PROSPER (Project, Sustainability, and Perseverance) Learning Model in English for Computer Science

Abstract

1. Introduction

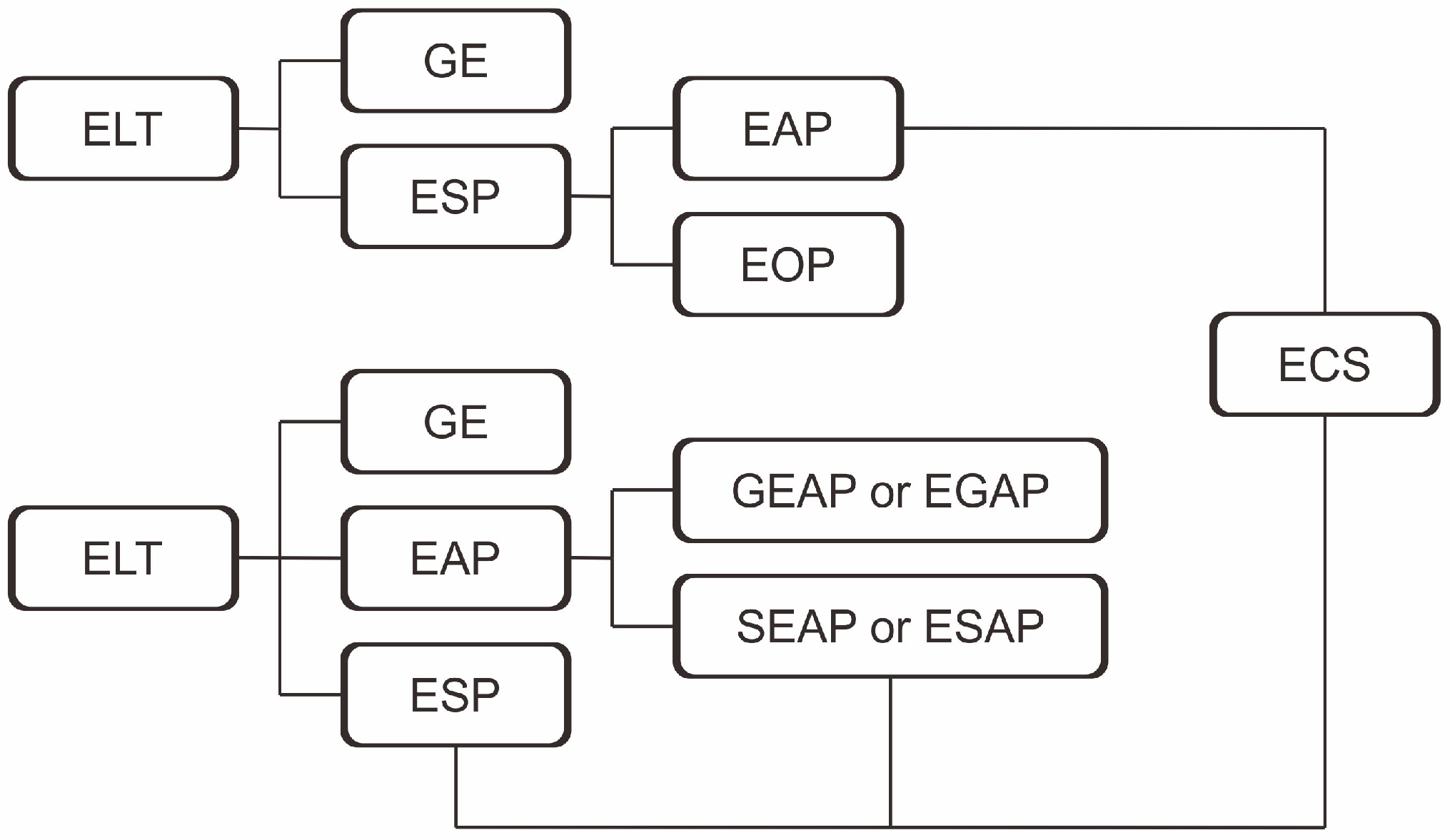

2. English for Computer Science

3. PROSPER (Project, Sustainability, and Perseverance)

3.1. Specification

- The syntax of the PROSPER learning model was developed from the research of Alan and Stoller [49], Fragoulis [50], Thitivesa [51], and Akharraz [52]:

- (a)

- Choosing the theme of the project.

