Abstract

The article presents an extension of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) to identify, in a Latin American university, the students who are children of entrepreneurial parents and the determinants of their willingness to succeed them. The TPB is used as a basis to analyse the intention to be a successor, and three constructs are added: affective commitment, normative commitment and parental role model. The analysis is carried out using structural equations via the partial least squares (PLS) method, which allows for the study of multiple relationships between construct-type variables. The sample includes 16,185 Latin American university students from the Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students’ Survey 2018 database. The results show that, in Latin American students, the determining factors in the intention to be a successor are attitude, the affective and normative commitment and the parental role model. The latter has a negative and significant effect on the intention to be a successor in the family business. One of the practical implications of this study has to do with the development of an affective feeling of the offspring towards the family business. Generating this kind of attachment since childhood could lead to achieving a greater relevance of the parental role model and a stronger interest in the succession of the business.

1. Introduction

In the literature on entrepreneurship, and particularly on university entrepreneurship, the studies are predominantly oriented towards identifying the factors that influence young people’s intention to become entrepreneurs [1,2,3]. It is known in research on entrepreneurship that intention plays a key role. Intention has proven to be the best predictor of planned behaviour, particularly when the behaviour in question is “rare, hard to observe, or involves unpredictable time lags” [4] (p. 411), characteristics that certainly apply to entrepreneurship. A subject that is not much addressed in this literature or in the family business literature is the intention of young people to become the successors of their parents’ businesses. Birley [5] (p. 8) mentions that “there are no instruments in the literature dealing with that particular subject, only a number of statements about, for instance, the early involvement of children in their parents’ business as a way of training for succession or the retirement of the previous generation”.

Succession in companies is a topic widely discussed in the field of family businesses [6,7,8,9]; empirical evidence shows that close to one-third of family businesses pass to a second generation and a smaller percentage continue on to a third generation or beyond [10,11]. This lack of intergenerational succession can lead to discontinuity in company governance, which can lower performance or cause the failure of the business [12]. Some authors [13] even refer to the existence of a succession crisis in family businesses.

The few studies that have addressed the issue of successor intention in students with entrepreneurial parents have done so from the perspective of intention in career choice, that is, analysing the factors that determine the career choice intention of becoming an employee, successor or entrepreneur [14,15,16]. Only the study of Gimenez-Jimenez et al. [12] analyses the intention to become a successor among university students from an intergenerational perspective, using Global University Spirit Students’ Survey (GUESSS) data. The results of these studies are not very conclusive and are focused on developed countries, particularly European countries, among others. No studies have been identified on the succession intentions of students in emerging countries, such as those in Latin America [17]. In these countries, a significant proportion of children of entrepreneur parents are the first generation of their families to go to university. Family businesses in Latin America represent between 70% and 92% of the business sector and account for about 70% of the GDP of their respective countries and 70% of employment [18]. As a result, these businesses are fundamental for the development of the continent. According to [19], less than 15% of these companies are managed by a third-generation member, and close to two thirds of them will be sold by their owners or will go bankrupt. On this basis, two crucial challenges for these businesses are to maintain their competitiveness and address the problem of succession [20].

There is a gap in the literature on university entrepreneurship and family businesses associated with the determinants of the succession intentions of students with entrepreneur parents in emerging countries such as those in Latin America, a region characterized by a dominant presence of informal enterprises [21], where most do not have a clear succession strategy [22]. This study contributes to reducing this gap in knowledge and aims to identify the determinants of the intention to become a successor among Latin American university students with entrepreneur parents. To this end, Ajzen’s Planned Behaviour Theory (TPB) [23] was used as a basis to analyse the intention to become a successor of Latin American students. TPB is designed to predict and explain human behaviour in a specific context and has been empirically tested to effectively explain entrepreneurial intention as well as behaviour [24,25,26]. This theory consists of the three constructs that are considered predictors of the intention towards a certain behaviour: attitude towards behaviour (ATB), social factor, called subjective norms (SN), and perceived behavioural control (PBC).

Ajzen’s TPB also accepts that the model can be extended to include other factors, provided that their relevance is justified [24]. Three factors have been added to the Ajzen model in this study: the first two are related to commitment, a force that is experienced as a mindset or psychological state that drives a person towards a certain relevant goal [27] and is a relevant factor for business succession in the family business literature [28]. These two types of commitment are affective (desire-based) and normative (obligation-based) commitment [6]. When there is commitment by family members, there is a higher probability that the children will have the intention to continue with the succession [28,29]. The third factor is the parental role model, which comes from Bandura’s social learning theory [30,31] and is considered to be the most prominent factor that influences the choice to become an entrepreneur [32]. Children with entrepreneur parents are constantly exposed to the behaviour of their parents, starting with their early socialization, where the parents not only transmit information but also beliefs, social values, habits, attitudes and resources [33,34]. The behaviour that children observe and learn from their parents affects their development and their career intentions [33,34,35].

It is important to recognize that there are several family issues that could influence succession intention, such as genetics [36], birth order, intergenerational relationships [12,37,38], the structure of the family and the surroundings [34], among others. However, in this study, we used the Ajzen model as a starting point and extended it, considering that it is one of the most well-known and accepted models in the scientific community for studies on intention regarding specific behaviour.

The analysis was performed using structural equations based on a sample of 16,185 Latin American university students from the GUESSS 2018 database.

Our study contributes to a better understanding of and extends Ajzen’s [23] TPB model, contributing new evidence on the determinants of succession intentions of university students in Latin America with entrepreneur parents. Furthermore, the study also contributes to a better understanding of Bandura’s social learning theory [30,31], where empirical evidence predominates over the positive effect of the parental role model on the intention to become an entrepreneur [39]. This study provides new evidence on the negative effect of the parental role model on the succession intentions of Latin American students with entrepreneur parents and contributes to the debate on this subject in the scientific community. Thirdly, this study contributes to expanding knowledge on the relevance of commitment as a multidimensional variable in the succession intention in family businesses. Commitment has usually been treated as a one-dimensional variable; however, this study follows the guidelines of [6], analysing the two dimensions that have shown the greatest impact in the literature on organisational behaviour in family businesses: affective and normative commitment. Finally, our study contributes to the literature on university entrepreneurship and family businesses, with empirical evidence on the determinants of the succession intentions of Latin American students with entrepreneur parents, in a context where a significant number of these students are the first generation of their family to go to university.

The paper is structured as follows: the first section describes the theoretical framework, including the hypotheses. Next comes the methodology, followed by the results. Finally, the discussion and conclusions of the study are presented with the practical implications, limitations and future lines of research.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Theory of the Planned Behaviour (TPB) and the Intention to Be a Successor

To analyse the intention to become a successor, we draw on Ajzen’s [23] TPB. This theory postulates three determinants of intention that are conceptually independent. The first, ATB, refers to the degree to which a person has a favourable or unfavourable view of the behaviour in question, in this case, becoming a successor. The second predictor is a social factor called SN; it refers to the perceived social pressure to develop the behaviour or not. In this case, it would be the social pressure, from relatives and/or friends, perceived by the students to be a successor. In other words, “subjective norms are a situational (or exogenous) factor” [3] (p. 290). The third predictor is the degree PBC, which relates to the perceived ease or difficulty to develop the behaviour. It is assumed that it reflects both experience and perceived future obstacles.

