Major Shifts in Sustainable Consumer Behavior in Romania and Retailers’ Priorities in Agilely Adapting to It

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The major shifts in sustainable consumer behavior (increased consumer willingness to move towards sustainable products as well as to change their shopping habits in order to reduce their impact on the environment; enhanced consumer awareness about the key role consumers play in influencing sustainable production and consumption by adopting greener purchasing behaviors and attitudes; the reduction in the discrepancy between consumers’ attitudes and their behavior concerning their sustainable shopping decisions on the one hand and their intentions regarding the purchase of sustainable products on the other; increasing consumers’ awareness of the concepts of UN SDGs, Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0) on the Romanian retail market within the context of digital transformation and of Green European Deal, and

- Retailers’ priorities in agilely adapting to these significant evolutions, by identifying risk areas (associated with: the disruptive technologies, consumers’ perceptions with regard to the outcome of investments made by the supermarket chain in sustainability, consumers’ uncertainty and anxiety, consumers’ resistance to change caused by convenience and especially price) and opportunities (the translation of the consumers’ uncertainty into trust; increased focus on responding to sustainability as an increasingly personal value of consumers; partnerships with suppliers that develop sustainable products; leveraging the e-commerce channel to provide new opportunities for circular consumption; targeting consumers with agile messages and tailored issues, responding to their needs for better information and education, and aiding them to adopt more sustainable lifestyles and to make informed choices in the omnichannel world).

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Relationship between the Concepts of Circular Economy, Sustainability, and Sustainable Development

2.2. Digitalization and Its Influence on the Retail Industry

2.2.1. Consumers’ Relationship and Engagement within Digital Transformation

2.2.2. Retailers’ Phygital Strategies and the Sustainable Smart Store of the Future

2.3. The Discrepancy between Consumers’ Attitudes towards Sustainable Consumption and Their Behavior in Purchasing Sustainable Products. The Need for Understanding Retailers’ Sustainability Journeys

2.3.1. Resolving the Challenging Green Shopper Dilemma

2.3.2. Consumers’ Decision-Making Impacted by Their Perspective towards Sustainability. Helping Shoppers Make Sustainable Choices

2.3.3. Prioritizing Sustainability in the Consumer Sector: Purposeful Retail and Shopping

2.3.4. Meeting and Exceeding Consumers’ Expectations by Providing Improved Experience Using the Lens of Sustainability

2.4. Consumers’ Perspective in the World’s Largest Market towards Sustainable Consumption

2.4.1. Global Consumers’ Perception of the Sustainability Imperative

2.4.2. Continuous Acceleration and Expansion of the Chinese Consumers’ Trends Existing Earlier in Time, Based on Improving Consumer Experience

2.4.3. China’s Sustainable Future Is Significantly Challenging the Other Main Global Actors, and Not Only Them

2.5. The Romanian Retail Sector’s Key Role in Sustainable Production and Consumption, and the Increasing Role of Sustainable Consumer Behavior in Romania

2.5.1. The Romanian Retail Market, an Important Market for Supermarket Chains

2.5.2. Romanian Green Consumers and Implementation of Sustainable Development Policies on the Romanian Retail Market

3. Hypothesis Development

- (a)

- Considering existing evidence: the practitioner experience mentioned earlier, the literature review (including gaps identified by us and presented in each area of the literature), as well as our own prior work. With regard to our prior recent work, it is worth remembering the aforementioned research on Romanian consumers’ perceptions of Artificial Intelligence [29] and on retailers’ need to become and remain consumers’ trusted advisors and agile to consumers’ changing behaviors in the current VUCA time more than ever [28]. It is also important to consider how necessary it is to take into account how and when to assess consumers’ satisfaction on the basis of comparisons between actual purchases and preset standards and expectations, considering the effect–effort relationship or the purchases’ performance [171]. And that within the context in which: a Big Data analysis of consumer satisfaction following the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the customer end of retail supply chains in a main investing EU country in Romania revealed a general and significant decline in consumer satisfaction [172]; the relationship between satisfaction and loyalty can occur through more or less important mediators, such as perceived switching costs or perceived lack of attractiveness of alternative offerings [173]; the choices of today’s consumers, expanded by the mix of traditional and digital marketing, are putting pressures on both retailers and their suppliers to better drive consumers’ loyalty by building better brand partnerships in order to cross-share more effectively consumers’ information within their recently disrupted supply chains, increase consumers’ engagement and connection, and improve their experience based on a deeper understanding of consumer behavior through richer data clarifying consumers’ value [174]. It is interesting to note that the above-mentioned second annual IBM, Armonk, NY, USA and US National Retail Federation, Washington, DC, global consumer retail study published in January 2022 confirmed what we revealed in our aforementioned research [29] with regard to the role of AI in the way retailers can significantly drive value.

- (b)

- Using reasoning to deduce what will happen in our specific context of interest: by identifying our problem of interest with regard to shifts in sustainable consumer behavior and retailers’ need for deep consumer insights in their agile adaptation, while enabling sustainable business models; determining the significance of this problem (the extent to which consumers will benefit from our findings; the extent to which the findings will be applicable to retail business practice and consumer education, etc.); determining the feasibility of studying the significant problem of interest.

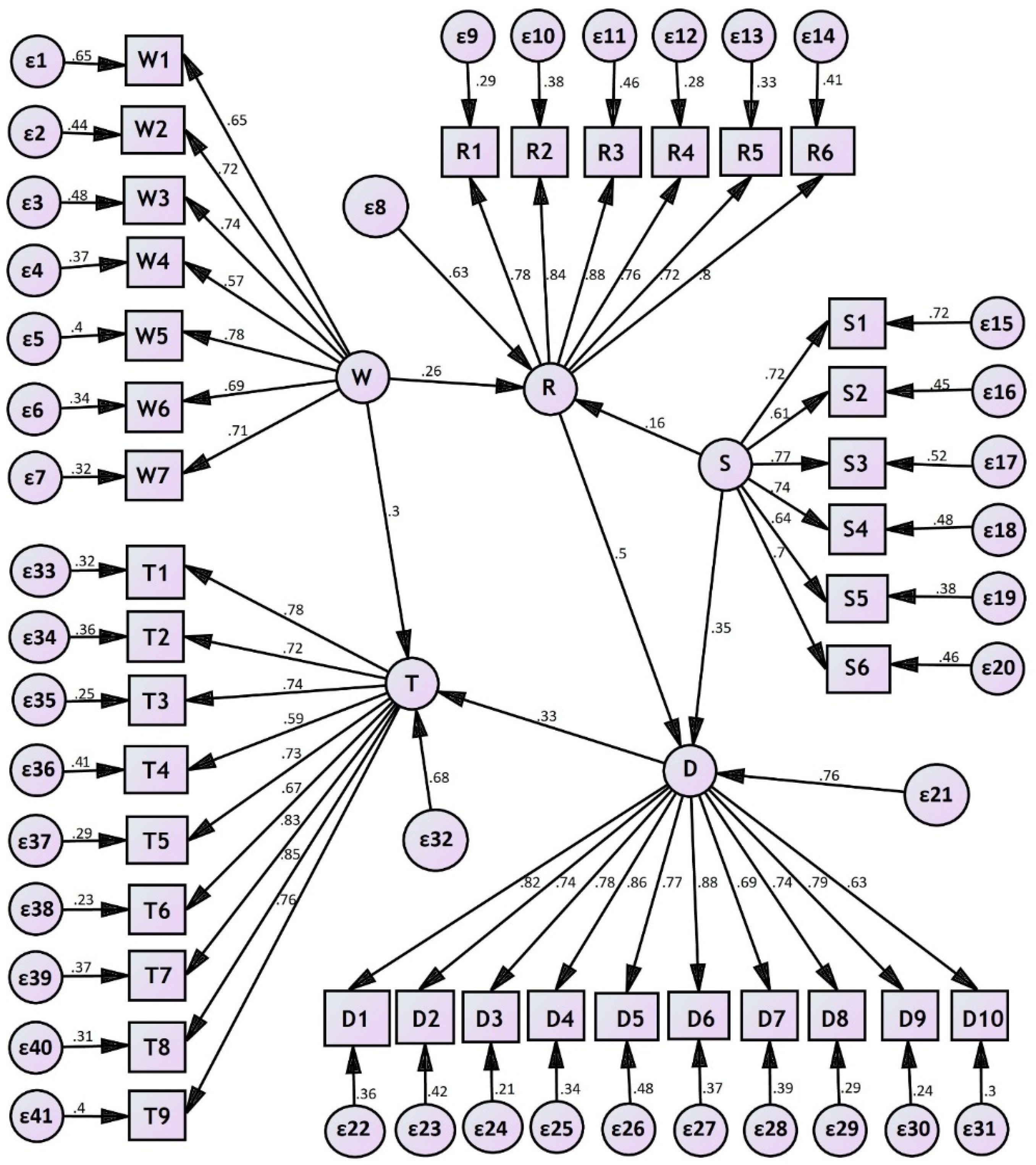

- Depends on “Retailers’ sustainability agenda, including by fulfilling consumers’ sustainability demands with new products and processes” (“S”, an endogenous variable allowing the statements of the hypotheses H2 and H3 below), the “S” construct appearing as a moderating factor with regard to the “R” and “D” constructs;

- Impacts “Retailers’ digital transformation to aid consumers to adopt more sustainable lifestyles and to make informed choices in the omnichannel world” (“D”), being a mediating factor between the “W” and “D” constructs.