- (b)

- Open-class discussion on correlations of the theme and sustainability.

- (c)

- Meeting the experts.

- (d)

- Structuring the project by considering its contribution to sustainability.

- (e)

- Executing the project in a sustainable way.

- (f)

- Presenting the project.

- (g)

- Evaluating the project.

- (h)

- Publishing the project.

- The supporting systems in this learning model are the:

- (a)

- Lesson Plan.

- (b)

- Project Instruction.

- (c)

- Supplementary Learning Materials.

- (d)

- Learning Evaluation Instruments.

This supporting system is designed to assist lecturers and students in using the PROSPER learning model. - The social system created in this learning model is more geared towards collaboration in finishing the project. Students work in small groups, and it is also possible for them to search for advice from experts, their classmates (even if they are not in the same group), the lecturers, and society, locally and globally. The lecturer’s role is mostly as a facilitator.

- The reaction principle defines how the lecturers facilitate the learning process by:

- (a)

- Supporting students to work collaboratively.

- (b)

- Connecting students with experts.

- (c)

- Facilitating students to look for a solution when they become stuck with their project.

- (d)

- Freeing students to choose their own way of contributing as agents of change.

- The expected instructional impacts from the PROSPER learning model are:

- (a)

- Basic twenty-first century skills; critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, and communication (4C).

- (b)

- Awareness and involvement in sustainability based on their field.

- (c)

- Perseverance and continuing despite being beset by obstacles.

- (d)

- Having students as agents of change to contribute to the improvement of the world’s living conditions.

- The expected side effect is to increase interest in learning and working collaboratively rather than competitively.

3.2. Principles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bekteshi, E.; Xhaferi, B. Learning about sustainable development goals through English language teaching. Res. Soc. Sci. Technol. 2020, 5, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Sahan, E.; Wills, T.; Croft, S. Creating the New Economy: Business Models That Put People and Planet First. 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338955457 (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Kawano, E. Solidarity economy: Building an economy for people and planet. In The New Systems Reader; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 285–302. [Google Scholar]

- Roobeek, A.; De Swart, J.; Van Der Plas, M. Responsible Business: Making Strategic Decisions to Benefit People, the Planet and Profits; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aragon-Correa, J.A.; Marcus, A.A.; Rivera, J.E.; Kenworthy, A.L. Sustainability management teaching resources and the challenge of balancing planet, people, and profits. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtenberg, J. Building a Culture for Sustainability: People, Planet, and Profits in a New Green Economy; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, F.; Post, J.E. Business models for people, planet (& profits): Exploring the phenomena of social business, a market-based approach to social value creation. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 715–737. [Google Scholar]

