Abstract

This study examines tourist trust in a government-initiated tourism brand from the perspective of the economic sustainability of the tourism industry. Its antecedents comprise traveler visit motivation, visitor experience perception, and willingness to visit/revisit, and the study assesses the moderating role of believers/nonbelievers in developing a tourism brand. The data were obtained from 20 notable religious-themed attractions listed among the “100 Religious Attractions” in Taiwan. Self-administered questionnaires were distributed to respondents who had visited, or were planning to visit, the listed attractions. Three hundred and eighty-five valid questionnaires were collected with the hypotheses developed and examined using the SEM method. This study analyzes the motivational and experiential differences between religious-oriented and ordinary visitors to the “100 Religious Attractions” and its brand effect concerning peripheral industry consumption behavior (e.g., food and beverage, religious items, and surrounding sightseeing sites). Last, this study discloses that the willingness to visit/revisit determinants, service value perception, and spiritual experience significantly affect tourism brand trust. These results offer a better understanding for both scholars and practitioners of religious-themed attractions regarding how tourists’ visit/revisit intentions and their willingness to consume affect the creation of tourism destination brand trust that is sustainable.

1. Introduction

Religious-themed tourism is growing in popularity, providing considerable value for in-depth discussion of tourism participants. Given the increasing socioeconomic significance of this vibrant field of the world’s leisure industry, religious-themed travel also contributes toward developing a sustainable tourism environment and affects the development of subsequent related policies. For sustainable tourism development, UNWTO provides a clear definition, as follows: “Tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, and the environment and host communities.”.

In addition to being integrated with people and the natural environment, tourism also contributes to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the purpose of which is to “eliminate poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all” by 2030. Thus, gaining knowledge of religious-themed scene attendees and their psychological views is essential for academicians and tour group organizers [1,2,3,4]. Religious and secular spheres of tourism are quickly emerging, as religious tourism assumes a more prominent market niche in international tourism [5,6,7]. Moreover, several reasons exist for the global revival of religious pilgrimage and tourism. These include culture learning, the rise of spirituality, a growing share of older people, media coverage regarding sacred sites and events, globalization of the local through mass media, seeking peace and solace in an increasingly turbulent world, and the availability of affordable flights to important religious tourism destinations [8,9,10,11].

Previous religious-themed tourism studies have featured such aspects as visiting religious ceremonies and conferences; visiting local, regional, national, and international religious centers; and social or group tours, which occur as extended family tourism or as club tourism through the integration of tourists into the travel group [12,13,14]. However, the essence of religious-themed tourism still cannot be separated from “pilgrimage”, which has been defined as “a journey resulting from religious causes, externally to a holy site, and internally for spiritual purposes and internal understanding” [15]. Smith deems that the term “pilgrimage” connotes a religious journey or a pilgrim’s journey, especially to shrines or sacred places [16]. Mosques, churches, cathedrals, pilgrimage paths, sacred architecture, and the lure of the metaphysical are used prominently in tourism literature, as evidenced in advertising efforts with religious connotations [17,18]. Because of marketing and an increased general interest in cultural tourism, religious sites are being frequented more by curious tourists than by spiritual pilgrims and are thus commodified and packaged for a tourism audience [19,20,21,22,23,24]. The same can be said of mass gathering memorial events, such as Great and Holy Friday in Christianity, Eid al-Fitr in Muslim, or Vesak Day in Buddhism. Many people travel to a widening variety of sacred sites for religious or spiritual purposes or to experience the sacrosanct in traditional ways. Such sites are marked and marketed as heritage or cultural attractions for consumption [23].

Today, most researchers do not distinguish between pilgrims and tourists or pilgrimage and tourism. Instead, a pilgrimage is typically accepted as a form of tourism [25,26,27,28], exhibiting many similar characteristics regarding travel patterns and transportation, services, and infrastructure. Tourism promotion is becoming critical in changing religious sites into tourist places because the symbolic meaning of the place can be transformed from a space of worship and contemplation into a scenic spot worthy of attention.

The challenges, constraints, and opportunities of the external and internal environments inherent in marketing a tourism destination differ from individual tourism service businesses. Destination marketers must create and manage a compelling and focused market position for their multi-attributed location, across multiple geographic markets, in a dynamic macro environment [29]. Therefore, destinations and destination marketing have emerged as a central element of tourism research [30,31,32,33], perhaps even “the fundamental unit of analysis in tourism” [34], because most tourism activity occurs at destinations [35,36,37].

Many package tours and regional attractions emphasize historical heritage characteristics as the selling point. Amid these sightseeing spots, religious or cultural themes are indispensable to connotation, such as the São Paulo Cathedral in Brazil, Angkor Wat in Cambodia, the Great Pyramids in Egypt, Notre-Dame de Paris in France, the Parthenon temple in Greece, Duomo di Milano in Italy, or the Hajj in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. At the same time, these spots also play a role in their inherent culture and precious cultural heritage in the world. Furthermore, tourism development has gradually transformed their vast economic potential into a solid industry due to the fascinating features of these remarkable scenic areas. In short, these notable religious sites or events have become a significant brand in global destination tourism. However, given that the viewpoints involved in this study are mainly economic, the following discussion explores how tourism brands can establish and maintain their tourists’ trust from the perspective of sustainable economic development.

Customizing the features of a destination to appeal to individual customer’s preferences presents greater challenges than for other manufactured products or services. Consequently, branding destinations have become more critical in the tourism industry [38,39]. Religious heritage or ceremonies require a period to accumulate brand awareness; however, research is limited regarding visitors’ attitudes toward public tourism sector-initiated new religious-themed brands. This paper tries to fill this gap in the literature by exploring tourists’ experiences with a government-initialed tourism brand project of religious attractions, their effect on their motivation, perception, intention to visit/revisit, and consumer willingness and purpose. This research investigates the association between the perception of the area with a tourist’s heritage and behavior to understand individual attitudes toward destination tour sites’ perceived image, brand awareness, and revisit intention. The above research gap led to the definition of four primary objectives from the perspective of sustainable economic development, as follows:

- (1)

- Explore the link between tourists’ post-trip perception and their pre-tour motivations;

- (2)

- Observe whether visit motivation and passenger perception are related to willingness to visit/revisit;

- (3)

- Examine whether the visitor’s willingness to visit/revisit can be transformed into trust in the new tourism brand initiated by the public tourism sector;

- (4)

- Verify whether the tourists visiting religious attractions have religious beliefs that exert a specific influence and difference in terms of forming trust in the tourism brand.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, we introduce the research object—a newly launched government-initialed religious-themed tourism brand, “100 Religious Attractions”—and review the literature on the relationship between visit motivation, visitor perception, and tourists’ willingness to visit/revisit. More importantly, this article observes tourists’ perceptions and willingness to spend on the commercial atmosphere in religious attractions and expounds on whether this perception and willingness can be translated into trust in tourism brands. Second, we describe the research method and present the main results of the tested model. Finally, we discuss the theoretical and managerial implications of the study, its limitations, and possible directions for future research.

2. Conceptual Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Study Object

Although Taiwan is a relatively small island located in the western Pacific Rim, it has various and energetic religious-cultural gatherings because of the close geographical distance and historical development with mainland China. Religions in Taiwan belong to the identical cultural circle and philosophical thought, and they are syncretized and pantheistic [40,41]. The island has persevered with the essentials of Chinese traditional folklore belief, providing good conditions for developing religious tourism.

Given the development of a local cultural tourism brand, the Taiwan Authority of Internal Affairs focused on the “100 Religious Attractions” selection campaign in 2013, which promoted island-wide religious-themed sites on the world stage. Meanwhile, the “Temple Stay in Taiwan” activity was launched for driving the development of other industries, such as local characteristics products/services, accommodation, exhibition, event, festival, public transportation, and theme tourism providers. The list of 100 attractions was selected according to three primary judgment criteria of “historical and cultural values”, “artistic and creative performance”, and “leisure and tour features.” Twenty-one experts and more than 1.5 million netizens voted on a preliminary list of 417 sites [42]. The list covered all significant religious belief institutes and events across the region, including folklore belief (Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism), Christianity, Islamic, and Indigenous inherent festivals. Table 1 illustrates the 100 religious sightseeing heritage and events in Taiwan.

