2. Methods

2.1. Research Context

Nosara is situated in the Nicoya canton in the province of Guanacaste on Costa Rica’s northern Pacific coast. Once a sleepy little town, Nosara has boomed in recent decades. In 2000, the town had a permanent population of just over 2900. Two decades later, the permanent population had grown by nearly 140 percent to almost 7000 permanent inhabitants. But this figure belies the true number of people in the community. In the last decade or so, Nosara has become a hot spot for the nearly 2 million tourists who visit the nation each year. Many attribute this marked uptick in tourism to three articles in

The New York Times since 2012 extolling the area’s virtues [

33,

34,

35]. To support the increase in tourism, developers and investors also have come to the area, building hotels, restaurants, and other service-providing facilities, many of which are staffed—at least in high season—by locals, Costa Ricans from other areas of the nation, and migrant workers. Residents, tourists, and visitors are attracted to the area’s beauty and lifestyle. Nosara is adjacent to Ostional National Wildlife Refuge, one of the world’s largest and most important turtle nesting sites [

1]. People flock to the area to witness this phenomenon and to take advantage of Nosara’s surf, yoga, arts, and cultural activities.

While undoubtedly beneficial in several ways, the community’s growth and development have raised several difficult issues about Nosara’s future [

2]. The key conflicts center on tourism and sustainable development—or how to balance social needs, economic development, and environmental protection. The problems in Nosara reflect a similar pattern seen in other tourist destinations: the influx of people and investment threaten the very ecological, historical, cultural, and other assets they came to experience in the first place [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. This has played out in Nosara in several ways. First, a lack of urban planning has resulted in uncontrolled growth fueled by tourism and local and foreign investment. Second, tourism-related development has not been accompanied by advances in infrastructure, in terms of both roads and public services (e.g., water, internet, electricity), resulting in inequities across areas and among locals. Third, the inequities of service access and delivery are exacerbated by local government corruption and discriminatory treatment that favors investors (both from San Jose and from international locations) over Guanacaste locals. Fourth, these problems cumulatively work against environmental, conservation, and biodiversity interests, often resulting in the degradation of critical habitat. Finally, despite the stated commitments of various parties to work toward sustainable development, misinformation, distrust, poor communication, weak coordination, and a general lack of governance hinders the ability of groups to work together and preserve what locals call Nosara’s “magic and harmony”.

Over the past several years, policymaking and regulatory efforts to address these and other issues have been delayed or blocked by loud objections—and occasional lawsuits—from various interest groups. The stakeholders in this conflict include [

2]: Developers and investors who want to build homes and facilities to support the growing numbers of tourists and residents; locals who want jobs and access to the amenities and services afforded to tourists and wealthy expats; expats and other wealthier residents who want to protect their investments and their quiet, laid-back lifestyles; and environmentalists who want to protect Ostional National Wildlife Refuge and other natural assets. The lack of policy and regulatory action coupled with continued growth have further entrenched these groups in their positions. The power imbalances are also highly problematic, with some transplants to the community possessing fortunes in the billions of dollars, compared to desperately poor Nicaraguan migrants, while locals and many others fall somewhere in between. However, potentially countering this problematic dynamic (or maybe further complicating it) is that the uber-wealthy expats in Nosara are far from united. Some arrived in Nosara decades ago when they saw it as beyond the reach of law-and-order and who largely want the town to remain isolated, its government weak, and its infrastructure less-than inviting. Others may be attracted to Nosara’s isolation, but desire better infrastructure and public services, nonetheless. And still other expats are clearly development minded and see Nosara as a place to make money.

The situation in Nosara came to our attention after some members of our research team completed a project implemented by INCAE Business School and the Latin American Center for Competitiveness and Sustainable Development that deployed the Social Progress Index (SPI) across various cantons in Costa Rica. The SPI uses a survey to measure numerous social, economic, and environmental indicators, which are amalgamated into three categories: basic human necessities, foundations of well-being, and opportunity (

www.socialprogress.org, accessed on 14 December 2022). In Nosara, the SPI was deployed at the household level and garnered more than 1000 responses.

On a 0 to 100 scale, Nosara scored 78.64 on basic human necessities, 66.11 on well-being, and 65.48 on opportunity. At a more nuanced level, the SPI results showed that Nosara (as compared to other areas of Costa Rica) has relatively high scores for nutrition, personal security, freedom of choice, and tolerance and inclusion, average scores for housing, access to information, healthcare and wellbeing, environmental quality, and personal rights, and low scores for access to higher education. Moreover, the results indicated four main concerns among the population: poor infrastructure, drug addiction and alcoholism, poverty, and unemployment.

These findings, coupled with the conflict situation in Nosara, inspired an INCAE-CLADS team member to conduct a more comprehensive study of Nosara with the goal of helping residents identify priorities for the community’s future. He asked Demo Lab, a nonprofit that works to foster democratic participation in the country, to fund the project and assembled a new team for the study, which includes three American researchers with expertise in public administration and participatory processes, environmental law, and communications and Q-methodology.

