Linking CSR Communication to Corporate Reputation: Understanding Hypocrisy, Employees’ Social Media Engagement and CSR-Related Work Engagement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Effective CSR Communication Expected by Stakeholders

2.2. Key Dimensions of Effective CSR Communication

2.3. Benefits of Effective CSR Communication in Employee Relationships: From the Perspective of Social Exchange Theory (SET) and Signaling Theory

2.4. Employee CSR Engagement

2.4.1. CSR Work Engagement

2.4.2. CSR Social Media Engagement

2.5. CSR Communication and Employee Engagement

2.6. Corporate Reputation

2.7. Corporate Hypocrisy

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participant Profile

3.2. Measures

3.3. Model Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Data Analysis

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.2. Control Variables

4.2. Measurement Model Results

4.3. Structural Model Results and Hypothesis Testing

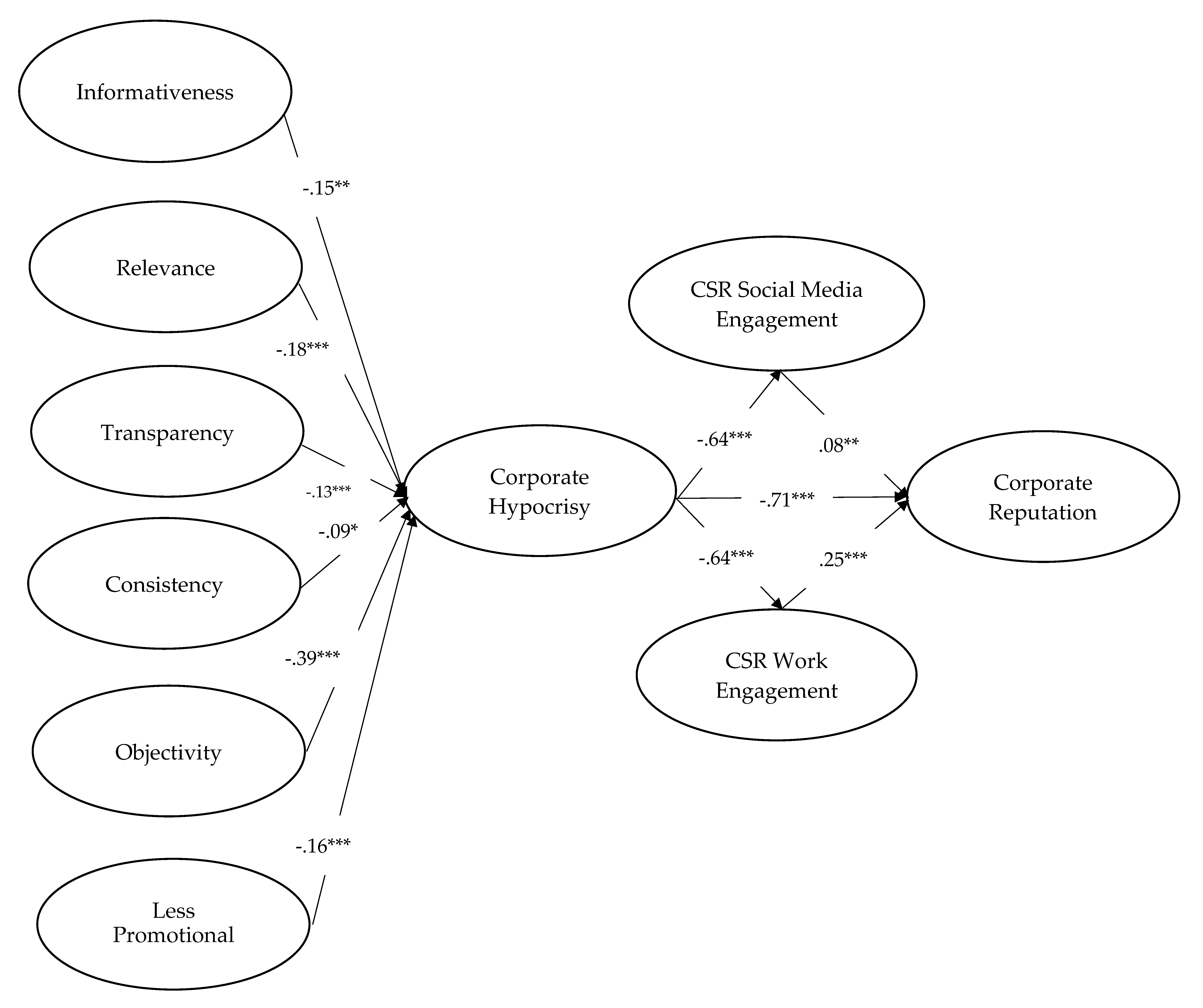

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werther, W.; Chandler, D. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Stakeholders in a Global Environment; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Ferguson, M.T. Public expectations of CSR communication: What and how to communicate CSR. Public Relat. J. 2014, 8, 1–22. Available online: https://www.bellisario.psu.edu/assets/uploads/2014KIMFERGUSON.pdf (accessed on 06 January 2022).

