Can I Get Back Later or Turn It Off? Day-Level Effect of Remote Communication Autonomy on Sustainable Proactivity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

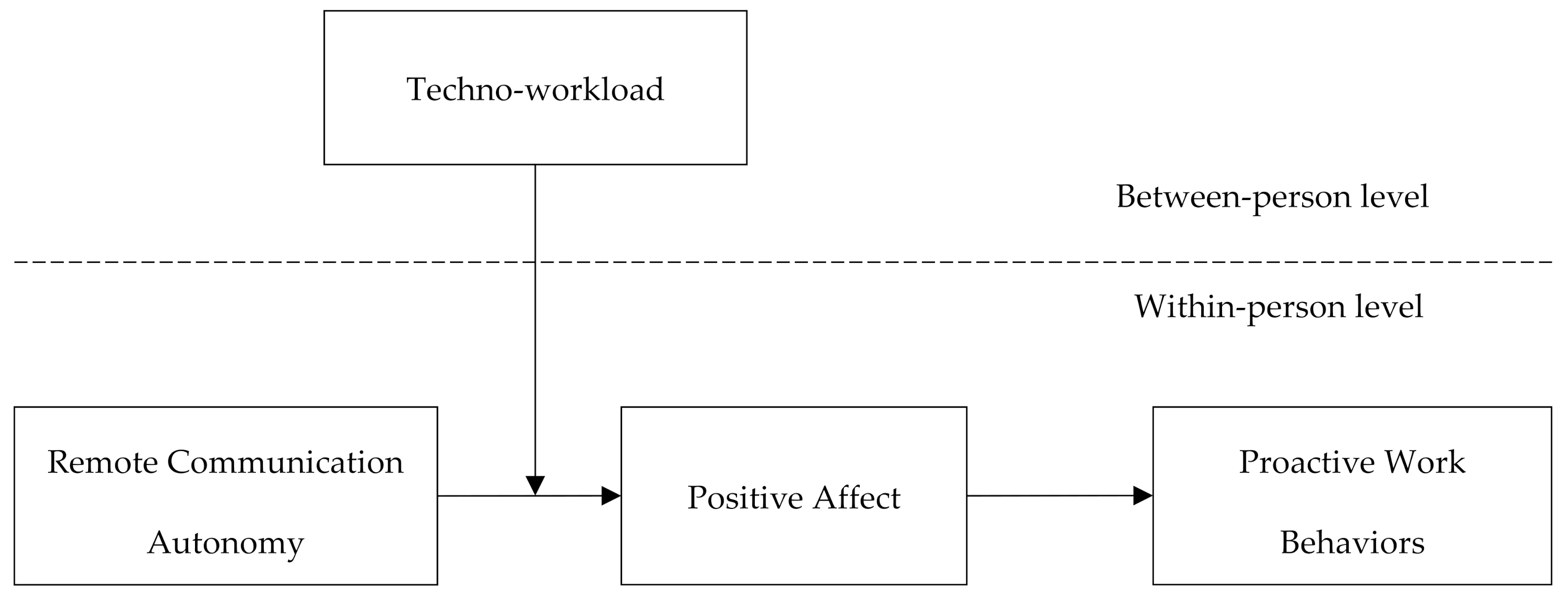

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Day-Level Effect of Remote Communication Autonomy on Positive Affect