2.2. Q Methodology and Public Participation

The team developed a research design centered around Q methodology and public participation and aimed at helping to identify priorities for Nosara’s future. We identified Q as the appropriate method for this study for several reasons. First, as noted above, Q is a useful tool in SES research [

3,

4], and has found widespread application in sustainability studies [

12]. Second, Q is particularly useful for achieving aims such as those in this study. It helps identify and explain different perspectives on complex issues and has the potential to inform dialogue and policy action [

12,

15]. Finally, the steps of Q methodology afforded the use of public participation at multiple phases of the research project, which was important to the research team.

Specifically, we used public participation at three stages of the Q process: (1) We conducted interviews with community members, which helped educate and orient the team to the diversity of opinions in Nosara and were used to develop the concourse of potential Q-sort items. (2) We ensured that the Q-sort itself was completed by a diverse set of community members. (3) We held a community meeting where we presented the results of the Q study and led a facilitated deliberation process. The first two steps of our process mirror the steps in other Q research published in

Sustainability [

9,

29], while the third step demonstrates the value of Q for public dialogue.

2.3. The Nosara Interviews and Q-Sort

The interviews and Q-sort involved several steps. First, our local, bilingual team members set out to recruit interviewees, with the goal of getting participants from varied socio-economic backgrounds and with as much diversity of opinion as possible. Using a mix of purposeful and snowball sampling, we sought out residents who have always called Nosara home, disadvantaged immigrants from neighboring Nicaragua, as well as wealthier transplants from San Jose, the United States, and other locations abroad. That effort led to in-depth interviews with 67 stakeholders, conducted either in Spanish or English, based on the participant’s preference.

Second, we used an iterative, open-coding process to identify statements and issues from the interviews that captured the range of priorities for Nosara. These statements and issues were transformed into a 97-item Q concourse. The research team then conducted another iterative process to distill the concourse into the Q-sort, which included a sample of 37 statements about priorities for Nosara’s future (see

Appendix A). The instructions for the Q-sort asked participants to rank the 37 priorities on a grid ranging from −4 (least important) to +4 (most important). We also developed a brief post-sort survey that collected demographic information and asked for the rationale behind the participant’s choices for the most and least important priorities. The Q-sort and survey were made available in both Spanish and English.

Third, we launched the Q-sort and survey. We invited the interviewees to participate, and began a broader outreach effort using social media, fliers, emails, and direct outreach. This effort resulted in 79 completed Q-sorts.

Many of the same individuals participated in all or two of these data collection steps, though each step also engaged different individuals. Due to concerns about anonymity and respect for our human subject protocols, we did not gather data that would allow us to determine who participated in which steps. Moreover, for both the interviews and the sort itself, we had only loose criteria for inclusion and exclusion. We simply wanted as many people who live in Nosara for at least part of the year to complete the study, with an emphasis on recruiting poor and working-class residents we knew would be harder to engage.

Finally, we conducted centroid factor analysis with varimax rotation as is standard in Q methodology. We identified four factors, which we present in the results section. We then began preparing for the public dialogue.

2.4. Public Dialogue

We presented the results at a public meeting that included small-table, facilitated dialogue with 88 attendees. Again, all previous study participants were invited, with an open call for any other interested community members to join the deliberation. The meeting started with a brief overview of the Q study and its results, with a focus on consensus items, followed by a series of questions with which we wanted participants to wrestle: What are Nosara’s most important assets for addressing issues and challenges? What does sustainable development mean to you? What should be the first steps toward creating a sustainable development plan for Nosara?

To manage the conversation, participants were seated at tables with 8 to 12 others, along with a trained facilitator and a scribe to capture the conversation. Although we saw some advantages to bringing together Spanish and English speakers at the same tables, we decided it was more empowering to the participants if we put them at tables where the dialogue was conducted in their language of choice. The individual table facilitators were all bilingual and conducted the discussions at their tables in the language of choice identified by the participants. For event elements that involved the entire gathering rather than individual table activities, such as presentations and discussion set-ups, we provided simultaneous translation. Thus, when Costa Rican team members spoke, they used Spanish, which was translated into English, and when American team members spoke, they used English, which was translated into Spanish.

The public meeting generated additional data in the form of facilitator notes and a post-event questionnaire that collected demographic information about the meeting participants and asked about their satisfaction with the event and their perceptions of its efficacy. The questionnaire was completed by 52 of the 88 attendees. We discuss the survey results in the following section.

3. Results

In this section, we first present the results from the Q study and then present the results from the public dialogue.

