Abstract

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has been an articulated practice for over 7 decades. Still, most corporations lack an integrated framework to develop a strategic, balanced, and effective approach to achieving excellence in CSR. Considering the world’s critical situation during the COVID-19 pandemic, such a framework is even more crucial now. We suggest subsuming CRS categories under Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) be used and that they subsume CSR categories since SDGs are a comprehensive agenda designed for the whole planet. This study presents a new CSR drivers model and a novel comprehensive CSR model. Then, it highlights the advantages of integrating CSR and SDGs in a new framework. The proposed framework benefits from both CSR and SDGs, addresses current and future needs, and offers a better roadmap with more measurable outcomes.

1. Introduction

Businesses create new jobs and produce wealth. But if they fail to act responsibly, they can also pose a threat to society and the environment. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) can mitigate corporate damage by encouraging socially responsible, and environmentally-friendly, actions [1]. A CSR plan establishes a strategy to support socio-economic and environmental sustainability through management and stakeholder involvement [2]. An increasingly populated planet struggling with massive climate change problems provides evidence of why businesses should not engage in CSR from a solely local context since they exist within an interconnected world. Short-term corporate actions have irrefutable impacts on the environment, society, and economy which is why the long-term perspective of CSR is important for the health of the planet.

The current pandemic of COVID-19 has highlighted the significance of CSR. Humans are now more aware than ever of how connected everyone is around the globe, and how irresponsible action can wreak havoc for all. The Coronavirus began with just one person, spread through global travel and product transports, and in less than a year, it spread to nearly every country [3]. Social life has changed since the COVID-19 outbreak. The global stock market fluctuation, the quarantine measures, and social distancing were just some of the effects. Businesses are negatively impacted by the Corona Virus [4] such as temporary or permanent closures, layoffs [5], and cash flow constraints [6]. Such unexpected changes in the world highlight the importance of CSR. It could motivate companies to revise their approach to social responsibility, realizing that a simple mistake or irresponsible action would have a major impact worldwide. Meanwhile, corporations recognize the need to equip themselves with risk and emergency management tools for their own benefit as well as that of their society [7].

CSR played a huge role in the business world even before the start of the pandemic. Corporations have invested in socially responsible plans out of ethical and philanthropic purposes or financial ones for years. But not many of these plans were systematically designed. Each company scanned their society’s issues and challenges, picked one or a few of the matters based on their own limited knowledge, and tried to make a small difference in a localized context. Most companies did not have the facilities to properly measure the final effects of their contributions. A well-designed framework, the most comprehensive one in the world, is proposed in this study to help companies structure their CSR plans. This framework is the SDGs mapped out by the United Nations (UN).

According to the United Nations [8], Sustainable Development is “the development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. SDGs consist of 17 goals, as illustrated in Tabe-2, over the period of 2015–2030. Individuals, communities, small businesses, and large corporations all benefit from the SDGs [9]. Global experts’ knowledge and the opinions of governments, organizations, institutions, as well as the voices of millions of people were used to establish the SDGs. The 17 Sustainable Development goals are an ideal framework for CSR plans. In addition to addressing the same general purpose as CSR, which is the wellbeing of society, SDGs are based on the problems of the current and future world. The SDGs receive funding every year, and their impact has been substantial. The SDGs are already widely known and globally recognized, making this course of action an immediate opportunity. This study demonstrates how SDGs as a framework for CSR will benefit people, the planet, and corporations themselves. Additionally, the SDGs serve as a basis for the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Community Development Program (CDP), the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), and the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSP). Corporations’ contributions to the SDGs are disclosed by these institutions. Furthermore, these five standard-setting institutions have formally agreed to work together to develop a comprehensive report on corporate sustainability and corporate responsibility in September 2020 [10], that enhances CSR communication of firms if they are SDG-related.

This study offers a new perspective on CSR implementation: a perspective that results in worldwide and sustainable impacts. We first investigate CSR drivers in a way that no one has done before, and suggest CSR benefits for corporations on the basis of recent literature reviews then introduce a new model for CSR that integrates previous models and also adds new dimensions. Second, we introduce the SDGs and discuss their status and significant progress around the world based on the United Nations’ annual reports. Finally, we discuss all 17 goals of the SDGs from the perspective of how they can benefit corporations, and propose our comprehensive framework for CSR implementation based on the SDGs.

2. Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility was formulated as a cohesive concept in the 1950s and expanded in the 1960s [11]. The debate was whether corporations should go beyond their own shareholders’ value to support society’s needs, or such effort was beyond corporations’ responsibilities. To be effective, CSR must combine theory with practice. Fortunately, since the 1960s, both corporations and researchers have played a huge role in developing CSR [12].

CSR has a close relationship with a variety of terms and concepts that have evolved over time: Corporate sustainability [13], corporate citizenship [14], corporate responsibility [15], corporate social performance [16] corporate reputation [17,18], business ethics [19] and corporate philanthropy [20]. This article, however, will focus on the original concept.

Currently, the Coronavirus pandemic has highlighted the importance of businesses CSR strategies. In response to the crisis, some corporations remained loyal to their understanding of ethics, some “stepped up” and helped their society with all the means at their disposal, while some others took advantage of the situation and tried to gain short-term benefits [21]. The long-term consequences of such short-term profit-taking, however, can lead to reputation damage, or even worse, missing out on opportunities to improve their public image and credibility. Through the pandemic corporations have been forced to choose between helping society or focusing on their survival. Some companies have chosen to use SDGs as a guideline in order to create a balance between their own interests and society’s wellbeing [22]. Some examples would be investments that generate stock returns [23,24] or investments in COVID-19 protection, prevention, treatment and rehabilitation [25] to offset the economic and health-related impacts of COVID.

With the global Coronavirus outbreak, the world has realized the importance of CSR more. As an example, in the case of many companies, supply chains are experiencing disruptions in supply, cancellation of orders, delayed payments, reductions in sales, and financial difficulties [26]. Under such circumstances, a portion of a corporation’s CSR budget could be allocated to their supply chain partners in the form of loans or donations, which would be of great help until the crisis is over. In return, corporations keep their reliable suppliers and avoid transition costs and risks. Another example would be corporations that support their employees’ health and financial status by preparing the infrastructure for them to work from home. As a result, employee satisfaction and trust increased, while the risk of employee loss was decreased. In this extraordinary period of time, companies are constantly reviewing their CSR strategies to determine what society expects from them [27].

In the following subsection, we investigate drivers that encourage or even force corporations to participate in CSR activities.

2.1. CSR Drivers

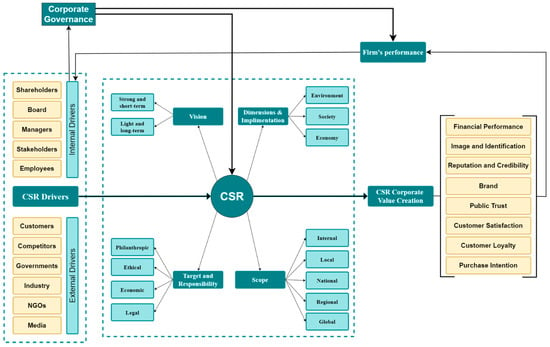

Consumers, internal employees, corporate managers, competitors, and the local community positively affect CSR contributions. There is a positive relationship between media, NGOs, governments, suppliers and investors with the CSR motivators [28]. Next, we investigate eleven drivers of CSR as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The Model of CSR drivers.