- Kim, S.; Ferguson, M.A.T. Dimensions of effective CSR communication based on public expectations. J. Mark. Commun. 2018, 24, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. The Process Model of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Communication: CSR Communication and its Relationship with Consumers’ CSR Knowledge, Trust, and Corporate Reputation Perception. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 1143–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Doing Better at Doing Good: When, Why, and How Consumers Respond to Corporate Social Initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, M.; Schultz, M. Corporate social responsibility communication: Stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, M.; Schultz, M.; Nielsen, K.U. The ‘Catch 22’ of communicating CSR: Findings from a Danish study. J. Mark. Commun. 2008, 14, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, C.-D.; Kim, J. The effects of CSR communication in corporate crises: Examining the role of dispositional and situational CSR skepticism in context. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate Hypocrisy: Overcoming the Threat of Inconsistent Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, J.S.; Greenwood, C.A. Communicating corporate social responsibility (CSR): Stakeholder responsiveness and engagement strategy to achieve CSR goals. Public Relat. Rev. 2017, 43, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Kim, S. Dimensions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) skepticism and their impacts on public evaluations toward CSR. J. Public Relat. Res. 2016, 28, 248–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-U. An Integrated Model for Organization—Public Relational Outcomes, Organizational Reputation, and Their Antecedents. J. Public Relat. Res. 2007, 19, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhu, W.; Zheng, X. Procedural Justice and Employee Engagement: Roles of Organizational Identification and Moral Identity Centrality. J. Bus. Ethic 2014, 122, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.; Yue, C.A. Status of internal communication research in public relations: An analysis of published articles in nine scholarly journals from 1970 to 2019. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.; Esteban, R. Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2007, 16, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.-T.; Kim, N.-M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee–Company Identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R. Why the PR strategy of storytelling improves employee engagement and adds value to CSR: An integrated literature review. Public Relat. Rev. 2015, 41, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Rehman, K.U.; Ali, S.I.; Yousaf, J.; Zia, M. Corporate social responsibility influences, employee commitment and organizational performance. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 2796–2801. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-R.R.; Hung-Baesecke, C.-J.F. Examining the Internal Aspect of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Leader Behavior and Employee CSR Participation. Commun. Res. Rep. 2014, 31, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, J.A.; Westerman, C.Y.K. Strengthening the Tie: Creating Exchange Relationships That Encourage Employee Advocacy as an Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Manag. Commun. Q. 2018, 32, 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-N.; Rhee, Y. Strategic Thinking about Employee Communication Behavior (ECB) in Public Relations: Testing the Models of Megaphoning and Scouting Effects in Korea. J. Public Relat. Res. 2011, 23, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek-Nowosielska, M.; Kuźmiński, Ł. CSR Level versus Employees’ Attitudes towards the Environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.S.; Wu, C.; Ullah, Z. The Inter-Relationship between CSR, Inclusive Leadership and Employee Creativity: A Case of the Banking Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, C.; Walter, C.; Sousa, B.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M.; Santos, V.; Valeri, M. Academic Tourism and Transport Services: Student Perceptions from a Social Responsibility Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Kim, H.; Woo, J. How CSR Leads to Corporate Brand Equity: Mediating Mechanisms of Corporate Brand Credibility and Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spence, M. Signaling in Retrospect and the Informational Structure of Markets. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 434–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korschun, D.; Bhattacharya, C.; Swain, S.D. Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Orientation, and the Job Performance of Frontline Employees. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duthler, G.; Dhanesh, G.S. The role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and internal CSR communication in predicting employee engagement: Perspectives from the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Maximizing Business Returns to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of CSR Communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Marques, T.; Mackie, D.M. The Feeling of Familiarity as a Regulator of Persuasive Processing. Soc. Cogn. 2001, 19, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Pollach, I. The Perils and Opportunities of Communicating Corporate Ethics. J. Mark. Manag. 2005, 21, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. Managing Corporate Social Responsibility; Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms; Harcourt: San Diego, CA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gould-Williams, J.; Davies, F. Using social exchange theory to predict the effects of HRM practice on employee outcomes. Public Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotsi, M.; Wilson, A.M. Corporate reputation: Seeking a definition. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2001, 6, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate Social Performance as a Competitive Advantage in Attracting a Quality Workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinen, S.; Harju, L. Volunteer Engagement: Exploring the Distinction between Job and Organizational Engagement. Voluntas 2017, 28, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work Engagement: A Quantitative Review and Test of Its Relations with Task and Contextual Performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, J.R.; Harter, J.K. Race Effects on the Employee Engagement-Turnover Intention Relationship. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2005, 11, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job Engagement: Antecedents and Effects on Job Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbard, N.P. Enriching or Depleting? The Dynamics of Engagement in Work and Family Roles. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 655–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-Romá, V.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.; Lloret, S. Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles? J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, M. The evolution of the employee engagement concept: Communication implications. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2011, 16, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.G.; Stumberger, N.; Guild, J.; Dugan, A. What’s at stake? An analysis of employee social media engagement and the influence of power and social stake. Public Relat. Rev. 2017, 43, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Sundar, S.S. User Engagement with Interactive Media: A Communication Perspective. In Why Engagement Matters: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives of User Engagement in Digital Media; O’Brien, H., Cairns, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer Brand Engagement Scale. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabash, S.; Baek, J.