3.1. Q Study Results

Of the 79 completed Q-sorts, 44 were completed in English and 35 in Spanish. The respondents included 32 women, 43 men, and 4 who did not indicate their gender. The mean age was 46.2 and the median age was 44.5 with a range from 20 to 72 years old. The participants self-identified into six categories 15 selecting as “locals” (indicating that they are from Nosara), 12 as Chepeño/Chepeña (meaning they are natives of the San Jose area who now live in Nosara), 34 as expat residents (meaning they are permanent or semi-permanent residents of Nosara, usually from the United States, Canada, and Europe, who possess privileged mobility [

39], 6 as foreign visitors (generally indicating that they either live in Nosara only part of the year or that they are migrants from other nations such as Nicaragua), 8 who selected “other”, and 4 who left the question blank. We chose these categories based on input from our Costa Rican team members and because these are the terms people use to identify themselves in Nosara.

The factor analysis revealed four factors, or distinct perspectives, about priorities for the future of Nosara.

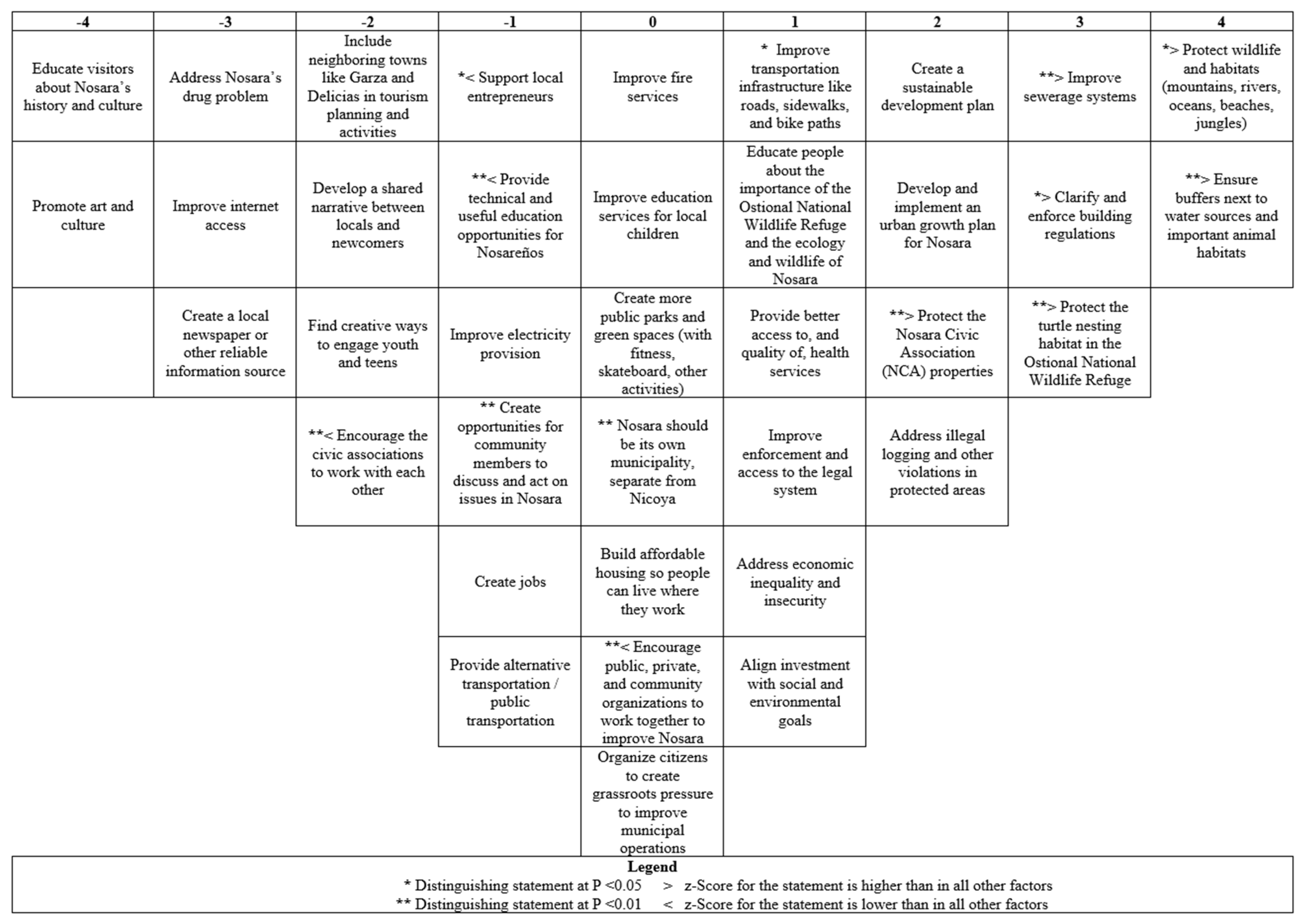

Appendix A shows a complete list of statements sorted, their z-scores, and their ranks within each factor. “Create a sustainable development plan” had the highest overall score of any statement and was ranked highly by all four factors.

