Why Are You Turning a Blind Eye to Fair Trade Coffee?—Focused on the Comparison between Korea and Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Coffee Market

2.2. Ethical Consumption: Fair Trade Coffee

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Method

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Reasons for Not Consuming and Producing FTC

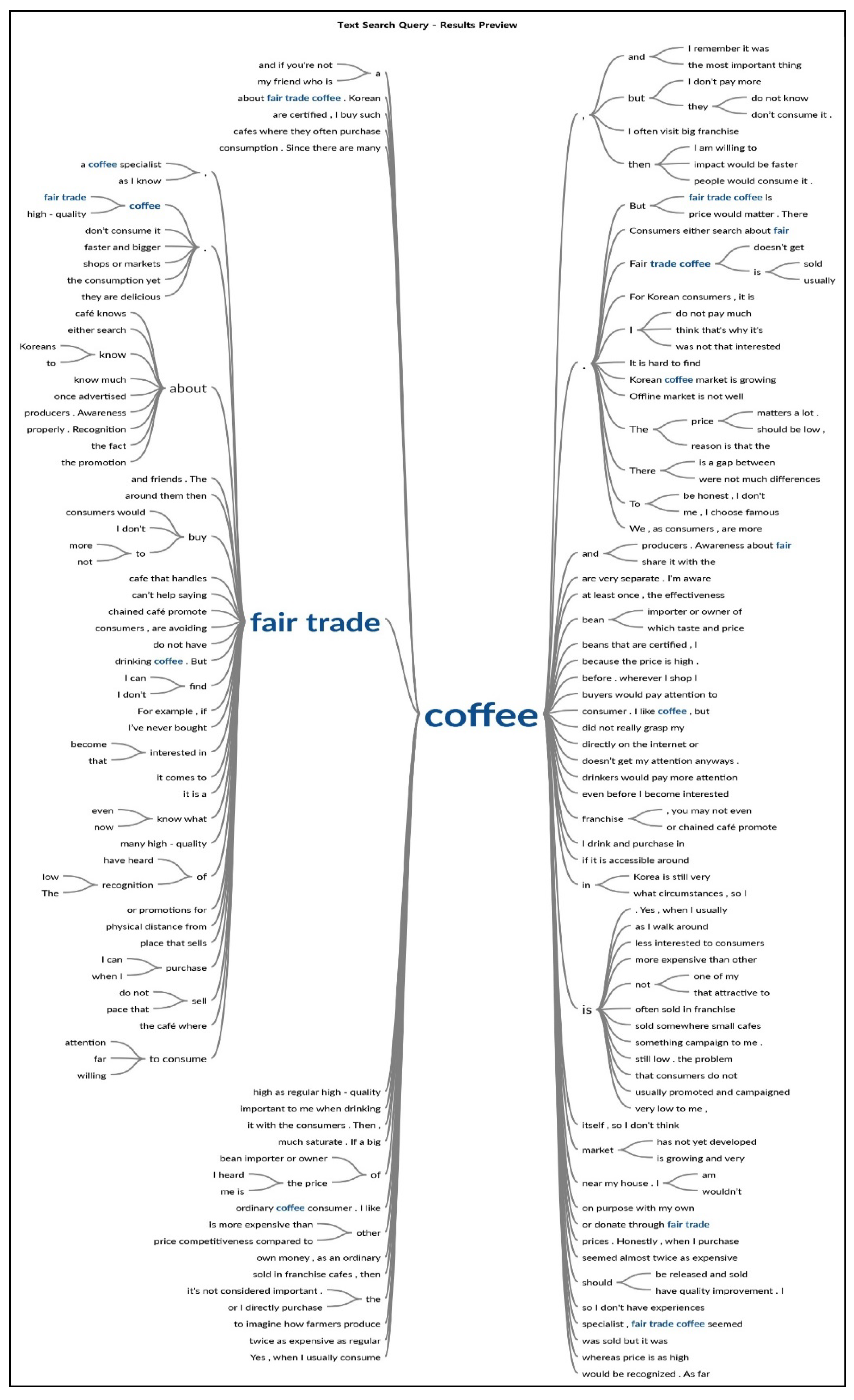

4.1.1. Case of Koreans

Consumer Side

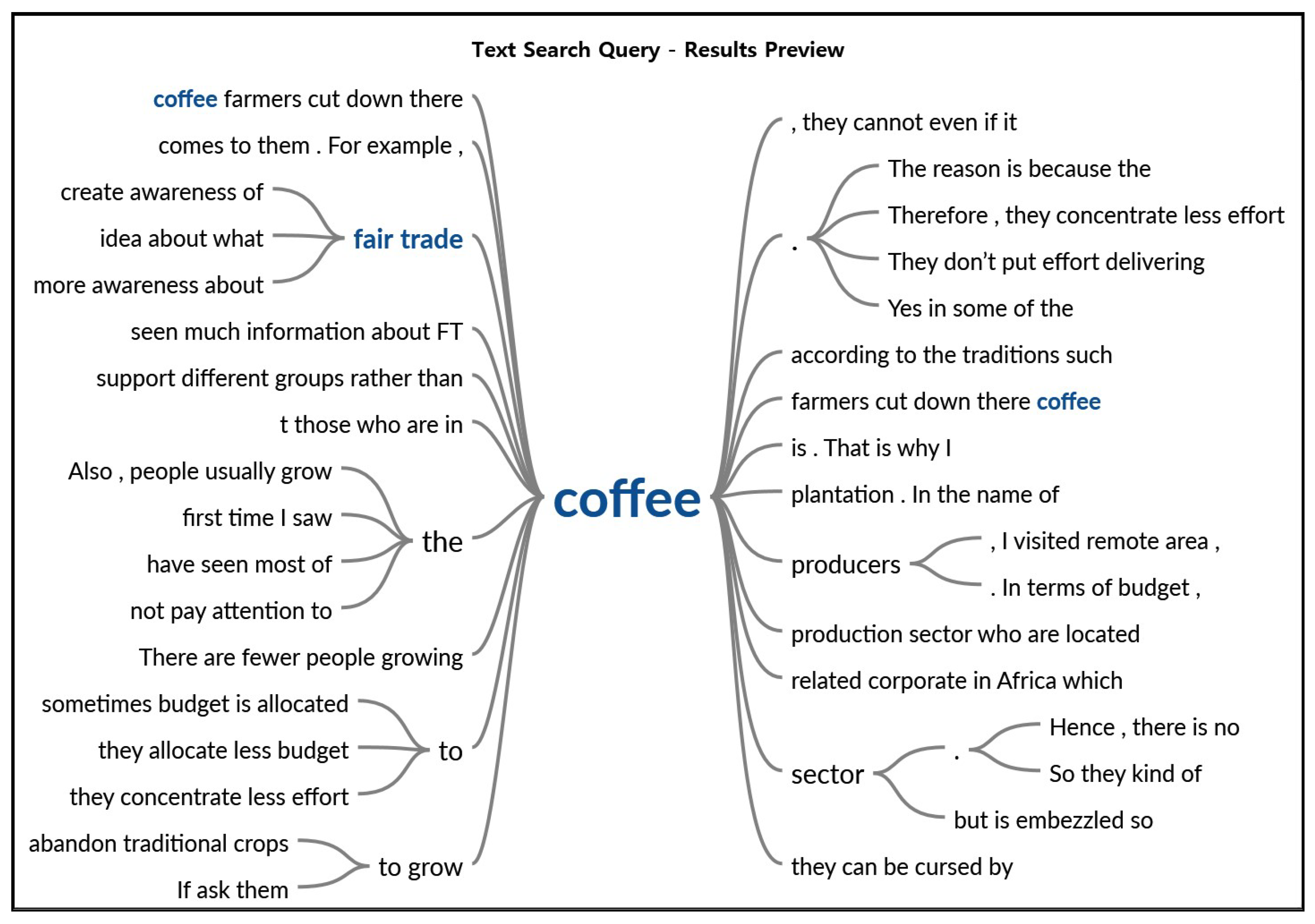

4.1.2. Case of Africans

Producer Side

Consumer Side

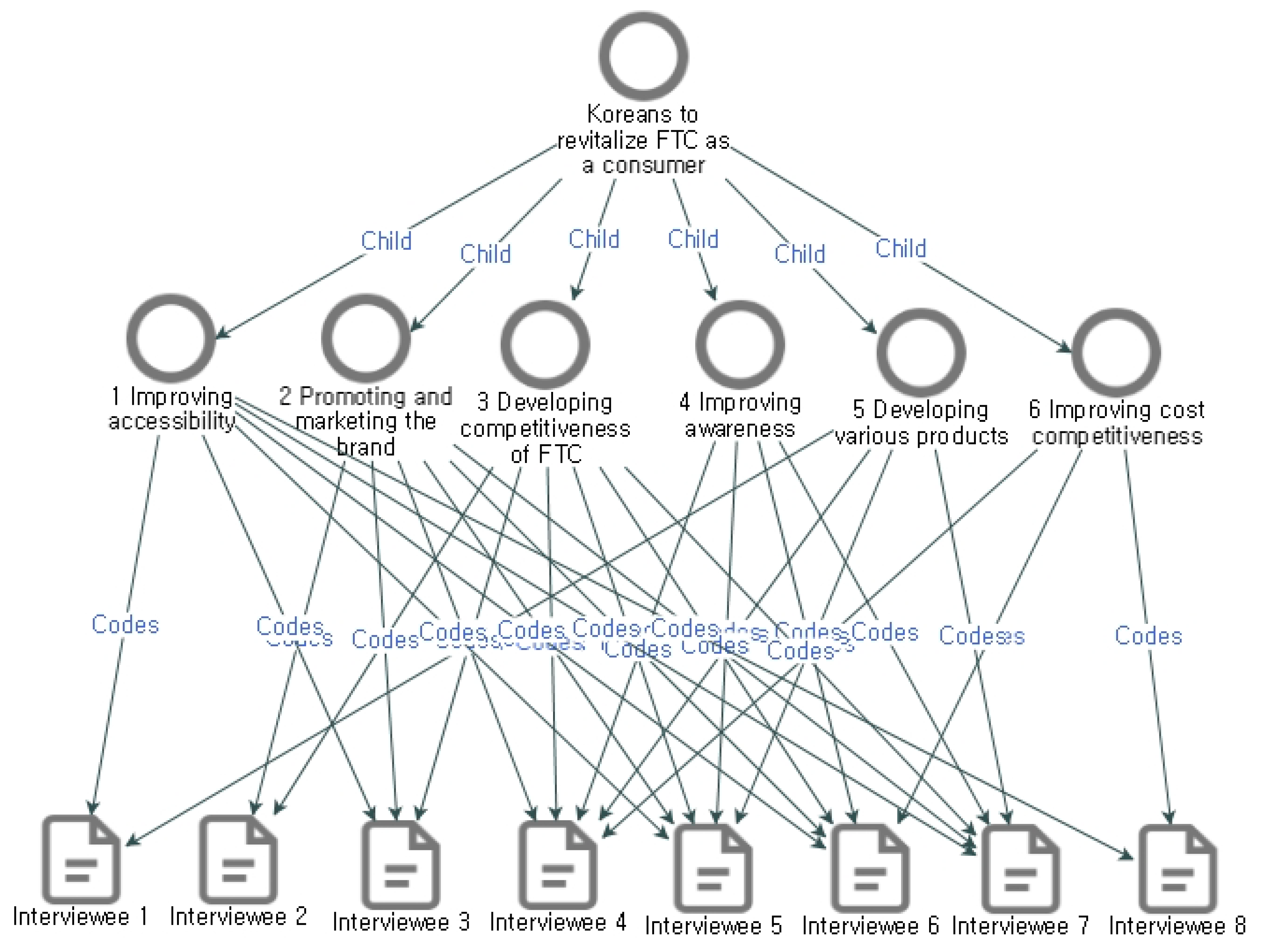

4.1.3. Revitalizing of FTC Market

Korean FTC Market

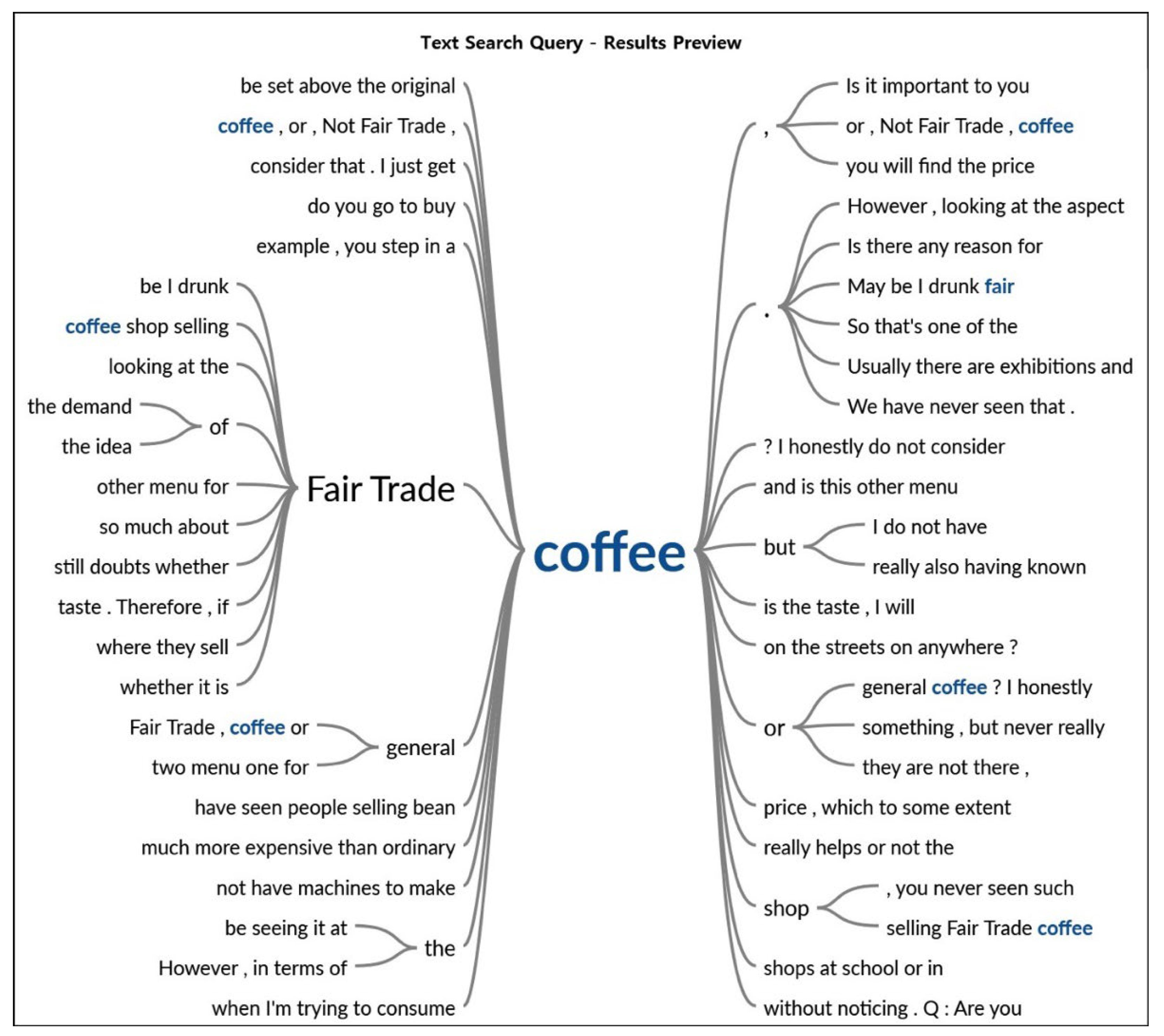

4.1.4. African FTC Market

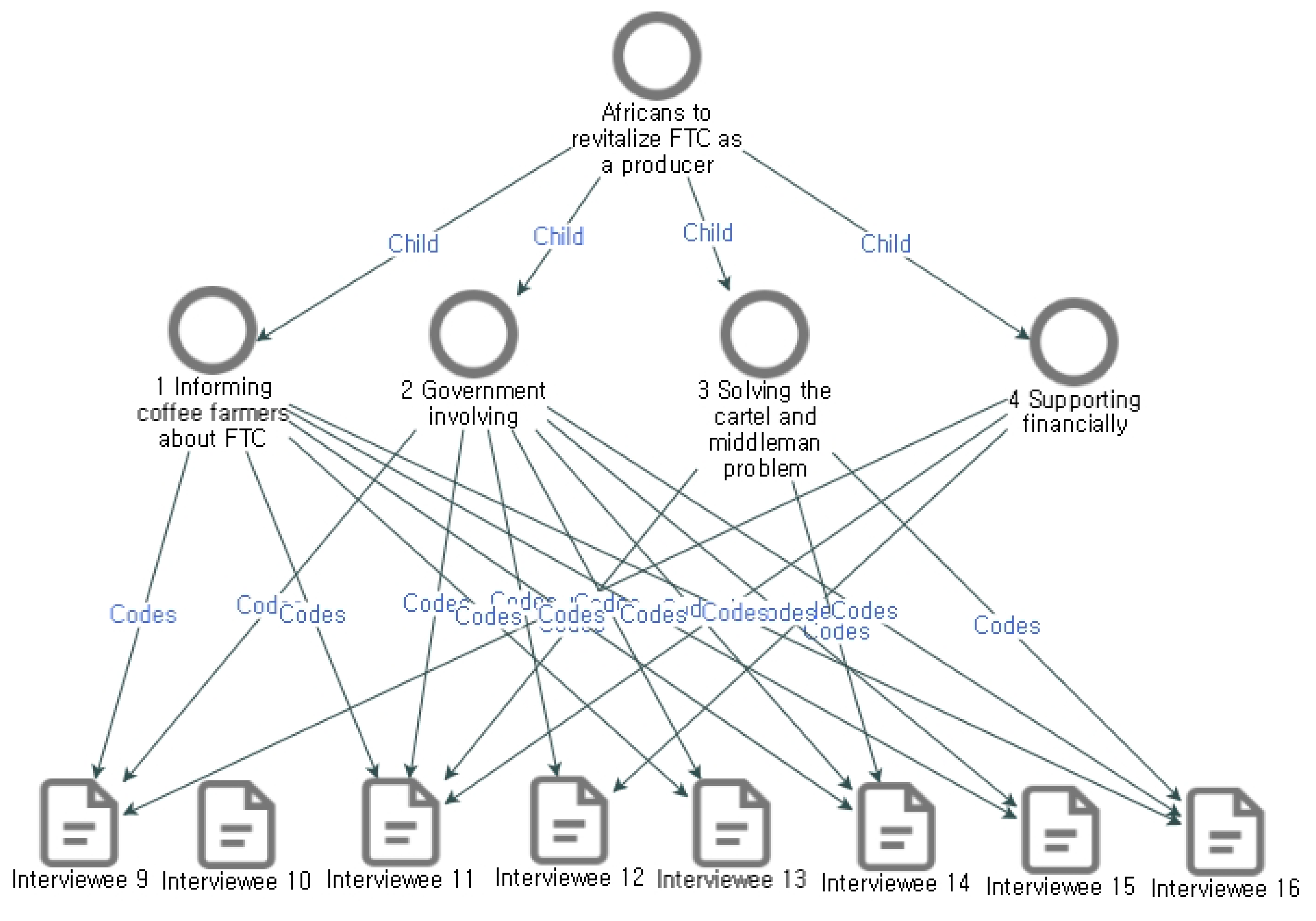

Producer Side

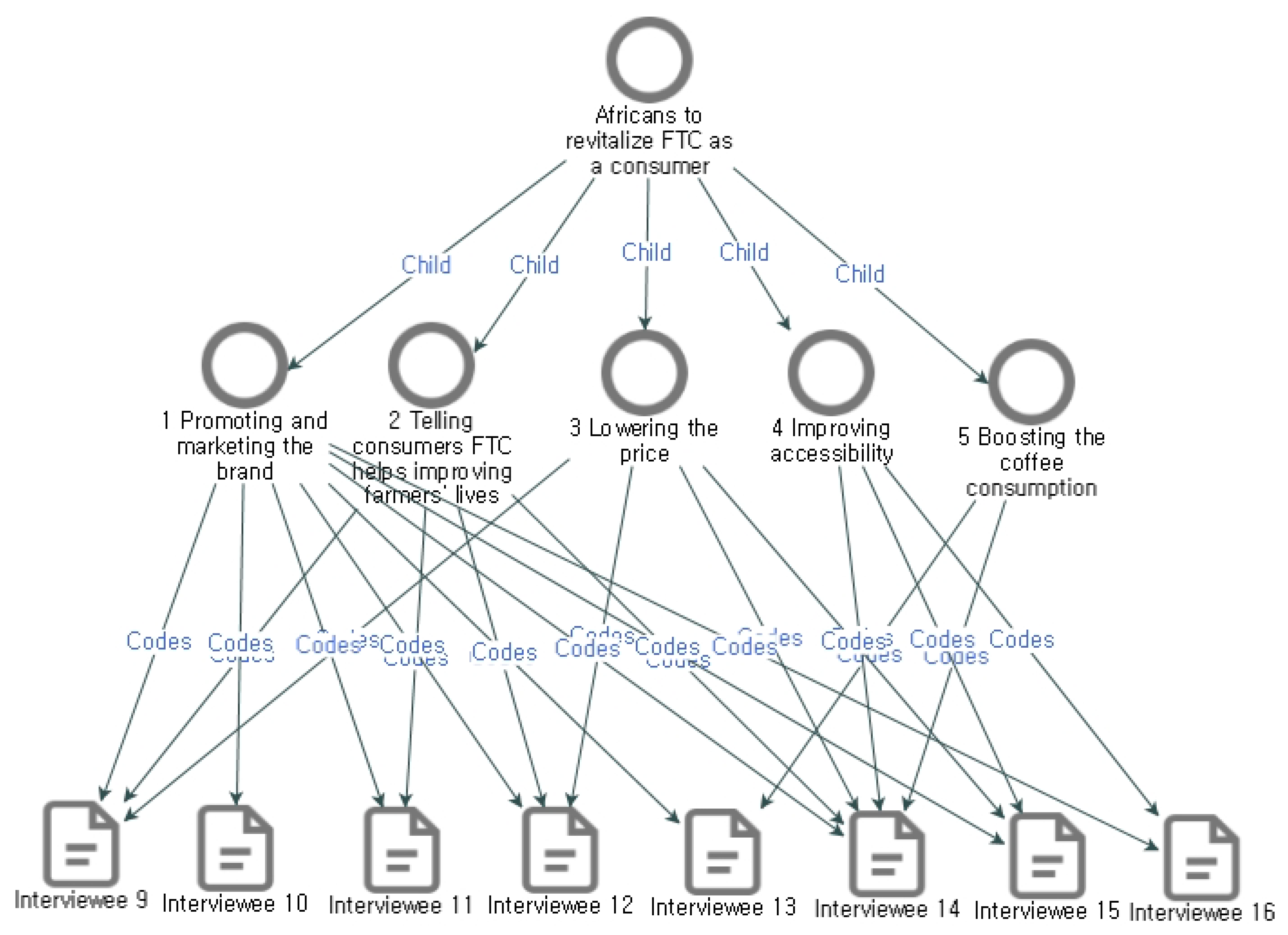

Consumer Side