Table 1.

Category of the list of the 100 religious’ attractions in Taiwan.

Nonetheless, this study does not involve discussions on “historical and cultural values”, “artistic and creative performance”, “leisure and tour features”, or other environmental development viewpoints. Rather, the economics of brand development is taken as a starting point because the existing research in the context of this religious-themed tourism promotion follow-up brand effect remains scarce. Therefore, understanding such phenomena is critical given the popularity of religious tourism and the fierce competition among destinations to attract potential visitors. Consequently, this study conducted a survey investigating potential travelers’ visit motivation and experienced visitor perception on the “100 Religious Attractions.” Additionally, to understand tourists’ willingness to visit or revisit, exploring whether such a desire to travel can help the “100 Religious Attractions” become a solid tourism brand. It is essential to understand whether believers and nonbelievers have different views on establishing the tourism brand.

2.2. Travel Motives in Religious Tourism

The literature review shows that different motivation elements determine satisfaction after the experience [43,44,45]. Specific purposes determine tourists’ choices of destinations and activities, and one key factor is tourists’ desires, which largely drive their perceived travel necessity [46,47]. Tourist motivation reflects a tourists’ internal dynamic needs, referred to as a push factor. Conversely, a pull factor influences tourists’ enjoyment of attraction in a specific tourism destination [48]. Motivation is a complex construct that controls customers’ attitudes, beliefs, and emotions [49], and it is essential to re-examine visitors’ travel motivation to improve the marketing of tourist attractions driven by religion [50]. For example, Rainisto [51] provides an integral four-step framework for maintaining the brand trust and suggests that the tourism sector build a strong relationship marketing to any stakeholder parties at religious tourism, as follows:

- The fundamental services must be well-prepared and offered, and infrastructure maintained to satisfy citizens, businesses, and visitors.

- A place may need new attractions to sustain current business and public support and bring in new investment, corporations, or people.

- A place needs to communicate its features and benefits through an impressive image and communication program.

- A place must generate support from citizens, leaders, and institutions to attract new investments.

In addition, to analyze the characteristics of religious tourism and its stakeholders regarding the customer’s features, Cohen [52] investigated the religious tourism market and its characteristics and classified four kinds of tourists to religious travel destinations, e.g., (1) seekers who aim to visit religious and secular tourist sites; (2) lotus-eaters who intend to visit only secular tourist sites; (3) pilgrims who intend to visit only spiritual tourist sites; and (4) accidental tourists who aim at visiting neither type of tour spot.

Therefore, this research clarifies the tourists’ motivations for visiting religious-themed attractions regarding attraction/event awareness, public sector promotion, and spiritual experience.

2.2.1. Attraction/Event Awareness

In terms of destination branding, awareness means the brand’s presence in the mind of the target tourists. The image represents the perceptions attached to the destination, quality that is concerned with perceptions of the quality of a destination’s attributes, and value, which is the tourists’ holistic evaluation of the benefit of a product in tourist destinations. Finally, loyalty represents the level of attachment to the tour destination, visit/revisit intention, positive word-of-mouth, and recommendation to others [53]. Yang and Lau verified children’s experiential educational benefits through engagement at world heritage site locations [54]. They found that a site’s reputation significantly stimulated children’s travel motivation and improved their learning. In addition, tourist destinations’ characteristics are essential in attracting tourists. For example, San Martín Island has become a great tourist attraction in Bangladesh, and it has recently become a site of economic growth due to tourism. However, the natural environment and ecosystem are deteriorating at an alarming rate. The local government lacks comprehensive planning to maintain the carrying capacity and restrict tourism activities, reducing tourists’ motivation to visit [55].

Kucukergin and Gürlek suggest that visiting disappearing attractions before they are gone has motivated some tourists [56]. For instance, Fo Guang Shan, a representative Buddhism pilgrimage site in Taiwan, was briefly closed between 1997 and 2000 to achieve quietness as a place for religious practice. Tens of thousands of believers from all walks of life poured into Fo Guang Shan early in the morning, hoping to personally participate in the final moments of the site’s closure [57]. Thus, the site itself can be important to consider concerning the perceived expressive and instrumental attributes and their influence on visitor satisfaction [58].

2.2.2. Public Sector Promotion

Destination marketing is a fundamental tool in promoting places; it must be present in local government strategies, helping and promoting the regions’ sustainable economic and social development [59]. The public sector has gradually relaxed previous restrictions and allowed local government departments to develop local tourism to improve the regional tourism industry. At the same time, through outsourcing and other methods, some private enterprises with sufficient qualifications were allowed to operate local tourist attractions [60]. In addition, the public sector also plays a leading role in comprehensively advertising tourist attractions; for example, the Malaysian government has introduced many Muslim-friendly tourism initiatives to attract Muslim tourists [61,62]. Samori, Salleh, and Khalid pointed out that Halal tourism is a new phenomenon that emerged from the Halal industry’s growth [63]. As Halal matters advance the tourism industry, many Muslim countries are set to capture the Muslim tourist market by providing tourism products, facilities, and infrastructure. Furthermore, the Russian government has started promoting new domestic destinations and actively supporting the industry. Still, the government needs to implement more effective organizational, legal, and tax-accounting measures [64]. On the official regional website for tourists, many tourist value propositions are available for different target audiences interested in religious, gastronomic, cultural and historical, business, family, active, wellness, agricultural, and eco-tours. There are also multimedia thematic maps that help potential visitors plan and raise awareness about local tourist objects.

The public sector has also begun to realize the importance of using the Internet and social software, which have become essential tools for publicizing and communicating tourist destinations and brands. Tsimonis and Dimitriadis deem that organizations can forge relationships with customers and form communities that interactively collaborate to identify problems and develop solutions by utilizing social media [65]. In this respect, social media can establish relations with users, understand their images and necessities, allow comments and participation/interaction, and communicate destination brands effectively. A large part of the global population is connected through online social networks, where they share experiences and stories and influence each other’s perceptions and buying behavior. This poses a distinct challenge for public sector-initiated destination management organizations, who must cope with a new reality: destination brands and storytelling in social networks are increasingly products of people’s shared tourism experiences rather than marketing strategies [66].

2.2.3. Spiritual Experiencing

Experience is arguably the reason for the popularity of spiritual tourism among novices and those who wish to develop and deepen transcendent engagement through and during travel. If spirituality is the goal, traveling seems like an ideal setting for searching and, sometimes, even discovering. The religious motivation of spiritual tourism mainly reflects connections with religion. At the same time, it centers on specific driving factors emphasized by religious rituals, ritualized practices, identity, and cultural expressions. [67]. Jiang, Ryan, and Zhang researched “meditation” in Buddhism and found that many non-Buddhists visit Buddhist attractions [68]. If the itinerary arranges the meditation, many visitors also enjoy it and feel a unique spiritual experience. In other words, the tourist context of separation from daily life, the landscape values of the locations, the temple atmosphere, the sharing of experiences with like-minded individuals, and contact with monks and mentors all contribute to the participant’s sense of personal wellness.

Religious-themed tourism mostly covers tourist trips to perform, visit, or practice religious heritages, ceremonies, or subsidiary activities. Travelers tend to visit the spiritual site and try to find meaning in a religious-themed tour [69,70,71]. For instance, a non-Catholic visitor may light a white candle and pray to the Father, the Son (Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit (as “one God in three Divine Persons”) in a cathedral. A non-Chinese folklore attendee may place their hands together or grip a burning incense stick to worship the Buddha or the Deity in a temple. This kind of performance as an orthodox prayer behavior is an integral part of the journey, and a respectful performance of the beliefs of different cultures will not lose or detract from the morality and solemnity of the faith itself. For instance, interactive visual media play a dominant role within religious scripts/doctrines, similar to theatrical scenarios. Determining the nature of performances or encounters in spiritual tourism can establish meanings related to sacred places and routines. This religious ceremony can also be the primary motivation for attracting visitors [72].

