Responsible Management in the Hotel Industry: An Integrative Review and Future Research Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

How have responsible management practices been examined in the industry-specific literature, which areas of scholarship on this industry remain under-researched, and what are the criteria of responsibility examined in studies on management of hotels?

2. Materials and Methods

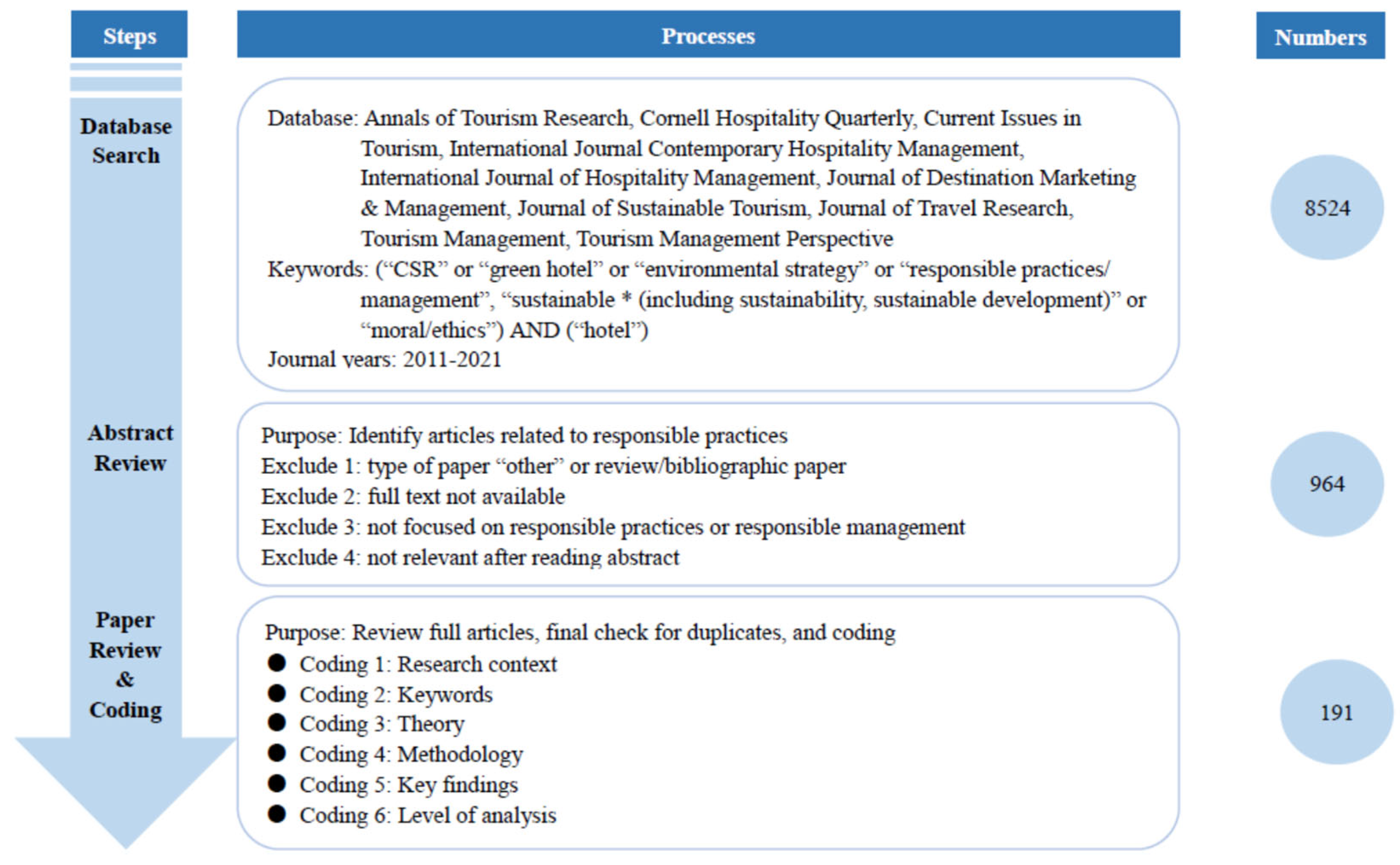

2.1. Process of the Literature Review

2.2. Journal Selection

- Annals of Tourism Research

- Cornell Hospitality Quarterly

- Current Issues in Tourism

- International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management

- International Journal of Hospitality Management

- Journal of Destination Marketing & Management

- Journal of Sustainable Tourism

- Journal of Travel Research

- Tourism Management

- Tourism Management Perspective

2.3. Reviewing Process

3. Results

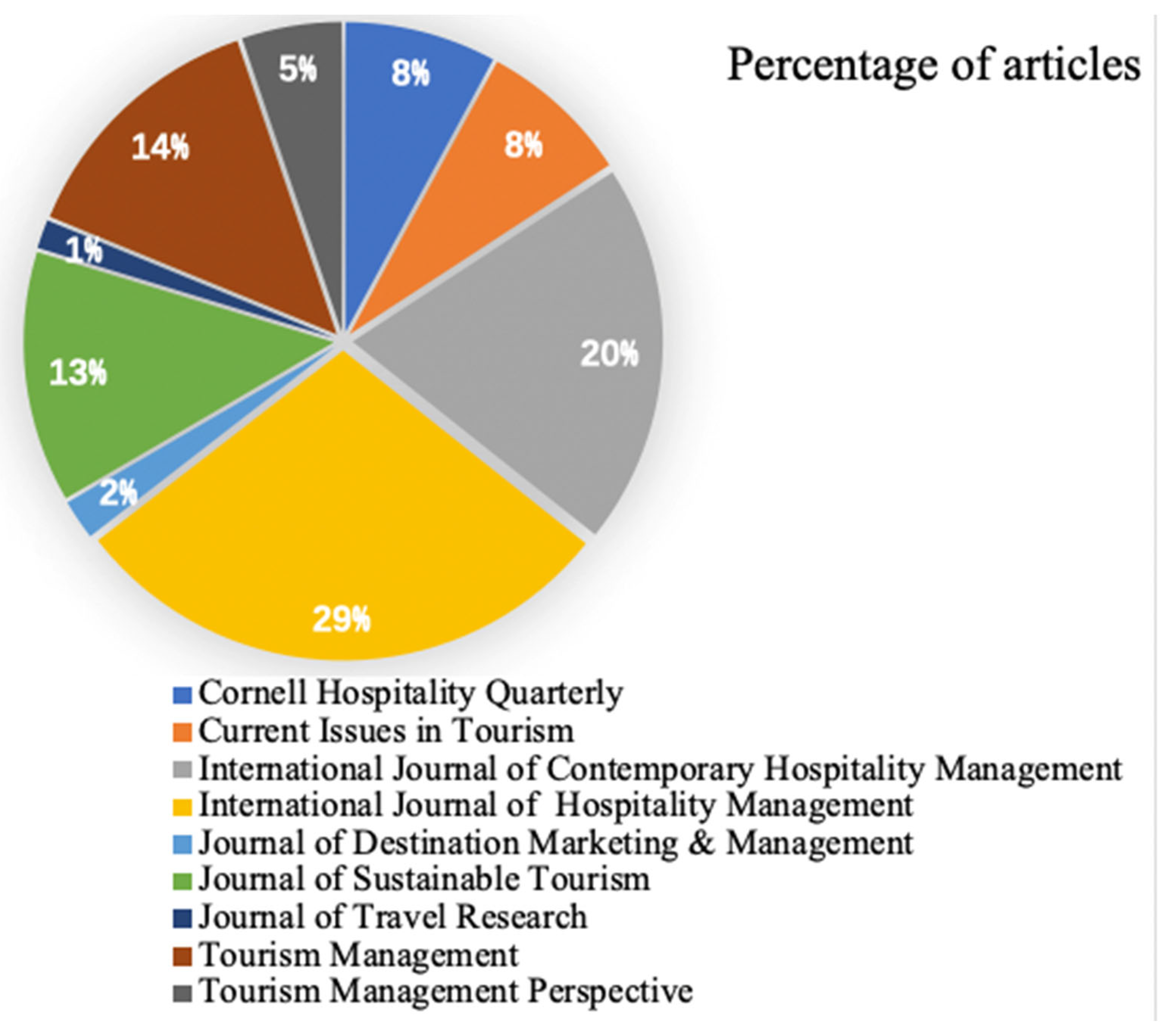

3.1. Annual Publications in the Top 10 Journals

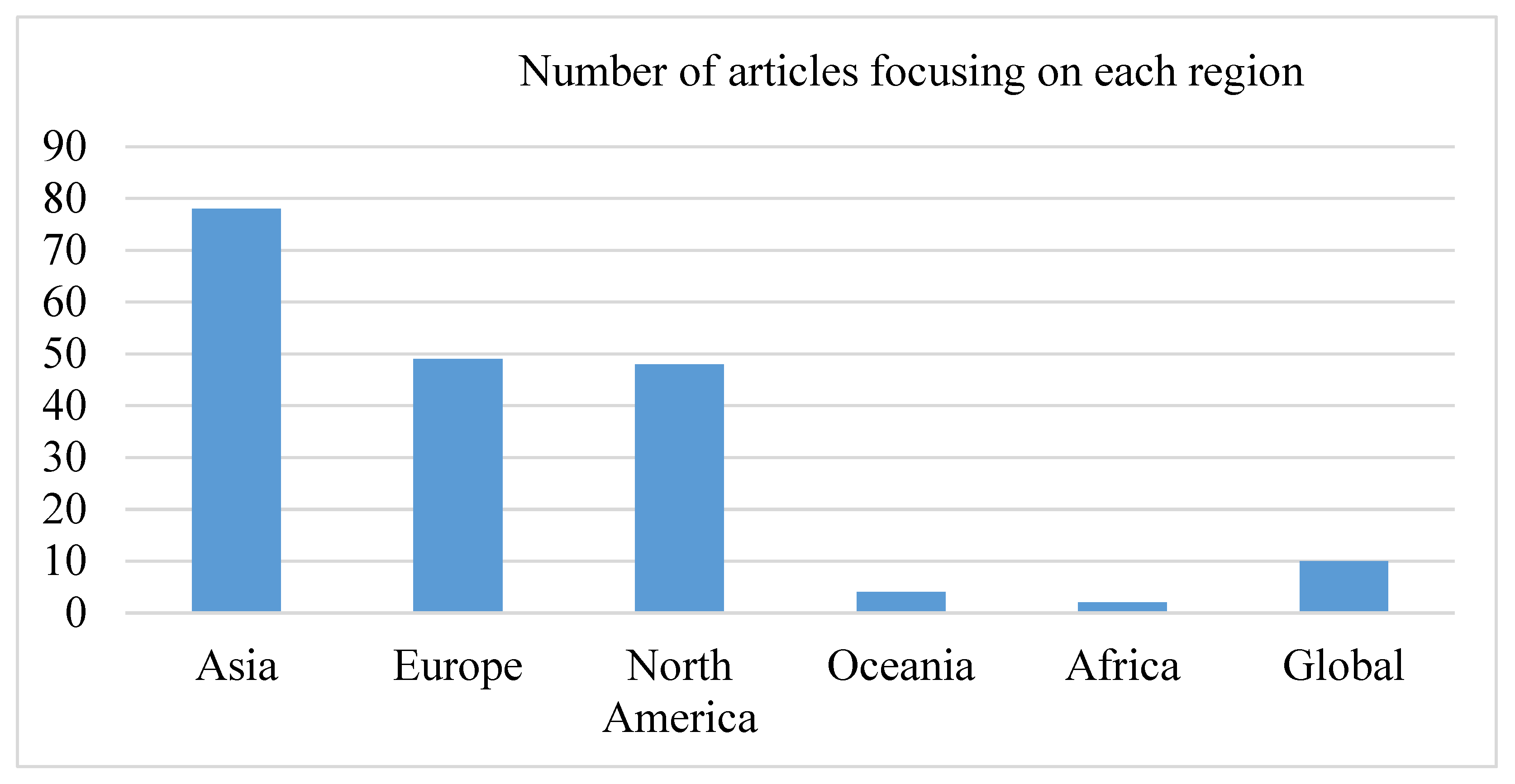

3.2. Research Region

3.3. Research Methods

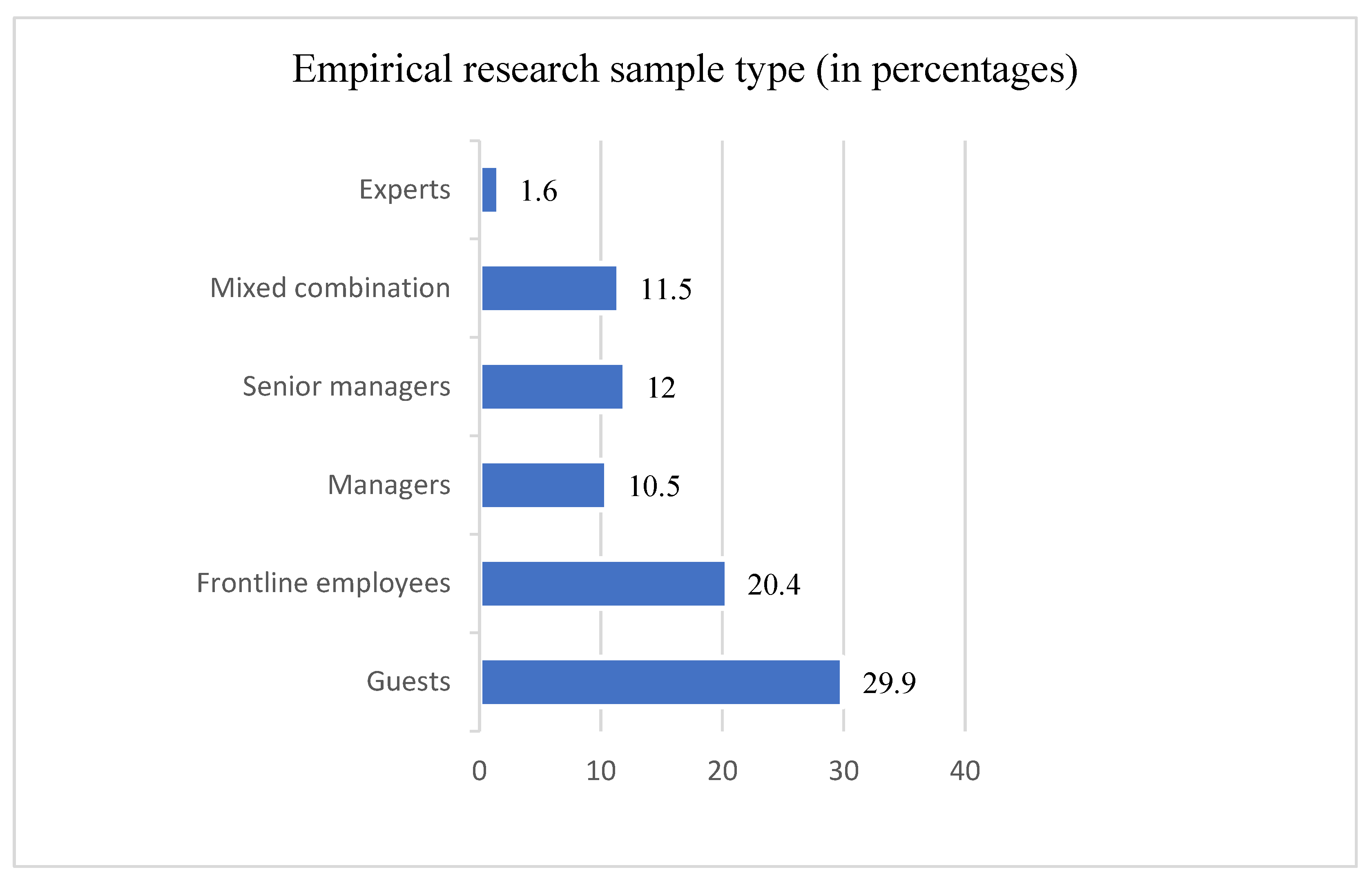

3.4. Categories of the Unit of Analysis

3.4.1. Firm-Level Research

3.4.2. Individual-Level Research

3.5. Responsible Practice and Guests

3.6. Responsible Practice and Employees

