The Impact of Reading Anxiety of English Professional Materials on Intercultural Communication Competence: Taking Students Majoring in the Medical Profession

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Pragmatic Competence

2.2. Reading Anxiety with English Professional Materials

2.3. Effects of Reading Anxiety on Intercultural Communication

3. Research Questions

4. Research Methods

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Participants and Data Collection

4.3. Instruments

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Results and Discussions

5.1. The Development of RAEPMS and ICCS

5.1.1. The EFA and CFA in Developing RAEPMS

5.1.2. The EFA and CFA in Developing ICCS

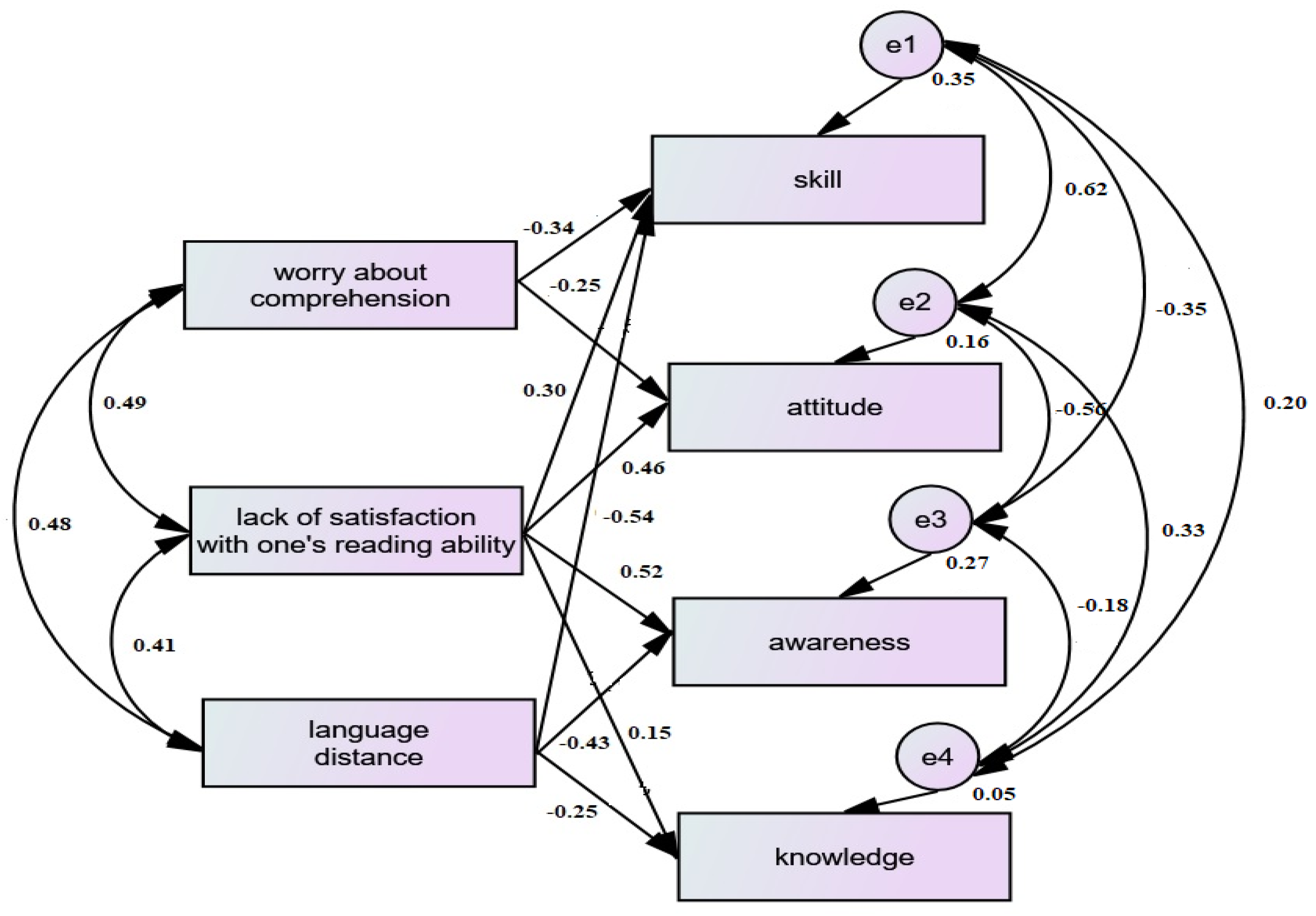

5.2. Impact of RAEPMS and ICCS (: What Is the Relationship between RAEPMS and ICCS?)

5.2.1. From “Worry about Comprehension” to ICC

5.2.2. From “Lack of Satisfaction with One’s Reading Ability” to ICC

5.2.3. From “Language Distance” to ICC

5.3. Pedagogical Implementation (: What Pedagogical Implementation Will Decrease Reading Anxiety in English Professional Materials and Increase ICC?)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. RAEPMS with CFA