While studies debate the differences between “tourist” and “pilgrim”, and their motivations for visiting sacred destinations [73,74], they exhibit many of the same characteristics, behaviors, and expectations [75]. Cordina, Gannon, and Croall found that some like-minded groups, typically people with similar interests in religion, sports, or music, have a sense of belonging through interactions [76]. Therefore, the motivation for some tourists is that the trip itself provides the opportunity to meet new people. Pilgrimage is a setting that brings travelers of similar beliefs together for the same purpose: the motivation to undertake shared experiences and get to know fellow travelers [77].

2.3. Destination Perceptions in Religious Tourism

Tourists’ perceptions of a destination are built on associations in their memories [78]. Furthermore, people can obtain information from friends and acquaintances or post-trip blogs written by other visitors. Recent studies indicate that many tourists enjoy sharing knowledge, emotions, and experiential moments in online communities [79,80]. Some studies suggest that word-of-mouth is a meaningful way to shape destination image [81]. Visitors’ experiences can be affected by many factors in religious places, and these influencing factors further impact visitors’ perceptions of sacred tourism sites [82].

Poria, Reichel, and Cohen found that respondents believe that once religious scenic spots are listed in more prestigious rankings, they will potentially trigger tourism growth; however, such growth is unlikely to be converted to higher tourism demand. The appearance, design, circulation planning of the scenic spots (including the surrounding environment), and the magnitude of the follow-up advertising are key factors [83]. Palau-Somer et al. based on a multi-group analysis of visitors to the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, found that the emotions expressed by the service staff and the flow configuration of the cathedral building visit affected the mood of the visitors, which in turn affected their satisfaction and behavioral intention [84].

2.3.1. Acceptance of Commercial Activity

Religious tourism attractions integrate spiritual and secular characteristics. This paragraph will discuss three aspects from the visitor’s perspective: the acceptance of commercial activities, the received satisfaction, and service value perception.

While tourism is seen in many circles to contribute to preserving heritage and religious sites and bolstering sagging economies, it can be a destructive force in cultural unity and degradation of the natural and built environment. Some scholars are ambivalent about the negative impacts of tourism on religious sites because of the economic benefits [85]. There have been discussions about how Buddhist monks allow their religious festivals to be interrupted by tourists because of the potential revenue [86,87]. These examples parallel a comment by Fleischer and Felsenstein, who argue that the economic impacts of religious tourism are more significant than other market segments because pilgrims and other spiritual travelers avidly buy religious souvenirs [25]. Huang and Pearce researched China’s two primary sacred religious sites, Mount Wutai and Mount Jiuhua, with many traditional buildings, statues, and historical stories. They found that tourists believed that Taihuai Town in Wutai Mountain had more convenient modern infrastructure conditions, with many shops, restaurants, and hotels. However, the same tourists felt it was over-commercialized, which detracted from the spiritual nature [8].

In light of the dual motivations of leisure and religious tourists, the lack of a valid instrument to measure participants’ motivation will undermine the effectiveness of business operations and potentially disenfranchise guests. Furthermore, to some degree, the commercialization of religious sites driven by economic growth can potentially influence tourist behavior [2]. In short, commercializing religion could affect tourist satisfaction and their perceived value of a sacred journey [88,89,90]; excessive commercial behavior will harm the sustainable development of religious tourism. Therefore, further study is needed to establish whether emerging commercial activities at religious sites affect tourist motivations. When travelers are aware of over-commercialization and if religious attractions feel “more businesslike”, the perceived service values will be undermined.

The regional tourism sector and religious organizers are usually open to such a phenomenon; however, we intend to verify whether the common trend of religious commercialization will harm holy sites or travelers’ perceptions.

2.3.2. Received Satisfaction

Past studies have mainly examined consumer behavior and adopted managerial perspectives, emphasizing the outcomes of negative tourists’ emotions toward suppliers. Particular attention has been paid to the impact of negative emotions on tourists’ satisfaction and intentional behavior, indicating the unfavorable consequences of negative emotions. Prayag et al. found that feeling disappointment, unhappiness, regret, and negative perceptions could decrease overall satisfaction [91,92]. Such tourists would be disinclined to recommend and provide positive word-of-mouth for other world heritage sites. Breitsohl and Garrod found that those who develop hostile emotions (such as anger, satisfaction, and disgust) for specific events are more likely to spread negative word-of-mouth and be less likely to revisit the destination [93].

Satisfaction also varies according to the travelers’ characteristics. Medeiros et al. surveyed tourists visiting the Azores and found that the conditions for accommodation varied by gender. Visitors of different ages had different satisfaction with flight times, housing, medical, and operational requirements. Additionally, language difficulty, cultural differences, medical care, travel prices, and mobility conditions varied according to passengers. The perception of one’s health status also changes during the stay, depending on the destination’s safety, the comfort level of accommodation, food tastes, cultural differences, mobility conditions, and hospitality. Fulfillment with travel varies according to satisfaction with life and perception of health [94]. Medina-Viruel et al. analyzed the motivation and satisfaction of tourists who visited the monumental ensembles of the World Heritage cities of Spain’s Úbeda and Baeza. The results highlight a shared cultural identity among nearby tourists—the identity of the Andalusian Renaissance—and suggest a high level of tourist satisfaction with a primarily artistic motivation for visiting the destination. Whether the purpose of the visit is achieved will affect tourist satisfaction [95].

2.3.3. Service Value Perception

Satisfaction is a sensed condition; one evaluates perceptions formed from an outcome against prior expectations [96]. More specifically, satisfaction is a judgment regarding one’s contentment with a service value perception. Service quality, value, and customer satisfaction have previously been identified as essential consumer behavior precursors [97,98,99,100]. Lovelock indicated that perceived value is a trade-off among customers’ perceived outlays and gains [101]. As such, value is intrinsic to the customer; it is an overall perception of a good or service in meeting requirements relative to what is provided. In Lai‘s study on restaurant hospitality, the service value perceptions were impacted positively by improved service quality [100].

Similarly, in tourism research on the quality-value-satisfaction-loyalty paradigm in beach tourism, Hasan et al. showed that service quality and perceived value are related to the destination image, tourist attitudes, and satisfaction degree has a direct impact. In addition, destination image and satisfaction significantly affect the mood and loyalty of tourists [102].

Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1.

Tourists’ visit motivation has a significant and positive influence on visitors’ perception of the “100 Religious Attractions”.

2.4. Willingness to Visit/Revisit

Willingness to visit/revisit is generated from positive destination images [103]; people usually decide to visit a destination because they have exciting and pleasant images of the place. Middleton and Clarke believe that potential tourists consider travel comprehensively, including tangible and intangible components and the question of whether they have sufficient travel funds. The research also listed five important aspects for analyzing how tourists consider potential destinations: attractions and environment, facilities and services, convenience, image, and price [104].

Amid numerous efforts to explore religious tourists’ willingness to visit/revisit a site or event, some scholars attempted to determine whether most pilgrims travel to spiritual places due to sufficient attractions. The level of tourists’ loyalty is often measured by their willingness to visit or intention to revisit and their supportive behavior for a destination [105]. Achieving high customer loyalty is a primary goal for most businesses, including tourism destinations. Nyaupane et al. found that three groups of tourists visiting holy places had mixed expectations of the educational, religious, recreational [106], and social benefits [107]. For scaling the motivations, previous studies have provided some support for a factor-based structure delineating the motivations of religious tourists [108,109,110,111]. Overall satisfaction is viewed as an evaluative judgment of the last purchase occasion. Based on all encounters with the service provider, transaction-specific satisfaction is likely to vary between experiences. In contrast, overall satisfaction is a moving average that is relatively stable and most like a general attitude toward purchasing a brand [112,113,114,115,116]. Therefore, this study views consumer satisfaction as a consumer’s overall emotional response (visit motivation and visitor perception) to the entire trip expectation and experience for a single transaction before and after purchasing.

Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2.

Tourists’ visit motivation has a significant and positive influence on the willingness to visit “100 Religious Attractions”.

