The Influence of Institutional Support on the Innovation Performance of New Ventures: The Mediating Mechanism of Entrepreneurial Orientation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

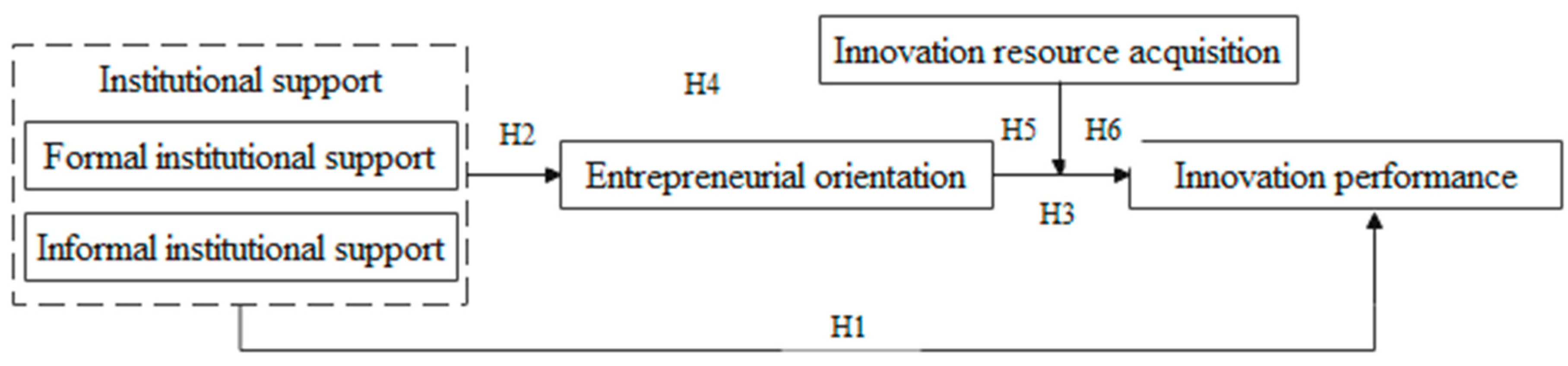

2. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Institutional Support and Innovation Performance of New Ventures

2.2. Institutional Support and Entrepreneurial Orientation

2.3. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Innovation Performance of New Ventures

