A Systematic Review: How Does Organisational Learning Enable ESG Performance (from 2001 to 2021)?

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Consolidate the state of the research to date on the liaison between organisational learning and ESG (integration with enterprise strategy and operations).

- (2)

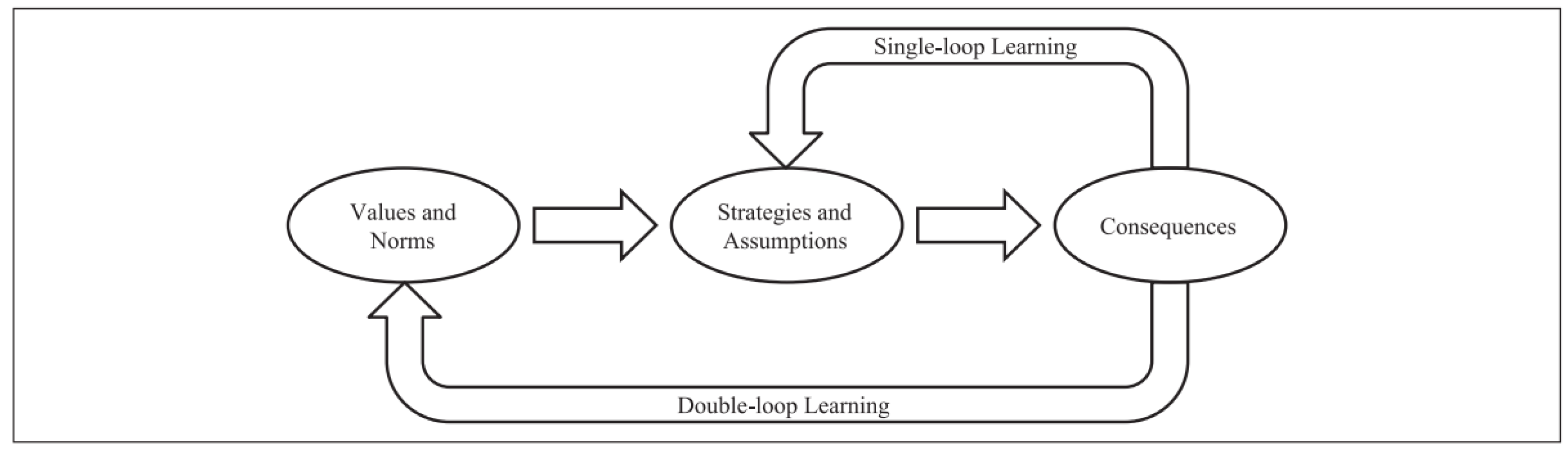

- How does organisational learning affect ESG consequences, including the questions such as how can a common consciousness (values and norms) be increased, and what are the main factors influencing the process (strategies and assumptions) of organisational learning related to ESG?

2. Literature Review

2.1. ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance)