| Item | Initial Item | Question |

| Factor 1: Worry about comprehension | ||

| 1 | 10 | I like to read English professional materials. (reverse question) |

| 2 | 12 | Once you get used to it, it is not so difficult to read English professional materials. (reverse question) |

| Factor 2: Lack of satisfaction in reading ability | ||

| 3 | 4 | I feel nervous when reading unfamiliar English professional materials. |

| 4 | 5 | When reading English professional materials, I feel nervous whenever I encounter grammar I don’t understand. |

| 5 | 3 | Whenever I see a full page of English professional materials, I get flustered. |

| Factor 3: Language distance | ||

| 6 | 11 | When I read English professional materials, I feel confident. (reverse question) |

| 7 | 16 | At present, I am satisfied with my English professional materials reading ability. (reverse question) |

Appendix B. ICCS with CFA

| Item | Initial Item | Question |

| Factor 1: Skill | ||

| 1 | 7 | I am able to properly interact and communicate with people from different cultural backgrounds in the workplace. |

| 2 | 15 | I can use English when communicating with people from other cultures. |

| 3 | 5 | When I meet people from different cultures, I am able to start conversations. |

| 4 | 10 | I can handle communication barriers due to different cultural backgrounds. |

| Factor 2: Attitude | ||

| 5 | 20 | I always try to get in touch with people from other cultures. |

| 6 | 21 | I would like to participate in cross-cultural events in the workplace. |

| 7 | 14 | I feel confident when interacting with people from different cultural backgrounds. |

| 8 | 12 | I am able to build cross-cultural friendships. |

| Factor 3: Awareness | ||

| 9 | 32 | My English is not good enough to communicate with people from other cultures. (reverse question) |

| 10 | 26 | I get overwhelmed when it comes to expressing myself in front of people from different cultures. (reverse question) |

| 11 | 27 | I find it difficult to make friends with people from different cultures. (reverse question) |

| Factor 4: Knowledge | ||

| 12 | 24 | I am eager to meet colleagues from different cultures and countries. |

| 13 | 22 | I would like to learn about education and training in different cultures or countries. |