Shareholders: Shareholders own the company; therefore, they own its decisions. They have real effects on society [29]. What investors believe dramatically affect the CSR performance of a company [30]. For example, shareholders are more willing to consider CSR budget investments if they believe in philanthropic and ethical activities [31].

Board of Directors: shareholders along with directors and managers form the corporate governance team and make major decisions for the firm. The board’s decisions determine the firm’s performance therefore they have the power to promote CSR. nowadays board members role in CSR implementation is increasing [32]. As an example, the presence of women and diversity on the board is making boards more likely to drive CSR [33,34].

Managers: Managers’ experiences alter their CSR implementation. They are more likely to take preventable actions if they recognize the risk and harm their corporation poses to society. Thus, by making social problems more visible, managers contribute to CSR more [35]. CEOs who have been in their position for a longer duration tend to have a better CSR resume. CSR outcomes are not immediately visible; therefore, managers consider it as a long-term investment [36]. Furthermore, CSR investments enhance corporate management performance [37]. Small, medium and large-sized companies, whether international, multinational, or local can play a role in CSR evolution if they invest in it over time [38].

Stakeholders: Stakeholders push CSR. They demand job security and stability, safety and health, gender equality, labor and workforce equality as well as human rights and ethics. Corporations intend to meet stakeholders’ expectations [39]. Stakeholders’ expectations are related to air, energy, waste, and water concerns [40], health and safety at work, ethical behavior, social investments (Seibert et al., 2021), and transparency [41]. Firms’ performance and communications productivity improve when external stakeholders participate in CSR-related activities and policy settings [42].

Employees: Employee performance shapes the company’s output, so human resource CSR training is required. The result would be the sum of employees’ micro-level CSR activities which are indisputable [43]. CSR motivations are linked to the employees’ personal identification and purposes [44] in addition to prosocial motivation and perception [45]. Managers are able to ensure that the intentions and necessity of CSR activities are clear to their personnel. When employees perceive their micro operations as a part of their company’s CSR plan, they are more likely to commit to it [46,47]. Employees positively react to their corporation’s CSR strategy if it improves their work environment and quality of life [48].

Customers: CSR is an important parameter for customers. Customers with financial burdens prioritize price over characteristics, but CSR awareness affects their purchase decisions [49]. People recommend socially responsible productions to others, which indicates that CSR promotes word of mouth recommendations [17]. CSR is more essential when corporations need customer support, such as when they face tremendous competition or reputation loss [36]. CSR enhances customer’s trust [50] and commitment [51] through reputation [52], and it results in customer loyalty and customer satisfaction [53]. It is not just local customers, national and international buyers have a significant power to impose CSR responsibilities on corporations too [54].

Competitors: Competitors encourages corporate environmental responsibility [55] which has a positive impact on environmental performance of the businesses [56]. Watching their competitors win CSR awards increases companies’ CSR contributions to remain competitive, especially in companies with similar management structures [57].

Governments: Governments seek to ensure market stability. They define norms and principles for CSR contributions and compel corporations to follow such principles [58,59]. CSR interventions [60] such as government subsidies [61,62,63,64], government support [65], government development programs [66], and government CSR regulations [67,68] are only a few forms of governmental involvement in the field.

Industry: Some industries are more critical in terms of their CSR contributions; some create less harm to the environment; and some are already helping society without CSR master plans. Although there are some general activities such as charity, each industry has its own sets of activities that can help the corporation become more responsible. For example, the implementations of CSR in the tourism industry [69], food industry [70], hospitality industry [71], banking industry [72], fashion industry [73], and the mining industry [74] vary depending on their conditions.

Media: The media affects corporations’ image and reputation. Corporations can use media in their favor by being transparent about their business and broadcasting their CSR activities [75]. Social media can be used to communicate CSR [76] allowing organizations to send intentional messages and create desired impacts on customers, stakeholders, and society.

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs): NGOs, directly and indirectly, push CSR activities. They use their facilities, settle contracts with companies, and raise awareness about CSR [77]. They help companies and encourage them to do their share for the society. NGOs can rather be slow moving, but they can be quite productive [78].

All eleven of these drivers are considered in an integrated CSR strategy. Depending on the circumstances, some CSR drivers might appear more impactful than the others and affect the strategy setting more than others.

2.2. CSR Benefits for Corporations

By reducing poverty, hunger, discrimination, inequality, and irresponsible consumption, corporations strengthen society, which includes the corporations’ potential customers as well. Companies enlarge their market by empowering vulnerable people. As illustrated in Table 1, CSR activities enhance a corporation’s image and brand, reputation and recognition, public trust and identification, customer satisfaction and loyalty, purchase intention, financial performance, access to capital and markets [79], and transparency [80,81]. CSR activities contribute to the management development, business decency, human rights, mutual benefits, and protect the future for the next generation [39].

Table 1.

CSR Direct Benefits for Corporations (CSR Corporate Value Creation).

Social welfare and the corporations’ success are interdependent therefore, CSR activities create shared value for both corporations and their societies [82,83]. CSR is a win-win value creation strategy [84,85]. According to some of the latest research around the world, Table-1 represents eight top benefits that CSR brings to corporation which are the value created by CSR implementations and directly impacts the corporations, enhances the firms’ performance, and consequently positively affects shareholders, stakeholders, the board of directors, managers, and employees.

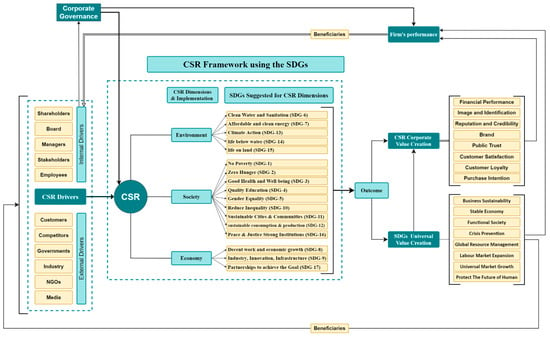

2.3. Comprehensive CSR Model

CSR activities go beyond ethical and philanthropic purposes. They add value to companies. CSR is more than keeping socially responsible; it is also about business profitability. Corporate governance on the other hand, provides a balance between the corporation’s survival and financial performance, which are in the shareholders’ highest interests, and the interests of stakeholders, which indirectly promote CSR [32]. The corporate governance mechanisms protect the interests of shareholders, managers, directors, employees, and other stakeholders [130,131]. Internal corporate governance aids in maximizing the firm’s profit, and CSR is one effective way to do so since both corporate governance and CSR enhance firms’ performance [132] as shown in Figure-2.

Figure 2 also illustrates four aspects of CSR including (1) CSR targets and responsibilities, (2) visions, (3) scope, (4) impact and implementation dimensions combined with CSR drivers (based on Figure-1) and CSR corporate value creation (based on Table-1).

Figure 2.

CSR model integrating drivers, implementation, target, vision, scope, and outcome.

CSR is encouraged by eleven drivers, as discussed earlier. And corporations have their own targets as a response to CSR drivers’ demands. As they implement long-term and short-term CSR visions to achieve their current and future objectives, they also consider the scope of their CSR strategies based on the area of their firm’s impact. They then implement their social, environmental, and economic CSR plans which brings them both short- and long-term corporate benefits which are the value created by CSR activities. Such value results in the firm’s performance development and eventually will benefit the internal CSR drivers the most.