Appendix B are the Q-factor diagrams. Each diagram is a Q-sort that best represents each factor. Each factor is also delineated below, with an exploration of our interpretation of the factors in the Discussion section. Four of the 79 participants did not load on any of the four factors, meaning their Q-sorts were unrelated to the others. All four were English speakers who identified as expats. Several participants were confounds, meaning they loaded on more than one factor. But in each of those cases, their factor loadings were significantly higher on one factor than the other, and so, for the analysis below, they are included as loading on the factor with which they were most strongly associated.

3.2. Factors

As noted above, the analysis revealed four factors, which we labeled Environmental Protection, Local Governance, Public Services, and Planning and Regulation. The four factors are moderately correlated with each other, with the strongest correlation between factors 1 and 4 (

Table 1). A correlation between the most similar factors below 0.5 suggests each factor represents a distinct perspective, despite their points of agreement. We discuss each factor individually below.

3.2.1. Factor 1: Environmental Protection

Thirty-one participants loaded on Factor 1, including a mix of expats and locals. The factor leaned heavily toward English-speaking expats, with 24 English speakers compared to 7 Spanish. Among the 31 participants, 20 identified as expats, 4 as Chepeño/Chepeña, 2 as locals, 2 as foreign visitors, 2 as other, and 1 blank. Participants who identified with the factor included 15 men, 15 women, and 1 who did not identify their gender (“other” was an option on the survey but not selected in this case). As we explore further in Discussion, the factor offered its strongest support for statements that emphasized environmental protection (

Table 2). Factor 1 saw drug abuse as less of a problem than the participants who loaded on other factors. They also tended to downplay issues that focused on education and information (

Table 3). See

Figure A1 for a graphical representation of the factor.