Numerous studies have widely used this theory to examine the intention towards a behaviour in diverse fields, such as education, to analyse the intention to include handicapped students [40]. It has been used in health care, to predict reactions to therapies and risk to addictions [41], in workplace harassment [42] and in marketing, to study and predict purchasing intentions by consumers [43]. In general, there is ample empirical evidence from diverse areas confirming that the factors that constitute the TPB—attitude, SN and PBC—are relevant for the analysis of some future behaviour, with results that are mostly consistent. In the field of entrepreneurship, the evidence has shown that the best predictor of entrepreneurial intention has been attitude towards entrepreneurship, followed by PBC. The subjective norms have had mixed results: in some studies, they have been significant [44,45,46], whereas, in others, they have not had any relevance as a determinant of entrepreneurial intention [4,47,48]. Given this discrepancy, authors such as [49] show the indirect effect of the SN on the entrepreneurial intention through the attitude towards entrepreneurship and the PBC.

On the other hand, studies on the intention to be a successor based on Ajzen’s [23] model are quite scarce. The few works found in this field are focused on university students from developed countries, particularly European countries, and their results are also mixed. An outstanding work among these is [14], which resorts to two of the constructs of Ajzen’s [23] model to examine how the levels of attitude towards behaviour and perceived behavioural control and affect the probability of becoming a successor, an entrepreneur or self-employed. They do not consider subjective norms. Zellweger and Sieger [50], using Ajzen’s constructs, among others, analyse the determinants of intention to be a successor in students with family business background from 26 countries, including Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. Their results show that the intention to succeed is affected in a positive and significant way by attitude and subjective norms, and in a negative and significant way by PBC (self-efficacy). Ljubotina et al. [16] obtain quite different results when using the three constructs of Ajzen’s [23] model in their study of the trilemma faced by students with family business backgrounds in European countries with market and transition economies. According to them [16], the intention to succeed is also influenced by factors such as the country’s type of economy.

Since there is not enough empirical evidence on the intention to be a successor, especially among Latin American students, and considering that Ajzen’s model is consistent in the prediction of a given behaviour, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

The attitude towards succession has a direct and significant relation with the intention to be a successor.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

The perceived behavioural control has a direct and significant relation with intention to be a successor.

Hypothesis 1c (H1c).

The subjective norms have a direct and significant relation with intention to be a successor.

It is important to stress that Ajzen [23] himself points out that his model could be expanded to incorporate other variables, provided that their relevance can be justified and tested. Along those lines, this study adds three variables to Ajzen’s traditional model: affective commitment, normative commitment and parental role model, as explained in the sections below.

2.2. Commitment and Intention to Become a Successor

Commitment appears in the literature on family entrepreneurship as a relevant factor within the succession process in family businesses. In fact, research results show that committed family members are more likely to follow a career in their family business [27,28]. Gilding [51] suggests that family business owners who wish to keep the business in their family should strengthen the commitment of the next generation of family members to their business and, thus, encourage them to pursue a career in these businesses and ensure positive results.

According to Meyer and Herscovitch [27], commitment can be viewed as an experienced force, a state of mind or a psychological state that forces an individual to follow a relevant course of action to achieve one or more goal. Likewise, they identified three bases of commitment related to (i) desire, (ii) obligation and (iii) opportunity costs [27]. However, research on family businesses has treated commitment as a one-dimensional variable. To improve on these perceptions, and based on organizational commitment, [6] developed a multidimensional proposal for commitment in family businesses. The authors of [6] suggest that the successors’ decisions to pursue a career in the family business could be influenced by four different mid-sets that become the main reason to continue in the family business: affective, normative and continuance commitment (calculative and imperative).

Affective commitment is based on a strong belief in and acceptance of organizational goals, coupled with a desire to contribute to those goals and confidence in one’s ability to carry them out. In essence, the successor “wants to” pursue that career. Normative commitment “is based on an individual’s feeling obligation…” [6] (p. 17), in this case, to pursue a career in a family business. By pursuing a career in the family business, the successor feels loyalty as an intrinsic value within their family environment and tries to foster and maintain good relationships with the older generation. In short, successors with high levels of normative commitment feel that they have an “obligation” to pursue such a career option [6].

The two dimensions within the continuance commitment (calculate and imperative) may be linked to costs or types of compromises based on restrictions resulting from the perceived lack of better opportunities outside the company. In the case of calculative commitment, “it is based on successors’ perceptions of substantial opportunity costs and threatened loss of investments or value if they do not pursue a career in the family business. Successors with high levels of calculative commitment feel that they ‘have to’ pursue such a career” [6] (p. 3). The imperative commitment is based on the perception that there is no other employment option that is available to the potential successor of the family business. In other words, staying in the family business is the best career option; there is a “need” to be a successor in the family business.

Meyer and Allen [52] suggest that people can experience more than one dimension of commitment at a time. For example, it is quite possible to feel the desire (affective) and the obligation (normative) to remain in an organization at the same time [53]. Based on this, they suggested considering that people have a commitment profile which reflects different levels of each of the four foci that generate the different types of commitment [53].

One of the few studies that incorporates the commitment variable is that of [54]. They used the GUESSS 2013/2014 database for 18 countries and found that the affective commitment of daughters of fathers and/or mothers who are company owners positively affects the intention to succeed. Zellweger and Sieger [50], using data from GUESSS 2011 for 26 countries including Brazil, Mexico, Argentina and Chile, show that there is a direct and significant relationship between affective commitment and the intention to succeed in students with parents who own businesses. That is, students with a greater affective commitment to the family business will have a greater intention of being successors in the company. Along the same line, [55], based on a study of 106 German family firms, point out that adolescents with entrepreneurial parents have a greater predisposition to be successors, to the extent that they achieve an identification with the family business.

The empirical analysis of the multidimensionality of the commitment variable is scant [28]. Therefore, it is pertinent to analyse in depth whether the two main dimensions of commitment (affective and normative) appear as explanatory variables of the intention to be a successor by children of entrepreneurial men and/or women. Based on the above, we propose the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

The affective commitment has a direct and positive relation with the intention to be a successor in university students with entrepreneur parents.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

The normative commitment has a direct and positive relation with the intention to be a successor in university students with entrepreneur parents.

2.3. Parental Role Model and Intention to Become a Successor

The role model concept stems from the theory of social learning [30], which proposes that one way in which learning can occur is indirectly, through the observation of behaviour in other people, called models, and not by own experience. Based on this theory, the person observes the model in various social behaviours and, if positive results of this behaviour are identified, the person will try to replicate it. Consequently, the role model occurs when a social behaviour is detected and approved by a person. Bandura’s theory of social learning [30,31], together with the theory of cognitive development [56], assumes that children imitate adults, in particular parents, who are seen as role models [57].

Based on Bandura’s [30,31] theory, we will analyse the effect of the parental role model in the intention to succeed. Children of entrepreneurial parents are exposed from childhood to the behaviour of their parents running their own businesses. In this early socialization process, the family transmits not only information but also beliefs, social values, habits, attitudes and resources [34]; thus, the behaviour that children observe and learn from their parents decisively affects their development [33,35]. Growing up in such an environment of family entrepreneurship provides the children with perceptions of the business performance that motivate them towards behaviours [58].

