty. Previous studies have illustrated several such conditions. For example, unlike expected behaviors that are more socially scripted, unexpected behaviors usually contain more personalized information about the relationship partner, which reveals the uniqueness of the partner. The distinctiveness and informativeness of the unexpected behaviors would increase relationship certainty [70]. Likewise, some unexpected behaviors containing particularly intense emotional displays, such as jealousy, are likely to induce perceptions of relationship significance, thus increasing relationship certainty [22]. The contradictory evidence suggests the nuanced effects of different expectancy violation factors (e.g., violation expectedness and violation valence) on relationship certainty.

While investigating the divergent effects of violations on relationship certainty, Afifi and Burgoon [71] conceptualized congruent violation, which is defined as “behavior that is unexpected, in that it is a significantly more ardent and/or intense behavioral display of an emotion, relational message or persuasive stance, as compared with previous displays of a similar emotion, relational message or persuasive stance” (p. 18). Studies have confirmed that these congruent violations would increase relationship certainty compared to incongruent violations. The key factor that distinguishes the two types of violations is the degree of congruence. It can be inferred that the more congruent the violation behaviors are, the stronger will be the violation expectedness. In the case of CSA communications, if a Chinese company has displayed more liberal corporate values in the past, an overt CSA message supporting same-sex marriage is likely to induce more violation expectedness. In addition, Afifi and Burgoon [58,71] also reported that in a series of experiments, participants rated a confederate as more attractive after the confederate performed certainty-increasing violating behaviors within the same valence. The experiments suggested that less unexpected violation behaviors served to increase relationship certainty. Meanwhile, the predictive power of the certainty-increasing behaviors within the same violation valence on the violator’s attractiveness was the strongest among several competing models. Based on the above evidence, this study hypothesizes that:

H4.

Violation expectedness is positively related to (a) relationship certainty and (b) organization–public relationships.

H5.

Relationship certainty mediates the effect of violation expectedness on organization–public relationships.

Earlier EVT studies have attempted to uncover the relationship between violation valence and relationship certainty. For example, White and Stewart [72] reported that positive violations were considered more informative than negative violations, thereby helping individuals reduce relationship uncertainty. Afifi and Metts [22] provided a holistic examination of relational quality in relation to violation valence and relationship certainty states after experiencing violation behaviors. The findings suggested that positively valenced violations were generally accompanied by decreased relationship uncertainty. Such uncertainty-reducing behaviors would further improve relational satisfaction, trust, closeness, commitment, and attraction. As OPR is also characterized by similar dimensions, such as commitment, satisfaction, and trust [56], it stands to reason that CSA communications that positively violate public expectancies could also serve to enhance relationship certainty and improve OPRs. In addition, EVT posits that positive violations of expectancies exert stronger positive influence on relationship quality than behaviors that conform to expectations [46]. Consistent with this assertion, Yim [73] measured the “pleasant surprise” effects of a CEO tweeting on political subjects and found that the tweets that positively violated public expectations engendered more positive reactions. Cho et al. [74] concurred that in corporate sustainability communication, positive expectancy-violating messages would lead to more favorable attitudes and stronger supportive intentions toward companies. In the corporate crisis communication context, Kim [50] found that negatively perceived violations can result in higher blame attributions for the violator (i.e., the company in crisis) for the resulting unfavorable outcomes and in more negative evaluations of the company. Contrarily, positively perceived violations should induce more positive evaluations of the company. Therefore, this study hypothesizes:

H6.

Positive violations are positively related to (a) relationship certainty and (b) organization–public relationships.

H7.

Relationship certainty mediates the effect of positive violations on organization–public relationships.

Authenticity constitutes the foundation of effective organizational communication, such as CSR [75,76]. From a public relations standpoint, authenticity refers to “having consistency between the inside and the outside of an organization” [77] (p. 5). It involves evaluation and perception of the genuineness, trustworthiness, credibility, and sincerity of the corporate communication or behavior [78]. Following Alhouti et al. [79], this study defines perceived CSA authenticity as genuine, stakeholder-oriented, less commercial, and beyond legal requirements. Researchers have found that the perceived authenticity of organizational communications has an impact on public attitudes, word-of-mouth intentions, and the evaluation of relationships with the organization [80,81]. Bogomoletc and Lee [82] suggested that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the frozen beef company Steak-Umm adopted a social media communication strategy that positively violated consumers’ expectancies, which resulted in overwhelmingly positive reactions. Through a semantic analysis of tweets, the authors found that the key to the success of Steak-Umm’s positive expectancy-violation strategy was consumers’ perceptions of the company’s authenticity [82,83]. Yim [32] also found that the positive expectancy violations triggered by the CEO’s political tweets were correlated with the perceptions of CEO authenticity. In addition, Lim and Young [84] found that the perceived authenticity of Ben & Jerry’s LGBTQ advocacy campaign significantly augmented the positive effects of CSA on corporate reputation ratings. Similarly, Lee and Kim [80] also found that employees’ perceptions of the authenticity of organizational behaviors could enhance organization–employee relationships. Thus, it is reasonable to infer that perceived authenticity can interact with violation valence to predict OPRs. Specifically, if Chinese companies’ CSA activities are perceived to be positive and authentic, the respondents will put down a higher evaluation on their relationships with the company.

