Abstract

An increasing percentage of products in multichannel retail are being returned, yet many retailers and manufacturers are not aware of the importance and scale of this issue. Similarly, the literature on online returns is limited. Returns processes can be very complicated, contain many manual steps that have several variations, unclear decision-making rules and, at the handling stage, often involve low-wage third-party employees guided by patchy IT systems. This article maps the complexity of product returns processes, highlights challenges and identifies opportunities for improvement, thereby contributing to a deeper understanding of the emerging field of product returns research. It also concludes that it is essential for returns to be made a strategic priority at the senior management level, implementing a Lean approach to returns systems. The research was based on 4 case studies, 17 structured interviews and 3 retail community workshops, all with British and other Western European retailers. Through triangulation of individual data, a generic process map for retail returns was created and implications for sustainability, loss prevention and profit optimisation are examined.

1. Introduction

Many retailers strive to build a multichannel presence as eCommerce has been growing strongly—even more so since the beginning of the pandemic. This means integrating their virtual and physical shopping channels, and first-class customer service is often considered to be essential for driving sales. Hence, many retailers offer free delivery and several ways of returning items—including return to store of items sold online. Delivery fees affect the attitudes and behaviours of customers [1], and the same applies to costs of returns [2]. With a ‘free’ returns service to customers, which has led to a higher than anticipated number of returns, many businesses are unaware of the true costs of returns to the business and the extent to which this offering is prone to abuse, leading to retail loss [3,4,5]. Many of the issues with returns have been exacerbated in 2020–21 due to the explosion of eCommerce due to the global health crisis. Generally, current returns systems are front-end driven and follow the “push” principle [6]. Instead, retailers should adopt a “pull” strategy when designing their returns systems, as discussed in Section 2 and Section 5. Product returns systems are complex and multidisciplinary in nature and require strategic planning; they cannot be left for loss prevention managers to deal with. This formerly simple role is now typically called ‘asset profit and protection’ or similar, and its effective execution requires the right cross-functional team approach run by senior management [7]. Despite the recent increase in academic literature on product returns, there is still a lack of academic studies to support the implementation of better returns systems, especially when it comes to aspects of strategic management.

This project—described in detail in [8]—was conducted for an association of European retailers and manufacturers. They were keen to understand the scale and true costs of product returns, the challenges and vulnerabilities in nowadays’ returns systems, best practices and opportunities for improvement, including ways to become more sustainable in economic and ecologic aspects. The project included an extensive study of 100 UK and Western European retailers’ eCommerce returns policies; a review of other relevant projects; four detailed case studies with large retailers in the UK; as well as interviews with a further 17 retailers in the UK and Western/Central Europe.

The aims of this article are to propose a mapping framework for product returns processes, grounded in process management, sustainability and customer experience; to diagnose the retail challenges and opportunities associated with product returns processes; and to address the current vacuum at the strategic management level. Methodological inspiration is taken from [9], who applied service mapping in the context of evaluating and improving service quality, suggesting that it could “result in a written ‘map’ showing stages and subprocesses in the delivery of a service or a graphic map that has the advantage of visually illustrating the flow of the service process”. In this article, we do both, as detailed descriptions, as well as a graphic overview, are required to achieve a full understanding of the product returns process complexity.

2. Related Work: Product Returns and Reverse Supply Chains

Literature on product returns in a multichannel or omnichannel environment is still relatively scarce and is spread over a number of disciplines. Although the terms are often used interchangeably, multichannel retail usually refers to the use of various sales channels, such as stores, online, mobile/tablet, telephone and catalogue/mail order. Omnichannel refers to the retailer offering a seamless experience across the various channels; e.g., a consumer can start an order on the tablet and continue on the computer, and in case of a problem ring the hotline who will then seamlessly complete the order over the phone. In this article, we use the term multichannel, as it is currently more prevalent, although omnichannel businesses face the same challenges.)

Whilst some researchers have looked at the strategies that retailers have adopted over the last 20 years to increase online sales and customer satisfaction, others have examined the unintended consequences of increasing online sales in terms of customer behaviours and sustainability. Retailers across all pricing points have adopted very similar policies and practices and experience very similar issues. The main reason is not to lose market share to competitors with online offerings and to increase the number of touch-points with customers, as [10] found in their study of multi- and omnichannel strategies by fashion and apparel retailers.

One indicator of the competitive drive behind multichannel retailing is the push to give customers free delivery and returns via multiple paths, the accepted wisdom being that these are essential to successful online sales [11]. However, lenient return policies incentivise unnecessary ordering and lead to higher return rates, which in turn have consequences for consumer behaviour and for managing the increasingly complex ecological and economical aspects [12]. Examining the reasons for returns frequency for different customer segments, Foscht et al. [13] argued in favour of penalising frequent returners as well as providing better communication channels for consumers to access further information about products sold online. These tactics for increasing sales and managing returns, however, show the extent to which multichannel operations are creating unintended consequences for retailers.

Returns are one such unintended consequence and have become a more pressing issue, moving from a cost of doing business to a more serious erosion of net profit margins [14]. There is a tension between providing good customer service and enforcing returns policies [11,15]. Although the phenomenon of “deliberate and premeditated returns” was identified 20 years ago under the title of “Deshopping—the art of illicit consumption” [16], the problem is growing. This behaviour was linked to the limited financial power of certain population groups, high prices of certain items that are only used a couple of times, as well as to a “risk reduction strategy” for consumers who are not certain whether the product will fit their needs. King et al. [15] concluded that there was a low degree of awareness of this problem amongst fashion retailers, and only very few had adapted their returns policies to limit deshopping behaviour. More recently, the reasons for returns, or de-shopping, have been found to be correlated with emotional dissonance that occurs when purchased products do not meet expectations or when they are later found cheaper/in better quality at another retail site [17]. Cook and Yurchisin [18] found that product returns in the fast fashion sector are often linked to impulse buying, with negative emotions following afterwards. It can be inferred that retailers have now to adapt their systems, policies and practices to fast-changing consumer behaviours, making efficiency and effectiveness in returns more difficult to achieve.