4. Research Methods

5. Results and Discussions

The Latent Variables

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary

- As an EU member country, Romania has a strategic location at the crossroads of three great markets (the EU, the CIS, and the Middle East), is a leading destination in CEE for foreign direct investment, and is recognized for the similarities of its distribution and sales channels, the range of its retail outlets, and the local retail market dominance in the Big Box segment by reputed major retailers;

- Romania’s e-commerce market is continuing to undergo a spectacular evolution, including from the point of view of the long-standing and memorable traditional relationship between Romania and China, which was confirmed also more recently by Romanian consumers, who prefer to buy online from stores in China rather than from stores in EU member states and the USA, while in the top foreign platforms preferred by Romanians AliExpress/Alibaba Group ranks second, in front of the e-commerce giant Amazon.

- Consumers perceive how retailers are becoming step by step more aware of the need to manage and reduce consumers’ resistance to change through the range of products offered, the merchandising techniques used, and the assistance offered in the phygital space, confirming in this way the continuous integration of sustainability into their operational and strategic activities.

- Consumers perceive how retailers are paying more attention to sustainability as a personal value of consumers.

- Consumers perceive that retailers already have a significant sustainability agenda.

- Consumers perceive an increased concentration of retailers on digitizing processes (by creating a digital representation of physical objects or attributes), including the mode of retailer–consumer communication (social media, text messages, phone, etc.), and the enablement of new business models with the help of new disruptive technologies (valorizing the digitized data and improving consumer experience).

- Consumers feel the need for consumers’ uncertainty and anxiety to be better addressed by retailers within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, by reducing the associated risks, and for retailers to confirm their honesty and transparency by asking for and acting on consumers’ feedback and translating consumers’ uncertainty into the trust that consumers expect.

- The research developed a clear understanding of:

- Consumers’ increasing awareness of their important role in impacting sustainable production and consumption by adopting greener behavior and attitudes, mainly the digital natives who are more proficient in the use of new technologies, and thereby enabling the smoothing of sustainable consumption;

- Retailers’ challenge of targeting consumers with agilely adapted messages and issues (based on the new technologies disrupting retailers’ traditional strategy of using distribution channels to deliver the products within the digital ecosystems) strengthening brand perception on sustainability and answering to consumers’ needs for better information and education so as to reduce the difference between the reality of their behavior and attitudes on the one hand, and their reported purchasing intentions of sustainable products (which purchases were performed better online versus in-store) on the other.

6.2. Implications

6.3. Limitations

- (a)

- Similar to other recent studies based on objective questionnaires that are answered after a face-to-face interview, the answers came rather from young people. Thus, over half of the respondents (more precisely 52.9%) were people up to 35 years old, and over 82% were up to 45 years old—in other words: Xennials + Millennials + Gen Z. Only 10.3% of respondents were between 46–55 years old and just over 6% were between 46–65 years, the weakest-represented segment being ‘over 66 years old’, in which we find less than 1 percent of the total number of respondents. We made these clarifications out of a desire to explain the degree of representativeness in our study. The explanations have several hypotheses, the most important being related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the way in which the elderly choose to protect themselves by limiting their exposure time in public spaces.

- (b)

- Although we considered the feedback obtained after the ‘face validity technique’, as well as the pilot test, we consider that some questions may require a certain degree of knowledge of the concerns related to circular economy, sustainability, and sustainable development. For this reason, those questions have been adjusted and additional explanations have been added of some specialized terms or of some legislative initiatives. The questionnaire was addressed to Romanian clients, and by translating it into English some terms may seem less intelligible.

- (c)

- Another weakness is the size of the focus groups and the pilot test group, for which larger sizes would have been preferred. At the same time, following the adjustments, the W, R, and S constructs were left with only 7, 6 and 6 items, respectively. These are relatively small numbers, which can also affect Cronbach’s alpha values. However, the whole process of building items is a strong point, with many of the items being built based on interviews specially designed for this study. The dimensions identified in this study represent novelty elements in specialized research.

- (d)

- Another strong point that we would like to mention is the above-mentioned conducting of in-person interviews, a superior procedure to online interviews, where there is no adequate control over the seriousness of the respondents. This strength, at the same time, is a limitation, if we think of those people who, being fearful, interacted less or even avoided shopping in stores, as previously stated.

6.4. Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Narisetti, R. Author Talks: April Rinne on Finding Calm and Meaning in a World of Flux. McKinsey & Company Featured Insights. 2021, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-on-books/author-talks-april-rinne-on-finding-calm-and-meaning-in-a-world-of-flux (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Islam, S.; Yuhan, C. Towards an Environmental Sociology of Sustainability, Editorial. Sustainability. 2018. Sustainability through the Lens of Environmental Sociology. Special Issue, Editor Md Saidul Islam. 2018, pp. 226, 231. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/books/pdfview/book/543 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Perella, M.; Yonkers, C. Brands Share Insights on Closing the Intention-Action Gap. Sustainable Brands. 4 November 2021. Available online: https://sustainablebrands.com/read/behavior-change/bottling-the-secret-sauce-brands-share-insights-on-closing-the-intention-action-gap (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaud, D.; Laperche, B. Circular Economy, Industrial Ecology and Short Supply Chain; Wiley-ISTE: London, UK, 2016; Volume 4, p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A Review on Circular Economy: The Expected Transition to a Balanced Interplay of Envi-Ronmental and Economic Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 114, 11–32. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959652615012287 (accessed on 31 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Lieder, M.; Rashid, A. Towards circular economy implementation: A comprehensive review in context of manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 115, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repo, P.; Anttonen, M. Emerging Consumer Perspectives on Circular Economy. In Proceedings of the 13th Nordic Environmental Social Science Conference HopefulNESS, Tampere, Finland, 6–8 June 2017; Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/56580737/Repo_Anttonen_Circular_Economy_Hopefulness_2017-with-cover-page-v2.pdf? (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Moreau, V.; Sahakian, M.; Van Griethuysen, P.; Vuille, F. Coming Full Circle: Why Social and Institutional Dimensions Matter for the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 497–506. Available online: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/jiec.12598 (accessed on 31 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Bi, J.; Moriguichi, Y. The circular economy: A new development strategy in China. J. Ind. Ecol. 2006, 10, 4–8. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.894.583&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borrello, M.; Caracciolo, F.; Lombardi, A.; Pascucci, S.; Cembalo, L. Consumers’ Perspective on Circular Economy Strategy for Reducing Food Waste. Sustainability 2017, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCarthy, S.; Thomas, S.L.; Randle, M.; Bestman, A.; Pitt, H.; Cowlishaw, S.; Daube, M. Women’s gambling behaviour, product preferences, and perceptions of product harm: Differences by age and gambling risk status. Harm Reduct. J. 2018, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekins, P.; Domenech, T.; Drummond, P.; Bleischwitz, R.; Hughes, N.; Lotti, L. “The Circular Economy: What, Why, How and Where”, Background paper for an OECD/EC Workshop on 5 July 2019 within the workshop series “Managing environmental and energy transitions for regions and cities”, Paris. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/Ekins-2019-Circular-Economy-What-Why-How-Where.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Maryville University. Sustainability vs. Sustainable Development: Examining Two Important Concepts, Maryville University Blog, St. Louis, Missouri. 2021. Available online: https://online.maryville.edu/blog/sustainability-vs-sustainable-development/ (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Circular Ecology. An Introduction to Sustainability and Sustainable. Circular Ecology. April 2020. Available online: https://circularecology.com/introduction-to-sustainability-guide.html (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- European Commission. What is Horizon 2020? Programmes. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/what-horizon-2020 (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- European Commission. Circular Economy Research and Innovation-Connecting Economic & Environmental Gains. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. August 2017, p. 3. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/sites/default/files/ce_booklet.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, European Commission, Brussels, 11.12.2019 COM(2019) 640 Final, The European Green Deal. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/european-green-deal-communication_en.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, European Commission, Brussels, 11.3.2020 COM(2020) 98 final, A new Circular Economy Action Plan. For a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:9903b325-6388-11ea-b735-01aa75ed71a1.0017.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Hallstedt, S.I.; Isaksson, O.; Öhrwall Rönnbäck, A. The Need for New Product Development Capabilities from Digitalization, Sustainability, and Servitization Trends. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Het Groene Brein. How Is a Circular Economy Different from a Linear Economy? Kenniskaarten. 2020. Available online: https://kenniskaarten.hetgroenebrein.nl/en/knowledge-map-circular-economy/how-is-a-circular-economy-different-from-a-linear-economy/ (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Government of The Netherlands. From a Linear to a Circular Economy. In Circular Economy; 2021. Available online: https://www.government.nl/topics/circular-economy/from-a-linear-to-a-circular-economy (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- SB Insight. Sustainable Brand Index™. Rankings & Results. 2021. Available online: https://www.sb-index.com/ (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- SB Insight. Are We Becoming More Ego? SB Insight Blog. 22 April 2021. Available online: https://www.sb-index.com/blog/2020/4/22/are-we-becoming-more-ego (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Wigder, Z.D.; Lipsman, A.; Davidkhanian, S. A New Era in Retail and Ecommerce is Emerging. eMarketer. 2021. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/new-era-retail-ecommerce-emerging? (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Hatami, H.; Hilton Segel, L. What Matters Most? Five Priorities for CEOs in the Next Normal. McKinsey & Company Strategy & Corporate Finance Insights, Special Report. 2021, p. 1. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/what-matters-most-five-priorities-for-ceos-in-the-next-normal? (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- WWF Singapore. Study Reveals a Clear, Unmet Consumer Demand for Sustainable Products in Singapore: Accenture and WWF, World Wide Fund for Nature Singapore. 16 March 2021. Available online: https://www.wwf.sg/study-reveals-a-clear-unmet-consumer-demand-for-sustainable-products-in-singapore-accenture-and-wwf/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Purcarea, I.M.; Purcarea, I.; Purcarea, T. The Test of VUCA Time for Retail 4.0 Impacted by the Industry 4.0 Technologies, by Creating Customers’ Real-Time Digital Experience, Faster Recovering from the Pandemic, and Adapting to the Next Normal, Book Chapter published in Monograph of Under the Pressure of Digitalization: Challenges and Solutions at Organizational and Industrial Levels; Edu, T., Schipor, G.L., Vancea, D.P.C., Zaharia, R.M., Eds.; Under the Pressure of Digitalization: Challenges and Solutions at Organizational and Industrial Levels; Filodiritto Publisher: Bologna, Italy, 2021; pp. 40–45. ISBN 979-12-80225-27-6. [Google Scholar]