H8.

Perceived authenticity moderates the effect of positive violation on organization–public relationships.

3. Method

To test the hypotheses, an 8 min online survey was administered on Qualtrics, with a sample drawn from Chinese consumers through an international research service company, Survey Sampling International (SSI; www.surveysampling.com, accessed on 29 December 2021). A stratified sampling technique was applied to recruit a sample of Chinese consumers that represents the gender and age composition of the Chinese population.

3.1. Sample

In total, 418 participants were retained for data analysis after initial data cleaning. The average age of all participants was 31.74 (SD = 9.23), ranging from 18 to 65. There were 244 (58.4%) males and 174 (41.6%) females. Among them, 21.1% of participants did not have a bachelor’s degree; 66.1% of participants had a bachelor’s degree; and 12.9% of participants had a graduate degree. In addition, 27% of the participants had homosexual family or friends, while only 4 participants reported their sexual orientation as homosexual, and 12 participants reported bisexual orientation.

The survey questionnaire was developed in English and translated by a native Chinese speaker into Chinese. Back translation was also conducted to ensure translation accuracy. Before administering the main study, a group of 9 scholars (4 English speakers and 5 Chinese speakers) pretested the questionnaire and offered feedback. During data collection, participants were first asked their issue advocacy and involvement level on the same-sex marriage issue. Then, they were randomly assigned to one of three conditions (corresponding to the different companies) and asked about their familiarity with and prior attitude towards the companies. The three companies were Xiami, an online music streaming app (comparable to Spotify), Youku, an online video streaming app (comparable to YouTube), and T-Mall, an e-commerce website/app (comparable to eBay). In all, 151, 121, and 146 participants were in the condition of T-Mall, Xiami, and Youku, respectively. Next, participants reported their predictive and prescriptive expectancies for the companies’ stances on the focal issue. Participants were then shown a screen shot of the real pro-same-sex-marriage CSA advertisement. Finally, questions on violation expectedness, violation valence, relationship certainty, OPR, and demographics were asked.

3.2. Measurement

All variables were measured with scales adapted from previous studies with a 9-point Likert scale or bipolar scale.

Issue advocacy was measured with six bipolar items, such as “I feel the legalization of same-sex marriage is bad/good” and “I feel the legalization of same-sex marriage is unfavorable/favorable” (α = 0.98; [85]). Issue involvement was measured with three items adopted from Kim and Grunig [86], such as, “I have a strong opinion about the legalization of same-sex marriage” (α = 0.98). The prior attitude towards the company was measured with five pairs of bipolar items, such as, “I feel that XXX is unappealing/appealing” (α = 0.98; [87]). C-C identification was also measured to gauge participants’ prior relationships with the companies, which were measured by five items adopted from Mael and Ashforth [88], e.g., “When someone criticizes the company, it feels like a personal insult” (α = 0.91).

Predictive expectancy and prescriptive expectancy measurements were both adopted from Kim [50] and Burgoon [47]. Specifically, predictive expectancy was measured with three items, such as, “I expect this company to clearly state its stance on the issue of same-sex marriage legalization” (α = 0.89). Prescriptive expectancy was measured with three items, such as, “I think Chinese companies should make a clear statement on the issue of same-sex marriage legalization” (α = 0.89).

Violation expectedness, violation valence, and relationship certainty were all adopted from Afifi and Metts [22]. Violation expectedness was measured with two items, including, “This CSA ad is completely expected from the company” and “This CSA ad surprised me a great deal” (reverse coded; α = 0.91). Violation valence was measured with 5 items, such as, “This CSA ad made me feel a lot better about the company,” and “This CSA ad is a very positive behavior from the company” (α = 0.97). Relationship certainty was measured with 4 items, including, “This CSA ad made me feel more confident in accurately predicting how this company will behave in the future,” and “This CSA ad made me feel more confident in accurately predicting the values that the company holds” (α = 0.96).

Perceived CSA authenticity was measured in terms of sustainability, accountability, transparency, genuineness, and visibility using 10 items adapted from Beckman et al. [75] and Beverland [78], such as, “The CSA ad is more than just a short-term business case for the company. It is likely to endure over time” (α = 0.96). Finally, the measurement of OPR was adopted from Ki and Hon [56] and measured in terms of control mutuality, trust, commitment, and satisfaction, using items such as, “The company believes the opinions of consumers like mine are legitimate,” and “Both the company and I benefit from our relationship” (α = 0.97).