- Burritt, R.L. Environmental performance accountability: Planet, people, profits. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2012, 25, 370–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagoma, Y.; Stall, N.; Rubinstein, E.; Naudie, D. People, planet and profits: The case for greening operating rooms. CMAJ 2012, 184, 1905–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowden, R. Teaching English for sustainability. J. NELTA 2010, 15, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, R.; Kawai, A.; Morihiro, K.; Isu, N. A feedback-augmented method for detecting errors in the writing of learners of English. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Computational Linguistics and 44th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Sydney, Australia, 17–18 July 2006; pp. 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M. English for Specific Purposes (ESP): A Holistic Review. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 3, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley-Evans, T.; St John, M.J.; Saint John, M.J. Developments in English for Specific Purposes: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, L. English for Specific Purposes: What does it mean? Why is it different. On-CUE J. 1997, 5, 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley-Evans, T. Five questions for LSP teacher training. In Teacher Education for Languages for Specific Purposes; Howard, R., Brown, G., Eds.; Multilingual Matters Ltd.: Clevedon, New Zealand, 1997; pp. 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Belcher, D. (Ed.) What ESP is and can be: An introduction. In English for Specific Purposes in Theory and Practice; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2009; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, M.J.; Frieze, D. Walk out Walk on: A Learning Journey into Communities Daring to Live the Future Now; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Fransisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Peterson, C.; Matthews, M.D.; Kelly, D.R. Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankay, A. The impact of growth mindset on perseverance in writing. J. Teach. Action Res. 2020, 7, 60–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, K.K.L.; Zhou, M. A serial mediation model testing growth mindset, life satisfaction, and perceived distress as predictors of perseverance of effort. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 167, 110262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Chen, X.; Cheung, H.Y.; Peng, K. Teachers’ growth mindset and work engagement in the Chinese educational context: Well-being and perseverance of effort as mediators. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Septiana, I.; Petrus, I.; Inderawati, R. Needs analysis-based English syllabus for computer science students of Bina Darma University. Engl. Rev. J. Engl. Educ. 2020, 8, 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplier, C. From Scientific English to English for Science: Determining the Perspectives and Crossing the Limits. Arab. World Engl. J. (AWEJ) 2016, 7, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belinda, H. English communication needs of computer science internship and workplace. Int. J. Lang. Linguist. 2015, 2, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Puspitasari, I. English For Computer Science: Sebuah Analisis Kebutuhan Bahasa Inggris Pada Mahasiswa Teknik Informatika. Probisnis 2013, 6, 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Benchenane, D. Implementing an ESP Course to Computer Sciences Students: Case Study of Master’s Students at the University of Mustapha Stambouli Mascara. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Tlemcen-Abou Bekr Belkaid, Tlemcen, Algeria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Irshad, I.; Anwar, B. English for Specific Purposes: Designing an EAP Course for Computer Science Students. J. Educ. Educ. Dev. 2018, 5, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yürekli, A. EAP in Engineering and Computer Sciences I; Izmir University of Economics: İzmir, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.C.; Tweedie, M.G. “IELTS-out/TOEFL-out”: Is the End of general English for academic purposes near? Tertiary student achievement across standardized tests and general EAP. Interchange 2021, 52, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilcik, H.H.; Daloglu, A. Implementing an interactive reflection model in EAP: Optimizing student and teacher learning through action research. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. (Online) 2018, 43, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monbec, L. Designing an EAP curriculum for transfer: A focus on knowledge. J. Acad. Lang. Learn. 2018, 12, A88–A101. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, X. Probe into the Differences between EAP, ESP and EOP Teaching in College English Teaching. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Education, E-Learning and Management Technology, Xi’an, China, 27–28 August 2016; pp. 543–547. [Google Scholar]

- Klimova, B.F. Designing an EAP course. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 191, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kucherenko, S.; Shcherbakova, I.; Varlamova, J. A project-based ESAP course: Key features, benefits and challenges. J. Teach. Engl. Specif. Acad. Purp. 2015, 2, 671–677. [Google Scholar]

- Kucherenko, S. An integrated view of EOP and EAP. J. Teach. Engl. Specif. Acad. Purp. 2013, 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, S.; Morrison, B. The first term at university: Implications for EAP. ELT J. 2011, 65, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floris, F.D. Developing English for general academic purposes (EGAP) course in an Indonesian university. K@ta 2008, 10, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atai, M.R. EAP teacher education: Searching for an effective model integrating content and language teachers’ schemes. In Proceedings of the PAAL Conference, Kangwong National University, Chuncheon, Republic of Korea, 28–30 July 2006; pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Carkin, S. English for academic purposes. In Handbook of Research in Second Language Teaching and Learning; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Melles, G.; Millar, G.; Morton, J.; Fegan, S. Credit-based discipline specific English for academic purposes programmes in higher education: Revitalizing the profession. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 2005, 4, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, D. Some propositions about ESP. ESP J. 1983, 2, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, T.; Waters, A. English for Specific Purposes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyuni, D.S.; Darmansyah, D. Writing skills deficiency in English for specific purposes (ESP): English for computer science. J. Appl. Stud. Lang. 2021, 5, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.C.; Mullen, N.D. English for Computer Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bloor, M. Academic writing in computer science: A comparison of genres. Pragmatic Beyond New Ser. 1996, xiv, 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Meddour, M. Integrating Web-Based Teaching in ESP: A Case Study of Computer Science Students at Biskra University. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Mohamed Khider-Biskra, Biskra, Algeria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhramovna, M.N. Types of ESP in Curriculum Design. Probl. Pedagog. 2021, 5, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ruslanovna, D.Z. Teaching English for specific purposes (ESP). Int. Sci. Rev. 2017, 2, 91–92. [Google Scholar]