2.1.1. The Background of ESG

2.1.2. The Theoretical Fundamentals of ESG

2.1.3. The Implementation of ESG

2.2. Organisational Learning

2.2.1. A Historical Overview of Research on Organisational Learning

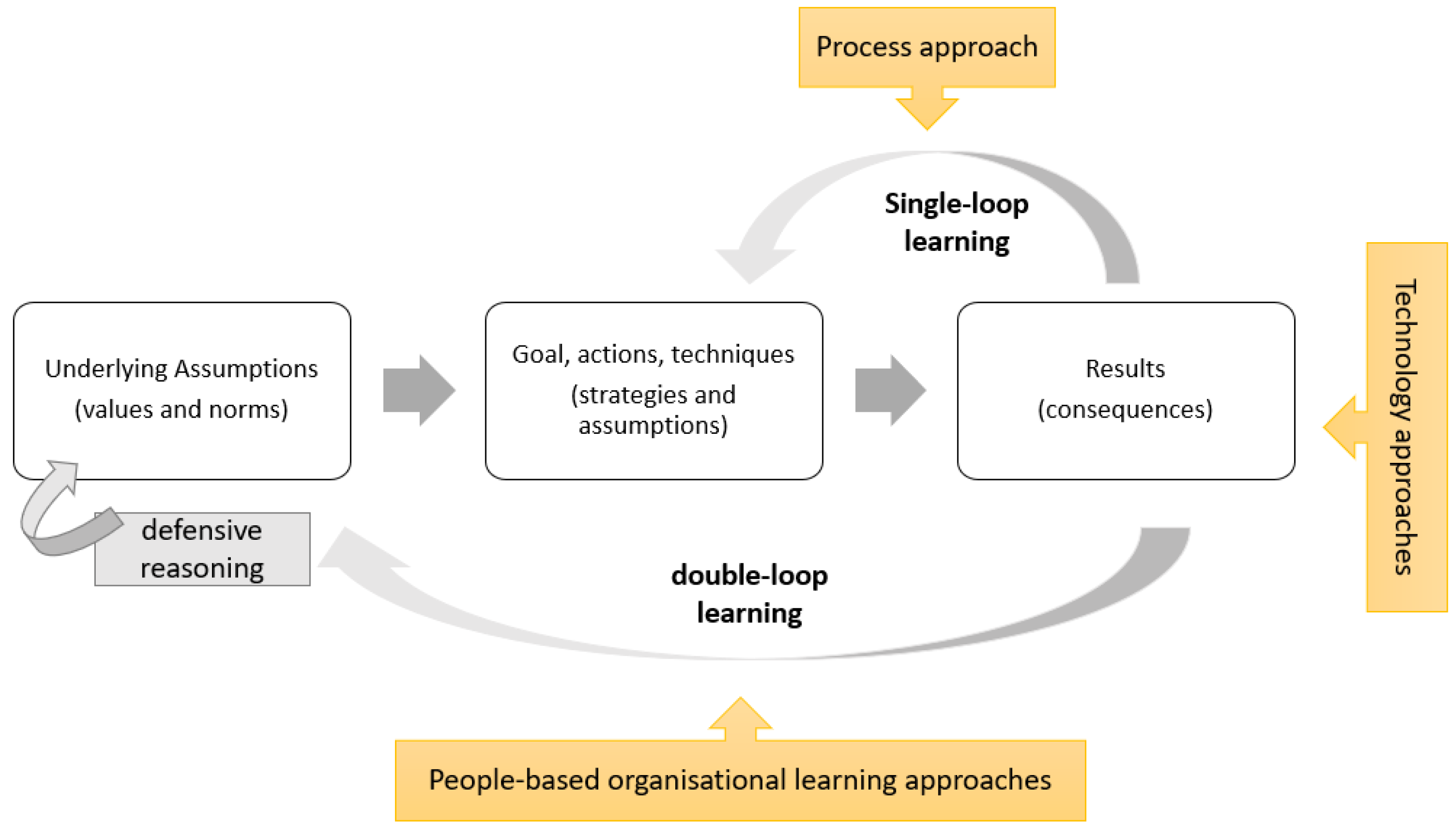

2.2.2. Single- and Double-Loop Learning

2.2.3. The Effectiveness of Organisational Learning

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Article Characteristics

4.2. Data Analysis

4.3. Synthesis

5. Discussion

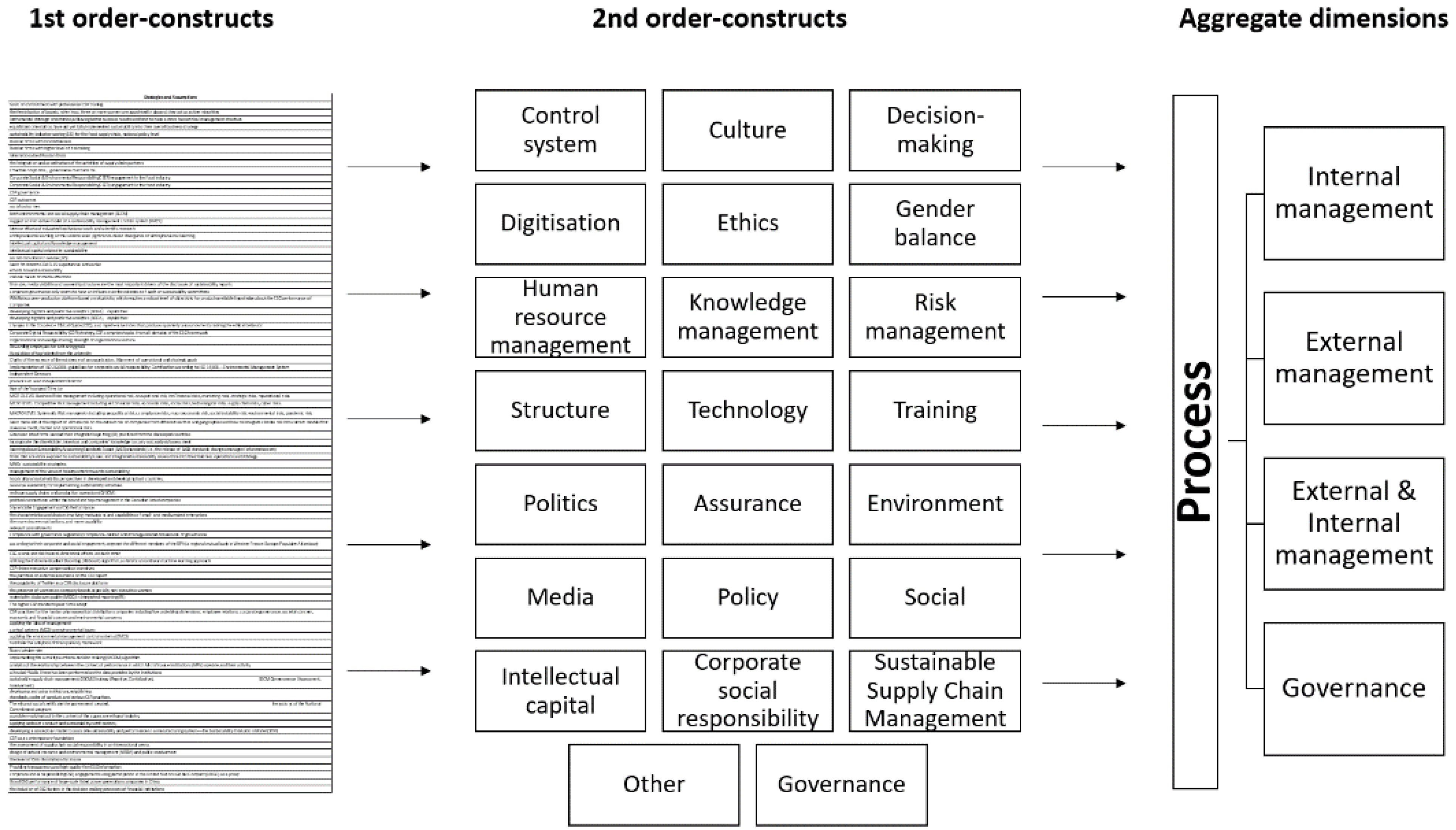

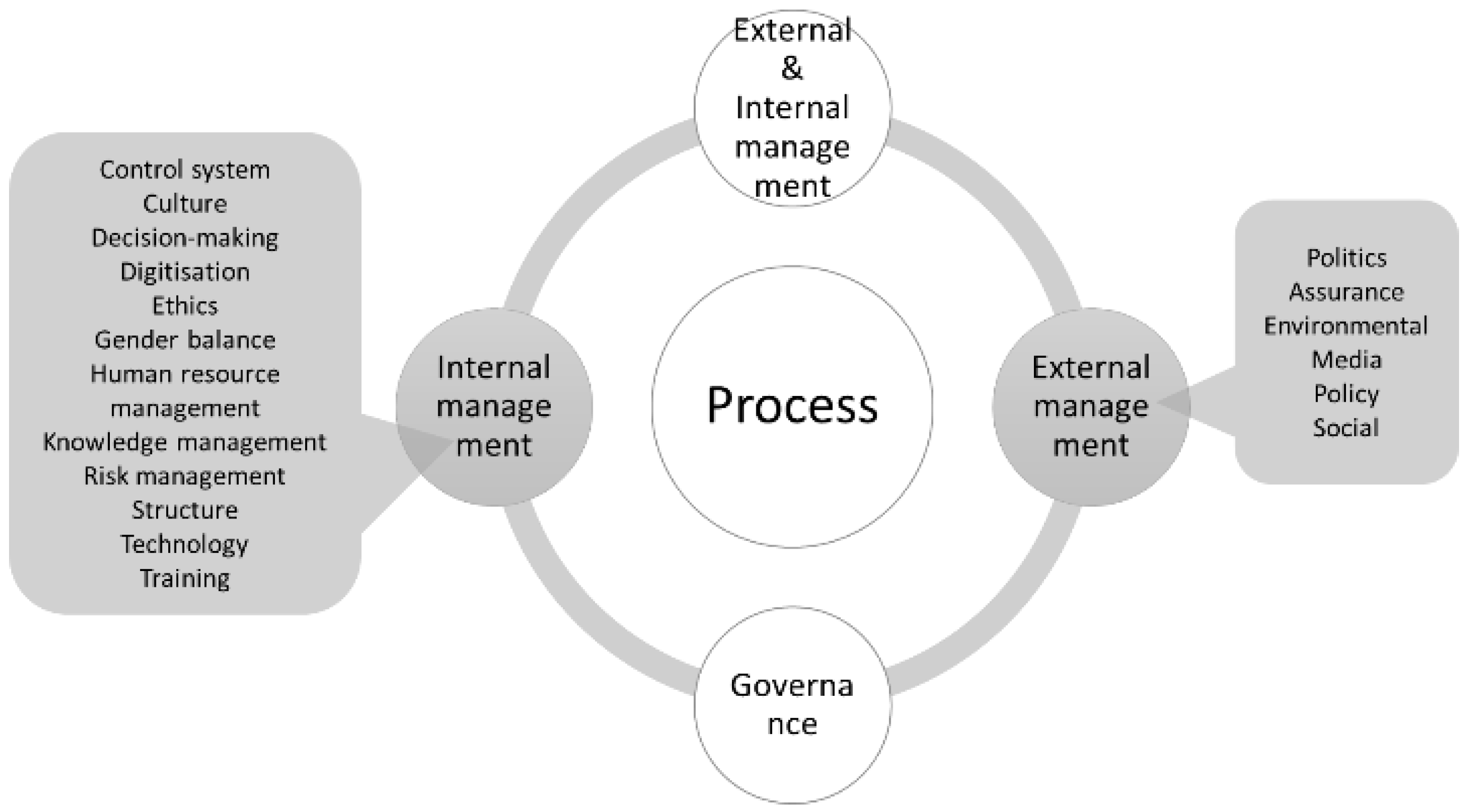

5.1. Process

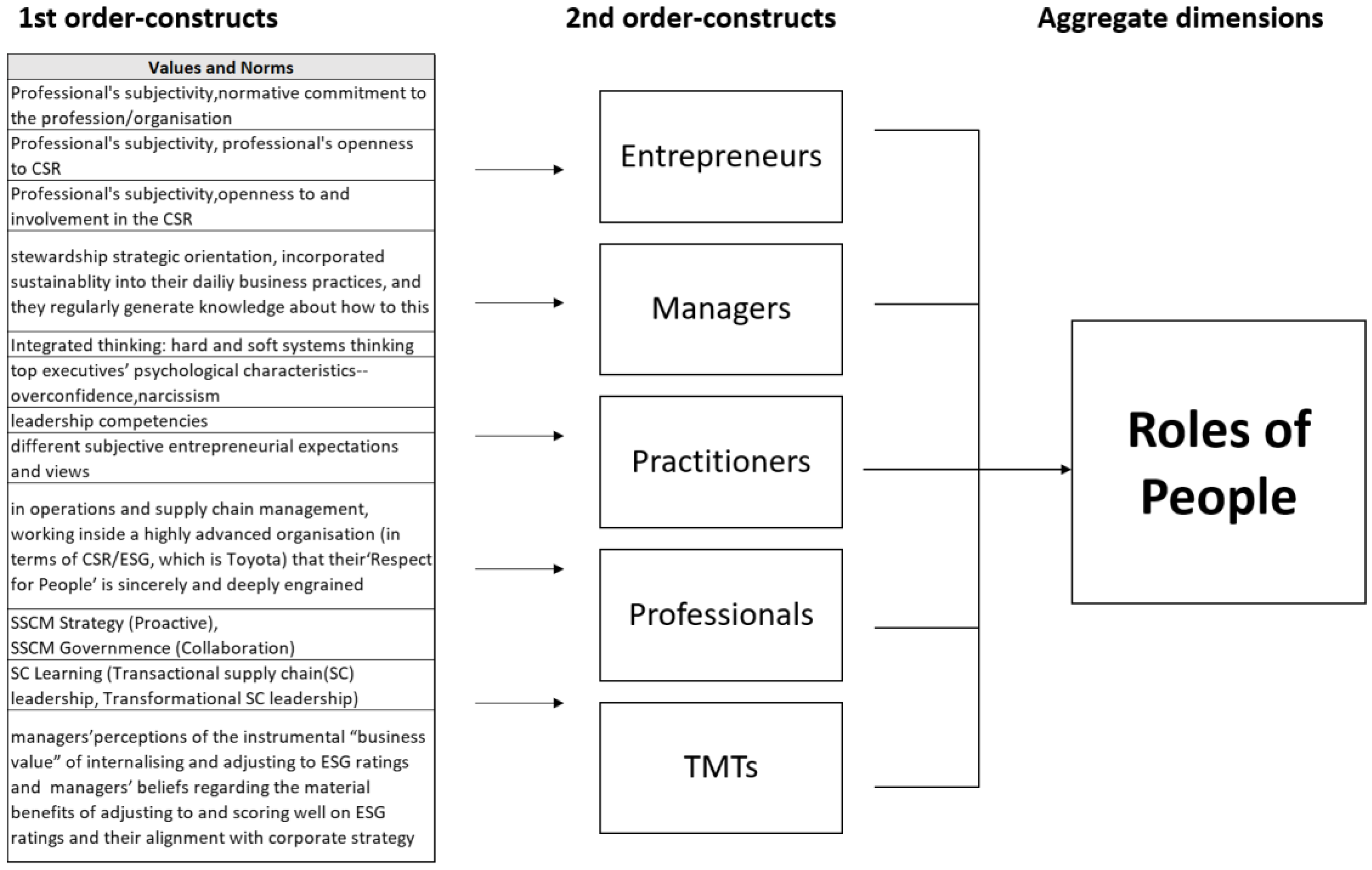

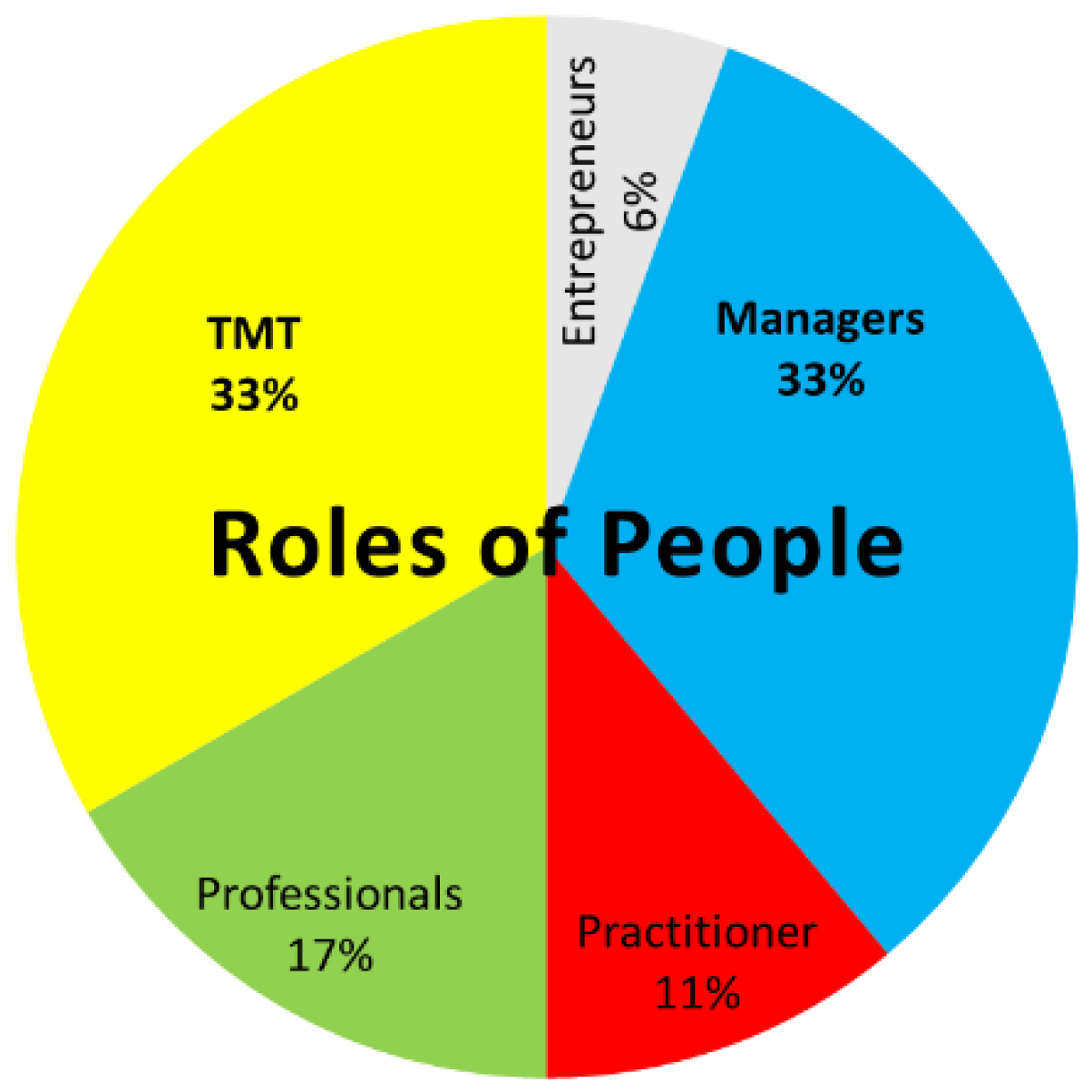

5.2. People