-H.; Cunningham, C.; Hagerstrom, A. To comment or not to comment? How virality, arousal level, and commenting behavior on YouTube videos affect civic behavioral intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, G.R.; Haddock, G. Attitude Change. In Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles; Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 565–586. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, R.E.; Corlett, S.; Morris, R. Exploring Employee Engagement with (Corporate) Social Responsibility: A Social Exchange Perspective on Organisational Participation. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kesavan, R.; Bernacchi, M.D.; Mascarenhas, O.A. Word of mouse: CSR communication and the social media. Int. Manag. Rev. 2013, 9, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Donath, J. Signals in Social Supernets. J. Comput. Commun. 2007, 13, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Tsai, W.-H.S. Infusing social media with humanity: Corporate character, public engagement, and relational outcomes. Public Relat. Rev. 2015, 41, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Habibi, M.R.; Richard, M.-O.; Sankaranarayanan, R. The effects of social media based brand communities on brand community markers, value creation practices, brand trust and brand loyalty. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1755–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Gardberg, N.A.; Sever, J.M. The Reputation QuotientSM: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. J. Brand Manag. 2000, 7, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K. A Systematic Review of the Corporate Reputation Literature: Definition, Measurement, and Theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2010, 12, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Stacks, D.W. The impact of leadership style and employee empowerment on perceived organizational reputation. J. Commun. Manag. 2013, 17, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Ali, M.; Grigore, G.; Molesworth, M.; Jin, Z. The moderating role of corporate reputation and employee-company identification on the work-related outcomes of job insecurity resulting from workforce localization policies. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 117, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puncheva-Michelotti, P.; Michelotti, M. The role of the stakeholder perspective in measuring corporate reputation. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2010, 28, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindova, V.P. Part VII: Managing Reputation: Pursuing Everyday Excellence: The image cascade and the formation of corporate reputations. Corp. Reput. Rev. 1997, 1, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Van Riel, C.B.M. The Reputational Landscape. Corp. Reput. Rev. 1997, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Van Riel, C.B.; Van Riel, C. Fame & Fortune: How Successful Companies Build Winning Reputations; Prentice-Hall Financial Times: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Ponzi, L.J.; Newburry, W. Stakeholder Tracking and Analysis: The RepTrak® System for Measuring Corporate Reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2015, 18, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romenti, S. Reputation and stakeholder engagement: An Italian case study. J. Commun. Manag. 2010, 14, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberle, D.; Berens, G.; Li, T. The Impact of Interactive Corporate Social Responsibility Communication on Corporate Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lii, Y.-S.; Lee, M. Doing Right Leads to Doing Well: When the Type of CSR and Reputation Interact to Affect Consumer Evaluations of the Firm. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.-Y.; Lee, H.J. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, K.; Yang, S.-U. The effect of bad reputation: The occurrence of crisis, corporate social responsibility, and perceptions of hypocrisy and attitudes toward a company. Public Relat. Rev. 2016, 42, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, Y.; Buelens, M. The hypocrisy-sincerity continuum in corporate communication and decision making. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarmeas, D.; Leonidou, C.N. When consumers doubt, Watch out! The role of CSR skepticism. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1831–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Gurhan-Canli, Z.; Schwarz, N. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Activities on Companies with Bad Reputations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rim, H.; Song, D. Corporate message strategies for global CSR campaigns. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2017, 22, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, Y.-J. The complex attribution process of CSR motives. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Grace, A.; Palmer, J.; Pham, C. Investigating the direct and indirect effects of corporate hypocrisy and perceived corporate reputation on consumers’ attitudes toward the company. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Gray Shades of Green: Causes and Consequences of Green Skepticism. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 144, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Cameron, G.T. Conditioning effect of prior reputation on perception of corporate giving. Public Relat. Rev. 2006, 32, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Zhou, J. Corporate Hypocrisy and Counterproductive Work Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model of Organizational Identification and Perceived Importance of CSR. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Babu, N.; De Roeck, K.; Raineri, N. Hypocritical organizations: Implications for employee social responsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Huang, L. Home-country institutions and corporate social responsibility of emerging economy multinational enterprises: The belt and road initiative as an example. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2020, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.C.; Boo, E. Organisational ethics and employee satisfaction and commitment. Manag. Decis. 2004, 42, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.; Irani, L.; Silberman, M.; Zaldivar, A.; Tomlinson, B. Who are the crowdworkers? Shifting demographics in Mechanical Turk. In Proceedings of the ACM CHI Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–15 April 2010; pp. 2863–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kees, J.; Berry, C.; Burton, S.; Sheehan, K. An Analysis of Data Quality: Professional Panels, Student Subject Pools, and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 7th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Chou, C.-P. Practical Issues in Structural Modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Yuan, Y.C.; McComas, K.A. Communal Risk Information Sharing: Motivations Behind Voluntary Information Sharing for Reducing Interdependent Risks in a Community. Commun. Res. 2018, 45, 909–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Rim, H. The Role of Public Skepticism and Distrust in the Process of CSR Communication. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, P. When Can You Safely Ignore Multicollinearity? Available online: https://statisticalhorizons.com/multicollinearity (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Cheng, Y.; Jin, Y.; Hung-Baesecke, C.-J.F.; Chen, Y.-R.R. Mobile Corporate Social Responsibility (mCSR): Examining Publics’ Responses to CSR-Based Initiatives in Natural Disasters. Int. J. Strat. Commun. 2018, 13, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Jin, Y.; Hung-Baesecke, C.-J.F.; Chen, Y.-R.R. When CSR meets mobile SNA users in mainland China: An examination of gratifications sought, CSR motives, and relational outcomes in natural disasters. Int. J. Commun. 2019, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