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

Overall, the Chinese consumer sample revealed on average a neutral advocacy level (M = 4.83, SD = 2.28) and personal involvement level (M = 4.11, SD = 1.60) towards the social issue of same-sex marriage legalization. The skewness and kurtosis levels suggest that issue advocacy and involvement were normally distributed. Meanwhile, participants across three different conditions with different companies held similar prior attitudes to and C-C identification levels with the three different companies. An ANOVA test demonstrated non-significant results. Specifically, for prior attitude, F(2, 415) = 1.49, p > 0.1, MT-mall = 6.91, MXiami = 6.51, MYouku = 6.76; for C-C identification, F(2, 415) = 2.01, p > 0.1, MT-mall = 4.79, MXiami = 4.58, MYouku = 5.02. Participants from the three conditions were thus collapsed together to perform further data analysis.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed with SPSS Amos to test the model measurements. Based on the original model indexes and recommendation for modification, one of the measurement items from the predictive expectancy scale (i.e., “I expect this company to take a side on either supporting or opposing same-sex marriage”) and one from the prescriptive expectancy scale (i.e., “I need Chinese companies to be active in advocating for social issues, like same-sex marriage”) were dropped. The modified model fit results were satisfactory: chi-square = 421.77, df = 150, CMIN/df = 2.81, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97, NFI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.03, RMSEA = 0.06, PCLOSE > 0.05. See Table 1 for measurement scale item loadings.

Table 1.

Measurement and factor loadings.

Then, convergent and discriminant validity was further confirmed. First, convergent validity was checked with average variance extracted (AVE) and composite validity (CR). AVE values ranged from 0.75 (predictive expectancy) to 0.87 (OPR), which all exceeded the threshold value of 0.50. CR values ranged from 0.84 (prescriptive expectancy) to 0.97 (violation valence), which all exceeded the threshold value of 0.70. Then, discriminant validity was confirmed by comparing the square root of AVE to inter-construct correlations and by comparing AVE to maximum shared variance (MSV). Results suggested that all AVE values were greater than the corresponding MSV values and all variables’ square root of AVE values were greater than their inter-construct correlations. See the full details of convergent and discriminant validity results in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean, SD, correlations, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

4.3. SEM Assumption Tests and Model Fit

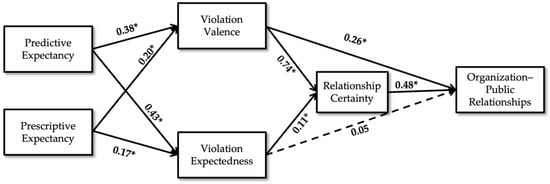

Following Kline [89], a series of underlying structural equation modeling assumptions were tested prior to testing the hypothesis. First, linearity for all proposed relationships in the model was examined with SPSS. The curve estimation tests determined all proposed relationships were sufficiently linear for structural equation modeling (SEM) testing. Second, outliers and influencers were examined with Cook’s distance. All test results suggested the Cook’s distances were less than 0.10. No outlier issue was detected. Third, multicollinearity tests suggested that the variance inflation factors (VIF) were all less than 2.0, with tolerance greater than 0.10. Lastly, multivariate normality was examined with Mardia’s coefficient in SPSS Amos. The critical ratio (c.r.) value was larger than 1.96, suggesting the sample data had significant positive multivariate kurtosis. To address this issue, bootstrapping (n= 2000 bootstrap samples) with maximum likelihood method was performed. The bootstrap results were consistent with those based on the normal theory. After the assumption test, SEM analysis was performed with SPSS Amos to test the proposed model and hypothesis. The SEM results revealed satisfactory model fit: chi-square = 9.93, df = 2, CMIN/df = 4.97, CFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.02, RMSEA = 0.08, PCLOSE > 0.05. Figure 1 demonstrates the final model and standardized estimates (β).

Figure 1.

Results of SEM analysis (* p < 0.01).

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

As shown in Figure 1, SEM results support both H1a and H1b. The stronger consumers’ predictive expectancies (β = 0.38, p < 0.01) and (b) prescriptive expectancies (β = 0.20, p < 0.01) towards Chinese companies’ CSA on same-sex marriage were, the more positively they perceived violations regarding the CSA message. Similarly, H2a and H2b were also supported. That is, stronger predictive expectancies (β = 0.43, p < 0.01) and prescriptive expectancies (β = 0.17, p < 0.01) increased consumers’ violation expectedness. Next, the direct effect of relationship certainty on organization–public relationships also appeared to be significant (β = 0.48, p < 0.01), supporting H3. Regarding H4, violation expectedness positively reinforced relationship certainty (β = 0.11, p < 0.01). Thus, H4(a) was supported. However, the direct relationship between violation expectedness and OPR was not significant (β = 0.05, p > 0.05). Therefore, H4(b) was not supported. Meanwhile, the direct effects of violation valence on relationship certainty (β = 0.74, p < 0.01) and OPR (β = 0.26, p < 0.01) were both significant and positive, so H6 was supported.