Moreno-Gómez [39] show that having a parental role model increases the entrepreneurial intention of students from a Colombian university. Along the same lines, [59], while analysing the impact of parental self-employment on children’s self-employment in Denmark, shows that the parental role model is an important source of transmission of self-employment. Having an entrepreneurial parent increases the probability of a child becoming an entrepreneur by a factor of 1.3 to 3.0. Lindquist et al. [31] reach a similar conclusion from the analysis of child adoption by entrepreneurial parents in Sweden. In general, their findings show that entrepreneurial parents increase the probability of their children becoming entrepreneurs by about 60%. Lerchundi et al. [60] also show that entrepreneurial parents influence their children’s entrepreneurial intention. Likewise, [26,32,61,62,63] provide evidence of the positive influence played by the parents as role models in entrepreneurial intention. Other studies, such as [34], find that the parental role model acts in line with gender. Entrepreneurial fathers strongly influence their sons and entrepreneurial mothers influence their daughters, and the influence is stronger at an early age, before the 16th birthday, than in later years.

It is worth noting that the effect of the parental role model is also related with the perception that children have regarding the performance of their parents’ businesses. Wang [1] shows that the perception of rewards in the parents’ entrepreneurships are positively correlated with entrepreneurial intention. However, there are also studies that show a direct and negative correlation of the parental role model in entrepreneurial intention, especially when children perceive negative experiences from their parents’ entrepreneurship such as high family costs (parents’ separation, little time with the children), a high degree of stress or bankruptcy, among others [64]. Mungai and Valamuri [65] have shown a direct and negative effect when bankruptcy in the family business occurs; they emphasize that the impact of parents is more significant when the child is in the young adult stage (18–21 years) than in adolescence (12–17 years) or in childhood (8–11 years). Negative results are also observed in [24], where a direct but negative relationship between the parental role model and the entrepreneurial intention is evidenced in a sample of high school students.

Along the same lines, [4,45,63,66,67,68,69,70,71] have empirically and conceptually discussed the influence of role models on students’ entrepreneurial intention, concluding that these indirectly affect entrepreneurial intention through one, two or all three constructs of Ajzen’s [23] model.

Studies on parental role models in the intention to succeed among students with entrepreneurial parents are scarce. One study that comes close is [12]; it analyses the relationship between exposure to the family business (often understood as parental role model) and the intention to succeed among the offspring. The results show that exposure to family business has a negative effect on the intention to succeed and that the relationship is partially mediated by the affective commitment, this being stronger for sons than for daughters. As the results are inconclusive about the effects of parental role models on the succession intention among university students with entrepreneur parents, and considering that there is more empirical evidence that shows the direct and positive relationship of the parental role in the entrepreneurial intention, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The parental role model has a positive and significant relationship with the intention to be a successor of Latin American university students with entrepreneur parents.

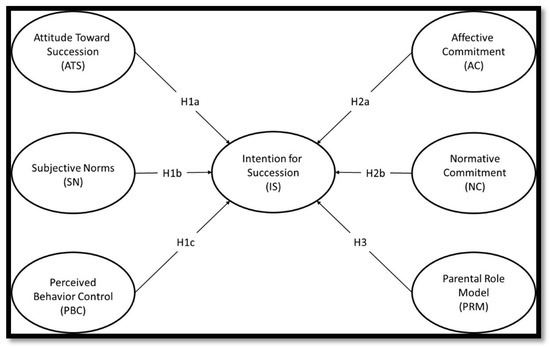

Taking into consideration that Ajzen’s [23] model can be extended with other variables if their relevance is justified and tested, and following [24], our theoretical model incorporates three more constructs to Ajzen’s original model. They are commitment, separated into the affective commitment and normative commitment and the parental role model, as explained below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical Model.

3. Methodology

The structure of this study responds to the research question: what are the determinants of the intention to be a successor among Latin American university students with entrepreneur parents? The theoretical basis is the model of planned behaviour of [23], together with the multidimensional proposal for the commitment to family businesses developed by [6] and the theory of social learning [30,31]. For this purpose, data from GUESSS 2018 were used. GUESSS is one of the largest entrepreneurship research projects in the world. The main research focus is students’ entrepreneurial intentions and activities, including the topic of family firm succession. It was established in 2003 at the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland). Every two–three years, a global data collection effort takes place. For every data collection, the GUESSS core team develops a high-quality online survey instrument. Survey invitations are then sent to the GUESSS country teams (one per country), who forward it to their own students and to their respective university partners (who then forward it to their students). The participation of the students is voluntary. Data are collected, stored and prepared by the GUESSS core, then they are distributed to each country teams. The GUESSS 2018 dataset was collected online between the months of October 2018 and January 2019; it contains more than 208,000 student respondents from 3191 universities in 54 countries around the world [72], from which 67,938 are Latin American students.

3.1. Characterization of the Sample

Our sample is composed of 16,185 Latin American university students with a father (6928), mother (3150) or both (6107) who are business owners. Men are 46.2% of the sample, and 53.7% are women. Regarding the age variable, 77% of the students are under 25 years old, 15% are between 25 and 30 and 8% are over 30 years old. The educational level of 87.6% of the sample is undergraduate, 11.1% has a master’s degree and 1.3% is studying a doctoral program. The surveyed students reside in Colombia (25.3%), Brazil (24.0%), Chile (12.2%), Mexico (10.4%), Costa Rica (9.9%), Ecuador (7.6%), Panama (5.0%), Argentina (3.3%), Uruguay (1.1%), El Salvador (1.0%) and Peru (0.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Student distribution by country.

When analysing the distribution of the population under study in terms of university career choice, it is observed that the two most relevant careers are business administration (29.4%) and engineering, including architecture (24.8%), with a total of 8763 students, equivalent to 54.2% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Career path distribution.

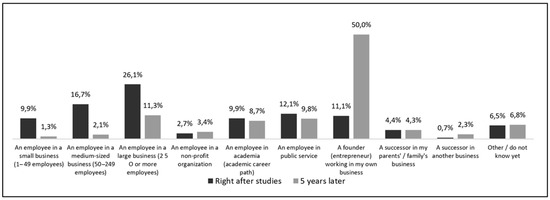

By way of a complement, the intention of the students to be a successor was examined in two periods of time: (i) at the end of the university career path and (ii) five years later. The questions were, which career path do you intend to pursue right after completion of your studies and which career path do you intend to pursue five years later? As can be seen in Figure 2, it is noteworthy that, at the end of the career, 26.1% wanted to be an employee of a large company, 11.1% wanted to start a business and only 4.4% wanted to be a successor. Five years later, 50% of the students declared that they wanted to start a business and 4.3% wanted to be a successor. The intention to be the successor of the family business remains stable in this period, while there is a significant increase in the entrepreneurial intention and the desire to work in a large company is reduced to 11.3%.

Figure 2.

Students’ career plans right after studies and five years later.

Continuing with the sample description, it is important to mention that, from the total of students with entrepreneurial parents, about 17.1% comprise the only child or are firstborn, and 82.9% have one or more older siblings (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of older siblings.

On the number of fulltime employees in the family business, the results show a median of three and a mode of one person. To make a classification by size, it is seen that 75% have fewer than 10 employees, of which 1.578, representing 9.75% of the sample, are self-employed (Table 4). That is, most businesses are microenterprises, and only about 1.43% have more than 200 employees.

Table 4.

Parents’ firms’ sizes *.