- Purcărea, T.; Ioan-Franc, V.; Ionescu, S.A.; Purcărea, I.M. The Profound Nature of Linkage Between the Impact of the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Retail on Buying and Consumer Behavior and Consumers’ Perceptions of Artificial Intelligence on the Path to the Next Normal. Amfiteatru Econ. 2021, 23, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, R. Digital Transformation in Product Development, Institute for Digital Ttransformation. 1 May 2019. Available online: https://www.institutefordigitaltransformation.org/digital-transformation-in-product-development/ (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Factory. What is the role of digitalization in business growth? Factory Blog. 27 September 2021. Available online: https://factory.dev/blog/digitalization-business-growth (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Angel, S. What’s the Difference between a Project and a Product? Accenture Blog. 26 May 2021. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/us-en/blogs/software-engineering-blog/whats-the-difference-between-a-project-and-a-product (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Gartner for Marketers. Creating a High-Impact Customer Experience Strategy. 22 November 2019. Available online: https://emtemp.gcom.cloud/ngw/globalassets/en/marketing/documents/creating-a-high-impact-customer-experience-strategy-gartner-for-marketers-11-22-2019.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Purcarea, I.M. Marketing 5.0, Society 5.0, Leading-Edge Technologies, New CX, and New Engagement Capacity within the Digital Transformation. Holist. Mark. Manag. 2021, 11, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Change Reviews Team. Digital Adoption Meaning, Change-Reviews. 12 November 2021. Available online: https://www.change-reviews.com/digital-adoption-meaning/ (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Remes, J.; Manyika, J.; Smit, S.; Kohli, S.; Fabius, V.; Dixon-Fyle, S.; Nakaliuzhnyi, A. The Consumer Demand Recovery and Lasting Effects of COVID-19. McKinsey Global Institute Report. 2021, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/the-consumer-demand-recovery-and-lasting-effects-of-covid-19? (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Kerravala, Z. Bolt SSO Commerce Redefines the Customer Experience. ZK Research. 2021, pp. 2, 4, 7, 8. Available online: https://www.bolt.com/landing/analyst-zk-research-sso-redefines-cx/ (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Atluri, V.; Baig, A.; Rao, S. Accelerating the impact from a tech-enabled transformation. McKinsey Digital. 2019. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/advanced-electronics/our-insights/accelerating-the-impact-from-a-tech-enabled-transformation (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution: What It Means, How to Respond. The World Economic Forum Agenda, 14 January, First Published in Foreign Affairs. 2016. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/ (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- European Commission. Industry 5.0—Towards a Sustainable, Human-Centric and Resilient European Industry. Research and Innovation Paper Series Policy Brief. 2021, pp. 3, 27, 29, 46. Available online: https://kyklos40project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/EC_Industry_5.0_Report.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Scott, M. The Regulation on the Horizon: Sustainable Finance & Reporting; Reuters Events Sustainable Business 2021, Dawn of a New Reporting Era, Regulation, Transparency, Harmonisation, 25–26 November 2021, Online. p. 3. Available online: https://reutersevents.com/events/reporting/brochure-thank-you.php (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Accorsi, R.; Manzini, R. (Eds.) Sustainable Food Supply Chains: Planning, Design, and Control through Interdisciplinary Methodologies, 1st ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 12 June 2019; pp. XIII–XIV. [Google Scholar]

- European Retail Academy. Thematic University Network. ERA. 9 October 2017. Available online: http://european-retail-academy.org/AgriBusinessForum/index.php?start=25 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- SANABUNA. Working meeting at the headquarters of the National R&D Institute for Food Bioresources, IBA Bucharest, Romania. SANABUNA International Congress. 17 November 2017. Available online: https://www.sanabuna.ro/working-meeting-at-the-headquarters-of-the-national-rd-institute-for-food-bioresources-iba-bucharest-romania/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Purcarea, T. Road Map for the Store of the Future, World Premiere, 4 May 2015, at SHOP 2015, Expo Milano 2015. Rom. Distrib. Comm. Mag. 2015, 6, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Purcarea, T. Education and Communications within the Circular Economy, the Internet of Things, and the Third Industrial Revolution. Challenges ahead the “Competency based” Education Model. Rom. Distrib. Comm. Mag. 2014, 5, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell-Alcocer, A.; Romero-Luis, J.; Gertrudix, M. A Methodological Assessment Based on a Systematic Review of Circular Economy and Bioenergy Addressed by Education and Communication. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendle, N.T.; Farris, P.W.; Pfeife, P.E.; David, J.; Reibstein, D.J. Marketing Metrics. The Manager’s Guide to Measuring Marketing Performance, 3rd ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 43–55, 164, 169, 352, 356–358. [Google Scholar]

- Charm, T.; Perrey, J.; Poh, F.; Ruwadi, R. 2020 Holiday Season: Navigating Shopper Behaviors in the Pandemic. McKinsey & Company Report. 5 November 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/solutions/periscope/our-insights/surveys/2020-holiday-season-navigating-shopper-behaviors-in-the-pandemic (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Charm, T.; Dhar, R.; Haas, S.; Liu, J.; Novemsky, N.; Teichner, W. Understanding and Shaping Consumer Behavior in the Next Normal, McKinsey & Company, Marketing and Sales. 24 July 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/understanding-and-shaping-consumer-behavior-in-the-next-normal (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- EDF + Business. The Roadmap to Sustainable E-commerce. How the World’s Biggest e-Commerce Retailers Can Use Their Influence to Benefit the Environment and Their Bottom Lines, Report by EDF + Business, Part of Environmental Defense Fund (EDF). 2020. Available online: https://business.edf.org/insights/the-roadmap-to-sustainable-e-commerce/ (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Accenture. Store of Tomorrow. A New Integrated Vision for the Near Future of Retailing. 2021, pp. 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 15, 16. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/PDF-168/Accenture-Store-Tomorrow-POV.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Laska, K. How the Industry Can Power a Sustainable and Digital Future. EuroShop Magazine. 28 April 2021. Available online: https://mag.euroshop.de/en/2021/04/sustainable-smart-stores-the-concept-of-the-future/ (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Purcarea, T. The Future of Retail Impacted by the Smart Phygital Era. Rom. Distrib. Comm. Mag. 2018, 9, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Purcarea, T.; Purcarea, I.; Purcarea, A. The Impact of an Improved Smartphone App’s User Ex-perience on the Mobile Customer Journey on the Romanian Market. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economics and Social Sciences, Bucharest, Romania, 20 November 2018; Volume 1, pp. 579–588. [Google Scholar]