Furthermore, product returns are inherently wasteful in terms of resources; ideally, transportation and processing should be kept minimal, and the value retained in products should be maximised. The circular economy offers approaches for this [14], but retailers still struggle to integrate this into their agendas. Bernon et al. [19] presented a framework for aligning retail reverse logistics with circular economy values, whilst also admitting that there is little appreciation in the industry of how circular concepts can be used or embedded in reverse logistics. One way is to organise better access to secondary markets, where used products or products returned in the imperfect state find new owners. Beh et al. [20] emphasized the importance of secondary markets in fashion retail, which is particularly attractive in the case of high-priced brands sold through discount outlets.

From the literature, it is clear that customer behaviour and environmental concerns are amplified by the rise in multichannel shopping. The problem is exacerbated by several logistical challenges of increased returns from internet and catalogue sales, as opposed to sales from brick-and-mortar stores [21]. In many areas of eCommerce, but particularly when it comes to multichannel environments, product returns processes need further development and streamlining [22]. A serious issue is the incremental nature of changes in e-retailing, with returns processes in e-retailing varying widely across companies and supply chains [23]. There often appears to be no clear strategy as retailers race to provide the same services as their competitors [23]. Multichannel businesses originating from brick-and-mortar retail appear to fare worse than those built on the foundations of catalogue mail-order companies whose underlying processes are better suited for eCommerce [8]. Product returns processes are shaped under institutional factors, including non-market and market pressures, and there is considerable potential to optimise the effectiveness of returns systems [24].

The ineffectiveness of existing systems has been shown by the mismatch of individual purchasing and returns journeys online, despite there being generalisable patterns in behaviours [25]. In service and retail supply chains, the customer is immersed at many stages of the forward and reverse chain. Customers can notice a problem or change their mind early on, and hence reverse flows of information, money and goods may need to be managed throughout the processes. One example is the difficulty in reconciling refunds with returned products; another is Click&Collect orders that customers fail to collect [26]. Another issue, identified in a study [27] on mobile phones being sold back by purchasers, are the less organised reverse supply chains that cast doubt on whether external regulations on discarded electronics are complied with. WEEE needs to be taken back by retailers for recycling (at least in Europe), but the implementation is often dubious.

Returns can be used to boost customer loyalty as well as to increase profits by treating return products as assets and considering the impact on corporate image, as Tibben-Lempke and Rogers [28] recognised early on. They conclude that effective returns management includes avoidance (selling the product in a way that minimises returns), gatekeeping (screening the return request and the returned product) and disposition procedures (what to do with the returned product). Nel and Badenhorst [29] have also looked at the opportunities, creating a conceptual framework for understanding and creating management systems for online returns. Their solutions are broad-brush and require investment in technology; employee training; providing correct information for customers; and customer service. While they provide a conceptual map of the issues involved, their work does not address how to streamline systems and reduce costs. To address these, as well as the organisational complexities of product return processes, companies need cross-functional teams and input from interdisciplinary research teams [30] in [31].

Following these points, there appears to be no academic literature on the notion of lean returns management, although there is a small literature on lean management in forward sales in retail. Retail markets are characterised as having fierce competition, shorter product life cycles, longer product development time and high sensitivity of demand [32]. With Lean thinking, efficiency can be maximised whilst any waste is identified and eliminated. The application of Lean concepts in retail dates back to the 1990s, with Walmart, Tesco and IKEA being pioneers [32]. With an efficient consumer response strategy, manufacturers and retailers aim to optimise flows of products and information throughout the value chain, starting with the point of sale and collecting detailed data on customer demand [32]. Similar results were found when investigating the lean supply chain of the UK’s dominant supermarket, Tesco, and their strategy to focus on customers’ needs rather than competing with other supermarkets [33].

Wright and Lund [34] found varying implementations of the ‘lean logistics’ approach, especially in terms of work monitoring, work intensification, reward systems, teamwork and employee involvement in the distribution systems in large Australian retailers. Jaca et al. [35] had similar results when developing a methodology for change management towards lean practices in distribution centres. The just-in-time aspect of lean management emerges when Evans and Harrigan [36] observe that there is a shift towards producing more locally, allowing for timely deliveries in response to demand fluctuations whilst avoiding large stock, although trends since then indicate more global supply chains especially in garment supply chains [37]. Green and Lean strategies may lead to both synergies and misalignments in logistics [38], depending on the operational profile of the company—low volume, high variety or high volume, low variety. In a study of supermarkets [39], lean-green approaches were found to bring improvements to both operational performance and sustainability. Cross-functional collaboration within the company and with suppliers promises to foster innovation [19,31], particularly in terms of reverse supply chains.

Four Principles [40] is, to the best knowledge of the authors, currently the only document discussing the detailed application of lean thinking to product returns and associated reverse logistics. In this research consultancy report, they point out the opportunity for manufacturers to improve product reliability and design by gathering customer feedback upon product return. Lean solutions for return can optimise reverse supply chains and shorten the lead time for a product to be resold. Furthermore, they emphasise that returns are an opportunity to eliminate waste through applying lean principles. The seven kinds of waste are identified as (1) over-processing of returned goods, (2) inventory costs of returned goods, (3) unnecessary transportation, (4) unnecessary motion of people dealing with returns, (5) delays due to badly integrated processes, (6) defects of returned goods that need dealing with and (7) use of space by returned goods. This provides a more detailed approach than the conceptual models in the academic literature, such as [29] and [19,31]. In particular, the use of third-party logistics companies in both distribution centres and returns centres appears to be absent from studies so far, as are the different configurations of supply chains. There may be an increase in the number of points at which waste and cost can occur with third parties [41,42], and this supports the aim in this paper to provide a more detailed mapping of the retail returns process to bring out the practical possibility of a leaner returns management.