4. Discussion, Implications, and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giza, W.; Wilk, B. Revolution 4.0 and its implications for consumer behaviour. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2021, 9, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, M.; Jiang, Y.; Jha, S. Green hotel adoption: A personal choice or social pressure? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3287–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Leung, R. Smart hospitality—Interconnectivity and interoperability towards an ecosystem. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Soto, E.; Armas-Cruz, Y.; Morini-Marrero, S.; Ramos-Henríquez, J.M. Hotel guests’ perceptions of environmental friendly practices in social media. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, Y.; Awang, Z.; Jusoff, K.; Ibrahim, Y. The influence of green practices by non-green hotels on customer satisfaction and loyalty in hotel and tourism industry. Int. J. Green Econ. 2017, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoulidis, B.; Diaz, D.; Crotto, F.; Rancati, E. Exploring corporate social responsibility and financial performance through stakeholder theory in the tourism industries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Martín-Samper, R.C.; Köseoglu, M.A.; Okumus, F. Hotels’ corporate social responsibility practices, organizational culture, firm reputation, and performance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, P.V.; Sreejesh, S. Impact of responsible tourism on destination sustainability and quality of life of community in tourism destinations. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatter, A.; McGrath, M.; Pyke, J.; White, L.; Lockstone-Binney, L. Analysis of hotels’ environmentally sustainable policies and practices: Sustainability and corporate social responsibility in hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2394–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyeen, A.; Kamal, S.; Yousuf, M.A. A content analysis of CSR research in hotel industry, 2006–2017. In Responsibility and Governance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Sinkovics, N.; Reuber, A.R. Beyond disciplinary silos: A systematic analysis of the migrant entrepreneurship literature. J. World Bus. 2021, 56, 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, E.C. Rural entrepreneurial ecosystems: A systematic literature review for advancing conceptualisation. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2021, 9, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Crossan, M.M.; Apaydin, M. A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1154–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracevic, S.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. The impact of social norms on pro-environmental behavior: A systematic literature review of the role of culture and self-construal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5156. [Google Scholar]