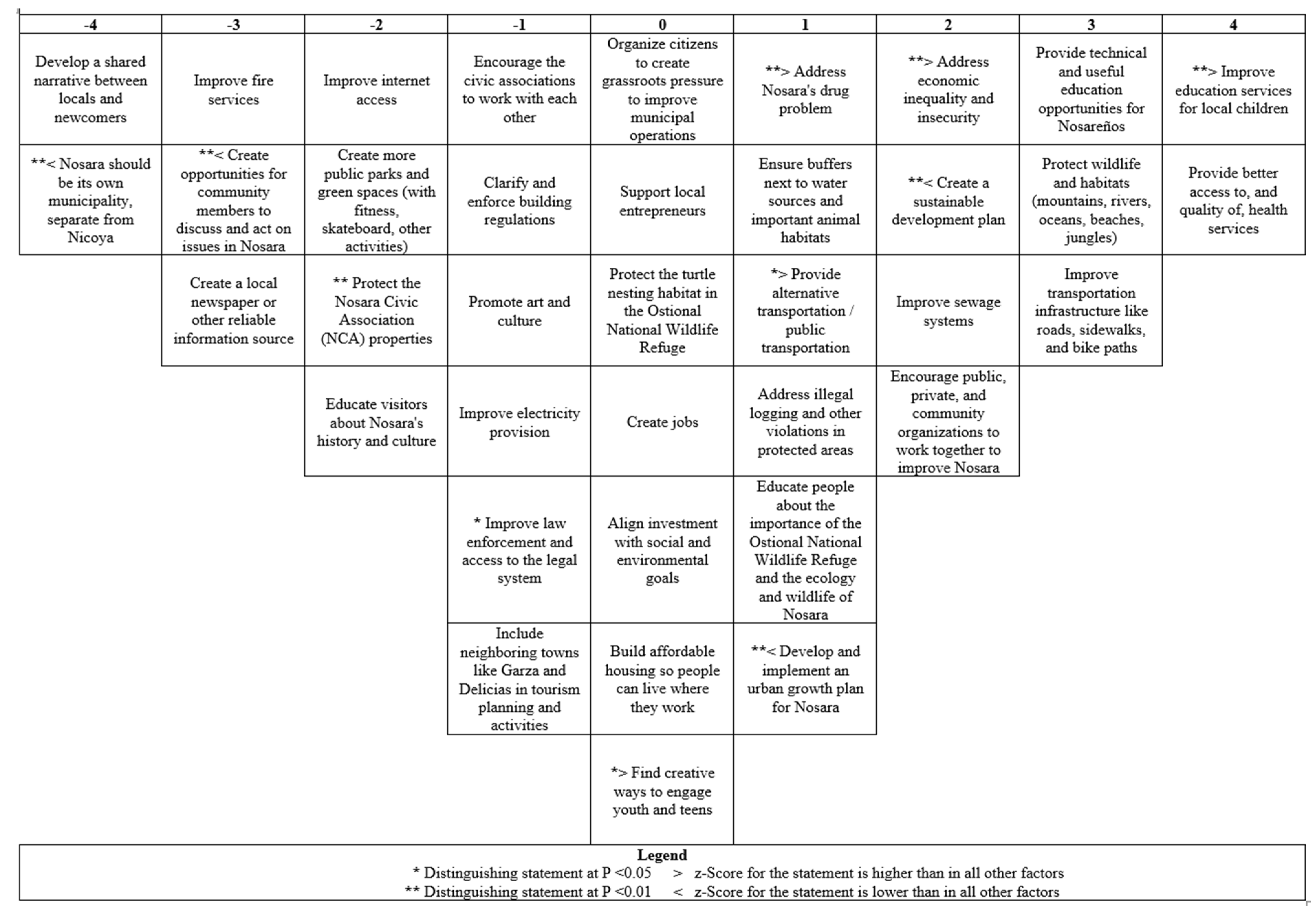

3.2.2. Factor 2: Local Governance

Nineteen participants loaded on Factor 2, including 10 Spanish speakers and 9 English speakers. Of these participants, 12 were men, 6 women, and 1 blank. In addition, the factor included 6 locals, 5 expats, 1 Chepeño/Chepeña, 3 foreign visitors, 3 others, and 1 blank. The factor offered its greatest support for government reform and government mechanisms such as a sustainable development plan (

Table 4). See

Figure A2 for a graphical representation of the factor.

Like Factor 1, the participants who loaded on Factor 2 did not see efforts to educate visitors as important (

Table 5). They also rejected the idea that the Nosara Civic Association (NCA) properties should be protected automatically. The NCA is an important-but-controversial organization in Nosara that arose from a lack of government and planning structures in the community to fulfill certain needs, including the purchase of important habitat that buffers the town center from its local beaches. However, distrust of the organization runs high in some circles, largely as a result of the significant amount of land it controls, including a swath that buffers the town’s main beach from its commercial and residential area. Residents told us that developers covet the property while environmentalists see it as crucial to protect. Uncertainty over the Association’s long-term plans for this land seems to fuel some of the tension within the community.