| Sample Characteristics | Valid n of Sample | Valid % of Sample |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 811 | 100.0% |

| Male | 376 | 46.4 |

| Female | 434 | 53.5 |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 0.1 |

| Age | 810 | 100.0% |

| Mean = 37.78; SD = 10.41 | ||

| Years with the Current Employers | 807 | 100.0% |

| Mean = 7.30; SD = 6.02 | ||

| Number of Subordinates | 801 | 100.0% |

| Mean = 26.62; SD = 352.85 | ||

| Ethnicity | 811 | 100.0% |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 640 | 78.9 |

| Hispanic American | 33 | 4.1 |

| African American | 66 | 8.1 |

| Native American | 4 | 0.5 |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 51 | 6.3 |

| Multicultural | 12 | 1.5 |

| Other | 5 | 0.6 |

| Organizational Size (Number of Employees) | 811 | 100.0% |

| Below 250 | 223 | 27.5 |

| Between 250 and 1000 | 202 | 24.9 |

| Between 1001 and 5000 | 124 | 15.3 |

| Between 5001 and 10,000 | 81 | 10.0 |

| Between 10,001 and 50,000 | 51 | 6.3 |

| Between 50,001 and 100,000 | 66 | 8.1 |

| More than 100,000 | 64 | 7.9 |

| Highest Level of Education | 811 | 100.0% |

| High school graduate | 141 | 17.4 |

| Bachelor’s | 455 | 56.1 |

| Master’s | 157 | 19.4 |

| Doctorate | 21 | 2.6 |

| Other | 37 | 4.6 |

| Level of Position | 811 | 100.0% |

| Top management | 27 | 3.3 |

| Middle-level management | 255 | 31.4 |

| Lower-level management | 236 | 29.1 |

| Non-management | 293 | 36.1 |

| Salary | 811 | 100.0% |

| Less than $10,000 | 14 | 1.7 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 20 | 2.5 |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 84 | 10.4 |