References

- Kawar, T.I. Cross cultural differences in management. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, I.-C. English as a lingua franca (ELF) in intercultural communication: Findings from ELF online projects and implications for Taiwan’s ELT. Taiwan J. TESOL 2012, 9, 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. Cross-cultural pragmatic failure. Appl. Linguist. 1983, 4, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, D. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics, 4th ed.; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, G. Pragmatic transfer. Second. Lang. Res. 1992, 8, 203–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.R.; Kasper, G. Pragmatics in Language Teaching; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkel, E. When in Rome: Evaluations of L2 pragmalinguistic behaviors. J. Pragmat. 1996, 26, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinabadi, N.; Rezazadeh, M.; Shirinbakhsh, S. “I can learn how to communicate appropriately in this Language” Examining the links between language mindsets and understanding L2 pragmatic behaviours. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2021, 51, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, S. Correlation between college students’ pragmatic competence and intercultural sensitivity. Int. J. Cult. Hist. 2016, 2, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. Symbolic representation and attentional control in pragmatic competence. In Interlanguage Pragmatics; Kasper, G., Blum-Kulka, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. A mixed-methods study of computer-mediated communication paired with instruction on EFL learners’ pragmatic competence. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2022, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardovi-Harlig, K. Empirical evidence of the need for instruction in pragmatics. In Pragmatics in Language Teaching; Rose, K.R., Kasper, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. Adult Chinese as a second language learners’ willingness to Communicate in Chinese: Effects of cultural, affective, and linguistic variables. Psychol. Rep. 2017, 120, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Jackson, J. An exploration of Chinese EFL learners’ unwillingness to communicate and foreign language anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 2008, 92, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.-N. Shyness and EFL Learning in Taiwan: A study of Shy and Non-Shy College Students’ Use of Strategies, Foreign Language Anxiety, Motivation and Willingness to Communicate. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Jackson, J. Reticence in Chinese EFL students with varied proficiency levels. TESL Can. J. 2009, 26, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Doucette, J. Willingness to communicate and action control. System 2010, 38, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. Bilingual/multilingual learners’ willingness-to communicate in and anxiety on speaking Chinese and their associations with self-rated proficiency in Chinese. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2016, 21, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, E.K.; Horwitz, M.B.; Cope, J.A. Foreign language classroom anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 1986, 70, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.J. Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: What does language anxiety research suggest? Mod. Lang. J. 1991, 75, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, C. Factors of foreign language reading anxiety in a Taiwan EFL higher education context. J. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Res. 2017, 4, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bensalem, E. Foreign language reading anxiety in the Saudi tertiary EFL context. Read. A Foreign Lang. 2020, 32, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Gardner, R.C. The subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing in the second language learning. Lang. Learn. 1994, 44, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, V.D. Anxiety and reading comprehension in Spanish as a foreign language. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2000, 33, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.M.; Al-Saraj, T. Foreign language classroom anxiety of Arab learners of English: The effect of personality, linguistic and sociobiographical variables. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2015, 5, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaith, G.M. Foreign language reading anxiety and metacognitive strategies in undergraduates’ reading comprehension. Issues Educ. Res. 2020, 30, 1310–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, K.A. Intercultural Communication and Foreign Language Anxiety. Master’s Thesis, The Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, Y.; Horwitz, E.K.; Garza, T.J. Foreign language reading anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 1999, 83, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghi, M. An instrument for EFL reading anxiety: Inventory construction and preliminary validation. J. Asia TEFL 2012, 9, 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Q.; Vibulphol, J. English as a foreign language reading anxiety of Chinese university students. Int. Educ. Stud. 2021, 14, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustig, M.W.; Koester, J.; Zhuang, E. Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication Across Cultures; Pearson and AB: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rathje, S. Intercultural competence: The status and future of a controversial concept. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2007, 7, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Al-Shbou, M.; Nordin, M.; Abdul Rahman, Z.; Burhan, M.; Madarsha, K. The potential sources of foreign language reading anxiety in a Jordanian EFL context: A theoretical framework. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2013, 6, 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- University of Minnesota. Communication in the Real World. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing Edition. 2016. Available online: https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/chapter/8-4-intercultural-communication-competence/ (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Van Ek, J. Objectives for Foreign Language Learning; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, R.L. The effects of an internationalized university experience on domestic students in the United States and Australia. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2010, 14, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, S.; Gobel, P. Anxiety and predictors of performance in the foreign language classroom. System 2004, 32, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazykhankyzy, L.; Alagözlü, N. Developing and Validating a Scale to Measure Turkish and Kazakhstani ELT Pre-Service Teachers’ Intercultural Communicative Competence. Int. J. Instr. 2019, 12, 931–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byram, M. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. A further note on tests of significance in factor analysis. Br. J. Psychol. 1951, 4, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, B.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.-H.R. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, A.; Dillon, W.R. A simulation study to investigate the use of cutoff values for assessing model fit in covariance structure models. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. Application of structural equation modeling to evaluate customer satisfaction in the China internet bank sector. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Instrumentation, Measurement, Circuits and Systems (ICIMCS 2011), Hong Kong, China, 12–13 December 2011; pp. 975–978. [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N.K. Pesquisa de Marketing: Uma Orientação Aplicada, 6th ed.; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M. Structural Equation Modeling and Regression: Guidelines for Research Practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, H.P. Logic and Conversation. In Speech Acts [Syntax and Semantics 3]; Cole, P., Morgan, J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C. Practitioner review: The assessment of language pragmatics. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2002, 43, 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrison, C.; Ernst-Slavit, G. From Silence to a Whisper to Active Participation: Using Literature Circles with ELL Students. Read. Horiz. 2005, 46, 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z.; Kormos, J. The role of individual and social variables in oral task performance. Lang. Teach. Res. 2000, 4, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, L. Fundamental Considerations in Language Testing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Halt, D.; Lapkin, S.; Swain, M. Communicative language tests: Perks and Perils. Eval. Res. Educ. 1987, 1, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Canale, M.; Swain, M. Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Appl. Linguist. 1980, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slangen, A.L. A communication-based theory of the choice between greenfeld and acquisition entry. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1699–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschan-Piekkari, R.; Zander, L. Language and Communication in International Management; ME Sharpe: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barner-Rasmussen, W.; Aarnio, C. Shifting the faultlines of language: A quantitative functional-level exploration of language use in MNC subsidiaries. J. World Bus. 2011, 46, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschan, R.; Welch, D.; Welch, L. Language: The forgotten factor in multinational management. Eur. Manag. J. 1997, 15, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, J. Consumer language preferences in service encounters: A cross-cultural perspective. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2011, 21, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, J.; Van Vaerenbergh, Y.; Grönroos, C. Consumer willingness to communicate in a second language: Communication in service settings. Manag. Decis. 2014, 52, 950–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vaerenbergh, Y.; Holmqvist, J. Examining the relationship between language divergence and word-of-mouth intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barner-Rasmussen, W.; Ehrnrooth, M.; Koveshnikov, A.; Mäkelä, K. Cultural and language skills as resources for boundary spanning within the MNC. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 886–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kor, P.P.K.; Liu, J.Y.W.; Kwan, R.Y.C. Exploring nursing students’ learning experiences and attitudes toward older persons in a gerontological nursing course using self-regulated online enquiry-based learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods study. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 111, 105301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, L.; Reis, S.; Coelho, F. Preferences for studying materials: What has COVID-19 changed. In Proceeding of the 2021 4th International Conference of the Portuguese Society for Engineering Education (CISPEE), Lisbon, Portugal, 21–23 June 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, G.; Rose, K. Pragmatic Development in a Second Language; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer, D.; Pickering, L. Problems in the presentation of speech acts in ELT materials: The case of complaints. ELT J. 1995, 49, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpis, L.H.; Hunter, J. Developing students’ cultural intelligence through an experiential learning activity: A cross-cultural consumer behavior interview. J. Mark. Educ. 2017, 39, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelechoski, A.D.; Riggs Romaine, C.L.; Wolbransky, M. Teaching psychology and law: An empirical evaluation of experiential learning. Teach. Psychol. 2017, 44, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.N.; Nakayama, T.K. Intercultural Communication in Contexts, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; p. 465. [Google Scholar]