3. Research Methodology

Process mapping was described [43] as a “proven analytical and communication tool” that can be used to visualise business processes that even managers often do not sufficiently understand. Process mapping can help determine where processes can be simplified, improved or eliminated. Starting with an “as is” map visualising the current situation, a “to be” map can be created to illustrate what an improved future system could look like. A complex example of process mapping is found in Fosso Wamba et al. [44], who mapped an involved network of companies as well as inter- and intra-organisational processes to improve the shipping and receiving processes in business-to-business eCommerce supply chains.

For the case of forward supply chains in the Dutch and Swedish retail industries, four case studies were conducted to map the processes involved in packaging at the manufacturer and logistics and arrival at the retailer [45]. The collected data was then triangulated from the individual cases to generate a generic map. Process maps help identify value-adding (or in the case of product returns, value conserving) activities, ultimately leading to more effective and efficient processes. Hellström and Saghir [45] explained that “mapping the physical flow and analysing the activities along the retail supply chain enhance the comprehension of the conditions of the logistics activities connected to packaging and their potential impact on the overall efficiency of the retail supply chain”. Equally, mapping the flows of products, information and communication as well as the associated activities and decisions to be made allow us to deepen our understanding of product returns processes.

We follow the process set out by Hellström and Saghir [45] but consider the steps needed to create ‘to be’ maps to sit along the ‘as is’ maps in Hunt’s approach [43]. To gain an in-depth understanding of product returns processes, we conducted four detailed, qualitative case studies and 17 interviews with retailers in the UK and Western Europe. The participating organisations were selected purposively, and access was obtained via an association of retailers and manufacturers. Such non-probability methods are used in qualitative studies where a specific ensemble of cases is selected for deeper investigation, which probability sampling could not provide [46].

We were able to compare practices and problems across the industry by investigating four major retailers. Our findings were validated through structured interviews and feedback from the industry. We also presented our work in forums of retail loss experts to identify any concerns with the validity of the data.

3.1. In-Depth Investigations

In the period between 2017 and 2019, we conducted four detailed case studies. The participating companies retail a wide spectrum of items, including groceries, clothing and household products such as home entertainment and small electrical goods. Their annual sales ranged from 11.8 to 55.3 billion Euros in 2015/16, shown in Table 1. The focus was on the returns processes and management of non-food items. We excluded food products due to their perishable nature, which restricts most returns processing.

Table 1.

Case study companies.

Individual and group interviews were conducted with members of staff and management who had interactions with and/or responsibility for returns from eCommerce. Interviews usually took half an hour to an hour, with an average of about 48 min, and were recorded. Across the four companies, we interviewed a total of 25 people with responsibilities in stores, (returns) distribution centre management, loss prevention and finance. Each case study involved several visits to stores, headquarters and distribution/returns centres. This allowed us to observe and discuss the returns processes in store (as experienced by customers, sales staff and including the “back of shop” processes) and upon arrival at distribution/returns centres for processing. Moreover, Company 2 provided data on the eCommerce returns volumes and associated costs, whilst Company 4 provided printouts of process flows for managing Click and Collect and returns of items purchased online and collected and/or returned in store.

3.2. Structured Interviews

To verify the findings of the case studies, data from a wider range of retailers were collected. We developed a guide for conducting structured interviews after analysing the first three case studies and conducted 17 interviews (mostly by phone) with other European retailers on this basis; more details in [8]. All interviewed retailers are large companies with over 250 employees and a turnover of over €50M.

The interviewer took written notes of the conversations. The participating retailers had volunteered to participate and verbally consented to take part.

3.3. Further Feedback

We verified the validity and applicability of our results by obtaining feedback from a wider range of retailers, suppliers, manufacturers and couriers. This was done via interactive workshops at ECR Retail Loss Community meetings in February and June 2018 and the ORIS Forums Summit in May 2018. Interactive surveys and roundtable discussions allowed us to gather the required feedback.

3.4. Data Analysis and Creation of the Process Map

During the visits to stores, warehouses and RCs, we followed the paths of returned goods to establish the processes. For each case study company, we then created a process map and had it verified by the returns process managers. We then merged the individual maps to create one generic map that included all path variants we had identified. The generic map was then presented at retailer association workshops, and company delegates, including those partaking in the structured interviews, were asked to verify that their own returns processes were indeed represented by the generic map.

For further confirmation, all in-depth interviews were thematically analysed, using close reading as well as manual coding. The interviews were studied together with additional notes taken during site visits to stores, distribution centres and headquarters (for instance notes from observing the returns processes).

3.5. Limitations of the Research

As typical for qualitative studies, we are unable to claim that these results are generalisable across the whole industry. The companies we investigated are mostly large retailers. Therefore, the data gathered and results formed may not entirely apply to smaller businesses. Additionally, the organisations came forward to participate in the project and hence are potentially more aware of product returns challenges than other retailers. Quite possibly, they manage their returns processes better than many other companies already. Hence, the case study retailers may offer more informed insight into the challenges and problems with product returns and best practices in the industry.