Regarding the economic sector where these businesses operate, around 23.8% of students noted the commerce sector (wholesale/retail), 6.7% chose the building sector and around 5.7% the manufacture sector. The option “other” was chosen by 28.9% of the students.

With respect to the parents’ firms’ performances during the last three years, in a scale from 1 = much worse to 7 = much better, 53.3% and 51.8% of the students considered that there was an increase in sales and profits in that period, respectively. Less than half of the number of students considered that there was an increase in market share (49.8%), in innovation (42.4%) and in business creation (36.6%) (Table 5). It seems as if, for over half of the number of students, their parents’ businesses do not have a good performance in the areas of innovation, market share and employment creation.

Table 5.

Student perception about performance of their parents´ firms.

To perform the validation of the proposed hypotheses, the partial least squares (PLS) method was used, which allows analysing multiple relationships between several variables of the construct type. The calculations were made using the statistical software package R (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) with add-in “plspm”. Reliability was analysed using Cronbach’s alpha. Values of 0.7, 0.8 and 0.9 are considered acceptable, good and excellent, respectively [73]. For convergent validity, the standardized factor loadings and communalities contained in the model were measured. Values greater than 0.7 were accepted. Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) was calculated for every latent construct (acceptable threshold is ≥0.5) [73].

Regarding the structural model, we examine the presence of collinearity among the predictor constructs, estimating the variance inflation factor (VIF) (obtained by bootstrapping) for each independent variable, which should be <5 [73]. High correlations may cause many problems in the interpretation of the results and in the model fit indices. To evaluate the structural model, we used two criteria: the coefficient determination (R2) and the analysis of the path coefficient.

It should be mentioned that the model is supported by the theoretical principles set out by [74], which establishes the use of this methodology as valid and with acceptable degrees of reliability in the data resulting from the study.

3.2. Description and Measurement of the Variables

The variables under consideration in this study were identified by analysing the statements evaluated by the GUESSS 2018 survey from 16,185 Latin American students. The latent variables were identified from a selection of statements according to the research objective within the GUESSS questionnaire. Intention for succession (IS), attitude toward succession (ATS) and subjective norms (SN) were measured, adapted from Liñan and Chen [49], using a Likert scale (1: strongly disagree to 7: strongly agree). An example statement of an IS variable is: “My professional goal is to become a successor in my parents’ business.” An example statement of an ATS variable is: “If I had the opportunity and resources, I would become a successor in my parents’ firm.” The statements for PBC used a Likert scale (1: very low competence to 7: very high competence). An example of this variable is: “Resolve disputes and/or manage conflicts with family members involved in the business.” Affective commitment and normative commitment are based on Dawson et al. [29], using a Likert scale (1: strongly disagree to 7: strongly agree). An example for affective commitment is: “My parents’ business has great personal meaning for me.” For normative commitment, an example is: “I feel an obligation to my family to pursue a career with my parents’ business.” Parental role model was based on Turner et al. [75], using a Likert scale (1: strongly disagree to 7: strongly agree). An example statement is: “My parents told me about the kind of work they do at their business.” For more details of the statements, see Appendix A. Table 6 shows the seven latent variables.

Table 6.

Detail of dependent and independent variables.

Additionally, we incorporated two control variables. The first one is Gender (G) (0 = male student; 1 = female student), following [2,3]. The second one, Siblings (S) (0 = first born; 1= one or more older siblings), was inspired by [37,38].

Observing the KMO (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin) indicator, it indicates that all the variables of the construct are appropriate to perform the exploratory factor analysis, since their values are greater than 0.9 [76]. For more details, see the KMO of each item in Appendix A. The factor analysis allows us to verify the conformation of each of the seven constructs analysed. On the other hand, the rotated component matrix shows the distribution of the contributions of the items to the latent variables (See Appendix B).

4. Results

The results are acceptable. Table 7 shows that the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of all the construct (latent variable) indicators are above 0.7 (minimum acceptable value for alpha), the smallest value being the normative commitment variable (0.893), while intention for succession (0.973) is the largest. The loadings have a correct adjustment over the cut-off 0.7. The metric of AVE is above the minimum acceptable coefficient of 0.5.

Table 7.

Reliability and Validity Evaluation.

There is no collinearity between variables of the model. For all constructs, the VIF is below the cut-off level (<5), with an average of 2.14 in the model. The results are in Table 8. Once the quality of the data analysed in the study and the structural part of the model had been evaluated, 78.2% of the variance was obtained with respect to the variable of intention, IS, which implies that the criteria for statistical adjustments are met with a goodness of fit measure (GOF) of 0.8054, greater than 0.7 [73].

Table 8.

Collinearity Test: Variance Inflation Factor (VIF).

Table 9 shows the correlations, where the variables with the highest level of correlation with the variable of intention, IS, are ATS (0.871), NC (0.737) and AC (0.732), while the lowest contribution is given by PRM (0.351) and PBC (0.366).

Table 9.

Item—Variables Correlations.

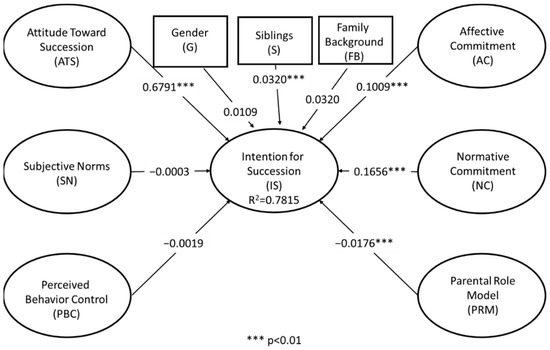

After performing an individual significance test of each variable in the model, the results indicate a direct relationship between ATS, AC and NC with the variable of intention, IS (Figure 3). All of them have 99% significance, ATS being the variable that has the greatest effect on IS, consistent with previous studies. The variables SN and PBC, which are determinant in Ajzen’s [23] model, are not significant in the proposed model, since their coefficients and standardized regression values linked to the construct have a p-value greater than 0.1. Therefore, hypothesis H1 is partially supported. The commitment variables, AC and NC, have a direct and significant relationship with the intention of being a successor; thus, hypotheses H2a and H2b are supported. The PRM variable, despite having a significant effect at the 99% level, exerts a negative influence on the intention to be a successor; therefore, hypothesis H3 is not supported. Out of the two control variables, only sibling is significant, while gender is not significant.

Figure 3.

Explanatory model of the intention to be a successor in the family business.

5. Discussion

This study seeks to identify the determinants of the intention to be a successor in Latin American university students with an entrepreneurial father, mother or both. The results show that the ATS is one of the most significant determinants of Ajzen’s model, which means that the stronger the ATS, the greater the intention to be a successor in the company of one’s parents. This result is consistent with the majority of studies [14,16,48] on entrepreneurial intention and intention to succeed, while the SN and the PBC were not significant for this study. Therefore, the hypothesis H1a is supported, and the hypotheses H1b and H1c are not supported. The reasons why SN are not significant could be related to several aspects: (a) SN is one of the constructs with the most controversial results. In most studies on entrepreneurial intention, SN is not significant [4,47,48,71], whereas in others, its effect is indirect, through PBC and ATS [49]; (b) in a few studies identified on university students with the intention to be a successor, this construct was not considered [14] and, in those in which it was considered, such as [16], the results are mixed. That is, the SN is only significant for university students with family business backgrounds from European countries with economies in transition, and it is not significant for students from European countries with market economies. Based on this, it seems that the SN are linked to economic and cultural aspects. It is important to highlight that the Latin American students considered for this study belong to market economies countries, and, therefore, our result is consistent with those obtained by [16], regarding the SN; (c) there is empirical evidence that the new generations have less interest and intention to work in their parents’ company [14,50,77,78]. In this study, the descriptive analysis clearly shows that the intention of this group of students at the end of their career is to work in a large company (26.1%), while only 4.4% intend to become successors. The situation changes when they are asked about their intention five years later. Fifty percent of this group declare that they want to have their own company, while the intention to be a successor falls slightly from 4.4% to 4.3%. It seems that this group of students prefers the independence of creating their own company over to be a successor in the family business. At the same time, it is increasingly apparent that social pressure from family or friends has less and less influence on the intention of university students to be a successor in the family business.