To test H5 and H7, two mediation analyses were performed with Hayes’ [90] SPSS PROCESS MODEL 4 to test relationship certainty’s mediation of the effects of violation valence and violation expectedness on organization–public relationships. Results suggest a partial mediation (B = 0.34, p < 0.01, 95% CI: 0.23, 0.45) by relationship certainty of the effect of violation valence. Therefore, H5 is supported. Full mediation was found for the effect of violation expectedness (B = 0.07, p > 0.05, 95% CI: −0.01, 0.14). Therefore, H7 was also supported.

Finally, H8 proposed that perceived authenticity moderates the effect of positive violations on organization–public relationships. This hypothesis was tested with Hayes’ [90] PROCESS MODEL 1. Violation valence, organization–public relationship, and perceived authenticity were entered as independent, dependent, and moderating variables, respectively. A bootstrap analysis with 5000 resamples was performed (F(3, 414) = 351.17, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.72). The coefficient for perceived authenticity (b) was −0.02, t(414) = −1.98, p < 0.05. The interaction was significant, but marginal (p = 0.048). However, further examination of the three perceived authenticity conditions (low vs. medium vs. high) revealed the effect of violation valence on organization–public relationship was significant in the same pattern across all conditions. That is, regardless of how authentic consumers felt the CSA message was, their violation valence had equal effects on their relationship with the company. Therefore, H8 was not supported.

5. Discussion

The findings here provide support for expectancy violations theory in the realm of CSA and help illuminate the role of violations of expectancies in relationships, particularly in relationships between organizations and publics. First, the results support past research findings that both predictive and prescriptive expectancies are important antecedents of the way unexpected corporate behaviors are interpreted and OPRs are evaluated [50,58]. Specifically, when consumers hold higher pre-existing expectations that companies in general and the specific companies of interest will engage in CSA efforts, they tend to have a lower level of unexpectedness as regards the companies taking real action and to perceive the CSA action more favorably.

Second, as predicted by the expectancy violations theory, consumers’ perceived certainty regarding their relationships with the company changes as a result of the unexpected corporate behavior. The direction of this change is predicted by the levels of perceived unexpectedness and valence of the violation. Investigation of expectancy violations in the CSA context supported Afifi and Metts’ [22] arguments that expectancy violations differ in their degree of severity and are not always negatively perceived. When the unexpected CSA communication is viewed favorably, that would strengthen the feeling of certainty about relationships with the company.

Third, this study confirms the link between relationship certainty and OPRs. Expectancy violations have usually been conceptualized as destabilizing relational events as they often arouse uncertainty, wherein violations negatively influence relational evaluations as compared to no-violation conditions [22,46,50,58]. This study sheds light on a less-explored situation, in which violations of expectancies increase relational certainty and positively impact the assessment of relationships.

Fourth, in response to Afifi and Burgoon’s [58] call for including the variance of uncertainty in full explanations of the expectancy violations’ effects on relationships, this study provides evidence that certainty is a key variable in the EVT model with OPRs as outcomes. The perceived relational certainty serves as a mediator explaining the mechanism underlying the association between the perception of the unexpectedness or the valence regarding the violations and the perception of OPRs. Specifically, the level of consumers’ certainty about their relationships with the companies accounts for some of the effects on OPRs of positively valenced violation, but fully transmits the effects of violation expectedness on OPR assessments. These results suggest that certainty is an important factor that bonds the relationship when an expectancy violation occurs. The violation may trigger an interpretation-evaluation process that assigns positive or negative value to the unexpected corporate behavior, but it is the feeling of certainty about the relationship that plays the key role in determining whether this interpretation–evaluation process leads to negative impacts on OPRs. These findings also lend weight to Afifi and Metts’ [22] endeavor to increase the EVT’s theoretical precision by introducing the concept of certainty borrowed from uncertainty-reduction theory [65].

Last, the proposed moderating effect of perceived authenticity is not supported. Unlike previous findings that perceived authenticity affects the re-evaluation of relationships with the company aroused by unexpected corporate communications or behaviors, all such interacting effects seem to be overshadowed by the significant main effect of violation valence itself. Additionally, sample selection effects represent another possible explanation. Unlike many previous studies that were conducted in the US and other Western countries, the current study used a Chinese sample. Different culture and business practices as well as variance in customer values are also a likely cause of these inconsistent findings.

The theoretical ramifications of this study merit attention. To begin with, this study is one of the first attempts to explore the strategic communication of corporate social advocacy in a non-Western context. Although CSA is a relatively new practice in China as compared with its development in the US, investigating Chinese consumers’ perception of this unconventional form of corporate engagement helps fill the research gap around CSA. Scholars trying to bring international perspectives to the field of public relations have highlighted the importance of political, economic, and societal contexts to public relations [91,92,93]. The findings of this study shed light on the inner workings of Chinese society and the subtle dynamic of mutual adjustment among business, government, and the public, laying a foundation for further investigation of how to maintain effective public relations in the country.