4. Mapping of the Product Returns Process

Retail returns processes are complicated. They often span multiple locations, go through many hands and can take weeks to complete—although, time is often crucial if products are to return to the shelf. Most products have some kind of expiry date; for instance, winter garments cannot be sold at full price in spring, and even non-seasonal articles are at risk of being out of series if they take a long time to return to the shelf.

The generic process described below is a synthesis of the processes observed in the case study companies and confirmed with various other companies. Not every company may have all the entry and exit points, or processes may vary a little, but all companies confirmed that they see their own system reflected in the generic process map.

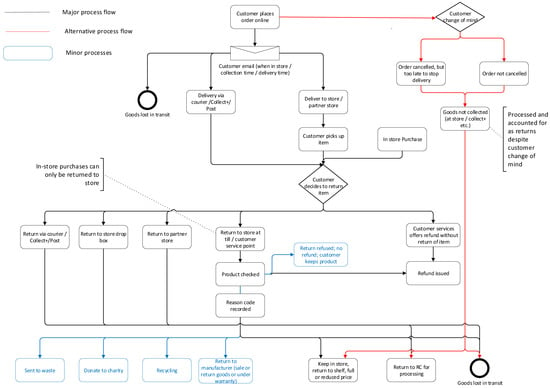

Figure 1 starts with the customer purchasing a product in store or ordering it for delivery at home, delivery to a parcel shop or Click and Collect. This then leads to the possibility of the customer refusing delivery or not picking up the order. In those cases, the items will eventually be placed on the shelves of the store or get sent to the Returns Centre (RC), in which case they might also be lost in transit. Assuming the customer does receive the item and decides that it needs to be returned, there are again various points of entry to the returns process: the item could be sent via courier, post or parcel shop; it could be returned to a drop-box, to a partner store or the main brand store via any till or customer services; or the customer might phone customer services and be offered a refund without needing to return the product.

Figure 1.

Generic process map, part 1—from purchase to RC.

Products returned to a (main brand) store might take various exit routes directly (in blue): a return might be refused, and the customer will keep the product; the item might go to waste; it might be donated to charity; it may go to recycling; it may be returned to the manufacturer/supplier; it could be kept in store to be sold again at full or discounted price; or it may be sent to the RC. Rarely, store employees would organise local transportation to a nearby store that carries the product and needs stock.

Products that are returned to the store need to be kept in a (relatively) secure space to reduce opportunities of theft whilst in holding. The transport between stores and the RC usually happens in so-called product cages, which are essentially trolleys with a metal grid around. They are usually open at the top and then get covered with plastic film or a plastic hood to reduce the opportunities for theft whilst in transport. A best practice observed at one retailer is to avoid all this single-use plastic and increase security by using a metal grid lid secured by a small seal.

All other returns process entry points lead to the items being sent to the RC. This is where Figure 1 ends. Note that the RC may either be independent at a separate location or integrated with the (forward) distribution centre. Distribution centres are often operated by third parties under open-book or closed-book contracts, which can make a major difference to the outcome in terms of whether returns are just handled as quickly as possible, or with the goal to maximise the retained value of the product and hence the achievable income for the retailer.

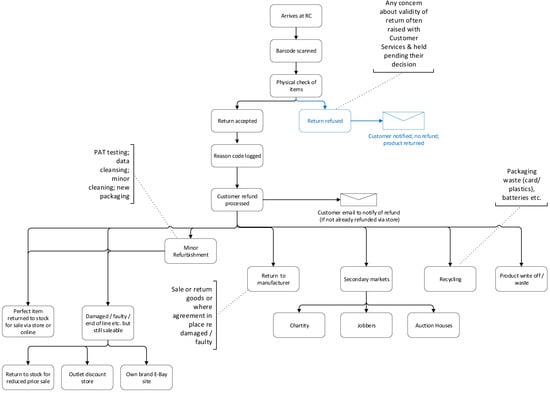

Figure 2 continues with the arrival at the RC, where the product’s barcode gets scanned and the product gets inspected. There is a small chance that a return may be refused, in which case the customer gets notified and the product is sent back to the customer. If the return is accepted, the return code gets logged and the refund issued (hoping that the system detects when a refund for the item has already been issued by a store assistant or a call centre employee).

Figure 2.

Generic process map, part 2—from RC to exit.

Products in perfect condition are then returned to stock for either online sales or to be sent out to stores. In some cases, products may undergo minor refurbishments at the RC, such as receiving a quick clean or getting new packaging (where this is available). If no fault is found, the product can return to normal stock. Imperfect items that can still be sold may return to stock for reduced price sales or be sold via outlet stores, physical or online. In some cases, the retailers will have agreements with manufacturers/suppliers for them to take back their products. However, lately, manufacturers no longer blindly accept all returns—only those that are related to warranty issues. Alternatively, items may go to secondary markets via charities, jobbers (third parties who buy mixed stock in bulk at minimal prices) or online auctions, which are slightly more targeted. Finally, products may go to recycling or waste, whilst some retailers promise not to send anything to landfill. However—especially for items below a certain threshold value that often cost more to process than they could generate in income—companies admit that they will choose the easiest/quickest/simplest exit route. Sustainability aspects are rarely considered at this stage.

Having mapped product return processes, the next step was to diagnose the retail challenges and opportunities associated with product return processes grounded in process management, sustainability and customer experience.

5. Challenges and Solutions Related to Returns Processes

Product returns processes are very complicated, involving multiple stages, players and channels. A walk through reveals many challenges, inefficiencies and vulnerabilities. The identified issues were classified according to where they occur; at the company side (store, transportation, RC), with the customer, somewhere in-between (in particular, returns codes) or at the level of strategic management. It is quite evident that to increase efficiency, product returns processes also need to be streamlined in general.