2.4. The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation

2.5. The Moderating Role of Innovative Resource Acquisition

3. Research Method

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Acquisition

3.2. Sample Statistics

3.3. Measurement

3.4. Reliability and Validity Analysis

3.5. Common Method Deviation Test

4. Research Results and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.2. Direct Effect Test

4.3. Mediating Effect Test

4.4. Moderating Effect Test

4.5. Test of Moderated Mediation Effects

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nambisan, S.; Siegel, D.; Kenney, M. On open innovation, platforms, and entrepreneurship. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Carvajal, O.; García-Pérez-De-Lema, D. Innovation capability and open innovation and its impact on performance in smes: An empirical study in chile. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 2150039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, H. How to bridge the gap between innovation niches and exploratory and exploitative innovations in open innovation ecosystems. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile-Lüdecke, S.; De Oliveira, R.T.; Paul, J. Does organizational structure facilitate inbound and outbound open innovation in SMEs? Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 55, 1091–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, B.G.; Blair, E.S.; Lohrke, F.T. Developing a scale to measure liabilities and assets of newness after start-up. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 10, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.T.; Nelson, R. Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 329–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addas, S.; Pinsonneault, A. IT capabilities and NPD performance: Examining the mediating role of team knowledge processes. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2016, 14, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. International entrepreneurial marketing strategies of MNCs: Bricolage as practiced by marketing managers. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frese, T.; Geiger, I.; Dost, F. An empirical investigation of determinants of effectual and causal decision logics in online and high-tech start-up firms. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 54, 641–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjielias, E.; Dada, O.L.; Cruz, A.D.; Zekas, S.; Christofi, M.; Sakka, G. How do digital innovation teams function? Understanding the team cognition-process nexus within the context of digital transformation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A.; Stopa, M. SMEs innovativeness and institutional support system: The local experiences in qualitative perspective. Polish case study. Oeconomia Copernic. 2018, 9, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D.; Vural, C.A. Embedding social innovation process into the institutional context: Voids or supports. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 119, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crupi, A.; Del Sarto, N.; Di Minin, A.; Phaal, A.; Piccaluga, A. Open innovation environments as knowledge sharing enablers: The case of strategic technology and innovative management consortium. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servajean-Hilst, R.; Donada, C.; BenMahmoud-Jouini, S. Vertical innovation partnerships and relational performance: The mediating role of trust, interdependence, and familiarity. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 97, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Yoo, J. How does open innovation lead competitive advantage? A dynamic capability view perspective. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Xu, G.; Zhou, Y.; Miao, Z. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firms’ Innovation in China: The Role of Institutional Support. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Byun, G.; Ding, F. The Direct and Indirect Impact of Gender Diversity in New Venture Teams on Innovation Performance. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Opoku, R.; Frimpong, K. Entrepreneurs’ improvisational behavior and new venture performance: Firm-level and institutional contingencies. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 83, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Howe, M.; Kreiser, P.M. Organisational culture and entrepreneurial orientation: An orthogonal perspective of individualism and collectivism. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2019, 37, 125–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Zhang, S. Multiple strategic orientations and strategic flexibility in product innovation. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schøtt, T.; Jensen, K.W. Firms’ innovation benefiting from networking and institutional support: A global analysis of national and firm effects. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1233–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, K.K.; Pearce, J.L. Guanxi: Connections as substitutes for formal institutional support. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1641–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Tellis, G.J.; Prabhu, J.C.; Chandy, R.K. Radical Innovation across Nations: The Preeminence of Corporate Culture. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henard, D.H.; Szymanski, D.M. Why some new products are more successful than others. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Wang, Q.; Gao, S.; Liu, C. Firm Patenting, Innovations, and Government Institutional Support as a Double-Edged Sword. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J. Innovation and risk-taking in a transitional economy: A comparative study of Chinese managers and entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag. Sci. 1983, 7, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, B.A.; Mai, N.T.T.; Minh, N.H. Informal institutions and entrepreneurial orientation: An exploratory investigation into Vietnamese small and médium enterprises. J. Econ. Dev. 2018, 20, 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtulmuş, B.E.; Warner, B. Informal institutional framework and entrepreneurial strategic orientation: The role of religion. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2016, 20, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Chen, X.; Dong, M.C.; Gao, S. Institutional support and firms’ entrepreneurial orientation in emerging economies. Long Range Plan. 2021, 102106, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, R.C.; Moura-Leite, R.C. Innovation with High Social Benefits and Corporate Financial Performance. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2012, 7, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaki, H.; Jory, S.R. Institutional investors’ ownership stability and firms’ innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 103, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, P.; Song, M.; Ju, X. Entrepreneurial orientation and performance: Is innovation speed a missing link? J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtulmuş, B.E.; Katrinli, A.; Warner, B. International Entrepreneurial Orientation and Performance of SMEs: The Mediating Role of Informal Institutional Framework. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, H.; Imamoglu, S.Z.; Karakose, M.A. Entrepreneurial orientation, social capital, and firm performance: The mediating role of innovation performance. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2021, 683199960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Miles, M.P. Corporate entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive advantage. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1999, 23, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F. From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.; Adomako, S.; Mole, K.F. Perceived institutional support and small venture performance: The mediating role of entrepreneurial persistence. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2021, 39, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; De Clercq, D.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C. Government institutional support, entrepreneurial orientation, strategic renewal, and firm performance in transitional China. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, Z.; Heavey, C. The mediating role of knowledge-based capital for corporate entrepreneurship effects on performance: A study of small- to medium-sized firms. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2011, 5, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Atuahene-Gima, K. Product innovation strategy and the performance of new technology ventures in china. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Jin, J. Entrepreneurial orientation and innovation performance: Roles of strategic HRM and technical turbulence. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2015, 53, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y. The impact of entrepreneurial orientation on the acquisition of new enterprise resources. Res. Sci. Sci. 2011, 29, 601–609. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Qi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Pawar, K.S. Effects of business and political ties on product innovation performance: Evidence from China and India. Technovation 2019, 80–81, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhuo, S. The effects of institutional quality and diversity of foreign markets on exporting firms’ innovation. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasiah, R.; Shahrivar, R.B.; Yap, X.-S. Institutional support, innovation capabilities and exports: Evidence from the semiconductor industry in Taiwan. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 109, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filiou, D.; Golesorkhi, S. Influence of Institutional Differences on Firm Innovation from International Alliances. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, N.F.; Ordaz, C.C.; Dianez-Gonzalez, J.P.; Sousa-Ginel, E. The Role of Social and Institutional Contexts in Social Innovations of Spanish Academic Spinoffs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, I.S.; Ali, S.; Bhatti, S.H.; Anser, M.K.; Khan, A.I.; Nazar, R. Dynamic common correlated effects of technological innovations and institutional performance on environmental quality: Evidence from East-Asia and Pacific countries. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 124, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.; Clauss, T.; Issah, W.B. Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture performance in emerging markets: The mediating role of opportunity recognition. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almodóvar-González, M.; Fernández-Portillo, A.; Díaz-Casero, J.C. Entrepreneurial activity and economic growth. A multi-country analysis. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2020, 26, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Index | Attribute | Sample | Percentage (%) | Index | Attribute | Sample | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of business | Less than 1 year | 26 | 9.35 | type | Production Industry | 44 | 15.83 |