Targets: Based of Carroll’s Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility (Carroll, 1991), corporations contribute to CSR for four purposes. First, philanthropic responsibilities are based on public expectations. According to this purpose, corporations dedicate their resources to develop the well-being of their community and society. The second purpose is ethics, which means corporations avoid harming their natural and socio-economic environment by doing what is right and just. Next governmental legislation can bolster CSR and motivate corporations to contribute more, by providing subsidies, or privileges over corporations’ competitors [65]. The last purpose is financial. As illustrated in Table-1, CSR positively affects corporate image and reputation, brand, customer loyalty and satisfaction. It increases purchase intentions, and consequently, profits.

Vision: A company’s CSR investment is based on its expected return. Top business strategies require long-term visions. That is why CSR strategies better consider long-term outcomes as well as immediate benefits. Corporate status plays a role in this choice. Companies choose short-term plans over long-term ones when there is a crisis or emergency forcing them to act immediately or they demand instant results. However, we recommend that companies adopt their CSR strategies in a way that leads to long-term and sustainable results.

Scope: CSR is applied on a global, national, regional, local, or even internal scope. As a result of their global value chains and markets, international and multinational corporations affect more people. National businesses cover a smaller area relatively, and local businesses focus their CSR activities on their local or regional community and limited number of stakeholders. Internal CSR is important since employees and shareholders are directly affected by the decisions of corporations [133]. Employees’ health and safety, education and development, human rights, and salary are examples that are directly the corporations’ internal responsibility [134].

Dimensions and Implementation: CSR implementation targets can be chosen based on purposes and circumstances. Companies implement environmental CSR [135] by compensating for damage already done or by implementing preventive activities to protect the current and future environment. Or they can directly contribute to society such as building schools and healthcare institutes, education and social awareness, and promoting equality in the workplace. The last option is to promote local and global economies through shareholders’ benefits such as employees’ income, customers’ budget, and stakeholders’ profit. To sum up, corporations invest their CSR budget in three areas: environment, society, and economy [136].

3. Sustainable Development Goals

Thousands of people around the world suffer from poverty, hunger, discrimination, inequality, unemployment, and life-destroying diseases. Furthermore, they may face natural disasters as a consequence of rising sea levels, climate change, desertification, and biodiversity destruction, among others. Natural, economic, and social problems cannot easily be addressed. However, to create a better world, the SDGs are the well-thought out and comprehensive policy agenda. UN adopted the SDGs in September 2015 to tackle environmental, social, and economic challenges of the next 15 years [137], taking current and future needs into consideration. It is proposed around the 5Ps (people, planet, peace, partnering, and prosperity) [8]. The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the SDGs in an unexpected way. Some SDGs progress was reversed, some activities were put on hold, and the chances of reaching 2030 targets have decreased.

The United Nations Sustainability Index Institute (UNGSII) published the SCR500 2019 report which investigated the 500 largest worldwide corporate investments [138]. More than 85 percent of those corporations spent budget on the SDGs and reported their contributions in their annual reports. In 2021, the reported number rose to 95 percent [139]. In 2019, SDG-13 and SDG-12 were globally considered most while the SDG-1 and SDG-14 were the least addressed among 17 goals. In 2021, visibility increased in 14 goals, especially SDG-8, which was predictable given the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the Asia-Pacific and the Americas corporate contributions were least visible, and most visible in Africa and Europe. Most likely it’s because of differences in SDGs communication culture. Airlines, banking, cars, food, insurance, tech, telecommunication, and pharmaceuticals were six of the most sustainable industries in this panel. Based on Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021, 75 countries kept their SDGs score above 70, and 17 of them even maintained a score above 80, which is remarkable considering the world’s average index drop in 2019 (Score 100 indicates the country contributes to all 17 goals)[140]. The bottom line is that only 5 percent of the biggest global corporations are not discussing the SDGs in 2021. In Table 2, we compiled a brief summary of the Sustainable Development Goals Report of 2021.

Table 2.

The summary of The 2021 Sustainable Development Goals Report [141]. (Based on the United Nations Report 2021).

4. Sustainable Development Goals and Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporations have the resources, manpower, and technology necessary to pursue SDGs, which makes them responsible to society. Based on the CSR Triple Bottom Line theory [142,143], CSR is a business model that embodies ethics by making a balance between economic interests, environmental needs, and social expectations.

Although CSR is a key to obtain sustainability [37], it also is a self-driven contribution to Sustainable Development [144] and it promotes SDGs [145]. However, a comprehensive plan is required to distribute the CSR budget and prioritize the SDGs’ targets by their necessity and emergency [146]. Sustainable Development focuses on ethics, human rights, society, economy, environment, and corporations. CSR, however, focuses on the environment, society, stakeholders, ethical behavior, and volunteering [147]. Sustainable Development offers a balance between pursuing the present needs of corporations, while protecting the future of humans and natural resources [148].

Corporate contributions help achieve the SDGs by 2030. To fulfill their social responsibilities, corporations must adapt themselves to the future needs and become more transparent about it [149]. SDGs can serve as a reliable agenda in a continuously changing and unpredictable business world. The SDG perspective is far broader and more forward-looking than individual corporations, making business both more socially responsible and sustainable. They foster mutual accountability and fulfill society’s expectations. In addition to contributing to the SDGs, businesses also shape them with their novel ideas and actions [150].

Since the SDGs contain an internationally-considered and accepted set of objectives, it starts where mutual interests meet. Hence, it is a reputable, comprehensive, and practical framework for CSR. It is also aligned with sustainability which benefits each entity including the corporation [150,151]. In what follows, three examples in the energy, food, and health industries illustrate the need to integrate CSR and SDGs.

4.1. The Energy Industry

CSR has highly been recognized by the energy industry [152]. Instead of traditional energy sources, it promotes renewable energy. Businesses invest in improving their energy security and efficiency, updating their technology and procedures, and minimizing the negative effects of energy storage and transport. Sustainable Energy Development (SED) goals aim to reduce pollution, increase efficiency, enhance alternative energy resources and utilize new technologies. In the meanwhile, energy supply sustainability is the guide to protect future needs while satisfying current requirements. CSR activities may lower the costs for consumers and encourage renewable energy and energy-saving technologies. In this matter, CSR is positively related to SED [2]. CSR elevates companies’ non-financial performance such as carbon footprint mitigation [153], economic development, and the avoidance of greenwashing [154,155].

4.2. The Food Industry

Another example is the food industry and food value chain (FVC) in which Social Sustainability (SS) and Social Responsibility (SR) play important roles. SS contains various dimensions including human rights, labor rights, food security, resources accessibility, and environment protection. In the meanwhile, SR is used to include social sustainability in corporations’ supply chain. Corporations, governments, NGOs, media, and the press have the power to raise awareness about SS and SR. SDGs require collective actions and encourage the participation of all formal and informal players and influencers who are decision makers in policy and science [149]. Customers on the other hand are sensitive to child and forced labor, slavery, injustice, and degraded working conditions. If they notice any inhuman behavior, it is likely they stop purchasing the product. However, in most cases, customers lack enough information to make such a decision which is why transparency is important. In addition to price, people need to know that the food they are buying respects the rights of all those involved in its production. Customers increasingly demand sustainable products [156] and will choose them if they have access to reliable and sufficient information about their production line [49]. Businesses have a decision to make that whether they are willing to make the investment in sustainable product development or they are willing to put their reputation at risk [157].