5.1. Company Side

One of the most striking problems with returns processes is the patchy IT systems in use. These are usually legacy from brick-and-mortar store times, to which online sales systems were added. Confronted with a multichannel reality, IT systems cannot communicate with each other, fail to track products throughout their journey and reconciling refunds with returned products becomes almost impossible. As a work-around, many retailers record and transfer data manually from one system to another, which is inefficient and failure-prone. Software companies offering integrated solutions have started to appear, but retailers are slow to adopt them.

The third parties who operate many RCs are often under pressure to process returns quickly as well as not being sufficiently trained to make decisions that are in the retailer’s best interest, i.e., to conserve the most product value possible. For instance, a product in perfect condition but with a slightly dented box may be sent to jobbing, whereas it could very well be sold again in store. With proper training and clear instructions (on paper, with illustrations, available at each work-station), decision-making at RCs could be optimised.

A related issue is that RC operator companies often work with a closed-book contract, meaning that the retailer and the RC operator company share very little data about the operations. This leads to suboptimal practices within the RC, as the operator has little incentive to ensure, for example, that those handling the returns cause little damage or choose the best exit route that maximises income for the retailer. Taking the above example, products that could have been put back on store shelves or resold online, even at a discount, due to slight damage of the packaging, were being sent to jobbers or even to landfill by RC handlers. The solution is to use open-book contracts with targets built-in. The third-party operator is paid a set amount for the contract, but incentives and bonuses are built-in related to loss reduction and mitigation, as well as efficiency of handling and throughput of items.

Where take-back contracts with manufacturers/suppliers exist, these should actually be used. Again, third-party operators need very clear instructions on what should and should not be returned to suppliers, as these no longer accept all returns without scrutiny as to whether they are damaged or faulty.

5.2. Returns Codes

As Bernon and Cullen [47] discussed, reverse flows of products may occur for a multitude of reasons, such as forecast accuracy and demand fluctuations, short product life cycles and many others. Here, we focus only on returns that involve the end customer.

In theory, all retailers use return codes, and they could be a very useful tool in identifying the reasons for returns. However, retailers use them very inconsistently, losing out on essential opportunities to reduce returns rates. For one, there is no emphasis on the importance for customers, store assistants or RC operators to record returns codes correctly. Often, the first option—which is usually ‘change of mind’—is selected out of laziness/convenience, as it is typically the option at the top of the list or the first item on the drop-down menu. It comes as no surprise that ‘change of mind’ features in 70% of returns reasons. Whether this reflects reality is an entirely different question altogether. Furthermore, different retailers use different sets of returns codes, also making it difficult to draw useful comparisons between businesses.

Correct and useful implementation of returns codes requires action from both company and customers. The retailer needs to define a consistent set of returns codes, present it on IT system menus and return slips such that ‘change of mind’ is not at the top of the list, and insist on employees collecting the data accurately when accepting returns. Customers equally need to complete their return slips correctly when returning items by post/courier. Retailers could incentivise customer compliance by offering some kind of benefit for a (hopefully) truthful returns code.

Saarijärvi et al. [12] identified ten drivers for customers to return products, without classifying them in terms of who caused the return, namely:

- Product defect

- Wrong product delivered

- Product found cheaper or faster elsewhere

- Discrepancy between expectations and product reality

- Too big/too small

- Does not feel right

- Customer overspent

- Product no longer needed

- More products ordered than needed

- Product ordered just to try it out

The last two reasons relate to what Rintamäki et al. [48] call “planned returns” as opposed to those that happen unintentionally.

With the goal to reduce returns rates, it is useful to identify who caused the return; hence, we suggest the following more complete and structured classification [49]:

Returns codes—Retailer’s fault

- Delivery too late

- Incorrect product delivered

- Delivered in a damaged state

- Substitute unacceptable (mostly applies to grocery items)

- Lost during transport

- Replacement was sent, original then found

- Picture/description online inaccurate

Returns codes—Manufacturer’s fault

- Part missing

- Manufacturing fault

- Customer unable to use or assemble the product—better manual required; this often results in “no fault found” cases, meaning either the technical problem was transient or the user was at fault, as discussed in Cullen et al. [50]

- Other warranty issue (later)

Returns codes—Customer’s fault

- Change of mind

- Selection ordered

- Ordered too many

- Wrong texture or colour (note that this might also be due to the website not representing the item accurately)

- Wrong size (note that this could also be the manufacturer’s or retailer’s fault, as items might deviate from standard sizes, or sizing charts might not be correct)

- Does not fit (same as above)

- Undesired gift

- Not collected

- Delivery refused

Having identified the true reasons for returns of each product, retailers would be able to take action accordingly. For instance, if a certain garment is often returned because the size fitting is wrong, this should be discussed with the supplier and corrected, or at least a warning should be placed on the website. People in procurement should then take the issue into account for future purchases. As another example, if returns codes indicate that customers struggle with the use of certain electronic devices and return them as ‘faulty’ whilst no fault can be found upon inspection, improved instruction manuals plus customer support via phone or web chat could help.

5.3. Customer Side

It is a common mistake to assume that offering more choices to do something-for instance many ways to return products-should be an advantage. However, it has been shown [51,52] that this is not the case. It may be better to offer just one or two options and give very clear instructions on how to proceed, avoiding any ambiguity. Fewer options mean less confusion for customers and simpler processes for retailers and RC operators.

People are often unaware of the economic and ecological consequences of their choices. For instance, it may be similarly convenient for a customer to return a product to store, to a parcel shop or to have it picked up by a courier. If given sustainability information regarding each option, many customers may even be willing to make an extra effort to reduce the impact of their actions. An example illustrating this is Ocado (a British grocery delivery service) showing a green van symbol in their delivery slot booking system when a delivery in the same neighbourhood is already booked for a certain slot.