Additionally, extending the knowledge of EVT to CSA and OPR research presents a key opportunity for theory building in strategic communication and public relations. On one hand, EVT provides insights into consumers’ reactions to CSA communication and the consequent adjustment of the evaluation of OPRs. On the other hand, EVT is empirically supported in the realm of CSA communication, which enhances understanding of the role of expectations in stakeholders’ relationships with the companies. While researchers have examined various factors that may determine the effectiveness of CSA, including perceived congruence between the CSA stance and individuals’ stance on the issue [18,33], individuals’ issue involvement [18,25], attitudes toward CSA [3,94], and perceived congruence between corporate CSA stances and their actual actions [33], there have been few empirical examinations of individuals’ expectations of CSA itself. Yim [32] contended that it is the stakeholders’ expectations that ultimately shape the legitimacy of CSA behavior. This study enriches the understanding of expectations as an important factor in shaping individuals’ perceptions of CSA as well as the subsequent relational outcomes. The focus on expectations is also consistent with strategic issues management’s emphasis on managing stakeholder expectations and beliefs about the ways an organization should behave [28].

Furthermore, this study empirically tests a model of the effects of CSA communication on OPRs. As this study is among the initial attempts to establish the association between CSA communication and the outcome construct of OPR, it usefully furthering our understanding of public relationship management strategies and related theories as well.

These results point to some important practical considerations for public relations professionals engaged in CSA. At first glance, it may seem that companies should be cautious in selecting controversial issues to advocate for. As these results indicate, the same CSA communication may be perceived favorably by some and unfavorably by others. Consumers’ pre-existing expectations of companies in general, and of specific companies to engage in CSA around this particular issue, are important factors determining how CSA is received. Therefore, a company’s CSA-related decisions should be based on adequate research on stakeholder publics’ expectations. Moreover, as the perception of relationship certainty plays a key role in shaping OPR assessments when an expectancy violation occurs, the strategy that seems to work here entails having the CSA efforts help reaffirm publics’ certainty about the relationship with the company and the company’s future moves. In the same vein, revealing sincere motives, making long-term commitments, and communicating corporate values and authenticity around the company’s CSA efforts can help buffer the negative effects of negatively perceived violation of expectancies.