- The University of Rhode Island, Human Subjects Protections: Does My Research Need IRB Review? Available online: https://web.uri.edu/research-admin/office-of-research-integrity/human-subjects-protections/does-my-research-need-irb-review/ (accessed on 31 May 2022).

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | AVE | Cronbach Alpha | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.749 | 0.562 | 0.706 | 0.716 | ||

| 0.078 | 0.836 | 0.699 | 0.873 | 0.874 | |

| 0.679 ** | −0.560 | 0.759 | 0.576 | 0.711 | 0.727 |

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | AVE | Cronbach Alpha | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skill | 0.765 | 0.585 | 0.858 | 0.849 | |||

| Attitude | 0.757 ** | 0.765 | 0.585 | 0.869 | 0.848 | ||

| Awareness | −0.452 ** | −0.558 ** | 0.806 | 0.649 | 0.839 | 0.847 | |

| Knowledge | 0.456 ** | 0.649 ** | −0.341 ** | 0.737 | 0.543 | 0.748 | 0.703 |

| Path | Standardized Coefficients | C.R. | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | |||

| worry about comprehension | skill | −0.344 | −6.721 | <0.000 |

| worry about comprehension | attitude | −0.248 | −5.128 | <0.000 |

| lack of satisfaction in reading ability | skill | 0.298 | 5.689 | <0.000 |

| lack of satisfaction in reading ability | attitude | 0.461 | 8.091 | <0.000 |

| lack of satisfaction in reading ability | awareness | 0.516 | 9.985 | <0.000 |

| lack of satisfaction in reading ability | knowledge | 0.148 | 2.477 | 0.013 |

| language distance | skill | −0.535 | −12.664 | <0.000 |

| language distance | awareness | −0.430 | −9.596 | <0.000 |

| language distance | knowledge | −0.249 | −4.323 | <0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, H.-C.; Huang, S.-h.C. The Impact of Reading Anxiety of English Professional Materials on Intercultural Communication Competence: Taking Students Majoring in the Medical Profession. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416980

Liao H-C, Huang S-hC. The Impact of Reading Anxiety of English Professional Materials on Intercultural Communication Competence: Taking Students Majoring in the Medical Profession. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416980

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Hung-Chang, and Sheng-hui Cindy Huang. 2022. "The Impact of Reading Anxiety of English Professional Materials on Intercultural Communication Competence: Taking Students Majoring in the Medical Profession" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416980

APA StyleLiao, H.-C., & Huang, S.-h. C. (2022). The Impact of Reading Anxiety of English Professional Materials on Intercultural Communication Competence: Taking Students Majoring in the Medical Profession. Sustainability, 14(24), 16980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416980