4.3. The Healthcare Industry

The last example is the healthcare industry where the network between patients, experts, scientists, suppliers, and organizations is the key element of social sustainability and sustainable healthcare [158]. Experts promote sustainability through collaboration, communication, and sharing knowledge [159]. CSR implementation, such as environmental pollutant control [160] in supply management, is in demand [161] and aids in sustainability maintenance.

Ethical principles and CSR implementation in healthcare institutions support sustainability [162]. Therefore, ethical principles, social responsibilities, and sustainability are complementary. Healthcare employees’ participation in CSR positively affects their innovation, which results in sustainability of innovation in the workplace [163,164]. The implementation of CSR improves employee quality of work and makes them more pro-environmental, especially when paired with ethical leadership in the corporation [165]. Furthermore, CSR is a risk management strategy as it protects firms’ reputations, keeps stakeholders satisfied, and builds trust among patients [166].

Those three examples discussed how CSR concerns elevate business sustainability. The better companies implement CSR, the more sustainable they become [167]. Unequal distribution of wealth, imbalanced population, ecological issues, unfair resource access are some challenges in today’s world. Sustainable Development and the SDGs encourage CSR policies to address such challenges. Stakeholder interests must align with society and the environment’s wellbeing. Corporate sustainability is achieved by integrating environmental protection, social empowerment, economic development, as well as stakeholder satisfaction and wealth creation.

Over the last two decades, the number of papers related to CSR and SDGs has increased dramatically. Researchers, institutions, and governments are all paying attention to sustainability and responsibility to emphasize the importance of these two regulation strategies [39].

But what is missing is an integrated implementation strategy. Based on their own limited information, each company contributes to one or a few of social issues and invests in the solution they find. The implementation budget could be reduced by further research costs. What if all companies implemented CSR plans through a comprehensive and measured framework designed by the most professional experts around the world? SDGs are the best fit for this argument. As a result, not only are all businesses contributing to the same purposes, but they are also using the plan that was introduced internationally by the world’s top experts (including top UN officials and heads of states) and is adopted and consistently developed by all 193 UN members to empower their societies and subsequently the entire world. Additionally, corporations spend less on research to find the best CSR plans since massive research has already been done in developing the SDGs and corporations access the results easily. Businesses decide how to contribute to the 17 goals based on their resources. We believe corporate CSR budgets could be better spent if they went to the SDGs. In the following section we explore all 17 SDGs and trace their long- and short term-direct impacts as well as their indirect effects. Furthermore, we offer a comprehensive framework for corporations to integrate their CSR strategies.

5. The Proposed Framework

CSR and SDGs are already being implemented separately in the business world. We suggest corporate CSR activities promote the SDGs. By 2030, the UN envisions a more sustainable, efficient, safe, and productive world. After many years of research, SDGs are designed by experts worldwide to fulfill this vision. They aim to strengthen the foundations of life on earth. We suggest corporations invest in the most urgent issues of their own societies using the SDGs.

In this section we purpose an integrated framework where we combine CSR and SDGs to: (1) help companies save their environment, society, and economy, and (2) earn more profit and develop their organizations. In this section, First, we propose our CSR framework based on the SDGs in Figure 3. Then we investigate environmental, social, and economic aspects of the SDGs and explain how each goal creates value for corporations.

Figure 3.

Proposed comprehensive framework for CSR implementation addressing SDGs’ contributions.

As shown in Figure 3 our CSR model is based on the SDGs. In Section 2 we looked at eleven drivers and eight benefits and created value of CSR for corporations. CSR implementations are divided into the environment, society, and economy based on Figure 2. In Section-3 we discussed the same divisions for the SDGs. In our model, we propose corporations use related SDGs in their implementation strategies which results in other eight benefits as introduced in Figure 3. The SDGs are designed to address both current and future needs. As such, they address both short- and long-term CSR visions. The SDGs include everyone from individuals to countries and the planet as a whole, therefore it covers all five scopes of CSR (Figure 2). All four CSR targets are met by the SDGs since they were designed by the UN to be in line with the wellbeing of everyone, prevent harm, and encourage voluntary actions to help others in a multidimensional and comprehensive manner.

The SDGs encourage international partnerships since investing in developing and underdeveloped countries benefits developed countries as well. In addition to causing poverty, poor health, and violence for locals, wars threaten the security of neighboring countries. War leads to unwanted immigration, destroys businesses, kills highly skilled human resources, reduces the labor force, and makes the Earth more unsafe. Future generations will be threatened by a lack of education. People in low-income countries can’t develop their societies because of poor health, poverty, and hunger. Companies invest in SDGs to protect themselves from future risks. SDGs, if implemented based on corporations’ actual priorities, result in business sustainability. It helps societies become more functional, avoid any economic instability, and environmental crisis. By empowering potential customers and employees, it also protects the companies’ natural resources and expands their customer and labor market. Therefore, it enables sustainable resource management. Figure-3 illustrates a list of the value created by the SDGs which impacts the entire planet including all internal and external CSR drivers.

Similar to CSR, SDGs are divided into environmental, social, and economic targets. We will take a look at each of the 17 goals of the Sustainable Development based on their divisions in the following subsections.

5.1. Environment

Air pollution [35,168,169], water pollution [170,171], soil and land pollution [172,173], global warming [174,175], climate change [176], ozone layer depletion [177], natural resource depletion [178], natural disasters [179], carbon footprint [180], deforestation [181], ocean acidification [182], loss of biodiversity [183], and overpopulation [184] are serious environmental issues. Considering the large number of existing companies, the impact of even their small actions on these issues are significant. During the last three decades, sustainable development and corporate environmental management have drawn attention to preserving the environment, and corporations are feeling increasing pressure from their stakeholders to be recognized as good corporate citizens [185]. Monitoring organizational performance requires an awareness of the environment [186]. On the other hand, Green growth requires corporations to reduce their environmental pollution and energy consumption [187]. This section examines environmental protection in CSR and SDGs scope. The following five goals of the SDGs concentrate on the world’s most urgent environmental issues [8].

SDG-6 (Clean Water and Sanitation): Water is one of the most precious resources on earth that is currently in short supply. Besides threatening biodiversity and ecosystems, desertification causes irreparable damage, such as water scarcity, poor sanitation, and a lack of drinking water. Water is not abundant. Water resource management, wastewater recycling, freshwater resource seeks, water-pollution control, water cost affordability, water quality, and sustainability are vital. SDG-6 sets a number of the most required and efficient ways to slow the water crisis down [188,189,190,191,192].

SDG-7(Affordable and clean energy): Global energy demand is rising [193,194,195]. The resources are not unlimited nor are they accessible to everyone. SDG-7 refers to fair access to energy for all. It calls for affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy. Affordable and clean energy is directly related to other SDGs [196]. Energy production enhancement, energy efficiency [197,198], alternative energy resources [199], modern and renewable energy [200], clean cooking [201,202], energy cost [203], and zero-carbon energy and green-house gasses [204] are just a few highlights of the SDG-7 literature.