| 1–3 years | 101 | 36.33 | Trading Industry | 23 | 8.27 | ||

| 3–6 years | 132 | 47.48 | IT Industry | 183 | 65.83 | ||

| 6–8 years | 19 | 6.83 | other | 28 | 10.07 | ||

| Size | Less than 30 people | 34 | 12.23 | Annual sales revenue (million yuan) | Less than 5 | 54 | 19.42 |

| 31–100 people | 80 | 28.78 | 500–1000 | 79 | 28.42 | ||

| 101–300 people | 96 | 34.53 | 1000–5000 | 98 | 35.25 | ||

| More than 300 people | 68 | 24.46 | More than 5000 | 47 | 16.91 |

| Variables | Items | Loading | KMO | AVE | CR | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal institutional support FIS | The government has issued policies or projects that are conducive to the development of enterprises, etc. | 0.748 | 0.859 | 0.552 | 0.896 | 0.863 |

| The government provides information and technical support. | 0.715 | |||||

| The government provides assistance for our business to obtain financial support. | 0.755 | |||||

| The government provides assistance for our enterprises to introduce technology and equipment. | 0.783 | |||||

| The government provides direct financial subsidies for our companies. | 0.772 | |||||

| The government encourages companies to protect intellectual property rights. | 0.733 | |||||

| The government provides legal support for our companies to enter new markets. | 0.686 | |||||

| Informal institutional support IIS | We actively implement measures to establish relationships with government departments at all levels. | 0.870 | 0.691 | 0.742 | 0.897 | 0.786 |

| We have connections with multiple levels of government. | 0.835 | |||||

| Our relationship with government departments is very important for business development. | 0.806 | |||||

| Entrepreneurial orientation EO | Our company tends to market with mature products and services. | 0.727 | 0.828 | 0.505 | 0.890 | 0.784 |

| We have not developed new products and services in the past year. | 0.665 | |||||

| We do not make major adjustments to the combination of products and services. | 0.757 | |||||

| Faced with competitive behavior initiated by competitors, we are often forced to deal with. | 0.739 | |||||

| In the face of competition initiated by competitors, we will not preemptively introduce new products or services. | 0.762 | |||||

| In the face of competition initiated by competitors, we seek peaceful development. | 0.633 | |||||

| Our management team likes low-risk projects. | 0.687 | |||||

| When faced with uncertainties, we like to take cautious actions. | 0.703 | |||||

| Innovation resource acquisition IRA | We can quickly discover the effect of new external knowledge on existing technologies. | 0.679 | 0.775 | 0.522 | 0.867 | 0.759 |

| We can quickly acquire the technology and knowledge needed in the process of new product development. | 0.700 | |||||

| We can quickly acquire the experience, skills and knowledge needed for market development. | 0.768 | |||||

| We have extensive social network resources. | 0.771 | |||||

| We can obtain funds through external financing. | 0.694 | |||||

| We can obtain important industry information from the outside. | 0.718 | |||||

| Innovation performance IP | In the past three years, the company’s sales from new products/services have continued to rise. | 0.688 | 0.839 | 0.572 | 0.889 | 0.832 |

| In the past three years, the technical capabilities of enterprise product/service development and innovation have been improved. | 0.745 | |||||

| The success rate of the company’s new product/service development has continued to increase in the past three years. | 0.713 | |||||

| The improvement and innovation of enterprise products/services in the past three years has a good market response. | 0.767 | |||||

| Companies can launch new products/services faster than their competitors in the past three years. | 0.829 | |||||