Hypothesis 3.

Tourists’ experience perception has a significant and positive influence on the willingness to revisit “100 Religious Attractions”.

2.5. Tourism Brand Trust

Religious attractions play a role in location branding, and obtaining the benefits of religious-based tourism will be more accessible from a marketing perspective [117,118]. A brand needs time to build from initial establishment to comprehensive visibility. Thus, integrating marketing communications involve mixing and matching different communication options to establish the desired awareness and image in consumers’ minds [119]. Some efforts leading to consensus on measurement include shortening the distance between the tourism site brand from the owner’s side and the customer, based on Aaker [120] and Keller’s [121] categorization [122]. For instance, Yang et al. integrate the aforementioned concepts—destination brand awareness, destination image, destination brand quality, and destination brand loyalty—as tourism marketing indicators [123]. This is vital because different customers have different perceptions about the same destination. Hence, it is imperative to understand, at an integrated level, how the visitors’ experience, through direct or indirect contact with the destination, affects tourism marketing practices.

Many tourism researchers regard destination image as a multidimensional construct of destination brand equity. Among these discussions, the significant indicators are awareness, appearance, quality, and loyalty [124,125,126]. The attributes that could persuade tourists to visit a destination include the natural and historical background, rich heritage, lodging facility, and climate [127]. The more awareness a tourist has of the location’s positive features, the more reliable their cognitive evaluation [128].

Previous studies have defined brand awareness as reflecting the tourist’s knowledge of a particular destination or the presence of a destination in the tourist’s mind when considering a given travel context [129]. Brand image, often interchangeably referred to as brand associations, represents the associations attached to the destination, composed of various individual perceptions relating to multiple attributes that may or may not reflect the destination’s objective reality [130]. Brand quality is a holistic judgment based on excellence or overall superiority [131]. Satisfaction is a tourist’s cognitive-affective state derived from their experience at the destination [132]. Finally, loyalty represents the core dimension of brand equity [119]. In tourism, loyalty is usually considered the intention to revisit the destination and word-of-mouth intentions [133,134].

Among these significant indicators, brand awareness plays a crucial role in consumers’ buying decision-making process. In tourism marketing, brand awareness is the extent to which consumers are familiar with the distinctive qualities or image of a particular brand of goods or services [119]; it includes individual recognition, knowledge dominance, and recall of brands [17]. Brand awareness is how individuals become informed and accustomed to a brand name and recognize the brand [135,136,137]. Awareness is distinguished in two dimensions: intensity and extent. The intensity of brand awareness indicates how effortlessly consumers recall a particular brand in tourism marketing. The extent of brand awareness refers to the possibility of acquiring and consuming brand services and products in a sightseeing spot [138], especially when the brand emerges in consumers’ minds [139]. Travel brands need to retain the dimensions of brand awareness in tourism spot marketing [140].

Brand image is the critical driver of brand equity, which refers to consumers’ general perception and feeling about a brand and influences consumer behavior. Marketers strive to influence consumers’ perception and attitude toward a brand, establish the brand image in consumers’ minds, and stimulate consumers’ actual purchasing behavior, increasing sales, maximizing the market share, and developing brand equity. Brand image is essential in building brand equity and, as such, has been studied extensively since the 20th century. In the increasingly competitive world marketplace, companies require deeper insights into consumer behavior and need to educate consumers about the brand to develop effective marketing strategies. According to Keller [119,121], a positive brand image is established through marketing campaigns connecting the brand’s unique and strong brand association with consumers’ memories. In this regard, brand knowledge should be built and understood before consumers respond positively to the branding campaign. If consumers know a brand, the company could spend less on brand extension while achieving higher sales [141]. Visitors’ motives before visiting scenic spots and their feelings after a visit will be communicated via word-of-mouth. This will gradually form a socially universal evaluation of the destination brand [142] and shape the concept of brand identity, which covers the dual nature of attracting consumers’ (rational appeals) and hearts (emotional appeals) [143].

Religious tourism marketing requires a spiritual asset to better suit travelers’ needs, like a pilgrimage or moral satisfaction, at a reasonable cost and convenience. Sightseeing participants also require information about the merits of traveling, observing, and experiencing a religious heritage or celebration. Haq argues that in contrast to the traditional marketing mix, relationship marketing can be viable for religious tourism, as it has been preferred for tourism marketing for some time [144].

Visitors with a common faith could increase the visit motivation; however, the brand’s reputation and trust require significant resources and time to ferment before growing steadily. Among the many highly homogenized religious attractions, this study investigates if tourists have a strong desire to visit or revisit the “100 Religious Attractions” in Taiwan, whether they can become deeply ingrained in the minds of tourists, and become a reputable travel brand. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4.

Tourists have a strong desire to visit/revisit other similar religious places or events listed in the “100 Religious Attractions”. They also believe that the “100 Religious Attractions” is a strong tourism brand.

2.6. Visitors’ Self-Claimed Identity in Religious Tourism

Some scholars believe that the culture transforms specific natural and geographical landscapes into sacred landscapes under the general trend of tourism development. In this change process, visitors’ behaviors, habits, and mindsets, driven by regional differences, are also changed [145,146,147]. Kaszowski [145] defined a pilgrim at the theoretical level as an individual who:

- Can accurately identify a real pilgrimage.

- Knows which steps to perform in the pilgrimage.

- Understands at what time (major festival) to participate in the pilgrimage.

At the practical level, a pilgrim is defined as an individual who: (1) has a comprehensive plan for the overall pilgrimage; (2) through the pilgrimage, raises one’s spiritual level or develops beliefs. In reality, the original motivation has no connection with religion; tourists may also pilgrimage. Similar to traditional tourism, the motivation can be pure entertainment. Therefore, the line between tourism and pilgrimage is blurred [16,148]. Huang and Pearce found that tourists’ Buddhist beliefs are related to their classification and evaluation of Buddhist Mountain tours [82]. Nonbelievers pay more attention to the natural characteristics of the local area and are perhaps less interested in Buddhist culture; they visit primarily for sightseeing or entertainment. Neutral visitors’ opinions include various responses, but most regard the Buddhist Mountain tours as sacred cultural sites. Finally, an unexpected result is that the more loyal believers think that the Buddhist Mountain tours are cultural or beautiful, but their interest in the sacredness is not as high as anticipated. In addition, some faithful believers said that the Buddhist venues are too commercial.

Religion and tourism have been closely related for a long time [149]. Therefore, pilgrimage routes can drive sustainable development, especially in rural and marginal areas, where “slow” tourism has increased [150]. In the form of identity, the internal adjustment is mainly based on the general spiritual cognition and, in particular, on comprehending spiritual tourism. Identity explains how tourists participate in spiritual tourism and why this experience is a kind of coercion, obligation, and guilt; how the space of fear participates in this experience catalyzes happiness and motivation. The recognition process enables people to show a constant sense of happiness, desire, and interest in activities [151,152]. Due to the high similarity between pilgrimage and tourism behavior, this study allows the interviewees to self-identify as pilgrims or general tourists. This is a moderator to analyze if and how the subjects’ self-identity affects their willingness to visit/revisit.

Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 5.

Visitors from religious believers versus non-believer travelers moderate the relationship between willingness to visit/revisit and “100 Religious Attractions” brand trust.

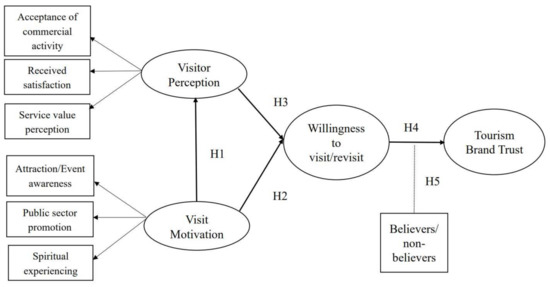

2.7. Proposed Model

This model’s design portrays visitors’ attitudes toward “100 Religious Attractions” as a tourism brand. The first route establishes the relationship between the three elements of attraction/event awareness, public sector promotion, and spiritual experiences, and traveler’s motivation as the primary relationship. It determines how “to visit” motivation forms in an individual’s mind and how it may lead to a desire to visit the “100 Religious Attractions.” Therefore, this research focuses on tourists’ motivation in religious tourism and their motivations, activities, ritual performances, and experiences [6,153].

