Food Wastage Attitudes among the United Arab Emirates Population: The Role of Social Media

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

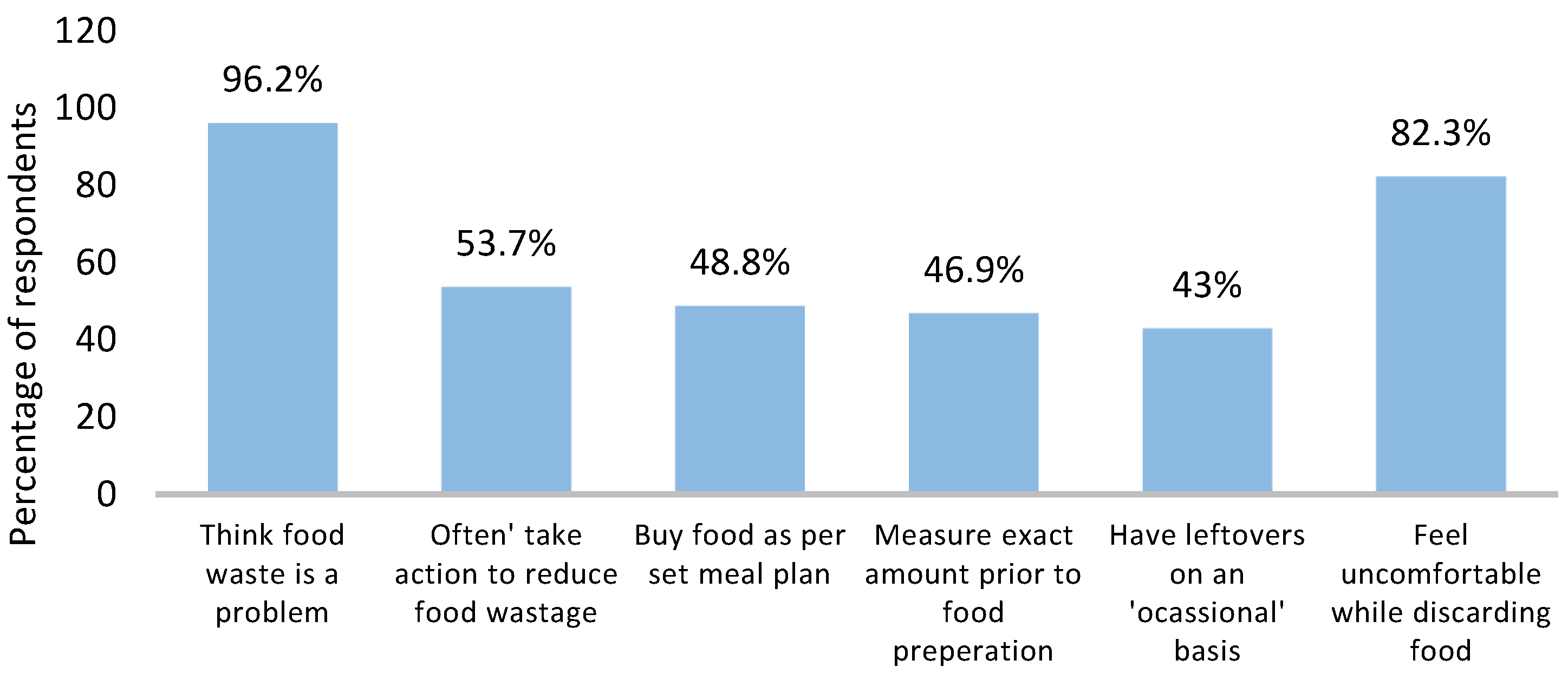

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GuGustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste Save; Food Congress: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges. Available online: https://books.google.ae/books?id=SRFfDwAAQBAJ (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Scialabba, N.; Müller, A.; Schader, C.; Schmidt, U.; Schwegler, P.; Fujiwara, D.; Ghoreishi, Y. Food Wastage Footprint: Full-Cost Accounting (Final Report). Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3991e/i3991e.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- EAD Waste Management. Available online: https://www.ead.gov.ae/storage/Post/files/0ddcde55f035555af0b341b5084ecbc4.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- World Food Program 5 Facts about Food Waste and Hunger|World Food Programme. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/stories/5-facts-about-food-waste-and-hunger (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Teigiserova, D.A.; Hamelin, L.; Thomsen, M. Towards transparent valorization of food surplus, waste and loss: Clarifying definitions, food waste hierarchy, and role in the circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 136033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.G.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Timmermans, A.J.M.; Ambuko, J.; Belik, W.; Huang, J. Food Losses and Waste in the Context of Sustainable Food Systems. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3901e/i3901e.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Kumar, K.; Yadav, A.N.; Kumar, V.; Vyas, P.; Dhaliwal, H.S. Food waste: A potential bioresource for extraction of nutraceuticals and bioactive compounds. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2017, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Domi, H.; Al-Rawajfeh, H.; Aboyousif, F.; Yaghi, S.; Mashal, R.; Fakhoury, J. Determining and addressing food plate waste in a group of students at the University of Jordan. Pak. J. Nutr. 2011, 10, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodhuyzen, D.M.A.; Luning, P.A.; Fogliano, V.; Steenbekkers, L.P.A. Putting together the puzzle of consumer food waste: Towards an integral perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger the Environmental Impact of Food Waste. Available online: https://moveforhunger.org/the-environmental-impact-of-food-waste (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Lins, M.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Strasburg, V.J.; Nakano, E.Y.; Botelho, R.B.A.; Raposo, A.; Ginani, V.C. Eco-Inefficiency Formula: A Method to Verify the Cost of the Economic, Environmental, and Social Impact of Waste in Food Services. Foods 2021, 10, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, M.; Puppin Zandonadi, R.; Raposo, A.; Ginani, V.C. Food Waste on Foodservice: An Overview through the Perspective of Sustainable Dimensions. Foods 2021, 10, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jribi, S.; Ben Ismail, H.; Doggui, D.; Debbabi, H. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3939–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macková, M.; Hazuchová, N.; Stávková, J. Czech consumers’ attitudes to food waste. Agric. Econ. 2019, 65, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marangon, F.; Tempesta, T.; Troiano, S.; Vecchiato, D. Food waste, consumer attitudes and behaviour. A study in the North-Eastern part of Italy. Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2014, 69, 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- Berjan, S.; Mrdalj, V.; El Bilali, H.; Velimirovic, A.; Blagojevic, Z.; Bottalico, F.; Debs, P.; Capone, R. Household food waste in Montenegro. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2019, 31, 274–287. [Google Scholar]

- Preka, R.; Berjan, S.; Capone, R.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, M.S.; Debs, P.; Bottalico, F.; Mrdalj, V. Household food wastage in Albania: Causes, extent and implications. Future Food J. Food Agric. Soc. 2020, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, A.; Priyadarshini, A. A study of consumer behaviour towards food-waste in Ireland: Attitudes, quantities and global warming potentials. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 284, 112046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIA. The World Factbook. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/united-arab-emirates (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Winnow Ways to Manage Large Scale Food Waste. Available online: https://info.winnowsolutions.com/food-waste-management (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Food Bank, U. The UAE Food Bank Initiative. Available online: https://www.dm.gov.ae/foodbank/ (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Young, W.; Russell, S.V.; Robinson, C.A.; Barkemeyer, R. Can social media be a tool for reducing consumers’ food waste? A behaviour change experiment by a UK retailer. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 117, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farr-Wharton, G.; Foth, M.; Choi, J.H. Identifying factors that promote consumer behaviours causing expired domestic food waste. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bank, W. Literacy Rate-Adult Total-United Arab Emirates. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS?locations=AE (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Bogevska, Z.; Berjan, S.; Capone, R.; Debs, P.; El Bilali, H.; Bottalico, F.; Davitkovska, M. Household food wastage in North Macedonia. Agric. For. Poljopr. I Sumar. 2020, 66, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, H.; Capone, R.; Karanlik, A.; Bottalico, F.; Debs, P.; El Bilali, H. Food wastage in Turkey: An exploratory survey on household food waste. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 4, 483–489. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D.R.; Schindler, P.S.; Sun, J. Business Research Methods; Mcgraw-hill New York: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric theory—25 years ago and now. Educ. Res. 1975, 4, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kadam, P.; Bhalerao, S. Sample size calculation. Int. J. Ayurveda Res. 2010, 1, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Grandhi, B.; Appaiah Singh, J. What a waste! A study of food wastage behavior in Singapore. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2016, 22, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, O.J.; Møller, H. Food wastage in Norway 2013. Status Trends 2009, 13, 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters-A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porpino, G.; Parente, J.; Wansink, B. Food waste paradox: Antecedents of food disposal in low income households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charbel, L.; Capone, R.; Grizi, L.; Debs, P.; Khalife, D.; El Bilali, H.; Bottalico, F. Preliminary insights on household food wastage in Lebanon. J. Food Secur. 2016, 4, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, B.A.-S.; Hartmann, M.; Langen, N. What makes people leave their food? The interaction of personal and situational factors leading to plate leftovers in canteens. Appetite 2017, 116, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.; Kerr, G.; Pearson, D.; Mirosa, M. The attributes of leftovers and higher-order personal values. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1965–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A.; Hagen, L. Out of proportion? The role of leftovers in eating-related affect and behavior. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 81, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizeau, K.; von Massow, M.; Martin, R. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Miloradovic, Z.; Djekic, S.; Tomasevic, I. Household food waste in Serbia–Attitudes, quantities and global warming potential. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Spiker, M.L.; Truant, P.L. Wasted food: US consumers’ reported awareness, attitudes, and behaviors. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marais, M.L.; Smit, Y.; Koen, N.; Lötze, E. Are the attitudes and practices of foodservice managers, catering personnel and students contributing to excessive food wastage at Stellenbosch University? S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 30, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F.; Otterbring, T.; Löfgren, M.; Gustafsson, A. Reasons for household food waste with special attention to packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stefan, V.; van Herpen, E.; Tudoran, A.A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: The importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Jie, F. To waste or not to waste: Exploring motivational factors of Generation Z hospitality employees towards food wastage in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivupuro, H.; Hartikainen, H.; Silvennoinen, K.; Katajajuuri, J.; Heikintalo, N.; Reinikainen, A.; Jalkanen, L. Influence of socio-demographical, behavioural and attitudinal factors on the amount of avoidable food waste generated in Finnish households. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limon, M.R.; Villarino, C.B.J. Knowledge, attitudes and practices on household food waste: Bases for formulation of a recycling system. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2020, 6, 323–340. [Google Scholar]

- Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K.; Chroni, C. Attitudes and behaviour of Greek households regarding food waste prevention. Waste Manag. Res. 2014, 32, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, T.E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, A.D. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviours. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzymińska, M.; Jakubowska, D.; Staniewska, K. Consumer attitude and behaviour towards food waste. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2016, 39, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mganga, P.; Syafrudin, S.; Amirudin, A. A Survey of Students’ Awareness on Food Waste Problems and Their Behaviour towards Food Wastage: A Case Study of Diponegoro University (UNDIP), Indonesia; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2021; Volume 317, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, M.; Srivastava, S.K. Examining the relevance of emotions for regulation of food wastage behaviour: A research agenda. Soc. Bus. 2020, 10, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazell, J. Identifying the Barriers and Opportunities for Food Waste Prevention in Universities: Using Social Media as a Tool for Behaviour Change; Coventry University: West Midlands, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Melbye, E.L.; Onozaka, Y.; Hansen, H. Throwing it all away: Exploring affluent consumers’ attitudes toward wasting edible food. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, Ö.A.; İLyasov, A. The Food Waste in Five-Star Hotels: A Study on Turkish Guests’ Attitudes. J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 2017, 13, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandaruwani, J.A.R.C.; Gnanapala, W.K.A.C. Food wastage and its impacts on sustainable business operations: A study on Sri Lankan tourist hotels. Procedia Food Sci. 2016, 6, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FAO Food Loss and Food Waste. Available online: http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/flw-data)#:~:text=In (accessed on 14 December 2021).

| Parameter | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <20 | 127 | 24.2% |

| 20–30 | 286 | 54.5% | |

| 30–40 | 61 | 11.6% | |

| 40–60 | 50 | 9.5% | |

| >60 | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Gender | Female | 442 | 84.2% |

| Male | 83 | 15.8% | |

| Nationality | Local | 95 | 18.1% |

| Non-Local | 430 | 81.9% | |

| Family Members | 2–4 | 113 | 21.5% |

| 5–8 | 340 | 64.8% | |

| >8 | 72 | 13.7% | |

| Monthly income (DHS) | <20,000 | 190 | 36.2% |

| 20,000–40,000 | 198 | 37.7% | |

| >40,000 | 107 | 20.4% | |

| Food Preparation | Myself | 111 | 21.1% |

| Mother | 321 | 61.1% | |

| Brother/s | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Sister/s | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Maid | 81 | 15.4% | |

| Other | 10 | 1.9% |

| Frequency of Checking a Social Media Site | Do You Decide on the Quantity of Food You Will Prepare? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, I Don’t | Yes, but I Overestimate | Yes, but I Underestimate | Yes, I Measure the Exact Amount I’ll Use | |

| Hourly | 44 | 116 | 23 | 137 |

| Daily | 18 | 52 | 16 | 107 |

| Rarely | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Do you have leftovers? | ||||