Similarly, customers could be given information about how their purchasing and returning behaviour affects the company—for instance, indicating the costs of each return to the company, and how it could be reduced.

Lately, illegitimate “borrowing” has become increasingly socially acceptable, either in the form of “wardrobing” (buying fashion items with the intention of producing pictures for Social Media or attending an event, then returning them) or purchasing a large-screen TV for watching a sports event/children’s toys or bikes to use during the summer holidays and then returning them. Many companies struggle to stop this trend due to their emphasis on excellent customer service. Whilst most returns policies likely point out that this is not allowed, customers are rarely made aware of this fact when making a purchase. Doing this may trigger at least some of the offenders to reconsider their actions. An additional option could be for retailers to provide information about ‘Libraries of Things’ or other borrowing schemes for those customers who do not intend to keep the product.

5.4. Strategic Management

The most fundamental problem identified in this research is that returns are not seen as a priority by businesses; rather, they are considered an unavoidable cost of doing business. This leads to neglect, a missing oversight at the senior management level and a lack of readiness to invest in better IT systems, for instance. We showed in [8] that reducing the rate of returns and making returns systems more efficient has a direct effect on the bottom line, i.e., business profitability can be improved without the need to generate any additional sales. Therefore, we argue that companies need to make returns a strategic management priority; they need to designate a returns director who will measure and monitor returns processes, and investments into suitable IT systems need to be made. This could be either via custom-made systems for the company or using one of the recently emerging service providers who offer complete solutions.

So far, sustainability in product returns is not seen as a priority by most retailers [14]. There are, however, some exceptions. Many of the companies that implement Circular Economy (CE) principles were founded on this basis recently and cater to niche markets, such as Patagonia (outdoors clothing), Freitag (bags) or Thread International (packaging and textile fibres). On the other hand, major manufacturers and retailers that currently embrace CE principles often only do so for a minor sector of their business, such as:

- Fashion brands collecting textiles for recycling (M&S, H&M, Levi Strauss, etc.)

- Particular lines of clothes or shoes made from recycled materials (Nike, Levi Strauss, etc.)

- Packaging of certain product lines made from single, easily separable materials (Lidl, Tesco, etc.)

This is an indication that whilst CE principles do function, implementation tends to take time to scale up due to the required effort and the human reluctance to change. Examples include replacing multilayer materials with single, easily recyclable materials. Many consumers still hesitate to purchase remanufactured products, as they may appear less appealing and of lower quality. Additionally, the costs of remanufacturing need to be balanced against the expected profit margin [53,54].

6. Discussion

Product returns in multichannel retailing pose a challenge that is frequently underestimated. Research in this field is emerging, and multidisciplinary efforts are needed to address the many problematic aspects. This article contributes to the body of knowledge in product returns by mapping out the complexity of returns processes in a generic form, showing multiple possible points of entry and exit. Such process maps were created for forward supply chains in retail [45], but existing literature on product returns and reverse supply chains in retail, such as [22,23], did not include detailed process maps as presented here.

Furthermore, vulnerabilities and inefficiencies in the returns system are identified and possible solutions suggested. This includes a taxonomy of returns codes, which presents valuable opportunities for retailers to identify causes of high return rates and ways to reduce them, which would have a direct effect on the bottom line. Product returns data needs to be collected and monitored systematically and reported to senior management.

While we identified a number of examples of lean thinking in retail, similar to those reported in [32,55] and elsewhere, we found that returns processes are not lean yet and this is clear from the process maps that we have produced. Conceptually, in a functioning forward lean thinking system, there should not be any defects or waste and a culture of “getting it right the first time”. This would mean few or (ideally) no returns. It is very obvious that this is not the case in practice. Lean processes do exist in sales, and similar processes are needed for returns for the two to become integrated. It is necessary to think in reverse to address the issue of product returns, and we could name this ‘lean thinking reverse logistics’ or ‘lean product returns management’.

For example, the emphasis on the customer first in sales distracts from the necessary thinking required in a lean returns system. Simply, the retailer becomes the recipient of the goods or, in other words, is now the customer, with the original customer being the seller. Effective delivery of value to the customers on either side in the product returns scenario means considering how retailers can retain value from returned products.

Returns consist of a push system based on supply rather than a pull system based on demand. It is possible to forecast supply to some degree based on previous returns, but it remains only partially predictable. What retailers can control is how products are pushed through returns exit routes and hence strive for a pull system such as it exists in product sales. An example in a purely online retail system would be the limited number of ways that Amazon allow for returns to be made to their returns centres and the clarity with which the customer is guided through the process of making the return in the way that suits the multinational corporation. This is underpinned by patented algorithms US8156007B1, US9727873B1 and US9692738B1, for example. Röllecke et al. [56] also cite Amazon as being a key example of a company that has managed to find a management model for returns that balance cost reduction and customer service.

The way reverse logistics are organised has developed over the last few years, now only three or four strategic steps persisting instead of what previously used to be a dozen steps [57]. Companies desiring to increase profits need to streamline their returns systems and ensure that senior management takes responsibility [58].

From our empirical data, we broadly find support for [40] in the opportunities for eliminating waste and the assertion that product returns should be considered as assets [28]. There is further work to be done, however, to conceptualise the management control systems needed, including the organisation of cross-functional teams managed from the executive management level. Lean returns management needs to encompass lean accounting systems, monitoring and evaluation and data management. The implications of treating returns as a profit rather than as a cost centre are vital so that emphasis is placed on savings and income generation, rather than simply costs and losses. Conceptually, this would include increasing the environmentally sustainable actions available to retail businesses through their returns process.