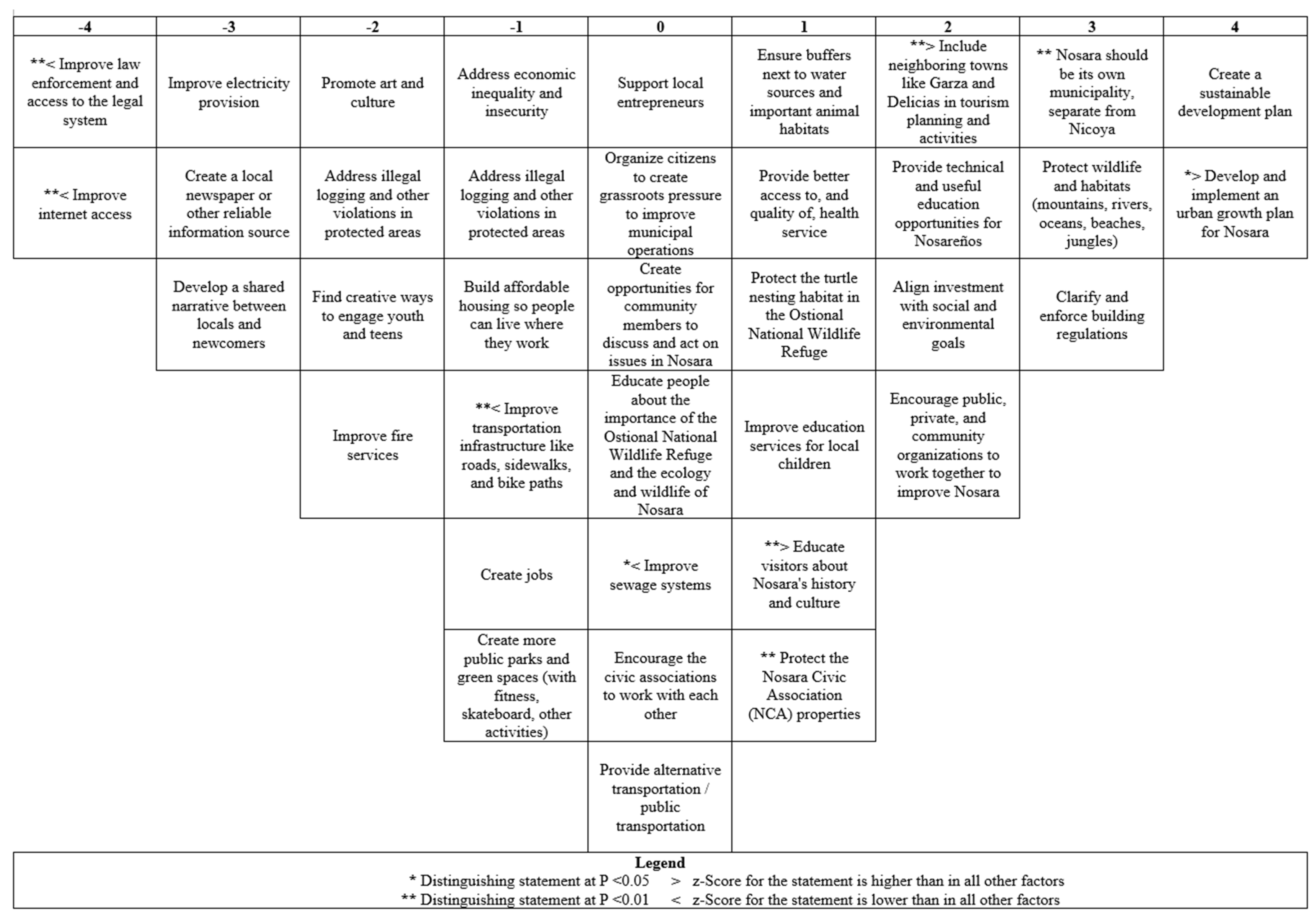

3.2.3. Factor 3: Public Services

Of the 18 participants who loaded on Factor 3, the majority were male (12) and Spanish-speaking (14). In addition, 4 English speakers and 4 women also loaded on Factor 3 (2 left gender blank), along with 6 participants who identified as Chepeño/Chepeña, 4 locals, 3 expats, 1 foreign visitor, 2 others, and 2 who left the question blank. The 18 participants who loaded on Factor 3 offered their strongest support for public services like education and health care (

Table 6) but rejected one of Factor 2’s most important statements—that Nosara should be its own municipality (

Table 7). See

Figure A3 for a graphical representation of the factor.

3.2.4. Factor 4: Planning and Regulation

Seven participants loaded onto Factor 4, including one who was negatively loaded, meaning their Q-sort expressed the inverse of the factor. Of those who loaded positively on the factor, 4 were Spanish speakers and 3 English speakers. Five were women, 1 was a man, and 1 blank. Two identified as locals, 2 as expats, 1 as Chepeño/Chepeña, 1 other, and 1 blank. The negative loader identified as a local. In Factor 4, we see an emphasis on planning, with both of its +4 statements focused on creating development plans and guidelines (

Table 8). The least supported statements for Factor 4 (

Table 9) tended to be those that focused on specific public services like law enforcement and electricity. See

Figure A4 for a graphical representation of the factor.

3.3. Distinguishing and Consensus Statements

To understand Q factors and assign meaning to them, it is helpful to look at each factor individually, as we have done above, as well as to examine them side by side, paying particular attention to the statements on which participants most agreed (

Table 10) and disagreed (

Table 11). In this case, the consensus statements illuminate items with little chance of success since most of them were either scored negative or neutral by the participants. The one true consensus item with no statistical difference in ranking between any of the factors was “create a local newspaper or other reliable source of information”. That statement had the lowest overall score of any statement in the study. “Create a sustainable development plan” did not rank in the top five consensus statements, but nonetheless managed the highest overall score (see

Appendix A), with each factor ranking it on the positive end of the spectrum, receiving a score of 2 for factors 1 and 3 and getting the top +4 score for factors 2 and 4. Therefore, it emerges as a more useful starting point to build toward a consensus action item than the statements that were ranked lower but more similarly between the factors. The top distinguishing statements really help delineate the differences in the factors, with Factor 3’s concern for education and the stark differences on whether Nosara should be its own municipality really standing out. So too does disagreement over the future status of the Nosara Civic Association properties.

3.4. Public Dialogue Results

The Q-sort respondents, as well as the broader community, were invited to discuss the Q study at a two-hour-long facilitated dialogue held on 29 July 2021. After a presentation about the Q-study results, the 88 attendees were led through a series of discussion prompts, including (1) What are Nosara’s most important assets for addressing issues and challenges? (2) What does sustainable development mean to you? (3) What should be the first steps toward creating a sustainable development plan for Nosara?

Given the animosity within the community and between specific groups, as well as the warnings we received about the need for security at the event, we were concerned about whether the public dialogue would be constructive. Few thought the meeting would go well, and even fewer thought consensus existed between Nosara’s various factions. However, the presentation of the Q results and our discussion of the commonality that existed among all factors—the need for a sustainable development plan—seemed to ease the tensions and generate dialogue. A lot of rich and interesting discussions occurred during the facilitated conversations, which were captured in notes by scribes. Most relevant here are the responses to the question, “what does sustainable development mean to you?” Unfortunately, due to privacy concerns and human-subject protocols, we cannot attribute specific comments to specific people or identify the stakeholder group(s) to which they belong. Nevertheless, the notes from the facilitators suggest common themes that emerged at the tables.

Not surprisingly, some participants expressed frustration and doubt about the possibilities for sustainable development. For example, one participant said. “Nicoya is for the Nicoyanos. They don’t care about us”. Another said, “There will be no equitable development due to economic issues”. (Note that many of these statements were made in Spanish and then translated by the bilingual table facilitators from their notes into English).