SDG-13 (Climate Action): The Paris Agreement on climate change was signed by 195 countries to address global warming, the atmosphere temperature increase, the atmosphere carbon-dioxide concentration, carbon cycle, global emissions, and increased greenhouse gasses [205,206]. SDG-13 is the umbrella term. It suggests reducing climate change speed while recovering current environmental damage [207,208]. The SDG-13 is closely related to other SDGs. The climate impacts agriculture production, which affects poverty and hunger. Water, sanitation, sea level, energy resources, ocean acidification, and desertification are all affected by climate change. Thus, a lack of drinkable water unavoidably affects people’s health. People’s lives, businesses, and economies are corrupted by environmental changes which endanger the most vulnerable members of society first. At this point, inequality (race, gender, education, income) could also spread [209].

SDG-14 (life below water): SDG-14 focuses on sustainable ocean use, including reducing marine pollution, ocean acidification, overharvesting, and overfishing as well as protecting fresh and brackish water, animal diversity, and seafood for humans and animals as well as promoting ocean and sea transport. Ocean damage corrupts other SGDs and starts a cycle of global and local environmental, social, and specifically economic harms [210,211,212,213]. As an example, water pollution and overfishing change ocean biodiversity and reduce food production (i.e., reduce hunger); Seafood companies face difficulties doing business which affects their profitability and ultimately forces them to lay off their employees. Such consequences increase inequality since the most vulnerable people are the employees who lose their jobs. This cycle expands to almost all 17 goals.

SDG-15 (life on land): Human activities and climate change both trigger land and soil degradation [214]. Industrialization and urbanization are the two most important drivers of ecosystem degradation. Modern agriculture and population growth are other human-made factors [215]. These factors have always had business footprints. The road to extinction is wide open for all livings, including humankind.

5.2. Society

Social issues keep people from reaching their full potential, preventing a healthy lifestyle, and disrupting communities and corporations. Most of these issues are global, but some are specific to certain places or groups of people. Some examples would be discriminations (race, color, and gender), poverty [216], homelessness [217], hunger [218], malnutrition and obesity [219], drug and alcohol addiction [220], depression, anxiety and mental health problems [221], lack of minimum rights and freedom [222], unemployment crisis [223], pandemics and epidemics [224], disabilities and chronic diseases, violence, crime, and insecurity as well as wars and political conflicts [225], gender inequality [226], lack of education and opportunities [227]. Here we discuss four goals that directly address social issues of the world which could be at the top of corporations’ CSR plans.

SDG-1 (No Poverty), SDG-2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG-3 (Good Health and Well-being): Basic needs are compromised by hunger, poverty, and poor health while they form a circle. Poverty ends in malnutrition and hunger [228], lack of quality food triggers poor health [229], and poor health decreases functionality. Those who are not productive cannot make ends meet. People, societies, and countries living in poverty struggle with the fundamentals of life and never develop. Lacking proper education, they lack the skills, knowledge, and abilities needed for higher paying jobs. And they are a burden rather than a help to their societies. Many talented people around the world never fulfill their potential because of financial, food, or health issues. If this is not a loss for corporations (as employers), then whose is it? These people could be both the businesses’ helpful employees and their potential customers [230]. As an example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many businesses went bankrupt, and many people lost their jobs, their health, or family members. Companies can help resolve this crisis, so that everyone return to how they used to function and corporations can continue to operate as usual [231,232,233].

SDG-4 (Quality Education), SDG-5 (Gender Equality) and SDG-10 (Reduce Inequality): Education elevates people’s knowledge, skills, and abilities, makes them better employees, creates more aware customers, and makes companies’ market segments more uniform, which consequently, saves them a lot of marketing and production diversity costs. Differences such as race, gender, and education do not make individuals different or restrict their human rights. Equal opportunities provide people with better chances of improvement. The equitable expansion of society and development of the potential of all people is to the benefit of corporations, since these people are their potential customers and employees.

SDG-11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities): Wealth, employment, and innovations are created in cities. Over 80 percent of the world’s GDP is produced in cities [234]. Cities comprise a huge population of both customers and employees. SDG-11 suggests everyone should have access to, at least, basic housing and transportation facilities; It recommends three-dimensional links between urban and rural areas to collaborate socially, share natural resources, and develop business partnerships [235]. Culture on the other hand, is what unites people. Promoting local cultures makes societies uniform and makes it easier for businesses to navigate their market. It is beneficial for corporations to learn about local cultures [236]. This knowledge helps them create organizational culture or even write marketing strategies [237]. Powerful cities empower corporations. Therefore, investing in SDG-11 is not just a philanthropic investment. It is a financial one [238].

SDG-12 (Ensure Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns): Resources are limited. Recycling technologies reduce natural resource extraction, but they cannot completely replace them. Based on the Resource Dependence Theory (Reitz, 1979), corporations’ future depends on natural resources. Besides the energy and facilities used for production, pollution and hazardous waste control and the recycling process costs are extremely high [239]. Natural resource management, waste control [240], reuse and recycle technologies [241], product life cycle development [242], and food loss reduction [243] are examples that relate to the SDG-12 and can help corporations reduce their environmental and social damages [244,245].

Circular economy is closely related to sustainability [157,246]. CE is concerned with resource efficiency, water and energy recovery, waste and emissions reduction, intelligent use of materials and manufacturing technology, and extended product life; CE protects the environment, benefits society and economy, and directly contributes to sustainability [247,248,249]. We believe, CSR and CE are completely in line with sustainable production and consumption and can be interchangeably used.

Capitalism drives consumerism [250]. Sustainable marketing strategies adopt a different approach from making more profit by selling more to taking into account the long-term impacts of overconsumption by changing their own behavior and that of their customers. Mindfulness, consciousness, and awareness can result in sustainable consumption behavior [251,252,253] People are sensitive to environmental issues, sustainable consumption, and social responsibility awareness [254]. If consumers are informed of the issue and given ideas on how to contribute, they will consider it. Food labels, for example, allow consumers to know more about the products they are using and organize their sustainable consumption [255]. Therefore, raising awareness about sustainable consumption, sustainable production, and green consumerism [256] has a positive impact on society and is recognized as a socially responsible action, simultaneously promotes the SDGs.

SDG-16 (Peace and Justice Strong Institutions): Obviously, peace is a fundamental desire of human beings and societies. Companies depend on humans from natural resource extraction to production and distribution labor, and more importantly, customers. By investing in the security of their stakeholders, companies are, in fact, directly investing in their own development. That is one way to look at businesses’ contribution to SDG-16. The power of corporations lies in raising awareness [257] or investing in direct approaches based on their circumstances. To make the world a safer place, it is vital to reduce violence, such as wars, human trafficking, abuse, and injustice, and to promote basic freedom, legal identity, and non-discrimination laws [258,259,260,261].

5.3. Economy

Companies depend on the economy they operate in. Business becomes more predictable and functional as their economy gets stable. We suggest corporations dedicate part of their CSR budget to at least one of the following goals.

SDG-8 (Decent work and economic growth): Economic growth could easily affect business strategies implementation. whoever promotes SDG-8 is working in favor of corporations. The United Nations has specifically designed this goal for businesses and employees. SDG-8 concentrates on fair and conventional trade, stable and even-handed prices, decent work conditions [262], domestic production support, small businesses and local enterprises, creativity and innovation, global economic growth, controlled consumption, resource management, equal and full employment, slavery and forced labor eradication, and adequate access to financial services [8,262,263]. To succeed in the long-term, corporations make socially responsible short-term decisions. The more they grow their economy, the more their share of it will value.