| $30,000–$39,999 | 122 | 15.0 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 123 | 15.2 |

| $50,000–$59,999 | 139 | 17.1 |

| $60,000–$69,999 | 99 | 12.2 |

| $70,000–$79,999 | 80 | 9.9 |

| $80,000–$89,999 | 44 | 5.4 |

| $90,000–$99,999 | 27 | 3.3 |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 44 | 5.4 |

| More than $150,000 | 15 | 1.8 |

| Alpha | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.92 | 5.03 | 1.22 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 0.95 | 4.65 | 1.57 | 0.66 ** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 0.95 | 4.15 | 1.52 | 0.48 ** | 0.57 ** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 0.76 | 5.05 | 1.11 | 0.40 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.26 ** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 0.89 | 5.27 | 1.16 | 0.59 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.46 ** | 1.00 | |||||

| 0.79 | 4.32 | 1.34 | 0.19 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.31 ** | 1.00 | ||||

| 0.94 | 2.88 | 1.27 | −0.57 ** | −0.59 ** | −0.53 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.64 ** | −0.39 ** | 1.00 | |||

| 0.95 | 4.54 | 1.47 | 0.47 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.31 ** | −0.59 ** | 1.00 | ||

| 0.98 | 5.63 | 1.05 | 0.51 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.20 ** | −0.52 ** | 0.55 ** | 1.00 | |

| 0.97 | 5.32 | 1.13 | 0.61 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.66 ** | 0.31 ** | −0.79 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.66 ** | 1.00 |

| One-Level Factor | Indicator | Standardized Loading | AVE/CR | |

| Informativeness | I believe my organization has been actively providing: | AVE = 0.64 CR = 0.91 | ||

| 0.76 *** | |||

| 0.82 *** | |||

| 0.80 *** | |||

| 0.83 *** | |||

| 0.82 *** | |||

| 0.75 *** | |||

| Relevance | My organization has actively informed me: | AVE = 0.87 CR = 0.95 | ||

| 0.93 *** | |||

| 0.95 *** | |||

| 0.91 *** | |||

| Transparency | I believe my organization: | AVE = 0.86 CR = 0.95 | ||

| 0.90 *** | |||

| 0.93 *** | |||

| 0.95 *** | |||

| Consistency |

| 0.78 *** | AVE = 0.49 CR = 0.73 | |

| 0.80 *** | |||

| 0.47 *** | |||

| Objectivity |

| 0.90 *** | AVE = 0.80 CR = 0.89 | |

| 0.89 *** | |||

| Less Promotional |

| 0.43 *** | AVE = 0.59 CR = 0.80 | |

| 0.82 *** | |||

| 0.95 *** | |||

| Corporate Hypocrisy | My organization | AVE = 0.73 CR = 0.94 | ||

| 0.86 *** | |||

| 0.88 *** | |||

| 0.87 *** | |||

| 0.81 *** | |||

| 0.88 *** | |||

| 0.82 *** | |||

| CSR Social Media Engagement |

| 0.72 *** | AVE = 0.68 CR = 0.94 | |

| 0.80 *** | |||

| 0.82 *** | |||

| 0.86 *** | |||

| 0.87 *** | |||

| 0.85 *** | |||

| 0.82 *** | |||

| 0.84 *** | |||

| First-Level Factor | Second-Level Factor | Indicator | Standardized Loading | AVE/CR |

| CSR Work Engagement (AVE = 0.80 CR = 0.92) | Physical Engagement (0.85 ***) | When I participate in a corporate social responsibility (CSR) program or initiative that my employer organizes or sponsors, | AVE = 0.79 CR = 0.96 | |

| 0.88 *** | |||

| 0.89 *** | |||

| 0.92 *** | |||

| 0.87 *** | |||

| 0.89 *** | |||

| 0.89 *** | |||

| Emotional Engagement (0.97 ***) | When I participate in a corporate social responsibility (CSR) program or initiative that my employer organizes or sponsors, | AVE = 0.78 CR = 0.96 | ||