Contrary to expectations for the PBC construct, our result is not significant, therefore the self-efficacy perceived by Latin American students is not a determinant of the intention to be a successor. This result differs from that obtained by [50], in a sample of 93,000 students from almost 500 universities in 26 countries around the world, including Brazil, Mexico, Argentina and Chile. They find that PBC negatively affects the intention to be a successor, that is, the higher the PBC, the lower the intention to succeed in the family business. This result is probably also linked to the desire to start their own business and not to follow the family tradition.

Regarding commitment, the results confirm hypotheses H2a and H2b. That is, the emotional or affective commitment and the normative commitment of Latin American students is directly and positively related to the intention of being a successor in their parents’ companies. The first result is consistent with [50]. Likewise, it is consistent with [54], who analyse the intention of daughters to be successors in their parents’ businesses, in students from 18 countries including Brazil and Mexico. Along the same lines, [12] show that affective commitment leads to succession intentions but partially mediates the family business exposure–succession intentions relationship for students with family business based on 2013/2014 GUESSS data. These results indicate that Latin American students with entrepreneurial parents believe and accept the goals of their parents’ companies. They want to contribute to the achievement of those goals and, therefore, they also want to pursue that career. Along the same lines, our results also show that not only affective commitment is directly related to the intention to be a successor but also normative commitment (H2b), that is, the student´s feeling of obligation or the feeling that they “ought to” continue with the family business. Therefore, the two commitments, affective and normative, which are considered the most important in the succession process, are directly related to the intention to be a successor.

Finally, regarding the influence of parental role models on the intention to be a successor, the results show the existence of a direct but negative relationship. That is, for Latin American students, having entrepreneur parents negatively influences the intention to be a successor; hypothesis H3 is not supported. This unexpected result is consistent with that obtained by [24], who analysed the entrepreneurial intention in high school students in Spain, and [64], who found that prior entrepreneurial exposure, understood also as having self-employed parents, is negatively correlated with the intention to become an entrepreneur, or successor, as in the case of [12]. Their explanations are related to their parents’—their role models’—negative entrepreneurial experiences. This means that entrepreneurship has its costs, and this often requires spending more time in the company than with the family, or it may also imply higher costs, such as the parents’ separation. These situations mark the children and negatively influence their intention to be a successor. In this same line, [65] showed that the bankruptcy of the parents’ companies negatively affects the entrepreneurial intention. Extrapolating these results to the intention of being a successor in the family business, it could be suggested that parents with negative experiences in their companies or who have had extremely high family costs (such as marital separation and not being present at relevant family events, among others) are not role models for their children since they negatively affect the intention to succeed.

Another possible explanation, in this study, could be related to the students’ perceptions of the size of their parents’ businesses, the economic sector where they operate and the company’s performance. In the sample description, it was noted that 9.75% of the students have self-employed parents, and 65.34% of the students’ parents have businesses with fewer than 10 fulltime employees (Table 4). The majority of them operate in the commerce sector (wholesale/retail) (23.8%) and other services (10.3%). On the other hand, over 50% of Latin American students do not have a favourable perception about the performance of their parents’ firms, regarding the creation of jobs, innovation and market growth. It is worth noting that Latin America has a heterogenous productive structure and specializes in products of low added value and low innovation [79,80]. This impacts, in a decisive manner, the performance of small and microenterprises through low competitiveness and low share of exports [22]. Aspects such as a firm’s size, economic sector and perception of their performance could discourage students to become successors. Zellweger and Sieger [50] show that there is a positive correlation between company size and performance with IS. On the other hand, in developing countries such as in Latin America, being a university student carries a larger income premium compared with university students from developed countries [81]. This could be one of the reasons why the majority of Latin American students prefer to be hired at the end of their studies and become entrepreneurs only five years later. At any rate, these are issues that need to be explored in depth in future research [79,80].

In relation to our control variables, siblings are significant. This result means that having one or more siblings affects the intention to be a successor and is in line with the studies of Jayantilal et al. [38,82], who have found that, in a family where the potential successors are several siblings, there can be rivalry in the succession process, and the first one who shows interest or moves around the succession is the one who has more advantages in the succession process. Likewise, it is consistent with the study of Calabro et al. [37], who found, among others, that naming the second sibling as the successor of the family business has a positive and significant effect on the profitability of the firm after succession, particularly when the firm is in the second generation or later. The other control variable, gender, is not significant. In contrast to the results of [3] in Austria, and in line with [2] in Romania, gender does not affect the intention to be a successor.

Our study shows that the intention to be a successor in Latin American university students is more linked to attitude and to the affective and normative commitments they have with their parents’ companies and to the parents’ experiences as managers of the company. These experiences, when they are positive, can positively affect the intention to be a successor [1] and, conversely, if they are negative [24,64,65], they negatively affect the intention to be an entrepreneur and, consequently, could affect the intention to be a successor. According to [13], this result in some way would also be evidence of the existence of a crisis in the succession of family businesses. There is empirical evidence that shows the succession intentions of children of entrepreneurial parents have declined over time [14,50,77,78].

6. Conclusions

This study aims to determine the factors that explain the intention to be a successor in family businesses of Latin American university students with entrepreneur parents. To this end, the TPB was used as a basis to analyse the intention to be a successor and three constructs were added, two related to the organizational commitment of family businesses [6], namely affective commitment and normative commitment, and another, parental role model, related to Bandura’s theory of social learning [30,31]. The PLS method was used on a sample of 16,185 Latin American university students from the GUESSS 2018 database.

The results show that four out of six constructs proposed explain the intention to be a successor among university students with entrepreneurial parents. Similar to previous studies in developed countries, the attitude towards a certain behaviour is the main variable that explains the interest of young Latin American students to succeed in their parents’ companies. The other explanatory variables are affective and normative commitment [6] and the parental role model. This latter had a negative sign.

These results made it possible to verify that the role of parents is also relevant to stimulate the interest of young people to continue in the company of their parents through the commitment they can generate rather than through the role model they represent. In addition to the contributions previously mentioned, this study attempts to elucidate the factors that influence the intention of the students to be a successor at the Latin American level. The few studies that exist were carried out in developed countries. Given the high level of business informality in Latin America [48], and the continuity risks of family businesses [83], it is imperative to encourage the entrepreneurial capacity of family businesses to enhance the stability, growth and development of Latin American economies.

Our study contributes to the literature on university entrepreneurship and family business by showing empirical evidence of the determinants of intention to succeed among Latin American students with entrepreneurial parents. This is in a context in which a significant portion of the students are the first generation in the family to attend a university.