2.2. Day-Level Indirect Effect of Remote Communication Autonomy on Proactive Work Behaviors via Positive Affect

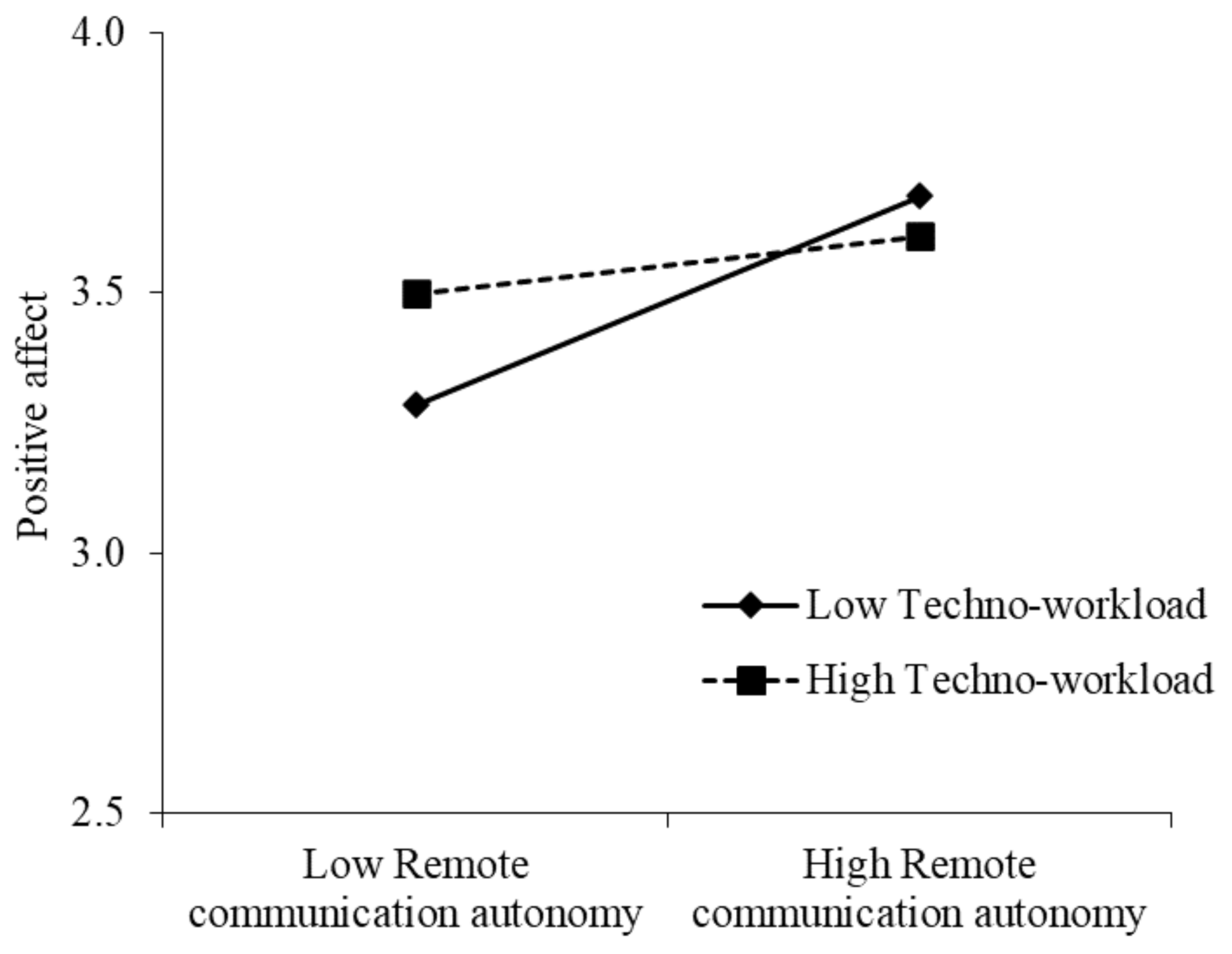

2.3. Person-Level Techno-Workload as a Cross-Level Moderator of the Day-Level Relationship

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Day-Level Measures

3.3. Person-Level Measures

3.4. Analytic Approach

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, D.S.; Orvell, A.; Briskin, J.; Shrapnell, T.; Gelman, S.A.; Ayduk, O.; Ybarra, O.; Kross, E. When chatting about negative experiences helps-and when it hurts: Distinguishing adaptive versus maladaptive social support in computer-mediated communication. Emotion 2020, 20, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.A.; Liu, Y.; Headrick, L. When work is wanted after hours: Testing weekly stress of information communication technology demands using boundary theory. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 518–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stich, J.F.; Tarafdar, M.; Cooper, C.L.; Stacey, P. Workplace stress from actual and desired computer-mediated communication use: A multi-method study. New Technol. Work Employ. 2017, 32, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosen, C.C.; Simon, L.S.; Gajendran, R.S.; Johnson, R.E.; Lee, H.W.; Lin, J. Boxed in by your inbox: Implications of daily email demands for managers’ leadership behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, E.; Woods, S.A.; Banks, A.P. Examining conscientiousness as a key resource in resisting email interruptions: Implications for volatile resources and goal achievement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 90, 407–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breaugh, J.A. The measurement of work autonomy. Hum. Relat. 1985, 38, 551–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N.; Belschak, F.D. When does transformational leadership enhance employee proactive behavior? The role of autonomy and role breadth self-efficacy. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Ashford, S.J. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Lee, T.W. The effects of autonomy and empowerment on employee turnover: Test of a multilevel model in teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfred, C.W.; Moye, N.A. Effects of task autonomy on performance: An extended model considering motivational, informational, and structural mechanisms. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beal, D.J.; Weiss, H.M.; Barros, E.; Macdermid, S.M. An episodic process model of affective influences on performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1054–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.A.; Campion, E.D.; Keeler, K.R.; Keener, S.K. Videoconference fatigue? Exploring changes in fatigue after videoconference meetings during COVID-19. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Staw, B.M., Cummings, L.L., Eds.; Elsevier Science/JAI Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Butts, M.M.; Becker, W.J.; Boswell, W.R. Hot buttons and time sinks: The effects of electronic communication during nonwork time on emotions and work-nonwork conflict. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 763–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trougakos, J.P.; Beal, D.J.; Green, S.G.; Weiss, H.M. Making the break count: An episodic examination of recovery activities, emotional experiences, and positive affective displays. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A.; Parker, S.K. A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shockley, K.M.; Gabriel, A.S.; Robertson, D.; Rosen, C.C.; Ezerins, M.E. The fatiguing effects of camera use in virtual meetings: A within-person field experiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 1137–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockey, G.R.J.; Earle, F. Control over the scheduling of simulated office work reduces the impact of workload on mental fatigue and task performance. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2006, 12, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadin, M.; Nordin, M.; Brostrom, A.; Hanson, L.L.M.; Westerlund, H.; Fransson, E.I. Technostress operationalised as information and communication technology (ICT) demands among managers and other occupational groups—Results from the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH). Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol.-Int. Rev. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Reinecke, L.; Mata, J.; Vorderer, P. Feeling interrupted-being responsive: How remote messages relate to affect at work. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Neveu, J.P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the COR: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragu-Nathan, T.S.; Tarafdar, M.; Ragu-Nathan, B.S.; Tu, Q. The consequences of technostress for end users in organizations: Conceptual development and empirical validation. Inform. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, A.K.; Ravlin, E.C.; Klaas, B.S.; Ployhart, R.E.; Buchan, N.R. When do high-context communicators speak up? Exploring contextual communication orientation and employee voice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1498–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglbauer, B. Under what conditions does job control moderate the relationship between time pressure and employee well-being? Investigating the role of match and personal control beliefs. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 730–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledow, R.; Schmitt, A.; Frese, M.; Kuhnel, J. The affective shift model of work engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mignonac, K.; Herrbach, O. Linking work events, affective states, and attitudes: An empirical study of managers’ emotions. J. Bus. Psychol. 2004, 19, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trougakos, J.P.; Hideg, I.; Cheng, B.H.; Beal, D.J. Lunch breaks unpacked: The role of autonomy as a moderator of recovery during lunch. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, Y.; Liao, H.; Raub, S.; Han, J.H. What it takes to get proactive: An integrative multilevel model of the antecedents of personal initiative. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Walkowiak, A.; Thommes, M.S. How can mindfulness be promoted? Workload and recovery experiences as antecedents of daily fluctuations in mindfulness. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 2018, 91, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albrecht, S.L.; Green, C.R.; Marty, A. Meaningful Work, job resources, and employee engagement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P.D.; Edwards, J.R.; Sonnentag, S. Stress and well-being at work: A century of empirical trends reflecting theoretical and societal influences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, L.L.; Cho, E.; Dumani, S. The effect of positive work reflection during leisure time on affective well-being: Results from three diary studies. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Bindl, U.K.; Strauss, K. Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, R. Autonomy and citizenship behavior: A moderated mediation model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; Glomb, T.M.; Shen, W.; Kim, E.; Koch, A.J. Building positive resources: Effects of positive events and positive reflections on work stress and health. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1601–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lanaj, K.; Johnson, R.E.; Wang, M. When lending a hand depletes the will: The daily costs and benefits of helping. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1097–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Boyajian, M.E.; O’Brien, K.E. Perceived victimization as the mechanism underlying the relationship between work stressors and counterproductive work behaviors. Hum. Perform. 2016, 29, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, A.E.; Mazzola, J.J.; Bauer, J.; Krueger, J.R.; Spector, P.E. Can work make you sick? A meta-analysis of the relationships between job stressors and physical symptoms. Work Stress 2011, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailenson, J.N. Nonverbal overload: A theoretical argument for the causes of Zoom fatigue. Technol. Mind Behav. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, Y.; Headrick, L. Daily micro-breaks and job performance: General work engagement as a cross-level moderator. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 772–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faelens, L.; Hoorelbeke, K.; Soenens, B.; Gaeveren, K.; De Marez, L.; De Raedt, R.; Koster, E.H.W. Social media use and well-being: A prospective experience-sampling study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Song, Z. Give and take: An episodic perspective on leader-member exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, A.C.; He, W.; Yam, K.C.; Bolino, M.C.; Wei, W.; Houtson, L. Good actors but bad apples: Deviant consequences of daily impression management at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puranik, H.; Koopman, J.; Vough, H.C. Excuse me, do you have a minute? An exploration of the dark- and bright-side effects of daily work interruptions for employee well-being. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 1867–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.; Lonner, W.J.; Thorndike, R. Cross-Cultural Research Methods; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon, A.; Jorm, A.F.; Christensen, H.; Korten, A.E.; Jacomb, P.A.; Rodgers, B. A short form of the positive and negative affect schedule: Evaluation of factorial validity and invariance across demographic variables in a community sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1999, 27, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, P.; Houston, L.; Cho, J. Not too tired to be proactive: Daily empowering leadership spurs next-morning employee proactivity as moderated by nightly sleep quality. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 2367–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Jex, S.M. Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal conflict at work scale, organizational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sherf, E.N.; Vijaya, V.; Gajendran, R.S. Too busy to be fair? The effect of workload and rewards on managers’ justice rule adherence. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 469–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Zyphur, M.J.; Zhang, Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ilies, R.; Liu, X.Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X. Why do employees have better family lives when they are highly engaged at work? J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Curran, P.J.; Bauer, D.J. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2006, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Halbesleben, J.R.B. Productive and counterproductive job crafting: A daily diary study. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hetland, J. Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matusik, S.F.; Mickel, A.E. Embracing or embattled by converged mobile devices? Users’ experiences with a contemporary connectivity technology. Hum. Relat. 2011, 64, 1001–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabitza, F.; Locoro, A.; Ravarini, A. Trading off between control and autonomy: A narrative review around de-design. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2020, 39, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, S.; Sonnentag, S.; Niessen, C.; Zapf, D. Diary studies in organizational research. J. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 9, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N.; Davis, A.; Rafaeli, E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 579–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wheeler, L.; Reis, H.T. Self-recording of everyday life events: Origins, types, and uses. J. Personal. 1991, 59, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Daily Variables | Within-Person Variance (e2) | Between-Person Variance (r2) | Proportion of Within-Person Variance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep quality (Control) a | 0.55 | 0.16 | 77.5% |