- Purcarea, T. Retailers under Pressure of Faster Adaptation to the New Marketing Environment. Rom. Distrib. Comm. Mag. 2020, 11, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Purcarea, T. Retailers’ current reflecting and learning from challenges. Rom. Distrib. Comm. Mag. 2020, 11, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner. Leadership Vision for 2022. Gartner for IT, Top 3 Strategic Priorities for Data and Analytics Leaders. 2021. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/information-technology/insights/leadership-vision-for-data-and-analytics (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Gartner. Becoming Composable: A Gartner Trend Insight. Gartner for IT Leaders. 17 September 2021. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/doc/becoming-composable-gartner-trend-insight-report (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Jurisic, N.; Lurie, M.; Risch, P.; Salo, O. Doing vs. Being: Practical Lessons on Building an Agile Culture. McKinsey & Company. 4 August 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/doing-vs-being-practical-lessons-on-building-an-agile-culture (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Briedis, H.; Kronschnabl, A.; Rodriguez, A.; Ungerman, K. Adapting to the next normal in retail: The customer experience imperative. McKinsey & Company. 14 May 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/adapting-to-the-next-normal-in-retail-the-customer-experience-imperative (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- BIO Intelligence Service. Policies to Encourage Sustainable Consumption, Final Report Prepared for European Commission (DG ENV). 2012, pp. 7, 9–14, 254–255. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/pdf/report_22082012.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Consumer Goods Forum E2E. CGF E2E Co-Chair Talks Product Data, Industry Collaboration, and Digitization in New Year Interview, The Consumer Goods Forum, End-to-End Value Chain. 29 November 2021. Available online: https://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/news_updates/cgf-e2e-co-chair-talks-product-data-industry-collaboration-and-digitisation-in-new-interview/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- GS1 Netherlands. Tom Rose (SPAR): ‘Better data for better interaction with the consumer’. GS1 Magazine. 10 November 2021. Available online: https://magazine.gs1.nl/gs1-magazine-spar/spar (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Schrader, U.; Thøgersen, J. Putting Sustainable Consumption into Practice. J. Consum. Policy 2011, 34, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Terlau, W.; Hirsch, D. Sustainable Consumption and the Attitude-Behaviour-Gap Phenomenon-Causes and Measurements towards a Sustainable Development. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2015, 6, 59–174. Available online: http://centmapress.ilb.uni-bonn.de/ojs/index.php/fsd/article/view/634/500 (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Kahneman, D. Of 2 Minds: How Fast and Slow Thinking Shape Perception and Choice [Excerpt]. Scientific American. 2012. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/kahneman-excerpt-thinking-fast-and-slow/ (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Gupta, S.; Ogden, D.T. The Attitude-Behavior Gap in Environmental Consumerism. APUBEF Proceedings-Fall. 2006, pp. 199–206. Available online: http://www.nabet.us/Archives/2006/f%2006/APUBEF%20f2006.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Johnstone, M.-L.; Tan, L.P. Exploring the Gap Between Consumers’ Green Rhetoric and Purchasing. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzan, G.; Cruceru, A.F.; Bălăceanu, C.T.; Chivu, R.-G. Consumers’ Behavior Concerning Sustainable Packaging: An Exploratory Study on Romanian Consumers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalando. How the Industry and Consumers Can Close the Sustainability Attitude-Behavior Gap in Fashion. Attitude-Behavior Gap Report. 2021, pp. 1–36. Available online: https://corporate.zalando.com/sites/default/files/media-download/Zalando_SE_2021_Attitude-Behavior_Gap_Report_EN.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- McCullagh, J. Destination Zero: The Latest Consumer Trends around Sustainability, Think with Google, Consumer Insights. February 2020. Available online: https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/intl/en-gb/consumer-insights/consumer-trends/destination-zero-latest-consumer-trends-around-sustainability/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- GfK. Understanding Today’s Green Shopper Dilemma: Eco-Consciousness vs. Consumerism. GfK Blog. 2020. Available online: https://digital.gfk.com/understanding-todays-green-consumer (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Centre for Sustainable Fashion. Are Chinese consumers ready for sustainable fashion? VOGUEBUSINESS. 20 December 2021. Available online: https://mobile.twitter.com/sustfash/status/1472908896528437253 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chopra, M. How Sustainability Can Make a Product Stand out. Schroders Economic Insights. 2020. Available online: https://www.schroders.com/en/insights/economics/how-sustainability-can-make-a-product-stand-out/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Somers, C.; Kohn, R. How Sustainable Are “Fast Fashion” Businesses? Schroders Economic Insights. 2021. Available online: https://www.schroders.com/en/us/wealth-management/insights/strategy-and-economics/how-sustainable-are-fast-fashion-businesses/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Brown-West, B. 2 Keys to the Future of Sustainable Fashion. EDF + Business Insights. 2021. Available online: https://business.edf.org/insights/2-keys-to-the-future-of-sustainable-fashion/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Martuscello, J. The Power of Anticipation and its Influence in Consumer Behavior. The Insights Association. 2018. Available online: https://www.insightsassociation.org/article/power-anticipation-and-its-influence-consumer-behavior (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Busch, L. Individual choice and social values: Choice in the agrifood sector. J. Consum. Cult. 2016, 16, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessz, M.; Dubuisson-Quellier, S.; Gojard, S.; Barrey, S. How consumption prescriptions affect food practices: Assessing the roles of household resources and life-course events. J. Consum. Cult. 2016, 16, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, F. Why Do Consumers Make Green Purchase Decisions? Insights from a Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, Q.; Carmon, Z.; Wertenbroch, K.; Crum, A.; Frank, D.; Goldstein, W.; Huber, J.; van Boven, L.; Weber, B.; Yang, H. Consumer Choice and Autonomy in the Age of Artificial Intelligence and Big Data. Cust. Needs Solut. 2018, 5, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bault, N.; Rusconi, E. The Art of Influencing Consumer Choices: A Reflection on Recent Advances in Decision Neuroscience. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, L.; McCloy, R.; Butler, L.; Vogt, J. Motivational and Affective Factors Underlying Consumer Dropout and Transactional Success in eCommerce: An Overview. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Defense Fund. The Roadmap to Sustainable E-commerce. How the World’s Biggest e-Commerce Retailers Can Use Their Influence to Benefit the Environment and Their Bottom. EDF + Business. 2020, p. 1. Available online: https://business.edf.org/files/EDF018_Playbook_fnl_singlepg.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Kronthal-Sacco, R.; Levin, R. Resuming the US Sustainability Agenda, Information Resources Inc. (IRi). and NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business. 30 September 2021. Available online: https://www.iriworldwide.com/IRI/media/Library/IRI-and-NYU-Resuming-the-Sustainability-Agenda-9-30-21.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Hiatt, E.; The Business Case for Sustainability. The Business Case for Sustainability. Q&A with NYU STERN Center for Sustainable Business. RILA Blog-Retail Industry Leaders Association. 20 April 2021. Available online: https://www.rila.org/blog/2021/04/the-business-case-for-sustainability (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Hiatt, E. Revisiting Retail Sustainability Goals during COVID-19. RILA Blog-Retail Industry Leaders Association. 28 May 2021. Available online: https://www.rila.org/blog/2020/05/revisiting-retail-sustainability-goals-covid19 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Rifkin, S.; Raman, R.; Danielsen, K. The Business Case for Circularity at Reformation. NYU Stern CSB. 2021. Available online: https://www.stern.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/assets/documents/Reformation%20Case%206%3A8%3A21.docx.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Gatzer, S.; Roos, D. The Path Forward for Sustainability in European Grocery Retail. McKinsey & Company Retail Insights. 2021, pp. 1–6. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-path-forward-for-sustainability-in-european-grocery-retail (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Alldredge, K.; Grimmelt, A. Understanding the ever-evolving, always-surprising consumer. McKinsey & Company Insights on Consumer Packaged Goods. 2021, pp. 1, 4–7. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/understanding-the-ever-evolving-always-surprising-consumer? (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Ratcliffe, J.; Stubbs, M. Urban Planning and Real Estate Development; UCL Press Ltd., University College: London, UK, 1996; p. 541. [Google Scholar]