6.1. Implications

From a theoretical perspective, our study has shown that one of the key determinants of the intention to be a successor is attitude. The other two constructs of the Ajzen model [23] have not proven to be significant in this group of Latin American university students. This result contributes to a better understanding of Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour when it comes to analysing the intention to succeed among Latin American students with entrepreneurial parents. The study also extends the Ajzen model by incorporating three additional constructs: affective commitment, normative commitment and the parental role model, the first two with expected results and the third with a result in contradiction with expectations. About the latter, our study contributes to the academic discussion on the influence of parental models in the intention to succeed. It becomes apparent that the parental role model has a negative effect, which, in the case of Latin America students, could be linked to the offspring’s perception of the performance, size and sector of operation of the parents’ business. These results have important theoretical and practical implications for the owners of family businesses and the entrepreneurship education, as follows.

The theoretical implication is that Ajzen’s classic model contributes only partially towards explaining the succession intentions among Latin American students with entrepreneur parents. Future studies could improve the explanatory power of Ajzen’s model by introducing moderating or mediating factors to the model. For example, using “normative commitment” as a mediator between “subjective norms” and succession intention in order to verify whether subjective norms have an indirect effect in the intention to be a successor.

As a practical implication, the owners of family businesses must be more careful with the affective element to instil the intention of succession in their children. According to [59,65], the emotional aspects towards the family business must be developed from childhood, as these aspects can have a greater impact on motivation and, therefore, influence the intention of the successor to continue in the company. If this feeling of attachment to the company is correctly activated, it is likely to be offset by the negative effect found in the parental role model. Likewise, communication with their children is key; entrepreneur parents should communicate with their children on their experience as entrepreneurs and the advantages and disadvantages of being an entrepreneur, along with the satisfactions and dissatisfactions involved so that their children take an interest in continuing with the family business.

It is relevant to promote the variables that have been found as key to the intention of being a successor for young people to continue with their parents’ businesses. As long as they do not continue, there is a possibility that the company will stop working instead of contributing to its consolidation and growth. Young minds equipped with new knowledge acquired in the university and in their professional training can make the parents’ businesses grow and develop. Undoubtedly, the succession of companies by young professionals can be a crucial factor in strengthening and modernizing the organization, and taking it to a new level of production and profitability. In this sense, it is required to create instances to motivate or sensitize the young professionals to apply their university formation in the family business, thus enhancing its growth, competitiveness and development. In Latin America, many of university students are the first generation in the family with higher education. Therefore, they could strengthen and professionalize the family business.

One of those instances is through entrepreneurial education. Latin American universities should incorporate, in their programs, besides the entrepreneurship classes, courses on family business. As far as we know, these courses are taught at the graduate level but barely exist at the undergraduate level. A course on family business for undergraduates could contribute to raising awareness among them, in particular those with entrepreneurial parents, about the importance of these businesses for the local, regional and national development. Their university education could help their parents’ businesses to become more competitive, to generate more jobs and to transition from microenterprise to a medium or large company.

Along the same lines, the introduction of family business cases involving success and failure is advisable since it could contribute to sensitizing the audience and make them ponder regarding the possibility to take charge of their parents’ business. Inviting family business owners, men and women, to share their business experience, their hits and misses, could provoke in students another vision of their family businesses and foster the intention to succeed. These experiences could influence the desire of students, male and female, to take charge of their parents´ businesses.

6.2. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

In relation to the data, we can mention that they may have some statistical bias due to the composition of the sample used in the study. Considering the population of Latin American countries, our data have Colombia (25.3%) overrepresented and Peru (0.3%) and Argentina (3.3%) underrepresented.

A second aspect is that the results can be affected by a self-selection bias of the students themselves. Since the GUESSS survey is voluntary, students who respond to this survey may have a more entrepreneurial personality; therefore, their succession intentions are likely to be higher than those who do not respond to the survey. However, there is a growing number of studies based on the GUESSS survey which are considered adequate [39,48]. In the same vein, the study’s sample is restricted to university students with more formal education than their peers at the same age outside of higher education. Therefore, the results of this study should be dealt with cautiously before generalizing.

Third, the study covers information only at a certain moment in time. A longitudinal analysis could be more precise and useful, particularly if done with final-year students, in order to analyse career patterns five years after finishing their university studies and of what type of business they intend to become successors of. This study might validate whether the students who expressed their interest in being entrepreneurs actually do so or become employees. In the same vein, future research would complement this study with qualitative research that allows exploring the reasons why students who are the children of entrepreneurs do not intend to be successors but rather to be entrepreneurs five years after graduation. Topics such as the occupational choices of students from an economic perspective [84] could be addressed in future research.

A fourth limitation to remark is that the results of this article specifically refer to the circumstances of Latin American countries and cannot be generalized to other contexts due to the differences in terms of characteristics of entrepreneurial activity, economic development, institutions and cultural values. In any case, the results can be useful to understand succession intentions in countries where necessity and low-value-added ventures predominate [21,22,85,86].

A last limitation is that our model incorporates the gender only as a control variable. Future studies might analyse the succession intention of male and female students whose father, mother or both are entrepreneurs, to elucidate if, in the Latin America case, the intention to succeed in university students is directly linked to having an entrepreneurial father, mother or both, as suggested by several studies [12,32,34,87]. These studies would be particularly interesting in societies such as Latin America, where businesses led by men are more predominant [88]; knowing these results would have practical implications to improve the entrepreneurial education and a better understanding of the succession process in a family business.

Continuing with gender, in our study, 19.5% of students have an entrepreneur mother and very little is known about the succession process of companies led by women [89], particularly in Latin America. Following the work by [90,91], future research could include case studies with a qualitative focus on established women entrepreneurs who are beginning a succession process, to find out whether they have a succession strategy or are doing something else to address this subject. On the other hand, in some Latin American countries, entrepreneurship is still a way to escape poverty and achieve financial independence, particularly for women; therefore, currently, there are more entrepreneurial women. Along these lines, and following [92], it is also worth exploring whether entrepreneur mothers empower their daughters to take over the company, above all to give continuity to the company and, at the same time, to provide them with financial independence in emerging countries where there is often a lack of employment. Other studies could address the preferences of mothers regarding their children, whether they encourage their daughters to have more succession intention, and what strategies they use to achieve this.

In addition to gender, our model has considered the number of older siblings as a control variable with significant results. Following the works of [12,37,38], future studies could delve into these variables, analysing the effect of the primogeniture in the intention of succession or the differences between the first-born children versus those with one or more older sibling in the intention to be a successor in parents´ businesses and if these differences are maintained when the first-born is a male or female student. These results could have important practical implications to improve the entrepreneurial education and family business as well.

On the other hand, our article includes only two commitment variables (affective and normative); future studies could include all the commitment variables developed by Sharma and Irwing [6] with a focus on gender, as proposed by [93], in order to find out whether these variables affect succession intentions in the same way when dealing with male and female students.