| Remote communication autonomy b | 0.17 | 0.20 | 45.9% |

| Positive affect b | 0.14 | 0.30 | 31.8% |

| Proactive work behaviors c | 0.21 | 0.27 | 43.8% |

| Variable | Mean | SD w | SD b | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day-level | |||||||||

| 1. Remote communication autonomy | 3.71 | 0.61 | 0.47 | — | 0.65 *** | 0.68 *** | 0.14 | −0.28 * | 0.59 *** |

| 2. Positive affect | 3.52 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.51 *** | — | 0.75 *** | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.37 ** |

| 3. Proactive work behaviors | 3.55 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.47 *** | 0.63 *** | — | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.39 *** |

| 4. Sleep quality (Control) | 3.25 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.09 * | 0.19 *** | 0.11 ** | — | 0.01 | 0.23 * |

| Person-level | |||||||||

| 5. Techno-workload | 2.98 | — | 0.57 | −0.18 *** | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | — | −0.33 ** |

| 6. Job autonomy (Control) | 3.54 | — | 0.54 | 0.41 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.13 *** | −0.33 *** | — |

| Measure | Positive Affect | Proactive Work Behaviors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Day-level | ||||||

| Intercept | 2.25 *** | 0.43 | 3.52 *** | 0.06 | 2.15 *** | 0.43 |

| Sleep quality | 0.10 *** | 0.03 | 0.10 ** | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Remote communication autonomy | 0.16 ** | 0.06 | 0.20 *** | 0.04 | ||

| Positive affect | 0.29 *** | 0.07 | ||||

| Person-level | ||||||

| Job autonomy | 0.36 ** | 0.12 | 0.43 *** | 0.12 | 0.39 ** | 0.12 |

| Techno-workload | 0.19 | 0.10 | ||||

| Remote communication autonomy × techno-workload | −0.21 ** | 0.07 | ||||

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.39 | 0.36 | 0.42 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Du, J.; Choi, J.N.; Li, Y. Can I Get Back Later or Turn It Off? Day-Level Effect of Remote Communication Autonomy on Sustainable Proactivity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031856

Liu Y, Du J, Choi JN, Li Y. Can I Get Back Later or Turn It Off? Day-Level Effect of Remote Communication Autonomy on Sustainable Proactivity. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031856

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yujing, Jing Du, Jin Nam Choi, and Yuan Li. 2022. "Can I Get Back Later or Turn It Off? Day-Level Effect of Remote Communication Autonomy on Sustainable Proactivity" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031856

APA StyleLiu, Y., Du, J., Choi, J. N., & Li, Y. (2022). Can I Get Back Later or Turn It Off? Day-Level Effect of Remote Communication Autonomy on Sustainable Proactivity. Sustainability, 14(3), 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031856