- Accenture. Retail with Purpose Powering Future Growth. Accenture. 2018, pp. 2, 3, 10. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/t20180214T162703Z__w__/us-en/_acnmedia/Accenture/Conversion-Assets/DotCom/Documents/Global/PDF/Dualpub_26/Accenture-Retail-with-Purpose.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Ancketill, K. The Underlying Values, Behaviors, and Needs Driving Purposeful Retail. The DO School Blog. 2 May 2019. Available online: https://thedoschool.com/blog/2019/05/02/the-underlying-values-behaviors-and-needs-driving-purposeful-retail-by-kate-ancketill/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- NielsenIQ. Unlock the Purpose-Driven Grocery Consumer Mindset, Nielsen Education. 11 August 2021. Available online: https://nielseniq.com/global/en/insights/education/2021/unlock-the-purpose-driven-grocery-consumer-mindset/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Cluster, B.; Cooper, D. Purposeful Shopping Can Be a Question Mark for CPGs Is Data Transparency an Answer? The Consumer Goods Forum Blog. 19 November 2021. Available online: https://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/blog/purposeful-shopping-can-be-a-question-mark-for-cpgs-is-data-transparency-an-answer/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Gatzer, S.; Magnin, C. Prioritizing Sustainability in the Consumer Sector. McKinsey & Company Retail Insights, Podcast. 2021, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/prioritizing-sustainability-in-the-consumer-sector (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- The European Financial Review. Sustainability, International Expansion and Tech Adoption Key Priorities for UK CFOs and CEOs Today. The European Financial Review. 7 September 2021. Available online: https://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/sustainability-international-expansion-and-tech-adoption-key-priorities-for-uk-cfos-and-ceos-today/ (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Deloitte, U.K. Sustainability & Consumer Behaviour. 2021. Consumer-business Articles Sustainable-consumer Deloitte UK. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/consumer-business/articles/sustainable-consumer.html (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Dunbar, A. Five Questions for Business Leaders in Search of Next-Level Data Analytics. The European Financial Review. 2 September 2021. Available online: https://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/five-questions-for-business-leaders-in-search-of-next-level-data-analytics/ (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Van Doorn, J.; Risselada, H.; Verhoef, P.C. Does sustainability sell? The impact of sustainability claims on the success of national brands’ new product introductions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 137, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S. Sustainability through the Lens of Environmental Sociology: An Introduction. Sustainability 2017, 9, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinn, R. Sustainability Is a Customer Experience Issue. Continuum Innovation Blog. 25 February 2016. Available online: https://www.continuuminnovation.com/zh-CN/how-we-think/blog/sustainability-is-a-customer-experience-issue (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- McNamee, K.; Fernandez, J. 3 Surprising Ways People Prioritize Sustainability in the Wake of the Pandemic, Think with Google, Consumer Insights. November 2021. Available online: https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/intl/en-ca/consumer-insights/consumer-trends/consumer-sustainability-trends/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Ask, J. The Next Step In Your Brand’s Digital Journey: Anticipatory Digital Experiences (And How To Deliver Them). Forrester Blog. 9 April. Available online: https://go.forrester.com/blogs/the-next-step-in-your-brands-digital-journey-anticipatory-digital-experiences-and-how-to-deliver-them/ (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Warner, R.; Berdak, O.; Sjoblom, S.; Hartig, K. The Forrester Wave™: Cross-Channel Campaign Management (Independent Platforms), Q3 2021. Forrester Report. Available online: https://reprints2.forrester.com/#/assets/2/2150/RES176069/report (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Hart, R.; McQuivey, J.; Giron, F.; Barnes, M. The Dawn Of Anticipatory CX. Forrester Report. 2016. Available online: https://www.forrester.com/report/The+Dawn+Of+Anticipatory+CX/RES134741 (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Hart, R. Welcome to the Dawn of Anticipatory CX. LinkedIn Pulse. 2016. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/welcome-dawn-anticipatory-cx-ryan-hart (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Alchemer. Exploring Data-Driven Customer Science in The Context of Great Customer Experience. Alchemer Blog. 29 August 2017. Available online: https://www.alchemer.com/resources/blog/data-driven-customer-science-and-great-customer-experience/ (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Kroner, E.; Field, D.; Delgado, T. Why Customer Experience is Worth It. Alchemer, Surveygizmo. 2017. Available online: https://www.alchemer.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/surveygizmo-why-customer-experience-is-worth-it-webinar-2017-1.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Van Belleghem, S. How Customer Experience is becoming Customer Science. Steven Van Belleghem Blog. 15 November 2018. Available online: https://www.stevenvanbelleghem.com/blog/how-customer-experience-is-becoming-customer-science/ (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Todesco, F. The Three Ingredients of Customer Science. Knowledge Bocconi. 2021. Available online: https://www.knowledge.unibocconi.eu/notizia.php?idArt=22736 (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- EPAM. Consumers Unmasked. EPAM Continuum, Report, Stage 2, Winter 2021. December 2021, pp. 1, 4–5, 7, 52. Available online: https://www.epam.com/consumers-unmasked-2 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- United Nations Division for Sustainable Development. Consumer Protection and Sustainable Consumption: New Guidelines for the Global Consumer, Background Paper for the United Nations Inter-Regional Expert Group Meeting on Consumer Protection and Sustainable Consumption, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 28–30 January 1998. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/sdissues/consumption/cppgoph4.htm (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Jansson-Boyd, C.V. The Global Consumer. American Psychological Association (APA). 10 September 2020. Available online: https://www.apa.org/international/global-insights/global-consumer (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Purcarea, T. Expo Milano 2015, TUTTOFOOD 2015, and SHOP 2015. Rom. Distrib. Comm. Mag. 2015, 6, 18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen. The Sustainability Imperative. New Insights on Consumer Expectations. October 2015, pp. 3–17. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/04/Global20Sustainability20Report_October202015.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Steenkamp, J.-M.E.M. Global Versus Local Consumer Culture: Theory, Measurement, and Future Research Directions. J. Int. Mark. 2019, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, T.; Hoefel, F. Gen Z and the Latin American Consumer Today. McKinsey & Company, Consumer Packaged Goods and Retail Practices. December 2020, pp. 1–7. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/gen-z-and-the-latin-american-consumer-today (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Smith, T.R.; Yamakawa, N. Asia’s Generation Z Comes of Age, McKinsey’s Sydney Office, and Tokyo Office. 17 March 2020, pp. 1–3. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/asias-generation-z-comes-of-age (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Ernst & Young. The CEO Imperative: Make Sustainability Accessible to the Consumer. The EY Future Consumer Index. June 2021, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_gl/news/2021/06/ey-future-consumer-index-68-of-global-consumers-expect-companies-to-solve-sustainability-issues (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Business Wire. The Brand vs. Product Paradox: New Research from Allison+Partners Shows that In-House Tech PR Pros Struggle with Storytelling Priorities. Business Wire News. 14 December 2021. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20211213006068/en/The-Brand-vs.-Product-Paradox-New-Research-from-AllisonPartners-Shows-that-In-House-Tech-PR-Pros-Struggle-with-Storytelling-Priorities (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Straight, B. Shifting Behaviors: Hybrid Shopping, Purpose-Driven Consumers Change Retail’s Outlook, FreightWaves. 13 January 2022. Available online: https://www.freightwaves.com/news/shifting-behaviors-hybrid-shopping-purpose-driven-consumers-change-retails-outlook (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Purcarea, T. A Book to Understand Modern China, Romanian Distribution Committee Magazine. 30 November 2015. Available online: https://www.distribution-magazine.eu/?s=A+book+to+understand+Modern+China (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Huang, X.; Kuijpers, D.; Li, L.; Sha, S.; Chenan, X. How Chinese Consumers Are Changing Shopping Habits in Response to COVID-19; McKinsey’s Hong Kong Office, Singapore Office and Shanghai Office. 6 May 2020, pp. 1–2, 10–12. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/asia-pacific/how-chinese-consumers-are-changing-shopping-habits-in-response-to-covid-19 (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Poh, F.; Zipser, D.; Toriello, M. The Chinese Consumer: Resilient and Confident; McKinsey’s Shanghai Office, Shenzhen Office, and New York Office. September 2020, pp. 1–2. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/the-chinese-consumer-resilient-and-confident (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- McKinsey & Company. Understanding Chinese Consumers: Growth Engine of the World. China Consumer Report 2021, Special Edition. November 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/china/china%20still%20the%20worlds%20growth%20engine%20after%20covid%2019/mckinsey%20china%20consumer%20report%202021.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Holzmann, A.; Grünberg, N. “Greening” China: An Analysis of Beijing’s Sustainable Development Strategies, Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) Report. China Monitor. 7 January 2021. Available online: https://merics.org/en/report/greening-china-analysis-beijings-sustainable-development-strategies (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- The Brookings Institution. Global China: Assessing China’s Growing Role in the World. Newsletter. 29 December 2021. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/interactives/global-china/? (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Daxue Consulting. Sustainable Consumption in China: Are Chinese Consumers Ready to Ride the Green Wave? Market Research China. 9 September 2021. Available online: https://daxueconsulting.com/sustainable-consumption-china/ (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- The Silk Initiative. What Does Sustainability Mean to Chinese Consumers? TSI. 21 October 2021. Available online: https://www.thesilkinitiative.com/post/what-does-sustainability-mean-to-chinese-consumers (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- The Silk Initiative. The TSI Navigator™ Compass: Sustainability in China. What Sustainability Means to the Chinese Consumer. TSI. October 2021, pp. 6, 16–24. Available online: https://b9193735-1610-4074-923d-3832f64c744f.filesusr.com/ugd/d001e9_45229ce0eaf947fab4a7e599678393cd.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Hagedorn, R. Excess Packaging SURVEY. The Consumer Goods Forum, End-to-End Value Chain. April 2021, pp. 1–4. Available online: https://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/excess-packaging-survey_V6.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Srivastav, P. Stronger Together: Plastics and Packaging Solution Requires Innovative Partnerships. The Consumer Goods Forum Blog. 13 January 2022. Available online: https://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/blog/stronger-together-plastics-packaging-solution-requires-innovative-partnerships/ (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Consumer Goods Forum. CGF China Day 2021. The Consumer Goods Forum Blog. 30 October 2021. Available online: https://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/events/cgf-china-day-2021/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Cristea, M.-A. China, the Seventh Trading Partner of Romania. Will the Coronavirus affect the economy? Business Review. 6 March 2020. Available online: https://business-review.eu/international/china-the-seventh-trading-partner-of-romania-will-the-coronavirus-affect-the-economy-208436 (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Stefan, C. Chinese Retailer Mumuso Opens Its Fourth Mono-Brand Store in Romania, Money Buzz! Europa. 12 February 2021. Available online: https://moneybuzzeuropa.com/chinese-retailer-mumuso-opens-its-fourth-mono-brand-store-in-romania/ (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Brattberg, E.; Feigenbaum, E.A.; Le Corre, P.; Stronsky, P.; De Waal, T. China’s Influence in Southeastern, Central, and Eastern Europe: Vulnerabilities and Resilience in Four Countries. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 13 October 2021. Available online: https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/10/13/china-s-influence-in-southeastern-central-and-eastern-europe-vulnerabilities-and-resilience-in-four-countries-pub-85415 (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Flanders Investment & Trade. E-Commerce Market in Romania. Flanders Investment & Trade Market Survey. December 2020, pp. 1–16. Available online: https://www.flandersinvestmentandtrade.com/export/sites/trade/files/market_studies/E-commerce%20market%20in%20Romania%202020.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- US International Trade Administration. Romania-Country Commercial Guide. 30 September 2021. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/romania-market-overview (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- US International Trade Administration. Distribution and Sales Channels. 1 October 2021. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/romania-distribution-and-sales-channels (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- US International Trade Administration. eCommerce. 1 October 2021. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/romania-ecommerce (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Purcarea, T.; Purcarea, A. Distribution in Romania at the shelf supremacy’s moment of truth: Competition and cooperation. Amfiteatru Econ. 2008, 10, 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- CBRE. How Active is the Romanian Retail Market? Retail Science from CBRE. CBRE Romania Research. 2015. Available online: https://www.cbre.ro/en/research-and-reportsCBRE-Romania_How-Active-Retail-Market.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Tanase, G.C. The Romanian Retail Market Evolution 2015 Analysis. Rom. Distrib. Comm. Mag. 2016, 7, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Consiliul Concurenţei. Raport al Investigaţiei Privind Sectorul Comerţului Electronic-Componenta Referitoare la Strategiile de Marketing. Direcţia Cercetare, Raportor: Florin Opran, Noiembrie 2018. pp. 6, 9, 22, 59, 61, 64–65, 68, 225. Available online: Raport_comel_final-1.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Colliers. COVID-19 Survey: How Does COVID-19 Affect the Retail Market in Romania? Colliers International. 22 April 2020. Available online: https://www.colliers.com/en-ro/research/colliers-romania-covid-19-retail-survey-2020 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- USDA. Romania: COVID-19 Transforms Romanian Retail and Food Service Sectors, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, Attaché Reports (GAIN). 29 July 2020. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/romania-covid-19-transforms-romanian-retail-and-food-service-sectors (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Deloitte Romania. Romanian Consumer Trends. Deloitte. 2020. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/ro/en/pages/about-deloitte/consumer/romanian-consumer-trends.html (accessed on 30 November 2021).