Future research that emerges from these limitations should analyse the intention to succeed considering aspects related to the parents´ firms such as performance, size, economic sector, where they operate and age. These aspects are more important in countries such as those in Latin America, where the heterogeneity in business performance is high [22,79,80]. On one hand, microenterprises respond mainly to self-employment needs, are often in a situation of informality [21] with low levels of human capital, have difficulty in accessing external financial resources, experience little internationalization and carry out activities with low technical requirements. At the other extreme, there are also small and medium-sized companies with high growth potential, both in terms of turnover and job creation, and whose performances respond to taking advantage of market opportunities through efficient and innovative business management [22]. Therefore, the size of the company, the performance and the age of the same can affect the perception of students with entrepreneurial parents in their intention to succeed.

Another future line of research is to analyse the effects that different types of universities and the type of education students receive have on the intention to be a successor in their parents’ companies. It would be expected that students who are the children of entrepreneurs and who study in universities where the education is oriented towards entrepreneurship would have a higher intention to be successors than those who study in universities without an entrepreneurial orientation.

Additionally, the culture of each country can affect the intention to succeed in the parents´ businesses. Perhaps in countries considered more individualistic, the succession process is not affected by the commitment variables, while in countries considered more collectivist, such as in most Latin American countries, these variables indeed have an effect. Finally, other studies may stress the contribution of business education and/or the university environment as variables to promote the intention of being a successor, either as a mediating variable or by making the variables of the Ajzen´s model the mediators.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.R. and K.S.-B.; methodology, G.H.-M., R.R.E. and J.R.; software, G.H.-M. and R.R.E.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors.; writing—review and editing, G.R. and K.S.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Católica del Norte (protocol code 019/2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

GUESSS 2018 Questionnaire Statements for Definition of Latent Variables.

Table A1.

GUESSS 2018 Questionnaire Statements for Definition of Latent Variables.

| 1. Intention for Succession (IS)—Dependent variable 1 = Strongly disagree; 7 = Strongly agree. | KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) | |

| is1 | I am ready to do anything to take over my parents’ business. | 0.99 |

| is2 | My professional goal is to become a successor in my parents’ business. | 0.98 |

| is3 | I will make every effort to become a successor in my parents’ business. | 0.97 |

| is4 | I am determined to become a successor in my parents’ business in the future. | 0.97 |

| is5 | I have very seriously thought of taking over my parents’ business. | 0.98 |

| is6 | I have the strong intention to become a successor in my parents’ business one day. | 0.97 |

| 2. Attitude Toward Succession (ATS)—Independent variable 1 = Very negatively; 7 = Very positively | ||

| ats2 | A career as a successor is attractive for me. | 0.99 |

| ats3 | If I had the opportunity and resources, I would become a successor in my parents’ firm. | 0.98 |

| ats4 | Being a successor would entail great satisfactions for me. | 0.97 |

| ats5 | Among various options, I would rather become a successor in my parents’ firm. | 0.98 |

| 3. Subjective Norms (SN)—Independent variable 1 = Very negatively; 7 = Very positively | ||

| sn1 | If you would become a successor taking over your parents’ business, how would people in your environment react?—Your parents | 0.96 |

| sn2 | If you would become a successor taking over your parents’ business, how would people in your environment react?—Close family members | 0.93 |

| sn3 | If you would become a successor taking over your parents’ business, how would people in your environment react?—Other family members (e.g., uncles and aunts) | 0.93 |

| sn4 | If you would become a successor taking over your parents’ business, how would people in your environment react?—People outside the family (e.g., friends, colleagues) | 0.97 |

| 4. Perceived Control Behaviour (PBC)—Independent variable 1 = Very low competence; 7 = very high competence | ||

| pbc1 | Please indicate your level of competence in performing the following tasks …Resolve disputes and/or manage conflicts with family members involved in the business. | 0.95 |

| pbc3 | …Conduct negotiations with the incumbent leader of the family firm. | 0.95 |

| pbc4 | …Act diplomatically when different views emerge among family members. | 0.95 |

| pbc6 | …Resolve disputes and/or manage conflicts with non-family employees. | 0.95 |

| pbc7 | …Maintain and build healthy relationships with external stakeholders. | 0.91 |

| pbc8 | …Resolve disputes and/or manage conflicts with external stakeholders. | 0.90 |

| 5. Affective Commitment (AC)—Independent variable 1 = Strongly disagree; 7 = Strongly agree | ||

| ac2 | I feel a sense of belonging to my parents’ business. | 0.98 |

| ac3 | I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with my parents’ business. | 0.98 |

| ac4 | I feel emotionally attached to my parents’ business. | 0.96 |

| ac5 | My parents’ business has great personal meaning for me. | 0.96 |

| 6. Normative Commitment (NC)—Independent variable 1 = Strongly disagree; 7 = Strongly agree | ||

| nc1 | I feel an obligation to my family to pursue a career with my parents’ business. | 0.96 |

| nc2 | My parents’ business deserves my loyalty. | 0.98 |

| nc3 | I would feel guilty if I did not pursue a career with my parents’ business. | 0.96 |

| 7. Parental Role Model (PRM)—Independent variable 1 = Strongly disagree; 7 = Strongly agree | ||

| prm1 | My parents told me about the kind of work they do at their business. | 0.90 |

| prm2 | My parents told me about things that happen to them at their business. | 0.90 |

| prm3 | My parents have taken me to their business. | 0.96 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Rotated Component Matrix.

Table A2.

Rotated Component Matrix.

| IS | ATS | PBC | SN | AC | NC | PRM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| is1 | 0.82 | ||||||