These recommendations may seem more cautious than those that scholars and practitioners suggest to companies in the US (e.g., [95]), as ours are drawn from findings in the Chinese context. Doing business in China requires understanding its institutional environment and moral idiosyncrasies, which can differ greatly from those of most Western liberal democratic societies [9,96]. It should be noted that issue salience may vary across countries. Some sociological issues that CSA engages in the US are not necessarily contentious and salient issues in another society. Like CSR, CSA should also take into consideration contextual factors [93,97]. A promising sign, however, is that CSA on the same-sex marriage issue could be positively received among Chinese consumers even though such behavior was unexpected. Moreover, Ramasamy et al.’s [97] study found that many consumers in China support companies that are socially responsible. This suggests that some parts of the country’s complex operating environment are becoming more receptive to social advocacy.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its contributions, the current study has several limitations. First, although structural equation modeling was used to test the proposed conceptual model, causality between the variables could not be fully established without experimentally examining the relationships between the endogenous and exogenous variables. Future studies could use longitudinal or experimental methods to corroborate these results. Second, the survey instruments featured three real Chinese companies and their CSA advertisements. Future experiments could consider employing fictitious companies to eliminate the confounding effects of prior attitudes and experience. Third, it can be inferred that participants’ own sexuality could be an important influencer in the context of the current study. However, out of 418 participants, only 4 participants self-reported as homosexual and 12 others self-reported as bisexual. Thus, the sample of the current study only contained 3.82% non-heterosexual participants, lower than the ratio of the homosexuals among the population found in previous academic research or public polls. It is possible that, under the influence of traditional Chinese culture, participants’ responses were strongly subject to social desirability bias. Nonetheless, the current study could not statistically include sexual orientation as a covariate. Future studies, though, could opt for non-self-reported measures to examine this question. Fourth, among the wide spectrum of corporate social advocacy, the current study focused solely on the issue of same-sex marriage legalization. Future research could examine CSA in general or further explore other important CSA issues in China. In addition, the current study focused on the Chinese market, which is less examined in terms of CSA communications. Future comparative studies could compare consumers from different geographical regions and cultural contexts regarding their expectancies of CSA to further reveal how EVT can be applied to explain global differences in CSA outcomes. Meanwhile, results regarding the effects of perceived authenticity in CSA communications contradicted previous research. Future studies could investigate the reasons for such inconsistent findings, especially regarding the meaning of CSA authenticity to Chinese consumers in comparison to Westerners. Last, future studies could contextually examine the cultural and political imperatives that shape Chinese consumers’ definitions and expectancies of CSA, which would further illuminate how the Westernized concept of CSA can be better adapted to the Chinese social–political environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S. and X.L.; methodology, B.S. and X.L.; validation, B.S. and X.L.; formal analysis, B.S.; investigation, B.S.; resources, B.S.; data curation, B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.S. and X.L.; writing—review and editing, B.S. and X.L.; visualization, B.S. and X.L.; supervision, B.S. and X.L.; project administration, B.S.; funding acquisition, B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Virginia Commonwealth University (Protocol code: HM20012154 and approval date: 18 January 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Wettstein, F.; Baur, D. “Why should we care about marriage equality?”: Political advocacy as a part of corporate responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, M.D.; Supa, D.W. Testing the viability of corporate social advocacy as a predictor of purchase intention. Commun. Res. Rep. 2015, 32, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, H.; Choi, M.; Weatherred, J.L.; Zhang, N. Testing the viability of emotions and issue involvement as predictors of CSA response behaviors. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2020, 48, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Qian, C. Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Symbol or substance? Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tang, L.; Li, H. Corporate social responsibility communication of Chinese and global corporations in China. Public Relat. Rev. 2009, 35, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Zhang, Y. Institutional dynamics and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in an emerging country context: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, G.P. Effective Public Relations in China. China Business Review, 2011. Available online: https://www.chinabusinessreview.com/effective-public-relations-in-china/ (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Hou, J.Z.; Zhu, Y. Social capital, guanxi and political influence in Chinese government relations. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J. Institutional structure and firm social performance in transitional economies: Evidence of multinational corporations in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, R. Taiwan Set to Legalize Same-Sex Marriages, a First in Asia. Associated Press News, 2016. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/e9c5b9c82abe4bc987f820aa104f2893 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Peng, K.; Rechdan, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, L.; Xin, Y.; Lin, J.; Duan, Z.; Zhu, X. Mapping out a spectrum of the Chinese public’s discrimination toward the LGBT community: Results from a national survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.; Zhang, A.; Yang, Y. Taiwan to allow gay marriage in first for Asia. Financial Times, 2017. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/06a8fb16-406b-11e7-9d56-25f963e998b2 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Chou, W.-S. Homosexuality and the cultural politics of Tongzhi in Chinese societies. J. Homosex. 2001, 40, 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.D. A Closer Look at Gay Rights in China. The Diplomat, 2017. Available online: https://thediplomat.com/2017/05/a-closer-look-at-gay-rights-in-china/ (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Jeffreys, E.; Wang, P. Pathways to legalizing same-sex marriage in China and Taiwan: Globalization and “Chinese values”. In Global Perspectives on Same-Sex Marriage: A Neo-Institutional Approach; Winter, B., Forest, M., Sénac, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, J. Alibaba Praised by China’s Gay Community for Ad Recognizing Same-Sex Couples. Reuters, 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-homosexuality-alibaba/alibaba-praised-by-chinas-gay-community-for-ad-recognizing-same-sex-couples-idUSKBN1Z80RN (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Malhotra, R. China’s Tech Companies back Marriage Equality. Tech in Asia, 2015. Available online: https://www.techinasia.com/chinas-tech-companies-marriage-equality (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Hong, C.; Li, C. To support or to boycott: A public segmentation model in corporate social advocacy. J. Public Relat. Res. 2020, 32, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lee, E.; Rim, H. Should businesses take a stand? Effects of perceived psychological distance on consumers’ expectation and evaluation of corporate social advocacy. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Jiang, H. Signaling, verification, and identification: The way corporate social advocacy generates brand loyalty on social media. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K. The mediating role of skepticism: How corporate social advocacy builds quality relationships with publics. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, W.A.; Metts, S. Characteristics and consequences of expectation violations in close relationships. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1998, 15, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, J.K.; Jones, S.B. Toward a theory of personal space expectations and their violations. Hum. Commun. Res. 1976, 2, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, J.K. Expectancy violations theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Interpersonal Communication; Berger, C.R., Roloff, M.E., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Browning, N.; Lee, E.; Park, Y.E.; Kim, T.; Collins, R. Muting or meddling? Advocacy as a relational communication strategy affecting organization–public relationships and stakeholder response. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 2020, 97, 1026–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalick, M.; Josefy, M.; Zardkoohi, A.; Bierman, L. Corporate sociopolitical involvement: A reflection of whose preferences? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 30, 384–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciszek, E.; Logan, N. Challenging the dialogic promise: How Ben & Jerry’s support for Black Lives Matter fosters dissensus on social media. J. Public Relat. Res. 2018, 30, 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Gaither, B.M.; Austin, L.; Collins, M. Examining the case of DICK’s sporting goods: Realignment of stakeholders through corporate social advocacy. J. Public Interest Commun. 2018, 2, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Tarasevich, S.; Proverbs, P.; Myslik, B.; Kiousis, S. President Trump vs. CEOs: A comparison of presidential and corporate agenda building. J. Public Relat. Res. 2020, 32, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcha, J.M.; Kingsley Westerman, C.Y. How corporate social advocacy affects attitude change toward controversial social issues. Manag. Commun. Q. 2020, 34, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Lee, Y.; Yoo, S. Polarized public opinion responding to corporate social advocacy: Social network analysis of boycotters and advocators. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, M.C. Fake, faulty, and authentic stand-taking: What determines the legitimacy of corporate social advocacy? Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2021, 15, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Dong, C. Matching words with actions: Understanding the effects of CSA stance-action consistency on negative consumer responses. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2021, 27, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, M.D.; Supa, D.W. Conceptualizing and measuring “corporate social advocacy” communication: Examining the impact on corporate financial performance. Public Relat. J. 2014, 8, 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, M.A. Building theory in public relations: Interorganizational relationships as public relations paradigm. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Gainesville, FL, USA, 5 August 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hon, L.C.; Grunig, J.E. Guidelines for Measuring Relationships in Public Relations; Institute for Public Relations: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ledingham, J.A.; Bruning, S.D. Relationship management in public relations: Dimensions of an organization-public relationship. Public Relat. Rev. 1998, 24, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ji, Y. Chinese Consumers’ expectations of corporate communication on CSR and sustainability. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 570–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Guo, L. Chinese “Tongzhi” community, civil society, and online activism. Commun. Public 2016, 1, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cao, J.; Lu, X. A preliminary exploration of the gay movement in mainland China: Legacy, transition, opportunity, and the new media. Signs: J. Women Cult. Soc. 2014, 39, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Yang, K.C.C. Gay and lesbian blogs in China: Rhetoric of reversed silence in cyberspace. China Media Res. 2009, 5, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Banik, D.; Lin, K. Business and morals: Corporate strategies for sustainable development in China. Bus. Politics 2019, 21, 514–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Horton, N. Chinese Businesses Eye Purchasing Power of LGBT Community. Market Watch, 2015. Available online: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/chinese-businesses-eye-purchasing-power-of-lgbt-community-2015-03-19 (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Chiu, J. China’s New Multibillion-Dollar Target Market: LGBT Youth. Foreign Policy, 2017. Available online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/02/27/chinas-new-multibillion-dollar-target-market-lgbt-youth/ (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Bielinski, S. 250 Business Leaders Attend 3rd China LGBT “Pink Market” Conference. Xin Wen Gao, 2016. Available online: https://www.xinwengao.com/pr/201611181048344217/250-business-leaders-attend-3rd-china-lgbt-pink-market-conference/ (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Burgoon, J.K. Interpersonal expectations, expectancy violations, and emotional communication. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 12, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, J.K.; Hale, J.L. Nonverbal expectancy violations: Model elaboration and application to immediacy behaviors. Commun. Monogr. 1988, 55, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, J.K.; Hubbard, A.S.E. Cross-cultural and intercultural applications of expectancy violations theory and interaction adaptation theory. In Theorizing about Intercultural Communication; Gudykunst, W., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 149–171. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, S.; Tolsdorf, J. How does corporate reputation affect customer loyalty in a corporate crisis? J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2013, 21, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. The role of prior expectancies and relational satisfaction in crisis. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2014, 91, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Burgoon, J.K. A communication model of personal space violations: Explication and an initial test. Hum. Commun. Res. 1978, 4, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Crisis management: Advantages of a relational perspective. In Public Relations as Relationship Management: A Relational Approach to the Study and Practice of Public Relations; Ledingham, J.A., Bruning, S.D., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ledingham, J.A. Explicating relationship management as a general theory of public relations. J. Public Relat. Res. 2003, 15, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olkkonen, L.; Luoma-Aho, V.L. Broadening the concept of expectations in public relations. J. Public Relat. Res. 2015, 27, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomlison, T.D. An interpersonal primer with implications for public relations. In Public Relations as Relationship Management: A Relational Approach to the Study and Practice of Public Relations; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 177–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ki, E.-J.; Hon, L.C. Reliability and validity of organization-public relationship measurement and linkages among relationship indicators in a membership organization. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 2007, 84, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, G.M.; Casey, S.; Ritchey, J. Toward a concept and theory of organization-public relationships. J. Public Relat. Res. 1997, 9, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, W.A.; Burgoon, J.K. The impact of violations on uncertainty and the consequences for attractiveness. Hum. Commun. Res. 2000, 26, 203–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, J.K.; Walther, J.B. Nonverbal expectancies and the evaluative consequences of violations. Hum. Commun. Res. 1990, 17, 232–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, L.K.; Solomon, D.H. Information seeking beyond initial interaction: Negotiating relational uncertainty within close relationships. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, L.K. Evaluating a contextual model of responses to relational uncertainty increasing events: The role of intimacy, appraisals, and emotions. Hum. Commun. Res. 2006, 31, 60–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, L.K.; Solomon, D.H. Relational uncertainty and relational information processing: Questions without answers? Commun. Res. 2005, 32, 349–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiss, J.A.; Solomon, D.H. Parsing the mechanisms that increase relational intimacy: The effects of uncertainty amount, open communication about uncertainty, and the reduction of uncertainty. Hum. Commun. Res. 2008, 34, 625–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreye, M.E. Relational uncertainty in service dyads. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, C.R.; Calabrese, R.J. Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: Towards a development theory of interpersonal communication. Hum. Commun. Res. 1975, 1, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Wang, Q. Anxiety and uncertainty management in an intercultural setting: The impact on organization–public relationships. J. Public Relat. Res. 2011, 23, 269–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, L.K.; Carpenter-Theune, K.E. Topic avoidance in developing romantic relationships: Associations with intimacy and relational uncertainty. Commun. Res. 2004, 31, 173–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planalp, S.; Honeycutt, J.M. Events that increase uncertainty in personal relationships. Hum. Commun. Res. 1985, 11, 593–604. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, C.R. Uncertainty and social interactions. In Communication Yearbook 16; Deetz, S.A., Ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 491–502. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.E.; Davis, K.E. From acts to dispositions the attribution process in person perception. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965; Volume 2, pp. 219–266. [Google Scholar]