In addition to understanding the major factors (acceptance of commercial activity, received satisfaction, and service value perception) influencing religious attraction visitors’ perceptions [6,153,154], it becomes necessary to verify which aspects shape and influence potential visitors’ motivation and experienced visitor’s perceptions. It is also essential to determine whether such perception can be successfully converted into revisiting willingness [155]. Therefore, the second and third routes construct the relationship between traveler motivation and willingness to visit and experienced travelers’ perceptions and willingness to revisit. Furthermore, this research examines whether such a desire to visit/revisit is strong enough to establish the “100 Religious Attractions” as a solid tourism brand, encouraging visitors to visit/revisit and actively recommend it to others [82]. Therefore, the fourth route observes the relationship between willingness to visit/revisit and tourism brand trust.

The traveler’s self-proclaimed religious identity (believer or non-believer) is used as a moderating variable to observe whether their satisfaction will affect the “100 Religious Attractions” becoming a solid tourism brand. The testing of these relationships is necessary for the evaluation of comparative hypotheses.

In summary, the first part of this section sought to verify how a traveler’s sense of motivation and perception forms, as per the model in Figure 1. Based on the results, the second part observes the relationship among visit motivation, perception, and willingness to visit/revisit. We tested the hypotheses, adapted the questionnaire for travelers, and measured their opinions regarding willingness to visit/revisit and tourism brand trust under their self-proclaimed religious belief identity.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Methodology

In July 2021, researchers conducted in-depth interviews with 30 tourists who had visited more than 30 attraction sites on the “100 Religious Attractions” list. The interviews were analyzed to identify the four aspects of travel motivation, experience perception, revisit intention, and overall attitude toward the attractions visited. The resultant information was incorporated into the survey questionnaire for use in the large-scale study.

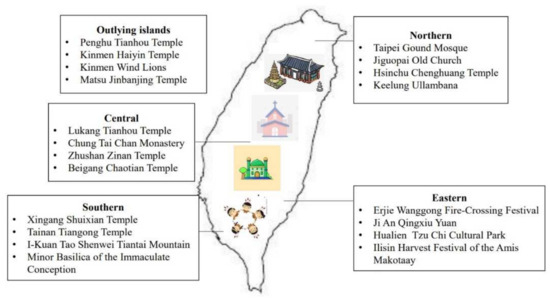

The questionnaire included three sections. The first part aimed to classify visitor motivation (including attraction/event awareness, public sector promotional efforts, and spiritual experiencing) for potential and experienced tourists and visitor perceptions, covering commercial activity acceptance, received satisfaction, and service value perception. The second process is related to the willingness to visit or revisit and the question of whether such willingness can be successfully transformed into a trustworthy travel brand. Finally, the third section questioned socio-demographic information regarding gender, personal beliefs, age, marriage, education background, occupation, number of listed-attraction visits, and personal monthly income. The data were collected from twenty representative attractions and folklore belief ceremonies listed in “100 Religious Attractions” (four each in five geographic parts of Taiwan, for 20 total attractions; Figure 2). The data included when tourists visited the spot for every covered religious belief, e.g., Aboriginal, Buddhism, Catholic, Christianity, Folklore, and Muslim. Convenience sampling was used, and data were gathered from August 23 to September 22, 2021, one month before the Chinese Mid-Autumn Festival. A total of 500 questionnaires were issued to religious visitors. After excluding missing and invalid data, 385 valid responses (approximately 77.0%) were applied in further analysis. The sample size was in line with the literature for structural equation models with similar complexity [156,157,158,159].

Figure 2.

The surveyed attractions of this study.

This study conducted in-person interviews. We asked respondents to indicate the attraction or events listed in “100 Religious Attractions” that they had most recently been interested in or visited. We used a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = extremely disagree to 5 = strongly agree) to acquire responses regarding “to see” motivation, sightseeing spot perception, revisit intention, and brand trust items. The wording was slightly modified to reflect the context of this study. The survey instrument was compiled using measurement items generated from the extant literature. The use of existing scales ensured the reliability and validity of the survey instrument.

The respondents included more female tourists; 173 (44.9%) were male, and 212 (55.1%) were female. Most interviewees (81.3%) had religious beliefs, and 18.7% had no specific faith. Most respondents were 36–65 years old (57.8%), and 21.3% were more than 65 years old. A large proportion of the respondents (66.7%) were married, while 33.3% were single. Most participants had high school (37.9%) and tertiary level (39.8%) education; only 11.5% had master’s or above. In terms of occupation, enterprise employees (31.9%) and self-employed (25.9%) represented a large proportion of respondents, while retirees made up 17.6%. Visit times were more balanced, and 20.6% of interviewees had never visited the “100 Religious Attractions”, 19.8% said they visited 50–69 attractions, and 26.3% had been to more than 70 attractions. Regarding the willingness to spend during the journey, nearly half of the interviewees (49.1%) spent NTD 200–499 (approximately USD 3.62–18.0). Lastly, the respondents were asked to select from three options to determine their intent to purchase. The most popular items were worship supplies (e.g., prayer stick, joss paper, worship offerings) (67.0%), followed by amulets sold by the attraction, at 59.6%. Only 12.2% of interviewees indicated no intent to purchase (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic information (N = 385).

To analyze the data and test our hypotheses, we used AMOS 23.0 to apply a multivariate analysis through structural equation modeling. We opted for this technique because of its robustness in evaluating concomitant associations among endogenous and exogenous variables. This study obtained the validity of the structural model using confirmatory factor analysis, verifying both the convergent validity and the discriminant validity. We subsequently tested our hypotheses.

In addition to testing the hypotheses, any differences in the variables’ path coefficients were ascertained, following Hult et al. [160]. Hair et al. mentioned that this was necessary because it is impossible to affirm that parallel path coefficients in the same model are distinct based only on their significance and indicators [161]. We chose this method because it is a structural equation modeling technique that can test models with unobserved variables or constructs [162] and solve various forms of construct operability [163].

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

To evaluate the model constructs and validate the appropriateness of the collected data, we carried out a confirmatory factor analysis to ascertain the convergent and discriminant validity. We calculated the factorial weightings for the confirmatory factor matrix study for the research assertions about their constructs.

The convergent validity refers to the extent to which the construct indicators measure the construct, thus indicating how these variables correlate with each other [160]. Discriminant validity refers to the capacity of a construct to be genuinely distinctive [160]. Using the factorial matrix, we observe how the factorial weightings identify this study’s various factors. No cross weightings were reported among the constructs, confirming the discriminant validity. As Table 3 (the factor loading results) shows, there is no obvious variable across the model’s two latent variable factors. The originally constructed explicit variables all fall within the expected latent variable factor framework, and the factor loadings are all greater than 0.5, indicating that the model has good discriminative validity [164]. Furthermore, Table 4 reveals that the cumulative variance explanation rate after rotation was 78.917%, meaning that the information embedded in the research item can be extracted effectively [165,166].

Table 3.

Factor loadings *.

Table 4.

Total variance explained *.