| The market share of the company’s new products has continued to increase in the past three years. | 0.786 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 FIS | 0.743 | |||||||

| 2 IIS | 0.508 ** | 0.861 | ||||||

| 3 EO | 0.270 *** | 0.353 *** | 0.711 | |||||

| 4 IRA | 0.411 ** | 0.456 ** | 0.604 ** | 0.723 | ||||

| 5 IP | 0.498 ** | 0.702 ** | 0.598 ** | 0.678 ** | 0.756 | |||

| 6 Age | 0.050 | 0.063 | 0.047 | 0.087 | 0.006 | 1 | ||

| 7 Size | 0.096 | 0.087 | −0.091 | 0.022 | 0.052 | 0.434 ** | 1 | |

| 8 Turnover | 0.053 | −0.030 | −0.026 | 0.065 | −0.107 * | 0.061 | 0.017 | 1 |

| Mean | 4.689 | 4.535 | 4.681 | 4.515 | 4.560 | 2.77 | 2.79 | 2.02 |

| SE | 1.018 | 1.177 | 0.813 | 0.778 | 0.951 | 1.120 | 1.135 | 0.680 |

| Variables | IP | EO | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | |

| FIS | 0.200 *** (2.723) | 0.147 ** (2.331) | 0.283 ** (3.228) | |||||

| IIS | 0.600 *** (8.173) | 0.485 *** (7.459) | 0.293 ** (2.982) | |||||

| EO | 0.612 *** (8.419) | 0.394 *** (6.704) | 0.222 * (2.338) | 0.163 * (1.709) | ||||

| IRA | 0.532 *** (5.611) | 0.612 *** (6.265) | ||||||

| EO × IRA | 0.174 ** (2.573) | |||||||

| Age | −0.014 (−0.136) | −0.035 (−0.498) | −0.080 (−0.996) | −0.074 (−1.223) | −0.086 (−1.203) | −0.094 (−1.336) | 0.109 (1.081) | 0.098 (1.045) |

| Size | 0.060 (0.594) | −0.002 (−0.034) | 0.144 * (1.785) | 0.065 (1.069) | 0.100 (1.382) | 0.089 (1.259) | −0.137 (−1.368) | −0.171 * (−1.820) |

| Turnover | −0.107 (−1.180) | −0.097 (−1.538) | −0.089 (−1.230) | −0.087 (−1.605) | −0.133 * (−2.042) | −0.104 (−1.622) | −0.030 (−0.330) | −0.027 (−0.319) |

| R2 | 0.014 | 0.531 | 0.382 | 0.661 | 0.524 | 0.568 | 0.018 | 0.161 |

| Adj-R2 | −0.010 | 0.512 | 0.362 | 0.644 | 0.513 | 0.531 | −0.006 | 0.125 |

| F | 0.588 | 26.770 *** | 18.417 *** | 38.105 *** | 51.095 ** | 22.759 *** | 0.748 | 4.516 ** |

| Path | Coefficient Est. | SE | Bias-Corrected 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIS-EO-IP | 0.135 | 0.056 | 0.028 | 0.252 |

| IIS-EO-IP | 0.120 | 0.041 | 0.050 | 0.209 |

| Variables | Inspection Level | Coefficient | SE | Bias-Corrected 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRA (−1SD) | 0.021 | 0.037 | −0.050 | 0.101 | |

| FIS | IRA (+1SD) | 0.079 | 0.036 | 0.019 | 0.162 |

| Moderated mediation effects | 0.038 | 0.022 | 0.007 | 0.095 | |

| IRA (−1SD) | 0.026 | 0.036 | −0.047 | 0.098 | |

| IIS | IRA (+1SD) | 0.071 | 0.030 | 0.022 | 0.137 |

| Moderated mediation effects | 0.030 | 0.018 | 0.003 | 0.073 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.; Yu, M. The Influence of Institutional Support on the Innovation Performance of New Ventures: The Mediating Mechanism of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042212

Yang J, Yu M. The Influence of Institutional Support on the Innovation Performance of New Ventures: The Mediating Mechanism of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042212

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jie, and Mingxing Yu. 2022. "The Influence of Institutional Support on the Innovation Performance of New Ventures: The Mediating Mechanism of Entrepreneurial Orientation" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042212

APA StyleYang, J., & Yu, M. (2022). The Influence of Institutional Support on the Innovation Performance of New Ventures: The Mediating Mechanism of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Sustainability, 14(4), 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042212