| is2 | 0.95 | ||||||

| is3 | 0.96 | ||||||

| is4 | 0.97 | ||||||

| is5 | 0.91 | ||||||

| is6 | 0.95 | ||||||

| ats2 | 0.88 | ||||||

| ats3 | 0.91 | ||||||

| ats4 | 0.93 | ||||||

| ats5 | 0.94 | ||||||

| pbc1 | 0.69 | ||||||

| pbc3 | 0.71 | ||||||

| pbc4 | 0.71 | ||||||

| pbc6 | 0.91 | ||||||

| pbc7 | 0.92 | ||||||

| pbc8 | 0.94 | ||||||

| sn1 | 0.87 | ||||||

| sn2 | 0.93 | ||||||

| sn3 | 0.90 | ||||||

| sn4 | 0.83 | ||||||

| ac2 | 0.83 | ||||||

| ac3 | 0.85 | ||||||

| ac4 | 0.91 | ||||||

| ac5 | 0.86 | ||||||

| nc1 | 0.94 | ||||||

| nc2 | 0.78 | ||||||

| nc3 | 0.88 | ||||||

| prm1 | 0.94 | ||||||

| prm2 | 0.94 | ||||||

| prm3 | 0.83 |

References

- Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Chen, L. Unlocking the influence of family business exposure on entrepreneurial intentions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 951–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, M.A.; Herman, E. The impact of the family background on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: An empirical analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.; Fasbender, U.; Kraus, S.; Birkner, S.; Kailer, N. A chip off the old block? The role of dominance and parental entrepreneurship for entrepreneurial intention. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 15, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birley, S. Attitudes of owner-managers’ children towards family and business issues. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 26, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Irving, G. Four Bases of Family Business Successor Commitment: Antecedents and Consequences. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basco, R.; Calabro, A. Whom do I want to be the next CEO? Desirable successor attributes in family firms. J. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 87, 487–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticelli, J.M.; Bernardon, R.; Trez, G. Family as an institution: The influence of institutional forces in transgenerational family businesses. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 26, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubíček, A.; Machek, O. Gender-related factors in family business succession: A systematic literature review. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019, 13, 963–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, J.; Donckels, R. Towards a business family dynasty: A lifelong, continuing process. In Handbook of Research on Family Business; Poutziouris, P.Z., Smyrnios, K.X., Klein, S.B., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 388–402. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola, P.; Marchisio, G.; Astrachan, J.H. Using the strategic planning process as a next-generation training tool in family business. In Handbook of Research on Family Business; Poutziouris, P.Z., Smyrnios, K.X., Klein, S.B., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 402–422. [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Jimenez, D.; Edelman, L.F.; Minola, T.; Calabro, A.; Cassia, L. An Intergeneration Solidarity Perspective on Sucession Intentions in Family Firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 45, 740–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, P.; Sharma, P.; De Masis, A.; Wright, M.; Scholes, L. Perceived Parental Behavior and Next Generation Engagement in Family Firms: A Social Cognitive Perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T.; Sieger, P.; Halter, F. Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, H.; Hundt, C.; Sternberg, R. What makes tudent entrepreneurs? On the relevance (and irrelevance) of the university and the regional context for student start-ups. Small Bus Econ. 2016, 47, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubotina, P.; Gomezelj, D.; Vadnjal, J. Succeeding a family business in a transition economy: Following business goals or do it my own way? Serb. J. Manag. 2018, 13, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, P.; Botero, I.; Arzubiaga, U.; Memili, E.; Gómez-Mejía, L.; Durán, P. Family business in Latin America. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2020, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charry, L. Las Empresas Familiares de América Latina. 2020. Available online: https://www.aviancaenrevista.com/revista/empresas-familiares-america-latina/#:~:text=Las%20empresas%20familiares%20son%20el,empleos%20y%20son%20tremendamente%20influyentes (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- INSEAD The Institutionalization of Family Firms in Latin America. 2019. Available online: https://www.insead.edu/sites/default/files/assets/dept/centres/gpei/docs/The_Institutionalization_of_Family_Firms_Latin_America_Mar_2019.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- Fernández-Pérez, P.; Lluch, A. Evolution of Family Business: Continuity and Change in Latin America and Spain; Edward Elgar Publishing: Chelteham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- OCDE/CAF/CEPAL. Perspectivas Económicas de América Latina 2018; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dini, M.; Stumpo, G. (Coords.) MIPYMES en América Latina: Un FrágilD y nuevos Desafíos Para Las Políticas de Fomento. Documentos de Proyectos (LC/TS.2018/75/Rev.1); Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL): Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Ferreira, J.; Gómez, D.; Gouveia, R. Entrepreneurship Education: How psychological, demographic and behavioural factors predict the Entrepreneurial Intention. Educ. Train. 2012, 54, 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieger, P.; Fueglistaller, U.; Zellweger, T. Student Entrepreneurship 2016: Insights from 50 Countries; KMU-HSG/IMU: St. Gallen/Bern, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Criaco, G.; Sieger, P.; Wennberg, K.; Chirico, F.; Minnola, T. Parents’ performance in entrepreneurship as a “double-edged sword for the intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 841–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Herscovitch, L. Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2001, 11, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. Determinants of the Satisfaction of the Primary Stakeholders with the Succession Process in Family Firms. PhD Dissertation, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, A.; Irving, G.; Sharma, P.; Chirico, F.; Marcus, J. Behavioural outcomes of next-generation family members’ commitment to their firm. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cffs, NJ, USA; Stranford, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundation of Thought and Action: A Social-Cognitive view Theory; Prentice-Hall: EngleWood Cliffs, NJ, USA; Stranford, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist, M.J.; Sol, J.; Van Praag, M. Why do entrepreneurial Parente have entrepreneurial children? J. Labor Econ. 2015, 33, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlosta, S.; Patzelt, H.; Klein, S.B.; Dormann, C. Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: The moderating effect of personality. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 38, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladasel, T.; Lindquist, M.J.; Sol, J.; Van Praag, M. On the origins of entrepreneurship: Evidence from sibling correlations. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.F.; Brodzinski, J.D.; Wiebe, F. Examining the relationship between personality and entrepreneurial career preference. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1991, 3, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, N.; Shane, S.; Cherkas, L.; Hunkin, J.; Spector, D. Is the tendency to engage in Entrepreneurship Genetic? Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabro, A.; Minichilli, A.; Amore, M.D.; Brogi, M. The courage to choose! Primogeniture and leadership succession in family firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 2014–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayantilal, S.; Ferreira, S.; Bañegil, T.M. First mover advantage on family firm succession. Int. J. Appl. Manag. Sci. 2019, 11, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gómez, J.; Gómez-Araujo, E.; Castillo-De Andreis, R. Parental role models and entrepreneurial intentions in Colombia. Does gender play a moderating role? J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 12, 413–429. [Google Scholar]

- Stampoltzis, A.; Tstsou, E.; Papachristtopoulos, S. Attitudes and intentions of Greek teachers towards teaching pupils with dyslexia: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Dislexia 2018, 24, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Oveisi, S.; Burri, A.; Pakpour, A.H. Theory of Planned Behavior including self-stigma and perceived barriers explain help-seeking behavior for sexual problems in Iranian women souring from epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017, 68, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.C.; Wang, H.H.; Chien, T.W. Hospital nurses’ attitudes, negative perceptions, and negative acts regarding workplace bullying. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2017, 15, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regalado, O.; Guerrero, C.; Montalvo, R. Una aplicación de la teoría del comportamiento planificado al segmento masculino latinoamericano de productos de cuidado personal. Rev. Esc. De Adm. De Neg. 2017, 83, 41–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kolvereid, L. Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1996, 21, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvereid, L.; Isaksen, E. New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. J. Bus. Ventur. 2006, 21, 866–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachev, A.; Kolvereid, L. Self-employment intentions among Russian students. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1999, 11, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Keeley, R.H.; Klofsten, M.; Parker, G.; Hay, M. Entrepreneurial intent among students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterp. Innov. Manag. Stud. 2001, 2, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, T.; Álvarez, C. Influence of university-related factors on students’entrepreneurial intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2019, 11, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y. Development and Cross-Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T.; Sieger, P.; Englisch, P. Coming Home or Breaking Free? Career Choice Intentions of the Next Generation in Family Business. Report. 2012. Available online: http://www.guesssurvey.org/resources/pract/Coming_Home_or_Breaking_Free.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Gilding, M. Family business and family change: Individual autonomy, democratization, and the new family business institutions. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2000, 13, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research and Application; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gellatly, I.R.; Meyer, J.P.; Luchak, A.A. Combined effects of three commitment components on focal and discretionary behaviors: A test of Meyer and Herscovitch’s propositions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, D.; Edelman, L.; Calabro, A.; Minola, T.; Cassia, L. The impact of affective commitment on daughters’succession intentions in family firms: The role of family firm ownership structure and in-group collectivism. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proc. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, E.; Schmitt-Rodermund, E.; Arnaud, N. Career choice intentions of adolescents with family business background. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2011, 24, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. A cognitive developmental analysis of children’s sex role concepts and attitudes. In The Development of Sex Differences; Maccoby, E.E., Ed.; Stanford University Press: Stranford, CA, USA, 1966; pp. 82–173. [Google Scholar]

- Dryler, H. Parental Role Models, Gender and Educational Choice. Br. J. Sociol. 1998, 49, 375–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]