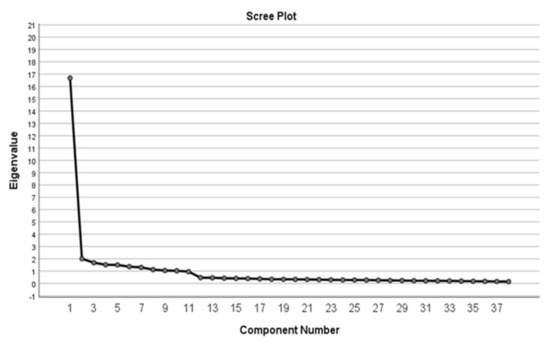

Table 5 shows that the KMO is 0.956, which is greater than 0.6 and passes the Bartlett sphericity test (p < 0.05), indicating that the data can be used for factor analysis research. From the screen plot of factor analysis in Figure 3, the graphical judgment method proposed by Cattell [167] clearly shows that the eigenvalue is greater than 1 and the corresponding component number is 11. Thus, the 10 main factors selected in this study are reasonable and meet the statistical analysis needs. We calculated the average variance extracted (AVE) validity before concluding that all the latent variables attained the set criteria. Composite reliability (CR), which also represents an indicator of convergent validity, ensures the evaluation of the magnitude by which the items in an instrument correlate with each other. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed in the present study for ten factors and 37 analysis items. The AVE values corresponding to a total of 10 factors are all greater than 0.5, and the CR values are all greater than 0.7, meaning that the data in this analysis have good convergence validity [160,168].

Table 5.

Correlations and quality criteria *.

Figure 3.

Scree plot.

Finally, to fulfill the discriminant validity, we compared the square roots of the AVE for each construct with the results returned by their respective correlations, as proposed by Fornell and Larcker [169]. The AVE square root index for each latent variable was higher than that of the other construct, indicating their respective mutual independence. Table 5 illustrates the correlations and quality criteria.

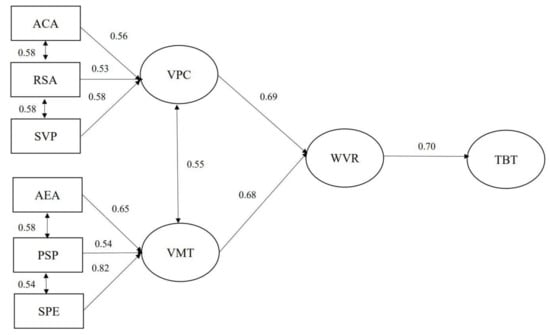

4.2. Structural Model Assessment Results

A structural model may represent the dependent relations between constructs [159,170]. Therefore, this study presents the structural model and path coefficients in the combined layout, including several correlates of factors reported in previous research: acceptance of commercial activity, received satisfaction, and service value perception linked with visit motivation and willingness to visit or revisit; attraction/event awareness, public sector promotion, and spiritual experience in taking part of willingness to visit or revisit. Next, whether the path between the willingness to visit or revisit establishes the visitor’s tourism brand trust is examined. All of these factors were simultaneously analyzed to determine the likelihood of a new religious-based tourism brand trust. Figure 4 reveals the theoretical SEM model with arrows and coefficients, no dotted lines between each factor, and the path coefficients are all positive. That is to say, the relationship of each factor is well-established. Once the initial determination is achieved, the research hypotheses can be tested.

Figure 4.

Structural model. ACA acceptance of commercial activity, RSA received satisfaction, SVP service value perception, VPC visitors’ perception, AEA attraction/event awareness, PSP public sector promotion, SPE spiritual experiencing, VMT visit motivation, WVR willingness to visit/revisit, TBT tourism brand trust.

4.2.1. Hypotheses Testing

This phase analyzes the extent to which visit motivation and perception affect tourists’ willingness to visit and revisit the “100 Religious Attractions”. Results for the research hypotheses are summarized in Table 6. Consistent with the SEM result, the study model indicates a good fit for the data: x2 = 820.949, df = 604, x2/df = 1.359 (Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.902; Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.980; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.016). In the study hypotheses, the estimation of the standardized coefficients indicates that the path between each dimension was positive and significant. In other words, visit motivation (including attraction/event awareness, public sector promotion, and spiritual experiencing) affects tourists’ perceptions (including acceptance of commercial activity, received satisfaction, and service value perception). Simultaneously, the visitor perception factors affect their willingness to visit/revisit. Similarly, the willingness to visit/revisit has a certain impact on tourists’ trust in the “100 Religious Attractions” tourism brand. Therefore, H1 to H4 are supported (Table 6).

Table 6.

Path coefficients and hypothesis results *.

Tourists’ trust in destination brands arises primarily from subjective feelings [171,172], and religious-themed tourist destinations are no exception [173,174]. Important branding tourist destination factors include the source accessibility of the scenic spot’s information, the spiritual experience, and the unique commercial activity [175]; all of these factors indicate that visit motivation and perception depend on several uncontrollable factors [49, 176]. As encapsulated in Hypotheses 1–3, and in keeping with other related studies, visitor motivation and perception positively influence tourists’ willingness to visit/revisit. Additionally, Hypothesis 4′s result echoed the conclusions of Cheng, Wei, and Zhang [142] and Alvarado-Karste and Guzmán [143]; namely, the willingness to visit/revisit shapes the awareness and identity of the destination brand through word-of-mouth, and perceived satisfaction mediated the effects of the trust in the brand.

The present findings broaden the knowledge regarding the formation of trust by showing the influence of visit motivation and visitor perceptions of a newly developing tourist destination brand. The conclusion is that the subjective attitudes of tourists influence their willingness to visit or revisit and further enhance the destination brand trust. The development of a brand requires accumulated goodwill, especially for the tourism industry that provides software and hardware services. This study reflects the increasing importance of tourists’ motivation to visit and subjective perceptions of receiving services in building trust in tourism brands, strengthening the theoretical connection between constructs. Therefore, tourism operators must determine and respect visitors’ views on service delivery and related experiences. The tourism sector must realize that effectively strengthening the overall feelings of tourists regarding attractions can not only increase their willingness to visit, but also their confidence in the entire tourism brand. Meanwhile, such enhancement is also helpful for the establishment and long-term development of sustainable tourism brands.

4.2.2. Moderation Effect Testing

To test Hypothesis 5, we examined the moderating effect of a tourist’s personal religious belief on the relationship between their willingness to visit/revisit and attitude toward religious-themed destination brand trust, following Iliev [148] and Huang and Pearce [82]. The moderating effect is divided into three models: Model 1 includes independent variables (willingness to visit/revisit); Model 2 adds the moderating variable (religious identity) based on Model 1; and Model 3 adds an interaction term (religious identity and tourist brand trust) based on Model 2.

Model 1′s purpose is to study the influence of the independent variable (willingness to visit/revisit) on the dependent variable (tourist brand trust) without considering the interference of a tourist’s religious identity. Table 7 shows that satisfaction is significant (t = 14.505, p = 0.000 < 0.05). This means that tourists’ willingness to visit/revisit will significantly influence tourist brand trust.

Table 7.

Result of moderating test.

The moderation effect can be checked in two ways. The first is to check the significance of the change in the F value from Model 2 to Model 3. The second is to check the significance of the interaction term in Model 3. This study used the second method to analyze the moderation effect to verify whether visitors’ religious identity strengthens willingness to visit/revisit the destination brand trust.

Table 7 shows that the interaction term between visitors’ willingness to visit or revisit and their religious identity is not significant (t = −1.297, p = 0.195 > 0.05). In other words, Hypothesis 5 is not supported; although a visitor’s willingness to visit or revisit influences their destination brand trust in terms of Model 1, for different levels of the moderating variable (tourist’s religious identity), the impact range remains the same.

5. Discussion

This study has several important theoretical and managerial insights for creating a sustainable tourism brand, visiting religious sites, and willingness to consume. Consistent with Wang et al. [176], Gupta and Basak [177], and Bond et al. [178], there is no evident difference in influence between a believer and non-believer visitor. Although the motives for visiting may differ, believers and nonbelievers have surprisingly consistent perceptions of whether the willingness to stay can be transformed into brand trust. In other words, the degree of trust that tourists have in tourism brands must return to the essence of tourism reception services, from the optimization of hardware and software facilities, the etiquette of reception staff, the sightseeing location of tourist attractions, promotion, publicity, and the religious atmosphere. The spiritual experience is all spontaneously felt deep in the visitors’ hearts.