SDG-9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) and SDG-17 (Partnerships to achieve the Goal): SDGs suggest industries should be equipped with an innovative, reliable, and strong economy, management, and sustainable infrastructures, but also should update their resource consumption and extraction procedures. Knowledge management and raising awareness significantly impacts the corporations’ functionality and the practice of all three SDGs dimensions, especially corporate green innovation [264]. In addition, companies should seek more cooperation and partnership to meet the increasing demand for sustainability [265]. Governments play an important role especially when it comes to policies and regulations. Innovation and infrastructure combined with sustainable industrialization can result in a dynamic and competitive economy that generates employment and revenue CSR budgets could be allocated to new sectors such as knowledge-based firms, emerging industries, convergent technologies, and biotechnology and nanotechnology firms.

SDG-9 helps developing and underdeveloped countries grow, become sustainable, update their industries, increase domestic production, access more communication facilities, increase industry diversity and added value, enable flexible development, facilitate change management, and find better ways to pay their debts and loans [8]. It also suggests business partnerships and collaborations between developed and developing countries to create win-win strategies. Resources and labor costs in developing and underdeveloped countries are lower than in developed countries. Several parts of corporations’ research and development activities, production, and service can be outsourced to deprived areas to lower production costs and create opportunities for deprived societies and increase economic and employment opportunities for the locals. Global businesses and poor countries can cooperate and have mutual interests in many ways. Such strategies benefit both CSR and SDGs. SDG-17 completes all previous 17 goals and closes the circle of Sustainable Development agenda [266,267,268].

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the world was not in a good place. United Nations’ 17 goals are far from being achieved and many will not be accomplished by 2030. Besides money, corporations have facilities, technologies, and knowledge to contribute to the SDGs. Businesses rely on natural resources accessibility, workforce functionality, economy reliability, and customer purchase. They cannot operate in corrupt societies, economies, and environments. The more sustainable our planet becomes, the more sustainable businesses become. To achieve sustainable societies, public health, life-long education, economic stability, crisis management, poverty reduction, and environmental protection, corporations can pool their skills, knowledge, and resources. In this study we highlighted how corporations can promote sustainability and peruse their CSR financial and non-financial purposes through the SDGs.

6. Conclusions

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is driven by stakeholders, shareholders, board of directors, managers, employees, customers, competitors, governments, industries, NGOs, and the media. CSR benefits corporations in many ways, such as financial performance, identification and image, reputation, brand, public trust, customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, and purchase intention. Meanwhile, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) result in business sustainability, stable economies, functional societies, crisis prevention, resource management, labor market expansion, and universal market growth. CSR and SDGs are complementary since they both promote environmental protection and socioeconomic development. SDGs help corporations achieve CSR goals since globally, they are more comprehensive. SDGs are holistic and interconnected, meaning that promoting one goal can support others. SDGs results last longer; therefore, they save companies time and money. Corporations reduce CSR research costs and focus on the most rewarding contributions when they use the SDGs. The SDGs affect CSR drivers in many ways and improve their quality of life, keeping them satisfied with corporations’ performance. The SDGs provide corporations with a framework for CSR that reflects their present and projected needs.

This study presents a comprehensive CSR model and a new CSR drivers model. Then, it highlights the advantages of CSR and SDGs. Finally, it recommends that enterprises should make use of the SDGs as a framework to enhance their CSR practices. The proposed framework benefits from both CSR and SDGs, addresses current and future needs, and offers a roadmap with more measurable outcomes.

This study’s limitations are linked to the broadness of the matter which is worldwide. Almost all aspects of the SDGs and CSR have many different inputs, outputs, and parameters at the industrial, national, and international levels. Therefore, future studies should be more detailed and localized, or at least should focus on specific countries, industries, or companies. Analytical and empirical studies can result in managerial and more practical and detailed strategies. The study offers a new perspective by suggesting that SDGs be used as a framework for CSR implementations and discusses how beneficial this framework is. As it is only the beginning of further studies, and more research is needed to determine which goals and targets are advantageous to specific corporations based on their country of origin, industry, business characteristics, etc. Resources and purposes of corporations ultimately determine how CSR plans can be integrated with the SDGs. Another approach would be to lay out a comprehensive list of SDGs’ targets, categorized by all 17 goals, that businesses can contribute to and profit from the most. Further studies should prioritize the SDGs and their targets according to the most urgent local and global issues and the most rewarding CSR strategies. The managerial actions at this point would be to identify potential targets of the SDGs that could become the objective of the corporations’ CSR activities. The combination of managerial implications with empirical and analytical research is expected to result in a more advanced and practical framework in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.F.S. and M.A.Z.; Funding acquisition, N.M.-K.; Supervision, N.M.-K., S.A. and M.A.Z.; Writing—original draft, N.F.S.; Writing—review & editing, N.M.-K., S.A. and M.A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study does not report any data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our special thanks of gratitude to Montgomery Van Wart, Professor of Public Administration and the University Faculty Research Fellow at California State University, San Bernardino, for his invaluable guidance and feedback to improve the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yadav, S.; Bhudhiraja, D.; Gupta, D. Corporate Social Responsibility–The Reflex of Science and Sustainability. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2021, 7, 6222–6233. [Google Scholar]

- Tiep, L.T.; Huan, N.Q.; Hong, T. Role of corporate social responsibility in sustainable energy development in emerging economy. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2021, 11, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Grewatsch, S.; Sharma, G. How COVID-19 informs business sustainability research: It’s time for a systems perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apedo-Amah, M.C.; Avdiu, B.; Cirera, X.; Cruz, M.; Davies, E.; Grover, A.; Iacovone, L.; Kilinc, U.; Medvedev, D.; Maduko, F.O. Unmasking the Impact of COVID-19 on Businesses: Firm Level Evidence from Across the World. Policy Res. Work. Pap. 2020, 9434. [Google Scholar]