- Alan, B.; Stoller, F.L. Maximizing the benefits of project work in foreign language classrooms. Engl. Teach. Forum 2005, 43, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fragoulis, I.; Tsiplakides, I. Project-Based Learning in the Teaching of English as A Foreign Language in Greek Primary Schools: From Theory to Practice. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2009, 2, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Thitivesa, D. The academic achievement of writing via project-based learning. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Eng. 2014, 8, 2994–2997. [Google Scholar]

- Akharraz, M. The Impact of Project-Based Learning on Students’ Cultural Awareness. Int. J. Lang. Lit. Stud. 2021, 3, 54–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Merrill, M.; Sammalisto, K.; Ceulemans, K.; Lozano, F. Connecting competences and pedagogical approaches for sustainable development in higher education: A literature review and framework proposal. Sustainability 2021, 9, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, C. Sustainable Development, Explained! 2021. Available online: https://helpfulprofessor.com/education-for-sustainable-development (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Đorđević, J.P.; Blagojević, S.N. Project-based learning in computer-assisted language learning: An example from Legal English. Nasleđe Kragujev. 2017, 14, 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Eyraud, K.E. Dwelling Pedagogically: A Place-Based Ecopedagogy in an English-For-Academic-Purposes Intensive English Program. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goulah, J.; Katunich, J. TESOL and Sustainability: English Language Teaching in the Anthropocene Era; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goulah, J. Climate change and TESOL: Language, literacies, and the creation of eco-ethical consciousness. Tesol Q. 2017, 51, 90–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulah, J. Environmental displacement, English learners, identity and value creation Considering Daisaku Ikeda in the east-west ecology of education. In Transformative Eco-Education for Human and Planetary Survival; Oxford, R.L., Lin, J., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2012; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

| Principles | Description |

|---|---|

| System Thinking | Research into a wide range of complex systems, from the smallest to the largest size. |

| Understanding, testing, and articulation of a system’s structure, behavior, and critical components. | |

| Paying attention to systemic elements, including feedback, inertia, stocks and flows, and cascading effects. | |

| A better understanding of complex systems phenomena, including systemic inertia, path dependency, and intentionality. | |

| Connectivity and cause-and-effect linkages can be better understood. | |

| The use of modeling (qualitative or quantitative). | |

| Critical Thinking | The ability to question established norms and behaviors. |

| Personal self-reflection on one’s own ideals, perceptions, and actions. | |

| Perspectives from the outside world. | |

| Envisioning for the Future | Visualization, analysis, and appraisal of future possibilities, including multi-generational scenarios. |

| Use of a preemptive principle. | |

| Predicting what people will do next. | |

| Adapting to uncertainty and change. | |

| Personal Involvement | Involvement in the development of sustainable projects. |

| Ability and willingness to act. | |

| Willingness to learn and develop new ideas. | |

| Self-motivation. | |

| The beginning of one’s own education. | |

| Interpersonal Relations and Collaboration | Collaboration and participation as a method of problem-solving or research. |

| Confidence in dealing with conflict. | |

| Observing the world through the eyes of others. | |

| Involvement in the affairs of the community. | |

| Tolerance for Ambiguity and Certainty | Managing disputes, opposing aims and interests, contradictions, and setbacks is an essential part of leadership. |

| Constant effort or duration between beginning and concluding an activity are both examples of persistence. | |

| How to use one’s strengths when one is not sure which path to go down so that one can accept responsibility, take initiative, and endure. | |

| Communication and Use of Media | Effective intercultural communication skills. |

| Use of appropriate information and communication technology. | |

| Evaluation of media with an open mind. | |

| Strategic Action | Design and implementation of interventions, transitions, and transformations for long-term success. |

| Engaging in sustainable activities in a responsible manner. | |

| Ideas and strategies are developed and implemented. | |

| Managing projects from start to finish. | |

| Being able to recognize and deal with potential dangers. | |

| Management and control of initiatives, interventions, and transitions. | |

| Defining the areas in which people can be involved in the creative process. | |

| Taking the lead in energizing others. |

| Alan and Stoller [49] | Fragoulis and Tsiplakides [50] | Thitivesa [51] | Akharraz [52] | PROSPER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeing on a theme | Speculation | Choosing a topic | Choosing the project theme | Choosing the theme of the project |