Röllecke et al. [56] observe that “Returns management is still in its infancy. The conditions giving rise to its strategic role have existed for no more than about two decades, driven as they were by the unprecedented growth of e-commerce.” A contribution here is to open up a discussion about what lean management looks like in a multichannel retail environment. Re-engineering the returns process could provide the knowledge retail businesses need to develop themselves in the transition towards seamless omnichannel environments in line with current ideals in customer service. In brief, operational improvements that profit protection managers can achieve through lean management of returns require:

- Mapping out the reverse logistics processes to remove unnecessary steps

- Improving communications with customers to reduce rates of returns

- Improving communications with employees to maximise income from returned products

- Identifying opportunities to improve data collection as well as information processing

As academics, we should look to conceptualise and create a theoretical framework for lean product returns, and the process maps that we provide here of the systems ‘as is’ can be the basis after future empirical work of ‘to be’ maps. In addition, further action research or other empirical research work is needed with retailers to develop lean returns processes.

7. Conclusions

Retailers and academics have recently started to become aware of the importance and scale of the product returns problem, but it remains an underestimated and understudied field. The mapping we have undertaken and presented in this article, based on rich empirical data, shows clearly that product returns in a multichannel environment provide a starting point for improving both product management and sustainability for retailers. It is essential to make product returns a priority at the strategic management level, especially in view of the current economic situation, the transition towards omnichannel business models, the challenges global supply chains are facing and the environmental crisis—which calls for much greater sustainability in all aspects of human life, including retail and returns.

For academics, we highlight the opportunity to formulate a lean returns management conceptual framework based on further empirical and action research. We suggest that the starting point for conceptualising lean returns management is to consider the pull factors from the retailers’ point of view and to find systems that reduce cost and waste for retailers whilst maintaining customer satisfaction. We contribute to the development of the field of study by providing process maps based on detailed empirical investigation of the issues facing retailers as returns become an increasing burden on resources and a challenge for the maintenance of customer satisfaction. For practitioners, we provide structured opportunities to improve their returns systems whilst rethinking their strategic management and business model. Product returns might even be considered as an opportunity to move towards an access-based business model [59].

The limitations of this work include that it represents the situation of UK and Western European retailers; those elsewhere in the world may find that their processes are different and remain to be investigated in future studies. The authors are currently investigating the influence of the pandemic on product returns. Future research could address the potential of artificial intelligence to mitigate product returns and related fraud, the details of fraudulent returns behaviours, the benefits and challenges of implementing a sustainable returns strategy and related environmental assessment methods.

Author Contributions

Funding acquisition, L.J.; Investigation, R.F., L.J. and S.-A.K.; Visualization, S.-A.K.; Writing—original draft, R.F. and S.-A.K.; Writing—review & editing, R.F. and L.J. All authors contributed to all parts of the research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the ECR Retail Loss Group (https://www.ecrloss.com, accessed on 3 December 2021); no grant number.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Portsmouth Business School Ethics Committee (approval reference E426, January 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dias, E.G.; Oliveira, L.K.d.; Isler, C.A. Assessing the Effects of Delivery Attributes on E-Shopping Consumer Behaviour. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Paswan, A. Consumers’ legitimate and opportunistic returns behaviours in online shopping. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 19, 301–319. [Google Scholar]