According to the actual observation and the mean score of each variable item in the Appendix A and Appendix B, we find some interesting results from this study. Regarding influencing visiting motivation, the spiritual experience among the “100 Religious Attractions” is the most significant factor. Due to the drastic changes in internal and external social and economic environments in recent years, many people’s lives have been affected. As far as Taiwanese society is concerned, the “retirement annuity pension reform” has affected many retirees’ economic situation in recent years. When it is not easy to increase income, they can only reduce their expenses and seek lower satisfaction levels. Coupled with the impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, many working-class people have had unstable incomes, and many people have lost their jobs and faced difficulties. For this reason, “seeking inner peace” has become the primary motivation for tourists to visit the scenic spots among the “100 Religious Attractions”.

Similarly, based on the identity analysis of the interviewees, in terms of gender, there were more female interviewees. This result is the same as the extant literature [2,86,111], which suggests that women are more likely to visit religious sites for worship or spiritual experiences. This phenomenon may be because, compared with men, women are more likely to seek out metaphysical, spiritual needs, such as fortune-telling [179,180]. Some women have more free time to find relatives and friends to pray for family members in the temple, primarily because families depend more on male members for support. We also found more retirement groups, which is also due to the previous motivation. Conversely, wage earners seek smooth careers, and self-employed people hope for business stability; these are general demand motives. Many of the interviewees who filled in “other” occupations were unemployed, dismissed, involved in civil service examinations, professional qualifications, or seeking higher education opportunities. There was also motivation to pray for the deities to bless these individuals, realizing their wishes that “everything is going well”.

Many interviewees said they learned about a specific event because they participated in the Internet voting for Taiwan’s “100 Religious Attractions”. They also used the Internet to support religious sites in their hometowns or familiar sacred sites. This group phenomenon also stimulated the motivation and willingness of the interviewees to visit, which coincides with the findings of Zhou et al. [181]. Tourists hoped their supported attractions would be voted into the “100 Religious Attractions”. Some participants actively shared and promoted the environmental advantages, beautiful scenery, and other “selling points” of their preferred scenic spots to increase the chances of winning, resulting in word-of-mouth communication. In addition, the role of media advertising also reminded the interviewees of the scenic areas, stimulating their motivation to see or visit again.

The travel journals, notes, blogs, and comments that tourists generate online can be called electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) [182,183,184,185]. For tourists, there are many types of eWOM platforms, including blogs (e.g., travel blog) and microblogs (e.g., Weibo, Twitter), social networking sites (e.g., WeChat, Line, Facebook), media-sharing sites (e.g., YouTube, Tik Tok), review sites (e.g., C-trip, TripAdvisor), and voting sites (e.g., Digg) [181,185,186,187,188]. The public sector mainly initiated the “100 Religious Attractions” voting activities. At the same time, a large amount of publicity on social media attracted the active participation of people from all walks of life and also had an excellent effect on eWOM. The attention paid to the scenic spots had no significant impact on the motivation to visit because most of the “100 Religious Attractions” had long histories and specific influences in the region. Although the attraction/event can trigger tourists’ motivation to visit, the effect is not obvious.

Regarding visitors’ perception, most respondents agreed that “service value perception” was the critical influencing factor. The attractions provided adequate basic infrastructures, such as sufficient parking, barrier-free facilities, and safety protection measures, essential points for tourists. The convenience of transportation around sightseeing spots also affected tourists’ perceptions of service value. Moreover, well-arranged sightseeing planning can also make visitors feel that the value of their services is truly reflected.

It is worth mentioning that tourists’ acceptance of commercial activities inside and outside the scenic spots is not as harmful as previous scholars believed it to be. This surprising result can be observed by combining the surveyed “amount willing to buy” and “the item willing to buy.” Only a few respondents were unwilling to buy various products and services inside and outside the scenic area. Most interviewees had a purchase budget of USD 3.62–18. They purchased sacrificial supplies, like incense sticks, joss paper, bouquets in Chinese folk beliefs, or white candles in Catholic churches. In addition, the demand for accommodation was the focus of consumption, which is usually expensive compared with the surrounding goods and services of other scenic spots. In some attractions with inconvenient transportation, the demand and price of accommodation increased significantly. Other purchase items included amulets and mascots. In Taiwan, religious institutions sell small commodities related to spiritual prayers because most religious attractions do not charge entry. In addition to receiving donations, income comes from sesame oil, other religious services (e.g., religious blessing ceremony) [41], and cultural and creative products or other related investments (such as leasing industry, providing accommodation).

Furthermore, most well-known religious attractions are in towns with relatively long histories, providing many renowned gourmet and gift shops or vendors. These can add a deep impression to tourists’ tourism perception, enhancing their willingness to visit/revisit. Still, this positive reaction is based on satisfying some conditions (e.g., fair and reasonable prices, products, and services) that can fully meet the consumers’ needs.

The tourists’ feelings are also primarily related to the received service satisfaction. Their perceived value is the crucial antecedent of patronage, re-patronage intention, satisfaction, and loyalty [189]. Perceptions significantly impact customers repurchase intentions [190,191,192,193]. The survey results also showed positive feedback from the respondents. For example, positive interactions with service providers made the whole trip worthwhile. In the research process, after excluding factors that might be due to the location of the nearby scenic spot, numerous interviewees said that they visited certain scenic areas several times a year, primarily because of the scenic locations, a local gourmet, or some specialty shops.

This empirical study verifies the willingness of tourists to visit/revisit is closely related to the pre-visit motivation and the perception after the trip. In addition, the research results verified that such a willingness could be smoothly transformed into trust in the “100 Religious Attractions” tourism brand. The feedback from the interviewees indicated that the “100 Religious Attractions” had a certain degree of brand trust. Nevertheless, establishing a tourism brand’s image and assets takes time to accumulate, and it simultaneously requires cooperation between many aspects and sectors to create a sustainable tourism brand. Rainisto [51] and Cohen’s [52] categorization may help the tourism sector develop strategies for the effective marketing of religious tourism by explaining each type of traveler and providing guidelines for attracting them.

For example, the “Temple Stay in Taiwan” official website under the “100 Religious Attractions” offers numerous vacation packages. A viewer can search through “experiencing periods”, “experiential patterns”, and “religious attributes” to seek their favorite trip [42]. Whether a devout believer or an ordinary traveler, the website provides the appropriate schedule and program details. Notably, this study reveals that package tours commonly organize religious tourists. Their travel mates mainly influence an individual’s desire to attend a religious-themed journey. Relationship marketing has echoed Haq’s arguments [144]; therefore, all stakeholders in the tourism industry should eliminate selfish departmentalism, completely cooperate in planning, and launch appropriate package programs that meet the needs of tourists. Making tourists fully experience the convenience and cultural significance during the journey is even more important in establishing a solid tourism brand.

All stakeholders must coordinate the tourism sector to satisfy the diverse needs of tourists. Therefore, the purpose of branding the tourism destination should be to establish relationships that create opportunities to further business interests and contribute positively to the destination’s competitiveness. After all, the success of individual tourism businesses will ultimately rely on their destination’s competitiveness [29,129,134]. In this way, it is possible to create a sustainable tourism brand that can be trusted by tourists and comprehensively considers environmental protection, social recognition, and corporate development.

6. Conclusions

The present study contrasts with the extant literature and found that when tourists travel to religious sites, they are not subjectively repelled by nearby commercial activities; however, they must feel valuable and satisfied during the consumption process, and the prices should be reasonable. The most critical factor influencing tourists’ motivation to visit is the spiritual experience, and blessings play a significant role. As such, advertising campaigns, funded by the public sector, launched on social media can also stimulate tourists to visit. Furthermore, visitors’ perceptions of the commercial activities, received service value, and satisfaction during visits to religious attractions profoundly impact their travel experience. In addition to enhancing visitors’ willingness to visit/revisit, such factors also strengthened their trust in travel brands.

This empirical study provides management insights that developing a sustainable tourism brand requires the cooperation of various stakeholders in the tourism sector. In addition to launching new tourism activities promptly and stimulating motivation to visit, it is necessary to pay attention to tourists’ diverse needs and create the experience value of the passengers to attract more tourists and further develop an irreplaceable tourism brand.