- Afifi, W.A.; Burgoon, J.K. Behavioral violations in interactions: The combined consequences of valence and change in uncertainty on interaction outcomes. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Speech Communication Association, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–26 November 1996. [Google Scholar]

- White, C.H.; Stewart, R.A. Effects of expectancy violations on uncertainty in interpersonal interactions. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of Speech Communication Association, Chicago, IL, USA, 1–4 November 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yim, M.C. CEOs’ political tweets and perceived authenticity: Can expectancy violation be a pleasant surprise? Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Park, S.-Y.; Kim, S. When an organization violates public expectations: A comparative analysis of sustainability communication for corporate and nonprofit organizations. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, T.; Colwell, A.; Cunningham, P.H. The emergence of corporate social responsibility in Chile: The importance of authenticity and social networks. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilpin, D.R.; Palazzolo, E.T.; Brody, N. Socially mediated authenticity. J. Commun. Manag. 2010, 14, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, S.A.; Hung-Baesecke, C.-J.F.; Chen, Y.-R.R. Ethics as a precursor to organization–public relationships: Building trust before and during the OPR model. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 1141467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M. The ‘real thing’: Branding authenticity in the luxury wine trade. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhouti, S.; Johnson, C.M.; Holloway, B.B. Corporate social responsibility authenticity: Investigating its antecedents and outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, J.-N. Authentic enterprise, organization-employee relationship, and employee-generated managerial assets. J. Commun. Manag. 2017, 21, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Prado, P.H.M.; Korelo, J.C.; Frizzo, F. The effect of brand authenticity on consumer–brand relationships. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogomoletc, E.; Lee, N.M. Frozen meat against COVID-19 misinformation: An analysis of Steak-Umm and positive expectancy violations. J. Bus. Tech. Commun. 2021, 35, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, T.M. Meet the Minds behind the Bizarre, Truth-Bombing Steak-umm Twitter Account. The Washington Post, 2020. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/04/21/steak-umm-twitter-account-feed/ (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Lim, J.S.; Young, C. Effects of issue ownership, perceived fit, and authenticity in corporate social advocacy on corporate reputation. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, J.P.; Shen, L.; Vail, R.G. Does perceived message effectiveness cause persuasion or vice versa? 17 consistent answers. Hum. Commun. Res. 2007, 33, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-N.; Grunig, J.E. Problem solving and communicative action: A situational theory of problem solving. J. Commun. 2011, 61, 120–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, N.; Singh, S.N. Measuring attitude toward the brand and purchase intentions. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2004, 26, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, T. Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach to Design and Evaluation; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson, H.M.; Jeffers, D.W. The social, political, and economic contexts: Keys in educating true public relations professionals. Public Relat. Rev. 1992, 18, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunig, J.E.; White, J. The effect of worldviews on public relations theory and practice. In Excellence in Public Relations and Communication Management; Grunig, J.E., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 31–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sriramesh, K.; Verčič, D. A theoretical framework for global public relations research and practice. In The Global Public Relations Handbook: Theory, Research, and Practice; Sriramesh, K., Verčič, D., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.-Y.; Kim, J.K.; Alharbi, K. Exploring the role of issue involvement and brand attachment in shaping consumer response toward corporate social advocacy (CSA) initiatives: The case of Nike’s Colin Kaepernick campaign. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenti, P.A. When Should Your Company Speak Up About a Social Issue? Harvard Business Review, 2020. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/10/when-should-your-company-speak-up-about-a-social-issue. (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Snell, R.; Tseng, C.S. Moral atmosphere and moral influence under China’s network capitalism. Organ. Stud. 2002, 23, 449–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, B.; Yeung, M.C.; Chen, J. Selling to the urban Chinese in East Asia: Do CSR and value orientation matter? J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2485–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).