Most participants, however, were more positive. Some offered very specific responses that generally pointed to important elements in a sustainable development plan, such as “building inspections”, “land-use codes”, “water treatment”, “proper waste management”, and “regulatory codes and enforcement”.

Others emphasized the importance of leadership and governance in the development, implementation, and enforcement of a sustainable development plan. For example, participants said, we need “local governance with visible and tangible leadership”, “communication and conflict resolution through modern tools and approaches”, and “an established plan and an entity that regulates it in an equitable manner”. Some were more specific about the entities needed to oversee governance. For example, one said, “We need an organization that is legitimate and will be the main engine to push a plan forward”. Another asserted, “We need someone with a fixed salary to represent a sustainability plan and move it through the government structure. That could help create an organization that is based on what Nosara already has but is legitimate to represent many areas. And they are paid and committed to following up on the development of a sustainability plan”.

Others offered statements centered on a more general sustainability ethic. For example, one participant defined sustainable development as “How to develop and use social, economic, and environmental resources for the future”. Another participant stated, “A balanced sustainable progress management … works to keep the social-political and economic progress at the same pace”. Others suggested that sustainable development demanded a “balance between caring for resources and growing” and “Controlled growth taking into account environmental protection, efficiently using natural resources, including all social actors, and seeking the greatest economic benefit without detriment to the other two”.

At the conclusion of the dialogue, participants were asked to fill out a brief questionnaire about their experience, responding to a series of statements on a Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5) scale (see

Appendix B). Of the 88 people who attended the event, 52 completed the survey. The survey results show that 42 participants identified their language of choice as Spanish and 10 identified their language of choice as English. Ages ranged from 20 to 69 with an average age of 42. Thirty of the 52 respondents identified as men, 18 as women, 1 as other and 3 left the question blank. Seventeen identified as locals, 12 as expats, 11 as Chepeño/Chepeña, 3 as foreign visitors, 5 as other, and 4 left the question blank.

On average, participants felt the event helped them better understand the issues Nosara faces (M = 3.87) and, even more so, helped them understand how others think about the issues facing Nosara (M = 4.21). Participants gave the event’s representativeness of Nosara’s diversity moderately high scores (M = 3.87), although it is notable that this measure received one of the lowest scores in the survey. The highest scores were reserved for “the moderators/notetakers at the table were objective” (M = 4.62), and “I had an equal opportunity to participate in the table discussions” (M = 4.61). Participants indicated they enjoyed participating in the event (M = 4.42) and were willing to participate in a similar event in the future (M = 4.48). The responses to this last survey item, coupled with feedback from numerous meeting attendees, inspired the research team to continue its work in Nosara—a point we discuss further below.

4. Discussion

After learning about the situation in Nosara, our team set out to identify and understand the perceptions and beliefs in the community in hopes of finding areas of common ground that could serve as a basis to address previously intractable issues. The research project consisted of three steps: (1) in-depth interviews with 67 community members that helped us understand the issues and shape (2) a Q-sort completed by 79 community members, the results of which were presented at (3) a public dialogue attended by 88 community members. While the first two steps mirror those in several Q studies [

9,

40], the third step extends the application of Q to public dialogue.

While conducting the in-depth interviews necessary to build the concourse for the Q study, our bilingual research team picked up on a recurring theme: the acrimony that existed between various stakeholders about the future of Nosara. Just weeks before these interviews, a developer had sued to overturn the development plan Nosara had recently put in place. He and his supporters insisted they did so out of a concern for Nosara’s ecology, seeing the process of developing the plan as rushed and opaque, and therefore, incomplete, and open to challenges like his own. The developer, in interviews with the research team, positioned his lawsuit as a test case meant to strengthen rather than weaken the sustainable development apparatus. However, that is not the way others saw his lawsuit, as many viewed this legal action as a means for clearing a path for a project that would further degrade important habitats. The developer, meanwhile, reported getting death threats. Most people told us we would need security at our public event. Few thought consensus existed between Nosara’s various factions.

Our Q study results showed that the opposite was true. Indeed, four different perspectives emerged, one of which emphasized the value of natural habitat and the need to protect it, a second that centered on the mechanisms for protecting that habitat, a third that underscored the need for better local governance, and a fourth that focused on the need for better service provision from that government. Yet, participants, regardless of the perspective with which they identified, valued Nosara’s natural assets, wanted to see them protected, and, most of all, saw the value in creating a sustainable development plan in achieving that goal.

Given the acrimony, we saw the emergence of this consensus as an important place to start deliberations at the public meeting. At the meeting, we did the best we could to mix stakeholders with different perspectives, while also allowing for some self-selection based on language preference and personal comfort. We briefly presented the findings and had people explore their own relationship to the results, along with the other members of the small group to which they were assigned. Those discussions hinted to further potential for consensus in the community around what sustainable development means. Despite some skeptical comments, participants at each table identified specific elements that should be included in a sustainable development plan, as well as the need for leadership and governance that would balance the community’s environmental, economic, and social needs and assets.