This study has several limitations. First, it is limited to tourists’ visit motivation and experiencing perception in a newly created tourism brand within a specific region; as such, the findings may not fully reflect the numerous problems while developing tourism brands. Second, this study only describes whether the research path between visit motivation, visitor perception, and tourists’ willingness to visit/revisit produce trust in the tourism brand. Still, the motivation and experience of religious site visitors are full of dynamics [174]. For instance, many interviewees decided to visit a particularly scenic spot, mainly based on their past experiences. Simply speaking, they visited with a feeling of nostalgia. Future research can examine the relationships between the sense of homesickness and willingness to visit/revisit tourism brand development issues.

Future research can explore the relationship between religious site visits in promoting the sustainability of tourism brand development and the cultural and spiritual lives of tourists, which can enrich the knowledge in this field. Moreover, the sample of selected demographic variables. More than 99% of the respondents were in Taiwan. They have high cultural homogeneity, so it does not reflect the apparent differences in willingness to revisit and a sustainable tourism brand development. Future research should focus on samples in regions with substantial social and cultural heterogeneity. Various cultures have a different impact on tourists’ motivation, service perception, and assessment. Therefore, a cross-country sample should compare the overall willingness to visit/revisit, consumption habits, and brand identification among religious scenic spot guests of different cultures.

Funding

This work was funded by Talent Support Project of Guangdong University of Petrochemical Technology (Ref. No. 702-519197).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used in this study is public.

Acknowledgments

The author appreciate the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions that significantly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Measurement Instrument

Acceptance of Commercial Activity (ACA) [88,89,90]

- ACA1. Commercial atmosphere is not too strong

- ACA2. Shopping store and vendors fit my needs

- ACA3. Shopping store and vendors has good reputation

- ACA4. Sale items is fair and reasonable price

Received Satisfaction (RSA) [66]

- RSA1. Service providers cared about my needs

- RSA2. I feel the enthusiasm of the service staff.

- RSA3. Overall, my vacation trip at here is a good buy

Service Value Perception (SVP) [102]

- SVP1. This attraction/event have completed and appropriate infrastructure (e.g., parking space, accessible facility, safety measures)

- SVP2. The sightseeing line is properly arranged

- SVP3. Transportation is very convenience

- SVP4. This attraction/event facilitate formal and informal educational opportunities

Attraction/Event Awareness (AEA) [58]

- AEA1. This attraction/event has strong significant representative of this religious belief.

- AEA2. I knew this attraction/event in long time ago.

- AEA3. My intention to visit this attraction/event since a long time ago.

Public Sector Promotion (PSP) [66]

- PSP1. The voting activity of “Taiwan 100 Religious Attractions” did cause a boom in the social network services.

- PSP2. I have participated the voting activity, and showed my support to my favored attraction/events.

- PSP3. The advertisement of “Taiwan 100 Religious Attractions” brought memories to my mind.

- PSP4. I found myself thinking of images of “Taiwan 100 Religious Attractions” when I read the advertisement.

Spiritual Experiencing (SPE) [77]

- SPE1. When I come to visit or worship here, I feel inner peace in my mind.

- SPE2. When I come to visit or worship here, I feel that everything is going well.

- SPE3. When I come to visit or worship here, I feel that bringing me closer to the practice of doctrine.

- SPE4. When I come to visit or worship here, I feel the Deity I trusted is listening what I say.

Visit Motivation (VMT) [51,52]

- VMT1. Seeing and learning a new attraction and experiences.

- VMT2. Worth to accompany family/friends.

- VMT3. Fulfill my leisure and spiritual life.

- VMT4. The advertising method is very attractive to me.

Visitor Perception (VPC) [84]

- VPC1. This attraction makes me full of relaxation.

- VPC2. This attraction meets my expectation.

- VPC3. This attraction improved my feeling experience.

- VPC4. I am happy to spend more here.

Willingness to Visit/Revisit (WVR) [112,113,114,115,116]

- WVR1. The probability that I will visit “Taiwan 100 Religious Attractions” list spot again is high.

- WVR2. I consider myself a loyal patron of the list of “Taiwan 100 Religious Attractions”.

- WVR3. I would like to stay more days in destination of “Taiwan 100 Religious Attractions”.

- WVR4. I would like to recommend others to visit “Taiwan 100 Religious Attractions”.

Tourism Brand Trust (TBT) [144]

- TBT1. The destinations of “Taiwan 100 Religious Attractions” are congruent to its behavior.

- TBT2. The destinations of “Taiwan 100 Religious Attractions” are very competent regarding of their promote items.

- TBT3. The destinations of “Taiwan 100 Religious Attractions” performs consistently.

- TBT4. I feel comfortable depending on the destinations of “Taiwan 100 Religious Attractions”.

Appendix B

Table B1.

Mean (M), std., deviation, kurtosis, and skewness values.

Table B1.

Mean (M), std., deviation, kurtosis, and skewness values.

| Items | Mean | Std. Deviation | Excess Kurtosis | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACA1 | 3.40 | 1.137 | −1.023 | −0.132 |

| ACA2 | 3.28 | 1.141 | −0.944 | −0.069 |

| ACA3 | 3.31 | 1.171 | −0.986 | −0.166 |

| ACA4 | 3.25 | 1.099 | −0.769 | −0.028 |

| RSA1 | 3.30 | 1.194 | −0.943 | −0.124 |

| RSA2 | 3.27 | 1.151 | −0.792 | −0.218 |

| RSA3 | 3.24 | 1.150 | −0.865 | −0.131 |

| SVP1 | 3.30 | 1.123 | −0.888 | −0.137 |

| SVP2 | 3.25 | 1.179 | −0.988 | −0.101 |

| SVP3 | 3.19 | 1.100 | −0.660 | −0.026 |

| SVP4 | 3.35 | 1.158 | −0.851 | −0.263 |

| AEA1 | 3.40 | 1.090 | −0.579 | −0.409 |

| AEA2 | 3.39 | 1.124 | −0.704 | −0.314 |

| AEA3 | 3.29 | 1.116 | −0.821 | −0.119 |

| PSP1 | 3.24 | 1.098 | −0.821 | −0.081 |

| PSP2 | 3.25 | 1.133 | −0.773 | −0.124 |

| PSP3 | 3.25 | 1.149 | −0.818 | −0.038 |

| PSP4 | 3.28 | 1.125 | −0.880 | −0.133 |

| SPE1 | 3.25 | 1.031 | −0.673 | −0.041 |

| SPE2 | 3.21 | 1.124 | −0.682 | −0.057 |

| SPE3 | 3.21 | 1.112 | −0.727 | −0.143 |

| SPE4 | 3.25 | 1.099 | −0.674 | −0.060 |

| VMT1 | 3.26 | 1.134 | −0.737 | −0.130 |

| VMT2 | 3.24 | 1.106 | −0.750 | −0.083 |

| VMT3 | 3.20 | 1.115 | −0.757 | −0.084 |

| VMT4 | 3.26 | 1.106 | −0.683 | −0.151 |

| VPC1 | 3.19 | 1.177 | −0.902 | −0.075 |

| VPC2 | 3.17 | 1.149 | −0.872 | −0.070 |

| VPC3 | 3.12 | 1.143 | −0.797 | −0.041 |

| VPC4 | 3.22 | 1.159 | −0.753 | −0.181 |

| WVR1 | 3.30 | 1.100 | −0.783 | −0.153 |

| WVR2 | 3.25 | 1.091 | −0.733 | −0.096 |

| WVR3 | 3.28 | 1.078 | −0.719 | −0.118 |

| WVR4 | 3.17 | 1.122 | −0.786 | −0.025 |

| TBT1 | 3.30 | 1.104 | −0.825 | −0.117 |

| TBT2 | 3.32 | 1.155 | −0.939 | −0.122 |

| TBT3 | 3.19 | 1.225 | −0.878 | −0.197 |

| TBT4 | 3.25 | 1.243 | −1.047 | −0.231 |

References

- Hu, Y. An Exploration of the Relationships between Festival Expenditures, Motivations and Food Involvement among Food Festival visitors. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Canada, December 2010. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10012/5650 (accessed on 2 January 2022).