- Bartik, A.W.; Bertrand, M.; Cullen, Z.B.; Glaeser, E.L.; Luca, M.; Stanton, C.T. How Are Small Businesses Adjusting to COVID-19? Early Evidence from a Survey; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, T.H.; Judge, K. How to help small businesses survive COVID-19. In Columbia Law and Economics Working Paper; Stanford Law School: Stanford, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Popkova, E.; DeLo, P.; Sergi, B.S. Corporate social responsibility amid social distancing during the COVID-19 crisis: BRICS vs. OECD countries. In Res. Int. Bus. Financ.; 2021; Volume 55, p. 101315. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. The sustainable development goals and business. Int. J. Sales Retail. Mark. 2016, 5, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Project, I.M. Statement of Intent to Work Together towards Comprehensive Corporate Reporting. Available online: https://www.integratedreporting.org/resource/statement-of-intent-to-work-together-towards-comprehensive-corporate-reporting/ (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tong, L.; Takeuchi, R.; George, G. Corporate social responsibility: An overview and new research directions: Thematic issue on corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, M.; Magnan, G.M.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R. Understanding the conceptual evolutionary path and theoretical underpinnings of corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability. Sustainable 2020, 12, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A.; Sheehy, B. Corporate Citizenship. In Encyclopedia of Sustainable Management; Idowu, S., René, S., Capaldi, N., Zu, L., Del Baldo, M., Abreu, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Varzaru, A.; Bocean, C.; Nicolescu, M. Rethinking Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability in Light of Economic Performance. Sustainable 2021, 13, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Amar, W.; Francoeur, C.; Marsat, S.; Sijamic Wahid, A. How do firms achieve corporate social performance? An integrated perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1078–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatmawati, I.; Fauzan, N. Building customer trust through corporate social responsibility: The Effects of corporate reputation and word of mouth. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 793–805. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Ponnapalli, A.R. Corporate social responsibility and corporate reputation: The moderating roles of CEO and state political ideologies. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Festa, G.; Chouaibi, S.; Fait, M.; Papa, A. The effects of business ethics and corporate social responsibility on intellectual capital voluntary disclosure. J. Intellect. Cap. 2021, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boodoo, M.U.; Henriques, I.; Husted, B.W. Putting the “Love of Humanity” Back in Corporate Philanthropy: The Case of Health Grants by Corporate Foundations. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 175, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Harris, L. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; García-Sánchez, A. Corporate social responsibility during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.-H.; El Ghoul, S.; Gong, Z.J.; Guedhami, O. Does CSR matter in times of crisis? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 67, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.C.; Jiang, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, M.-H.; Yuan, X. Can corporate social responsibility protect firm value during the COVID-19 pandemic? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante Antwi, H.; Zhou, L.; Xu, X.; Mustafa, T. Beyond COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrative Review of Global Health Crisis Influencing the Evolution and Practice of Corporate Social Responsibility. Healthcare 2021, 9, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. COVID-19 and the future of CSR research. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 58, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the COVID-19 pandemic: Organizational and managerial implications. J. Strategy Manag. 2021, 14, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Pekyi, G.D.; Chen, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, X. Sustainability-Conscious Stakeholders and CSR: Evidence from IJVs of Ghana. Sustainable 2021, 13, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Dong, H.; Lin, C. Institutional shareholders and corporate social responsibility. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 135, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Fang, L.; Zhang, K. How Foreign Institutional Shareholders’ Religious Beliefs Affect Corporate Social Performance? J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 175, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumiati, S.; Sueztianingrum, R. The Role of CSR on Shareholders Wealth Through Intellectual Capital. In Proceedings of the 17 th International Symposium on Management (INSYMA 2020), Vung Tau City, Vietnam, 19–21 February 2020; Atlantis Press: Vung Tau City, Vietnam, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pekovic, S.; Vogt, S. The fit between corporate social responsibility and corporate governance: The impact on a firm’s financial performance. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 15, 1095–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouber, H. Is the effect of board diversity on CSR diverse? New insights from one-tier vs two-tier corporate board models. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 21, 23–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setó-Pamies, D. The relationship between women directors and corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Tan, J.; Chan, K.C. Seeing is believing? The impact of air pollution on corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Shen, R.; Tang, T.; Yan, X. Horizon to Sustainability: Uncover the Instrumental Nature of Corporate Social Responsibility. 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3791167 (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- AN, S.B.; YOON, K.C. The Effects of Socially Responsible Activities on Management Performance of Internationally Diversified Firms: Evidence from the KOSPI Market. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Voica, M.C.; Stancu, A. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: Background, Evolution and Sustainability Promoter. In Sustainable Management for Managers and Engineers; Machado, C.F., Davim, J.P., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 109–155. [Google Scholar]

- Meseguer-Sánchez, V.; Gálvez-Sánchez, F.J.; López-Martínez, G.; Molina-Moreno, V. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability. A Bibliometric Analysis of Their Interrelations. Sustainable 2021, 13, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoleni, M.; Paredi, D.; Tonoli, D. How to Meet Stakeholders’ Expectations on Environmental Issues? An Analysis of Environmental Disclosure in State-Owned Enterprises via Facebook. Glob. Media J. 2021, 19, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, Y. Stakeholders expectations for CSR-related corporate governance disclosure: Evidence from a developing country. Asian Rev. Account. 2021, 29, 97–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Basile, K. Communicating Corporate Social Responsibility: External Stakeholder Involvement, Productivity and Firm Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 175, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Sial, M.S.; Ahmad, N.; Sehleanu, M.; Li, Z.; Zia-Ud-Din, M.; Badulescu, D. CSR as a potential motivator to shape employees’ view towards nature for a sustainable workplace environment. Sustainable 2021, 13, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvis, P. Employee engagement and CSR: Transactional, relational, and developmental aroaches. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2012, 54, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J.; Kim, B.-J. The Performance Implication of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Role of Employee’s Prosocial Motivation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murshed, F.; Sen, S.; Savitskie, K.; Xu, H. CSR and job satisfaction: Role of CSR importance to employee and procedural justice. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2021, 29, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharalampous, N.; Papadimitriou, D. Perceived corporate social responsibility and affective commitment: The mediating role of psychological capital and the impact of employee participation. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2021, 32, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Linking internal CSR with the positive communicative behaviors of employees: The role of social exchange relationships and employee engagement. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, M.; Cabanelas, P.; González-Alvarado, T.E. What about the consumer choice? The influence of social sustainability on consumer’s purchasing behavior in the Food Value Chain. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaveli, N. Two countries, two stories of CSR, customer trust and advocacy attitudes and behaviors? A study in the Greek and Bulgarian telecommunication sectors. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2021, 18, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.; Shanmugam, M. The impact of corporate social responsibility on word-of-mouth through the effects of customer trust and customer commitment in a serial multiple mediator model. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2021, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceciliano, P.H.; da Costa Vieira, P.R.; da Silva, A.C.M. The influence of corporate social responsibility on corporate brand equity: A study with structural equation modeling. Indep. J. Manag. Prod. 2021, 12, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, K.G.; Harun, A.; Hamawandy, N.M.; Qader, K.S.; Jamil, D.A.; Jalal, F.B.; Sorguli, S.H. Corporate Social Responsibility Activities Factors and Their Affecting on Maintaining Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in Hypermarket Industry in Malaysia. J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Gov. 2021, 27, 1090–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in developed and developing countries: A literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Chan, H.-L.; Dong, C. Impacts of competition between buying firms on corporate social responsibility efforts: Does competition do more harm than good? Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 140, 101985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Chen, S.; Elahi, E.; Wan, A. Can corporate environmental responsibility improve environmental performance? An inter-temporal analysis of Chinese chemical companies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yi, X.; Shi, W.; Zhang, D. Do CSR Awards Motivate Award Winners’ Competitors to Undertake CSR Activities? In Academy of Management Proceedings, Chicago, IL, USA, 10–14 August 2018; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Chen, X.; Li, A.; Xia, X. Disclosure for whom? Government involvement, CSR disclosure and firm value. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2020, 44, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zueva, A.; Fairbrass, J. Politicising Government Engagement with Corporate Social Responsibility:“CSR” as an Empty Signifier. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 170, 635–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Li, S.; Wu, H.; Song, X. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: The roles of government intervention and market competition. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yi, Y. The Manufacturer Decision Analysis for Corporate Social Responsibility under Government Subsidy. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6617625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Long, X.; Schuler, D.A.; Luo, H.; Zhao, X. External corporate social responsibility and labor productivity: AS-curve relationship and the moderating role of internal CSR and government subsidy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Yan, Y.; Yao, F. Closed-loop suly chain models considering government subsidy and corporate social responsibility investment. Sustainable 2020, 12, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q. Government Subsidy Policies and Corporate Social Responsibility. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 112814–112826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Miao, Z. Corporate social responsibility and collaborative innovation: The role of government suort. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadjib, A.; Zainal, R.I. Integrating Business CSR With Local Government Development Program: Business Perception. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2020, 10, 108122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, M. Corporate Social Responsibility in Australia. In Sovereign Wealth Funds, Local Content Policies and CSR: Developments in the Extractives Sector; Pereira, E.G., Spencer, R., Moses, J.W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 601–619. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Yu, S.; Huang, X.; Tu, X.; Hong, J. Study on Equilibrium Relationship Between Government Regulation and Social Environmental Responsibility of Energy Enterprises. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Kamakura City, Japan, 10–11 October 2020; IOP Publishing: Bristo, UK, 2021; p. 032028. [Google Scholar]