- Frei, R.; Jack, L.; Brown, S. Product returns: A growing problem for business, society and environment. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, L.; Frei, R.; Krzyzaniak, S.A. The Hidden Costs of Online Shopping—For Customers and Retailers. The Conversation. 21 January 2019. Available online: https://theconversation.com/the-hidden-costs-of-online-shopping-for-customers-and-retailers-109694 (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Terry, L. Managing Retail Returns: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Inbound Logistics. 2014. Available online: https://www.inboundlogistics.com/cms/article/managing-retail-returns-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly/ (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Daine, T.; Winnington, T.; Head, P. Transition from push to pull in the wholesale/retail sector: Lessons to be learned from lean. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2011, 8, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. Reconceptualising loss in retailing: Calling time on ‘shrinkage’. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2017, 27, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, L.; Frei, R.; Krzyzaniak, S.A. Buy Online, Return to Store; The Challenges and Opportunities of Product Returns in a Multichannel Environment. Research Commissioned by the ECR Shrink Group. 2019. Available online: https://ecr-shrink-group.com/page/buy-online-return-in-store-no-such-thing-as-a-free-return (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Getz, D.; O’Neill, M.; Carlsen, J. Service quality evaluation at events through service mapping. J. Travel Res. 2001, 39, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.C.; Duarte, P.; Sundetova, A. Multichannel versus omnichannel: A price-segmented comparison from the fashion industry. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakulenko, Y.; Shams, P.; Hellström, D.; Hjort, K. Service innovation in e-commerce last mile delivery: Mapping the e-customer journey. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarijärvi, H.; Sutinen, U.M.; Harris, L.C. Uncovering consumers’ returning behaviour: A study of fashion e-commerce. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2017, 27, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foscht, T.; Ernstreiter, K.; Maloles, C.; Sinha, I.; Swoboda, B. Retaining or returning? Some insights for a better understanding of return behaviour. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2013, 41, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, R.; Jack, L.; Krzyzaniak, S.A. Sustainable Reverse Supply Chains and Circular Economy in Multichannel Retail Returns. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1925–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.; Dennis, C.; McHendry, J. The management of deshopping and its effects on service: A mass market case study. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2007, 35, 720–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, R.A.; Sturrock, F.; Ward, P.; Lea-Greenwood, G. Deshopping—The art of illicit consumption. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 1999, 27, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, T.L.; Jack, E.P. Understanding the causes of retail product returns. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2015, 43, 1182–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.C.; Yurchisin, J. Fast fashion environments: Consumer’s heaven or retailer’s nightmare? Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernon, M.; Tjahjono, B.; Ripanti, E.F. Aligning Retail Reverse Logistics Practice with Circular Economy Values: An Exploratory Framework. Prod. Plan. Control. 2018, 29, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beh, L.; Ghobadian, A.; He, Q.; Gallear, D.; O’Regan, N. Second-life retailing: A reverse supply chain perspective. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 21, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernie, J.; Sparks, L.; McKinnon, A.C. Retail logistics in the UK: Past, present and future. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2010, 38, 894–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernon, M.; Cullen, J.; Gorst, J. Online retail returns management: Integration within an omni-channel distribution context. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2016, 46, 584–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjort, K.; Hellström, D.; Karlsson, S.; Oghazi, P. Typology of practices for managing consumer returns in internet retailing. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 767–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Yang, M.L.; Wong, Y.J. Institutional pressures, resources commitment, and returns management. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2016, 21, 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwitz, N.; Maas, P. Understanding the omnichannel customer journey: Determinants of interaction choice. J. Interact. Mark. 2018, 43, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Amorim, M.; Bhattacharya, A.; Garza-Reyes, J. Managing reverse exchanges in service supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 21, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, A. Extended TPB model to understand consumer “selling” behaviour: Implications for reverse supply chain design of mobile phones. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 721–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibben-Lembke, R.S.; Rogers, D.S. Differences between forward and reverse logistics in a retail environment. Supply Chain Manag. 2002, 7, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, J.D.; Badenhorst, A. A conceptual framework for reverse logistics challenges in e-commerce. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2020, 21, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollenkopf, D.; Russo, I.; Frankel, R. The returns management process in supply chain strategy. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2007, 37, 568–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernon, M.; Rossi, S.; Cullen, J. Retail reverse logistics: A call and grounding framework for research. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2011, 41, 484–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukic, R. The effects of application of lean concept in retail. Economia. Ser. Manag. 2012, 15, 88–98. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, B.; Mason, R. The Lean Supply Chain: Managing the Challenge at Tesco; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, C.; Lund, J. Variations on a lean theme: Work restructuring in retail distribution. New Technol. Work Employ. 2006, 21, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaca, C.; Santos, J.; Errasti, A.; Viles, E. Lean thinking with improvement teams in retail distribution: A case study. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2012, 23, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.L.; Harrigan, J. Distance, time, and specialization: Lean retailing in general equilibrium. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 292–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börjeson, N.; Boström, M. Towards reflexive responsibility in a textile supply chain. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Rodrigues, V.S. Synergetic effect of lean and green on innovation: A resource-based perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 219, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.A.; Carvalho, A.M.; Santos, J.O. Improving Operational and Sustainability Performance in a Retail Fresh Food Market Using Lean: A Portuguese Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Four Principles, Lean Reverse Logistics. 2018. Available online: https://fourprinciples.com/our-expertise/functional-solutions/reverse-logistics (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Yao, W. Logistics network structure and design for a closed-loop supply chain in e-commerce. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2005, 7, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weixin, Y. Atomic models of closed-loop supply chain in e-business environment. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2006, 8, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, V.D. Process Mapping: How to Reengineer Your Business Processes; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fosso Wamba, S.; Lefebvre, L.A.; Lefebvre, E. Integrating RFID technology and EPC network into a B2B retail supply chain: A step toward intelligent business processes. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2007, 2, 114–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström, D.; Saghir, M. Packaging and logistics interactions in retail supply chains. Packag. Technol. Sci. Int. J. 2007, 3, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.A. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Realist Approach. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2017; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bernon, M.; Cullen, J. An integrated approach to managing reverse logistics. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2007, 10, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintamäki, T.; Spence, M.T.; Saarijärvi, H.; Joensuu, J.; Yrjölä, M. Customers’ perceptions of returning items purchased online: Planned versus unplanned product returners. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2021, 51, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, R.; Jack, L.; Krzyzaniak, S.A. Sustainable reverse supply chains for retail product returns. In Sustainable Development Goals and Sustainable Supply Chains in the Post-Global Economy; Yakoleva, N., Frei, R., Murthy, S.R., Eds.; Greening of the Industry Network book series; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, J.; Tsamenyi, M.; Bernon, M.; Gorst, J. Reverse Logistics in the UK retail sector: A case study of the role of management accounting in driving organisational change. Manag. Account. Res. 2013, 24, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, A.B.; Maxham, J.G., III. Return shipping policies of online retailers: Normative assumptions and the long-term consequences of fee and free returns. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.M. Is more choice always desirable? Evidence and arguments from leks, food selection, and environmental enrichment. Biol. Rev. 2005, 80, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, R.K.; Vrat, P.; Kumar, P. Cost optimisation model in recycled waste reverse logistics system. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2004, 6, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, G. A metaheuristics-based decision support system for the performance measurement of reverse supply chain management. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2009, 11, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myerson, P. Lean Retail and Wholesale; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Röllecke, F.J.; Huchzermeier, A.; Schröder, D. Returning customers: The hidden strategic opportunity of returns management. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 176–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. Retail Survey 2017. 2017. Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/uk/pdf/2017/02/retail-survey-2017.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Sciarrotta, T. Directing Reverse Logistics—A Corporate Paradigm Shift. Reverse Logist. Mag. 2018, 4, 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Baden, D.; Frei, R. Product Returns: An Opportunity to Shift towards an Access-Based Economy? Sustainability 2022, 14, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).