| Never | Occasionally | Often | Rarely | |

| Hourly | 15 | 125 | 91 | 89 |

| Daily | 2 | 95 | 49 | 47 |

| Rarely | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Do you pay attention to the expiry date? | ||||

| No | Not sure | Yes | ||

| Hourly | 37 | 25 | 258 | |

| Daily | 10 | 6 | 177 | |

| Rarely | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| How much does your family throw away? | ||||

| 0% | 25–50% | 75–100% | ||

| Hourly | 211 | 103 | 6 | |

| Daily | 133 | 57 | 3 | |

| Rarely | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Time Spent on Social Media Sites | Are You Aware of the Seriousness of Food Waste? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Not Sure | Yes | ||

| <2 h | 10 | 9 | 147 | |

| 3–5 h | 15 | 12 | 186 | |

| 5 h+ | 16 | 20 | 102 | |

| Do you think that you use plans to minimize food waste in your daily life? | ||||

| No | Not sure | Yes | ||

| <2 h | 10 | 21 | 135 | |

| 3–5 h | 25 | 41 | 147 | |

| 5 h+ | 27 | 25 | 86 | |

| Do you decide on the quantity of food you will prepare? | ||||

| No, I don’t | Yes, but I overestimate | Yes, but I underestimate | Yes, I measure the exact amount I’ll use | |

| <2 h | 15 | 47 | 16 | 88 |

| 3–5 h | 30 | 64 | 16 | 103 |

| 5 h+ | 18 | 59 | 9 | 52 |

| Think Food Waste Is a Problem | Do You Think That You Use Plans to Minimize Food Waste in Your Daily Life? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Not Sure | Yes | ||

| No | 6 | 0 | 7 | |

| Not sure | 2 | 5 | 0 | |

| Yes | 55 | 84 | 366 | |

| How often do you undertake any actions to reduce the amount of food you throw away? | ||||

| Never | Occasionally | Often | Rarely | |

| No | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Not sure | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Yes | 12 | 177 | 277 | 39 |

| Do you decide on the quantity of food you will prepare? | ||||

| No, I don’t | Yes, but I overestimate | Yes, but I underestimate | Yes, I measure the exact amount I’ll use | |

| No | 1 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Not sure | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 62 | 162 | 39 | 242 |

| Do you have leftovers? | ||||

| Never | Occasionally | Often | Rarely | |

| No | 4 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| Not sure | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Yes | 15 | 219 | 136 | 135 |

| Awareness about the Seriousness of Food Waste | Use Plans to Minimize Food Waste in Your Daily Life? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Not Sure | Yes | ||

| No | 12 | 7 | 22 | |

| Not sure | 8 | 12 | 22 | |

| Yes | 43 | 70 | 329 | |

| When visiting a shop do you buy food according to a set meal plan? | ||||

| No | Not sure | Yes | ||

| No | 18 | 9 | 14 | |

| Not sure | 26 | 5 | 11 | |

| Yes | 152 | 59 | 231 | |

| What do you do with the leftovers? | ||||

| Discard them | Eat themnext day | Give them away | Freeze them | |

| No | 8 | 20 | 18 | 5 |

| Not sure | 8 | 33 | 22 | 10 |

| Yes | 60 | 328 | 186 | 88 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Osaili, T.M.; Obaid, R.S.; Alqutub, R.; Akkila, R.; Habil, A.; Dawoud, A.; Duhair, S.; Hasan, F.; Hashim, M.; Ismail, L.C.; et al. Food Wastage Attitudes among the United Arab Emirates Population: The Role of Social Media. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031870

Osaili TM, Obaid RS, Alqutub R, Akkila R, Habil A, Dawoud A, Duhair S, Hasan F, Hashim M, Ismail LC, et al. Food Wastage Attitudes among the United Arab Emirates Population: The Role of Social Media. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031870

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsaili, Tareq M., Reyad S. Obaid, Russul Alqutub, Rawya Akkila, Ala Habil, Ahlam Dawoud, Serin Duhair, Fayeza Hasan, Mona Hashim, Leila Cheikh Ismail, and et al. 2022. "Food Wastage Attitudes among the United Arab Emirates Population: The Role of Social Media" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031870

APA StyleOsaili, T. M., Obaid, R. S., Alqutub, R., Akkila, R., Habil, A., Dawoud, A., Duhair, S., Hasan, F., Hashim, M., Ismail, L. C., Al-Nabulsi, A. A., & Taha, S. (2022). Food Wastage Attitudes among the United Arab Emirates Population: The Role of Social Media. Sustainability, 14(3), 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031870