| Determining final outcome of the project | Designing the project activities | Negotiation | Determining the project outcomes | Open-class discussion on correlation of the topic and sustainability |

| Structuring the project | Conducting the project activities | Project Determination | Structuring the project | Meeting the experts |

| Preparing students for the demands of information gathering | Evaluation | Preparing the students for the project demands | Information gathering cycles | Structuring the project by considering its contribution to sustainability |

| Gathering information | - | Gathering information | Information compilation and analysis cycle | Executing the project in a sustainable way |

| Preparing students to compile and analyze data | - | Sorting out information | Information reporting cycle | Presenting the project |

| Compiling and analyzing information | - | Submitting the project | Evaluating the project | Evaluating the project |

| Preparing students for the language demands of the final activity | - | Reflection | - | Publishing the project |

| Presenting the final project | - | - | - | - |

| Evaluating the project | - | - | - | - |

| PROSPER Learning Model Syntax | Description |

|---|---|

| Choosing the theme of the project | Students are grouped. |

| Lecturer provides themes. | |

| Students and lecturer agree on the project themes. | |

| Students choose a topic. | |

| Lecturer introduces the project goals. | |

| Students decide the project goals in group. | |

| Students decide on the audiences. | |

| Open-class discussion on correlation of the topic and sustainability | Teacher provides language intervention. |

| Students have a class discussion on the group’s topic. | |

| Students may use any media to help them in using English during the discussion. | |

| Students correlate their topics with sustainability. | |

| Students engage in a broader debate and draw connections between the project and sustainability. | |

| Teacher provides feedback on language usage, project, and sustainability. | |

| Meeting the experts | Teacher connects students with the expert. |

| The experts present their knowledge in project theme and sustainability. | |

| Students have a question and answer session with the experts. | |

| Structuring the project by considering its contribution to sustainability | Students and the teacher determine the details of the project’s contribution to sustainability. |

| Students consider their roles and responsibilities as individuals, group members, and part of society. | |

| Students design their collaborative work in groups, between groups, and beyond the classroom. | |

| Students negotiate on the time limit for completing the project. | |

| Students agree on a timeline for obtaining, sharing, and compiling data. | |

| Executing the project in a sustainable way | Lecturer provides students with a language intervention session and sustainability issues. |

| Students conduct the designed activities from the preceding step. | |

| Students gather information on their topic and pay attention to sustainable action. | |

| Students have interval information and feedback. | |

| Students discuss complications in personal relationships and the possibility of changing members in their groups. | |

| Students analyze the gathered information. | |

| Students conduct the project based on the gathered information in a sustainable way. | |

| The project should contribute to sustainability. | |

| Presenting the project | Lecturer provides students with language intervention for presentation. |

| Students may use any media to help them communicate their messages in the presentation. | |

| Groups present their projects. | |

| Teacher and other groups give feedback. | |

| Evaluating the project | Students review teachers’ and other groups’ feedback. |

| Students reflect on the language, project, and sustainability issues in their group, between groups, and with the classroom. | |

| Students may find other people beyond the classroom with skills that resonate with the project. | |

| Students are to give references for improving prospective projects. | |

| Publishing the Project | Students revise the end-product of the project. |

| Teacher reviews the language points and the value of the project. | |

| Students publish the project. It can be formal or informal depending on a class consensus. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wahyuni, D.S.; Rozimela, Y.; Ardi, H.; Mukhaiyar, M.; Darmansyah, D. PROSPER (Project, Sustainability, and Perseverance) Learning Model in English for Computer Science. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416749

Wahyuni DS, Rozimela Y, Ardi H, Mukhaiyar M, Darmansyah D. PROSPER (Project, Sustainability, and Perseverance) Learning Model in English for Computer Science. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416749

Chicago/Turabian StyleWahyuni, Dewi Sari, Yenni Rozimela, Havid Ardi, Mukhaiyar Mukhaiyar, and Darmansyah Darmansyah. 2022. "PROSPER (Project, Sustainability, and Perseverance) Learning Model in English for Computer Science" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416749

APA StyleWahyuni, D. S., Rozimela, Y., Ardi, H., Mukhaiyar, M., & Darmansyah, D. (2022). PROSPER (Project, Sustainability, and Perseverance) Learning Model in English for Computer Science. Sustainability, 14(24), 16749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416749