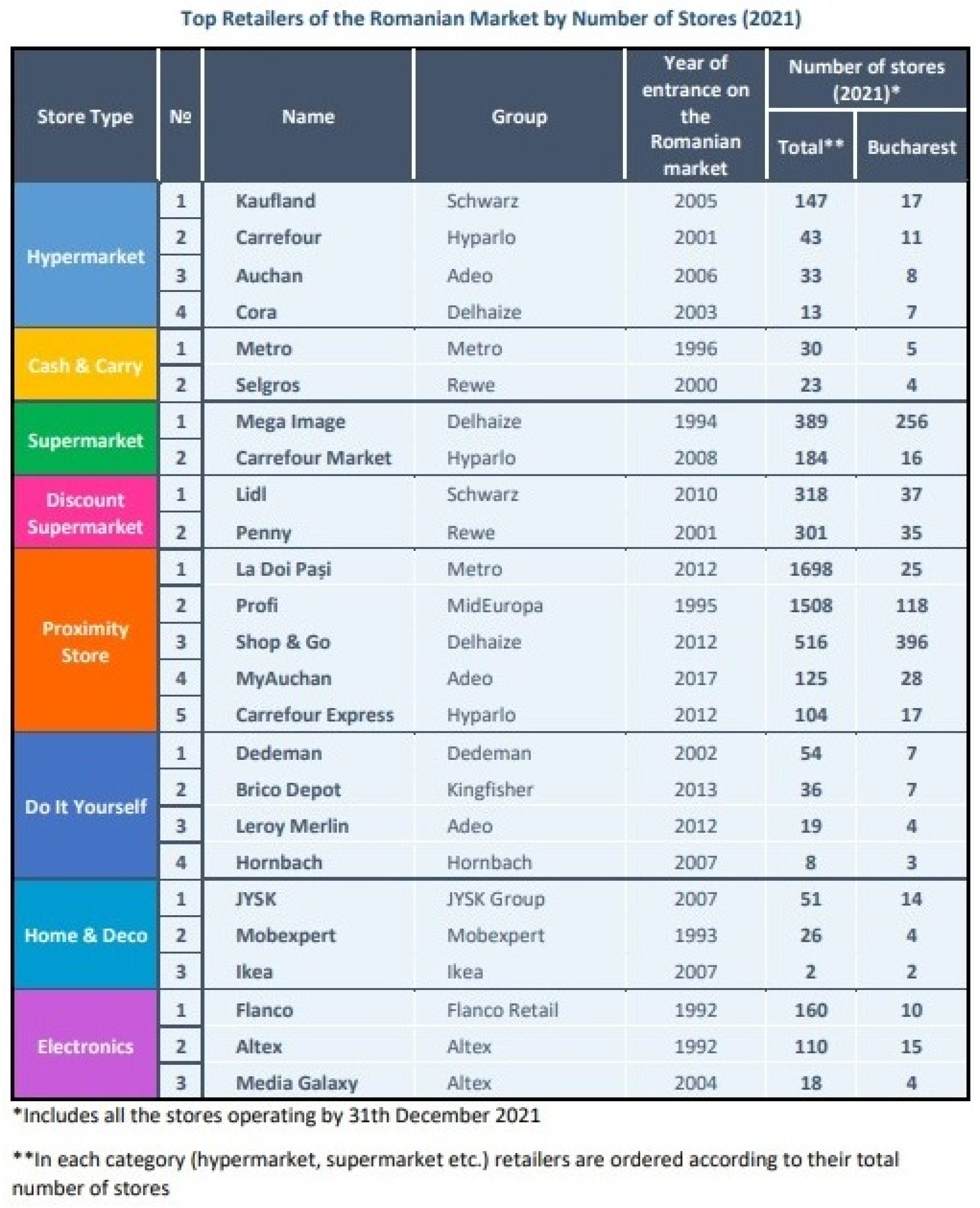

- Colliers. ExCEEding Borders. Alive & Kicking. CEE-16 Retail. December 2021, p. 30. Available online: https://f.datasrvr.com/fr1/421/64993/Colliers_ExCEEding_Borders_Retail_2021.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Sava, J.A. Major Retail Chains for Food Shopping in Romania 2020, by Revenue. Statista. 14 July 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1114791/romania-retail-chains-for-food-shopping-by-annual-turnover/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Sava, J.A. Number of Retail Chains in Romania 2021, by Sector. Statista. 11 June 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/642260/retail-chains-number-by-sector-romania/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Romanian Distribution Committee. Top Retailers of the Romanian Market by Number of Stores (2021). Romanian Distribution Committee News. 12 January 2022. Available online: https://www.crd-aida.ro/2022/01/top-retailers-of-the-romanian-market-by-number-of-stores-2021/ (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Radu, A. Estimare GPeC: Comerțul online românesc crește cu 15% față de 2020. GPeC Blog. 14 October 2021. Available online: https://www.gpec.ro/blog/estimare-gpec-comertul-online-romanesc-creste-cu-15-fata-de-2020 (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- European Commission. Towards a Greener Retail Sector, European Commission (DG ENV) 070307/2008/500355/G4, Final Report, February, In Association with GHK, Ecologic, TME and Ekopolitika. 2009, p. 3. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/archives/eussd/pdf/report_green_retail.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Coca, V.; Dobrea, M.; Vasiliu, C. Towards a sustainable development of retailing in Romania. Amfiteatru Econ. 2013, 15, 596–597. [Google Scholar]