5. Conclusion and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Contribution and Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samoggia, A.; Riedel, B. Consumers’ perceptions of coffee health benefits and motives for coffee consumption and purchasing. Nutrients 2019, 11, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mungai, C. Which African Countries Produce the Most Coffee; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- CABI. Promoting Domestic Coffee Consumption in Africa. 2022. Available online: https://www.cabi.org/projects/promoting-domestic-coffee-consumption-in-africa/ (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- International Coffee Organization. Historical Data on the Global Coffee Trade. 2020. Available online: https://www.ico.org/new_historical.asp (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Modor Intelligence. Africa Ready-To-Drink (Rtd) Coffee Market: Growth, Trends, COVID-19 Impact and Forecasts (2022–2027). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/africa-ready-to-drink-rtd-coffee-market (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Asia Exchange. Why Coffee Lovers Should Visit South Korea. 2021. Available online: https://asiaexchange.org/blogs/why-coffee-lovers-should-visit-south-korea/ (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Yoon, H.S.; Oh, S.K.; Yoon, H.H. The study on the influence of selection attributes for coffee shop on revisit intention: Based on customers of twenties and thirties. J. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 25, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.J.; Lee, Y.K. The effect of perceived value and subjective norm on satisfaction and behavior intention in franchise coffee shops. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 17, 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, A. Fair trade: Towards an economics of virtue. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 92, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G. Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair-trade coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 3, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillani, A.; Kutaula, S.; Leonidou, L.C.; Christodoulides, P. The impact of proximity on consumer fair trade engagement and buying behavior. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International. Power in Partnership. 2016. Available online: https://annualreport15-16.fairtrade.net/en/power-in-partnership/ (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Raynolds, L.T. Consumer/producer links in fair trade coffee networks. Sociol. Rural. 2002, 42, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A. Corporate social responsibility in the Coffee Sector: The Dynamics of MNC responses and code development. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgian Development Agency. Ethical Product Trends in South Africa 2013; Belgian Development Agency: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fairtrade International. Focus on Fair Trade Regions: Africa and the Middle East. Fair Trade Monitoring Report, 11th ed.; Fairtrade International: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Frommelt, J.; Ineichen, I.; Kaufmann, P.L.; Pollard, R.; Skolkin, S.L. The influence of fair trade labelled coffee on consumer perception and its impacts on small-scale producers. Group 2018, 151, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, N.R.; Kim, I.S. The structural relationships among consumers’ attitude by uncertainty, the norm and the purchase intention in a fair trade coffee context. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2017, 41, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.; Cheryl, M.; David, B. Mobilizing the ethical consumer in South Africa. Geoforum 2015, 67, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abong, G.O.; Omayio, D.G.; Elmah, G.; Marion, S. Consumer awareness, practices and purchasing behavior towards green consumerism in Kenya. East Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. 2021, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mokoena, L.G. Ethical tourism consumption: Should businesses be concerned? Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsu, S.K.; Zwick, D. Exploring consumer ethics in Ghana, West Africa. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizqiyanto, S. Starbucks’s fair trade in the edge of globalization. Etikonomi 2017, 16, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniku, A.C.; Akintimehin, O. Coffee culture: Will Nigerians drink coffee like others? Int. J. Humanit. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2021, 4, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyundai Research Institute. The five trends and prospects of the coffee industry-Growth to about 7 trillion won in the domestic coffee industry! Korean Econ. Rev. 2019, 848, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.H.; Hu, W.; Mupandawana, M.; Liu, Y. Consumer willingness to pay for fair trade coffee: A Chinese case study. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2012, 44, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.J. An analysis of the current status of Korea. Foodserv. Ind. Anal. Rep. 2018, 4, 1801. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.Y.; Kim, J.Y. A relationships among choice attributes, emotion, trust and long-term orientation associated with coffee-drinking. Food Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 12, 217–299. [Google Scholar]