- GoogleScholar. GS Metrics. 2021. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=top_venues&hl=en&vq=bus_tourismhospitality (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- Abaeian, V.; Khong, K.W.; Yeoh, K.K.; McCabe, S. Motivations of undertaking CSR initiatives by independent hotels: A holistic approach. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2468–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Maksoud, A.; Kamel, H.; Elbanna, S. Investigating relationships between stakeholders’ pressure, eco-control systems and hotel performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 59, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-García, C.; Marchante-Lara, M.; Benavides-Chicón, C.G. Social responsibility and total quality in the hospitality industry: Does gender matter? J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 722–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Vijande, M.L.; López-Sánchez, J.Á.; Pascual-Fernandez, P. Co-creation with clients of hotel services: The moderating role of top management support. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 301–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.; Chang, R.C. The driving and restraining forces for environmental strategy adoption in the hotel industry: A force field analysis approach. Tour. Manag. 2019, 73, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. (Ed.) Innovation of Higher Education in Hotel Management Based on International Perspective. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2019); Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, T.-Y.; Chuang, C.-M.; Huang, L. The contents, determinants, and strategic procedure for implementing suitable green activities in star hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-P.; Wu, C.-M.E.; Tsai, J.-H. Why hotels give to charity: Interdependent giving motives. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Wei, W.; Chi, C.G. Environment management in the hotel industry: Does institutional environment matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rech, Y.; Paget, E.; Dimanche, F. Uncertain tourism: Evolution of a French winter sports resort and network dynamics. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 12, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rosario, R.-S.M.; René, D.-P. Eco-innovation and organizational culture in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 65, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P. Influence of brand signature, brand awareness, brand attitude, brand reputation on hotel industry’s brand performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-C.; Lu, A.C.C.; Huang, T.-T. Drivers of consumers’ behavioral intention toward green hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1134–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untaru, E.-N.; Ispas, A.; Candrea, A.N.; Luca, M.; Epuran, G. Predictors of individuals’ intention to conserve water in a lodging context: The application of an extended theory of reasoned action. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 59, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Font, X.; Liu, J. Antecedents, mediation effects and outcomes of hotel eco-innovation practice. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gázquez-Abad, J.C.; Huertas-García, R.; Vázquez-Gómez, M.D.; Casas Romeo, A. Drivers of sustainability strategies in Spain’s wine tourism industry. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2015, 56, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grosbois, D. Corporate social responsibility reporting by the global hotel industry: Commitment, initiatives and performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kularatne, T.; Wilson, C.; Månsson, J.; Hoang, V.; Lee, B. Do environmentally sustainable practices make hotels more efficient? A study of major hotels in Sri Lanka. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimara, E.; Manganari, E.; Skuras, D. Don’t change my towels please: Factors influencing participation in towel reuse programs. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Eliciting customer green decisions related to water saving at hotels: Impact of customer characteristics. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1437–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Juvan, E.; Grün, B. Reducing the plate waste of families at hotel buffets–a quasi-experimental field study. Tour. Manag. 2020, 80, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, B.; Taheri, B.; Giritlioglu, I.; Gannon, M.J. Tackling food waste in all-inclusive resort hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarda-Mallorquí, A.; Garcia, X.; Ribas, A. Mass tourism and water efficiency in the hotel industry: A case study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 61, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, A.; Olcina, J.; Baños, C.; Garcia, X.; Sauri, D. Declining water consumption in the hotel industry of mass tourism resorts: Contrasting evidence for Benidorm, Spain. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 770–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez–Sanchez, C.; Sancho-Esper, F.; Casado-Diaz, A.B.; Sellers-Rubio, R. Understanding in-room water conservation behavior: The role of personal normative motives and hedonic motives in a mass tourism destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Knezevic Cvelbar, L.; Grün, B. Do pro-environmental appeals trigger pro-environmental behavior in hotel guests? J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Chen, A. Luxury hotels going green–the antecedents and consequences of consumer hesitation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1374–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razumova, M.; Ibáñez, J.L.; Palmer, J.R.-M. Drivers of environmental innovation in Majorcan hotels. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1529–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourvinou, A.; Filimonau, V. Planning for an environmental management programme in a luxury hotel and its perceived impact on staff: An exploratory case study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Montes, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Law, R.; Han, H. Incidence of workplace bullying among hospitality employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1116–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, A.; Gross, M.J.; Sardeshmukh, S.R. Identity-conscious vs identity-blind: Hotel managers’ use of formal and informal diversity management practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wen, J. Effects of COVID-19 on hotel marketing and management: A perspective article. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2563–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. 5 Charts Show Which Travel Sectors Were Worst Hit by the Coronavirus; CNBC: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, C.; Wang, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Responding to a major global crisis: The effects of hotel safety leadership on employee safety behavior during COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3365–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavero-Rubio, J.A.; Amorós-Martínez, A. Environmental certification and Spanish hotels’ performance in the 2008 financial crisis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 771–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lee, S. Revisiting the financial performance–corporate social performance link. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2586–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E.; Matute, J.; Melero, I. Environmental strategies and organizational competitiveness in the hotel industry: The role of learning and innovation as determinants of environmental success. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza-Sáez, P.C.; Claver-Cortés, E.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Úbeda-García, M. Corporate social responsibility and strategic knowledge management as mediators between sustainable intangible capital and hotel performance. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.; Caroli, M.G.; Cappa, F.; Del Chiappa, G. Are you good enough? CSR, quality management and corporate financial performance in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.; Jang, J.; Lee, J.J. Environmental management strategy and organizational citizenship behaviors in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1577–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Vo-Thanh, T.; Huynh, T.L.D.; Santos, C. Greening hotels: Does motivating hotel employees promote in-role green performance? The role of culture. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Thanh, T.V.; Tučková, Z.; Thuy, V.T.N. The role of green human resource management in driving hotel’s environmental performance: Interaction and mediation analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Florencio, B.; Garcia del Junco, J.; Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Rosa-Díaz, I.M. Trust as mediator of corporate social responsibility, image and loyalty in the hotel sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1273–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, K.F.; Pérez, A.; Sahibzada, U.F. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and customer loyalty in the hotel industry: A cross-country study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P. Customer loyalty: Exploring its antecedents from a green marketing perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 896–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.J.; Lee, J.-S.; Sheu, C. Are lodging customers ready to go green? An examination of attitudes, demographics, and eco-friendly intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, L.; Zhang, L.; Line, N.; McGinley, S. When less is more: Sustainability messaging, destination type, and processing fluency. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 58, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, S.K.; Elshaer, I.A. Justice and trust’s role in employees’ resilience and business’ continuity: Evidence from Egypt. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Nazarian, A.; Foroudi, P.; Seyyed Amiri, N.; Ezatabadipoor, E. How corporate social responsibility contributes to strengthening brand loyalty, hotel positioning and intention to revisit? Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1897–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Dokania, A.K.; Pathak, G.S. The influence of green marketing functions in building corporate image: Evidences from hospitality industry in a developing nation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2178–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G. The effects of hotel green business practices on consumers’ loyalty intentions: An expanded multidimensional service model in the upscale segment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3787–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.; Altinay, L.; Farmaki, A.; Kenebayeva, A.; Gursoy, D. Hotels’ sustainability practices and guests’ familiarity, attitudes and behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1063–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, X. Social responsibility and reputation influences on the intentions of Chinese Huitang Village tourists: Mediating effects of satisfaction with lodging providers. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1750–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Jang, J.; Kandampully, J. Application of the extended VBN theory to understand consumers’ decisions about green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Hsu, M.; Chen, X. How does perceived corporate social responsibility contribute to green consumer behavior of Chinese tourists: A hotel context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 3157–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, M.R.; Díaz-Fernández, M.C.; Font, X. Factors influencing willingness of customers of environmentally friendly hotels to pay a price premium. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 32, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A.; Lucchetti, M.; Ali, F. The impact of green practices in coastal tourism: An empirical investigation on an eco-labelled beach club. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.J.; Loi, R.; Chow, C.W. Can taking charge at work help hospitality frontline employees enrich their family life? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The effect of CSR on corporate image, customer citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. What influences water conservation and towel reuse practices of hotel guests? Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhouri, A.; Chaudhary, R. Employee perspective on CSR: A review of the literature and research agenda. J. Glob. Responsib. 2019, 10, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlek, M.; Tuna, M. Corporate social responsibility and work engagement: Evidence from the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zientara, P.; Kujawski, L.; Bohdanowicz-Godfrey, P. Corporate social responsibility and employee attitudes: Evidence from a study of Polish hotel employees. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 859–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.L.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M.; Kwon, N. The effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on employee well-being in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1584–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and organizational psychology: An integrative review. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Hon, A.H.; Chan, W.; Okumus, F. What drives employees’ intentions to implement green practices in hotels? The role of knowledge, awareness, concern and ecological behaviour. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Lee, S. Self-discipline or self-interest? The antecedents of hotel employees’ pro-environmental behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1457–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.-W. Making innovation happen through building social capital and scanning environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 56, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, A.; Stergiou, D.P. Corporate social responsibility and employee moral identity: A practice-based approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2554–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koburtay, T.; Syed, J.; Haloub, R. Congruity between the female gender role and the leader role: A literature review. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, M.D.; Vaca-Acosta, R.M.; Vargas-Sánchez, A. Socially Responsible Practices in Hotels: A Gender Perspective. In Corporate Social Responsibility in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gamor, E.; Amissah, E.F.; Boakye, K.A.A. Work–family conflict among hotel employees in Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis, Ghana. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Mirzapour, M.; Henderson, J.C.; Richardson, S. Corporate social responsibility and hotel performance: A view from Tehran, Iran. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. CSR and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment in hotel industry: The moderating roles of corporate entrepreneurship and employee attachment style. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2867–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singjai, K.; Winata, L.; Kummer, T.-F. Green initiatives and their competitive advantage for the hotel industry in developing countries. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, A.; Kilic, M.; Koseoglu, M.A.; Kuzey, C.; Karaman, A.S. The link among board characteristics, corporate social responsibility performance, and financial performance: Evidence from the hospitality and tourism industry. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Majid, A.; Yasir, M.; Qudratullah, H.; Ullah, R.; Khattak, A. Participation of hotel managers in CSR activities in developing countries: A defining role of CSR orientation, CSR competencies, and CSR commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H.; Lin, C.-P. The impact of corporate charitable giving on hospitality firm performance: Doing well by doing good? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 47, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-M.; Kim, W.G.; Kim, Y.J.; Agmapisarn, C. Hotel environmental management initiative (HEMI) scale development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, J.-S.; Trang, H.L.T.; Kim, W. Water conservation and waste reduction management for increasing guest loyalty and green hotel practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, H.; Morrison, A.M. The impacts of corporate social responsibility on organization citizenship behavior and task performance in hospitality: A sequential mediation model. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2582–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers-Rubio, R.; Casado-Díaz, A.B. Analyzing hotel efficiency from a regional perspective: The role of environmental determinants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-H.J.; Chen, C.-D. Does sustainability index matter to the hospitality industry? Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xie, J. Uncovering the effect of environmental performance on hotels’ financial performance: A global outlook. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2849–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sturman, M.C.; Wang, C. The motivational effects of pay fairness: A longitudinal study in Chinese star-level hotels. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.L.; Rhou, Y.; Uysal, M.; Kwon, N. An examination of the links between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its internal consequences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 61, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Park, J.; Wen, J. General managers’ environmental commitment and environmental involvement of lodging companies: The mediating role of environmental management capabilities. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1499–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W. Energy benchmarking in support of low carbon hotels: Developments, challenges, and approaches in China. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1130–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Okumus, F.; Chan, W. What hinders hotels’ adoption of environmental technologies: A quantitative study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.W.; Li, D.; Mak, B.; Liu, L. Evaluating the application of solar energy for hot water provision: An action research of independent hotel. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.; Lee, S.-C.; Hon, A.; Liu, L.; Li, D.; Zhu, N. Management learning from air purifier tests in hotels: Experiment and action research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, B.L.; Chan, W.W.; Li, D.; Liu, L.; Wong, K.F. Power consumption modeling and energy saving practices of hotel chillers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos, L.M.; Mejia, C.; Ozturk, A.B.; Wang, Y. A technology adoption and implementation process in an independent hotel chain. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröschl, S. Presumed incapable: Exploring the validity of negative judgments about persons with disabilities and their employability in hotel operations. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Liao, S.; Van der Heijden, B.I.; Guo, Z. The effect of socially responsible human resource management (SRHRM) on frontline employees’ knowledge sharing. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3646–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Choi, J.; Bo-young, M. Codes of ethics, corporate philanthropy, and employee responses. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 39, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Lyu, Y.; Qiu, C. Sexual harassment and proactive customer service performance: The roles of job engagement and sensitivity to interpersonal mistreatment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Greening the hospitality industry: How do green human resource management practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixed-methods study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, R.; Zhang, T.C. Corporate social responsibility in international hotel chains and its effects on local employees: Scale development and empirical testing in China. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, C.; Morrison, A.M. The effect of corporate social responsibility on hotel employee safety behavior during COVID-19: The moderation of belief restoration and negative emotions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Rhou, Y.; Topcuoglu, E.; Kim, Y.G. Why hotel employees care about Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Using need satisfaction theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Milliman, J.; Lucas, A. Effects of CSR on employee retention via identification and quality-of-work-life. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1163–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, M.; Mattila, A.S. Corporate social responsibility and equity-holder risk in the hospitality industry. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Ling, Q.; Luo, Z.; Wu, X. Why does empowering leadership occur and matter? A multilevel study of Chinese hotels. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez García de Leaniz, P.; Herrero Crespo, Á.; Gómez López, R. Customer responses to environmentally certified hotels: The moderating effect of environmental consciousness on the formation of behavioral intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mombeuil, C.; Fotiadis, A.K. Assessing the effect of customer perceptions of corporate social responsibility on customer trust within a low cultural trust context. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Zhang, P.; Guo, Y. Does a leader’s “partiality” affect employees’ proactivity in the hospitality industry? A cross-level analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Kozak, M.; Wen, J. Seeing the invisible hand: Underlying effects of COVID-19 on tourists’ behavioral patterns. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H. Effects of biophilic design on consumer responses in the lodging industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Song, H.; Lee, C.-K.; Lee, J.Y. The impact of four CSR dimensions on a gaming company’s image and customers’ revisit intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 61, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, C.K.; Schwepker, C.H. Enhancing the lodging experience through ethical leadership. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 669–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Lee, K.; Lee, S. Effects of corporate social responsibility on employees in the casino industry. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; McGinley, S.; Choi, H.-M.; Agmapisarn, C. Hotels’ environmental leadership and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.-C.; Lu, A.C.C.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Fang, C.-H. Ethical work climate, organizational identification, leader-member-exchange (LMX) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB): A study of three star hotels in Taiwan. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 32, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zientara, P.; Zamojska, A. Green organizational climates and employee pro-environmental behaviour in the hotel industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1142–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry (European Commission). Responsible Entrepreneurship: A Collection of Good Practice Cases among Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises across Europe; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Dinan, C. Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Hillier, D.; Comfort, D. Sustainability in the global hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Leonidou, C.N.; Fotiadis, T.A.; Zeriti, A. Resources and capabilities as drivers of hotel environmental marketing strategy: Implications for competitive advantage and performance. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-X.; Hu, Z.-P.; Liu, C.-S.; Yu, D.-J.; Yu, L.-F. The relationships between regulatory and customer pressure, green organizational responses, and green innovation performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3423–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacari, C.; Séraphin, H.; Gowreesunkar, V.G. Sustainable development goals and the hotel sector: Case examples and implications. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, 13, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Mozos, E.; García-Muiña, F.E.; Fuentes-Moraleda, L. Application of ecosophical perspective to advance to the SDGs: Theoretical approach on values for sustainability in a 4S hotel company. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Mozos, E.; García-Muiña, F.E.; Fuentes-Moraleda, L. Sustainable strategic management model for hotel companies: A multi-stakeholder proposal to “walk the talk” toward SDGS. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.H.; Hassan, T.H.; El Dief, M.M. A description of green hotel practices and their role in achieving sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D. Sustainable development goals and the world’s leading hotel groups. Athens J. Tour. 2019, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sembajwe, G.; Spaeth, K.; Dropkin, J. The Clean Hotel Room: A Public Health Imperative. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodhanwala, S.; Bodhanwala, R. Exploring relationship between sustainability and firm performance in travel and tourism industry: A global evidence. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 18, 1251–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X. Exploring Factors of Corporate Social Responsibility in Luxury Hotels: The Case of Marriott Hotel. Bachelor’s Thesis, Wenzhou-Kean University, Wenzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, C.; Tang, I.L.F.; Chan, W. Waterfront Hotels’ Chillers: Energy Benchmarking and ESG Reporting. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracioli, L. Immigration, self-determination, and the brain drain. Rev. Int. Stud. 2015, 41, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulos, D.; Kyridis, A.; Zagkos, C.; Konstantinidou, Z. Brain Drain Phenomenon in Greece: Young Greek scientists on their Way to Immigration, in an era of “crisis”. Attitudes, Opinions and Beliefs towards the Prospect of Migration. J. Educ. Hum. Dev. 2014, 3, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, R.R. An African brain drain: Igbo decisions to immigrate to the US. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 2002, 29, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Lemke, M.K.; Hsieh, Y.-C.J. Understanding the effects of COVID-19 on the health and safety of immigrant hospitality workers in the United States. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, C. Empowering States to Set the Priority of Environmental Claims in Bankruptcy. J. Land Use Environ. Law 2015, 31, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Serra-Cantallops, A.; Peña-Miranda, D.D.; Ramón-Cardona, J.; Martorell-Cunill, O. Progress in research on CSR and the hotel industry (2006–2015). Cornell Hosp. Q. 2018, 59, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.Y.; Watters, C.; McCormack, G. Schemes of arrangement in Singapore: Empirical and comparative analyses. Am. Bankruptcy Law J. 2020, 94, 463. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, W.; Watters, C. Mandatory disclosure in corporate debt restructuring via schemes of arrangement: A comparative approach. Int. Insolv. Rev. 2021, 30, S111–S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palliyaarachchi, R. The rise of Uber and Airbnb: The future of consumer protection and the sharing economy. Compet. Consum. Law J. 2020, 28, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kenneth-Southworth, E.; Watters, C.; Gu, C. Entrepreneurship in China: A review of the role of normative documents in China’s legal framework for encouraging entrepreneurship. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2018, 6, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, C.G.; Feng, X.; Tang, Z. China overhauls work permit system for foreigners. Ind. Law J. 2018, 47, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, X.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Sustainability of heritage tourism: A structural perspective from cultural identity and consumption intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantallops, A.S.; Cardona, J.R.; Matarredonda, M.G. The impact of search engines on the hotel distribution value chain. Redmarka Rev. Acad. Mark. Apl. 2013, 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bartosik-Purgat, M.; Michał, S.; Michał, L. The Effects of Social Media Tools’ Usage in International Marketing Communication–Corporation Perspective. In Competition, Strategy, and Innovation; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 151–171. [Google Scholar]