We do not pretend that the public meeting allowed the participants—who in the small-town context of Nosara may have entrenched feelings about each other—to magically overcome their differences. Yet, our observations at the meeting coupled the with participants’ evaluation suggest that, at the very least, they were willing to hear each other out at this forum, that they learned something from the experience, and that they were willing to do it again.

We believe our use of Q—with interviews to inform the sort, its identification of distinct perspectives along with consensus items, and the presentation and discussion of results at a community meeting—helped make that possible. Specifically, the project occurred over several months, with interviews beginning in January 2021, the implementation of the Q-sort in June 2021, and the public meeting in July 2021. The longer-term duration of the project helped to build community awareness, momentum, and engagement. Furthermore, the Q-sort captured the varied needs, views, and interests of the community because it was based on interviews with diverse members of that community. In other words, the interviews enabled us to develop a Q-sort that directly reflected and spoke to community concerns. Of course, the value of Q in SES research, and particularly for participatory data collection efforts, is well recognized [

3,

4] and commonly used [

12].

However, beyond its ability to identify and explain different perspectives on complex issues, Q also is regarded for its potential to inform dialogue and policy action [

12,

15], though its application in such efforts is not seen frequently in research. Thus, our use of Q to shape a public dialogue is not only relatively novel, but also demonstrates its efficacy for such efforts. The presentation of the Q results, including areas of common ground, helped to overcome some of the bitterness and hostility among groups in Nosara. More specifically, the Q results enabled the research team—and more importantly—the community (and particularly those in the public dialogue) to navigate points of conflict, better understand and appreciate a diversity of perspectives and interests, and reframe different aspects of the problem. Moreover, the success of this effort is demonstrated by an invitation to the research team to return to Nosara and lead a participatory process aimed at coproducing an initial draft of a sustainable development plan. This work has already begun, with research conducted on local sustainable development plans, sketches of what such a coproduction effort might look like, and plans to recommence public engagement on this issue in spring 2023. Without the use of Q, it is unlikely that the research team—let alone the community—would have reached the point of coproducing a sustainable development plan.

In sum, the cumulative results of our project provide evidence that (1) citizens who have very different perspectives on the overall needs of a community may nonetheless share similar values and common ground—in this case the need for sustainable development; (2) the consensus items that emerge from a Q-methodological study can help create the conditions for constructive public dialogue and engagement; and (3) the combination of a Q study with a deliberative process can identify ways for a community in conflict to move forward.

Limitations

Some scholars and participants find the Q process time-consuming and demanding [

40]. It certainly took an enormous effort in the Nosara case, necessitating a local, bilingual team capable of first conducting the in-depth interviews, using those interviews to develop a concourse and ultimately the sort, and then getting diverse residents to complete the sort itself. Moreover, sorting Q statements takes time, patience, and at least a basic reading level if using textual statements, all of which are factors researchers should consider. However, like Sardo and Sinnett [

40], both the research team and the participants ultimately found the process to be thought provoking and the results to be useful for understanding the issues in Nosara. We also found the results to be useful for fostering public engagement and dialogue. It is unclear whether the Q results would prove as useful for public engagement in other contexts—especially ones where there might be less agreement on pivotal questions. However, we suspect the Q process and results could still provide important insights into the community under study and help inform engagement processes. Of course, this may not lead to a constructive and productive outcome in every instance.

A few other limitations are worth noting. It is possible that we missed a segment of the population in one or more stages of the processes, which could mean there are additional perspectives among the residents that we failed to reveal. If that is the case, then a door is opened for a segment of the population to reject the process, its findings, and the next steps. The bilingual, local team we engaged to conduct interviews and recruit participants are well connected to many aspects of Nosara and many types of people in the relatively small town. And by the numbers, they did a great job of recruiting diverse participants. However, by the very nature of their language skill, this group of hired research assistants occupies a privileged place in Nosara’s socio-economic hierarchy, which may have affected the willingness of certain populations to participate.

We also were constrained in other ways. Within Nosara, several clusters of residential development exist, each separated from the other by a few miles of often difficult roads. The wealthier clusters are closer to the beach, while most working-class people live in a town center further from the ocean. Our original intention was to have more than one public dialog so that we could engage people in multiple locations. However, COVID made that impossible as we were only able to identify a single establishment—in the wealthier part of town—that would allow us to host the meeting. It also remains unclear whether and how the research team will be successful in helping the community to build consensus around a coproduced sustainable development plan. We have done our best to be upfront with participants about our own limitations and to emphasize that they themselves need to drive the process while we provide help and expertise, including the provision of additional public dialogues as needed. Simply stated, without broad community buy-in and action, the efforts of the research team will have relatively little impact.