5.3. Strengths and Limitations

5.4. Future Research and Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

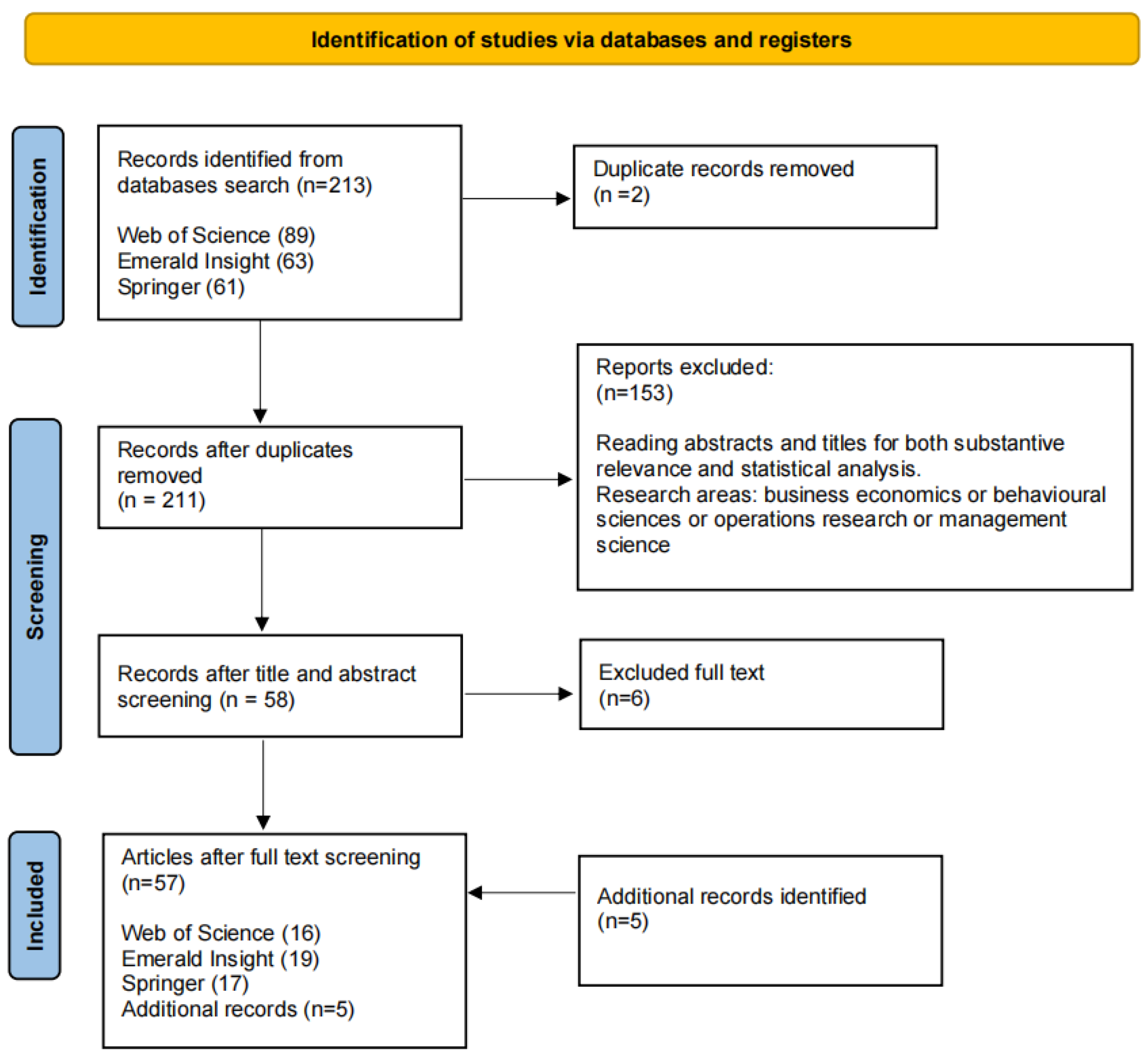

| Filter | No. | Description | Total Result | Web of Science Results | Emerald Insight Results | Springer Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substantive | 1 | All articles Tops with ‘organisational learning’ or ‘organizational learning’ | >437,839 | 41,517 | >110,000 | 286,322 |

| Substantive | 2 | All articles Tops with ESG or ‘Environmental, Social, Governance’ | >133,756 | 15,832 | >1000 | 116,924 |

| Substantive | 3 | At least one of 17 additional keywords must also appear in title or abstract or keywords (‘sustainab*’ or ‘CSR' or ‘corporate social respons*’ or ‘economic externality’ or ‘creat* knowledge’ or ‘retain*knowledge’ or ‘transfer* knowledge’ or ‘gain* knowledge’ or ‘individual learning’ or ‘team learning’ or ‘inter-organisational learning’ or ‘communities of learning’ or ‘group learning’ or ‘knowledge transfer*’ or ‘knowledge retent*’ or ‘knowledge creat*’) | >1,696,592 | 1,588,029 | >97,000 | 11,563 |

| Substantive | 4 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 | 674 | 142 | 86 | 446 |

| Methodological | 5 | At least one of seven keywords indicating empirical data or analysis must also appear in title or abstract (data or empirical or test* or statistic* or finding* or result* or evidence) | 603 | 103 | 86 | 414 |

| Substantive | 6 | And Document types: (article) And Languages: (English) And Publication Year 2001 to Year 2021 | 213 | 89 | 63 | 61 |

| Duplicates | 7 | Deletion of duplicate articles found in both databases | 211 | 88 | 63 | 60 |

| Substantive and methodological | 8 | Remaining abstracts read for both substantive relevance and statistical analysis Research areas: business economics or behavioral sciences or operations research or management science | 58 | 19 | 20 | 19 |

| Substantive and methodological | 9 | Remaining full articles read for both substantive relevance and statistical analysis | 52 | 16 | 19 | 17 |