- Dabija, D.C.; Pop, C.M. Green marketing—Factor of Competitiveness in Retailing. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2013, 12, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, T.; Bostan, I.; Manolică, A.; Mitrica, I. Profile of Green Consumers in Romania in Light of Sustainability Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6394–6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Wildlife Fund Romania. Supermarkets in Romania Improve Their Sustainability Record. WWF News. 2016. Available online: https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?259272/Supermarkets%2Din%2DRomania%2Dimprove%2Dsustainability%2Drecord (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Dabija, D.C.; Bejan, B.M.; Grant, D.B. The impact of consumer green behaviour on green loyalty among retail formats: A Romanian case study. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2018, 26, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dabija, D.C.; Bejan, B.M.; Dinu, V. How Sustainability Oriented is Generation Z in Retail? A Literature Review. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2019, 18, 140–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dabija, D.C.; Bejan, B.M.; Puscas, C. A Qualitative Approach to the Sustainable Orientation of Generation Z in Retail: The Case of Romania. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufland Romania. Our Actions Do the Talking: Leading Romanian Sustainability. 2017 Corporate Sustainability Report Kaufland Romania. 2017, pp. 5, 6, 14, 72. Available online: https://storage.googleapis.com/edfbiz_website/Products%20Packaging%20Waste/EDF018_Playbook_fnl_singlepg.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Cristea, M. Felician Cardos, Environmental Manager at Carrefour Romania. Business Review, GreenRestart Interview. 2020. Available online: https://business-review.eu/greenrestart/greenrestart-interview-series/geenrestart-interview-felician-cardos-environmental-manager-at-carrefour-romania-214412 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Cristea, M. Carrefour Romania Launches Act For Good—The program That Helps You Do Good While Shopping. Business Review, Retail. 2021. Available online: https://business-review.eu/business/retail/carrefour-romania-launches-act-for-good-the-program-that-helps-you-do-good-while-shopping-216686 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Wagner, F. Scrisoare UN Global Compact 2021. Lidl Romania. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/active/449538 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Lidl Romania. It’s Our Responsibility for New Generations Deserving a Better Future. Sustainability Report Lidl Romania. 2021, p. 3. Available online: https://ungc-production.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/attachments/cop_2021/495002/original/raport%20FY2019%20EN.pdf?1616581983 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Tudor, A. Auchan România Lansează Raportul de Sustenabilitate 2020 și Prezintă Performanța non-Financiară a Companiei. Retail & FMCG. 29 November 2021. Available online: https://www.retail-fmcg.ro/retail/auchan-romania-raport-sustenabilitate-2020.html (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Tudor, A. Romanian FMCG Retail—The Most Important News from November 2021. Retail & FMCG. 3 December 2021. Available online: https://www.retail-fmcg.ro/english/news-from-romania/romanian-fmcg-retail-news-november-2021.html (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Haydam, N.; Purcarea, T.; Edu, T.; Negricea, I.C. Explaining Satisfaction at a Foreign Tourism Destination—An Intra-Generational Approach. Evidence within Generation Y from South Africa and Romania. Amfiteatru Econ. 2017, 19, 528–542. [Google Scholar]

- Brandtner, P.; Darbanian, F.; Falatouri, T.; Udokwu, C. Impact of COVID-19 on the Customer End of Retail Supply Chains: A Big Data Analysis of Consumer Satisfaction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picón, A.; Castro, I.; Roldán, J.L. The relationship between satisfaction and loyalty: A mediator analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudet, J.; Huang, J.; Rothschild, P.; von Difloe, R. Preparing for Loyalty’s next Frontier: Ecosystems. McKinsey & Company, Marketing & Sales. March 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/preparing-for-loyaltys-next-frontier-ecosystems (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R. Test Theory: A Unified Treatment; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse, B.; Jackson, P.H. Lower bounds for the reliability of the total score on a test composed of non-homogeneous items. II: A search procedure to locate the greatest lower bound. Psychometrika 1977, 42, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moltner, A.; Revelle, W. Find the Greatest Lower Bound to Reliability. The Personality Project. 2015. Available online: http://personality-proj-ect.org/r/psych/help/glb.algebraic (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Cho, E.; Kim, S. Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha: Well Known but Poorly Understood. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 11.0 Update, 4th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rizopoulos, D. ltm: An R Package for Latent Variable Modeling and Item Response Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2006, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rizopoulos, D. Latent Trait Models under IRT Version 1.1-1. 17 April 2018. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ltm/ltm.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, L.S.; Glenn CGamst, G.C.; Guarino, A.J. Applied Multivariate Research: Design and Interpretation, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Romania | Younger Than 18 | 18–25 Years Old | 26–35 Years Old | 36–45 Years Old | 46–55 Years Old | 56–65 Years Old | 66 Years or Older | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 10 | 135 | 114 | 149 | 54 | 28 | 3 | 493 |

| Female | 8 | 143 | 127 | 153 | 51 | 33 | 7 | 522 |

| Total | 18 | 278 | 241 | 302 | 105 | 61 | 10 | 1015 |

| Consumers’ Willingness to Change Their Shopping Habits to Reduce Environmental Impact (W) | W1 | When choosing a brand, are you looking for specific attributes which are important to you? |

| W2 | Would you rather select brands based on how well they align with your personal values, such as sustainability, changing your behavior accordingly (purpose-driven consumers) or based on price and convenience (value-driven consumers)? | |

| W3 | Are you shopping in the so-called (by Google and Forrester, 2015) micro-moments (shopping while doing something else, turning to a device like a smartphone, making decisions and shaping preferences)? | |

| W4 | Are you willing to change your shopping habits to reduce environmental impact? | |

| W5 | Do you think that sustainability is important for consumers in Romania, and that there are lifestyle changes to address this challenge? | |

| W6 | Do you think there has been a change in your attitude as a consumer in direct and sustainable response to a newly appreciated risk? | |

| W7 | Do you think that there is a gap between your purchasing attitude (encouraged by the above-mentioned awareness) and your current buying behavior as a responsible consumer (considering the different individual, social and situational factors influencing your decision process)? | |

| Retailers’ Increased Concentration on Responsibly Answering to Sustainability as a Personal Value of Consumers Changing Their Behavior (R) | R1 | Do you agree with the Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP, adopted by the European Commission in March 2020, as one of the main building blocks of the European Green Deal, Europe’s new agenda for sustainable growth), which ensures the adoption of the new sustainable model by businesses, consumers, entrepreneurs, and public authorities? |

| R2 | Do you agree with the European Green Deal (EGD) for the European Union (EU) proposed for the EU and its citizens by the European Commission (Communication and Roadmap on the European Green Deal, committing to climate neutrality by 2050) in December 2019 (before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic) and aimed at increasing the efficient use of resources by moving to a clean and circular economy, stopping climate change, and reducing pollution? | |

| R3 | Do you agree with the opinion of the European Commission that the European Green Deal is also seen as a lifeline from the COVID-19 pandemic? | |

| R4 | Do you agree that the European Green Deal should also take into account the “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (which includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals/SDGs) adopted by the United Nations (UN) in 2015 as a global plan for sustainability, so as to meet the needs of current generations without compromising those of future generations? | |

| R5 | Do you agree with Japan’s initiative known as “Society 5.0” in which smart technologies are to support sustainable development? “Society 5.0” (next level after the current Information Society, a policy for a data-driven society promoted by the digital revolution) has been officially defined as “A human-centered society that balances economic advancement with the resolution of social problems by a system that highly integrates cyberspace (AI, Big Data) and physical space”? | |

| R6 | Did you know that consumer products are the largest source of environmental impact in the modern world, contributing to climate change, destroying widespread natural resources and ecosystems, exposing people to hazardous chemicals, and filling the ocean and landfills around the globe? | |

| Retailers’ Sustainability Agenda, Including by Fulfilling Consumers’ Sustainability Demands with New Products and Processes (S) | S1 | Are you as a shopper expecting brands to offer products and services both with eco-friendliness in mind and for the right price? |

| S2 | Did you notice any preoccupations of the supermarket chain (or of some supermarket chains) which can be considered related to the European Green Deal? | |

| S3 | Do you think that there is a need for improved promotion with regard to the three pillars of sustainable development (economic, social, and environmental)? | |

| S4 | If you will choose a brand with sustainability in mind, will you do research before purchasing it, wanting assurances? | |

| S5 | Do you think that the supermarket chain generates your awareness of consequences of sustainable shopping through better communication about sustainability (such as rational advertising with regard to its sustainability efforts or the use of emotions in motivating consumers’ shift towards sustainable behavior and reward programs mixed with communication in social media to increase green sales) and its practice of Corporate Social Responsibility (thanks to an assortment of sustainable products with a socially and environmentally compatible supply chain)? | |

| S6 | Do you think that the supermarket chain is increasing transparency in its supply chain by integrating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) requirements into procurement policies? | |

| Retailers’ Digital Transformation to Aid Consumers to Adopt More Sustainable Lifestyles and to Make Informed Choices in the Omnichannel World (D) | D1 | Was the source of information for what you noticed more from social networks and less from classic advertising spots? |