- Koseoglu, M.A.; Uyar, A.; Kilic, M.; Kuzey, C.; Karaman, A.S. Exploring the connections among CSR performance, reporting, and external assurance: Evidence from the hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A.; Hikmat, I.; Haquei, F.; Badariah, E. The Influence of Share Ownership, Funding Decisions, Csr and Financial Performance of Food Industry. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 12698–12710. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyar, M.N.; Ali, F.; Shafique, I. Green mindfulness and green creativity nexus in hospitality industry: Examining the effects of green process engagement and CSR. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 2653–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, P. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) website disclosures: Empirical evidence from the German banking industry. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 768–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelikánová, R.M.; Němečková, T.; MacGregor, R.K. CSR Statements in International and Czech Luxury Fashion Industry at the Onset and during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Slowing Down the Fast Fashion Business? Sustainable 2021, 13, 3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibenrissoul, A.; Kammoun, S.; Tazi, A. The Integration of CSR Practices in the Investment Decision: Evidence From Moroccan Companies in the Mining Industry. In Adapting and Mitigating Environmental, Social, and Governance Risk in Business; Ziolo, M., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 256–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kvasničková Stanislavská, L.; Pilař, L.; Margarisová, K.; Kvasnička, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and Social Media: Comparison between Developing and Developed Countries. Sustainable 2020, 12, 5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troise, C.; Camilleri, M.A. The use of digital media for marketing, CSR communication and stakeholder engagement. In Strategic Corporate Communication in the Digital Age; Camilleri, M.A., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, N. Unit-3 Role of CBOs and NGOs in Driving CSR Initiatives. In Block-2 Implementation Partnership; Indira Gandhi National Open University: New Delhi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Hermes, N.; Hooghiemstra, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and NGO Directors on Boards. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 175, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Sidhoum, A.; Serra, T. Corporate sustainable development. Revisiting the relationship between corporate social responsibility dimensions. Sustainable Dev. 2018, 26, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, T.H. Strategic CSR communication: A moderating role of transparency in trust building. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2018, 12, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Ha, M.H. Corporate social responsibility and earnings transparency: Evidence from Korea. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1498–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, S. Value creation model through corporate social responsibility (CSR). Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 6, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juscius, V.; Jonikas, D. Integration of CSR into value creation chain: Conceptual framework. Eng. Econ. 2013, 24, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T. Corporate social responsibility: A value-creation strategy to engage millennials. Strateg. Dir. 2019, 35, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolo, M.; Filipiak, B.Z.; Tundys, B. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Value Creation. In Sustainability in Bank and Corporate Business Models; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 67–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jahmane, A.; Gaies, B. Corporate social responsibility, financial instability and corporate financial performance: Linear, non-linear and spillover effects–The case of the CAC 40 companies. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 34, 101483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najihah, N.; Indriastuti, M.; Suhendi, C. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Cost on Financial Performance. In Complex, Intelligent and Software Intensive Systems. CISIS 2020. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Barolli, L., Poniszewska-Maranda, A., Enokido, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1194, pp. 418–425. [Google Scholar]

- Okafor, A.; Adusei, M.; Adeleye, B.N. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Evidence from US tech firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 126078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Naeem, H.; Aftab, I.; Mughal, S.A. From corporate social responsibility activities to financial performance: Role of innovation and competitive advantage. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2021, 15, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Investigating the effects of corporate social responsibility on financial performance. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Guilin, China, 26–28 March 2021; IOP Publishing: Guilin, China, 2021; p. 012068. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The effect of CSR on corporate image, customer citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartini, C.A.A.; Pertiwi, I.F.P. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Consumer Purchase Decisions with Corporate Image and Brand Image as Intervening. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2021, 2, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Pham, T.; Le, Q.; Bui, T. Impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment through organizational trust and organizational identification. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 3453–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, P.; Kar, A.K.; Ilavarasan, P.V. Impact of corporate social responsibility on reputation—Insights from tweets on sustainable development goals by CEOs. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.E. Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Management in Telecommunication Industries in Bayelsa State, Nigeria. J. Int. Relat. Secur. Econ. Stud. 2021, 1, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Singh, J.J. Co-creation: A key link between corporate social responsibility, customer trust, and customer loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, F.; Swaen, V.; De Roeck, K. Coporate branding and corporate social responsibility: Toward a multi-stakeholder interpretive perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Torné, I.; Morán-Álvarez, J.C.; Pérez-López, J.A. The importance of corporate social responsibility in achieving high corporate reputation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2692–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Zayyad, H.M.; Obeidat, Z.M.; Alshurideh, M.T.; Abuhashesh, M.; Maqableh, M.; Masa’deh, R.E. Corporate social responsibility and patronage intentions: The mediating effect of brand credibility. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 27, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Chatterjee, M.; Bhattacharjee, T. Does CSR disclosure enhance corporate brand performance in emerging economy? Evidence from India. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2021, 13, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Nawaz, N.; Alfalah, A.A.; Naveed, R.T.; Muneer, S.; Ahmad, N. The Relationship of CSR Communication on Social Media with Consumer Purchase Intention and Brand Admiration. J. Theor. Alied Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1217–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacap, J.P.G.; Cham, T.-H.; Lim, X.-J. The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Loyalty and The Mediating Effects of Brand Satisfaction and Perceived Quality. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2021, 15, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N.; Naveed, R.T.; Scholz, M.; Irfan, M.; Usman, M.; Ahmad, I. CSR communication through social media: A litmus test for banking consumers’ loyalty. Sustainable 2021, 13, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatane, S.E.; Pranoto, A.N.; Tarigan, J.; Susilo, J.A.; Christianto, A.J. The CSR Performance and Earning Management Practice on the Market Value of Conventional Banks in Indonesia. In Global Challenges and Strategic Disruptors in Asian Businesses and Economies; de Pablos, P.O., Lytras, M.D., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 196–213. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wan, P. Social trust and corporate social responsibility: Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Pervan, S. Retailer corporate social responsibility and consumer citizenship behavior: The mediating roles of perceived consumer effectiveness and consumer trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102082. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.Y.; Danish, R.Q.; Asrar-ul-Haq, M. How corporate social responsibility boosts firm financial performance: The mediating role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, K.B.; Jusoh, A.; Nor, K.M. Relationships and impacts of perceived CSR, service quality, customer satisfaction and consumer rights awareness. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 17, 1116–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Islam, R.; Pitafi, A.H.; Xiaobei, L.; Rehmani, M.; Irfan, M.; Mubarak, M.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer loyalty: The mediating role of corporate reputation, customer satisfaction, and trust. Sustainable Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]