References

- Ditlev-Simonsen, C.D. Sustainability and Finance: Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG). In A Guide to Sustainable Corporate Responsibility: From Theory to Action; Ditlev-Simonsen, C.D., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.H.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, J.H.; Wu, M.Y.; Li, D.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Kang, J.G. ESG and Corporate Financial Performance: Empirical Evidence from China's Listed Power Generation Companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayegh, M.F.; Abdul Rahman, R.; Homayoun, S. Corporate Economic, Environmental, and Social Sustainability Performance Transformation through ESG Disclosure. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, W.M.W.; Zaini, R.; Kassim, A.A.M. Women on boards, firms' competitive advantage and its effect on ESG disclosure in Malaysia. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Does it really pay to be green? Determinants and consequences of proactive environmental strategies. J. Account. Public Policy 2011, 30, 122–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafeim, G. Social-impact efforts that create real value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020, 98, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Argote, L.; Lee, S.; Park, J. Organizational Learning Processes and Outcomes: Major Findings and Future Research Directions. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 5399–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. Single-Loop and Double-Loop Models in Research on Decision Making. Adm. Sci. Q. 1976, 21, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, M. Is ESG the succeeding risk factor? J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2021, 11, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, L.; Griswold, J.S.; Jarvis, W.F. From SRI to ESG: The Changing World of Responsible Investing. Commonfund Inst. 2013, 17, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Business Roundtable Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote ‘an Economy That Serves All Americans’. 2019. Available online: https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Henisz, W.; Koller, T.; Nuttall, R. Five ways that ESG creates value. McKinsey Q. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Volz, U. Fostering green finance for sustainable development in Asia. In Routledge Handbook of Banking and Finance in Asia; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K.; Wawak, S.; Tyrańska, M.; Zakrzewska, M.; Jarosz, S.; Sołtysik, M. Research trends in human resource management. A text-mining-based literature review. Int. J. Manpow. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K.; Sołtysik, M.; Różycka-Antkowiak, J.Ł. Implementation of Management 3.0: Its consistency and conditional factors. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2022, 35, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. Three theoretical foundation suppoting ESG. Financ. Account. Mon. 2021, 8, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; World Commission on Environment and Development: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Enter The Triple Bottom Line. 2004. Available online: www.johnelkington.com.TBL-elkington-chapter.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Freeman, R.E.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B. Stakeholder theory and “the corporate objective revisited”. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel-Zadeh, A.; Serafeim, G. Why and How Investors Use ESG Information: Evidence from a Global Survey. Financ. Anal. J. 2018, 74, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolo, M.; Filipiak, B.Z.; Bak, I.; Cheba, K. How to Design More Sustainable Financial Systems: The Roles of Environmental, Social, and Governance Factors in the Decision-Making Process. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Koelbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings. Rev. Finance 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, M.; Mango, F.; Cafaro, A.; Leo, S. Does the ESG Index Affect Stock Return? Evidence from the Eurostoxx50. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. ESG in focus: The Australian evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Creating sustainable value. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senadheera, S.S.; Withana, P.A.; Dissanayake, P.D.; Sarkar, B.; Chopra, S.S.; Rhee, J.H.; Ok, Y.S. Scoring environment pillar in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) assessment. Sustain. Environ. 2021, 7, 1960097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, D. Do Corporate Social Responsibility Engagements Lead to Real Environmental, Social, and Governance Impact? Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 2564–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schon, D.A. Organizational Learning. A Theory of Action Perspective. Read. Mass 1978, 77/78, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. Overcoming Organizational Defenses: Facilitating Organizational Learning; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm; Wiley-Blackwell: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Epple, D.; Argote, L.; Murphy, K. An empirical investigation of the microstructure of knowledge acquisition and transfer through learning by doing. Oper. Res. 1996, 44, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, V.; Saadat, Z. Organizational learning as a key role of organizational success. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 230, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva, R.; Ghauri, P.; Alegre, J. Organizational learning, innovation and internationalization: A complex system model. British J. Manag. 2014, 25, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I. A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 1995; Volume 105. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Increasing Leadership Effectiveness; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schon, D.A. Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness; Jossey-bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Inner Contradictions of Rigorous Research; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Reasoning, Learning, and Action: Individual and Organizational; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Putnam, R.; Smith, D. Action Science: Concepts, Methods, and Skills for Research and Intervention; Jossey-bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Strategy, Change and Defensive Routines; Pitman Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C.; Schon, D.A. Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method, and Practice. ILR Rev. 1997, 50, 701. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I. The Knowledge-Creoting Compony. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1991, 69, 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Garvin, D.A. Building a learning organization. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Basten, D.; Haamann, T. Approaches for organizational learning: A literature review. Sage Open 2018, 8, 2158244018794224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dooren, W. Better performance management: Some single-and double-loop strategies. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2011, 34, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakacsi, G. Managing crisis: Single-loop or double-loop learning? Strateg. Manag. Int. J. Strateg. Manag. Decis. Support Syst. Strateg. Manag. 2010, 15, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Double-Loop Learning, Teaching, and Research. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2002, 1, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapuji, H.; Crossan, M. From questions to answers: Reviewing organizational learning research. Manag. Learn. 2004, 35, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkema, H.G.; Bell, J.H.; Pennings, J.M. Foreign entry, cultural barriers, and learning. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennings, J.M.; Barkema, H.; Douma, S. Organizational learning and diversification. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 608–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, M.L. When do firms learn from their acquisition experience? Evidence from 1990 to 1995. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hurley, R.F.; Giunipero, L.C.; Nichols Jr, E.L. Organizational learning in global purchasing: A model and test of internal users and corporate buyers. Decis. Sci. 2000, 31, 293–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, D. An organizational learning approach to product innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. Int. Publ. Prod. Dev. Manag. Assoc. 1992, 9, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezias, S.J.; Glynn, M.A. The three faces of corporate renewal: Institution, revolution, and evolution. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, J.R.; Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Stoddard, D.B. Business reengineering at CIGNA corporation: Experiences and lessons learned from the first five years. Mis Q. 1994, 18, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robey, D.; Sahay, S. Transforming work through information technology: A comparative case study of geographic information systems in county government. Inf. Syst. Res. 1996, 7, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, M. Organizational learning: A review of some literatures. Organ. Stud. 1993, 14, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allameh, M.; Moghaddami, M. The survey of relationship between organizational learning and organizational-performance. (Case study: Nirou moharreke unit of Iran khodro company). J. Exec. Manag. 2010, 10, 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The fifth discipline. Meas. Bus. Excell. 1997, 1, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A. Interactions between investments in innovation and SME competitiveness in the peripheral regions. J. Int. Stud. 2021, 14, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoliu, N.; Bilan, Y.; Mishchuk, H. Vocational training costs and economic benefits: Exploring the interactions. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 22, 1476–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meekaewkunchorn, N.; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, K.; Muangmee, C.; Kassakorn, N.; Khalid, B. Entrepreneurial orientation and SME performance: The mediating role of learning orientation. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 14, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S.L. Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R.J.; Han, S.K. A systematic assessment of the empirical support for transaction cost economics. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouadi, A.; Marsat, S. Do ESG Controversies Matter for Firm Value? Evidence from International Data. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, J.J.; Brown, R.R.; Farrelly, M.A. A design framework for creating social learning situations. Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2013, 23, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J.M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick, D.C. Upper echelons theory: An update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, C.; Sobczak, A. Towards a Model of Corporate and Social Stakeholder Engagement: Analyzing the Relations Between a French Mutual Bank and Its Members. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.Y.-S. Hospitality Industry Web-Based Self-Service Technology Adoption Model:A Cross-Cultural Perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 162–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.; Galletta, D.F.; King, W.R. Integrating national culture into IS research: The need for current individual level measures. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 15, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manita, R.; Bruna, M.G.; Dang, R.; Houanti, L.H. Board gender diversity and ESG disclosure: Evidence from the USA. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2018, 19, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.; Yaacob, H.; Parveen, S.; Zaini, Z. Big data and predictive analytics to optimise social and environmental performance of Islamic banks. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2021, 41, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, R.J. Social and Environmental Performance at SMEs: Considering Motivations, Capabilities, and Instrumentalism. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diduck, A.; Sinclair, A.J.; Hostetler, G.; Fitzpatrick, P. Transformative learning theory, public involvement, and natural resource and environmental management. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2012, 55, 1311–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. A Life Full of Learning. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 1178–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ge, J. Replying to management challenges: Integrating oriental and occidental wisdom by HeXie management theory. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2012, 6, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environment | Social | Governance |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon intensity emission | Business behaviour | Antitakeover policy |