| D2 | Was access to the source of information (for those 816 respondents, from 1015, who noticed preoccupations of the supermarket chain related to the European Green Deal) provided by marketing messages influencing the purchase received on mobile devices? | |

| D3 | Do you think that the COVID-19 pandemic has changed fundamentally the supermarket chain’s way of engaging consumers by offering so-called “phygital” experiences? | |

| D4 | Do you think that the supermarket chain takes into account consumers’ evolving perceptions of sustainable-product efficacy (in accordance with their environmental values) and is struggling to stimulate their perceptions of the company as investing in sustainability, including in partnerships with suppliers developing sustainable products (by making technology investments)? | |

| D5 | Do you think that the supermarket chain is improving its approach with regard to e-commerce platforms, home delivery services, and take-back systems (as key value factors), in terms of the efficiency, safety, and sustainability of supply chain management, distribution systems, and the use and disposal of packaging? | |

| D6 | Do you think that, as an expression of its responsibility for the environmental and health impact of their products and operations, the supermarket chain can help shoppers make sustainable choices by using their online marketplace to provide more in-depth education with regard to the everyday products’ impact on the environment and shoppers’ health? | |

| D7 | Do you think that the supermarket chain could use an e-commerce platform to attract and engage the conscious consumer who wants to know more about the impact of a product on the environment and health (in addition to the recourse by the supermarket chain to the use of e-mail, social networks, online promotions, etc.)? | |

| D8 | Do you think that the supermarket chain could use the e-commerce channel to provide new opportunities for circular consumption (for new business models which extend the product life cycle, such as renting, repurchasing, and reselling)? | |

| D9 | Do you think that the supermarket chain has improved the customer-oriented systems (such as websites or applications) so that its customers are stimulated to adopt more sustainable lifestyles and make informed choices? | |

| D10 | Coming back to the channel of e-commerce used by the supermarket chain, do you think that e-commerce can play a role in driving the green economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic while addressing climate change? | |

| Retailers’ Need to Translate Consumers’ Uncertainty Into Trust, Identifying Risks Associated with Disruptive Technologies and Making Them Less Severe (T) | T1 | As a consumer, could you say that you perceive a certain inability to predict to what extent the supermarket chain can help shoppers make sustainable choices or strengthen their sustainable consumption routines? |

| T2 | As a consumer, would you say that, perceiving the above-mentioned inability, you take the risk of not accurately predicting the outcome of investments made by the supermarket chain in sustainability, including in partnerships with suppliers who develop sustainable products (by investing in technology)? | |

| T3 | Do you think that the supermarket chain could take a strategic decision to synchronize their innovation activity (through investments in sustainability, new technologies, digital transformation, etc.) in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic so that, within the competitive battle on the relevant market with other supermarket chains (which reduce investments of this kind), it can obtain the first-mover advantage? | |

| T4 | Within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the supermarket chain faces continual change in the direction needed to deal with the complex situation. Do you think that in its management of uncertainty the supermarket chain you frequent has the capability to act for improvements in the necessary directions (costs improvement, performance, confidence in achieving goals)? | |

| T5 | As a consumer, would you say that you are averse to uncertainty with regard to the result of investments in sustainability made by the supermarket chain (prior experiences or beliefs influencing your interpretation of forecasts and predictions)? | |

| T6 | Assuming that you are averse to uncertainty with regard to the result of investments in sustainability made by the supermarket chain, would you also say that, in the case of such uncertainty, you feel anxious? | |

| T7 | In order to maintain relevance and stay competitive, the supermarket chain, like any business today, needs to consider the digital readiness of its workforce to transition into digitized workflows that are enabled by software and technology. In your opinion, is the supermarket chain facing this challenge? | |

| T8 | It was demonstrated that, within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, digitization is crucial to a company’s survival. Do you think that the supermarket chain has identified ways that digital transformation can aid its customers to adopt more sustainable lifestyles and to make informed choices? | |

| T9 | Recent research highlights companies’ need to translate uncertainty into confidence, ensuring differentiation on this basis, identifying risks and making them less severe or painful (including those associated with emerging technologies, and taking advantage of these technologies to optimize their risk function), and turning digital risks into competitive advantage to activate digital trust. Do you think that the supermarket chain is building a digital framework which can deliver sustainable value from risk and transform consumers into digitally trusted partners? |

| MEAN | SD | MEAN | SD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | W1 | 3.759606 | 1.477425 | D | D1 | 3.568627 | 1.716809 |

| W2 | 2.519212 | 1.615194 | D2 | 2.746798 | 1.513231 | ||

| W3 | 3.809852 | 1.503547 | D3 | 4.210837 | 1.431155 | ||

| W4 | 3.928079 | 1.510564 | D4 | 3.929064 | 1.596623 | ||

| W5 | 3.91133 | 1.511305 | D5 | 4.212808 | 1.323447 | ||

| W6 | 4.131034 | 1.370142 | D6 | 4.223645 | 1.394633 | ||

| W7 | 3.827586 | 1.558468 | D7 | 4.203941 | 1.301942 | ||

| MEAN | SD | D8 | 4.208867 | 1.363703 | |||

| R | R1 | 3.358621 | 1.71588 | D9 | 3.846305 | 1.712589 | |

| R2 | 3.364532 | 1.703669 | D10 | 3.835468 | 1.610959 | ||

| R4 | 3.325123 | 1.690765 | MEAN | SD | |||

| R5 | 2.881773 | 1.721145 | T | T1 | 3.836453 | 1.740812 | |

| R6 | 3.661084 | 1.777964 | T2 | 3.850246 | 1.607195 | ||

| MEAN | SD | T3 | 3.844335 | 1.703751 | |||

| S | S1 | 4.60197 | 0.882213 | T4 | 3.854187 | 1.661853 | |

| S2 | 4.212808 | 1.365261 | T5 | 3.849261 | 1.69054 | ||

| S3 | 4.072906 | 1.510843 | T6 | 3.833498 | 1.59414 | ||

| S4 | 3.660099 | 1.745587 | T7 | 3.84532 | 1.685509 | ||

| S5 | 3.84532 | 1.685509 | T8 | 3.847291 | 1.626133 | ||

| S6 | 3.848276 | 1.647613 | T9 | 3.862069 | 1.586024 | ||

| Scale | α Cronbach | Number of Items | |

|---|---|---|---|

| W. Consumers’ willingness to change their shopping habits to reduce environmental impact | 1–5 | 0.682 | 7 |

| R. Retailers’ increased concentration on responsibly answering to sustainability as a personal value of consumers changing their behavior | 1–5 | 0.785 | 6 |

| S. Retailers’ sustainability agenda, including by fulfilling consumers’ sustainability demands with new products and processes | 1–5 | 0.763 | 6 |

| D. Retailers’ digital transformation to aid consumers to adopt more sustainable lifestyles and to make informed choices in the omnichannel world | 1–5 | 0.824 | 10 |

| T. Retailers’ need to translate consumers’ uncertainty into trust, identifying risks associated with disruptive technologies and making them less severe | 1–5 | 0.904 | 9 |

| Hypothesis | Relation | β | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | R←W | 0.261 | 0.000 | Valid model |

| H2 | R←S | 0.164 | 0.000 | Valid model |

| H3 | D←S | 0.345 | 0.012 | Valid model |

| H4 | D←R | 0.496 | 0.003 | Valid model |

| H5 | T←D | 0.332 | 0.163 | Risk of 16% |

| H6 | T←W | 0.290 | 0.038 | Valid model |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Purcărea, T.; Ioan-Franc, V.; Ionescu, Ş.-A.; Purcărea, I.M.; Purcărea, V.L.; Purcărea, I.; Mateescu-Soare, M.C.; Platon, O.-E.; Orzan, A.-O. Major Shifts in Sustainable Consumer Behavior in Romania and Retailers’ Priorities in Agilely Adapting to It. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031627

Purcărea T, Ioan-Franc V, Ionescu Ş-A, Purcărea IM, Purcărea VL, Purcărea I, Mateescu-Soare MC, Platon O-E, Orzan A-O. Major Shifts in Sustainable Consumer Behavior in Romania and Retailers’ Priorities in Agilely Adapting to It. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031627

Chicago/Turabian StylePurcărea, Theodor, Valeriu Ioan-Franc, Ştefan-Alexandru Ionescu, Ioan Matei Purcărea, Victor Lorin Purcărea, Irina Purcărea, Maria Cristina Mateescu-Soare, Otilia-Elena Platon, and Anca-Olguța Orzan. 2022. "Major Shifts in Sustainable Consumer Behavior in Romania and Retailers’ Priorities in Agilely Adapting to It" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031627

APA StylePurcărea, T., Ioan-Franc, V., Ionescu, Ş.-A., Purcărea, I. M., Purcărea, V. L., Purcărea, I., Mateescu-Soare, M. C., Platon, O.-E., & Orzan, A.-O. (2022). Major Shifts in Sustainable Consumer Behavior in Romania and Retailers’ Priorities in Agilely Adapting to It. Sustainability, 14(3), 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031627