| 0.89 *** | |||

| 0.87 *** | |||

| 0.89 *** | |||

| 0.88 *** | |||

| 0.90 *** | |||

| 0.88 *** | |||

| Cognitive Engagement (0.86 ***) | When I participate in a corporate social responsibility (CSR) program or initiative that my employer organizes or sponsors, | AVE = 0.76 CR = 0.95 | ||

| 0.86 *** | |||

| 0.87 *** | |||

| 0.90 *** | |||

| 0.82 *** | |||

| 0.92 *** | |||

| 0.85 *** | |||

| Corporate Reputation (AVE = 0.82 CR = 0.97) | Emotional Appeal (0.93 ***) |

| 0.93 *** | AVE = 0.8 5CR = 0.94 |

| 0.93 *** | |||

| 0.90 *** | |||

| Vision and Leadership (0.97 ***) |

| 0.85 *** | AVE = 0.67 CR = 0.86 | |

| 0.86 *** | |||

| 0.75 *** | |||

| Workplace Environment (0.99 ***) |

| 0.83 *** | AVE = 0.70 CR = 0.88 | |

| 0.87 *** | |||

| 0.81 *** | |||

| Products and Services (0.87 ***) |

| 0.81 *** | AVE = 0.71 CR = 0.91 | |

| 0.79 ** | |||

| 0.91 *** | |||

| 0.86 *** | |||

| Responsibility (0.94 ***) |

| 0.79 *** | AVE = 0.65 CR = 0.85 | |

| 0.75 *** | |||

| 0.87 *** | |||

| Financial Performance (0.72 ***) |

| 0.71 *** | AVE = 0.60 CR = 0.85 | |

| 0.67 *** | |||

| 0.83 *** | |||

| 0.86 *** | |||

| Data-Model Fit | CFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.043 (C.I.: 0.041–0.044); SRMR = 0.04; χ2= 5781.77 ***; df = 2359; χ2/df = 2.45; n = 795 | *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01 | ||

| Structural Equation Model (Direct Effects) | BC 95% CI | ||||

| Paths | Estimate | S.E. | Z | Lower | Upper |

| H1a: Informativeness→Hypocrisy (supported) | −0.15 | 0.05 | −2.82 ** | −0.26 | −0.05 |

| H1b: Relevance→Hypocrisy (supported) | −0.18 | 0.05 | −3.89 *** | −0.28 | −0.09 |

| H1c: Transparency→Hypocrisy (supported) | −0.13 | 0.04 | −3.62 *** | −0.20 | −0.06 |

| H1d: Consistency→Hypocrisy (supported) | −0.09 | 0.05 | −1.75 * | −0.19 | 0.01 |

| H1e: Objectivity→Hypocrisy (supported) | −0.39 | 0.06 | −6.52 *** | −0.50 | −0.27 |

| H1f: Less promotional→Hypocrisy (supported) | −0.16 | 0.03 | −5.23 *** | −0.22 | −0.11 |

| H2: Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement | −0.64 | 0.03 | −19.15 *** | −0.70 | −0.57 |

| H3: Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement | −0.64 | 0.03 | −19.20 *** | −0.71 | −0.57 |

| H4: Hypocrisy→Reputation | −0.71 | 0.04 | −18.22 *** | −0.79 | −0.63 |

| H5: CSR social media engagement→Reputation | 0.08 | 0.03 | 2.60 ** | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| H6: CSR work engagement→Reputation | 0.25 | 0.04 | 6.62 *** | 0.18 | 0.33 |

| Control Variables | BC 95% CI | ||||

| Paths | Estimate | S.E. | Z | Lower | Upper |

| Size →Informativeness | 0.08 | 0.03 | 2.86 ** | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| Level of position→Informativeness | −0.08 | 0.03 | −2.86 ** | −0.14 | −0.03 |

| Level of position→Relevance | −0.18 | 0.03 | −6.05 *** | −0.24 | −0.12 |

| Level of position→Transparency | −0.11 | 0.03 | −3.62 *** | −0.17 | −0.05 |

| Age→Consistency | 0.08 | 0.04 | 2.38 * | 0.02 | 0.15 |

| Age→Objectivity | 0.13 | 0.03 | 4.81 *** | 0.08 | 0.19 |

| Age→Less promotional | 0.09 | 0.04 | 2.65 ** | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| Level of position→CSR social media engagement | −0.15 | 0.03 | −4.71 *** | −0.21 | −0.09 |