| Climate change | Community relations | Audit and control system |

| Control of environmental impacts | Corporate citizenship/philanthropy | Board diversity |

| Eco-design (financial green) | Customer relationship management | Board structure |

| products and services) | Customer and product responsibility | Board management |

| Eco efficiency | Diversity | Business ethics and fraud |

| Emissions | Human capital development and training | Codes of conduct/compliance |

| Energy consumptions | Human rights criteria | Corporate government functions and |

| Environmental policy | Labor management | commitments |

| Management | Local suppliers | Prevention of corruption and bribery |

| Environmental reporting | Market ethics | Remuneration of members of executive team |

| Environmental risk management | Non-discrimination, promotion equality | Respect of shareholders rights |

| Hazardous waste | Privacy and data security | Risk and crisis management |

| Materials recycled and reused | Protection of children | Transparency |

| Packaging | Exclusion of children labor | Vision and strategy |

| Pollutions management/resources | Quality of working conditions | Antitrust policy |

| Protections of biodiversity | Respect of trade unions | Industry specific criteria |

| Raw material sourcing | Responsible investing | |

| Renewable energy consumption | Rights of indigenous people | |

| Travel and transport impact | Social reporting | |

| Waste management reduction | Stakeholder engagement | |

| Water use and management | Supply chain management | |

| Industry-specific criteria | Talent attraction/retention | |

| Work-life balance | ||

| Industry-specific criteria |

| ‘organisational learning’ or ‘organizational learning’ |

|---|

| ESG or ‘Environmental, Social, Governance’ |

| 17 additional keyword: ‘sustainab*’ or ‘CSR' or ‘corporate social respons*’ or ‘economic externality’ or ‘creat* knowledge’ or ‘retain*knowledge’ or ‘transfer* knowledge’ or ‘gain* knowledge’ or ‘individual learning’ or ‘team learning’ or ‘inter-organisational learning’ or ‘communities of learning’ or ‘group learning’ or ‘knowledge transfer*’ or ‘knowledge retent*’ or ‘knowledge creat*’ |

| Journals Publishing Organisational Learning and ESG Research | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| NO | Source Title | No. of Articles | % of Total Articles |

| 1 | Annals of Operations Research | 1 | 1.8% |

| 2 | British Food Journal | 3 | 5.3% |

| 3 | Business Strategy and the Environment | 1 | 1.8% |

| 4 | Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society | 2 | 3.5% |

| 5 | Data Technologies and Applications | 1 | 1.8% |

| 6 | Environment, Development and Sustainability | 1 | 1.8% |

| 7 | Environment Systems and Decisions | 1 | 1.8% |

| 8 | Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management | 1 | 1.8% |

| 9 | Journal of Organizational Change Management | 1 | 1.8% |

| 10 | Journal of Applied Accounting Research | 1 | 1.8% |

| 11 | Journal of Business Ethics | 8 | 14.0% |

| 12 | Journal of Cleaner Production | 7 | 12.3% |

| 13 | Journal of Environmental Planning and Management | 1 | 1.8% |

| 14 | Journal of Management and Governance | 2 | 3.5% |

| 15 | Journal of Intellectual Capital | 1 | 1.8% |

| 16 | Journal of Service Management | 1 | 1.8% |

| 17 | Journal of Strategy and Management | 1 | 1.8% |

| 18 | Intereconomics | 1 | 1.8% |

| 19 | International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing | 1 | 1.8% |

| 20 | International Journal of Accounting Information Systems | 1 | 1.8% |

| 21 | International Journal of Disclosure and Governance | 1 | 1.8% |

| 22 | International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research | 1 | 1.8% |

| 23 | International Journal of Operations & Production Management | 1 | 1.8% |

| 24 | International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management | 1 | 1.8% |

| 25 | Management Decision | 1 | 1.8% |

| 26 | Managerial Auditing Journal | 1 | 1.8% |

| 27 | Management Science | 1 | 1.8% |

| 28 | Operations Management Research | 1 | 1.8% |

| 29 | Review of Managerial Science | 1 | 1.8% |

| 30 | Society and Business Review | 1 | 1.8% |

| 31 | Supply Chain Management-An International Journal | 2 | 3.5% |

| 32 | Sustainability | 5 | 8.8% |

| 33 | Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal | 2 | 3.5% |

| 34 | Sustainability Management Forum | NachhaltigkeitsManagementForum | 1 | 1.8% |

| 1st Order-Constructs of Single-Loop Learning | |

|---|---|

| Process | Strategies and Assumptions |

| Internal management: decision-making (19) | Russian firms with innovativeness |

| Russian firms with higher level of risk-taking | |

| internationalized Russian firms | |

| the integration and coordination of the activities of supply chain partners | |

| Clarity of the essence of the existence of an organization; Alignment of operational and strategic goals | |

| firms that are more exposed to sustainability issues and integrated sustainability issues more into their business operations and strategy. | |

| MNEs' sustainability strategies; | |

| resource availability for implementing sustainability initiatives. | |

| reshape supply chains and production operations(O/SCM) | |

| the characteristics and choices involving motivations and capabilities of small- and mediumsized enterprises | |

| the more sincere motivations, and more capability relevant commitments | |

| The higher CSP standards peer firms adopt | |

| CSR practices for the Iranian pharmaceutical distribution companies including five underlying dimensions: employee relations, corporate governance, societal concern, economic and financial concern and environmental concerns. | |

| facilitate the adoption of transparency framework | |

| implementing the a multiple criteria decision making (MCDM) algorithm | |

| developing a conceptual model to associate sustainability and performance in a manufacturing system—the Sustainability Evaluation Model (SEM) | |

| design of natural resource and environmental management (NREM) and public involvement | |