- Barista News. 2021. Available online: http://baristanews.co.kr (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- National Assembly Newspaper. 2017. (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Kim, S. A study on the influence of the importance of coffee shop selection attribute and individual characteristics on the attitudes and behaviors of university students about coffee consumption. Foodserv. Ind. J. 2020, 16, 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. A study on the classification of selection attributes for franchise coffee shops by using the revised IPA. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2020, 26, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H. A study on the attributes of selecting coffee shop and type of coffee in relation to the reason for the visit: Focused on university students in Seoul and Gyeonggi province. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2016, 16, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Trade Centre. More from the Cup: Better Returns for East African Coffee Producers; International Trade Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- BrandsEye. Starbucks’ Entry into South Africa. Market Research; BrandsEye: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eco-Bank. Middle Africa Briefing Note; Eco-Bank: Lomé, Togo, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, L.D. Africa’s Coffee Consumption is Getting on the Rise. Coffee Business Initiative. 2017. Available online: https://coffeebi.com/2017/12/22/africas-coffee-culture-getting-rise/ (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- The New Economy. Coffee Culture Boons Kenya. 2022. Available online: https://www.theneweconomy.com/business/coffee-culture-boons-kenya (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Faria, J. Preference for Premium Coffee and Tea in African Countries 2018; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.H.; Kang, L.J. Study on the concept and practice of ethical consumption. J. Hum. Ecol. 2009, 18, 1047–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S. A study on the ethical consumption gap. The possibility of conversion of ethical purchase intention into behavior. Social enterprise for sustainable societies. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Social Enterprise, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 3–6 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth. Ethical Consumption is on the Rise in Africa; Environment: Sub-Saharan, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fairtrade International. Unlocking the Power: Annual Report 2012–13; Fairtrade International: Bonn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Godman, J. FLO Launches Marketing Initiative in Kenya Market; Cooperative News: Manchester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, M.; Goodman, M.; Hughes, A.; Barnett, C.; Clarke, N.; Cloke, P. Globalizing responsibility: The political rationalities of ethical consumption. Area 2013, 45, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairtrade Label South Africa. Fairtrade Sales in South Africa. 2015. Available online: http://www.fairtrade.org.za/news/entry/fairtrade-sales-in-south-africa (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- UNCTAD. Sustainability in the Coffee Sector: Exploring Opportunities for International Cooperation towards an Integrated Approach. Background Paper for Workshop; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, N.L.; Keith, B. The problem with fair trade coffee. Contexts 2014, 13, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haight, C. The problem with fair trade coffee. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2011, 3, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, C.; Neale, P. Conducting In-Depth Interviews: A Guide for Designing and Conducting In-Depth Interviews for Evaluation Input; Pathfinder International: Watertown, MA, USA, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M.; Lu, J. A quick look at NVivo. J. Electron. Resour. Libr. 2018, 30, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, C.; Mischo, W.H. Data management practices and perspectives of atmospheric scientists and engineering faculty. Issues Sci. Technol. Libr. 2016, 85, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.; Patricia, B. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ingenbleek, P.T.M.; Reinders, M.J. The development of a market for sustainable coffee in the Netherlands: Rethinking the contribution of fair trade. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 113, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schollenberg, L. Estimating the hedonic price for Fair Trade coffee in Sweden. Br. Food. J. 2012, 114, 428–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andorfer, V.A.; Ulf, L. Do information, price, or morals influence ethical consumption? A natural field experiment and customer survey on the purchase of Fair Trade coffee. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 52, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darian, J.C.; Tucci, L.; Newman, C.M.; Naylor, L. An analysis of consumer motivations for purchasing fair trade coffee. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2015, 27, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jo, M.; Ochieng, H.K.; Kim, J. Why Are You Turning a Blind Eye to Fair Trade Coffee?—Focused on the Comparison between Korea and Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 17033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417033

Jo M, Ochieng HK, Kim J. Why Are You Turning a Blind Eye to Fair Trade Coffee?—Focused on the Comparison between Korea and Africa. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):17033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417033

Chicago/Turabian StyleJo, Mina, Haggai Kennedy Ochieng, and Jisong Kim. 2022. "Why Are You Turning a Blind Eye to Fair Trade Coffee?—Focused on the Comparison between Korea and Africa" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 17033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417033

APA StyleJo, M., Ochieng, H. K., & Kim, J. (2022). Why Are You Turning a Blind Eye to Fair Trade Coffee?—Focused on the Comparison between Korea and Africa. Sustainability, 14(24), 17033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142417033