| Salary→ CSR social media engagement | −0.08 | 0.03 | −3.09 ** | −0.14 | −0.03 |

| Mediation Analysis | BC 95% CI | ||||

| Paths | Estimate | S.E. | Z | Lower | Upper |

| Hypocrisy as mediator: | |||||

| Informativeness→Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement | 0.10 | 0.04 | 2.78 ** | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| Relevance→Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement | 0.12 | 0.03 | 3.74 *** | 0.06 | 0.18 |

| Transparency→Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement | 0.08 | 0.02 | 3.55 *** | 0.04 | 0.13 |

| Consistency→Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1.73 * | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| Objectivity→Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement | 0.25 | 0.04 | 6.41 *** | 0.17 | 0.32 |

| Less promotional→Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement | 0.10 | 0.02 | 5.02 *** | 0.06 | 0.14 |

| Informativeness→Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement | 0.10 | 0.04 | 2.73 ** | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| Relevance→Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement | 0.12 | 0.03 | 3.76 *** | 0.06 | 0.18 |

| Transparency→Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement | 0.08 | 0.02 | 3.64 *** | 0.04 | 0.13 |

| Consistency→Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1.69 * | 0.00 | 0.12 |

| Objectivity→Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement | 0.25 | 0.04 | 6.54 *** | 0.17 | 0.32 |

| Less promotional→Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement | 0.10 | 0.02 | 5.22 *** | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| Informativeness→Hypocrisy→Reputation | 0.11 | 0.04 | 2.76 ** | 0.03 | 0.19 |

| Relevance→Hypocrisy→Reputation | 0.13 | 0.03 | 3.78 *** | 0.06 | 0.20 |

| Transparency→Hypocrisy→Reputation | 0.09 | 0.02 | 3.66 *** | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Consistency→Hypocrisy→Reputation | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.75 * | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| Objectivity→Hypocrisy→Reputation | 0.27 | 0.05 | 5.95 *** | 0.19 | 0.37 |

| Less promotional→Hypocrisy→Reputation | 0.11 | 0.02 | 5.02 *** | 0.07 | 0.16 |

| Engagement as mediator: | |||||

| Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement→Reputation | −0.05 | 0.02 | −2.63 ** | −0.09 | −0.01 |

| Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement→Reputation | −0.16 | 0.03 | −6.01 *** | −0.22 | −0.11 |

| Hypocrisy and engagement as joint mediators: | |||||

| Informativeness→Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement→Reputation | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.92 * | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Informativeness→Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement→Reputation | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.51 * | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Relevance→Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement→Reputation | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2.16 * | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Relevance→Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement→Reputation | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.19 * | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Transparency→Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement→Reputation | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2.09 * | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Transparency→Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement→ Reputation | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.89 * | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Objectivity→Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement→Reputation | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.39 * | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Objectivity→Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement→Reputation | 0.06 | 0.01 | 4.76 *** | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Less promotional→Hypocrisy→CSR social media engagement→Reputation | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2.35 * | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Less promotional→Hypocrisy→CSR work engagement→Corporate reputation | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.97 *** | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Factors | R-Square Estimate | S.E. | Z | ||

| Corporate hypocrisy | 0.70 | 0.03 | 28.62 *** | ||

| CSR social media engagement | 0.44 | 0.04 | 10.75 *** | ||

| CSR work engagement | 0.41 | 0.04 | 9.61 *** | ||

| Corporate reputation | 0.89 | 0.02 | 51.43 *** | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Park, K.; Zhu, W. Linking CSR Communication to Corporate Reputation: Understanding Hypocrisy, Employees’ Social Media Engagement and CSR-Related Work Engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2359. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042359

Jiang H, Cheng Y, Park K, Zhu W. Linking CSR Communication to Corporate Reputation: Understanding Hypocrisy, Employees’ Social Media Engagement and CSR-Related Work Engagement. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2359. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042359

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Hua, Yang Cheng, Keonyoung Park, and Wei Zhu. 2022. "Linking CSR Communication to Corporate Reputation: Understanding Hypocrisy, Employees’ Social Media Engagement and CSR-Related Work Engagement" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2359. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042359

APA StyleJiang, H., Cheng, Y., Park, K., & Zhu, W. (2022). Linking CSR Communication to Corporate Reputation: Understanding Hypocrisy, Employees’ Social Media Engagement and CSR-Related Work Engagement. Sustainability, 14(4), 2359. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042359