| corporate social responsibility(CSR) engagements using participation in the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) as a proxy | |

| the inclusion of ESG factors in the decision-making processes of financial institutions | |

| Internal management: knowledge management (14) | WikiRate, a peer-production platform based on situativity, which requires a robust level of objectivity for producing reliable knowledge about the ESG performance of companies. |

| developing big data and predictive analytics (BDPA) capabilities | |

| developing big data and predictive analytics (BDPA) capabilities | |

| Organizational knowledge sharing | |

| Certification according to ISO 14,001—Environmental Management System | |

| learn more about the impact of climate risk on the default risk of companies from different sectors and geographies and how to integrate climate risk into current models that measure credit, market and operational risks. | |

| Ghanaian listed firms learned their integrated reporting (IR) practices from the developed countries. | |

| incorporate the shareholder, investors and companies’ knowledge to carry out analysis/assessment | |

| utilizing the Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm, a statistical nonlinear machine learning approach | |

| analysis of the relationship between the context of performance in which Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) operate and their activity | |

| a Kruskal-Wallis H test has been performed on the data provided by the Institutions | |

| developing and using institutions, establishing standards, codes of conduct, and various CSR practices. | |

| the level of ESG information disclosure | |

| Providing transparency and high-quality firm ESG information | |

| Internal management: training (6) | form of commitment with professional CSR traning |

| intense efforts of educated institutional work and scientific research | |

| entrepreneurial learning at the societal level /ignorance-based divergence of entrepreneurial learning | |

| Implementation of ISO 26,000—guidelines for corporate social responsibility; | |

| learn from both COVID-19 experiences and earlier efforts toward sustainability | |

| learning about Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) standards (i.e., the release of SASB standards changes managers’ information set) | |

| Internal management: risk management (3) | MICRO LEVEL Business Risks management including operational risk, occupational risk, Int. Financial risks, marketing risks, strategic risks, reputational risks. |

| MESO LEVEL Competitive Risk management including ext. financial risks, economic risks, social risks, technological risks, supply chain risks, cyber risks. | |

| MACRO LEVEL Systematic Risk management including geopolitical risks, compliance risks, macroeconomic risk, social instability risk, environmental risks, pandemic risks | |

| Internal management: culture (3) | Strength of organizational culture |

| management of the views of headquarters towards sustainability; | |

| local cultural sustainability perspectives in developed and developing host countries; | |

| Internal management: stucture (2) | instrumental strategic orientation, achieving better business results and tend to have a more hierarchical management structure. |

| equidistant orientation, have not yet fully implemented sustainability into their overall business strategy | |

| Internal management: gender balance (2) | the feminization of boards, when two, three or more women are appointed in aboard, they act as active minorities, |

| the presence of women on company boards, especially non-executive women | |

| Internal management: human resource (2) | Rewarding employees for achieving goals; Acquisition of top talents from the university |

| CSR-linked executive compensation incentives | |

| Internal management: ethics (2) | changes in the Covalence Ethical Quote (CEQ), a comprehensive index that produces quarterly announcements ranking the ethical behavior |

| applying codes of conduct and sustainability certifications, | |

| Internal management: digitisation (1) | Corporate Digital Responsibility (CDR) strategy, CDR comprises topics from all domains of the ESG framework |

| Internal management: technology (1) | a problem-solving tool in the context of the sugarcane ethanol industry |

| Internal management: control system (1) | suggest an innovative model of a sustainability management control system (SMCS) |

| External management: policy (5) | sustainability indicator scoring (SIS) for the food supply chain, national policy level |

| compliance with governance regulation/compliance-related and strategy-related dimensions of governance | |

| ESG scores and risk have bi-directional effects on each other | |

| materiality disclosure quality (MDQ) in integrated reporting (IR) | |

| The ethanol social certificate the government created, the actions of the National Commitment program | |

| External management: environmental (2) | applying the idea of management and control systems (MCS) to environmental issues |

| applying the environmental management control systems (EMCS) | |

| External management: media (2) | various facets of media attention |

| the popularity of Twitter as a CSR disclosure platform | |

| External management: politics (1) | political connections within the board and top management in the Canadian listed companies |

| External management: social (1) | according to their corporate and social engagement, segment the different members of the BPA (a regional mutual bank in Western France: Banque Populaire Atlantique) |

| External management: assurance (1) | the purchase of external assurance on the CSR report |

| External & Internal management: SSCM (3) | both environmental and social supply chain management (SSCM) |

| the assessment of supply chain social responsibility in an international arena. | |

| sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) Strategy (Reavtive, Contirbutive); SSCM Governmence (Assessment, Involvement) | |

| External & Internal management: Other (3) | social innovation in service (SIS) |

| firm size, media visibility and ownership structure are the most important drivers of the disclosure of sustainability reports | |

| Good ESG performance of large-scale listed power generation companies in China | |

| External & Internal management: Intellectual capital (2) | intellectual capital and knowledge management |

| intellectual capital related to sustainability | |

| External & Internal management: CSR (1) | CSR as a contemporary foundation |

| governmance (12) | Effective corporate and governance mechanisms |

| Corporate Social & Environmental Responsibility (CSER) engagement in the food industry. | |

| Corporate Social & Environmental Responsibility (CSER) engagement in the food industry. | |

| CSR governance | |

| CSR outcomes | |

| social outcomes | |

| corporate governance only seems to have an influence on the existence of audit or sustainability committees | |

| Independent Directors | |

| presence of Lead Independent Director | |

| Age of the Youngest Director | |

| Shareholder Engagement on ESG Performance | |

| Board pledge rate | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, J. A Systematic Review: How Does Organisational Learning Enable ESG Performance (from 2001 to 2021)? Sustainability 2022, 14, 16962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416962

Xia J. A Systematic Review: How Does Organisational Learning Enable ESG Performance (from 2001 to 2021)? Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416962

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Jingwen. 2022. "A Systematic Review: How Does Organisational Learning Enable ESG Performance (from 2001 to 2021)?" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416962

APA StyleXia, J. (2022). A Systematic Review: How Does Organisational Learning Enable ESG Performance (from 2001 to 2021)? Sustainability, 14(24), 16962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416962