- Schletz, M.; Cardoso, A.; Prata Dias, G.; Salomo, S. How can blockchain technology accelerate energy efficiency interventions? A use case comparison. Energies 2020, 13, 5869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; He, D.; Luo, M.; Choo, K.-K.R. A survey of blockchain applications in the energy sector. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 15, 3370–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Mukhuty, S.; Kumar, V.; Kazancoglu, Y. Blockchain technology and the circular economy: Implications for sustainability and social responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkowski, A. Blockchain, business supply chains, sustainability, and law: The future of governance, legal frameworks, and lawyers. Del. J. Corp. L 2018, 43, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajkowski, R.; Safin, K.; Stańczyk, E. The success factors of family and non-family firms: Similarities and differences. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, P.; Hsu, S.-W.; Lemanski, M. A threshold concept and capability approach to the cross-cultural contextualization of western management education. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 44, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemański, M.K. Reverse transfer of HRM practices from emerging market subsidiaries: Organizational and country-level influences. In Multinational Enterprises, Markets and Institutional Diversity; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; Volume 9, pp. 399–415. [Google Scholar]

- Arp, F.; Lemański, M.K. Intra-corporate plagiarism? Conceptualising antecedents and consequences of negatively perceived mobility of ideas. J. Glob. Mobil 2016, 4, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Risco, A.; Mlodzianowska, S.; Zamora-Ramos, U.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S. Green entrepreneurship intention in university students: The case of Peru. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2021, 9, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Unit of Analysis | Themes | Citation of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Firm-level research | organizational performance | e.g., [6,7,21,53,54,55,57,58,59,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104] |

| responsible practices | e.g., [9,17,28,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,42,43,44,77,105,106,107,108,109] | |

| Individual-level research | influence on employees | e.g., [37,46,79,80,81,87,89,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121] |

| influence on guests | e.g., [29,40,42,60,63,64,65,66,67,69,70,122,123,124,125,126,127,128] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, Y.; Watters, C.; Lemański, M.K. Responsible Management in the Hotel Industry: An Integrative Review and Future Research Directions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 17050. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417050

Liang Y, Watters C, Lemański MK. Responsible Management in the Hotel Industry: An Integrative Review and Future Research Directions. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):17050. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417050

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Yuan, Casey Watters, and Michał K. Lemański. 2022. "Responsible Management in the Hotel Industry: An Integrative Review and Future Research Directions" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 17050. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417050

APA StyleLiang, Y., Watters, C., & Lemański, M. K. (2022). Responsible Management in the Hotel Industry: An Integrative Review and Future Research Directions. Sustainability, 14(24), 17050. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417050